Annotations for Lamentations

1:1 the city. Jerusalem. Why would the destruction of Jerusalem be such a momentous event? First, there is the general significance of a city in the ancient Near East. Up to the time of the fall of Jerusalem the economy of the region was pastoral-agrarian. However, there is ample evidence of “permanent” settlements inhabited by people engaged in a variety of pursuits other than farming by the fourth millennium BC. The material remains of these cities indicate they were centers of security, crafts, trade and religion.

Second, there was the sense of security that cities tended to offer. The terrain of Judah offered a degree of natural security. The Dead Sea and wilderness offered protection to the east. The relatively steep ascent and deep v-shaped canyons to the west presented an impediment to invading forces. In addition to these natural defenses, fortification of a city like Jerusalem provided a measure of security for the surrounding population as well. By the time of the united monarchy in Israel there was a fairly well-developed administrative structure.

Third, and perhaps the most significant, there is the spiritual factor. Dt 12:5 indicates that God would “choose [a place] from among all [Israel’s] tribes to put his Name there for his dwelling.” This claim established the spiritual and theological significance of a particular place. By bringing the ark of the covenant to Jerusalem, David made Jerusalem the spiritual center. Under David and Solomon Jerusalem also became the economic capital of Israel. Later, Isaiah would call Jerusalem the “holy city” (Isa 52:1). Throughout the Psalms and the Prophets, “Zion” represents the Lord’s presence. It was common for cities in the ancient Near East to have patron deities who were seen as the real king.

When the kingdom of Judah fell to the Babylonian Empire (586 BC), the temple and the palace were destroyed, along with the rest of the capital city and the leadership, and much of the population was carried away captive. This devastation was not merely sociopolitical, it was deeply theological and spiritual as well.

1:4 appointed festivals. There were three pilgrimage festivals in the Israelite calendar: the Festival of Unleavened Bread (which includes Passover), the Festival of Weeks (or Harvest or Pentecost) and the Festival of Tabernacles (or Booths or Ingathering). See the article “Festivals.” Under normal circumstances, the roads would be filled with pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem during these times. They were occasions for joy and celebration. In troubled times, few would take the risk, and now there is no city or temple to come to. The phrase indicates the city has ceased to function.

1:8 unclean. See note on Lev 21:1; see also the article “Unclean Food.”

1:15 winepress. It accommodated a load of grapes as well as space for the persons who would tread the juice out of the grapes with bare feet. The juice would flow through a drain channel into large earthen jars, where it would ferment into wine. The fact that wine making was such a common and visible part of the culture provided speakers and writers with rich metaphors their audience would easily understand. While the winepress provides a number of positive metaphors, here the emphasis is on the trampling and crushing aspects.

2:1 footstool. In Assyrian sources the imagery of establishing a royal throne and footstool in a city-state represents the sovereign’s presence and authority (see Ps 99:5). In Ps 132:7 it refers to the temple. In 1Ch 28:2 it is used in parallel with the ark of the covenant. In this text Yahweh has withdrawn his presence (see note on Eze 10:18; see also the article “Esarhaddon’s Inscription Concerning Babylon”).

2:3 right hand. See note on Ps 16:8.

2:6 dwelling. The Hebrew word refers not to a substantial shelter (cf. Jnh 4:5) but to a hut intended for temporary cover. The same imagery is used in the early second-millennium BC “Lament Over the Destruction of Ur,” where the speaker laments that his sturdy and righteous house has caved in as if it were a garden hut.

2:8 wall. The city wall itself provided a barrier from the enemy as well as a protected platform from which the city’s defenders could fire on the enemy. measuring line. Used to determine the area of land holdings, where boundaries were drawn, and what territory belonged to which landholder (private or city)—but none of these explain the connection to the walls and ramparts in this verse. From the use of this metaphor in 2Ki 21:13 and Isa 34:11, it can be assumed that it represents a typical action connected with military conquest. A besieging army would not have the leisure to do such measuring during the battle, so this must refer to the demolition phase. It was rare for city walls to be totally demolished, and from Nehemiah we know that Jerusalem’s wall was not totally demolished. However, many sections of the wall may suffer damage due to siege machines, battering rams and sapping operations. Plumb lines would have been used to help determine segments of wall that were no longer stable, and the measuring line would have been used to delineate how much of which sections would need to come down. ramparts. A rampart or outer wall served to protect the main city wall from threat of battering rams and to impede a frontal assault. In some cases, the rampart may be nothing more than a mound raised to encircle the city. It may be faced with a stone glacis.

2:11 eyes fail from weeping. The imagery the poet uses here is consistent with that used elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible and pervasively in literature from neighboring cultures. Emotions were commonly understood psychosomatically, as integral to the person. Distressing situations were understood to have physical implications as well as emotional impact. At its core, distress impacts the gut (meeh, “intestines”; NIV “within”) and kabed (“liver”; NIV “heart”) and then expresses itself through the eyes, which flow with tears. And as the tears flow, vision is impaired—the eyes “fail”—and one’s strength flows out.

2:15 clap their hands. Gestures and body language take on different meanings in different cultures. In current Western society, clapping hands can be used to show appreciation, to summon subordinates or children, to get someone’s attention, to accompany music or to express frustration (one clap). There were also several functions in the ancient world. Clapping could be used in praise (Ps 47:1) or applause (2Ki 11:12), but in this verse a different verb is used. The verb used here designates a gesture of anger or derision (cf. Nu 24:10 [“struck . . . together”]; Job 27:23 [“claps . . . in derision”]). Variations may exist in the precise movement involved: compare the different significations in Western culture of (1) striking the palms together parallel to the body on a horizontal plain (applause); (2) slapping the palms together in a roughly vertical movement (frustration); and (3) striking the palms together perpendicular to the body while alternating which hand is on top and which is on bottom (as if knocking the dust off). It is unclear precisely what motion is conveyed here.

2:19 watches of the night. Hebrew reckoning of time divided the night into three four-hour “watches”: first watch, middle watch and morning watch. These would be determined by observing the position of circumpolar stars.

2:20 women eat their offspring. Cannibalism is a standard element of curses in Assyrian treaties of the seventh century BC. It was the last resort in times of impending starvation. This level of desperation could occur in times of severe famine (as illustrated in the Atrahasis epic) or could be the result of siege (as during Ashurbanipal’s siege of Babylon, about 650 BC) when the food supply had become depleted, as anticipated in the treaty texts. Siege warfare was common in the ancient world, so this may not have been as rare an occasion as might be presumed (see the article “Siege Warfare”).

3:15 bitter herbs. This Hebrew word occurs elsewhere only in the Passover passages. gall. Wormwood; it is a bitter-tasting shrub used for medicinal purposes and also occasionally to brew a strong tea. Both “bitter herbs” and “gall” serve here as a metaphor for bitterness.

3:16 broken my teeth with gravel. The second phrase of the verse suggests that the teeth were broken by shoving the face hard into the gravel rather than forcing someone to chew gravel.

3:27 yoke. The term is used in both Hebrew and other texts from the ancient Near East to refer to the beam apparatus that hitched two animals together to pull a plow or vehicle and as a metaphor for submission.

3:34 crush underfoot. See note on 2:1. Ps 68:21 presents Israel’s victorious, sovereign Lord as one who will “crush the heads of his enemies.” The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin depicts the enemy being crushed underfoot. Amenhotep II is depicted with his enemies underfoot. A pair of Tutankhamun’s sandals found in his tomb depict a pair of bound enemies—one Asiatic, one Nubian—on the insole, providing opportunity to continually “crush underfoot” his enemies.

3:48–49 tears flow from my eyes . . . My eyes will flow. See note on 2:11.

3:53 pit. The Hebrew term here is the common word for cistern. Cisterns were particularly significant in the mountainous topography and semiarid climate of the region of Judah (see note on Jer 38:6). Water was at a premium. Great effort was made to conserve rain water and run-off. The “first audience” of these poems would have a mental picture of pits carved into the limestone of the Judahite mountains. The interiors of their cisterns were plastered over to prevent water loss. A stone lid was placed over the opening to prevent debris from entering the cistern and to inhibit evaporation. Having one’s own cistern was a source of security and a sign of independence. However, cisterns were not always full of water. When not maintained or in times of drought their contents turned to mud and slime. Officials of King Zedekiah’s court pursue their stated intent to put Jeremiah to death by lowering him into an unused cistern. There he was left to die of starvation and hypothermia. By extension, “going down into the pit (cistern)” became a euphemism for “death.” Jeremiah reports that at least on occasion cisterns proved to be convenient places to stash cadavers. stones. The Hebrew word is singular (“stone”). The NIV translators interpret the term as a collective noun indicating that death by stoning was attempted. In the setting, however, the “first audience” may have pictured the stone lid being placed over the cistern, sealing in the captives and leading to a slimy, cold death by hypothermia.

4:3 ostriches. There is still controversy over whether “ostriches” is the proper translation of this Hebrew word. Ostriches occur in hunting scenes in Egyptian paintings as well as on cylinder seals, and they inhabited many regions of the ancient Near East. The alternative translation preferred by some is “eagle-owl.” The ostrich identification would correspond with the inattention to the young attributed to the ostrich (a different Hebrew word) in Job 39:13–16. Casual observation could make the ostrich appear heartless since it lays its eggs in the sand and often leaves the nest to hunt for food.

4:5 purple. Or “scarlet” (Hebrew tola rather than the more commonly used argaman). Tola refers to the color produced by dye made from the insect Kermes ilicis (formerly known as Coccus ilicis) rather than to the color derived from the murex snail. Its use was restricted to the ceremonial garments of only the highest ranking civil and religious leaders.

4:8–10 The siege Nebuchadnezzar laid against Jerusalem (2Ki 25:1–3) lasted a year and a half. Siege was one of the tactics used in the ancient Near East to subdue a city (see the article “Siege Warfare”). The population was cut off from the source of their food until their resistance broke. The Arameans used this tactic against Israel’s capital city, Samaria. The severity of the famine coupled with the resolute resistance of the besieged occasioned some in the population to resort to cannibalism (see note on Jer 19:9).

4:17 looking in vain for help. When Nebuchadnezzar undertook his punitive raid against Jerusalem in 597 BC, Egypt was the principal ally on whom Judah relied. Later that year, Nebuchadnezzar put Zedekiah on the throne. Zedekiah almost immediately began meeting with a coalition of the small western states to stand together against Nebuchadnezzar (see note on Jer 27:3). In 595 BC, a new pharaoh, Psammetichus II, took the throne of Egypt. He enjoyed an early military success against the Nubians in the south, and one papyrus reports that his success was celebrated with a victory tour in Palestine. There was cause to expect his support against Babylon. It is uncertain which nations were actually part of the alliance when it finally took shape. As it turned out, Egypt’s army was routed in their confrontation with the Babylonians in 588 BC (see Jer 37:5–7), and it would appear, based on Ps 137:7, that allies such as the Edomites threw their support to Babylon when it became clear that Jerusalem was about to fall.

4:19 mountains. From the perspective of the people of Judah, especially those of Jerusalem, the Judahite mountains represented a measure of security. Up to this time, the great battlefields of history were either down along the coastal plain and broad valleys of the foothills or up north in the Jezreel Valley and the Beth Shan Valley. If the enemy did ascend into the mountains, the central Benjamin plateau, about 5 miles (8 kilometers) north of Jerusalem, provided a suitable battlefield. But rugged terrain around Jerusalem was hard for invading armies to negotiate. desert. The Desert of Judah was harder than even the mountains were for invading armies to negotiate. This was where David fled for refuge from Saul. But the poet’s point is that these natural defenses were inadequate this time.

4:20 The LORD’s anointed, our very life breath. The poet refers here to the Davidic king who ideally reigned under Yahweh, Israel’s ultimate and proper sovereign. In Israel, while the king represented authority, administered justice, exercised mercy, and provided protection, he was always subject to Yahweh. There is indication in the larger culture of the ancient Near East that the king is god incarnate. By the time of the pyramids, the Egyptian pharaoh was referred to as god. The divine king was seen as the one on whom subjects depended for life and livelihood. Sesostris III (c.1878–1843 BC) is referred to as “he who gives breath to his subjects.” Early Mesopotamian texts use similar expressions. The poet here expresses that the promised and anointed king, the representative of Yahweh—Israel’s breath of life—had been taken away. under his shadow. The Hebrews perceived Yahweh as Protector and often used the metaphor of shadow (see note on Ps 91:1) or shade (Ps 121:5). Similarly, both Egyptian and Mesopotamian texts refer to the king/god as a “shadow,” implying protector. In the Report of Wenamun, describing an Egyptian official’s trip to Byblos in what is now Lebanon, it is claimed for Wenamun that “the shadow of Pharaoh [referring to the Phoenician prince]—life, prosperity, health!—your lord has fallen on you!” What these disparate cultures share in common is a connection between the concept of king and the concept of deity and the notion that God/king is the source of life and security.

4:21 Edom. See note on Jer 49:7. Edom had become an Assyrian vassal state in the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III and continued under their rule until the death of Ashurbanipal a century later. It is likely that they submitted themselves to Nebuchadnezzar’s rule in 605 BC. Although some Judahite refugees may have found shelter in Edom, they apparently remained passive as Jerusalem was destroyed (see Ps 137:7; Ob 11). The Babylonian campaign against Ammon and Moab in 594 BC seems not to have affected Edom. It is likely that they remained unscathed until the time of Nabonidus’s campaign in 552 BC. Uz. The homeland of Job (Job 1:1); it is identified with Edom and northwest Arabia in Esau’s genealogy (Ge 36:28).

5:2 Our inheritance has been turned over to strangers. The poet laments the loss of this inheritance, an external indication of the breakdown of the covenant relationship. Inheritance and property rights were significant issues in the ancient Near East, but they were especially important in Israel (see the article “Land Grants”). The significance of property and inheritance rights in the ancient Near East is illustrated by the Vassal Treaties of Esarhaddon, which include among its curses: “May your sons not have authority over your house, but a foreign enemy divide your possessions.”

5:6 submitted. Lit. “gave hand,” which has sometimes been idiomatically rendered “shook hands,” but more likely refers to a gesture formalizing surrender to foreign sovereignty. The Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, e.g., is pictured on a throne dais, dressed in royal attire, shaking hands with Marduk-zakir-shumi mentioned in the text inscribed on the dais. In one of the Amarna letters, Yapahu, prince of Gezer, complains that his brother has “given his two hands to the chief of the ‘Apiru.’ And now the [land of . . . ] anna is hostile to me.” The implication is that Yapahu’s brother has made an alliance with the enemy. In Hezekiah’s call to Israel and Judah to return to Yahweh and celebrate the Passover, he calls on the people to renew their allegiance, lit. “give a hand” (NIV “submit”), to Yahweh (2Ch 30:8). Egypt and Assyria. From the beginning of the seventh century BC, Judah had been under Assyrian control. Manasseh was a loyal vassal for most of his 55 years. During the time of Josiah, Judah experienced a glimpse of independence as the mantle was shifting from Assyria to Babylon. During that interim, Egypt began to exercise more control in the region. Jehoiakim, the son of Josiah, had been put on the throne by the Egyptians in 609 BC, and he remained loyal to them until Nebuchadnezzar’s domination made that impossible. After the fall of Ashkelon to Nebuchadnezzar in 604, Jehoiakim paid tribute to Babylon for a few years. But when Nebuchadnezzar failed in his attempted invasion of Egypt in 601, Jehoiakim again sided with Egypt and stopped sending the yearly tribute east. Thus, in 597 when Nebuchadnezzar undertook his punitive raid against Jerusalem, Egypt was the principal ally on whom Judah relied. It can fairly be said, then, that Judah had been totally dependent on Egypt and Assyria—and that reliance went back a century or more.

5:7 Our ancestors sinned . . . we bear their punishment. The idea that the poet and his generation bore some measure of guilt previously incurred by their forebears is based on the covenant stipulation, “I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me” (Ex 20:5; Dt 5:9; cf. Ex 34:7; Nu 14:18, 33). It is reflected in the proverbial “sour grapes” saying (see Jer 31:29; Eze 18:2 and notes), albeit from a different perspective. It is important to note, however, that the poet understands that the cause of the calamity is also the result of his own sin and that of his contemporaries (1:20a).

5:12 Princes have been hung up by their hands. The Hebrew text is ambiguous regarding whether the princes are hung at the hands of the enemy or are hung suspended from their own hands. There is no precedent for the latter. hung. Generally done after execution had taken place. Victims were usually “hung” by being impaled. The practice was most commonly used on rebellion leaders or members of the royal house (1Sa 31:10). The practice of impaling the bodies of their defeated enemies was commonly used by armies in the ancient Near East. The Assyrians, e.g., considered it a psychological ploy and a terror tactic (as depicted on the walls of their royal palaces). See note on Est 2:23.

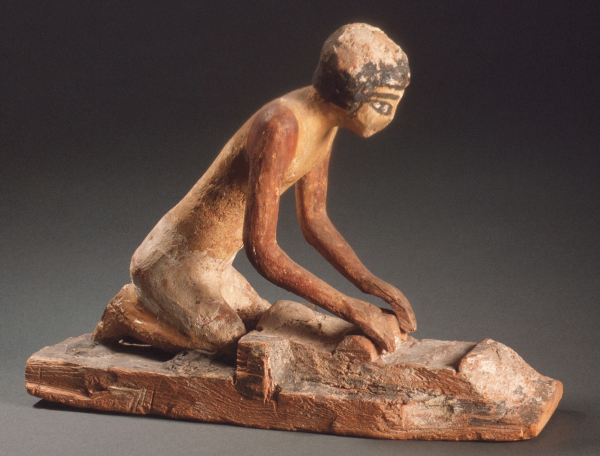

5:13 toil at the millstones. Grinding grain into flour was usually done with millstones and was the job of the lowest members of society. One of the basic “appliances” of any ancient household would have been the hand mill (called a saddle quern), which had two stones for grinding: a lower stone with a concave surface and a loaf-shaped upper stone. The daily chore of grinding grain into flour involved sliding the upper stone over the grain spread on the lower stone. Larger milling houses often served as prison workhouses in Mesopotamia, but each prisoner still used a hand mill for grinding. The palace at Ebla had a room containing 16 hand mills inferred to be a place where prisoners ground grain. Grinding houses used prisoners of war, criminals and those who had defaulted on their debts. loads of wood. Wood was a constant necessity for keeping the fires of the kitchens supplied. The palace, temple and upper class employed the services of slave labor to man the system. Even children were capable of helping transport and distribute the wood.

5:16 crown. Crowns are worn by royalty as a symbol of their status and authority. As a result, the word was extended to refer to the abstract concept of the dignity and honor that are the natural accompaniments of status and authority. In this passage the reference is not to an actual crown that Israel wore but to the dignity and honor.

5:21 Restore us. At or near the end of each of the classic Mesopotamian city laments an appeal for restoration is made to deity (see the article “City Laments”). In the various laments the appeal is voiced either by the citizens or by a lower-level deity. The Ur lament includes a brief appeal to “undo the sins”; it also requests, “May every heart of its people be pure before thee! May the heart of those who dwell in the land be good before thee!” On the other hand, the laments over Sumer and Ur and over Eridu do not include this sort of confession/petition.