Annotations for Daniel

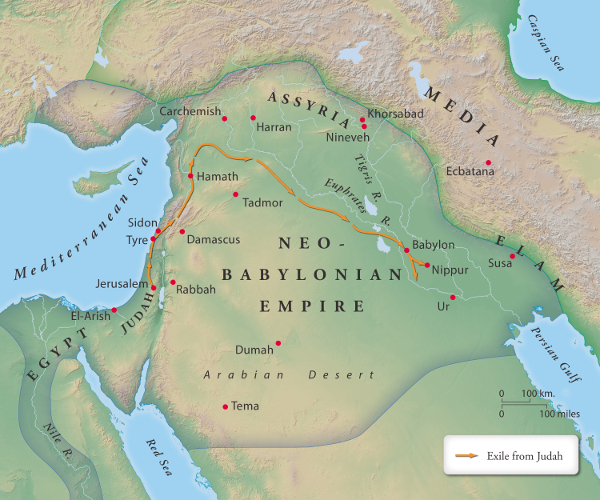

1:1 Jehoiakim. A king of Judah, he was a son of Josiah who was put on the throne by the Egyptian pharaoh Necho as he attempted to exercise control over Syria-Palestine. When Josiah was killed in battle, the people had enthroned his son Jehoahaz, who represented an anti-Egyptian faction. This situation lasted for three months (while Necho was busy at Harran). Then Necho deposed Jehoahaz and sent him off as a captive to Egypt. Pro-Egyptian Jehoiakim was then placed on the throne with the expectation that he would be a loyal Egyptian vassal. The situation changed dramatically when Nebuchadnezzar gained control of the region following the fall of Carchemish. Jehoiakim played the role of reluctant Babylonian vassal for several years, but after Nebuchadnezzar’s failure to invade Egypt in 601 BC, Jehoiakim again broke with Babylon and sought the support of Egypt in his rebellion. This disloyalty eventually proved fatal and led to the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in 597 BC (see notes on 2Ki 24:1, 10). Nebuchadnezzar. Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BC) was the second ruler of the Chaldean kingdom centered at Babylon that ruled the ancient Near East for nearly a century. He was the son of Nabopolassar, a Chaldean who declared independence from Assyria in 626 BC. In his long reign of 43 years, Nebuchadnezzar pacified Egypt (though he was unsuccessful in conquering it) and literally rebuilt the city of Babylon, which had suffered destruction at the hands of the Assyrians. In fact, most of the city of Babylon that has been uncovered by modern excavators was from Nebuchadnezzar’s reign. Thus, the Chaldean kingdom was primarily his creation, and it crumbled only a generation after his death. This great king was remembered in many cultural traditions, including sources from Greece (who knew him as a great builder) and Israel.

1:2 articles from the temple. They were made of valuable metals and therefore were desirable plunder. There was also symbolic value in taking them. For most people in the ancient Near East, taking these articles would have demonstrated the superiority of the gods of Babylonia over the God of Israel. Plundering the temple showed that the god of that temple was weak. the temple of his god. The patron deity of Babylon and head of its pantheon was Marduk. He was the son of Enki, one of the ancient triad of Mesopotamian gods. The Babylonian creation epic Enuma Elish recounts how Marduk gained supremacy in the pantheon after defeating the monsters of chaos and creating the world. This myth was formulated to legitimate the elevation of Marduk to his supreme position sometime during the second millennium BC. Nabopolassar was a devotee of Nabu, Marduk’s son, as the naming of Nabopolassar’s son Nebuchadnezzar indicates. Nebuchadnezzar seems to have made Marduk his personal god since most of his inscriptions invoke him. Nebuchadnezzar, continuing work begun by Nabopolassar, restored the ancient ziggurat, or stepped temple-tower, of Babylon, named Etemenanki (“the building which is the foundation of heaven and earth”) and the associated temple of Marduk, called Esagila (“the temple that raises its head”). These buildings dominated the city, with the temple-tower rising to about 300 feet (90 meters).

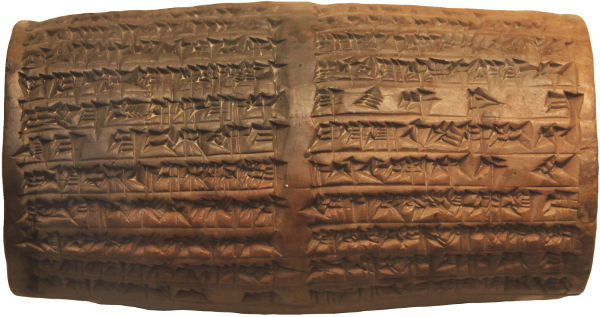

1:4 serve in the king’s palace. The training the young men were scheduled to receive was intended to prepare them for royal service. As courtiers, they might serve as scribes, advisors, sages, diplomats, provincial governors or attendants to members of the royal household, just to name a few possibilities. In seventh-century BC letters to Assyrian kings, the five principal classes of scholarly experts serving the king were: astrologer/scribe, diviner, exorcist (this term is used to describe those compared to Daniel and his friends in v. 20), physician, and chanter of lamentations. It would not be unusual for an individual to be trained in a number of these disciplines. Training foreigners for these positions was expected to result in the assimilation of the best and brightest of the next generation. Their skills would then benefit the Babylonians rather than the enemies of the Babylonians. the language and literature of the Babylonians. Babylonian and Assyrian are dialects of Akkadian, a Semitic language like Aramaic and Hebrew. While the language itself would not have been unusually difficult to learn, the system used to write it was. It required learning hundreds of symbols and the rules for using them correctly. This was done by first copying simple exercises set by the teacher. As the student progressed, he would move on to copying important literary texts. Many of these were religious in nature. The learning process was therefore also an induction into the worldview and culture of Babylonia. Though the use of wax-covered wooden writing boards was common as a temporary medium, the standard writing material in Mesopotamia was a tablet of clay, which was readily available. When moist these tablets were written on using a stylus, which was usually cut from a reed; the tablets were then dried in the sun. The stylus made wedge-shaped marks. Modern scholars call this writing “cuneiform,” from the Latin word for a wedge (cuneus). Several wedge-shaped marks were combined to form a specific “sign.” The writing system was not alphabetic, like that used to write English, Hebrew or Aramaic, but was syllabic. A syllable is a combination of a vowel and consonant(s), such as “ud,” “du,” or “dug.” Because of the number of possible combinations, a syllabic writing system needs many more signs than the number of letters used for an alphabet. About 600 distinct cuneiform signs are known. The syllabic signs used to write Akkadian were originally designed by the Sumerians to record their language. The Sumerians lived in southern Babylonia before the Semitic people who spoke Akkadian migrated into the region. Sumerian is not a Semitic language and is quite different in nature from Akkadian. As a result, the system was not ideal for writing Akkadian. This contributed to its complexity when used to write it. Babylonians. The Hebrew word used here (kasdim) is translated “Chaldeans.” Outside of Daniel it is used in the OT of the people of Babylonia in general. Chaldea appears in Assyrian inscriptions from the ninth century BC on as the name of a region in southern Babylonia inhabited by several interrelated tribes. Both Biblical and classical sources call Nabopolassar’s dynasty “Chaldean,” but there is no clear evidence that they were ethnically Chaldean. The term “Chaldean” has ethnic connotations in 5:30; 9:1; and it may here as well. In every other occurrence in Daniel, it denotes a “professional” group among the wise men. Elsewhere this meaning is first found in Herodotus in the fifth century BC, where the Chaldeans are priests of the god Bel. By Hellenistic times the term “Chaldean” came to mean specifically “astrologer.” If the term has its professional meaning here in Daniel, it may imply that Daniel and his companions were trained specifically in the literature used by diviners.

1:5 food. The Hebrew (pat-bag) is borrowed from Persian. It does not signify any particular kind of food. It was often barley and oil, and sometimes meat. from the king’s table. Many people were assigned daily rations from the king’s table: courtiers, officials, artisans, foreign dignitaries—basically those who were considered to be in some way part of the king’s household. Those receiving such rations were expected to show loyalty to the king in return. A group of tablets excavated in the southern palace at Babylon show that King Jehoiachin of Judah and his five sons received rations of oil from the royal stores. These tablets cover the years from 592/1–569/8 BC. When Nebuchadnezzar besieged Jerusalem, Jehoiachin submitted to him, and he, his family and various others of his household were taken as captives to Babylon (2Ki 24:12). trained for three years. This seems to have been the usual length of training for a competent scribe. In the literature available from the Old Babylonian period, training included the language and literature areas mentioned in the note on v. 4 as well as mathematics and music. For a diviner, it is expected that the training period was longer, but precise indications in the literature are lacking.

1:7 new names. Changing someone’s name was one way in which a conqueror expressed his authority. When Nebuchadnezzar made Mattaniah, Jehoiachin’s uncle, king in his place, Nebuchadnezzar changed Mattaniah’s name to Zedekiah (2Ki 24:17). Pharaoh Necho behaved similarly (2Ki 23:34). In both cases the new names were Hebrew names. The fact that Daniel and his companions are given Babylonian names is another indication of the intention that they should be assimilated into Babylonian culture.

1:8 defile himself with the royal food and wine. There have been extensive discussions and a variety of suggestions regarding the reasons why Daniel and his friends refused the king’s food. Most work on the assumption that the contrast is between meat and vegetables (see notes on vv. 5, 12). Others have noted that Daniel’s decision may be based on his reluctance to show allegiance to the king by sharing his food, but that would hold no matter what the young men ate. Others believe that it has to do with Jewish dietary laws (kosher), which would likely have rendered certain meat unclean. But improper storage or preparation could render other food unclean as well. Furthermore, the Jewish dietary laws did not prohibit wine. Another approach suggests the problem is with meat offered to idols. The finest meats were undoubtedly supplied to the palace from the temples, where the meat had been offered before idols (and the wine poured out in libations before the gods), but any food could easily have come through the same route. The decision certainly has nothing to do with vegetarianism or avoidance of rich foods for nutritional purposes (see 10:3). There are numerous examples in intertestamental literature (e.g., Tobit, Judith, Jubilees) of Jews seeing the necessity of refraining from food served by Gentiles. It is not so much something in the food that defiles as much as it is the total program of assimilation. At this point the Babylonian government is exercising control over every aspect of their lives. They have little means to resist the forces of assimilation that are controlling them. They seize on one of the few areas in which they can still exercise choice as an opportunity to preserve their distinct identity.

1:12 vegetables. The Hebrew word generally refers to the seeds used for animal feed, fodder or planting. In neither Akkadian nor Hebrew is it used to describe human food. But the text does not suggest that they are being provided with a restaurant-style prepared and served meal. To eat “from the king’s table” (v. 5) meant only that they were provided rations at the expense of the royal budget. It is well known that military rations consisted of measured amounts of grain that the soldiers then used to prepare their meals. Cereal grains could be ground, mashed and cooked in water to produce a porridge. This could therefore involve the same amount of ration as referred to in v. 5 but prepared by themselves rather than in the king’s kitchens.

1:17 visions and dreams. It is not always easy to distinguish between visions and dreams. Ecstatic experience, like that of the Hebrew prophets, including visions and auditions (hearing a divine voice), had only a marginal place in Mesopotamian religion. Dreams had a significant, though secondary, role in Mesopotamian divination. There were specialist diviners trained in interpreting dreams, which were considered to be communications from the gods. This verse and v. 20 suggest that Daniel and his companions were trained specifically in the literature and skills of the Mesopotamian diviners. The Mesopotamians believed that the gods communicated messages to them in various ways. It was the diviner’s task to obtain and interpret these messages or omens. The different forms of divinatory practice can be roughly divided into three types: (1) The study of unsolicited omens. This involved observing various forms of natural phenomena, such as astronomical and meteorological events, the behavior of animals, and abnormal births. (2) The obtaining of omens by using various techniques for asking a question of the god(s) and obtaining an answer. Some of the techniques used were dropping oil on water and observing the shapes formed, burning incense and observing the shapes made by the smoke, and sacrificing an animal and observing its entrails, especially the liver. (3) The use of human “mediums.” Prophecy was not common in Mesopotamia, being attested mainly from its western fringes, such as at Mari. Dream interpretation was more widespread. Necromancy (i.e., consultation of the dead by means of a human medium) was also practiced.

From the second millennium BC on a considerable amount of Akkadian literature developed around omens. Collections of different types of omens were made. Instruction manuals were written. Diviners’ reports were recorded. Various rituals and prayers related to divination were written down. Different forms of divination were popular at various times and places. In the first millennium BC the study of animal entrails, abnormal births, and astronomical phenomena (the origins of modern astrology) were particularly popular.

1:20 magicians. The term used here is of Egyptian origin (Ge 41:8, 24; Ex 7:11, 22). Egyptians were considered particularly skilled at dream interpretation, and Egyptian interpreters were employed at the Assyrian court. The term could, no doubt, be applied to all dream interpreters, whatever their ethnic origin. enchanters. The term used here is of Akkadian origin and refers to “incantation priests.” Their general task was to ward off the effects of threatening omens by performing the appropriate rituals. This often included reciting incantations. One specialty of these priests was “health care” in the sense of observing a sick person’s symptoms and other relevant factors (such as the time when the symptom occurred) and then deciding on the likely outcome of the illness and the appropriate ritual(s) to perform to deal with it. Maybe the use of “magicians” and “enchanters” makes the point that Daniel and his companions surpassed both the foreign and native wise men at the court.

1:21 first year of King Cyrus. Presumably this refers to the first year of Cyrus’s reign over Babylon, which began in October 539 BC.

2:1 second year of his reign. Nebuchadnezzar came to the throne in September 605 BC. Under the Babylonian “accession year” dating, his first year began in spring 604, and his second year ran from spring 603 to spring 602. The Babylonian Chronicle for this year is badly broken, but refers to some significant military activity. Nebuchadnezzar had dreams. In the ancient Near East dreams were considered one of the ways in which the gods communicated with humans. Since kings were believed to stand in a special relationship to the gods, their dreams were of particular importance. Several reports of dreams are found in royal inscriptions from Egypt and Mesopotamia. Nebuchadnezzar’s dream is an example of a symbolic dream, the meaning of which is not obvious and needs to be interpreted. Until this was done, he would not know whether it foretold good or ill. Dreams played only a secondary role in Mesopotamian divination. They were more important in the reigns of some kings than others, perhaps a reflection of the king’s personal piety. Dreams were thought to be messages from the gods brought by a spirit messenger whose Akkadian name was Zaqiqu. Basically two types of dream were recognized as communications from the gods. In message dreams a divine being spoke directly to the dreamer, so that interpretation was not needed. A symbolic dream involved the dreamer seeing or experiencing something, the meaning of which was not obvious; thus, interpretation was needed. All known records of this kind of dream come from Sumerian or Babylonian sources rather than from Assyrian ones. Interpretation could be done in one of two ways. Deductive interpretation relied on consultation of collections of dream omens (called “dream books”), which contained lists of things that might occur in dreams and assigned meanings to each one. Intuitive interpretation depended simply on the wisdom and insight of the interpreter. There is no evidence of a specific group of professionals who devoted themselves wholly to dream interpretation. Instead, this was done by priests, both male and female, who were competent in several types of divination. When a dream presaged something bad, there were rituals that could be performed to prevent the calamity from happening. This is one reason why it was important to discover the meaning of a dream as soon as possible.

2:2 magicians. See note on 1:20. enchanters. See note on 1:20. sorcerers. Practitioners who are condemned a number of times in the OT (Ex 22:18; Dt 18:10; Mal 3:5). The Hebrew word for them is closely related to an Akkadian term for people skilled in charms and incantations, some of which would have been used to avert the calamity presaged in a dream. astrologers. This same Hebrew term is translated “Babylonians” in 1:4. The fact that slightly different lists of “experts” are given in vv. 10, 27 indicates that the lists are simply meant to represent the range of such people at the court, not name all of them.

2:4 answered the king. At this point and continuing through the end of ch. 7, the language of the book of Daniel changes from Hebrew to Aramaic (see NIV text note). Aramaic was the international language used throughout the multilingual Babylonian Empire and beyond. Hebrew and Aramaic belong to the Semitic language family and use the same alphabet. They look much the same when written down.

2:5 I will have you cut into pieces and your houses turned into piles of rubble. Dismembering people as a punishment is attested in ancient Mesopotamia. Compare this threat with that of Darius in Ezr 6:11.

2:6 tell me the dream and explain it. A dream was thought to have its effect whether or not the dreamer could remember its details on waking. To forget a dream was itself a bad omen, indicating the anger of the dreamer’s personal god. Nebuchadnezzar may have forgotten the details of his dream, but it is also possible that he was testing his diviners to try to ensure a genuine interpretation of what he thought might be a particularly important dream. Kings did not always trust their “experts.” On at least one occasion Sennacherib separated diviners into groups to reduce collusion and ensure a reliable interpretation of an omen.

2:11 What the king asks is too difficult. It was part of the diviner’s art to interpret dreams by either deductive or inductive means (see note on v. 1), but the diviner had no means for discovering what the dream itself had been. It was believed that the gods communicated through dreams, and the experts believed that the gods would reveal to them the interpretation of the dreams through their use of the resources available to them. There was no precedent for the gods revealing the dream itself.

2:12 he ordered the execution of all the wise men. There are partial parallels to this angry outburst and threat by Nebuchadnezzar in Saul’s massacre of the priests at Nob (1Sa 22:13–19) because they had helped David. In secular history, a parallel exists in Darius’s massacre of the Magi because one of them had usurped the throne. A closer parallel is Xerxes’ beheading of the engineers who built a bridge that was destroyed in a storm, since it was a case of punishing failed “experts.”

2:14 commander of the king’s guard. This is the official title of an important functionary whose duties were sometimes unsavory. When Jerusalem fell to the Babylonians, the commander in charge of methodically destroying and dismantling the city and disposing of captives either by execution or deportation carried this title (2Ki 25:8). It is similar to the title held by Potiphar in Ge 37:36. The terminology suggests something like “chief cook,” but like some of our contemporary government titles (e.g., “party whip”), the office must be understood by examining its function, not its title.

2:18 the God of heaven. This title for God is found in Ge 24:3, 7. Its other uses in the OT are in postexilic books, especially Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah. Persian documents use it of Ahura Mazda, the good god of Zoroastrianism (see the article “Zoroastrianism”). It is used to refer to the God of Israel in the papyri written by the Jewish colonists at Elephantine in Egypt. Clearly it was an epithet for God that was acceptable to both Jews and non-Jews.

2:27 wise man. In Daniel this is a general term for an expert in various forms of divination. This “mantic wisdom” is different from the “instructional wisdom” of “the wise” spoken of in the book of Proverbs (e.g., Pr 1:5; 3:35; 9:9). enchanter. See note on 1:20. magician. See note on 1:20. diviner. This term comes from a verb that means “to cut,” hence “to determine.” It may mean “fate determiner”—i.e., a person who foretells someone’s fate. The use of the word in the Qumran scrolls, however, suggests the meaning “exorcist.”

2:31 a large statue. The appearance of colossal figures, often the statue of a deity, is fairly common in dream reports from the ancient Near East. Pharaoh Merneptah saw a giant statue of the god Ptah, who gave Merneptah permission to fight the Libyans. The Sumerian ruler Gudea saw a huge figure in a dream. In one dream reported in the reign of the Assyrian emperor Ashurbanipal, an inscription on the pedestal of a statue of the god Sin foretold the failure of a rebellion. Apparently it was not only rulers who had such dreams. One of the motifs listed in the Babylonian “dream book” is the appearance of a god’s statue. What Nebuchadnezzar sees in his dream differs from these in that the figure represents the course of history.

2:32 The head of the statue was made of pure gold. No major statues of gods from first-millennium BC Mesopotamia have yet been discovered. A number of divine images from the second millennium BC have been recovered, and some are made of a combination of materials. One example from Ugarit is a bronze figure of a god, the head of which was covered with gold and the body with silver. Another is made from five materials: electrum, gold, silver, bronze and steatite. King Esarhaddon of Assyria boasts of a statue of himself made of gold, silver and copper that was placed before the gods to constantly request well-being for him. Since idols were often “dressed,” it is possible that it was the parts that were visible that were covered with precious metals (or perhaps the metals were used in crafting the clothing of the statue).

2:33 its feet partly of iron and partly of baked clay. It is not clear what this means. It has been suggested that the reference is to iron inlaid with terra cotta.

2:40 Finally, there will be a fourth kingdom. The division of a period of history into four empires or four ages, sometimes symbolized by four metals, has a number of parallels in ancient and classical literature. Two Zoroastrian texts speak of four ages symbolized by four metals: gold, silver, steel and “iron mixed” (the exact meaning of this is unclear). These texts are known only from thirteenth-century AD copies, but the material in them is much older. It is unlikely to be any older than the third century BC because the rulers of the final age seem to be Alexander the Great and his successors. A portion of Sibylline Oracle 4, which probably dates to the third century BC, speaks of four world empires: Assyrian, Median, Persian and Macedonian. These empires are not linked with any metals. A later addition adds Rome as a fifth empire. The sequence of empires reflects the experience of that part of the eastern Mediterranean world, perhaps part of Asia Minor, that passed directly from Assyrian rule to Median rule. In his Works and Days the eighth-century BC Greek poet Hesiod divides history into five eras. Four are characterized by metals in the sequence gold, silver, bronze and iron. Between the bronze and iron eras, Hesiod inserts the era of the Greek heroes, but he does not link it to any metal. This sequence of metals seems to rest on the historical memory of the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, since of the era symbolized by bronze the poet says, “Of bronze were their implements: there was no black iron.” The Latin poet Ovid adopted this four-metal scheme, without the era of heroes, in his Metamorphoses (late first century BC). Hesiod’s scheme seems to have been well known throughout the eastern Mediterranean world. It may be reflected in the imagery of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, which follows it with the addition of the admixture of clay with iron in the feet. Nebuchadnezzar, probably representing the whole Babylonian Empire, is identified with the head of gold. Identification of the rest of the sequence depends on evidence drawn from Da 7–8.

2:44 but it will itself endure forever. A Babylonian text known as the Uruk Prophecy describes the rise and fall of a series of kings. Concerning the last king mentioned it says not only that he will rule in Uruk but that his dynasty will be established forever. According to one possible interpretation of the text, this king is Nebuchadnezzar. This statement seems to turn into prophecy what is sometimes requested in royal prayers. Nabonidus, e.g., prays that his dynasty would be established forever.

2:46 presented. This verb usually is used in Hebrew for pouring out libations. But neither the (grain) offering nor the incense that are mentioned here can be poured out in libations. The text here, however, continues to be in Aramaic, in which the verb means “provided.” This makes Nebuchadnezzar’s treatment of Daniel a bit more understandable, as he provides Daniel with the materials with which Daniel can make an appropriate offering to his God.

2:48 ruler over the entire province of Babylon. The empire was divided into provinces, or satrapies, of which Babylon was one. Daniel is exalted to high office in the province, but that vague description finds definition in the next statement that clarifies the nature of this high office: he is made prefect over the wise men. This is more likely a ranking within his guild rather than an administrative position in the civil government.

3:1 an image. The image is never positively identified as the image of a deity, though v. 28 could easily suggest it. If the image was a divine image, it would be odd that the name of the deity was not given and even more unusual that it was set up in an open area rather than associated with a temple. Part of the care of the gods was to house and feed them, and such maintenance could not easily be kept up in an open location. If it is not the image of a god, it becomes more difficult to understand the three friends’ refusal to participate in its service or worship (v. 28; see note on Ex 20:4). The other main alternative is to see it as an image of the king. But there was no prohibition against bowing down before kings as an act of respect. Additionally, images of kings during the Assyrian and Babylonian periods were usually made to be put in temples to stand before the deity requesting the well-being of the king. Typically, then, they represented the king to the god, not to the people. Perhaps the best alternative is to understand the event in the context of the Assyrian practice of erecting steles or statues (often in inaccessible places) that commemorate a king’s rule. While these were intended to exalt the king, the reliefs on the Balawat gates demonstrate that offerings were made before these representations. In the scene portrayed on the gates, the king himself is present, but the offerings are made to the stele. In this way the king is given the honors that are generally given to the gods, but by personally distancing himself, he does not make himself equal to the gods. Such rituals were used as occasions for provincial territories to take loyalty oaths. This would make sense here in light of the suggestion in the dream of ch. 2 that the Babylonian kingdom would have a limited time of rule. In Assyrian practice, the weapon of Ashur (perhaps even a battle standard) was set up for ceremonies in which vassal kings entered into loyalty oaths. Failure to participate would suggest insubordination, whereas participation would signify the acceptance of the deity’s (and king’s) sovereignty. The three friends are not being asked to worship a deity, but they are being asked to participate in rituals that honor the king in ways similar to how the gods were treated (though the king is not being viewed as deity). Their interpretation causes them to consider this bowing down to be forbidden by their law, and they feel strongly enough about that that they are willing to risk their lives. sixty cubits high and six cubits wide. That is, about 90 feet (27.5 meters) high and 9 feet (2.75 meters) wide. These proportions are odd since the height to width ratio for a normal human figure is about five to one. It may be that part of the height was a pedestal, though one would expect the pedestal to be wider than the image in order to provide the structure with stability. Another possibility is that it was a partially sculptured stele. Although such a stele would not normally be described as an “image,” there is an example of the Aramaic word used here being used of such a stele. Dura. The Akkadian word dûru means “a walled place.” Several towns were named Der, and “Dur-” was a common element in place-names, making it impossible to locate the “plain of Dura” with any certainty.

3:2 summoned. As mentioned in the note on v. 1, it is likely that the occasion for this gathering was for the taking of a loyalty oath. A century earlier it is known that Assyrian king Ashurbanipal gathered his chief officials together in Babylon to take a loyalty oath. A letter has been preserved from one of the officials who was out of town and therefore made arrangements to take the oath in the presence of the palace overseer. The letter specifically mentions that when he took the oath he was surrounded by the images of the gods. satraps. A Persian term borrowed into Aramaic as early as the sixth century BC for the ruler of a province. prefects, governors. Both are Semitic titles for the two levels of subordinates to the satraps. advisors, treasurers, judges, magistrates. These are Persian loanwords whose translation is very tentative. The list of officials appears to be in rank order.

3:5 The names of several of these instruments are Greek, but there had been enough contact with Greece even by the sixth century BC that this is not unusual. Nebuchadnezzar was known to make use of foreign musicians, as shown in the rations lists. These lists also attest to the presence of some Greeks in Babylon. horn. A wind instrument that, judging by the word used, is an animal’s horn rather than a metal trumpet. flute. A wind instrument of the variety that is played by blowing through the end. zither. A stringed instrument whose name is borrowed from Greek. It is known from Homer’s writings (eighth century BC) and is a type of lyre. There were a wide variety of lyres in the ancient world, but there are no early attestations of the zither or dulcimer. lyre. A stringed instrument whose name occurs as a foreign word in Greek. It is probably a harp. harp. A stringed instrument that is most likely a different style of lyre. pipe. This is the most difficult of the instruments to identify. Suggestions have ranged from bagpipes to double flute to percussion. It is a Greek loanword into Aramaic, and it happens also to come into English as “symphony.”

3:6 thrown into a blazing furnace. Death by burning is referred to occasionally during the Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian and Greek Empires. Most notably, a letter from a Mesopotamian king dating to the sixth century BC instructs a governor to throw corrupt priests into a burning oven. No clear details are given about the furnace. Verses 22–23 may indicate that it had an opening at the top through which the victims were thrown into the fire, and there seems to have been a door or opening in the side through which Nebuchadnezzar could see into it (v. 25). It was probably constructed not for the purpose of punishment but for the making of the image, which would have required melting and casting the metal, or for other construction work.

3:19 seven times hotter. This is hyperbole. The brick kilns of the time normally operated at around 1650°F (900°C). With the technology available it would not have been possible even to double this temperature.

3:25 a son of the gods. This is a common expression in Semitic languages for a supernatural being. A polytheist like Nebuchadnezzar would use it for a member of the pantheon of gods. Recognition of a figure as divine would normally be predicated on either the clothing (especially a horned helmet) or what the Babylonians referred to as a melammu, a divine glow around the being.

4:1–2 A proclamation such as this would typically be recorded on a stele and set up in a prominent place. Sometimes copies would be made and circulated around, such as was done with Darius’s Behistun inscription. Many of the elements of this proclamation are common to royal inscriptions or to Aramaic letters, though it is unusual for a king to be so vulnerable as here.

4:1 King Nebuchadnezzar, To the nations and peoples of every language. This form of opening is common in Aramaic letters of the Persian period and is also found in Neo-Babylonian letters. A Biblical example is Ezr 7:12. May you prosper greatly! The great majority of Aramaic letters follow the opening with a greeting involving some form of the Aramaic root shlm (“peace, well-being, prosperity”), as here.

4:4 I, Nebuchadnezzar. The use of “I” and the content of what follows give what began as a letter similarity to two other forms of Akkadian literature. The first is the fictional Akkadian autobiography (an example is the “Cuthean Legend of Naram-Sin”). This also tells of a king’s act of pride (failing to heed the gods’ instructions given through omens) that leads to disaster and repentance. It was published for the benefit of others—in the case of Naram-Sin, other kings. The other form of literature is the dream report (see notes on 1:17; 2:1).

4:10–12 The concept of the cosmic tree in the center of the world is a common motif in the ancient Near East. It is also used in Eze 31 (see note on Eze 31:3–14). Its roots are fed by the great subterranean ocean and its top merges with the clouds, and thus binds together the heavens, the earth, and the netherworld. In the Mesopotamian epic “Erra and Ishum,” Marduk speaks of the meshu tree whose roots reach down through the oceans to the netherworld and whose top is above the heavens. In the Sumerian epic Lugalbanda and Enmerkar, the “eagle-tree” has a similar role. In Assyrian contexts, the motif of a sacred tree is also well known. Some have called it a tree of life, and some also associate it with this world tree. It is often flanked by animals or by human or divine figures. A winged disk is typically centrally located over the top of the tree. The king is represented as the human personification of this tree. The tree is thought to represent the divine world order, but textual discussion of it is lacking.

4:13 messenger. The Aramaic noun used here means “one who is awake, a watcher.” The “Watchers” are widely attested in Jewish literature of the Hellenistic and early Roman period. The best-known example is “The Book of Watchers” in 1 Enoch 1–36, where the term usually refers to the fallen angels. However, even in 1 Enoch the term is used of the (good) archangel Raphael (1 Enoch 22:6) and of the four archangels (1 Enoch 20:1). There is no evidence outside Daniel of the word “watcher” being used in this specialized way of heavenly beings before the third century BC, though Mesopotamian religion included the idea of a variety of protecting deities or angels.

4:15 the stump and its roots, bound with iron and bronze. It is difficult to determine whether it is a part of the tree that is bound with iron, or whether it is the king. If it is the tree, the text indicates that its taproot should be bound (not the stump). While trees are sometimes gilded with metal bands in ancient Mesopotamia, there is no case of treating a stump that way, much less a taproot. dew of heaven. In Babylonian texts, dew is considered to come down from the stars of heaven and is sometimes seen as the mechanism by which the stars bring either sickness or healing.

4:16 Let his mind be changed. See note on v. 33. seven times. This may mean seven years, but there is no firm basis for this. The word for “times” means a definite period, though one that can be of any length. Omens sometimes had a set time over which their effects could take place, which could be of various lengths.

4:22 Your Majesty, you are that tree! The ancient Near Eastern king was sometimes identified with the tree of life (see note on vv. 10–12), as he was the source of protection and sustenance for his people. Also, there are what seem to be anthropomorphic depictions of the Assyrian sacred tree, thus drawing together the cosmic tree of the dream with the king’s identification as the tree.

4:30 the great Babylon I have built. Nebuchadnezzar carried out major building works in Babylon. The Euphrates was channeled into a number of canals passing through the city. He embellished the major streets, especially the great Procession Way along which the images of the gods were drawn at festivals. Moreover, he did major work on the religious buildings of the city (see note on 1:2). According to later historians, he built a luxurious palace with its hanging (terraced) gardens, which was identified as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, though recent studies by scholars have suggested that it was actually Sennacherib’s building in Nineveh that was mistaken as Nebuchadnezzar’s in Babylon. Regardless, his building activity was extensive and legendary.

4:33 What is said about Nebuchadnezzar’s condition here and in v. 16 is often identified by modern interpreters as zooanthropy, a psychological disorder in which a person thinks they have become an animal and behave accordingly. An alternative sees the change that happened to Nebuchadnezzar as that which is also described as happening to the hero in the Tale of Ahiqar: “The hair on my head had grown to my shoulders, and my beard reached my breast; and my body was fouled with dust and my nails were grown like eagles.” There are also parallels with what is said of the wild, animal-like creature Enkidu in the Gilgamesh Epic who is described as hairy, unclothed and eating grass before he became “civilized” as a human being. It is therefore possible that the description of Nebuchadnezzar is intended to present him as an exile from civilized human society. Very few surviving Babylonian sources give information about the last 30 years of Nebuchadnezzar’s life. A fragmentary cuneiform text seems to refer to some mental disorder afflicting Nebuchadnezzar and perhaps his neglecting and leaving Babylon, maybe putting his son Amel-Marduk (Biblical Awel-Marduk) in charge for a while, and then of his repentance for neglect of the worship of the gods. Unfortunately the text is too fragmentary for any firm conclusions to be drawn.

5:1 King Belshazzar. The son of Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon. He acted as regent in Babylon while Nabonidus spent ten years in Tema in Arabia. Because Belshazzar did not enjoy full royal prerogatives and was not given the title “king” in Babylonian records, it has been argued that calling him “king” here is inaccurate. A bilingual ninth-century BC inscription throws light on this issue. In the Assyrian text the ruler of Guzan is called “governor,” whereas in the Aramaic text he is styled “king.” This suggests that the Aramaic term “king” (mlk) had a wider meaning or was used more loosely than the Akkadian term (sharru) and that it is not wrong to use it of Belshazzar. gave a great banquet. This story records the final downfall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in mid-October 539 BC. There are a number of accounts of the fall of Babylon (the first three in contemporary ancient Near Eastern sources, the last three in later classical sources), which differ in some details. (1) The Cyrus Cylinder says that Cyrus entered Babylon unopposed and captured Nabonidus. (2) The Babylonian Chronicle says that Nabonidus fled following a revolt against him in Babylonia and Cyrus’s capture of Sippar without a fight. He was later captured when he returned to Babylon. Cyrus entered Babylon without a battle. (3) The Dynastic Prophecy seems to say that Cyrus sent Nabonidus into exile. (4) Berossus says that Cyrus captured Babylon while Nabonidus was besieged in Borsippa. Nabonidus then surrendered and was sent into exile in Carmania. (5) Herodotus says that Cyrus captured Babylon by temporarily diverting the course of the Euphrates when the Babylonians were feasting and dancing. His troops waded along the riverbed, where the river passed through the city walls. (6) Xenophon says much the same, adding that the Persians took the city at night and that Gobryas, one of Cyrus’s generals, killed the Babylonian king, a riotous, indulgent, cruel and godless young man. The king said to have been killed by Cyrus’s general Gobryas may have been Belshazzar. banquet. This banquet is taking place in mid-October (15th of Tashritu) 539 BC. In the past few days the Persians had taken the city of Opis (50 miles [80 kilometers] north on the Tigris) in a bloody battle, and then crossed over to the Euphrates, where the city of Sippar surrendered without a fight on the 14th of Tashritu. It is likely that Babylon has received word of these events and that Belshazzar knows that the Persian army is on the march toward Babylon. Some sources indicate that Nabonidus had been with the army at Opis and fled when the city fell. When Nabonidus was captured, it was in Babylon, but the texts are unclear about when he arrived. Berossus (a third-century BC Chaldean historian, quoted by Josephus) claims that he was trapped in the city of Borsippa (about 17 miles [27 kilometers] south of Babylon). In light of all of this, it appears that the banquet represents one final gathering before the momentous events that are about to transpire. Herodotus refers to a festival celebration that was taking place when the city fell. There is no reason to think, however, that the banquet reflects Belshazzar’s pessimism about the outcome. Babylon was a defensible city, and the Babylonians believed their gods to be strong.

5:2 the gold and silver goblets . . . from the temple in Jerusalem. See note on 1:2. These goblets had probably not been melted down because they were recognized as sacred objects. In v. 23 Daniel condemns Belshazzar for putting sacred vessels to profane use and for using vessels dedicated to the Most High God to worship idols. Nebuchadnezzar his father. Belshazzar was the eldest son of Nabonidus. As early as Herodotus in the fifth century BC, Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus are given the same name in Greek (Labynetos). Daniel may be following the same tradition as Herodotus. Alternatively, Nabonidus might have married one of Nebuchadnezzar’s daughters, making Belshazzar Nebuchadnezzar’s grandson. In the Semitic languages “father” and “son” can be used of more distant forebears and descendants. Another possibility is suggested by the inscription on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III. In this artifact Jehu, a king of Israel, is called “son of Omri” even though he had no blood relationship to him. He is simply being designated as the successor to a well-known king.

5:4 praised the gods. Belshazzar and his administration are well aware that the empire hangs by a thread and that the next several days will be of utmost significance. They are hoping that their gods will bring victory for them, as they had in the days of Nebuchadnezzar’s great conquests. To that end, they are “toasting the gods” and celebrating their past victories. It is also possible, though not explicitly stated, that libations were poured out to the gods from these vessels. They are making their supplications not only to Marduk, the patron of Babylon, but to the gods of other cities of the region whose images had been gathered into Babylon during these troubled times.

5:5 a human hand. A lifeless, detached hand would have suggested a defeated enemy. Casualty counts were made by cutting off the right hands of all of the dead (recall the broken-off hands of Dagon in 1Sa 5:3–4). By drinking from the vessels, the Babylonians were recalling the defeat of Yahweh (perhaps along with other gods and nations), but this is no lifeless, severed hand of a dead god. It is quite animated and has a message to give. The effect might be similar if the head of a decapitated victim began to speak. wrote on the plaster of the wall, near the lampstand. This is a curious detail since one might have expected plaster all around the room that would be illuminated by many lampstands. The excavation of the throne room in Babylon can offer some explanation. The hall was 170 feet (51.8 meters) by 55 feet (16.75 meters); it was entered through three spacious courtyards that led the way from the entrance just inside the Ishtar Gate. Some of the wall space was covered with blue enameled brick, while other parts were plaster. The word used for lampstand is an unusual one and may be a Persian loanword. As such it likely represents a distinct, singular lampstand, perhaps of a special type.

5:7 clothed in purple and have a gold chain placed around his neck. Marks of honor and royal approval (Ge 41:42; Est 8:15). Purple clothing was made using an expensive dye and was normally only worn by royalty. The chain may have been an insignia of office. third highest ruler. This may indicate being ranked only behind Belshazzar and his father, Nabonidus—though the term used may represent the title of a high official.

5:8 they could not read the writing. Some have suggested that the writing was in code or an unusual language, but nothing in the text suggests this. Aramaic, like Hebrew, was written without vowels and sometimes without word divisions. Thus, the writing on the wall may have consisted of a string of nine consonants (mnʾtqlprs). Uncertainty about word division and vowels would be enough to baffle the wise men and leave them unable to say what it meant.

5:10 queen. That she can enter the king’s presence unbidden and that her memory goes back beyond that of Belshazzar suggests that the “queen” is the queen mother. Also, she seems to be a different person from any of Belshazzar’s wives noted in vv. 2–3. In ancient Near Eastern courts the queen mother was often an influential figure. Nabonidus’s mother (Belshazzar’s grandmother), Adad-Guppi, was a very influential person and the quintessential queen mother. Her 104 years, however, had come to a close about 546 BC, so she was no longer alive at this time. Nabonidus’s wife, Belshazzar’s mother, identified by Herodotus as Nitocris, is more likely referred to here.

5:25 MENE, MENE, TEKEL, PARSIN. Initially Daniel reads the writing as the names of standard Babylonian weights: the “mina,” the “shekel,” and the “peres” (parsin is a form meaning “two peres”). Archaeologists have found weights with these names inscribed on them. The mina was 60 times the weight of the shekel in Babylonia but 50 times the shekel in Palestine. The name “peres” often means a half mina but can mean a half shekel. Alternatively, the words can be taken as verbs for weighing and assessing. As such their significance extends beyond the commercial realm, as scales and weights were also used to depict divine evaluation and judgment (as in the Egyptian “Book of the Dead”). Daniel appears to have used both noun and verb forms in his interpretation. Wordplay was a common means used to interpret omens in this period. It also would be ironic that the last term, peres, also sounds like the word for the Persians.

5:27 weighed on the scales. The imagery of the scales may have had an astronomical connotation. Babylon fell on the 16th of the Babylonian month Teshrit. Babylonians traditionally linked this month with the constellation of The Scales (the one we call Libra). Its annual appearance in the night sky for the first time was associated with the middle of the month. The court astrologers would know this and would have seen it as confirmation of Daniel’s interpretation of the omen.

5:31 Darius the Mede. All extra-Biblical sources say that Cyrus II of Persia captured Babylon (539 BC). No historical king named Darius is known until Darius I of Persia, who ruled from 522–486 BC. There have been various suggestions identifying Darius the Mede with a known historical figure. One popular suggestion identifies Darius with Ugbaru (Gobryas in Greek), the general who captured Babylon on Cyrus’s behalf. He was governor of Gutium in Media. However, it is now clear that he died only three weeks after capturing the city, and there is no evidence that he was given the title “king,” as Darius is in Da 6:6. Another suggestion identifies Darius with a governor of Babylon and Beyond the River (the area west of the Euphrates) called Gubaru. But it is now clear that he was not appointed to this post until four years after the capture of Babylon. The most likely suggestion, though it too has problems, takes Darius the Mede as an alternative name for Cyrus the Persian, who was about 62 years old when Babylon fell (see note on 6:28).

6:1 satraps. The main administrative division of the Persian Empire was the satrapy. The number of satrapies with their ruling satraps varied with time but was usually in the 20s. Greek writers used the term “satrap” of various Persian royal officials as well as of the governors of the satrapies. This, presumably, is the case here.

6:7 edict . . . decree. The content and implications of this decree have caused much debate. There is no evidence that the Persian kings were ever inclined to deify themselves. This leads some to suggest that the decree simply made the king the sole representative of the deity for the period of 30 days. All prayers to God or the gods would need to be channeled through him. We could speculate that the king accepts such a suggestion to address the struggle in Persia between the advocates of pure Zoroastrianism (see the article “Zoroastrianism”) and the supporters of the traditional Persian religion who advocated a syncretistic form of religion, which the Magi seem to have favored. The decree could be seen as a stand against syncretism, with the king representing Ahura Mazda. Given that Persian rulers had a tolerant attitude to the religions of their subject peoples, Darius probably intended the decree to apply to the Persian population alone. Daniel fell afoul of it because he was a very senior Persian official. den. The Aramaic word used means “pit.” The pit envisaged in this story seems to be an underground cavity with a relatively small hole at the top that could be covered by a large stone. Although this particular form of punishment is not mentioned elsewhere, in earlier Assyrian texts, oath breakers were put into cages of wild animals set up in the city square to be publicly devoured, and the Persian kings used some horrible forms of execution.

6:8 the law of the Medes and Persians . . . cannot be repealed. This concept can be traced far back in literature, particularly with reference to the gods, whose decrees were unchangeable; however, no specific attestation has been documented outside of the books of Daniel and Esther (Est 1:19; 8:8). Nonetheless, a tradition at least as early as the time of Hammurapi (eighteenth century BC) recognized that a judge could not change a decision that had been made. In this sense, we may be dealing with a ruling rather than a law. Greek sources conflict with one another; Herodotus indicates significant freedom on the part of Persian kings to change their minds, while Diodorus Siculus cites an instance where Darius III could not do so. Certainly no lower official could countermand the decrees of the Persian king, and the king himself may have thought it too humiliating to go back and reconsider something he had already decreed. Royal code of honor would have made it out of the question for the king to rescind an order.

6:10 windows opened toward Jerusalem. The practice of praying facing the temple in Jerusalem is mentioned in the OT only in 1Ki 8:22–54; Ps 5:7. Three times a day. Prayer at “evening, morning and noon” is mentioned in Ps 55:17, but it is not clear whether this was a generally accepted practice. 1Ch 23:30 refers only to morning and evening prayers in the temple. down on his knees. The OT refers to both standing (1Ch 23:30; Ne 9:2, 5) and kneeling (1Ki 8:54; Ezr 9:5) in prayer. Daniel’s practice of prayer probably reflects a custom that grew up among the Jewish exiles in the eastern Diaspora.

6:17 the king sealed it with his own signet ring. There were three kinds of seals in use in the ancient Near East: cylinder seals, stamp seals and signet rings. The signet ring tended to be used for more personal business. The stone closing the pit was sealed in some way with several different seals to prevent it being tampered with in the night. Possibly a cord or cloth was fastened across the rock using clay, into which the seals were impressed.

6:19–23 This passage describes innocence by ordeal. “Ordeal” describes a judicial situation in which the accused is placed in the hand of God using some mechanism, generally one that will put the accused in jeopardy. If the deity intervenes to protect the accused from harm, the verdict is innocent. Most trials by ordeal in the ancient Near East involve dangers such as water, fire or poison. When the accused is exposed to these threats, they are in effect being assumed guilty until the deity declares otherwise by action on their behalf.

6:24 along with their wives and children. This is an unusually severe form of punishment. When a high-ranking official and close associate of Darius I was judged guilty of revolt against him, Darius had most of the man’s family executed with him. It would also be logical that the king would not want to leave family members of the executed alive to foment rebellion or conspire against him.

6:28 the reign of Darius and the reign of Cyrus. This can also be translated “the reign of Darius, that is, the reign of Cyrus” (see NIV text note). Note the similar construction in 1Ch 5:26: “Pul king of Assyria (that is, Tiglath-Pileser king of Assyria).” Kings in the ancient Near East usually had more than one “throne name.” the Persian. Since Cyrus took over the Median Empire and had a Median mother, he could also be called “the Mede,” even “king of the Medes.”

7:1 the first year of Belshazzar king of Babylon. This year is presumably the first year of Belshazzar’s regency. The “Verse Account of Nabonidus” says that when Nabonidus went to Tema, he “entrusted the kingship” to Belshazzar. According to his own inscriptions, Nabonidus spent ten years in Tema, so the first year of the regency cannot be later than 550/549 BC. The Chronicle for Nabonidus’s seventh year (549 BC) mentions Belshazzar as regent in Babylon, but the accounts of the earlier years are broken or missing, so it is not possible to say for certain when the regency began. In any case the dating means that Daniel’s vision in ch. 7 took place before the events of chs. 5–6.

7:2–3 the four winds of heaven churning up the great sea. Four great beasts . . . came up out of the sea. The phrase “the four winds (of heaven)” is common in Akkadian literature. Outside Daniel, the only occurrences in the Hebrew Bible are in Jer 49:36; Eze 37:9; Zec 2:6. All these, like Daniel, have a Babylonian connection. Jeremiah was addressing Elam at a time when it and Judah were under Babylonian rule; Ezekiel prophesied in Babylon; Zechariah was with a group of Jews who had returned from exile there. The imagery of strange monsters in a turbulent sea is reminiscent of the Babylonian creation epic Enuma Elish, in which a turbulent sea and weird monsters represent the forces of chaos. These forces, led by the goddess Tiamat (who has the form of a dragon in the story), have to be defeated by Marduk, the god of Babylon, before he can create the ordered world. Among the weapons he takes for the battle with Tiamat are the four winds.

7:3–8 In the Babylonian omen series called Shumma izbu, which Daniel would have been well aware of from his training, various birth abnormalities are recorded along with what sort of event they forecast. Several of the descriptions of the beasts in Daniel’s visions can also be found in the Shumma izbu series. Some of the common elements in the descriptions include: raised up on one side (cf. v. 5), multiple heads (cf. v. 6), and multiple horns (cf. v. 7). Most of the observations of abnormalities were made of domesticated species, a large proportion being sheep and goats. Some of the abnormalities are described by comparison to various wild beasts. There are examples of sheep giving birth to lambs that (in some way) resemble a wolf, a fox, a tiger, a lion, a bear, or a leopard. In ch. 7 Daniel is observing these abnormalities not in reality but in a dream (v. 2), thus combining two important omen mechanisms (dreams and odd births). The “dream books” (see note on 2:1) often feature ominological information (celestial or extispicy omens) being viewed in dreams and carrying the same significance as if they were viewed in reality. Being familiar with both literatures, Daniel would have been inclined to interpret the dream along the lines suggested in the izbu omens. The omen interpretations often concerned political events, e.g., “the prince will take the land of his enemy.” Nevertheless, Daniel’s dream goes well beyond the izbu omens. The descriptions suggest that he does see fearsome chaos beasts rather than simply sheep or goats with odd characteristics. Additionally, many of the features of Daniel’s beasts are neither found nor expected in izbu omens, e.g., wings and iron teeth. For this reason it is also important to understand the nature of some of the mythological imagery that pertains to the dream. A number of different mythological sources offer similarities to the beast imagery used by Daniel. A seventh-century BC Akkadian piece called “A Vision of the Netherworld” includes 15 divine beings in the forms of various hybrid beasts. Following that, Nergal, king of the netherworld, is seen seated on his throne; he identifies himself as the son of the king of the gods. There are many significant differences between this vision and Daniel’s vision, but the similarities in imagery are helpful background.

7:3 out of the sea. In the Bible and in the ancient Near East, the sea represents chaos and disorder, as do the sea monsters that live there (see the article “Chaos Monsters”).

7:4 lion . . . wings of an eagle. Winged figures are common in the art and sculpture of Mesopotamia. Winged bulls and winged lions, both with human heads, flanked thrones and entryways in Assyria, Babylon and Persia. Winged human figures (wearing headdresses with horns) are known as early as the eighth century BC and stood guard at Cyrus’s palace in Pasargadae. Winged creatures also figure in dreams. Herodotus reports a dream that Cyrus had just a few days before his death in which he saw Darius (then a young man) with wings that overshadowed Asia and Europe. In the Myth of Anzu (see next note), Anzu is defeated by having his wings plucked. This motif is also significant in the story of Etana, who helps an eagle whose wings have been plucked.

7:7 a fourth beast. In the Myth of Anzu, a composite creature (Anzu) steals the “Tablet of Destinies,” which comprised a sort of constitution of the cosmos. The goddess Mami, the most ancient of deities who created all the gods, is called forth. She is asked to send her son, Ninurta, to battle Anzu. The god Ninurta defeats the monster and recovers the “Tablet of Destinies.” Ninurta (who is also known for his defeat of other beasts, e.g., the bull-man in the sea, the six-headed ram, and the seven-headed serpent) then is granted dominion and glory. There are certainly many differences with Da 7, and there should be no thought that the Myth of Anzu figures prominently here. Those who would have been familiar with the Myth of Anzu, however, would likely have seen echoes of it in this vision. The myth has roots as early as the beginning of the second millennium BC but is principally known from mid-first-millennium Babylonian texts. One ninth-century BC relief inscription from Nimrud pictures Ninurta fighting a beast with lion’s legs but standing upright on eagle’s feet. The beast is feathered and has two wings, lion paws for hands with sharp, extended claws, a gaping mouth with fierce teeth, and two horns. It is thought to be a depiction of Anzu. ten horns. It was common in Mesopotamia for gods (and occasionally kings) to wear crowns featuring protruding or embossed horns. Sometimes the sets of horns were stacked one upon another in tiers. The winged lion from Ashurnasirpal’s palace has a conical crown on its human head with three pairs of tiered horns embossed on it. Another interesting connection is that in the creation epic Enuma Elish, Tiamat is the fearsome beast that the hero of the gods has to defeat. To help her, Tiamat creates 11 monsters that must also be defeated. Here also the fourth beast is associated with 11 horns (the ten plus the little horn).

7:9 the Ancient of Days. In Canaanite mythology the head of the pantheon is El, who is depicted as an aged person. Among his titles are “judge,” “father” and a phrase that is usually taken to mean “father of years.” This suggests that Daniel is using imagery and descriptions that would have been well known to his audience. His throne was flaming with fire, and its wheels were all ablaze. The immediate background here is probably Ezekiel’s vision of God’s fiery chariot throne (Eze 1; 10). A more general background may be the chariots or carts used to carry the images of deities in processions in the ancient Near East.

7:10 the books were opened. Record keeping of various kinds was common in ancient royal courts. There are numerous references in 1-2 Kings to “the book of the annals of the kings of Israel/Judah” (e.g., 1Ki 14:19, 29). Est 6:1 refers to “the book of the chronicles” that recorded events in the reign of the Persian king. No doubt these records were similar to the Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles. Records were also kept of royal decisions and decrees (Ezr 6:1–5).

7:13 one like a son of man. In Aramaic and Hebrew the phrase “son of man” is simply a common expression to describe someone or something as human or humanlike. In Ezekiel, God often addresses the prophet as “son of man” to emphasize his humanness (e.g., Eze 2:6). coming with the clouds of heaven. In ancient Near Eastern literature clouds are often associated with the appearances of deities. In the OT it is Yahweh, the God of Israel, who rides on the clouds as his chariot (Ps 104:3; Isa 19:1). In Canaanite mythology Baal, the son of El, is described as “rider/charioteer of the clouds.” After doing battle with, and defeating, Yamm/Sea, Baal is promised an everlasting kingdom and eternal dominion. Some scholars see echoes of this story in Da 7:9–14. Others argue for a background in Mesopotamian cosmic conflict myths (such as the creation epic Enuma Elish and the Myth of Anzu), which depict a deity (Marduk and Ninurta, respectively) defeating the representative of chaos (Tiamat and Anzu, respectively) and regaining authority and dominion for the gods and for himself. Daniel’s vision has no conflict between the “one like a son of man” and the beasts. The interpretation in vv. 17–27, however, makes it clear that the “one like a son of man” in some way represents “the holy people of the Most High” (vv. 18, 22), who are in conflict with the “little horn” that arises out of the fourth beast (v. 8).

7:16 one of those standing there. Interpreting angels appear in Ezekiel and Zechariah. They are common in apocalyptic literature from the OT on. They do not appear in Mesopotamian literature.

7:17 four kings. See the note on 2:40 concerning the four kingdoms motif in ancient literature. In 2:38 the Babylonian Empire is identified as the first kingdom. Nebuchadnezzar’s experience in ch. 4 is echoed in the description of the first beast; this suggests that the first beast represents the Babylonian Empire. If the “little” horn in chs. 7–8 stands for the same king, then the fourth beast represents the Macedonian Empire of Alexander the Great. There is, however, much debate about the identification of the four kings.

7:18 the holy people of the Most High. The Aramaic text here introduces “the holy ones of the Most High.” In the OT “holy ones” nearly always refers to heavenly beings. The only undisputed use of it to refer to humans is Ps 34:9. The term “holy ones” occurs in the literature written by the sectarians at Qumran and always refers to angels or heavenly beings. The same is true of fragments of Aramaic texts, mainly of the Enochic literature, found at Qumran. In other Jewish literature “holy ones” refers to angels in Wisdom of Solomon 5:5; 10:10 but to humans in Wisdom of Solomon 18:9; 3 Maccabees 6:9; its use in 1 Maccabees 1:46 is unclear. The NIV translates the text as “holy people,” thereby illustrating the fact that scholars are divided over whether “the holy ones of the Most High” in the Aramaic text of Daniel refers to heavenly beings or to the Jews.

7:24 ten kings. At least on this point the text makes it clear that the ten horns represent ten kingdoms/kings. There are ten kingdoms that spring from Alexander’s Empire: Ptolemaic Egypt, Seleucia, Macedon, Pergamum, Pontus, Bithynia, Cappadocia, Armenia, Parthia and Bactria. Yet others believe that the ten are successors to the Roman Empire and, as such, may be still future. There is no agreement as to the identity of these ten kings.

7:25 He will . . . try to change the set times and the laws. In Mesopotamian literature the times and laws are controlled by the cosmic decrees embodied in the “Tablet of Destinies.” These are held by the assembly of the gods or by the chief god on its behalf. In some stories they are misappropriated. In the creation epic Enuma Elish, they are given to Kingu, leader of the renegade gods who support Tiamat. In the Myth of Anzu, the monster Anzu steals them and threatens to use them, thus endangering the stability of the cosmos. Those who identify the little horn of v. 8 and 8:9 with Antiochus IV Epiphanes see here a reference to his persecution of the Jews from 167 to 164 BC. During this persecution he prohibited the keeping of the Sabbath and other Jewish festivals and commanded that copies of the Torah be destroyed (1 Maccabees 1:44–61). time, times and half a time. The word used here for “time” is the same word translated “times” in 4:16 (see note there). The word “times” is simply a plural and does not necessarily suggest two times. The Babylonians were very sophisticated mathematicians, and early on the gods had been represented numerically (Sin = 30; Ishtar = 15). Furthermore, the gods, with their numerical valuations and planetary associations, figured in the astronomical terminology by which the cyclic movements in the heavens were used in calendrical calculations. All of these factors make it very difficult to unpack the significance of this phrase.

7:27 the holy people of the Most High. A strict rendering of the Aramaic is “the people of the holy ones of the Most High.” A text from Qumran contains the phrase “the people of the holy ones of the covenant,” who are clearly the same as “your people Israel.” In 12:7 “the holy people” who suffer are clearly “your people” (i.e., the Jews) of 12:1.

8:1 third year of King Belshazzar’s reign. Likely either 550 or 547 BC. See note on 7:1.

8:2 Susa. The capital of the territory of Elam, some 200 miles (320 kilometers) from Babylon. The city will later become the royal residence of the Achaemenid kings of Persia, so it is a suitable locale for the vision. Ulai Canal. An artificial canal on the north side of the city of Susa that was closely associated with Susa both in cuneiform and classical sources. Though Daniel could have actually made the journey, it is more likely that he is transported in a vision, as Ezekiel sometimes experiences.

8:3–4 ram. In later literature (the first several centuries AD), the signs of the zodiac are associated with countries, and the ram is associated with Persia. There is no evidence, however, that such an association was made as early as the book of Daniel. The concept of the zodiac has its origin in the intertestamental period. a ram with two horns. The interpretation in v. 20 makes it clear that the ram with two horns is the combined Medo-Persian Empire. The later and longer horn represents the Persians. Cyrus II (the Great) of Persia began his reign in 559 BC as a vassal of the Medes. In 550 he rebelled and defeated the Median king Astyages, creating a single Medo-Persian Empire. By 546 he had gained control of the kingdom of Lydia and much of Asia Minor. In 539 he conquered Babylon. Eventually the empire expanded north and west into Greece and west and south through Syria and Palestine to Egypt.

8:5 a goat with a prominent horn. As the interpretation in v. 21 makes clear, this goat represents the coming of Alexander the Great. Between 334 and 331 BC Alexander won a series of battles against Darius III of Persia and became ruler of an empire that stretched from Greece to India. Note that in the OT, the goat is regarded as a stronger animal than the ram (see Jer 50:8).

8:8 the large horn was broken off. At the height of his power, Alexander died of a fever in Babylon in 323 BC. four prominent horns grew up toward the four winds of heaven. After Alexander’s death his empire was eventually divided between four of his generals (see note on v. 22; see also the article “Greek History”). Their realms did not correspond to the four compass points, but “the four winds of heaven” is an Akkadian idiom (see note on 7:2).

8:9 another horn, which started small. In view of what is said in the following verses, there is general agreement that this horn is a symbol for the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes. grew in power to the south and to the east. Antiochus IV campaigned in Egypt to the south (1 Maccabees 1:16–20) and against the Parthians to the east (1 Maccabees 3:27–37). Beautiful Land. Israel (see Da 11:16, 41).

8:10 the host of the heavens . . . the starry host. In the ancient Near East this referred to the assembly of the gods, many of whom were represented by celestial bodies (whether planets or stars). The Bible sometimes uses the phrase to refer to the illegitimate worship of these deities (see note on 2Ki 21:3). On other occasions, the phrase is used for Yahweh’s angelic council (see the article “Divine Council”). Finally, it can refer simply to the stars with no personalities behind them (Isa 40:26). In the destruction described in the Mesopotamian epic “Erra and Ishum,” Erra says that he will make planets shed their splendor and will wrench stars from the sky. Here the starry host represent one side in the cosmic battle and fall temporarily victim to the evil horn, thus suggesting they are some of God’s minions.

8:11 daily sacrifice. The Hebrew word used is taken from the word “regular” in the phrase “regular burnt offering” in Nu 28:3, 10 and elsewhere. It probably refers to the regular morning and evening sacrifices in the temple.

8:14 2,300 evenings and mornings. Many commentators think the “evenings and mornings” refer to the offerings of the daily sacrifice (see v. 11 and note), making the period 1,150 days or about three years and two months. Antiochus had pagan sacrifices offered in the temple on the 15th of Kislev, 167 BC, and the Jews reconsecrated the temple on the 25th of Kislev, 164 BC (1 Maccabees 1:54; 4:52–54), but Antiochus had stopped Jewish rituals sometime before the 15th of Kislev (1 Maccabees 1:44–51). Others, taking the period as 2,300 days, have suggested it is the period between the removal of the high priest Onias III from office in 171 BC and the rededication of the temple. It may be that the number has a symbolic or rhetorical meaning that is now not clear to us.

8:16 Gabriel. This is the first time an angel is named in the Bible. The name means “man of God.” In 1 Enoch 9:1, Gabriel and Michael (cf. Da 10:13) are listed among four archangels, and they are listed among seven archangels in 1 Enoch 20:1–7. In the latter reference Gabriel is said to be in charge of “Paradise.” He is also included among the archangels in the War Scroll from the Dead Sea Scrolls of Qumran. In Lk 1:19 Gabriel brings the message of the birth of John the Baptist to his father, Zechariah, and in Lk 1:26–38 Gabriel relates Jesus’ impending birth to Mary. In the polytheistic religions of the ancient world, the messengers of the gods usually came from the lower ranks of the gods themselves, such as Hermes in Greek mythology.

8:22 four kingdoms. The four kingdoms that eventually arose out of Alexander’s empire were: (1) Macedonia and Greece, ruled by Cassander, (2) Thrace and Asia Minor, ruled by Lysimachus, (3) northern Syria, Mesopotamia and regions to the east, ruled by Seleucus, (4) southern Syria, Palestine and Egypt, ruled by Ptolemy.

8:23 a fierce-looking king. This is Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who ruled from 175 to 164 BC. See 11:21–39 and notes.

8:25 Yet he will be destroyed, but not by human power. This refers to Antiochus’s untimely death by disease in late 164 BC. See note on 11:40.

9:1 first year of Darius son of Xerxes. If Darius is another name for Cyrus (see note on 6:28), this is 539 BC. Cyrus’s father was not Xerxes but Cambyses. However, there is evidence that “Xerxes” was a Persian dynastic throne name; thus, it could have been applied to any of Cyrus’s forebears who are known to us by other names. Alternatively, the Hebrew name translated as “Xerxes” may represent the name of Cyrus’s maternal great-grandfather, Cyaxares. He was significant because he led the Median forces involved in the destruction of the Assyrian Empire.

9:2 the word of the LORD given to Jeremiah. The significance of the date line (v. 1) is that it refers to the time of Babylon’s downfall, an appropriate time for Jewish exiles to take note of Jeremiah’s prophecies about this event. Jeremiah declared that Babylon’s dominance would last 70 years (Jer 25:11–12) and that only after this time would the Jews return from exile (Jer 29:10). Jeremiah may have used the figure 70 as a round number, indicating a lifetime (Ps 90:10; Isa 23:15).

9:3 in fasting, and in sackcloth and ashes. In the OT the combination of fasting, sackcloth and ashes (or dust) is an expression of grief because of some calamity (Est 4:1–3) or penitence (Ne 9:1; Isa 58:5). The practice is also known in Canaan and Mesopotamia (Jnh 3:5–9). See the article “Mourning.”

9:17 your desolate sanctuary. The Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem and the temple in 587 BC, so the temple had been in a ruined state for nearly 50 years.

9:21 in swift flight. Only here in the OT is a divine messenger/angel (as distinct from the seraphim of Isa 6) said to fly. There is no indication here that this is winged flight, especially since Gabriel is called a “man.” Because the Hebrew expression here is unclear, some scholars think it refers to “weariness,” not “flight.” 1 Enoch 61:1 contains the earliest Jewish reference to winged angels. the time of the evening sacrifice. The Israelite day ended at sundown, about 6:00 p.m. The evening sacrifice took place in the late afternoon, around 4:00 p.m.

9:24 Seventy ‘sevens.’ Analogy with the “seven sabbath years” in Lev 25:8 (meaning 49 years) leads most commentators to take this to mean “seventy weeks of years.” Seven years was the sabbatical year cycle, in the last year of which the land was to be left fallow (Lev 25:3–4). Seven sabbatical year cycles led up to the Year of Jubilee, when slaves were freed, debts remitted, and land returned to its original owners (Lev 25). Seventy sabbatical cycles equals ten Jubilee cycles. In the following verses special attention is paid to the first Jubilee cycle (v. 25, “seven ‘sevens’ ”) and to the final sabbatical cycle (v. 27), suggesting that these numbers carry a symbolic significance. This is supported by several verbal and thematic links between Daniel’s prayer and Lev 26:27–45, a passage warning of a period of divine wrath measured in sabbatical cycles, and the apparent understanding of Jeremiah’s 70 years in terms of sabbatical cycles in 2Ch 36:20–21. The symbolic use of weeks and Jubilee cycles is found in intertestamental Jewish literature. The Apocalypse of Weeks in 1 Enoch 91; 93 divides history into ten weeks, divided into segments of seven and three weeks. In the Testament of Levi 16–18, history covers a span of 70 weeks. The Book of Jubilees structures the whole of history by periods of ten Jubilees. There are also examples of the symbolic use of seven and multiples of seven (including time periods) in Babylonian and Ugaritic literature. These symbolic schemas are intended not as strict chronologies but as a way of expressing the significance of history. This has been referred to as chronography and needs to be distinguished from chronology. seal up vision and prophecy. See note on 12:4. anoint the Most Holy Place. The consecration ceremony that involves anointing and purification of the Most Holy Place in Ex 29 (especially vv. 36–37) is sufficient background for understanding this statement. The desecration of the Most Holy Place requires its purification. Assyrian temple inscriptions also refer to the anointing of a temple that is to be repaired and restored by a future prince.