58:4–5 cobra . . . charmer. There are magical incantations in ancient Near Eastern texts for warding off lethal attacks from a snake. One Mesopotamian text describes “serpents that cannot be conjured.” In a Ugaritic text, 12 gods are summoned to offer formulas to a charmer (Ugaritic mlhs = Hebrew mlhs) for neutralizing the poison (Ugaritic hmt = Hebrew hmh) of a snake (Ugaritic hhs = Hebrew hhs). The first 11 charms are ineffective. See note on 140:3.

The metaphor is an attempt to equate the fool/wicked, who will not listen, with a cobra (a term found in both Egyptian and Ugaritic texts) who pays no attention to the snake charmer. Both cause pain and suffering even though it is unreasonable behavior. Although snakes do not have hands to cover their ears (an internal organ), the issue here has to do with unnatural, perverse actions. Along this line, the Egyptian “Instructions of Ankhsheshonq” notes that there is no point in trying to instruct a fool, who will not listen and will hate you for attempting to teach him something. Similarly, the “Instructions of Amenemope” caution that the words of fools are more dangerous than storm winds.

58:10 dip their feet in the blood of the wicked. The poetic imagery is relatively subdued for the violent rhetoric that can be found in ancient Near Eastern culture. One might compare, e.g., the graphic nature of descriptions found in Assyrian royal inscriptions (see notes on 18:38; 137:9). In a Ugaritic text, Anat wades through the blood and gore of her slain enemies. The graphic imagery reflects that these are authentic prayers of people who deeply desire God’s justice to be visited on the wicked. God is willing to hear such outbursts even though, ideally, moderation, mercy and forgiveness would be commendable. The psalmist nonetheless leaves vengeance to God. Examples such as this also remind us that these psalms were not designed to be model prayers for us to draw on (though we may sometimes find them useful in that way). When the disciples asked Jesus to teach them to pray, he did not just direct them to the book of Psalms.

59:6, 14 dogs. See notes on 1Sa 24:14; 2Sa 3:8.

60:2 quaking. The metaphor of an earthquake can describe any kind of catastrophe or social upheaval, here a military disaster (see note on 82:5).

60:3 wine . . . stagger. See note on 75:8.

60:4 banner. See note on SS 2:4.

60:6–8 The list of places in this prophecy name the regions under the sovereign control of Yahweh—either his agents in battle, if Israel, or his enemies whom he will defeat if they are foreign nations. Shechem was an important city in the north-central hill country of Israel, associated with patriarchal wanderings and worship (Ge 12:6; 33:18–20; 37:12), and the place of covenant renewal for the Israelites when they settled the land under Joshua (Jos 24). Since it was closely tied with Israel’s presence in the land and the covenant with Yahweh, it serves here as a central reference point for Yahweh’s possession of the land. Across the Jordan River from Shechem was Sukkoth, a city also associated with Jacob (Ge 33:17) and located near the valley of the Jabbok River. It was conquered by Joshua and given to the tribe of Gad, who settled in the Transjordan (Jos 13:27). Gilead is another name for this same region, and Manasseh is the tribe whose allotment included Shechem. Therefore, these first four geographic references are actually two, and they encompass the northern hill country on the west of the Jordan and the Transjordan on the east. Being just north of Moab and Edom, this region of Israel is appropriate in Yahweh’s claim of possession and challenge to these foreign nations. Ephraim’s tribal region was just south of Manasseh on the west side of the Jordan River, and Judah was the southernmost part of the land. The major foreign threat to Ephraim and Judah was the Mediterranean coastal region of the Philistines to the west. Thus, the list in this prophecy names the majority of the Israelite territories and their most immediate foreign enemies. The specific application of this prophecy is against Edom, east of the Dead Sea (see v. 9; see also title).

60:6 spoken from his sanctuary. The verses that follow quote a prophetic speech given at the tabernacle or temple (see note on 50:7). The contents of this speech may allude to a historical context described in the psalm’s title, or it may be a generic prophecy of victory listing typical enemies of Israel. Its reuse in 108:6–13 demonstrates this possibility.

60:7 helmet. The Israelite tribes named are God’s weapons, hence agents, in the war against hostile foreigners. scepter. Particularly appropriate to describe Judah, since this tribe was the source of the ruling dynasty of David (Ge 49:10).

60:8 Moab is my washbasin. May be a reference to Moab’s proximity to the Dead Sea, but certainly denotes the subjugation of that nation by Yahweh (repeated in 108:9). They are forced into servanthood, being placed in a position where they must wash the feet of their master (cf. Jn 13:5). The container referred to here is usually used for cooking, but is a multipurpose pot/basin that comes in various sizes. Washbasins were typically used for ritual washing or ritual bathing. Washbasins occur in lists of fine gifts in the Amarna tablets. Despite these general comments, the precise imagery here is obscure. on Edom I toss my sandal. Sandals were the ordinary footwear in the ancient Near East, but they were also a symbolic item of clothing. This may have been due to the fact that land was purchased based on whatever size triangle of land someone could walk off in an hour, a day, a week or a month (1Ki 21:15–16). Land was surveyed in triangles, and a benchmark was constructed of fieldstones to serve as a boundary marker (Dt 19:14). Since they walked off the land in sandals, the sandals became the movable title to that land. Casting a sandal is a symbolic, legal gesture employed in those situations where a levir refuses to accept his responsibility to a widow. She in turn removes his sandal, the symbol of ownership and inheritance, and casts it at him. This signifies his loss of inheritance rights to the lands of his relative (Dt 25:9; Ru 4:7–8). Land transfers in the Nuzi tablets also involved replacing the old owner’s foot on the land with that of the new owner. In this instance in the Psalms, God aggressively casts a sandal onto Edom as a gesture of conquest or the assumption of ownership of that nation’s lands.

61:2 ends of the earth. This expression might refer to the earth’s boundary with the underworld, a brush with death similar to the thought of Jnh 2:6 (see the articles “Death and Sheol,” “Death and the Underworld”). In the Mesopotamian Gilgamesh Epic, the hero travels to the horizon (the edge of the earth), where he encounters the mountain through which one descends to the underworld.

61:4 tent . . . wings. The reference to God’s “tent” brings to mind the winged cherubim of the tabernacle and temple (see notes on 15:1; 2Ki 19:15). However, the imagery points beyond this to the metaphor of God’s protective embrace (see note on 36:7).

61:5, 8 vows. See notes on Ge 28:20, 22; Lev 7:12; 27:2; Pr 7:14; see also the article “Nazirites.”

62:4 curse. Unlike modern, western culture where a “curse” is nothing more than profanity, in the ancient world curses were taken very seriously (Ex 21:17). The reason is that a curse invoked a god to bring catastrophe or death upon another person. Even Israelites believed in the reality of other supernatural beings (“gods”; see note on 82:1) who would be fully capable of affecting the well-being of humans when invoked by a curse. In Mesopotamia and Ugarit, prayers and rituals were written to ward off potential injury from enemies who may have cursed the worshiper, especially through the agency of a sorcerer.

62:9 breath. See notes on 49:7–9; 90:3. highborn. As in 4:2, this Hebrew term (beney ish) functions as both a euphemism for the wealthy and powerful as well as a generic term for all men of influence. Both Egyptian and Babylonian texts contain similar expressions for this class of individuals. Babylonian texts, e.g., regularly make the distinction between “a gentleman” and an “ungentlemanly person”—contrasting those who were sophisticated, cultured and refined by virtue of their standing in society with those who were not.

63:2 I have seen you. While only priests enjoyed access to the inside of the sanctuary, the outer court was beautifully adorned with images of cherubs (in the tabernacle, at least), majestic pillars and an ever-burning altar that represented God’s presence and consumed the sacrifices offered after God had answered prayer (see notes on 22:26; 56:12). In addition to the inspiring splendor of temple worship, the metaphor of “seeing God” means that the worshiper has experienced God’s favor (see notes on 4:6; 42:2 [“meet with God”]), an experience in the past that gives the psalmist hope in present distress.

63:7 shadow of your wings. See note on 36:7.

63:9 depths of the earth. See the articles “Death and Sheol,” “Death and the Underworld.”

63:10 food for jackals. Lack of a proper burial meant dismemberment by wild scavengers, which, in the common thought of the ancient world, left no peace for the disembodied spirit (see notes on 141:7; 1Ki 14:11; 2Ki 9:10).

64:3 tongues. See note on 52:2.

64:5 snares. See notes on 124:7; 140:5.

65:1 vows. See notes on Ge 28:20, 22; Lev 7:12; 27:2; Pr 7:14; see also the article “Nazirites.”

65:4 courts. See note on Ps 84; see also notes on 84:3; 100:4.

65:7 seas . . . nations. See notes on 93:3–4; 144:7.

65:12 grasslands of the wilderness. An image of fertility even in the desert. During the rainy season, the desert does support a growth of annuals and wildflowers.

66:10 refined. See note on Pr 17:3.

66:13–15 offerings . . . vows . . . sacrifice. See notes on Ge 28:20, 22; Lev 7:12; 27:2; Pr 7:14; see also the article “Nazirites.”

67:1 face shine on us. This verse echoes the priestly blessing in Nu 6:24–26. Rather than “peace” (Nu 6:26), v. 2 wishes for God’s deliverance of his people to be recognized by all the nations of the earth. The metaphor of the face shining in blessing is found in Ugaritic texts (see note on 4:6) and in Akkadian texts. An example of the latter is from a twelfth-century BC boundary marker invoking blessing upon the Babylonian king Nebuchadrezzar I to be indicated by the radiant shining face of his god Enlil.

68:4 rides on the clouds. In the Ugaritic Baal Cycle, Baal is regularly referred to as the “rider of the clouds.” References can be found in both the Baal Cycle and in the Aqhat Legend. This image of power over the winds and weather stands as another example of the psalmists using descriptions of the gods that were familiar in other cultures. In doing so they are asserting Yahweh’s control over nature and nations (104:3; Jer 4:13)—a control elsewhere attributed to other gods.

68:6 sets the lonely in families. The Egyptian tale of the Eloquent Peasant provides a model for this set of responsibilities to the weak. The king in this Middle Kingdom wisdom piece is called the father to the orphan and the “mother to the motherless.” Dt 24:17–22 describes laws dealing with justice for the vulnerable (see note on Dt 24:17). Ecc 4:8–9 also examines the plight of the one who is isolated, lonely and neglected. leads out the prisoners. In the ancient Near East, the freeing of prisoners (from debtors’ prison) as an act of justice often occurred in the first or second year of a new king’s reign (and then periodically after that). For example, King Ammisaduqa of the Old Babylonian period (seventeenth century BC) cancelled economic debts on behalf of Shamash. Thus, the “jubilee” in this case was primarily concerning those in debt (for either financial or legal reasons), and for the freeing of debt-slaves (see notes on Lev 25:10, 39). Unlike Israel, this Babylonian edict was entirely at the whim of the monarch, and there is no evidence that it was divinely sanctioned. Historically, a proclamation of freedom is recorded by the last king of Judah, Zedekiah (Jer 34:8–10). For these and other characteristics of a just king’s reign, see note on Ps 72; see also the articles “Enthronement in the Ancient Near East,” “Coronation Hymns in the Ancient Near East.”

68:13 the wings of my dove are sheathed with silver. There is no clear consensus on the meaning attached to a dove “sheathed with silver” and “feathers with shining gold.” Some consider it a reference to the battle standards of the fleeing kings, which were topped by a dove, the symbol of the Canaanite goddess Astarte. Others see it as a reference to Israel (see other bird images in 74:19; Hos 7:11).

68:14 Zalmon. Because of the parallel in v. 15 with Bashan, it is unlikely that Mount Zalmon in this psalm is the same as the mountain mentioned in Jdg 9:48 near Shechem. Zalmon means “dark” or “black” and could refer to a peak shrouded in clouds. It would also require more elevation to serve as a snow-covered eminence.

68:15 Mount Bashan. The Bashan region, northeast of Galilee, is a fertile plateau about 2,000 feet (610 meters) in elevation. It is surrounded by extinct volcanic peaks and rolling hills with sufficient forestland to complement its cattle-raising economy (Isa 2:13; 33:9; Jer 50:19; see note on Am 4:1). rugged mountain. Probably refers to the hard to climb, basaltic hills in the Bashan area.

68:16 mountain where God chooses to reign. See notes on 48:1–2; 132:13.

68:18 When you ascended on high, you took many captives . . . gifts. Like the victorious Saul in 1Sa 15:7–15, the triumphant Yahweh is accompanied by a procession of prisoners, loot and tribute payments. A similar image can be found in the Assyrian annals of Sennacherib, who claims to have taken over 200,000 prisoners from Judah, along with their animals and other plunder. The major deities of the ancient Near East were associated with high places, so for Yahweh to “ascend” would be to return to his holy mountain (Jer 31:12), just as Baal used Mount Zaphon as his divine base of operations in the Ugaritic and Canaanite traditions (see note on 48:1–2).

68:23 your feet may wade in the blood of your foes. The poetic language attached to battle reports can at times be rather grisly. This is certainly the case with this phrase (also used in 58:10). The similar image of wading through the blood of one’s enemies is also found in the Ugaritic Baal Cycle. There the goddess gleefully slaughtered whole armies, and she “waded knee-deep in the warriors’ blood.”

68:24 procession . . . into the sanctuary. The New Year’s festival (Akitu) in ancient Babylon included a procession in which the image of the god Marduk was paraded along a “sacred highway” through the streets of the city. The god was guided by the king (“taken by the hand”) up to the Esagila temple, where the image resided during the year. It was not the normal practice for this sort of procession to take place in Jerusalem, since Yahweh could not be represented by an image. However, the ark of the covenant, which functioned as an icon of God’s power and presence, was brought into the city by king David and placed within the tabernacle (2Sa 6), and this is what may be celebrated in this psalm.

68:30 beast among the reeds. Probably refers to the hippopotamus or the crocodile. Both were major hazards along the shores of the Nile River in Egypt. The tomb paintings from Beni Hasan include a number of scenes in which fishermen work while a crocodile lurks in the reeds nearby, or in which papyrus boats are used to hunt this dangerous reptile. Politically, the image is most likely a reference to Egypt.

68:33 rides across the highest heavens. See note on v. 4.

69:1 waters. Deep water was symbolic for any catastrophe of life (vv. 14–15; see note on 93:3–4).

69:8 foreigner to my own family. Scorn from close relatives and friends is a stereotypical theme in individual laments, expressing the depth of anguish (see note on 31:11). Though even today we would feel the weight of such estrangement, it is greatly multiplied in cultures in which a person’s identity is bound up in their place and role in the clan.

69:10 fast. See note on Est 4:16.

69:11 sackcloth. See the article “Mourning.”

69:19 I am scorned. The Israelites believed that if God were to be considered just, rewards and punishments in this life would be proportional to the righteousness or wickedness of the individual. See the article “Retribution Principle.” Consequently, someone who was suffering either from illness or catastrophe, or even at the hands of someone’s actions against them, their very suffering would stand as evidence of their guilt and result in scorn.

69:21 gall. In some contexts, this word refers to poison (e.g., snake venom in Dt 32:33), whereas on other occasions it refers to something bitter. This would match the parallel with “vinegar.” In the former usage it could lead to almost certain death, while in the latter usage it may be understood as some kind of sedative. Presumably, the fast of mourning (v. 10) would be broken with food brought to the sufferer by comforters (e.g., 2Sa 3:35). In this case, however, instead of comfort and nourishment, the mourner receives just the opposite—poison (compare Amos’s charge that justice has been transformed into poison in Am 6:12).

69:28 blotted out of the book of life. The metaphor of divine scribal activity is known in Mesopotamia, usually in expressions of hope that the deity would inscribe one’s name for long life in a heavenly tablet. In the Sumerian Hymn to Nungal, the goddess discusses her justice as she punishes the wicked and brings mercy to those who deserve it. She claims to hold in her hands the tablets of life, on which she writes down the names of the just. Here, the psalmist wishes the opposite for his enemies (see the article “Imprecations and Incantations”).

69:31 horns and hooves. Indicates a full-grown bull (cf. Mic 6:6), an expensive sacrificial animal, which is ritually pure according to the Holiness Code (i.e., Lev 17:1–26:46; see also Lev 11:3–8).

Ps 70 This psalm parallels the wording of 40:13–17 (see the article “Repeated Psalms”).

71:7 sign. The use of the Hebrew term mopet is indicative of an extraordinary event that serves as a sign of God’s power, and in this case judgment or punishment (compare the curses in Dt 28:45–46). This technical term appears often in the narrative of the plagues in Egypt (e.g., Ex 7:3 [“wonders]; 11:9 [“wonders”]), and is used to signal a coming event (1Ki 13:3, 5). The term does not necessarily designate something supernatural as opposed to natural (i.e., a “miracle”). In the ancient world, people did not consider anything truly “natural”—God was involved in everything and therefore “miracle” was a meaningless designation.

71:20 depths of the earth. See the articles “Death and Sheol,” “Death and the Underworld.”

71:22 harp . . . lyre. See the articles “Lyre,” “Music and Musicians.”

Ps 72 Woven together throughout Ps 72 are the themes of justice, peace and domestic prosperity. In the prologue to the Code of Hammurapi, and especially in the epilogue, the king boasts that his just rule also brings peace and prosperity to the cities of his realm. Immediately following the prayer for justice in “Ashurbanipal’s Coronation Hymn,” the priest asks that the king’s dominion might also be characterized by prosperity (abundance of grain; cf. v. 16) and “peace” (Assyrian salimu is akin to the Hebrew salom in v. 3 [NIV “prosperity”]).

Injustice resulted in social chaos (see note on 94:20). In Egyptian thought, the execution of justice by the king expels chaos from creation, bringing harmony and order to the land. Thus, in both Mesopotamia and Egypt, people set their hope on the king for justice and prosperity. In Egypt, this revolved around a pharaoh who participated in the company of the gods and mediated divine blessing to humanity, but this hope never focused beyond the currently living king, except very late in Egyptian history (c. 300 BC), when expectations arose among some that a king would arise to restore the former glory of Egypt. Similarly, Mesopotamians did not conceive of a future king who would usher in an ideal age. People considered only their contemporary king as the agent of the gods who ideally maintained a prosperous social order. In contrast, in the OT one finds a progressively developing theme of hope for a future, worldwide kingdom ruled by a Davidic king on behalf of Yahweh.

72:4 defend the afflicted. Care for the weak members of society is the practical test of a just and good government throughout the ancient Near East, as claimed by Hammurapi (see note on Ps 72; see also the article “Coronation Hymns in the Ancient Near East”). In the Ugaritic Kirta epic, King Kirta is rebuked for failure to “pursue the widow’s case,” “take up the wretched’s claim,” “expel the poor’s oppressor” and “feed the orphan.” In the Egyptian “Teaching for Merikare,” the king is exhorted, “Do justice, then you endure on earth; / Calm the weeper, don’t oppress the widow.”

72:5 May he endure. Along with the hope for justice and prosperity, Ps 72 anticipates a long reign. This strikes another parallel with “Ashurbanipal’s Coronation Hymn,” in which the priest prays that the god Assur would “lengthen your days and years.” as long as the sun . . . moon. These metaphors of an enduring reign are common in royal literature (see note on 89:36–37). A Phoenician royal servant named Azatiwata wished his good name to be remembered “forever like the name of the sun and the moon” (cf. v. 17; 89:36–37).

72:6 May he be like rain. In an agriculturally based society, rain is essential to a prosperous economy. “Ashurbanipal’s Coronation Hymn” asks that in his years there may be constant rain from the heavens. In Ps 72, the king himself is likened to these precious waters that bring life to the earth. This theme occurs again in v. 16, where prayer is offered for abundant grain, like the vegetation that flourishes on the well-watered mountains of Lebanon.

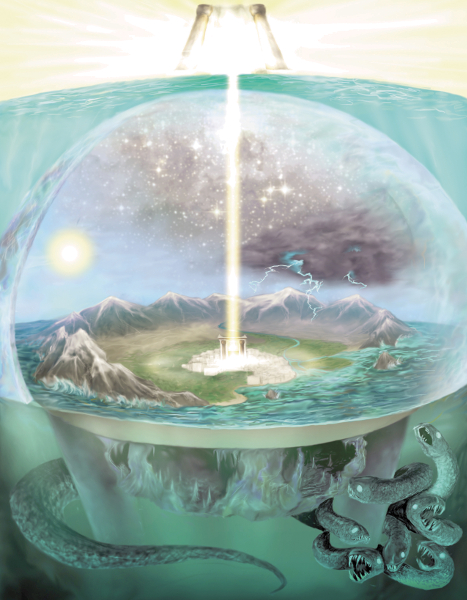

72:8 from sea to sea. Frequently in poetry, the author uses two extremes to express the totality of everything in between (a figure of speech called “merism”). In royal literature, it was used to stress the unlimited extent of a king’s dominion over geographic space and time. There may be an allusion in this verse to the geographic perspective of the ancient Near East that the earth was surrounded by the sea (see note on 24:2). Thus, “sea to sea” meant across the entire world. the River. Here it may refer to the Euphrates River (cf. 1Ki 4:21); but if a more universal view is intended, it could be understood as synonymous with the “sea” (i.e., the cosmic ocean viewed as a current of water, like a river, encircling the earth; see the article “Cosmic Geography”). If this viewpoint is maintained, then in this verse the phrases “sea to sea” and “River to the ends of the earth” are parallel expressions for the distance from one end of the world to the other. The peoples named in Ps 72—those of Tarshish, Sheba and Seba (v. 10)—represent the most remote and hostile places. From the farthest reaches of the Mediterranean Sea in the west to the coastal shores to the south (the Red Sea), and including the desert in between (v. 9), all people will submit to the king, and the most distant nations will bring tribute to him. This is yet another way of expressing the geographic expanse of the king’s dominion from “sea to sea” (i.e., the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, parts of the great ocean that surrounded the earth). Anticipation of an extensive kingdom in Ps 72 has a counterpart in “Ashurbanipal’s Coronation Hymn” as well: “Spread your land wide at your feet.”

72:9 desert tribes. Desert bands created havoc even for the mighty Assyrian Empire, necessitating repeated campaigns against them in order to keep trade routes open. This text is generally emended from the Hebrew tsiyyim (“desert dweller”) to tsarayw (“his foes”). If the original reading is retained, then it could relate back to the use of “Cush” (the desert region of Ethiopia) in 68:31 as a geographic term for the “ends of the earth” and thus follow the coronation promise in v. 8.

72:10 Tarshish . . . Sheba and Seba. In order to indicate the extent of the king’s power, rulers from throughout the world come to him with gifts. Thus, Tarshish, associated with the islands and nations in the western Mediterranean, represents all points to the west (see notes on Isa 23:1; 60:9). Sheba is identified with southern Arabia (Yemen) and the Sabean kingdom (see note on Isa 60:6). Sheba’s location is still disputed, although some place it in Ethiopia or along the northwest Arabian incense road (Isa 43:3).

72:12–14 It is standard in ancient Near Eastern literature to portray the king as lawgiver (cf. Pr 29:14) and defender of the weak (an attribute of God in 35:10). The Egyptian tale of the “Eloquent Peasant” states that the king’s duty is to “father the orphan.” The coronation hymn of the Ur III king Ur-Nammu describes him as the “sustainer of Ur.” In the prologue of the Code of Hammurapi, Hammurapi of Babylon is given the task by the gods to “promote the welfare of the people” and “cause justice to prevail in the land,” so that “the strong might not oppress the weak.” In all of these we can see that the rhetoric related to kingship in Israel follows similar lines to that found throughout the ancient Near East.

72:15 Long may he live! “Ashurbanipal’s Coronation Hymn” asks the deities to give the king a long reign. Stereotypical interjections were used in Egyptian inscriptions, asking life for the king (e.g., “given life, duration, dominion, may he live like Re”). Length of life for a just king meant enduring peace and a good life for his people. gold from Sheba. While there are gold resources on the Arabian peninsula (the most likely location of Sheba), the maritime trade that took place in the Red Sea would have channeled some of the famous gold resources of Nubia (south of Egypt) through Sheba (Eze 27:22). Gold was customarily part of the tribute paid to great kings (see 2Ki 18:14–16 and Sennacherib’s corresponding record of this tribute).

73:9 heaven . . . earth. A common figure of speech called a “merism” occurs when two opposites are mentioned to express the whole. The pairing of the words “heaven” and “earth” is common in the OT (e.g., 96:11; Ge 1:1; Dt 32:1; Job 20:27; 38:33), but a parallel using the pairing of “lips” and “tongue” appears in the Baal Cycle, when the god of death, Mot, threatens to swallow Baal by opening his mouth so wide that one lip touches heaven and the other touches earth, and the tongue touches the stars. In this verse, “heaven” and “earth” are paired to suggest that the wicked have extended their ownership (and power) to control everything.

73:24 take me into glory. The NIV’s inclusion of the word “into” is totally interpretive, not being found in the Hebrew text. The concept of God “taking” a person as a reference to saving his life can be seen clearly in 18:16, where the NIV translates the same phrase as “took hold of me.” The word “glory” is never used in Hebrew as a synonym for heaven, and here refers to an “honorable” resolution to the psalmist’s crisis. His difficulties have brought him shame because suffering was considered a sign of sin and God’s displeasure (see the articles “Retribution Principle,” “Death and the Underworld”). This psalm therefore expresses the hope that God will take action that will save the psalmist’s life and restore his honor. Honor and shame were key issues in the cultures of the ancient Near East (see the article “Honor-Shame Cultures”), including Israel, where identity was found in one’s status in the clan and in the community.

74:1 sheep of your pasture. This is a common metaphor in city laments. The deity is like a shepherd who has dwelt in a hut (i.e., the temple) within the sheepfold (i.e., the city). Abandonment of the city is tantamount to abandoning the people, who are like sheep (cf. 83:12).

74:2 where you dwelt. In Sumerian city laments, it is only after a deity has abandoned his or her city that it is vulnerable to attack. See note on 46:5; see also the articles “Enthronement in the Ancient Near East,” “Hymns to Holy Cities.”

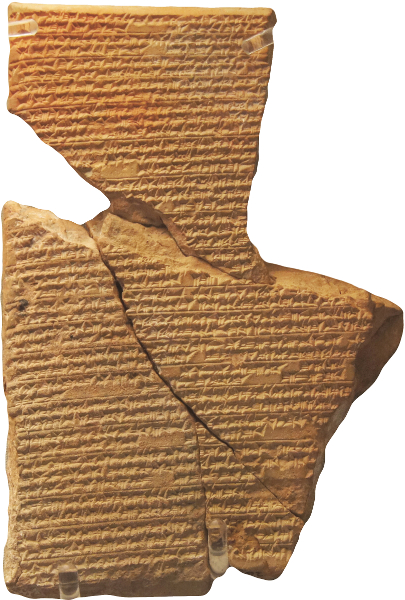

74:3 destruction . . . brought on the sanctuary. The destruction of Jerusalem and the temple (586 BC), described in 2Ki 25:8–17, lies at the heart of this psalm. While there are no extra-Biblical descriptions of this event, the Babylonian Chronicle does record the capture of Jerusalem and the deportation of the king of Judah (Jehoiachin) 11 years earlier in 597 BC (2Ki 24:8–17), at which time the temple treasures were plundered.

74:4 standards. The Hebrew word can refer to a military banner with insignia to distinguish different troop units (see note on Nu 1:52; see also note on SS 2:4, where a different Hebrew word is used for the same object). Because these insignia bore symbols of foreign gods, raising them at the site of the temple was particularly sacrilegious (cf. v. 10).

74:6 smashed . . . with their axes. The Lament Over the Destruction of Ur draws on the same image one might expect of such destruction: into the temple “big copper axes chewed.” Other lines describe the fires that consumed buildings and people alike. These graphic images stir deep feelings for the tragedy. carved paneling. It is difficult to determine whether this refers to carved panels in the temple or to engravings on some of the bronze or gold pieces connected to the temple. What is clear is that the intricate artwork that embellished this temple (as many others in the ancient world) was being ruthlessly destroyed.

74:8 every place where God was worshiped. It is not likely the psalmist would lament the destruction of illegitimate places of worship, whether within the temple complex or at various sites throughout the land (2Ki 21:1–6; 23:1–20). Perhaps these were simply special meeting places for prayer. In cities and villages of the ancient Near East, local shrines other than central, regional temple complexes accommodated the needs of the common people. Even at times when orthodox worship prevailed in Jerusalem, one might expect multiple gathering places that did not necessarily provide for sacrifices or other unauthorized rituals in competition with the Jerusalem temple. Unfortunately, the only places for religious gathering that would leave a clear trace in the archaeological record are those with illicit features such as altars or figurines.

74:13 split open the sea. There is nothing in this psalm to suggest that reference is being made to the dividing of the Red Sea. The context concerns instead the cosmic battle with the sea that is referred to many times in Psalms. The Hebrew verb used here is used only here in this form, making precision somewhat difficult. If splitting is intended, it may be parallel to Marduk’s splitting of Tiamat (sea) that is recounted in Enuma Elish. Others have translated it as a reference to the churning of the sea that sometimes precedes such battles (see note on Da 7:2–3). See the article “Chaos Monsters.”

74:14 Leviathan. Often identified as a crocodile; crocodiles were found mostly in Egypt (where it symbolized kingly power and greatness), but also sparsely in Palestine. However, the multiple heads here and the fiery breath in Job 41:19–21 make the crocodile identification difficult. Alternatively, Leviathan has been depicted as a sea monster—one of the chaos creatures well known in the ancient world (see the article “Leviathan”).

75:2 appointed time. The Hebrew word might be any agreed upon assembly place (Jos 8:14) or specified time (Ex 9:5). The prophet Habakkuk uses this term for God’s chosen time of judgment (Hab 2:3), and in Ps 102:13 God’s time for intervention is simultaneously a time of deliverance for his people. However, it also commonly refers to the assembled festivals of the religious calendar occurring three time a year: Passover and Unleavened Bread in the spring and the Festival of Tabernacles/Booths in the fall (Ex 23:15; Lev 23:2; see the article “Pilgrim Psalms”). Given the worship setting of Ps 75 and its identification as prophetic speech (see note on 50:7), the backdrop for this psalm may be a judgment/salvation speech delivered on the occasion of such a religious gathering (cf. 50:5; 81:3, 8; 95:6–9).

75:3 pillars. See note on 104:5; see also the article “Cosmic Geography.” Here the metaphor of “pillars” extends to the social order, as the following context suggests (see notes on 11:3; 82:5).

75:4 horns. Symbols of strength and therefore a basis for boasting (see note on 18:2).

75:8 cup full of foaming wine. When wine ferments, it produces froth from the released gases, so the metaphor perhaps suggests a particularly well-fermented product. The word picture is expanded with the description “mixed.” At times, wine was mixed with water; but spices were often used to increase the pungency of the drink (SS 8:2). The allure and potentially damaging effect is described in Pr 23:29–35, so it serves as a fitting metaphor of judgment (60:3; Isa 51:17; Jer 25:15, 27). dregs. The sediment-laden portions at the bottom of the jar.

76:2 Salem. This is an abbreviated form of the name Jerusalem, identified as such because of the parallelism with “Zion” in this verse. Jerusalem means “peace.” The same abbreviation is used in Ge 14:18 as the royal city of Melchizedek, who met Abraham after Abraham’s return from the war against the five kings. This psalm, which celebrates Yahweh’s protection of Jerusalem, is closely related to the “songs of Zion” (see the article “Hymns to Holy Cities”).

76:3 he broke . . . weapons of war. Ps 76 alludes to a siege of Jerusalem broken by the intervention of Yahweh. It is not clearly identifiable with any known battle in OT history, but one like Sennacherib’s siege of Jerusalem in 701 BC (2Ki 18:17–19:37) would match the description in the psalm.

77:16 The waters saw you. The psalms speak of the exodus in terms of a cosmic battle between Yahweh and unruly personified forces, such as turbulent waters, which in other ancient Near Eastern texts are hostile gods and goddesses (see the article “Chaos Monsters”).

77:17–18 thunder . . . lightning. These natural phenomena, together with the earthquake (v. 18), are commonly associated with the appearance of a divine warrior (see the article “Divine Warfare”). Strictly speaking, the meteorological events described here happened during the exodus plagues (Ex 9:23–24), and the earthquake was an added phenomenon when Yahweh appeared on Mount Sinai (Ex 19:16–19). However, these descriptions converge in this psalm’s poetic depiction of Yahweh, the divine warrior, throwing back the unruly waters of the sea during Israel’s escape from the Egyptian army (Ex 15:3; see Ps 106:7 and the article “The Red Sea”).

77:19 the sea. See notes on Ge 1:2; Job 7:12; see also the article “Chaos Monsters.” footprints. The gods and goddesses of the other nations in the Near East were portrayed in various animal and human forms. Of interest is the discovery of giant footprints carved into the threshold of a temple at ʿAin Dara in Syria (tenth to eighth century BC). The footprints symbolize the deity stepping from the entrance into the inner sanctuary. Israel’s God revealed himself only in the cloud and pillar of fire (Ex 40:38).

78:2 parable. Wisdom themes are not foreign to hymnic literature such as psalms (see note on 49:1). In the most basic sense, a “parable” is a comparison between two things, but the term is used more broadly for any saying that reflects upon the concerns of wisdom (see 49:4, where it is translated “proverb” and is echoed by the word “riddle”; see also note there). Here the concern is passing on to children the lessons of the fathers (Pr 1:8). A similar value is expressed in the Egyptian “Instruction of Ptahhotep,” in which it is noted that fathers pass instruction on to their children generation after generation by their actions as well as their words.

78:9 men of Ephraim. Ephraim’s tribe was the dominant group among the northern tribes of Israel, so the name “Ephraim” was synonymous with the whole group of northern Israel. When addressing the northern kingdom, the prophet Hosea uses Ephraim’s name for the whole (e.g., Hos 5:3; 6:4; 7:1; 10:6; 11:12). Ps 78 is concerned with the downfall of the northern kingdom and the transfer of prominence to Judah as the place of God’s dwelling (vv. 59–60, 67–68). The use of “Ephraim” at this early point in the psalm (v. 9) signals this emphasis in the psalmist’s historical allusions and admonitions from the past.

78:12 Zoan. The Egyptian city of Djanet, which the Greeks called Tanis. It became the capital city of the delta region in the Twenty-First Dynasty (twelfth century BC). It is in the area where the Israelites were settled in Egypt at the time of Moses.

78:44–48 blood . . . flies . . . frogs . . . locust . . . hail . . . livestock. See notes on Ex 7:20; 8:3; 10:4; see also the article “Interpreting the Plagues.”

78:51 Ham. See note on 105:23.

78:58 high places. See notes on 1Ki 3:2; 11:7; 2Ch 1:3.

78:60 tabernacle of Shiloh. See notes on Jdg 18:31; 1Sa 1:3, 9.

78:69 He built his sanctuary. The theme that gods are ultimately the builders of their own temples is frequently associated in the ancient Near East with the notion that such a temple is rooted in the cosmic realm (either in the realm below the earth’s surface or in heaven). This is a poetic way of affirming its secure and enduring qualities. See the article “Architecture of the Temple.”

78:71 shepherd. See note on 23:1. The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal (c. 1050 BC) identifies the goddess Ishtar as the one who took him from the mountains and named him to be shepherd of the peoples.

Ps 79 The historical event referred to in this psalm is the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonian army in 586 BC (see note on 74:3). Ps 79 is similar in several ways to city laments known from ancient Mesopotamia (see the article “City Laments”).

79:2 dead bodies . . . as food for the birds . . . the animals. In the Gilgamesh Epic, the guardian monster of the cedar forest, Huwawa, tells Gilgamesh that he should have given his flesh to be eaten by birds of prey and scavengers. For exposure of corpses, see notes on 1Ki 14:11; 2Ki 9:10. A common feature of city laments is the graphic description of the fate of the city’s inhabitants. The “Lament Over the Destruction of Ur” reports corpses were piled up by the city gates and that the dead littered the ground like potsherds.

79:5 How long . . . ? This question occurs nearly 20 times in Psalms, usually in connection with a lament psalm. It is found also in Mesopotamia, as the Sumerian “Lament Over the Destruction of Sumer and Ur” asks, “How long will the eye of the enemy be cast on me?”

79:6 Pour out your wrath. While city laments such as the “Lament Over the Destruction of Ur” acknowledge that the destruction was the result of a divine decision, they also contain a section calling for divine retribution on the enemy who showed no limit in their rampage.

79:13 we . . . will praise you. A concluding vow in a city lament is the portrait of praise that will result if the city is restored. The “Lament Over the Destruction of Ur” closes with the hope that the city of the god Nanna might be restored so that praises and rituals can be renewed.

80:1 Shepherd. See note on Ps 23:1. enthroned between the cherubim. See note on 2Ki 19:15.

80:3, 7, 19 make your face shine on us. This refrain finds an echo in v. 14, where God’s act of restoration is parallel to looking down from heaven and watching in a protective manner. Therefore, the metaphor of shining is probably similar to the image of God as the sun (see note on 84:11).

80:4 God Almighty. This Hebrew expression has traditionally been translated “God of hosts,” or when coupled with the divine name Yahweh, “LORD of hosts.” The word for “hosts” is associated with armies (Jdg 4:2; 1Ki 2:5; Isa 34:2). By extension, the same word refers to the “army” of heavenly beings whom Yahweh commands for his service. The psalmist calls for God to intervene militarily on behalf of his people, utilizing his heavenly army on their behalf (see 59:5).

Rashap, the Ugaritic god of war, is called in one text “Rashap of the Army” (Ugaritic sbʾ = Hebrew sbʾ, “host”). It is also possible that there is a connection between the imagery of God as a shining sun (vv. 3, 7, 19) and his ability to intervene with his heavenly “host/army.” A conceptual parallel might be found in a letter from a Canaanite king to the Egyptian pharaoh (c. 1350 BC). The Canaanite king has readied his troops for battle to serve the sun-god, Pharaoh, whom he calls “sun of thousands.” A related letter uses the image for Pharaoh as the sun “over thousands” shining forth over the horizon to muster troops.

80:5 bread of tears. The trauma was so long and severe, it was as though the people’s daily bread was their hardship, a metaphor known from Mesopotamian texts as well.

80:11 Sea . . . River. Given the geographic description, they are likely references to the Mediterranean Sea and the Euphrates River, respectively, though they potentially may be references to the cosmic waters. (In the end this is a difference without a distinction, since the Mediterranean and the Euphrates were part of the cosmic waters.)

80:13 Boars. Not only vicious, powerful animals in the wild, but also unclean for eating (Lev 11:7; Dt 14:8, translated “pig” in both verses). Therefore, the irony of the image is that an unclean animal is destroying the food of God’s people.

81:2 music. See the article “Music and Musicians.”

81:3 New Moon . . . festival. The designation New Moon, i.e., the first day of the month, combined with the description “when the moon is full,” the 14th day, points to the autumn religious festival. This festival opened on the 1st day of the 7th month (Sept./Oct.) with a trumpet call for a sacred assembly. It included the Day of Atonement on the 10th day and culminated with the week-long Festival of Tabernacles, which began on the 15th day (Lev 23:23–44; Nu 29:1–40). See the article “Pilgrim Psalms.”

81:5 unknown voice. See note on 114:1.

81:6 This verse begins the words of the Lord spoken by a prophet at the festival. Prophetic ministry during temple worship was probably common. Assyrian temple prophets served at covenant renewal festivals. See note on 50:7.

81:7 thundercloud . . . Meribah. There was thunder at Mount Sinai (Ex 19:16–24), but it is hard to see how that was an act of rescue, and Meribah—where Yahweh gave water from the rock (Ex 17:1–7)—preceded it. It is therefore more likely that the thundercloud is seen as the weapon of the divine warrior, Yahweh, who delivered Israel from Egypt (the same Hebrew term is used in Isa 29:6 [NIV “thunder”]).

81:16 honey from the rock. While most honey spoken of in the OT is the syrup from the date palm, mention of the rock here suggests bees’ honey from honeycombs in the rocks.

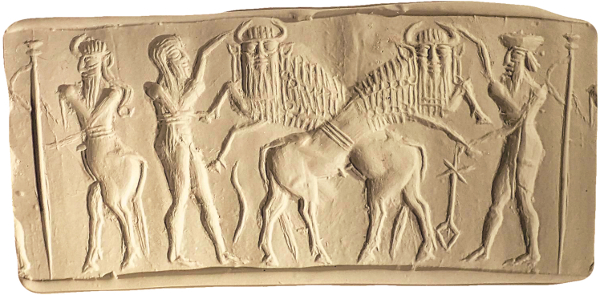

82:1 great assembly. This Hebrew expression can be rendered more lit. “assembly of God” or “divine assembly” (cf. NASB: “congregation”; NRSV and ESV: “divine council”). Yahweh, the God of Israel, stands at the head of an assembly of heavenly beings, which in OT texts are usually called “gods” or “sons of god” (see note on 29:1). The concept of a divine council was also well known among Israel’s Canaanite neighbors and in the religion of Mesopotamia (see the article “Divine Council”).

In the Baal Cycle (see note on Ps 29; see also the article “Psalm 29: A Canaanite Hymn?”), the god Yamm sends messengers who stand before the chief god El and the rest of the gods and goddesses assembled together to render a judgment on Yamm’s request. Likewise, the assembly of the gods in Mesopotamia met to determine the fate of kings and peoples.

82:5 foundations of the earth. While this concept usually refers to the divine ordering of creation (see notes on 24:2; 104:5; see also the article “Cosmic Geography”), it is also used as a metaphor for social order, as it appears in 75:3 as well (see note on 11:3). In the ancient world, people did not differentiate clearly between social order and cosmic order. They were seen as two sides of the same coin. In the myth Enki and Inanna, a list of the foundations of order includes cosmic elements, social and cultural institutions and abstractions of behavior. Threats to order at any of these levels can ripple out into the others.

82:6 I said, ‘You are “gods.” ’ Throughout this psalm, God speaks through the words of a temple prophet (see note on 50:7). God is rendering a verdict of destruction on the heavenly beings who have transgressed the divinely ordained social order. An important aspect of the ancient viewpoint here is that human rulers make decisions that mirror the actions of the “gods.” gods. This term is used both of supernatural beings and of the human rulers who are their agents (see note on 45:6). Therefore, divine retribution reaches into both the human and the heavenly realms in order to vindicate the victims of injustice and oppression (see the article “Imprecations and Incantations”).

83:5–8 The reference to Assyria (v. 8) points to the general period of Assyria’s westward expansion (c. 750–700 BC), although no specific event known outside this psalm corresponds to this list of nations. The number of nations, ten, might suggest a stereotypical list of enemies. Mention of the Assyrian Empire at the end punctuates the list of nine other enemies. From the earliest times, Egyptian scribes used the term “Nine Bows” to refer to nine nations in the region of Egypt, at times including Egypt itself. Over time, the convention changed so that the specific nations listed were immediate enemies of the Egyptian king. The nations listed often described a circle around Egypt, although they were not always in geographic order. The number of nations named also varied at times. For example, the list of “Nine Bows” on Merneptah’s Stele (c. 1207 BC) numbered only eight, including Israel.

Edom, Moab and Ammon were kingdoms southeast, east and northeast of the Dead Sea, respectively (Moab and Ammon being descendants of Lot, v. 8). Ishmaelites and Hagrites were Bedouin tribes in the Arabian desert east of Canaan, and Amalek refers to tribes located to the south. Gebal might refer to a city in Phoenicia (northwest of ancient Israel); however, there is evidence of the existence of a “Gebal” in the region of Edom, which better corresponds with the other places immediately before and after this name in the list. Philistia bordered Israel and Judah on the west and Tyre was a major city in Phoenicia to the northwest. Assyria controlled territories to the north and northeast. Conceptually, the list of nations portrays enemies surrounding Israel and Judah on all sides.

83:9 Midian . . . Sisera and Jabin. During the judges period, God intervened to help Gideon defeat the Midianites (Jdg 6–7), a tribal group later associated with the Ishmaelites. About this same time, Sisera and Jabin, from Hazor to the north of Israel, were defeated by Deborah and Barak (Jdg 4–5). By selecting these examples, the psalmist alludes to famous victories in geographic regions corresponding to the list of enemies in vv. 5–8.

83:10 Endor. Not mentioned in the account of these battles in Judges (see previous note), but it is in the vicinity of both of them. The eastern end of the Jezreel Valley is about 10 miles (16 kilometers) wide from north to south. The north end is blocked off by Mount Tabor, while the south end is blocked off by Mount Gilboa. The ten-mile (16-meter) stretch between the two is broken into two passes by the smaller hill of Moreh. Endor is located in the middle of the northern pass, between the hill of Moreh, where the battle of Midian took place, and Mount Tabor, where Deborah and Barak mustered their troops.

83:11 Oreb and Zeeb . . . Zebah and Zalmunna. Nobles killed in Gideon’s battle against the Midianites (Jdg 7:25; 8:3, 12, 21).

83:18 you alone are the Most High. In the ancient world, the existence of a god was understood in terms of its effective activity as a god. A being who was inactive, ineffectual, incompetent or lacking power or authority was not a god. This statement identifies Yahweh as the only being justifiably classified as a god. See the article “Monotheism, Monolatry and Henotheism.”

Ps 84 Hymns that extol holy cities and their temples are known from the ancient Near East (see the article “Hymns to Holy Cities”). Ps 84 concentrates on the delights of a visit to Jerusalem and its temple where God dwelt. The language of “courts” (vv. 2, 10) is consistent with the view of a temple as the “palace” of God (see note on 100:4). A similar sentiment is illustrated in an Egyptian prayer from c. 1200 BC in which a religious pilgrim lingers in the temple court.

84:3 a home . . . near your altar. While the Most Holy Place, containing the ark of God’s presence, was the most sacred place in the temple, it was accessible only to the high priest (Lev 16:1–2), and the altar of incense, which was within the Holy Place, could only be approached by a priest (2Ch 26:16–18). Therefore, the altar of sacrifice in the temple court was the most important center of activity for the average worshiper. The psalmist marvels at the good fortune of even a small bird to have a nest so near, probably tucked into a niche somewhere on the structure of the sanctuary itself overlooking the court and altar. Even more blessed are the priests who have the privilege of living in the temple compound (v. 4).

84:4 those who dwell in your house. Being constantly in deity’s presence is considered a privilege to be longed for throughout the ancient Near East. The Babylonian king Neriglissar expresses to his god that he wants to be where his god is forever. Another text requests that the king might stand before the god forever in adoration. The Hymn to Marduk requests that the worshiper may stand before the deity forever in prayer, supplication and entreaty. In the third millennium BC, Sumerian worshipers tried to accomplish this objective by placing statuettes of themselves in the posture of prayer in the temple. In this way they would be continuously represented in the temple.

84:6 Valley of Baka. If this is a reference to a geographic location, it is obscure. The word Baka means “weeping,” but this would also be difficult to understand. The alternative suggestion is that the word describes a tree, particularly, the balsam (see note on 2Sa 5:23–24). None of these help locate the valley or identify its significance.

84:9 our shield. As in 89:18, the king is identified with the shield as an image of protection (see note on 3:3). your anointed one. See note on 1Sa 2:10.

84:10 doorkeeper. See note on 1Ch 9:17.

84:11 sun and shield. Both offer protection. For the shield that is obvious, but we would not necessarily think of the sun in those terms. Nonetheless, Assyrian kings use the metaphor of their protection spreading over the land like the rays of the sun.

85:8 I will listen. May refer to a prophet in the temple waiting for a message from God, which in this psalm would comprise vv. 9–13 (see note on 50:7). Prophets were often thought to receive their messages by being allowed to listen in at the divine council (see the article “Divine Council.”

85:10 righteousness and peace. Peace is what people experience in the absence of fear. It results when righteousness prevails (Isa 32:16–17). A similar pairing of these two concepts was shared by the Egyptians, who expressed the combination with one word: maat. For the Egyptians, maat was the natural order of the universe, “the way things ought to be.” It could be translated “order” or “justice,” so it embraced social justice leading to prosperous life for the community. A good illustration of this is found in the speeches of the “Eloquent Peasant,” in which a peasant appeals for justice from a local magistrate. His poem links the execution of social “justice” (maat) with the “fair wind” that accompanies a smooth and prosperous sail on the sea. When chaos plagues Egyptian society, it is due to the absence of maat in the king’s rule. In this verse, righteousness and peace “kiss” when God blesses his people. See note on Ps 72.

86:8 none like you. In ancient Near Eastern hymns, proclaiming the incomparability of a god or goddess is well attested. Whichever of the great gods a person was worshiping would be the “greatest” at that particular moment of worship. For example, in one hymn the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (c. 650 BC) calls his national god, Assur, “lord of the gods” and “surpassing” all other gods, who themselves cannot fully comprehend him. In another hymn, he proclaims Marduk as the most high and most powerful, whose deeds make him lord of the gods. At the same time, he claims that the goddess Ishtar has “no equal among the great gods.” Some expressions of worship to the Egyptian sun-god declare his incomparability: “one without parallel,” “the one of surpassing power” relative to the other gods, “who conceals himself from all the gods . . . there is no comprehending him.”

Consequently, we can see that such expressions are not solely associated with monotheism, though they comport well with it. Even the statement “you alone are God” (v. 10) has to be understood in the context of how the Israelites and their neighbors thought about the gods (see note on 83:18).

86:17 Give me a sign. Perhaps this request is best understood as an expectation of prophetic response in the context of worship (see note on 50:7). The demonstration of God’s favor by some visible or tangible form would vindicate the psalmist in the sight of his enemies. This concept is illustrated in a letter from a Canaanite king to Pharaoh (c. 1350 BC). The king expresses his wish for a gift from Pharaoh as a visible symbol that he enjoys Pharaoh’s favor: “bestow a gift upon his servant so that our enemies may see (it) and be humiliated.”

87:1 founded his city on the holy mountain. In OT thought, Jerusalem (also called “Zion,” v. 2) was at the center of God’s kingdom and the world. For the importance of holy cities and mountains in ancient Near Eastern religion, see applicable notes on Ps 48; see also the article “Hymns to Holy Cities.” The psalmist here marvels at the stability of Jerusalem resulting from Yahweh’s presence in his temple, which has become the anchor point for the entire cosmos (see the article “Sacred Space”). This thought is similar to a Babylonian hymn in praise of the god Nabu’s temple at Borsippa, described as having a summit that reaches the clouds, while its roots penetrate into the netherworld.

87:4 Rahab. Its identification is not clear. In some contexts, the name refers to the chaos serpent (see the article “Chaos Monsters”). However, the names of mythical monsters can be used symbolically for an enemy nation, and here “Rahab” is another name for Egypt (see Isa 30:7), the great empire to Israel’s southwest. Babylon. One of the oldest and most highly esteemed cities in Mesopotamia (Ge 10:10); it is representative of the peoples from this region of the ancient Near East. Philistia . . . Tyre . . . Cush. No historical situation needs to be sought here, because the text is simply listing some of the nations that will be counted among those who acknowledge Yahweh (whether politically or spiritually). The list in this verse includes the great powers, Egypt (Rahab) and Babylon, the near neighbors, Philistia (southwest) and Tyre (northwest), and the distant nation Cush (i.e., Nubia), south of Egypt).

87:6 register of the peoples. In the ancient world, royal estate cities typically housed the administration (composed largely of relatives of the king), and their citizens enjoyed certain privileges, including exemption from taxation, corvée labor, military duty and imprisonment, as well as being beneficiaries of the most beautiful and elaborate building projects. Such privileges (Akkadian kidinnutu) were enjoyed, e.g., by Babylonian cities such as Nippur, Sippar and Borsippa based on their statuses as religious centers rather than as political capitals. Political capitals such as Nineveh and Babylon also were endowed with similar status. It is presumed that records would be kept to identify those who enjoyed such privileges. In this verse the psalmist alludes to the privileged status of those born in Zion.

87:7 my fountains. A common image in ancient Near Eastern art is a deity holding a vessel from which waters flow, bringing blessing to the worshipers. Perhaps this lyric, sung by converts to the God of Zion, alludes to the idea that the dwelling place of God is the origin of all that blesses life (see note on 46:4).

88 title Heman the Ezrahite. Along with Ethan (see Ps 89 title), Heman is listed as one of the famous wise men in Solomon’s time (1Ki 4:31) and was appointed one of the Levitical musicians during the time of David (1Ch 15:17, 19).

88:3–7, 11 See the articles “Death and Sheol,” “Death and the Underworld.”

88:10 Do their spirits rise up and praise you? The glorification of God’s name on earth comes through the praises of his people (22:3, lit. “enthroned on the praises of Israel” [ESV, NASB]). Conversely, the dead contribute nothing in this regard. This notion forms the basis of a natural appeal to God for intervention. A similar plea is echoed in a Mesopotamian prayer to Marduk observing that the god has no profit from one who has turned to clay or dust. This very human perspective is also evident in Hittite laments.

89:3 I have made a covenant . . . sworn to David. The theme of God’s covenant with David is introduced in vv. 3–4 and expanded in the prophetic proclamation that begins in v. 19. David and his descendants were chosen by Yahweh to rule on the throne over the people of Israel (132:11–12; 2Sa 7). The covenant announced in these prophetic speeches promises unconditionally that David’s dynasty would always be the rightful heirs to the throne. However, individual descendants who did not follow God’s laws could be removed from kingship. Unconditional and conditional elements are compatible in ancient Near Eastern treaties and wills, with wording similar to that of Ps 89; 132; 2Sa 7. A great king might grant to a loyal subject certain guarantees of property. The property would always belong to the family; however, in the future any disloyal individual could be disciplined by the great king and lose their right to the land. However, the land remains in the possession of the family line. While the form of these royal grants is not an exact parallel with the Davidic covenant, the similar language illustrates how unconditional and conditional themes might work in compatible fashion in the same document. Another important feature of these covenants was the family terminology (see notes on Ps 2).

89:6 among the heavenly beings. See the article “Divine Council.”

89:9–10 You rule over the surging sea . . . crushed Rahab. See the article “Chaos Monsters.”

89:12 You created the north and the south. A poetic way of saying the same thing as v. 11 (i.e., God created everything) by naming two extremities in order to include everything in between. A similar use of these two compass points can be found in Eze 20:47; 21:4. north. The Hebrew word (tsaphon) is perhaps significant in that the same Hebrew word is the name of a high mountain in Syria to the north of Israel: Zaphon. Although Yahweh’s dwelling is most often associated with Mount Zion in Jerusalem, his presence is sometimes attached to other high mountains, like Zaphon (see note on 48:1–2). south. Also the place of Yahweh’s mountain dwelling (Mount Sinai/Paran, Dt 33:2). In the ancient Near East, gods were often associated with high places, especially mountains, and worshiped there. Canaanite myth placed Baal’s palace on Mount Zaphon. Mount Tabor and Mount Hermon in northern Israel were likewise ancient worship sites.

89:14 Righteousness and justice. Frequently depicted on the pedestal of Egyptian thrones is the hieroglyph for justice (maat, see note on 85:10), conveying the importance of this value to the rule of a good king. See note on Ps 72.

89:18 shield. A symbol of protection; here it is an image for the king, to whom the people have looked for their security (see notes on 3:3; 84:9, 11). The people affirm their dependence on the king and ultimately on the Lord, to whom the king belongs; however, this psalm laments the king’s downfall.

89:19–37 Many of the expressions in these verses (see also Ps 2; 110; 132) are similar to divine words of affirmation found in Assyrian royal prophecy, in which the god sustains the king, crushes his enemies, and establishes his house. Throughout the ancient Near East, prophetic oracles offered great assurance to the king, supported his authority in the eyes of the people, and functioned to solidify the relationship between the deity, the king and the people. In Psalms, it is also the case that these prophetic words are supportive of the king, in contrast to the prophetic books of the OT, in which the prophets often took a critical stance against the king.

89:19 vision. This word indicates that the ideas expressed in the following verses originated from prophetic speech (cf. Isa 1:1; Hos 12:10). The royal promises to David and his descendants began with the prophet Nathan (2Sa 7), through whom Yahweh announced his covenant, and are found in other prophetic psalms (Ps 2; 110; 132:11–18). Such prophetic oracles were sometimes uttered in a temple setting, which fits well the background of the psalms, and here, the use of the Hebrew term hesidim (“faithful people”) refers to the community gathered for worship (also in 30:4; 52:9; 145:10; 149:1; and “consecrated people” in 50:5).

89:20 I have anointed him. See notes on 1Sa 2:10; 10:1.

89:27 I will appoint him to be my firstborn. As the eldest son in a family, the “firstborn” had customary right to a major share of the inheritance (Dt 21:15–17) and took leadership of the family clan upon the father’s death (see the article “Inheritance Rights and Birthrights”). In the ancient Near East, the custom for royal succession was that the eldest son would be the next king. However, exceptions are known and sometimes led to internal political turmoil. For example, Ardi-Mulissi, the eldest living son of Sennacherib (704–681 BC), was replaced by Esarhaddon, a younger son, as the heir to the throne (see the article “The Death of Sennacherib”). The former assassinated his father and civil war ensued. Similarly, political tension resulted from David’s selection of Solomon over an older brother for succession (see 1Ki 1). Against this backdrop, we might conclude that if the Davidic king is “firstborn” heir of the Creator of the world, then he is also the preeminent king (“most exalted,” v. 27) over all world rulers.

89:36–37 his throne endure . . . like the sun . . . like the moon. Because of their enduring presence in the universe, the imagery of sun and moon were used in royal inscriptions for the stability of a king’s dynasty. A letter to the Assyrian king Esarhaddon (c. 670 BC) expresses the wish that his kingship and that of his descendants might be established as firmly as the moon and sun. In Ps 89, they are likened to witnesses to the covenant, thereby ensuring its validity for all time.

90:3 Return to dust. Death is decreed. According to Mesopotamian myth, the chief god Enlil became annoyed by the noise stemming from the ever-growing human population. After the flood, which was sent by the gods to wipe out humanity and thus alleviate the noise, population growth was limited by withholding immortality from humankind. In the Gilgamesh Epic, the god Enki describes how after the flood the gods swore that people should not have eternal life. The psalmist recognizes that divine judgment and death are the result of sin (v. 8). dust. See note on 104:29–30.

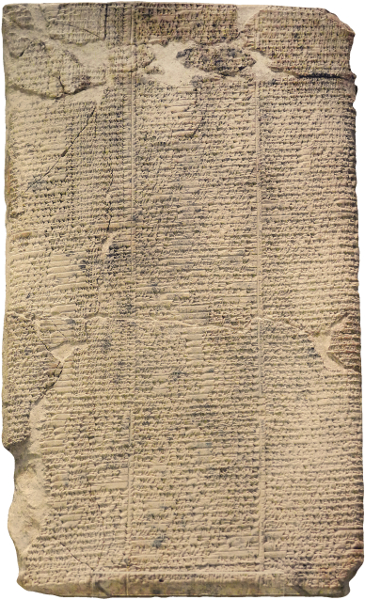

90:10 seventy years. As early as 100 BC, the Apocryphal Book of Jubilees (Jubilees 23:15) contrasts the preflood life spans approaching 1,000 years (v. 4) with the postflood expectancy of 70 years (here). A similar chronological schema is preserved in the Sumerian King List, which records the reigns of kings in the tens of thousands of years before the flood, but diminishing to hundreds of years and then tens of years after the flood.

On the basis of human skeletal remains, anthropologists have estimated the life span of people living in Canaan during Biblical times. A little over 40 percent reached adulthood (20–49 years of age) and nearly 10 percent lived beyond 50 years. Ancient Egyptian tradition idealized the maximum age as 110, as Pharaoh Amenmesses (c. 1200 BC) hoped, since that was the destiny of the righteous man. But more realistically, Egyptian tradition also set the prime of life between 40 and 60 years. Mesopotamian expectations set 40 years as “prime” with 90 years as a maximum. Records show that scribes and even many slaves lived 60 to 80 years. The mother of the Babylonian king Nabonidus lived 104 years. These cultural norms all accord with the expectation of the psalmist.

90:17 establish the work. Not only did ancient Israelites recognize the ephemeral nature of life and human endeavor (vv. 3–6; Ecc 2:11, 16; Isa 40:6–7), but a similar humility marked Mesopotamian thought. A Mesopotamian wisdom text that treats the transitory nature of life states that humans as well as their achievements do not last. The text goes on to admonish the reader to attend to his god. In this verse, a confident trust breaks through that God is able to make human efforts count for good.

91:1 the shadow of the Almighty. The shadow offers protection and is usually referred to as the “shadow of your wings” (36:7; see note there).

91:3 fowler’s snare. See notes on 124:7; 140:5. pestilence. Usually translated “plague” in the NIV, this Hebrew word refers to acts of God’s judgment, which may include disease, but more broadly includes any disaster with fatal consequences (cf. Jer 27:13; Eze 33:27). Some commentators associate pestilence with demonic forces, which fits the imagery of a pestilence that “stalks” (v. 6). Indeed, this word and its synonym, “plague” (v. 6), are coupled with a word that is also the name of a deity of pestilence, war and the underworld in ancient Near Eastern texts: “Rashaph” (Hebrew resheph, see Dt 32:24; Hab 3:5 [both translated “pestilence”]). In the ancient world, all of these issues were understood as interrelated.

91:4 under his wings. See note on 36:7.

91:5–6 terror of night . . . the darkness. The darkness of night creates an inherently more dangerous setting; and perhaps due to the intensification of fever at night, illness in particular was feared. A nighttime prayer from Mesopotamia to the god Nusku implores the god to dispel the fears connected with the night (e.g., demons, wicked people) and to appoint to him a “watcher of well-being and life” to guard him until daybreak.

91:6 pestilence. See note on v. 3.

91:11 angels . . . to guard you. In the ancient Near East, it was, of course, deities rather than angels who served as guardians. Mesopotamians believed that personal gods or family gods offered special care and protection that the great cosmic or national deities would not be bothered with. The Akkadian texts also speak of guardians of well-being and health, as well as guardian spirits. These spirits were assigned to an individual by the deity just as here. The protection that was expected in the ancient Near East was against demonic powers that were believed to be the cause of illness and trouble. Related to that was the danger of magical spells and hexes that could be pronounced against someone. The Israelites undoubtedly believed in the reality of the demon world, and many Israelites would not have successfully divorced their thinking from the magical perspectives of their neighbors. Nevertheless, the psalmist does not typically understand the problems he faces in those terms. While the OT offers no evidence for personal, guardian spirits such as those implied in the Mesopotamian texts or affirmed in some Christian traditions (“guardian angels”), Ps 91 does express confidence that Yahweh sends servants from the heavenly realm to aid his people in time of need (see note on 103:20).

91:13 cobra . . . serpent. See notes on 58:4–5; 140:3.

91:14 I will rescue him. The previous verses are words of encouragement on behalf of the worshiper; beginning in v. 14, however, God himself speaks. Prophetic speech in the context of worship was not uncommon to ancient Israel, and it is preserved in some psalms (see note on 50:7). The original setting for most psalms is a matter of speculation. While the first performance of this psalm might have been addressed, e.g., to a king preparing for battle (see note on Ps 20), its preservation and subsequent use was for anyone seeking protection from God. Such reapplication of original compositions is attested across the ancient Near East (see the articles “Community Laments in the Ancient Near East,” “Repeated Psalms”). In this case, the original prophetic promise becomes a word of encouragement that God is sovereign over any danger and able to come to the aid of his people. This is not unlike contemporary use of any prophetic text from which a timeless principle is drawn for general application.

92 title A psalm. A song. For the Sabbath day. This is the only psalm that is designated for the Sabbath. There is little indication in the OT of any special worship ceremonies on the Sabbath. It has been suggested that this psalm accompanied the daily offerings on the Sabbath.

92:1, 3 music. See the article “Music and Musicians.”

92:3 lyre. See the articles “Lyre,” “Music and Musicians.”

92:10 horn. See notes on 18:2; 132:17. oils . . . poured on me. See note on 23:5.

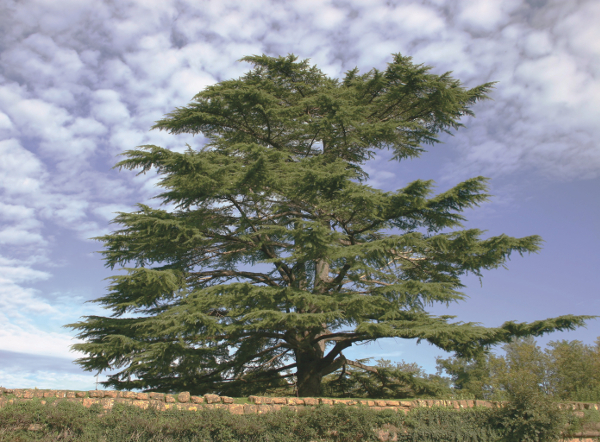

92:12 palm tree. Reaching heights of 70 feet (21 meters) and living up to 200 years, the date-palm tree was a conspicuous sight of fertility along waterways in the arid climate of the ancient Near East. cedar of Lebanon. The rain-drenched, mountainous regions to the north of Israel were famous for towering cedar forests (see notes on 29:5; 2Sa 5:11; 1Ki 5:6; 6:15). Appreciation for the beauty and shade of trees led to the planting of groves in palace compounds. Solomon even simulated a forest by incorporating a high concentration of cedar beams into his palace (1Ki 7:2–4). There were no such groves in the court of the temple, but the metaphor drawn from royal architecture was meaningful in the context of Yahweh’s temple court.

93:1 The LORD reigns. See note on 99:1. world is established, firm and secure. See notes on 24:2; 104:5.

93:2 Your throne was established. See note on 29:10; see also the article “Enthronement in the Ancient Near East.”

93:3–4 The seas . . . the great waters. The link between defeating the sea, the paramount representation of nonorder, and attaining kingship, the primary human mechanism of order, was common in the ancient Near East. The Babylonian Creation Epic, in which Marduk defeats the sea, concludes with the admonition for people to sing the song of Marduk’s victory over Tiamat (the sea) and his ascension to kingship over the gods. In the Ugaritic Baal Cycle, the god battles the sea in order to gain control of chaos and earn the right to be king. See the article “Chaos Monsters.”

94:1–2 shine forth . . . Rise up, Judge. In Mesopotamia and Egypt, the sun-god was viewed as the god of justice. Using a similar metaphor of the sun’s penetrating rays, the psalmist appeals to Yahweh for justice (see notes on 19:7; 84:11).

94:20 corrupt throne. Corrupt government is a great evil to citizens of any community, and the value of justice extended universally. The Mesopotamian text Advice to a Prince warns of divine retribution for any king who oppresses his subjects. The god would bring chaos and devastation. The text continues with threats to advisors or officers who likewise fail to heed justice, and it applies these warnings for the benefit of specific cities in Mesopotamia. We therefore see that justice was a primary concern throughout the ancient world.

95:1 let us sing. See notes on Ps 149.

95:3 King above all gods. The supremacy of one deity over all other gods in the divine council is a prominent theme in ancient Near Eastern religions. In the Babylonian story of the exaltation of Marduk (the Creation Epic), Marduk’s reward for defeating the gods of chaos was kingship over all the gods. Together they prostrated themselves and declared him their king. When the Assyrian Empire controlled Babylon, the chief god of Assyria, Assur, was regarded as supreme. The Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (c. 650 BC) declared in his Hymn to Assur his intention to magnify this king of the gods. After Baal’s defeat of Yamm, the goddess Athirat argues that Baal should have his own palace: “Our king is the Mightiest Baal, our ruler, with none above him.” The Hymn to Osiris, an Egyptian god, opens with the words: “Hail to you, Osiris, lord of eternity, king of the gods.” Yahweh’s superiority to other gods suggests his ability to give Israel victory over the other nations. See the article “Divine Council.”

95:4 depths of the earth. The word “depths” refers to something inaccessible to be searched or explored (cf. Job 38:16). In this verse, the “depths of the earth” are set in contrast to the highest mountain tops. In OT geography, the lower-most recesses of the earth were thought to be rooted in the deep sea (see the article “Cosmic Geography”).

95:6 bow down in worship. To prostrate oneself, a common description of homage in the ancient world. One Egyptian portrait shows subservient people moving through three different postures in homage—standing with hands raised, kneeling and lying prostrate.

95:7 people of his pasture. The ideal king in the ancient Near East was likened to a shepherd, an image of care and protection, a function of the gods whom the king represents (see note on Ps 23:1). The picture here is even more intimate, because Yahweh, the king (v. 3), is also viewed as one who created his people by his own hand. One Egyptian wisdom text refers to humanity as god’s “cattle” for whom he provides (see note on 104:29–30).

95:8 Meribah. Means “strife” (translated “quarreling” in Ge 13:8). It refers to a place in the wilderness, “Rephidim,” exact location unknown. Here the exodus generation quarreled against Moses over the lack of water (Ex 17:1–7). Massah. Related to the word “tested” in v. 9; it is another name given to the same location in recognition that Israel put Yahweh to the test as their provider (Ex 17:2, 7). At the same time, the Israelites were themselves being tested by Yahweh for their fidelity, which was one of the general purposes of the trials in the wilderness (81:7; Dt 8:2).

96:1 a new song. Several times the OT records the creation of new music. This was common after military victories (e.g., Ex 15:1; Jdg 5:1; 1Sa 18:6–7). Ps 45, e.g., originated as a wedding tribute (45:1); and when the ark was brought to Jerusalem, David commissioned a “new song” (v. 1; 1Ch 16:7). Ps 96, or at least its first edition, originated from this context (compare Ps 96 with 1Ch 16:23–33). Any fresh experience of God might offer an occasion for the composition of a “new song.”

96:4–5 feared above all gods . . . idols. Some psalms indicate that, in the heavenly realm, divine (supernatural) beings do exist, but they are inferior in every way to Israel’s God, Yahweh, who exists in a class of his own (see notes on 29:1; 82:1; 86:8; 95:3). Hence, they are not really “gods” worthy of worship, as the other nations understand them to be. Because of this, the psalmist uses a derogatory Hebrew word for “idol,” meaning “useless” or “vain.” See the article “Divine Council.”

96:10 The LORD reigns. See note on 99:1.

97:1 The LORD reigns. See note on 99:1.

97:2 Clouds and thick darkness surround him. The image of a rampant God storming through the heavens in a cloud chariot is a common one (68:4; 104:3; Jer 4:13). Such descriptions of storm theophany may be found in the texts that speak of the Ugaritic god Baal. In both the Aqhat Legend and the Baal Cycle, Baal is referred to as the “rider of the clouds” (see note on Job 37:2–5). Baal’s attributes—commanding the storms, unleashing the lightning, and rushing to war as a divine warrior—even appear in the Egyptian Amarna letters. The characteristics of Yahweh as creator, fertility god and divine warrior share a great deal in common with these earlier epics. One of the ways that Yahweh presents himself as the sole divine power for the Israelites is by assuming the titles and powers of the other ancient Near Eastern gods.

97:5 mountains melt like wax before the LORD. Similar to a Hebrew inscription found at a trading post in the southern desert of Judah (Kuntillet Ajrud, c. 800 BC). While the words for the deity in that inscription are used of Canaanite deities, they are also generic terms for “god” (el) and “lord” (baal), and they therefore could refer to the God of Israel. Lord of all the earth. In v. 7, the psalmist will denounce the status of the gods of the nations; and if Israel’s God is truly the only God, then he reigns over the territories and nations of these “gods.” The concept of Yahweh’s universal rule is affirmed in a cave inscription, possibly carved by refugees of the Babylonian invasions (c. 600 BC, or perhaps c. 700 BC, which would date to the Assyrian crisis): “Yahweh is the god of the whole earth.” This is an expression of hope and faith that Yahweh will prove stronger than the gods of the other nations. A dedication inscription of a southern Mesopotamian king (Ishbi-Erra, c. 2000 BC) begins: “For the god Enlil, lord of the foreign lands.” Over a millennium later, when Assyria was supreme in northern Mesopotamia, their chief god Assur was proclaimed “the lord of the lands.” Egyptian ideals of their universal god find clearest expression during the reign of Akhenaten, who advanced the sun disk as sole god by declaring him Lord of all the earth.

97:7 images . . . idols . . . gods. See notes on 96:4–5; 135:15; see also the article “Making an Idol.” For the “gods” worshiping Yahweh, see note on 29:1.

98:1 holy arm. See note on Ex 6:1.

98:5 harp . . . singing. See the article “Music and Musicians.”

98:6 trumpets . . . ram’s horn. See note on Jos 6:4.