Annotations for Ezra

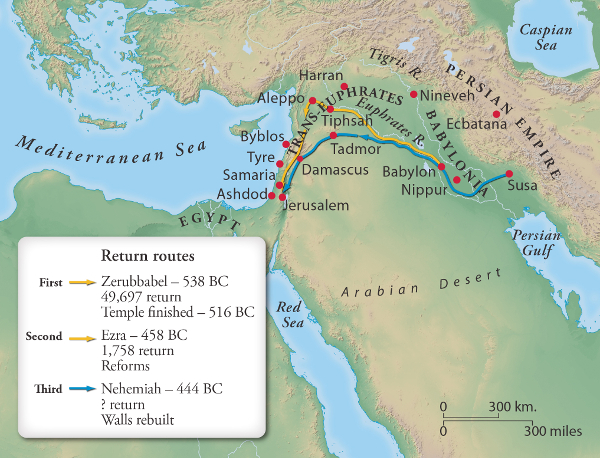

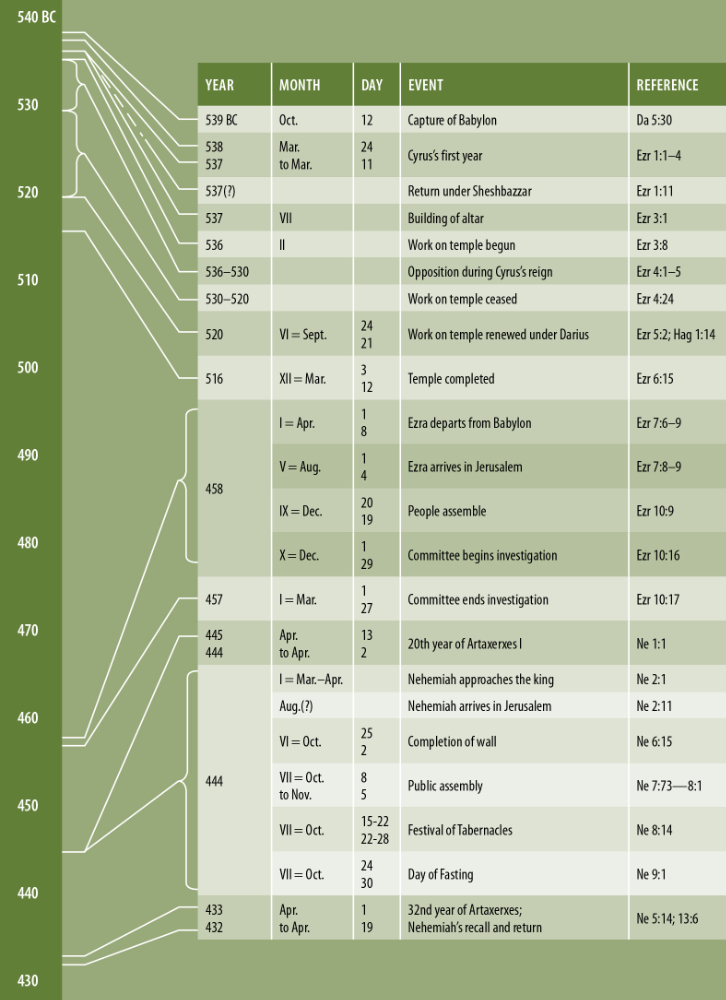

1:1 first year of Cyrus king of Persia. When Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon in 539 BC and established Persian rule in the ancient world, he set in motion a series of events important for the Jews. His proclamation recorded in vv. 2–4 and 2Ch 36:23 gave permission for the rebuilding of the temple in Jerusalem, which resulted in a series of returns from exile by deportees and the descendants of deportees. Although the Jews regarded Cyrus as a benefactor, as well they might, it should be noted that his “beneficence” was not directed solely toward the Jews, but formed part of a wider foreign policy. The Cyrus Cylinder, in which Cyrus decrees that some exiled populations can return, mentions a number of deities and peoples whom he restored to their own places. The thinking behind this, no doubt, was to foster goodwill among the subjects of his kingdom. This was especially desirable in the case of the province of Yehud, since it lay on the fringe of the empire and acted as a buffer between an Egypt that had not yet been subjugated and the rest of the realm. Through the decree of Cyrus (see note on 2Ch 36:22–23), those exiled to Babylonia were given the opportunity to return home and rebuild what was left of Judah (Ezr 2:1–35; Ne 7:5–73). the word of the LORD spoken by Jeremiah. Jeremiah’s prediction (Jer 25:1–12; 29:10; cf. 51:11) of a 70-year Babylonian captivity. The first deportations began in 605 BC, in the third year of Jehoiakim (Da 1:1). The 70th year would be 536 BC.

1:2 God of heaven. This title ascribed to Yahweh does not necessarily reflect Cyrus’s personal beliefs. In the Cyrus Cylinder, he attributes his conquest of Babylon to the city’s patron, Marduk. Marduk, Yahweh and any other gods would have been seen by Cyrus as members of the forces of light under the head of Ahura Mazda, the god of the Persian Zoroastrian religion. Similar deference is made to other gods in decrees pertaining to the restoration of their shrines.

1:7 articles belonging to the temple of the LORD. Conquerors customarily carried off the statues of the gods of conquered cities (see note on 1Sa 5:2). The Cyrus Cylinder records Cyrus returning sacred objects throughout his empire: “I returned the (images of) the gods to the sacred centers [on the other side of] the Tigris whose sanctuaries had been abandoned for a long time, and I let them dwell in eternal abodes. I gathered all their inhabitants and returned (to them) their dwellings.”

1:8 Sheshbazzar. This little-known individual should not be confused with the Davidic descendant Shenazzar (1Ch 3:18), despite scholarly attempts to make that identification. prince of Judah. This title could refer to a position in the Davidic line, or it could be seen as a title indicating his position as custodian of the exiles until control is passed to the local governor, Zerubbabel. Archeologists have uncovered seals naming three governors of Judah who are otherwise unknown even in the text of Ezra-Nehemiah.

1:9–11 The inventory of plunder taken was carefully tabulated by the Assyrians and Babylonians, and no doubt by the Persians as well, though we lack similar records from them. As there was no idol in the Jewish temple, the closest substitute would have been the ark of the covenant. But this was evidently destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar, as we no longer hear of it. Based on the legendary Kebra Negast tradition that the queen of Sheba’s son Menelik stole the ark from Solomon, Ethiopian Christians claim that they possess the ark in their cathedral in Aksum.

2:21–35 These verses list a series of villages and towns, most of them in Benjamite territory north of Jerusalem. Those represented by villages rather than families may have represented “the poorest people of the land” (2Ki 25:12), who had no land or property in their own name.

2:40 Levites. Descendants of Levi (cf. Ge 29:34). They may have originally been regarded as priests (Dt 18:6–8), but they became subordinate to the priestly descendants of Aaron, brother of Moses (Nu 3:9–10; 1Ch 16:4–42; 23:26–32). The Levites were then prohibited from offering sacrifices on the altar (Nu 16:40; 18:7). The number of Levites who returned (74) is remarkably small as compared with over 4,000 priests (vv. 36–39). When Ezra was ready to lead a group from Babylon in 458 BC, he had to stop to enlist Levites (8:15). Either few Levites had been deported because they belonged to the poorer class, or they may have turned to secular occupations during their exile.

2:43 temple servants. A long list of names (35 in vv. 43–54; 32 in Ne 7:46–56) follows the heading “temple servants.” The Hebrew word used here occurs only in 1Ch 9:2 and in Ezra-Nehemiah. They occupied a special quarter in Jerusalem (Ne 3:26, 31; 11:21) and enjoyed exemption from taxes (Ezr 7:24). They participated in rebuilding the wall (Ne 3:26) and signed Nehemiah’s covenant (Ne 10:29).

2:59 they could not show. Of the exiles who returned, members of three lay families and three priestly families were unable at this time to prove their descent. Some may have derived from proselytes; others may have temporarily lost access to their genealogical records. Genealogies, which occur prominently in Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah, were important for many reasons, but especially for priests and Levites. See the article “The Significance of Genealogies for a Postexilic Audience.”

2:61 Barzillai. The case of a man taking his name from his father-in-law is unique in the OT, but it is attested in Mesopotamia as a so-called erebu marriage; it is also attested in many other cultures (such as the Japanese), where a family has daughters but no sons.

2:63 Urim and Thummim. See the article “Urim and Thummim.”

2:69 darics. The daric was a gold Persian coin, named after Darius I, who began minting it. The coin was famed for its purity, which was guaranteed by the king. It bore the image of an archer and weighed about one-tenth of a gram.

3:2 Joshua . . . and Zerubbabel. Scholars have seen a tension between this statement and that of 5:16, which states that Sheshbazzar laid the foundations for the temple. Moreover, Haggai, who dates his prophetic activity in Hag 1:1 to the “second year of King Darius” (520 BC), mentions Zerubbabel (Hag 1:1) but not Sheshbazzar. It is possible that a foundation laid by Sheshbazzar had deteriorated over 20 years and had to be done again.

3:4 Festival of Tabernacles. See the article “Festivals.”

3:7 cedar logs . . . from Lebanon. As with Solomon’s temple (1Ch 22:2–4; 2Ch 2:7–15), the Phoenicians cooperated by sending timbers and workmen (1Ki 5:7–12). See notes on 2Sa 5:11; 1Ki 5:6; 6:15.

4:2 we seek your God. The people who proffered their help were evidently from the area of Samaria, though they are not explicitly described as such. After the fall of Samaria in 722 BC, the Assyrian kings kept importing inhabitants from Mesopotamia and Syria who “worshiped the LORD, but . . . also served their own gods” (2Ki 17:33). The newcomers’ influence doubtless diluted further the faith of the northerners, who had already apostatized from the sole worship of the Lord in the tenth century BC. Even after the destruction of the temple, worshipers from Shiloh and Shechem in the north came to offer cereals and incense at the site of the ruined temple (Jer 41:5). Moreover, the northerners did not abandon faith in Yahweh, as we see from the Yahwistic names given to Sanballat’s sons (Delaiah and Shelemiah) in the Elephantine papyri. Nevertheless, they retained Yahweh not as the sole God, but as one god among many gods. Sanballat’s name honors the moon-god Sin. Though Ezra-Nehemiah does not explicitly mention the syncretistic character of the northerners, evidence suggests that the inhabitants of Samaria were syncretists. Esarhaddon king of Assyria. See note on 2Ki 19:37.

4:6 Xerxes. See Introduction to Esther: Historical Setting.

4:7 Artaxerxes. Artaxerxes I (465–424 BC), the Persian king during whose reign both Ezra and Nehemiah led the Jewish exiles. Little is known of him from sources outside the Hebrew Bible. Herodotus makes passing reference to his disastrous economic policies. Several revolts were unsuccessful at unseating him, but they did occupy his attention.

4:10 Ashurbanipal. See the article “Manasseh of Judah and Ashurbanipal.”

4:11 Trans-Euphrates. Lit. “across the River.” This place-name first appears in the reign of Sargon II. Those living west of the Euphrates River, who looked east across the Euphrates, defined the land “across the River” as Mesopotamia (Jos 24:2–3, 14–15; 2Sa 10:16). Mesopotamians, who looked west across the Euphrates, saw this region as including Syria, Phoenicia and Israel—the area today referred to by historians of the ancient world as the Levant (cf. 1Ki 4:24).

4:13 taxes. Translates a Hebrew (and Aramaic) term borrowed from Akkadian that refers to a fixed annual tax paid by the provinces to the king. The word appears in the Elephantine texts as the rent due from the royal domains in Egypt to the Persians. Estimates suggest that 20–35 million dollars’ worth of taxes were collected annually by the Persian king. The Fifth Satrapy, which included the Jewish province of Yehud, had to pay the smallest amount of the western satrapies. The Persians took much of the gold and silver coins and melted them down to be stored as bullion. Very little of the taxes returned to benefit the provinces. tribute. The rent tax in Babylonia. Some scholars interpret this word as an impost or duty charged on merchandise (RSV “custom”) or as a poll tax. duty. Derives from Akkadian and was a land tax.

4:23 compelled them by force to stop. After provincial authorities had intervened, the Persian king ordered a halt to the Jewish attempt to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem. Most scholars date the episode of vv. 7–23 to just before 445 BC. The forcible destruction of these recently rebuilt walls rather than the destruction by Nebuchadnezzar is the basis of the report made to Nehemiah (Ne 1).

4:24 Darius king of Persia. During his first two years, Darius fought numerous battles against nine rebels. Only after the stabilization of the Persian Empire could efforts to rebuild the temple be permitted. Darius consolidated the administration of the vast empire, setting up satraps, introducing coinage and establishing the famous royal road from Susa to Sardis and a system of mounted couriers.

5:1 Haggai . . . and Zechariah . . . prophesied. Very little progress had been made in the years since the foundation of the temple was first laid. But beginning on Aug. 29, 520 BC (Hag 1:1), and continuing till Dec. 18 (Hag 2:1–9, 20–23), the prophet Haggai delivered a series of messages to stir the people to begin work on the temple. Two months after Haggai’s first speech, Zechariah joined him (Zec 1:1). Hag 1:6 describes the deplorable situation: housing shortages, disappointing harvests, lack of clothing and jobs, and inadequate funds—perhaps as a result of inflation. Money went into “a purse with holes in it.” The people were concerned more about their own houses than about the Lord’s house. See the article “Prophets and Prophecy.”

5:2 Zerubbabel. A Babylonian name referring to his birth in exile, probably before 570 BC. Here (see also Ezr 3:2; Ne 12:1; Hag 1:1) he is described as the “son of Shealtiel.” Shealtiel. Son of Jehoiachin, second-to-last king of Judah (1Ch 3:17). Though he was replaced by Zedekiah, Jehoiachin was regarded as the last legitimate king of Judah. Zerubbabel was the last of the Davidic line to be entrusted with political authority by the occupying powers.

5:3 Tattenai, governor of Trans-Euphrates. Attestation of this governor (see also v. 6; 6:6, 13) has been provided by a cuneiform document that can be dated to June 5, 502 BC, which cites Tattannu as the governor who was subordinate to the satrap over the region of Ebir-nari. From the Mesopotamian point of view, the region “across the River” was the area west of the Euphrates River, including Syria and Palestine (see note on 4:11). Tattenai was a subordinate of the governor of the combined satrapy of Across-the-River and Babylonia.

5:7 The report they sent . . . King Darius. That such inquiries were sent directly to the king has been vividly confirmed by the Elamite texts from Persepolis, where in 1933–1934 several thousand tablets and fragments were found in the fortification wall. Some 2,000 fortification tablets, dated from the 13th to the 28th year of Darius (509–494 BC), deal with the transfer and payment of food products. In 1936–1938, over 100 additional Elamite texts were discovered in the treasury area of Persepolis, dating from the 30th year of Darius to the 7th year of Artaxerxes I (492–458 BC). In addition to payment in kind, they include supplementary payment in silver coins, an innovation introduced around 493 BC.

6:2 Ecbatana. The capital of Media. Its ancient name is still preserved in the name of the modern Hamadan in northwestern Iran. This is the sole OT reference to the site, though there are numerous references in the Apocryphal books. Memorandum. A similar “memorandum” in the Aramaic papyri deals with Persian permission to rebuild the Jewish temple at Elephantine, which Egyptians had destroyed. It includes a response from the Persian governor to a petition from the Jewish garrison serving the Persians on the island of Elephantine near Aswan in Upper Egypt.

6:4 three courses of large stones and one of timbers. See note on 1Ki 6:36.

6:7 on its site. When Babylonian kings such as Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus rebuilt temples, they searched carefully to discover the exact outlines of the former buildings. An inscription of Nabonidus reads: “I discovered its [i.e., the Ebabbara in Sippar] ancient foundation, which Sargon, a former king, had made. I laid its brick foundations solidly on the foundation that Sargon had made, neither protruding nor receding an inch.” See note on 2Ki 12:5 (“repair . . . the temple”).

6:8 Their expenses are to be fully paid out of the royal treasury. As the accounts in Haggai and Zechariah do not speak of support from the Persian treasury, some have questioned the promises made here. Extra-Biblical evidence, however, makes it clear that Persian kings consistently helped restore sanctuaries in their empire. Cyrus repaired the Eanna temple at Uruk and the Enunmah structure at Ur. Cambyses gave funds for the temple at Sais in Egypt, according to the important inscription of Udjahorresnet. The temple of Amon at Hibis in the Khargah Oasis was rebuilt from top to bottom by order of Darius.

6:10 so that they may offer sacrifices . . . and pray. Darius commanded that the Jews be allowed to “pray for the well-being of the king and his sons.” In the Cyrus Cylinder the king asks, “May all the gods whom I have resettled in their sacred cities ask daily Bel and Nebo for a long life for me.” The Jews of Elephantine wrote to Bagoas, the Persian governor of Judah, that if he helped them get their temple rebuilt, “the meal-offering, incense and burnt offering will be offered in your name, and we shall pray for you at all times, we, and our wives and our children.” Herodotus reported that among the Persians anyone who offered a sacrifice had to pray for the king.

6:11 impaled. See note on Est 2:23.

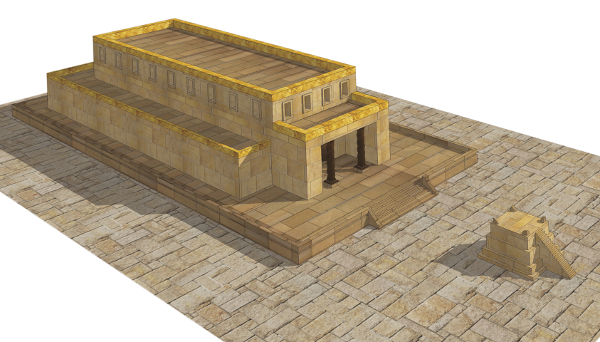

6:15 third day of the month Adar. The temple was finished on Mar. 12, 515 BC, a little over 70 years after its destruction. As the renewed work on the temple had begun in September, 520 BC (see Hag 1:4–15), sustained effort had continued for over four years. According to Hag 2:3, the older members, who could remember the splendor of Solomon’s temple, were disappointed when they saw the smaller size of Zerubbabel’s temple. Nonetheless, the second temple, though not as grand as the first, lasted much longer.

6:18 priests in their divisions. As there were more priests than necessary for services in the Jerusalem temple, they were divided into rotations. There are 21 rotations mentioned in Ne 10:3–9; 24 in 1Ch 24:1–19. Since the priests served a week at a time, they normally served at Jerusalem twice a year.

6:20 ceremonially clean. See notes on Lev 21:1; 22:3–9.

6:21 all who had separated themselves. The returning exiles were not uncompromising separatists; they were willing to accept those who separated themselves from the syncretism of the foreigners introduced into the area by the Assyrians. Gentiles, such as Rahab and Ruth, who were willing to join themselves to Israel (Ex 12:44–48), had been accepted as members of the elect community (Jos 6:25; Ru 1:16; 4:13). The same openness is expressed in Ne 10:28–29. The repeated reference to “Israel” (12 times in Ezr 1–6) was designed to include more than just the Jews, namely, the returning exiles of those who had been deported from Judah.

7:1 Ezra. The name is a shortened form of Azariah, meaning “Yahweh has helped.” He was from a priestly lineage; his ancestors are listed back 16 generations to Aaron. One can compare the list of 1Ch 6:3–15, where 23 high priests are listed from Aaron to the exile.

7:6 teacher. The Hebrew word is the common word for “scribe.” See the articles “Literacy,” “Books and Literacy.”

7:12–26 The style of the Aramaic document recording the commission given to Ezra by Artaxerxes I bears every indication of an official document.

7:22 a hundred talents of silver. A talent weighed about 75 pounds (34 kilograms), so 100 talents was an enormous sum—about 3.75 tons (3.4 metric tons) of silver. a hundred cors of wheat. A “cor” was a donkey load, about six bushels (220 liters). The 100 cors of wheat was 600 bushels (22,000 liters), equal to 18 tons (16 metric tons). The grain would be used in meal offerings. a hundred baths of wine. A “bath” was a liquid measure of about 6 gallons (22 liters). The 100 baths of wine was about 600 gallons (2,200 liters) of wine. a hundred baths of olive oil. About 600 gallons (2,200 liters) of olive oil. salt without limit. Lit. “salt without prescribing (how much).”

7:24 Priests and other temple personnel were often given exemptions from enforced labor or taxes. An important letter of Darius to Gadates, the Persian governor in Ionia (modern western Turkey), rebuked him for disregarding his orders concerning the collection of “tribute” from cultic personnel of Apollo at Aulai.

7:26 punished by death, banishment, confiscation of property, or imprisonment. The extensive powers given to Ezra are striking and extend to secular realms. Some suggest the implementation of these provisions may have involved Ezra in much traveling, which would explain the silence about Ezra’s activities between 458 and 445 BC. Though some have questioned the wide authority given to Ezra, extra-Biblical parallels show that it was Persian policy to encourage both moral and religious authority that would enhance public order. An outstanding parallel to the king’s commissioning of Ezra is found in a similar commission of Darius I to Udjahorresnet, an Egyptian priest, scholar and military leader, who had also served under Cambyses.

8:17 Kasiphia. May be related to the word for “silver” (Aramaic kaspam) and may have been named after a guild of silversmiths. The NIV has left untranslated the word hammaqom (“the place”), which occurs twice after “Kasiphia” in this verse. As this word is sometimes used for the temple (Dt 12:5; 1Ki 8:29), some have wondered if the Babylonian exiles had a sanctuary, similar to that attested for the Jewish community in Elephantine, Egypt.

8:28 consecrated to the LORD. Both people and objects could be considered sacred, consecrated to God. Ezra carefully weighed out the treasures and entrusted them to others (vv. 29–30). He instilled a sense of the holiness of the mission and the gravity of each individual’s responsibility. Each was responsible to guard his deposit. The data were carefully recorded and rechecked at the journey’s end (v. 34).

9:1 neighboring peoples. The “peoples of the lands” included the pagan newcomers brought into Samaria by the Assyrians, as well as Edomites and others who had encroached on former Judahite territories. The eight groups listed designate the original inhabitants of Canaan before the Hebrew conquest (cf. Ex 3:8, 17; 13:5; 23:23, 28; Dt 7:1; 20:17; Jos 3:10; 9:1; 12:8; Jdg 3:5; 1Ki 9:20). Only the Ammonites, Moabites and Egyptians were still extant in the postexilic period (cf. 2Ch 8:7; Ne 9:8). Canaanites. See note on Dt 1:7; see also the article “The Canaanites.” Hittites. See notes on Ge 23:3; Dt 7:1. Perizzites. See note on Dt 7:1. Jebusites. See notes on Nu 13:29; Dt 7:1. Ammonites. See notes on Ge 19:37–38; Dt 2:19. Moabites. See notes on Ge 19:37–38; Dt 2:9; see also the article “Moab.” Amorites. See note on Nu 13:29.

10:8 within three days. As the territory of Judah had been much reduced, all could travel to Jerusalem “within three days.” The borders were Bethel in the north, Beersheba in the south, Jericho in the east and Ono in the west—about 35 miles (56 kilometers) north to south and 25 miles (40 kilometers) east to west. would forfeit. From Hebrew hrm, it means to ban from profane use and to devote either to destruction (e.g., Ex 22:20; Dt 13:13–17) or for use in the temple (e.g., 1 Esdras 9:4; cf. Lev 27:28–29; Jos 6:18–19; 7:1–26). This verse, which is the earliest attestation of excommunication, is probably a modification of the more ancient capital punishment: to be “cut off” from Israel (see notes on Lev 7:20; Nu 15:30).

10:9 ninth month. Kislev (November–December); it is in the middle of the rainy season, which begins with light showers in October and lasts to mid-April. rain. The Hebrew (using a plural of intensity) indicates heavy torrential rains.