Annotations for Nehemiah

1:1 Nehemiah. Cupbearer (see note on v. 11) to Artaxerxes I of Persia, who reigned from 465–424 BC. In 460 a revolt broke out in Egypt that took five years to put down. A satrap north of Mesopotamia named Megabyzus also rebelled in 488 BC. Because of the turbulence of the times, the Persians may have been willing to ally themselves with minority groups such as the Jews, which may explain the high position held by Nehemiah.

1:3 The wall of Jerusalem is broken down. The wall of Jerusalem that had been destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar, despite abortive attempts to rebuild them, remained in ruins for almost a century and a half. Such a lamentable situation obviously made Jerusalem vulnerable to numerous enemies. Yet, from a mixture of apathy and fear, the Jews failed to rectify this glaring deficiency. The narrative is describing a recent failed attempt to rebuild the wall (see note on Ezr 4:23), not the original destruction of the city and its wall over a century prior.

1:4 God of heaven. See note on Ezr 1:2. The title of Ahura Mazda, the god of Zoroastrianism, the religion of Persia. Nehemiah, however, does not mind attributing this title to Yahweh. (See the article “Zoroastrianism.”

1:11 cupbearer. An important official with ready access to the king. Since he also came in contact with the harem, he was often a eunuch, but there is no evidence that this was the case with Nehemiah. The cupbearer was the chief financial officer and bearer of the signet ring (see notes on Est 3:10, 11) and in later sources is said to be the wine taster, whose job it was to sample royal beverages to test for poison.

2:1 Artaxerxes. See note on Ezr 4:7. sad in his presence. Given the self-indulgence of the Persian monarchs, it seems in character that they would prohibit their subjects from imposing grief on them. Herodotus writes of people with complaints gathering outside the king’s gate and wailing without bringing their trouble within the palace. In one instance, the wife of a condemned noble stood outside the palace gate, weeping until Darius relented and agreed to spare her husband. In this situation Nehemiah expresses fear when the Persian king notes that Nehemiah has come before him with a sad look on his face (see v. 2 and note).

2:2 I was very much afraid. Possibly, Nehemiah expected to be punished for bringing his sorrow before the king (cf. Est 4:2) In Persian reliefs, courtiers cover their faces in the king’s presence, possibly as a sign of deference. The facial expressions would be somewhat masked; however, it would be expected that the joy of working in the king’s service would be shown on every face.

2:5 where my ancestors are buried. Family ties were extremely important in the ancient Near East. One of the primary family responsibilities was to care for the remains or tombs of one’s ancestors. Artaxerxes would have been sympathetic to this appeal of Nehemiah to rebuild the city where his ancestors were buried lest it become a ruin and a wasteland. See notes on Ge 23:4; 25:8.

2:7 letters . . . provide me safe-conduct. Due to the unrest of the times, Nehemiah might have been worried about encountering hostility. He may have also expected political opposition due to the nature of his undertaking. The primary function of such letters is to instruct regional officials to supply provisions from the royal stores, as demonstrated by a fifth-century BC Aramaic document. governors. Can refer to either the major provincial rulers, called satraps, or to lesser regional governors.

2:8 park. The Hebrew (pardes) is a loanword from Persian that originally meant “beyond the wall,” hence an enclosure, a pleasant retreat, or a park. See note on Est 1:5. the citadel. May refer to the fortress north of the temple. The majority of the construction of these structures would have been mud brick and stone. Cedar timber would have been used primarily for paneling, though the lintel and side-posts of gates would also use beams of wood.

2:10 Sanballat. Sanballat was the chief political opponent of Nehemiah. Although not called governor, he had that position over Samaria (4:1–2). An important Elephantine papyrus, a letter to Bagoas (the governor of Judah), refers to “Delaiah and Shelemiah, the sons of Sanballat the governor of Samaria.” It is interesting that Sanballat’s sons both bear Yahwistic names. Bagoas and Delaiah authorized the Jews to petition the satrap Arsames about rebuilding their temple at Elephantine. Tobiah. He may have been a Judaizing Ammonite, but more probably he was a Yahwist Jew as indicated by his name and that of his son, Jehohanan (6:18). Some scholars speculate that Tobiah descended from an aristocratic family that owned estates in Gilead and was influential in Transjordan and in Jerusalem even as early as the eighth century BC. official. The Hebrew (ebed) is lit. “slave” or “servant.” The RSV believes this term was meant derisively: “Tobias, the Ammonite, the slave.” But ebed is often used of high officials both in Biblical and in extra-Biblical texts. He may have been governor of Ammon, as his grandson (also named Tobiah) was.

2:13 Jackal Well. The Hebrew (en hattannin) is “spring of the dragon,” using the same Hebrew word as Ge 1:21, referring to the chaos creatures of the water (see note on Ge 1:21). The NIV and RSV emend the word to read tannim (“jackals”). It is possible that this may be the major spring of Jerusalem, the Gihon, and that the name “Tannin” is derived from the serpentine course of the waters of the spring to the Pool of Siloam.

2:14 Fountain Gate. Possibly in the southeast wall facing toward En Rogel. According to 2Ki 20:20 (cf. 2Ch 32:30), Hezekiah diverted the overflow from his Siloam tunnel to irrigate the royal gardens (2Ki 25:4; see the article “Hezekiah’s Tunnel”) located at the junction of the Kidron and Tyropoeon Valleys.

2:19 Geshem the Arab. In addition to Sanballat and Tobiah, a new opponent is named, this one an Arab. Biblical and extra-Biblical documents indicate that Arabs became dominant in the Transjordanian area from the Assyrian to the Persian periods. A Lihyanite inscription from Dedan in northwest Arabia reads: “Jašm son of Šahr and ‘Abd, governor of Dedan.” This Jašm is identified with the Biblical Geshem. In 1947, several silver vessels, some with Aramaic inscriptions dating to the late fifth century BC, were discovered near the Suez Canal. One inscription bore the name “Qaynu the son of Gashmu, the king of Qedar.” Geshem was thus in charge of a powerful north Arabian confederacy of tribes that controlled vast areas from northeast Egypt to northern Arabia to southern Palestine.

It is noteworthy that the Edomites, who occupied the territory southeast of Judah, are not mentioned as a foe, though they are denounced particularly by the prophet Obadiah for taking advantage of the Babylonian occupation of Judah. Epigraphic evidence indicates the integration of Edom into the Persian ruled territory of greater Arabia.

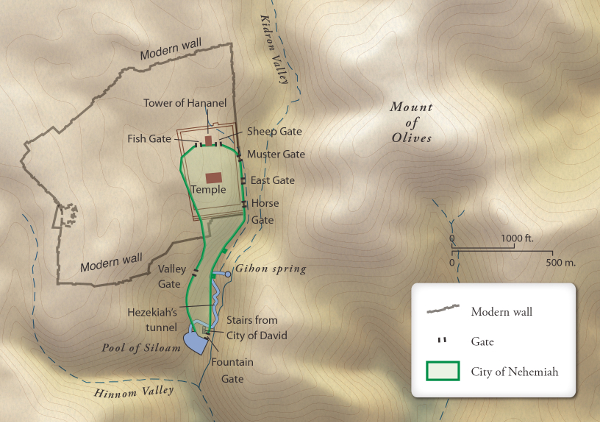

3:1–32 This chapter describes how Nehemiah effectively organized work crews to repair sections of the city wall, beginning at the Sheep Gate in the north and proceeding in a counterclockwise direction for the 1.5-mile (2.4-kilometer) circuit of the wall. Some cities, such as Bethlehem, are not represented; some segments of society, such as “the nobles” of Tekoa, refused to participate (v. 5), but others repaired double sections (v. 27). Archaeological evidence indicates that Nehemiah must have abandoned areas on the steep eastern slope of Ophel. Only one crew was needed to repair the southern half of the western wall (from the Valley Gate to the Dung Gate). On the other hand, the eastern section required twice as many work crews as the western section.

3:1 Eliashib the high priest. He was the son of Joiakim and father of Joiada (12:10). His “house” is mentioned in 3:20–21. It was fitting that the high priest should set the example. Among the Sumerians, the king himself would carry bricks (or at least the ceremonial first brick) for the building of the temple, a practice attested as late as the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. Sheep Gate. The only gate that was “dedicated” by the priests. No doubt, it was used to bring in sheep for sacrifices in the temple. It was located in the northern section of the wall. Jn 5:2 locates a Sheep Gate near the Bethesda Pool, whose ruins have been excavated on the grounds of Saint Anne’s Church near the current Saint Stephen’s Gate in the northeastern part of the Ottoman walls. This may have replaced the earlier Benjamin Gate (Jer 37:13; 38:7) that led to Anathoth in Benjamin (Zec 14:10). Tower of the Hundred. Mentioned only here and in 12:39. What the “hundred” refers to is unclear—its height (100 cubits), or 100 steps, or a military unit (cf. Dt 1:15). Tower of Hananel. Also mentioned in Jer 31:38 and Zec 14:10 as the northernmost part of the city. Some scholars believe that the “Tower of the Hundred” may be a popular name for this tower, but other scholars believe that these were two separate towers, with the Tower of Hananel to the west of the Tower of the Hundred. The towers were associated with “the citadel by the temple” (2:8) in protecting the vulnerable northwestern approaches to the city.

3:3 Fish Gate. Known in the days of the first temple as one of Jerusalem’s main entrances. It may be the same as the Gate of Ephraim (8:16; 12:39), which led out to the main road north from Jerusalem and then descended to the coastal plain through Beth Horon. It was called the Fish Gate, because merchants brought fish either from Tyre or from the Sea of Galilee through it to the fish market.

3:5 Tekoa. A small town five miles (eight kilometers) south of Bethlehem, famed as the home of the prophet Amos (Am 1:1). Some have suggested that its southern location near the territory of Geshem may have meant that the nobles were influenced to cooperate with him. their nobles. These aristocrats disdained manual labor. would not put their shoulders to the work. The Hebrew word for “shoulders” specifically refers to the back of the neck. This expression is drawn from the imagery of oxen that refuse to yield to the yoke.

3:7 under the authority. Lit. “to the chair” or “throne.” Fragments of a lion’s paw and a bronze cylinder that belonged to the foot of a Persian throne similar to those depicted at Persepolis were found in Samaria. The phrase can be interpreted in different ways: (1) as the satrap’s residence in Jerusalem; (2) as the satrap’s residence at Damascus or Aleppo; or (3) with the “chair” as a symbol for the jurisdiction of the governor over the places from which the builders came, such as Mizpah (NIV interpretation).

3:8 one of . . . one of. Reflects the Hebrew word ben (“son of,” i.e., a member of a guild). goldsmiths . . . perfume-makers. The industrial district of the goldsmiths and perfumers may have been located outside the wall. Craft guilds were often made up of families that had perfected their own secrets and techniques that would be passed down from generation to generation. perfume-makers. Translates raqqahim, which occurs only here, with the feminine form in 1Sa 8:13. As demonstrated by other derived forms of the same root and cognates in other Semitic languages, it pertains to mixing ointments and spices. They restored. Comes from the Hebrew word azab, which means “to abandon” (the Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT, uses kataleipo, “to leave”). Some scholars, whose view the NIV has followed, believe that the word here must be a homonym that means “to restore” or “to fortify,” citing words in cognate languages. Nevertheless, it could also mean that Nehemiah abandoned areas as far as the Broad Wall. Broad Wall. Often understood as a thick wall, but it can be interpreted to mean a long, extensive wall. In 1970–1971 a wall about 7.5 yards (7 meters) thick was discovered in the Jewish Quarter of the walled city that was cleared for some 44 yards (40 meters). This wall, dating to the early seventh century BC, was probably built by Hezekiah (2Ch 32:5). It is postulated that the great expansion to and beyond the Broad Wall that caused a three- to fourfold expansion of the city was occasioned by the influx of refugees from the fall of Samaria in 722 BC.

3:11 Tower of the Ovens. This is preferable to the alternative translation: “tower of the furnaces” (e.g., KJV). This tower is mentioned only here and was located on the western wall, perhaps in the same location as the one Uzziah built at the Corner Gate. The ovens may have been those situated in the bakers’ street. Another possibility is that they overlooked the potters’ quarter.

3:12 Hallohesh. The Hebrew (hallohesh) is not a proper name but a participle that means “whisperer,” in the sense of a snake charmer or an enchanter. with the help of his daughters. A unique reference to women working at the wall, which may refer to either his biological daughters or associates who practice divination. When the Athenians attempted to rebuild their walls after the Persians had destroyed them, it was decreed that “the whole population of the city, men, women and children, should take part in the wall-building.” Less likely is the attempt to translate the word “daughters” as “dependent” villages (cf. 11:25–31).

3:14 Beth Hakkerem. Meaning “house of the vineyard,” it is mentioned in Jer 6:1 as a fire signal point.

3:15 Kol-Hozeh. Lit. “everyone a seer”; it may indicate that the family practiced divination. Divination (i.e., the art of foretelling the future) was widely practiced in the ancient world, in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Canaan, Greece and Rome. There are also references to such practices in Israel (see note on Isa 2:6; see also the articles “Magic,” “Practice of Magic”).

3:16 tombs of David. Several references (1Ki 2:10; 2Ch 21:20; 32:33; Ac 2:29) confirm that David was buried in the city area (Ne 2:5), though the site of the royal tombs has not yet been discovered. See note on 1Ki 2:10.

4:2 army of Samaria. The governor of Samaria had an army to aid the Persian king, but it is not certain if the troops mentioned are a garrison regiment or a local militia.

4:7 Ashdod. Along with Ashkelon, Gaza, Ekron and Gath, it was one of the five major Philistine cities (see note on Jdg 3:3) as early as the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 BC). Ashdod was overrun by the Assyrians in 711 BC and was later conquered by the Babylonians. With the Persian conquest, alternate patches of the Palestinian coast were parceled out to the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon, which provided ships for the Persian navy. During this period Ashdod was the most important city so used. As it was inland, it had a separate harbor at the coastal site of Ashdod-Yam.

4:18 trumpet. See note on Jos 6:4.

5:1–19 The economic crisis faced by Nehemiah is described in ch. 5, in the middle of his major effort to rebuild the wall of Jerusalem. Since this building project lasted only 52 days (6:15), some scholars have considered it unlikely that Nehemiah would have called a great assembly (5:7) in the midst of such a project. They suggest that the assembly was called only after the rebuilding of the wall, taking v. 14 as retrospective. Nevertheless, the economic pressure created by the rebuilding program may have brought to light problems long simmering that had to be solved before work could proceed. Among the classes affected by the economic crisis were the landless, who were short of food (v. 2), the landowners compelled to mortgage their properties (v. 3), those forced to borrow money at exorbitant rates because of oppressive taxation (v. 4), and those forced to sell their children into slavery (v. 5).

5:1 raised a great outcry. The gravity of the situation is underscored in that the wives joined in the protest as the people ran short of funds and supplies to feed their families. This may have been exacerbated by people being required to work the wall instead of their fields during critical harvest time. Also significant, their complaints were not lodged against the foreign authorities, but against their own fellow countrymen, who were exploiting their poorer brethren at a time when both were needed to defend the country.

5:4 king’s tax. See note on Ezr 4:13.

5:5 our daughters have already been enslaved. In times of economic distress, families would borrow funds using members of the family as collateral. If a man could not repay the loan and its interest, his daughters, his sons, his wife or even the man himself could be sold into bondage. A Hebrew who fell into debt would serve his creditor as a hired servant (see note on Lev 25:39). He was to be released in the seventh year, unless he chose to stay voluntarily. The Code of Hammurapi limited such bond service to three years. The ironic tragedy of the situation for the exiles was that at least in Mesopotamia their families were together; now, because of dire economic necessities, their children were being sold into slavery.

5:7 You are charging your own people interest! The Hebrew word mashsha, which occurs only here, in v. 10 and in 10:31, does not technically mean the exaction of interest, often at exorbitant rates. Rather, it means to impose a burden or claim for repayment of debt because a loan has been made for a pledge. Compare the related word mashshaah (“secured loan based on security”; Dt 24:10; Pr 22:26). Nehemiah is therefore lamenting the abuse of a system of loans secured by pledges. A letter on a Hebrew ostracon from Mesdad Hashavyahu on the coast (seventh century BC) bears the poignant plea of a poor farmer whose garment had been taken by the governor’s officer and had not been returned (in contravention of Ex 22:26–27). The OT passages prohibiting the giving of loans at interest were intended not to prohibit commercial loans but rather to prohibit charging interest to the impoverished so as to make a profit from the helplessness of one’s neighbors (see notes on Lev 25:36; Dt 23:19–20).

5:8 you are selling your own people. Though it was possible to use a poor fellow Israelite as a bondservant, he was not to be sold as a slave (Lev 25:39–42). The sale of fellow Israelites as slaves to Gentiles was a particularly callous offense and was always forbidden (Ex 21:8). Joseph’s brothers nonetheless sold him to the foreign traders (Ge 37:12–36). We know from Joel 3:6 that Jews were being sold to Greeks (c. 520 BC).

5:10 lending the people money and grain. The granting of loans is not condemned, nor is the making of profit (cf. Sirach 42:1–5a). Nonetheless, in view of the urgency of the situation, Nehemiah urges the creditors to relinquish their rights to repayment with interest. Solon, the great Athenian reformer (594 BC), adopted a similar policy.

5:11 one percent. Lit. the “hundred” (pieces of silver). But in the context it must mean one percent of interest (i.e., per month).

5:15 earlier governors. “Governors” is the plural of Hebrew pehah (also the same in Aramaic), which is used of Sheshbazzar, Zerubbabel and various Persian officials. It was once believed that Judah did not have governors before Nehemiah, and that this refers to governors of Samaria. New archaeological evidence, however, confirms that the reference is to previous governors of Judah. A collection of bullae (seal impressions) yields the names of some of the governors prior to Nehemiah.

5:18 some poultry. Poultry were domesticated in the Indus River Valley by 2000 BC and were brought to Egypt by the reign of Thutmose III (fifteenth century BC). Poultry were known in Mesopotamia and Greece by the eighth century BC. The earliest evidence in Palestine is the seal of Jaazaniah (c. 600 BC), which depicts a fighting cock. food allotted to the governor. As governor, Nehemiah is expected to entertain both domestic and foreign dignitaries, as well as pay the salaries of the 150 officials (v. 17). The cost of this is supposed to be offset by the “food allotted to the governor” (taxes levied, cf. v. 14), which Nehemiah has refrained from collecting, meaning that these “business expenses” are coming out of his own pocket.

5:19 Remember me with favor. Some have suggested that Nehemiah’s memoirs were inscribed as a memorial set up in the temple. A parallel to Nehemiah’s prayer is found in Nebuchadnezzar II’s prayer to his god: “O Marduk, my lord, do remember my deeds favorably as good [deeds], may (these) my good deeds be always before your mind.” An even more striking parallel is found on the stele of a chief physician named Udjahorresnet in which he identifies himself as a good man who provided relief and protection for his people. He therefore calls on his god to remember his altruism, treat him well and make his name endure, as Nehemiah also does.

6:2 Ono. Located 27 miles (43.5 kilometers) northwest of Jerusalem and 7 miles (11 kilometers) southeast of Joppa, near Lod (Lydda). It was in the westernmost area settled by the returning Jews (7:37; 11:35; Ezr 2:33). There is disagreement among scholars as to whether Ono was part of Judah.

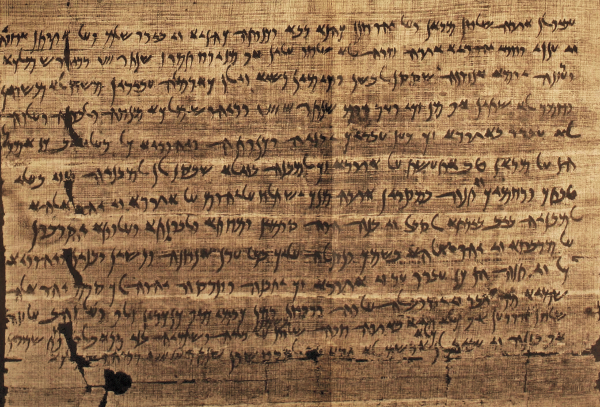

6:5 unsealed letter. Letters during this period were ordinarily written on a papyrus or leather sheet, rolled up, tied with a string and sealed with a clay bulla (seal impression) to guarantee its authenticity (see note on 1Ki 21:8). Sanballat obviously intended that the contents should be made known to the public at large.

6:7 prophets to make this proclamation. See note on 1Ki 11:30.

6:9 hands will get too weak. This idiom uses the Hebrew verb rapah (“to become slack”). The Hebrew idiom “to cause the hands to drop” means to demoralize (cf. Ezr 4:4). Jeremiah was accused of “weakening the hands of the soldiers” (Jer 38:4; NIV “discouraging the soldiers”). The Lachish Ostracon VI speaks of people in Jerusalem “who weaken the hands of the land and make the city slack so that it fails.”

7:2 commander of the citadel. See note on 4:2.

7:3 gates . . . are not to be opened until the sun is hot. Normally the gates of a city were opened at dawn. According to one view, in this ruling the opening was to be delayed until the sun was high in the heavens, perhaps due to a shortage of gatekeepers to staff the entrance for a full day. Others believe that the gates were to be closed during the heat of the day while people took a siesta. One famous historical episode, which occurred in 410 BC, that may illustrate the need for a special guard at this time was the attack by Alaric on a gate in Rome while the guards were dozing.

7:4 large and spacious. The Hebrew phrase uses the idiom “wide of two hands and large.” This expression means extending to the right and left. As the actual circuit of the wall of the city was smaller than in preexilic times, the expressions must be relative to the number of people who could still be housed once the damaged homes were rebuilt.

7:5 I found the genealogical record. See note on Ezr 2:59; see also the article “The Significance of Genealogies for a Postexilic Audience.”

7:70 1,000 darics of gold. About 19 pounds (8.4 kilograms) of gold.

7:72 20,000 darics of gold. About 375 pounds (170 kilograms) of gold. 2,000 minas of silver. About 1.25 tons (1.1 metric tons) of silver.

7:73 settled in their own towns. Many returning exiles may not have been from Jerusalem. These naturally returned to their own hometowns, leaving Jerusalem underpopulated.

8:1 teacher of the Law. The Hebrew uses the word usually translated “scribe.” The NIV decision to render it “teacher of the Law” reflects the idea that at this period the scribes were taking on a more extensive role (similar to the role played by those called the scribes in the Gospels). Some interpreters see in this development the beginning of what might be referred to as Rabbinic Judaism. Rabbis are recognized as those who instruct the people in the law and lead the synagogues that begin developing around this time as houses of prayer and study distinct from the temple. They gave official interpretations of the text of the law and advised people about how to live in accordance with the law.

8:2 Book of the Law of Moses. There are at least four views about what this book represented: (1) a collection of legal documents, (2) the collection of priestly writings, (3) the laws from what we know as the book of Deuteronomy or (4) the Pentateuch as a whole (Genesis–Deuteronomy). Ezra could certainly have brought back with him the Torah, i.e., the Pentateuch, which is the view now favored by most scholars. What we recognize as the books of the Torah, and the Torah itself, would likely have been compiled over time from individual documents (scrolls, tablets, etc.) that had been archived and repeatedly taught and recopied since the time of Moses.

8:3 read it aloud. See the articles “Literacy,” “Books and Literacy.” Most people in the ancient world, though having basic literacy, did not themselves read documents. They would have had little access to documents and would not need to gain information this way. It was general practice that even those who could read would have documents read aloud to them. Documents were written either to be stored in archives or to be read aloud to others.

8:5 opened the book. See the article “Books and Literacy.”

8:7–8 instructed the people . . . making it clear and giving the meaning. See note on v. 1.

8:15 branches from olive and wild olive trees . . . myrtles, palms and shade trees. With the exception of palm trees and other leafy trees, the trees mentioned here are not the same as those prescribed in Lev 23:40. Lev 23:40 includes the willow, which is omitted here. olive . . . trees. Widespread in Mediterranean countries. According to Dt 8:8, it was growing in Canaan before the conquest. It takes an olive tree 30 years to mature, so its cultivation requires peaceful conditions. wild olive trees. Rendered “oil trees” (Olea europaea oleaster) by the NKJV and “oleaster” by the NABRE. However, this is questionable, since, according to 1Ki 6:23, 31–32, the wood of this tree was used as timber, whereas the wood of the wild olive tree had little value for use in the temple’s furniture. Also, the oleaster contains very little “oil.” The phrase may have meant a resinous tree like the fir. The KJV renders the phrase as “pine.” myrtles. Evergreen bushes with a pleasing odor. palms. Date palms; such trees were common around Jericho.

9:6 You alone are the LORD. See the article “Monotheism, Monolatry and Henotheism.” The reference here is to the personal name of the God of Israel, Yahweh. Since no other god claims the name Yahweh, this should be rendered to convey that Yahweh stands alone—in a class by himself. The description that follows in the prayer (vv. 6–37) enumerates the unique acts of Yahweh that distinguish him from other gods. Though the prayer begins with acts of creation that other peoples would attribute to other gods, most of the list deals with the acts Yahweh performed on behalf of his covenant people Israel. starry host. See note on 2Ki 21:3.

9:18 image of a calf. See note on 1Ki 12:28; see also the article “The Golden Calf.”

9:22 Sihon king of Heshbon. See note on Dt 2:24.

9:25 wells already dug. The lack of rainfall during much of the year made it necessary for almost every house to have its own well or cistern to store water from the rainy seasons. See note on Ge 37:20.

9:32 kings of Assyria. One of these was Shalmaneser III (858–824 BC), who reported that he defeated Ahab at the battle of Qarqar in 853 BC, an important battle, but one that is not mentioned in the OT (see the article “Omri and Jehu in History”). The first Assyrian king to expand his empire to the Mediterranean was the great Tiglath-Pileser III, also known as Pul. He attacked Phoenicia in 736 BC, Philistia in 734 and Damascus in 732 (see note on 2Ki 15:29; see also the article “Israel and Damascus Versus Judah”). Early in his reign (752–742 BC), Menahem of Israel paid tribute to him (see note on 2Ki 15:19). During his campaigns against Damascus, he also ravaged Gilead and Galilee and destroyed Hazor and Megiddo. Shalmaneser V (727–722 BC) laid siege to Samaria (see the article “Shalmaneser”)—a task completed by Sargon II (721–705 BC) (see the article “Hezekiah and Assyria”). Sennacherib (704–681 BC) failed to take Jerusalem in 701 BC, but captured Lachish (see notes on 2Ki 18:13, 14; 19:9, 36). Esarhaddon (681–669 BC) conquered Lower Egypt and extracted tribute from Manasseh of Judah (see note on 2Ki 19:37). Ashurbanipal (669–633 BC) also invaded Egypt and proceeded as far south as Thebes. He was probably the king who freed Manasseh from exile and restored him as a puppet king (see the article “Manasseh of Judah and Ashurbanipal”).

9:37 bodies. The Hebrew term is used 13 times in the OT and characterizes the human being in weakness, oppression or trouble. It is also used of a “corpse” (e.g., see 1Sa 31:10 [“body”]) or of a “carcass” (e.g., Jdg 14:9). The Persian rulers drafted their subjects into military service. Possibly some Jews accompanied Xerxes on his invasion of Greece.

10:1–27 This is a legal list, bearing the official seals and containing a roster of 84 names arranged according to the following categories: 2 leaders, 21 priests, 17 Levites and 44 laymen.

10:30 See the article “Mixed Marriages.”

10:31 we will not buy . . . on the Sabbath. Though the Sabbath passages in the Torah (e.g., Ex 20:8–11; Dt 5:12–15) do not explicitly prohibit trading on the Sabbath, this is clearly understood in Jer 17:19–27; Am 8:5. The provisions of Ne 10:31–34 may have been a code drawn up by Nehemiah to correct the abuses listed in ch. 13 (e.g., 13:15–22). Most of the topics addressed in ch. 10 correspond with those found in ch. 13: mixed marriages (compare 10:30 with 13:23–30), Sabbath observance (compare 10:31 with 13:15–22), wood offering (compare 10:34 with 13:31), firstfruits (compare 10:35–36 with 13:31), Levitical tithes (compare 10:37–38 with 13:10–14) and neglect of the temple (compare 10:39 with 13:11). Every seventh year we will forgo working the land. See note on Lev 25:2.

10:32 a third of a shekel. Ex 30:13–14 states that “a half shekel . . . is an offering to the LORD” to be given by each man “twenty years old or more” as a symbolic ransom. Persian subsidies for the temple (Ezr 6:9–10; 7:21–24) had probably lapsed by this time.

10:33 for the bread set out on the table. See note on Ex 25:30.

10:34 contribution of wood. Though there is no specific reference to a wood offering in the Pentateuch, the perpetual burning of fires would have required a continual “contribution of wood.”

10:35 firstfruits. See note on Nu 18:12.

10:37 tithe of our crops. Lit. “tithe of our land.” The law decreed that a tenth of the plant crops was holy to the Lord (Lev 27:30; Nu 18:23–32). There is no reference here to a tithe of cattle (as in Lev 27:32–33; cf. 2Ch 31:6). Earlier in the fifth century BC, the prophet Malachi accused the Israelites of robbing God by withholding tithes and offerings (Mal 3:8). Tithes were originally meant for the support of the Levites (Ne 13:10–12; Nu 18:21–32). A tithe of their tithe was to go to the priests. But we know from Josephus that later on the priests collected the tithes for themselves. Because the tithe was originally expressed in terms of agricultural produce, the burden of the tithe fell disproportionately on farmers.

11:1 one out of every ten. The need for the repopulation of Jerusalem is expressed in 7:4. The practice of redistributing populations was also used to establish Greek and Hellenistic cities. Known as synoikismos, the practice involved the forcible transfer from rural settlements to urban centers. The city of Tiberias on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee was populated by such a process by Herod Antipas in AD 18. Archaeological surveys indicate a drop of over 75 percent of the number of occupied sites as a result of the Babylonian conquest of Judah. That they “cast lots” indicates that people do not wish to live in Jerusalem. Since the city is still in a state of disrepair and a focal point of enemy aggression, it is neither a safe nor an attractive place to live. People would also be unwilling to abandon their farms or jeopardize their landholdings.

11:9 New Quarter. Translates Hebrew mishneh, which some English versions transliterate simply as “Mishneh.” Like the “market district” (maktesh) in Zep 1:11 (probably the Tyropoeon Valley area), the Mishneh was a new suburb to the west of the temple area.

11:10 the priests. To be qualified as a priest, one had to establish his descent through genealogical records, which would trace his ancestry all the way back to Aaron, Moses’ brother and the first priest. Hence, priestly genealogies play an important role in the books of Ezra, Nehemiah and Chronicles (see the article “The Significance of Genealogies for a Postexilic Audience”).

11:20 ancestral property. Designates the inalienable hereditary possession including land, buildings and movable goods acquired either by conquest or inheritance. In the OT it describes the land of Canaan as the possession of both Yahweh and Israel, including the individual holdings of tribes and families. It also designated Israel as Yahweh’s special possession (see note on Dt 7:6).

11:24 Pethahiah . . . was the king’s agent in all affairs relating to the people. Scholars are unsure of the rank of this individual. He may have been a governor who succeeded Nehemiah, or perhaps he was a representative of the interests of the people to the provincial governors or satraps. He may have alternatively represented the Jews at the imperial court in Persia.

11:25–35 There are 17 locations in Judah and 15 in the adjoining territory to the north of Benjamin in these verses. The former locations correspond to earlier lists of Judahite cities. All these names also appear in Jos 15 (except Dibon, Jeshua and Mekonah). The settlements to the south were in areas that were outside the boundary of the province of Yehud, under the influence if not control of the Edomites or Arabs. The list, however, is not comprehensive insofar as several cities listed in Ezr 2:20–34 and Ne 3 are lacking. The limits of the Judahite settlement after the return from Babylon have been confirmed by archaeological evidence; none of the YHD-YHWD (the official designation of the Persian province of Judea) coins have been found outside the area demarcated by these verses.

11:25 Kiriath Arba. The archaic name of Hebron (Jos 20:7), an important city 20 miles (32 kilometers) south of Jerusalem (see note on Nu 13:22).

11:30 Lachish. See notes on 2Ki 14:19; 18:14.

11:35 Ge Harashim. Also known as The Valley of the Craftsmen, this may be the Wadi esh-Shellal, the broad valley between Lod and Ono. The oak trees of the nearby Sharon plain would have been useful to artisans working in either wood or iron.

12:22 Darius the Persian. Though some have favored either Nothus (Darius II, 423–404 BC) or Codomannus (Darius III, 335–331 BC, the king whose empire Alexander the Great conquered), the writer probably intended to designate Darius I as “the Persian” in opposition to the enigmatic “Darius the Mede” of Daniel (see note on Da 5:31).

12:27 cymbals, harps and lyres. See the article “Music and Musicians.”

12:30 purified . . . the wall. This idea is unprecedented in the Bible, since purification usually involves consecrating objects or locations used in rituals, though houses with mildew need to be purified (Lev 14:48–53; see note on Lev 14:34). If the former sense is meant, the purification could be the act of consecrating Jerusalem as a “holy city”; if the latter, it may be to remove the corruption of the devastation (corpse contamination, etc.) or the impurity of the idolatry that had been performed there.

13:1 Book of Moses was read . . . no Ammonite or Moabite should ever be admitted into the assembly of God. See Dt 23:3–6.

13:2 Balaam. See the article “Balaam.”

13:6 I was not in Jerusalem. The Elephantine papyri provide us with an interesting parallel to Nehemiah’s absence. Arsames, the satrap of Egypt, left his post in the 14th year of Darius II (410/409 BC) and was still absent at the Persian court in the 17th year (407/406 BC)—i.e., for three years. As in Nehemiah’s case, internal conflict and a breakdown of order took place during the governor’s absence.

13:8 I was greatly displeased. Nehemiah’s expulsion of Tobiah is paralleled somewhat earlier in Egypt by Udjahorresnet’s expulsion of squatters from the temple of Neith at Sais. Since wealth, power and prestige were all connected to the temples of the ancient world, it was not uncommon for unsavory and undesirable individuals to infiltrate and exploit the temple for their own gain. Reformers would naturally want to expel such people.

13:16 Tyre. In modern times it is located only about 12 miles (19 kilometers) north of the border between Israel and Lebanon. Tyre was renowned for its far-flung maritime trade (see notes on 1Ki 5:1; 2Ch 8:18.

13:19 When evening shadows fell on the gates . . . before the Sabbath. The gates began to cast long “evening shadows” even before sunset, when the Sabbath began. The Israelites, like the Babylonians, counted their days from sunset to sunset (the Egyptians reckoned their days from dawn to dawn). The precise moment the Sabbath began was heralded by the blowing of a trumpet by a priest.

13:24 language of Ashdod. The excavations at Ashdod have uncovered an ostracon from Nehemiah’s age in Aramaic script that reads krm zbdyh (“[from the] vineyard of Zebadiah”). Unfortunately, the inscription is too brief to shed any light on the Ashdodite language. Possibly the dialect was Phoenician. In the Persian period the Philistine-Palestinian coastal area was divided into several jurisdictions. Ashkelon was under the Tyrians; Ashdod was the center of the Persian province.

13:25 pulled out their hair. Contrast Ezra’s action (Ezr 9:3), who pulled out his own hair, with Nehemiah’s here. Plucking the hair from another’s beard was designed to show anger, express an insult and mark someone as worthy of scorn (cf. 2Sa 10:4; Isa 50:6). The semirasus (“half-shaven”) marked the lowest type of slave or prisoner in Rome. Nehemiah’s action was designed to prevent future intermarriages (“you are not to give”), whereas Ezra dissolved the existing unions (Ezr 10:1–5).

13:26 Solomon king of Israel sinned. See 1Ki 11:1–6 and notes.

13:28 One of the sons of Joiada son of Eliashib the high priest was son-in-law to Sanballat. The Hebrew is ambiguous since the phrase “high priest” can refer to either Joiada or Eliashib. In the latter case, Eliashib was still alive. More likely, however, “high priest” designates Joiada (cf. 12:10). The offending son would then have been a brother of the man who succeeded Joiada as high priest, Johanan II (12:22–23), who was married to a daughter of Sanballat. According to Lev 21:14, the high priest was not to marry a foreigner. The expulsion of Joiada’s son may have followed this special ban or the general interdict against intermarriage. Such a union was especially rankling to Nehemiah in the light of Sanballat’s enmity.