Annotations for Hosea

1:1 during the reigns of Uzziah . . . Jeroboam. Hosea prophesied from as early as the time of the Israelite king Jeroboam II (786–745 BC) to as late as the reign of the Judahite king Hezekiah (725–686 BC; 715–687 BC as sole king). His prophetic ministry thus lasted 20–45 years. Most if not all of it took place before the conquest of Samaria by the Assyrians in 722 BC. It is odd that a book about a prophet from the northern kingdom of Israel ministering within the kingdom of Israel begins by mentioning the kings of Judah prior to the king of Israel. This suggests that the message of the book in its final form was directed primarily to the southern kingdom of Judah and at a later period when Hosea’s preaching had become famous for its divine authority and abiding relevancy.

1:2 Go, marry a promiscuous woman. The following background information serves to supplement the debates found in other commentaries, including whether Gomer was promiscuous before (as is more likely), or only after, her marriage to Hosea. First, the Hebrew word rendered by the NIV as “promiscuous” is not a technical term for a prostitute; it is rather a general term describing the promiscuous sexual behavior of a woman who is either betrothed or married. Its scope of meaning can nonetheless include the sexual behavior of a prostitute as well (see Na 3:4, where both “wanton lust” and “prostitution” translate the same Hebrew word). Regarding the possibility of her involvement in prostitution, we must rule out for lack of evidence any notion that Hosea’s wife was likely involved in what is normally meant by “sacred prostitution”—i.e., prostitution at a temple where the sex act was done imitatively to conjure up fertility among the gods. Second, the Hebrew syntax of the phrase in which “promiscuous” occurs can (and usually does) describe the present behavior of the woman, thereby favoring the notion that Gomer was promiscuous at the time Hosea married her. Thirdly, the Hebrew directive draws especial attention to the implications of the command for the person who receives the command, suggesting in this case that the Lord knew that he was asking Hosea to do something ominous, at personal cost. And finally, assuming, as we should, that Hosea was asked to marry an unchaste person, one remaining moral issue is certain: given the great moral offense that would otherwise apply to Gomer’s first husband, Hosea married a woman whose husband was no longer on the scene. Gomer was thus likely a prostitute, or else a promiscuous divorcee or widow. And since the legitimacy of Gomer’s children pre-Hosea is questioned (see next segment of this note) she was most likely a prostitute. and have children with her. Other translations (NASB, KJV, NKJV) carry the sense that Hosea is being asked to take Gomer’s children, born before her marriage to Hosea, and adopt them as his own. In support of this idea, in 2:1 the three “sign-children” (two boys and a girl) are told to speak to their “sisters” (note the plural) as well as to their “brothers.” A face-value reading of these plurals suggests that Jezreel, Lo-Ruhamah and Lo-Ammi were recent additions to what we today would call a blended family. It is doubtful that Hosea intended us to explore the situation of Gomer’s older children beyond the significance attached to their names. In their real lives, however, these children had more than their names to distance them from their father. In Mesopotamia and Israel, inheritance of property, as well as one’s status in society, were normally passed on from father to son. A child’s uncertain paternity could disqualify him or her for these vital benefits. Hosea implies that the same dubious status applies to the Israelites in relation to God their Father. Owing to their mother’s wantonness, any children Gomer had before marrying Hosea, as well as Lo-Ruhamah and Lo-Ammi who came later, faced financial insecurity and deprivation of inheritance rights were Hosea to have pressed the issue.

1:4 Jezreel. The name has significance, as does the location it denotes. Jezreel can mean both “God scatters” (with negative connotations) and “God sows” (with positive connotations, including the bestowal of fertility). The wordplay also worked because, even more than in English, the Hebrew word “Jezreel” sounds much like “Israel” and was thus used by Hosea to denote Israel (2:22). The town of Jezreel (modern-day Zer’in), a secondary capital of Israel, was the site for the overzealous coup d’état of Jehu in which Joram, Jezebel, all of Ahab’s sons, and also Ahaziah king of Judah were assassinated (2Ki 9–10).

2:2 she is not my wife, and I am not her husband. Several ancient Near Eastern parallels indicate that Hosea is here alluding to the legal language of an actual statement of divorce. According to Mesopotamian cuneiform sources, a person effected a divorce by saying, “You are not my wife.” Similarly, within the Egyptian Jewish community of the fifth century BC on the island of Elephantine, a husband or wife could make a statement in repudiation of the marriage by standing up in a congregation and saying, “I hated [personal name], my husband/wife.” Likely excepting when there were solid grounds for the divorce, such as adultery, the dismissing party would be obligated to pay the other “money of hatred” (which varied from a modest to a fair sum). The dowry in such a case always reverted to the wife. Moreover, the wife was entitled to go wherever she desired, including back to the home of her father. Such practices are attested widely in the ancient world.

2:3 strip her naked. Several documents, including wills that were found in the town of Nuzi, refer to this type of treatment of a wife who abandons her husband to live with another man. It is typically the children who perform this legal act. It is intended to humiliate and perhaps served as an instrument of divorce, though in cases where the husband has already died, it is related to property rights.

2:5, 8 Both the Code of Hammurapi and the Middle Assyrian Laws contain lists of items that a husband must by law supply his wife for her daily maintenance. These include grain, oil, wool and clothing. These staples formed the basis of the economy of the ancient Near East and were the symbols of fertility granted to the people by God (Jer 31:12). Thus, within the marriage metaphor employed by Hosea, the providing of these items represented God’s fulfillment of the covenant agreement. However, Israel’s choice is to take “lovers” (i.e., other gods), worship them and give them presents of gold and silver instead of acknowledging Yahweh’s gifts (cf. Eze 16:13–19). Israel credited the fertility gods such as Baal for the provision of these needs.

2:12 vines and . . . fig trees . . . her pay from her lovers. The Egyptian “Love Songs” of Papyrus Harris 500 mention the giving of a jug of sweet mandrake wine as a lover’s present. Such gifts would have been common as an expression of endearment or affection, but the term for payment here is the one used to mean the fee of a prostitute rather than the offering to a lover. This draws the metaphor of Israel/Gomer’s infidelity back into focus. The use of vines and fig trees also strikes at another source of wealth and festivity in ancient Israel. There could be no celebration without these important products that were harvested in August and September. wild animals will devour them. The eighth-century BC Aramaic inscription from Deir ‘Alla that contains the prophecy of Balaam and the twentieth-century BC Egyptian Prophecies of Neferti both describe an abandoned land in which strange and ravenous animals forage for food. Ravaging wild beasts were considered one of the typical scourges that a deity would send as punishment. As early as the Gilgamesh Epic in Mesopotamia, the god Ea had reprimanded Enlil for using something as dramatic as a flood rather than sending lions to ravage the people. The gods used wild beasts along with disease, drought and famine to reduce the human population. A common threat connected to negative omens in the Assyrian period was that lions and wolves would rage through the land. In like manner devastation by wild animals was one of the curses invoked for treaty violation. The image here is one of the chaos that results when civilization falls apart (see Dt 32:23–25 for an example of God cursing the land and its produce).

2:15 Valley of Achor. When Achan violated the ban during the capture of Jericho, he and his entire family were stoned to death in what came to be known as the Valley of Achor (Jos 7:25–26). The site is located on Judah’s northern tribal border (Jos 15:7), modern El Buquê‘ah. Hosea’s mention of the “Valley of Trouble” (see NIV text note) is an attempt to demonstrate that if even such an ill-fated place can be transformed, then so can Gomer/Israel’s relationship with Hosea/Yahweh.

2:19 I will betroth you in righteousness and justice. It is best to follow the NIV text note, which renders the Hebrew preposition as “with” instead of “in.” The just, righteous and loving attributes of God are thus a (re-)betrothal gift. This must be a re-betrothal and not a flashback to Hosea’s first occasion of marriage. This is because according to ancient Near Eastern custom, were this the first time of marriage for the bride, the gifts would have gone to the father of the bride (see the article “Marriage Contracts”). In the case of a widow or divorcee who didn’t live at home (which one can well imagine applied in the case of Gomer), this gift would go directly to the bride, as we see here.

3:1 sacred raisin cakes. See note on Jer 44:19 for the offering of sweet cakes (made from figs or dates) to the gods of Mesopotamia. There is some uncertainty in translating the Hebrew word here. Some commentators suggest that jars of wine are meant rather than compressed cakes of grapes or raisins. In either case, it is the produce of the grape harvest that is being used as an offering.

3:2 bought her. Given the value of the barley added to the 15 shekels of silver, one estimate would make Hosea’s total outlay approximately 30 shekels. This amount is equal to the amount due as compensation for the loss of a slave in Ex 21:32. Since Gomer’s situation is unclear, it is not possible to make a definite determination of why Hosea would pay out this amount. Based on Middle Assyrian Laws, however, he may be redeeming her from a legal situation from which she could not extricate herself (such as paying a debt she owed). fifteen shekels. About six ounces (170 grams). a homer and a lethek. Possibly weighed about 430 pounds (195 kilograms).

3:4 sacred stones. See notes on 1Ki 14:23; Jer 43:13. ephod. See note on 1Sa 2:18. household gods. See the article “Household Gods.”

4:3 Because of this the land dries up. Ugaritic texts serve to illustrate a belief within the culture of a connection between the welfare of an important individual, such as the king, and the welfare of the land. The occasion that precipitated El’s order to inspect the land for evidence of a drought was a physical illness on the part of King Kirta. Israelites in Hosea’s day may similarly have thought there to be a link between the moral failures of figures like the king, princes and priests and various problems that affected the land and its creatures.

4:12 wooden idol. Although it is possible that Hosea is referring to the practice of rhabdomancy (divining the will of the gods by casting rods or wands; see note on Isa 2:6 for a variety of forms of divination), this is more likely a reference to sacred groves or Asherah poles (see notes on Dt 7:5; 1Ki 14:23). Idols were often carved from wood (Jer 10:3–5; Hab 2:18–19), and this practice was so common in Mesopotamia that Sumerian texts refer to certain types of wood as the “flesh of the gods.”

4:13 They sacrifice on the mountaintops . . . on the hills. See notes on 1Ki 3:2; 11:7; 2Ch 1:3. under oak, poplar and terebinth. See notes on Ge 12:6; Dt 12:2.

4:14 shrine prostitutes. See notes on Ge 38:15; Dt 23:17–18.

4:15 Beth Aven. See NIV text note.

5:1 snare . . . net. See notes on Ps 124:7; 140:5.

5:7 New Moon. While Hosea may be referring once again to the New Moon festivals that had become corrupted by Baal worship (see 2:11), the term used here can simply mean the arrival of a new month in the cycle of the lunar year. See notes on Nu 28:11; 1Sa 20:5; 2Ki 4:23.

5:8 Gibeah . . . Ramah . . . Beth Aven. There is an allusion here to a military confrontation between the northern and southern kingdoms (Ephraim and Judah, respectively) concerning the border between the two. The reference to the three cities in Benjamin (Gibeah = Jeba‘; Ramah = Er-Ram; Beth Aven = Khirbet el-‘Askar) suggests either that they are being invaded by Ephraim (perhaps the beginning of an attack on Jerusalem), or that their men are being called to battle by Judah (perhaps to invade Ephraim). Each of these sites guards the northern track to Judah’s capital. The alarm being raised is most likely associated with a phase of the Syro-Ephraimite War of the 730s BC (see the article “Syro-Ephraimite War”).

5:10 move boundary stones. See note on Dt 19:14.

5:13 Ephraim turned to Assyria. The destructive effects of the Syro-Ephraimite War will leave both Israel (Ephraim) and Judah exhausted and even more vulnerable to the political hegemony of the Assyrians. Realizing that their status as vassals was deteriorating, two Israelite kings—Menahem in 738 BC (2Ki 15:19–20) and later Hoshea in 732 BC (2Ki 17:3)—were forced to pay large sums to keep the Assyrians from further ravaging their country. The Assyrian annals of Tiglath-Pileser III record these tribute payments, along with those of many other small nations, being economically drained by the empire’s need for funds. great king. The NIV differs from the Hebrew text, which reads “king (of) Yareb.” It differs because there is no known king or place with this name and because the word order is backward for a king’s name. The NIV option, differing only with the traditional vocalization of the Hebrew letters and not the letters themselves, arises because the expression occurs in parallelism with “the king of Assyria.” Moreover, “great king” finds warrant from the Assyrian language itself, which has an expression sharru rabu, meaning “great king,” which, when translated into the Hebrew language, would have consonants similar to what we have here in the Hebrew text. The interpretation of the NIV finds support from an Aramaic text that similarly transfers this common Assyrian expression into its own language.

6:3 winter rains . . . spring rains. Based on the Mediterranean climate of the Middle East, Israel receives its rain twice during the year. The “winter” rains fall from December to February. As noted in the tenth-century BC Gezer calendar, this moisture softens the earth and prepares it for plowing and sowing of wheat, barley and oats. The “spring” rains come during March and April and provide the life-giving water needed for the sowing of millet and vegetable crops. It is the timing of these rains that makes the difference between a good harvest and famine. Tying Yahweh to the rains supersedes Baal’s role as the rain and fertility god, and tying Yahweh to the sun supersedes the sun-gods who were often associated with justice.

6:7 Adam. Rather than a reference to the first man, here “Adam” is best understood as a place-name. This provides a better match with the word “there” later in the verse and also with the place-name Gilead in v. 8. Pharaoh Shishak’s inscription, recorded in the temple of Amun in Karnak, mentions Adam; it was the first place Shishak captured on his way across the Jordan River to overpower King Jeroboam of Israel in the tenth century BC. Mentioned also in Jos 3:16, it is located on the east side of the Jordan River a short distance south of the point where the Jabbok River meets the Jordan River.

6:8–9 Gilead . . . stained with . . . blood . . . murder on the road to Shechem. The event chronicled here may be Pekah’s rebellion against the Israelite king Pekahiah in 736 BC (2Ki 15:25). Apparently the fighting began at Adam, with the aid of a group of Gileadites, and spread west along the Wadi Farah road into Israel as far as the city of Shechem. Apparently, Pekah’s supporters were aided by priests from Bethel in their efforts to eliminate the king’s officials.

7:4–8 In the light of the tumultuous nature of Israel’s political scene in the 730s BC, these baking metaphors are quite apt. The oven depicted here was made of clay and was cylindrical in shape. Examples of this device have been excavated at Taanach and Megiddo. It may have been embedded into the floor or lay on it. The domed roof had a large hole covered by a door, through which the baker would first add fuel (wood, dried grass, dung, or cakes made from olive residue). Flames would escape through the hole until a hot bed of coals remained. The heat would be captured as the door was closed and would remain for many hours (enough for the bread to be kneaded and allowed to rise). Then the baker would place the slightly raised flat bread on the inner walls of the oven or amongst the coals. The metaphor plays on these mundane tasks and well-known images. The rebel forces of Pekah, fiercely “flamed” within the oven of Israel’s political affairs, destroyed Pekahiah’s regime in 735 BC. The resentment caused by this action smoldered as an oven holding its heat and waiting to burn those in charge. Then in 732 BC Hoshea assassinated Pekah and immediately reversed Israel’s political alliances (2Ki 15:30), shifting to Assyria for help and then three years later once again seeking an Egyptian alliance (Hos 7:11). This muddled policy left Israel “half-baked,” like a loaf left on the wall of the oven that had never been turned. It was burnt on one side and doughy on the other.

7:11 Ephraim is like a dove. The vacillating political policy of the kings of Israel is compared to the gullibility (cf. Pr 14:15) of doves who are an easy prey for the fowler’s net. In addition, the dove’s lack of concern over lost chicks may be compared to Israel’s political amnesia with regard to Assyrian policies (see Hos 5:13). Egypt . . . Assyria. Throughout much of his brief reign, Pekah practiced an anti-Assyrian policy and sought aid from the Egyptians. This had led to the campaign of Tiglath-Pileser III described in 2Ki 15:29 that resulted in the capture of much of the Galilee region and a deportation of Israelites to Assyria. Once Hoshea came to the throne, he initially paid tribute to the Assyrians, but then sent envoys to Egypt. Such duplicity enraged the Assyrian king Shalmaneser V, and he besieged Samaria for three years. His successor, Sargon II, then took the city in 721 BC and deported much of the Israelite population.

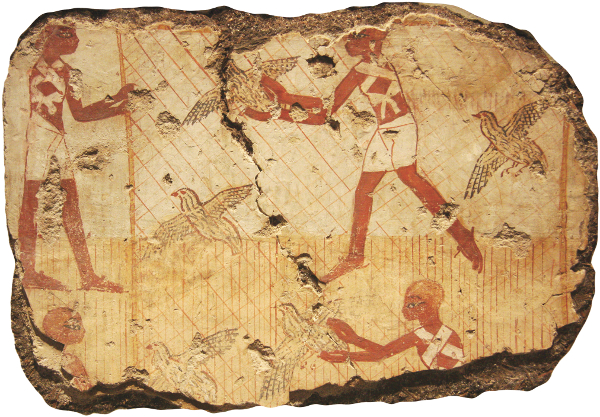

7:12 throw my net over . . . the birds. There were a number of different techniques used to snare birds. Although hunters might simply use a sling, a throwing stick or a bow to take down individual fowl, the majority of instances in the Bible and in ancient art depict large flocks of birds being captured in nets or cages. The tomb of Kagemmi at Saqqarah (Sixth Dynasty Egypt) portrays the fowler using a net. Apparently some fowlers also used decoys, along with bait food, in their snares to attract the birds. Clearly, Israel’s kings have been snared in the net of political ambitions cast by both of the ancient superpowers, Egypt and Assyria.

7:16 faulty bow. The composite bow, made from a combination of wood, horn and animal tendons (indicated in the Ugaritic Aqhat Legend), was subject to changes in weather and humidity. If it was not kept in a case, it could lose its strength and be described as unreliable or slack (Ps 78:57). The Assyrian wisdom sayings in the Words of Ahiqar speak of the arrows of the wicked being turned back on them, and this may also be part of Hosea’s condemnation of the Israel’s leaders (see Ps 64:2–7).

8:1 trumpet. As in 5:8, the sounding of the trumpet, or ram’s horn, is a signal of approaching danger (see note on Jos 6:4). This would have set the people in motion, driving their animals into the protection of the city walls. eagle. The Hebrew can also mean “vulture.” Hosea employs an image of a bird of prey swooping down on its victim. It seems most likely that he is referring to Assyria, once again being used as a tool of God’s wrath. The hunting eagle or vulture would have been a familiar sight and they were often used in Near Eastern epic and myth, as in the Ugaritic Aqhat Legend and the Akkadian Etana myth.

8:5 calf-idol. There is ample evidence of the association of Baal worship with bovine cult images or pictures of bulls (such as the zoomorphic depiction from Tell el-Asch‘ari). King Jeroboam attempted to create his own shrines at Dan and Bethel as rivals to Jerusalem by using golden calves to serve as representations of God’s throne (see notes on 1Ki 12:28–29). Hosea now condemns the golden calves placed in these shrines as a source of false worship and a reflection of the syncretism of Baal and Yahweh worship in Israel. By Hosea’s time, only Bethel still remains, since Tiglath-Pileser III had conquered Dan in 733 BC and presumably destroyed the shrine there.

8:14 palaces. Hebrew hekal, perhaps a cognate of Akkadian egal, “big house,” may mean either temple or palace. At least during Jeroboam II’s early reign, there was an effort to build fortified cities and monumental buildings in Samaria and other major cities (cf. Judah in 2Ch 26:9–10).

9:1 prostitute at every threshing floor. One of the essential installations within the farming areas of Israel was the threshing floor, where harvested grain was brought for processing and distribution. It would also be the likely site for public gatherings (see 1Ki 22:10) and for harvest celebrations (Dt 16:13). See note on Ru 3:2.

9:4 bread of mourners. A house in mourning, having had contact with the dead, is considered unclean for seven days and must be ritually purified in order to resume normal social and religious activity (see note on Nu 19:11, 14, 16). During the period of their impurity, all their food, by extension, is equally contaminated. While it may be used to nourish their bodies, these meals are joyless and none of the food may be offered as a sacrifice to God (see Jer 16:7; Eze 24:17). This is how Hosea characterizes life in the coming exile.

9:6 Memphis. See note on Jer 2:16.

9:7 prophet . . . a maniac. There was sometimes a very fine line drawn between a person who was invested with the spirit of God (1Sa 9:6) and one who was considered to simply be insane (1Sa 21:13–15; 2Ki 9:11). In this case, however, Hosea’s enemies attempt to discredit him by claiming his prophecies are actually just the ravings of a madman (cf. Jeremiah in Jer 29:25–28 and Amos in Am 7:10).

9:9 days of Gibeah. See Jdg 19. Clearly, this story was well enough known in Hosea’s day, since he merely has to mention the name of the city to raise the specter of lawless and scandalous behavior.

9:10 grapes in the desert . . . fruit on the fig tree. There is a sense of unexpected pleasure to be found in grapes growing in the desert or ripe figs in the early part of the summer. Evidence of “grape cairns” in the Negev indicate that viticulture is possible here, and the small bunches are said to be particularly sweet. This is also the case of the small figs that ripen in May-June. They are considered such a delicacy that they are to be eaten immediately after picking (see Isa 28:4; Na 3:12). Baal Peor. See Nu 25:1–18 and notes.

9:13 children to the slayer. It is possible that this is an allusion to the political turmoil in which the leaders of Israel have embroiled the people and thus laid their families open to the rampaging Assyrian armies. The Sumerian “Lament Over the Destruction of Ur” describes similar events during times of siege where parents abandon their children. Another possibility is that the “slayer of children” is a demon. Among the Babylonian demons was Pashittu, who was considered a baby snatcher. This would be another way of referring to child exposure (see note on Eze 16:5).

9:15 wickedness in Gilgal. While Hosea’s condemnation may be based on events during the conquest period or at the time of Saul’s inauguration as king (1Sa 11:12–15), it is also possible that he is referring to a contemporary event that is not recorded elsewhere and is now unknown.

10:1 sacred stones. See notes on 1Ki 14:23; Jer 43:13.

10:4 poisonous weeds. Hebrew rosh; here it may be the veined henbane (Hyoscyamus reticulatus), which occurs in ploughed fields, especially those near steppe and desert regions. It grows to a height of two feet (60 centimeters), with hairy foliage and a yellowish, pink-veined flower. Another candidate is the Syrian scabious (Cephalaria syriaca), which has poisonous seeds. Shallow planting actually helps spread these plants since only the stalks are cut while their deep roots lie untouched (see Job 31:40).

10:5–6 the calf-idol . . . is taken from them into exile. It will be carried to Assyria as tribute. Hosea’s prediction of a Samarian calf-idol being carried away as plunder to Assyria betrays an awareness of Assyrian practice. A relief dating to the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III (744–727 BC) shows a line of Assyrians carrying away various god-statues from vanquished areas. Rhetoric found in the speech of Sennacherib’s field commander to Hezekiah at a later time suggests the Assyrians would have attributed their successful conquest to the abandonment of Israel by God (2Ki 18:19–25).

10:5 Beth Aven. See NIV text note.

10:11 trained heifer . . . to thresh . . . plow . . . break up the ground. It may be that young oxen were first trained to accept the yoke by putting them to work on the threshing floor. This relatively simple task, during which they had the opportunity of the reward of grazing (Dt 25:4), made them more docile (see Jer 50:11). Once they were able to easily receive direction, then a sledge could be added that would get the animals used to pulling a load (2Sa 24:22). This in turn prepared them for the more disciplined task of plowing a furrow in a virgin field. Ephraim is being compared to such an animal that enjoys the grazing but now will be yoked.

10:14 as Shalman devastated Beth Arbel. This apparently well-known event is unknown to modern historians. Both the individual and the place name are obscure. Shalman. Possibly refers to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser V, who could have traveled through a place called Arbel on his way to capture Samaria. Alternatively, it could refer to Shalmaneser III, who ruled Assyria a little more than a century earlier and wreaked havoc on Hazael of Damascus and then exacted tribute from King Jehu of Israel. He too could have passed through Arbel. And finally, it could refer to a Moabite king Salmanu, whose payment of tribute to Tiglath-Pileser III is recorded in Assyrian annals. Beth Arbel. There are two options on its identity: (1) Arbela on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, mentioned in 1 Maccabees 9:2 or (2) modern-day Irbid, just across the Jordan River on the south side of the Jabbok River. mothers were dashed to the ground with their children. See note on 13:16.

11:1 When Israel was a child, I loved him. Hosea’s testimony here would have provided assurance to all that God had fulfilled the parental obligation of suitable support that was a stipulation in adoptive agreements. The importance of testimony of care is well illustrated by an Old Babylonian legal case involving adoption. In that case, testimony that a child had received parental care bolstered the claim, disputed by some, that the child was indeed the adopted son of his alleged father and was thus eligible to receive his inheritance.

11:8 Admah . . . Zeboyim. These two cities, neither of which have been positively identified by archaeologists, are traditionally included with Sodom and Gomorrah as sites of utter destruction and evidence of God’s judgment (see notes on Ge 19:7; Isa 1:9).

12:1 treaty with Assyria. Like his predecessor Menahem, Hoshea was initially forced to pay tribute to the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III. The Assyrian annals even boast that when Hoshea assassinated Pekah to take the throne of Israel, the Assyrian king “placed Hoshea as king over them.” It also notes that Hoshea paid “10 talents of gold [and] 1000 (?) talents of silver” as tribute, probably to confirm his position as king in 732 BC. sends olive oil to Egypt. Shortly after Hoshea had accepted the role of Assyrian vassal king in Israel, he then shifted his allegiance by sending a large quantity of olive oil (one of Israel’s major forms of wealth) to Egypt. This would have been a valuable commodity—especially in Egypt, where olives were not grown. Playing to both superpowers and their factions, however, would soon draw Assyrian ire and lead in 722 BC to the invasion of Israel by Shalmaneser V.

12:7 merchant. The Hebrew is also translated “Canaan,” which at least evokes the idea of Canaanite influence. dishonest scales. See notes on Dt 25:13; Job 31:6; Pr 11:1. This same charge is made against unscrupulous merchants in Am 8:5. The indictment seems to be based on the idea that Israel’s economic community has been corrupted by the immoral practices of its neighbors. In an economy that did not have standardized weights and measures, traders were often tempted to cheat by falsifying the balances and measurements, often by using improper weights and false bottoms and other ways to alter the sizes of vessels.

12:10 parables. One of the ways that the prophet is able to convey God’s message is through the use of analogies or comparative stories. The parable thus can provide a dual meaning by using everyday life scenes or images and then providing an interpretation of God’s will or judgment. Cf. Nathan’s parable of the ewe lamb in 2Sa 12:1–4 (see note there).

12:11 Gilead . . . Gilgal. For Gilead’s association with Pekah’s revolt, see note on 6:8–9. For cultic activities at Gilgal, see notes on 9:15; Am 4:4–5.

12:12 Jacob fled. Hosea returns to a theme he first used at the beginning of ch. 12, drawing on the traditions about Jacob and using them to parallel the nation of Israel’s coming plight and possible redemption. So, just as the unscrupulous Jacob was forced to flee from Palestine to Harran to escape Esau’s wrath (see Ge 27–28), now Israel will once again be forced to “live in tents” (Hos 12:9). The new life and family Jacob/Israel finds in Aram, however, led him back to Palestine and served as the origin of the Israelite people.

13:2 make idols. See Isa 44:9–25 and notes; see also the note on Jer 10:3; see further the article “Making an Idol”). The acquisition and use of the skills necessary to fashion these images is simply another example, according to Hosea, of Israel’s intent to syncretize or corrupt its worship with false gods. kiss calf-idols. Kissing was the common act of submission offered to kings and gods, as attested most famously by the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, on which the Israelite king Jehu is shown kissing the ground in front of the Assyrian king. Likewise, the kissing of the idol involved kissing its feet in an act of homage, submission and allegiance. Thus, e.g., in a letter from Mari, the governor of Terqa, Kibri-Dagan, recommends that Zimri-Lim, king of Mari, proceed to Terqa in order to kiss the feet of the statue of the god Dagan/Dagon.

13:3 chaff. See note on Ps 35:5. threshing floor. See note on Ru 3:2. smoke escaping through a window. The typical Israelite pillared house had no chimney through which the smoke of the small campfire (set in the middle of the ground floor in winter) could escape. Nor is it any longer believed that there was an open courtyard above the area where the fire was. Smoke could thus escape only through an open (front) door or else through the windows, which of course had no glass. Based on depictions from ivory plaques, windows were quite narrow slits in the walls on the second story of homes (so designed for security and for keeping cool in summer and warm in winter). window. Here a different Hebrew word for window is used that denotes a window specifically for allowing smoke to escape.

13:7 lion. See notes on Jdg 14:5; Isa 31:4; Jer 5:6. leopard. The idea of the leopard as a silent, stalking hunter fits God’s role as the destroyer of the unprepared and the unvigilant Israel (see Jer 5:6). The cunning leopard appears in wisdom literature as well. There is a short fable about the leopard in the Assyrian Words of Ahiqar in which the leopard attempts to trick a goat by offering to lend the goat his coat to shelter itself from the cold. The goat escapes and calls back that the leopard was merely hoping for its hide. Leopards still inhabit some regions of Israel (En Gedi) but were not as common as lions in antiquity.

13:16 Hosea forecasts that the warfare to come will destroy the town and villages of the Israelites; not even women and children will be spared from the rampaging army as it pillages and rapes (see note on Ps 137:9). little ones . . . dashed to the ground. It would appear that this phrase actually is a standard description of warfare’s devastation. Ninth-century BC Assyrian conquest accounts speak of the burning of young boys and girls. pregnant women ripped open. This practice is mentioned very rarely. It is a practice attributed to Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I (1115–1077 BC) in a hymn praising his conquests. It is also referred to in passing in a Neo-Babylonian lament.

14:5 dew. Yahweh’s relationship with Israel is likened to the dew, which provides the only moisture available to flowers and trees during the dry months of summer (see Isa 26:19). lily. It is not common in Palestine today, though it can be found in some areas. There is dispute whether it was more common in antiquity or not. cedar of Lebanon. See note on v. 6. send down his roots. God’s life-giving essence ensures the fertility and virility of the nation so that it continues to grow and expand, like the massive root system of the olive tree (v. 6).

14:6 cedar of Lebanon. Considered the most useful of the large-growth trees in the ancient Near East. It was prized for its lumber (1Ki 6:9–10) and was a symbol of wealth in Mesopotamian literature, including the Gilgamesh Epic and the annals of many kings from the Sumerians through the Assyrians. See notes on 2Sa 5:11; 1Ki 5:6; 6:15.