Annotations for Jonah

1:2 the great city of Nineveh. See Introduction: Historical Setting.

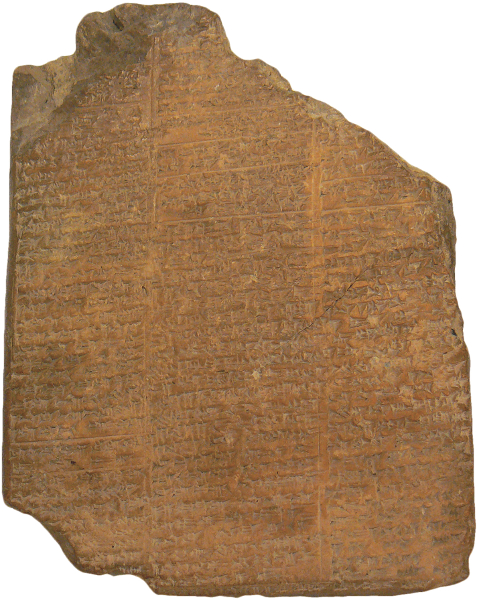

1:3 Tarshish. Some modern assessments have placed Tarshish as far west as Spain. Esarhaddon’s inscriptions refer to a Tarsisi that is west of Cyprus and Greece: “All the kings from [the islands] amidst the sea—from the country Iadnana (Cyprus), as far as Tarsisi, bowed to my feet and I received heavy tribute.” Early Christian sources associated “Tharsis” with Rhodes or Carthage. In Ge 10:4 Tarshish is listed along with Elishah and Kittim, both associated with parts of Cyprus. Though the location remains uncertain, it is used in texts to refer to the farthest known point in the west. The conflicting geographic indications in ancient texts suggest the possibility that it refers in a more general sense to far-off islands. In Solomon’s day the ships going to Tarshish would not return for three years (1Ki 10:22). Joppa. The only ports along the Mediterranean coast of Israel were Joppa, Dor and Akko. Akko was at the northern limit of Israel and was often under Phoenician control. It was little used because of the prominence of Tyre a little farther north. Situated at the southern end of modern Tel Aviv, Joppa is known from ancient and classical sources throughout the Biblical period. In the second millennium BC it is one of the targets of the Egyptian campaign of Thutmose III and is referred to as an Egyptian stronghold in the Amarna letters of the mid-fourteenth century BC. In first-millennium BC Assyrian texts it is under the control of the Philistine city of Ashkelon and is conquered by Sennacherib in 701 BC. That fact, combined with the knowledge that most sea trade at this time was carried out by the Phoenicians and Egyptians, leads us to infer that the sailors on the ship would not have been Israelites. paying the fare. Commentators remain divided on the question of whether Jonah bought passage on the ship or hired out the ship. The Hebrew term, usually referring to hire of service, favors the latter, a much more expensive proposition. Likely Jonah would have paid in silver, but no ancient sources indicate what the cost to Jonah might have been.

1:5 each cried out to his own god. Working from the inference that the sailors were likely Phoenicians, we can note that in Canaanite/Phoenician belief, though the god of the sky and storm was Hadad (often referred to by the title Baal), Yamm, the god of the sea and of chaos, would be considered the most likely candidate for bringing on such a storm (notice that Jonah identifies Yahweh as God of the sea and dry land [v. 9], not the God of the storm, suggesting he was juxtaposing Yahweh to a god such as Yamm rather than a storm-god such as Baal Hadad). Archaeological evidence suggests another god of the sea whom sailors considered their protective patron. In Esarhaddon’s treaty with Tyre, three deities are identified as patron gods of Phoenician sailors: Baal Shamem, Baal Malage and Baal Zaphon. The idea that some offense could have awakened Yamm and his sea creatures and brought the storm would be considered in the realm of possibility. Alternatively, they may have thought that someone had offended the sailor patron gods, who therefore had abandoned them to whatever Yamm wanted to do. Most people in the ancient Near East felt the closest relationship to be with their ancestral, patron or personal deities. Such deities would be the primary focus of personal worship but were not typically the cosmic deities able to send a storm such as this. Even though the sailors would not think that their personal deities had sent the storm, these are the deities to whom they might cry. Their hope would be that one of them might be able and willing to intervene on their behalf in the divine assembly and thus procure mercy. They are calling for assistance rather than crying out in repentance. The captain awakens Jonah so that Jonah might also call upon his own patron deity (v. 6). they threw the cargo into the sea. What the sailors throw overboard is most likely their supplies of food and water for the journey. If Jonah is the only passenger, there are no merchants aboard and therefore little merchandise for trade. The crew is made up of sailors, not merchants. cargo. The Hebrew word usually has to do with equipment or containers of various sorts. It can also refer to belongings (basic, such as ship stores) or possessions (jewelry). Different words are used to refer to trade goods.

1:7 cast lots. In the ancient Near East lot casting was one form of divination and was used for decision making. The process of casting lots was begun by each individual placing some identifiable marker into a container (cf. Pr 16:33, where the lot is put into a pouch above the belt). Using more specific information provided in Homer, the presumption is that the container the lots were put into was shaken up and down (as opposed to side to side) until one of the lots came out (as opposed to being drawn out by hand). In this way it can be understood that deity draws the lot out. The intention of the sailors in casting the lots was simply to get divine direction as to who could help resolve their dilemma. Thus when the lot falls on Jonah, they turn to him for information and enlightenment. Why has deity chosen him to give them understanding of their crisis? Jonah’s guilt has not yet been established—only that he possesses critical information. And so, the questioning begins.

1:9 I worship the LORD. Yahweh is often construed in Israel as possessing the authority Canaanites attributed to their gods El and Baal. Jonah’s first comment is in line with that as he identifies Yahweh as the “God of heaven.” This might even relate directly to the sailors’ patron, Baal Shamem (“Master of the Heavens”). In addition, however, Jonah informs the sailors that Yahweh is also understood to be the God who created “the sea and the dry land.” This is not the same as calling him a sea-god. Sea-gods are those who have been given jurisdiction over the sea and whose attributes are manifested in the sea. They are not considered to be the ones who created the sea. In Jonah’s confession, then, Yahweh is identified as outranking both Baal and Yamm. The sailors would understand that this was not just a standard patron deity. By v. 16 the sailors “feared the LORD,” expressing how impressed they are with the display of his power. Jonah’s confession that he fears Yahweh seems cliché or ironic in contrast, since Jonah did not fear sufficiently to obey.

1:10 he had already told them. Jonah had told them earlier that he was fleeing from his God, but that had not concerned them—that was his problem and probably not all that uncommon. Their terror now increases as they realize that Jonah’s flight from a cosmic deity has put them all in jeopardy of suffering the wrath of Jonah’s god along with him.

1:11 What should we do to you . . . ? Once Jonah’s guilt has been established and the offense and the offended deity identified with confidence, the next question logically concerns appeasement. In the thinking of the ancient world, appeasement of the deity’s anger was more important than repentance from sin, though if an offense had been identified, as here, it would have to be somehow rectified. Usually appeasement was accomplished by the performance of a specified ritual to soothe the heart of the deity. Here, however, the sailors ask not about performing a ritual for the deity but about doing something to Jonah. The major options would be (1) isolating him from them so that they would no longer be included in his fate or (2) performing an apotropaic ritual, i.e., a ritual to purify and/or protect Jonah from divine wrath.

1:12 throw me into the sea. It is interesting that Jonah chooses not only an isolation strategy but one that also would have been perceived as the most primitive of the options for appeasement. The sailors seem scandalized at what appears to be little more than human sacrifice. They attempt another strategy of isolation: rowing back to land to drop Jonah off. This is not only the more humane choice but also logical given the fact that they jettisoned their supplies and that without Jonah, they have no reason to continue the trip.

1:16 they offered a sacrifice to the LORD and made vows to him. Not all sacrifices were burnt sacrifices in the ancient world. Sailors would have had some provision on the ship for offerings to the gods during their long dangerous journey. If there were any goods left on the ship, a presentation offering of grain or a libation of oil or pure water would have been appropriate. The vows would also have pertained to offering a gift to deity, whether in silver or in grain offering, as is usually the case both in the OT and the ancient world. In the Babylonian “Hymn to Shamash,” those celebrating at wharf-side are portrayed in worship: “You are the one who saved them, surrounded by mighty waves, you accept from them in return their fine, clear libations. You drink their sweet beer and brew.” Vows were usually conditional before the fact, but they could also be appropriate as a response to an act of deliverance. Here they reflect the sailors’ gratitude at having been spared. Offering of a vow to a particular deity does not imply that other deities have been cast aside. In the polytheistic world there was ample room for unlimited numbers of deities.

1:17 huge fish. In Canaanite beliefs various sea monsters were associates of the sea-god Yamm, and sometimes they were even identified with him (see the article “Chaos Monsters”). If the sailors saw the fish, it is possible that they viewed it as a manifestation of the sea-god. No other texts in the ancient world refer to a chaos creature from the sea by the term “fish,” but creatures that live in unknown regions (desert or sea) that we know to be real animals were at times also associated with chaos creatures. At the same time, readers familiar with Biblical narratives would be aware of common creatures acting at God’s prompting (e.g., Balaam’s donkey in Nu 22:21–41 and Elijah’s ravens in 1Ki 17:2–6). three days and three nights. A person is considered truly dead after three days in the grave or netherworld. In Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld, the goddess Inanna goes down into the netherworld and tells her servant that if she has not returned in three days, she should begin to lament for her and make petitions to the gods for her return. With this idea in mind, the three days and nights in the belly of the fish in the realm of death would be an indication that Jonah was at the threshold of death.

2:2–6 In Jonah’s prayer we find reference to several components of Israel’s cosmic geography. Sheol (NIV “realm of the dead,” v. 2) is the general term for the netherworld—the abode of the dead. Tehom (NIV “deep,” v. 5) is a reference to the primordial waters of the chaos sea. The “roots of mountains” (v. 6) refer to foundations on which the world was believed to be anchored. These cosmic mountains held back the chaos waters, held up the sky, and were rooted in the netherworld. Parallel to the roots of the mountains is erets (NIV “earth,” v. 6), the normal Hebrew word for land but also used as a designation for the netherworld. Finally, shahat (NIV “pit,” v. 6) is given as yet another synonym for the netherworld. See the article “Cosmic Geography.”

2:4 banished from your sight. Being banished from the presence of deity implies disqualification from access to the sacred precincts of the temple. In general one had to maintain a certain level of ritual purity to have access to sacred precincts. Jonah’s conclusion that he had been banished would have come not from admitting that he had disobeyed but as a conclusion that death was imminent. His deliverance by the fish would have fostered the hope that he would again appear in God’s presence. It is clear from Jonah’s prayer that he views the fish as his deliverance rather than punishment. temple. The temple is mentioned both here and in v. 7 as what Jonah prays toward and what he desires access to. It raises the intriguing question of which temple he has in mind. He prays to Yahweh, who has only one legitimate temple, in Jerusalem. Yet he is a prophet from the northern kingdom of Israel, which had rejected the Jerusalem temple in favor of the golden calf shrines in Dan and Bethel. These shrines are never referred to as temples of Yahweh, though the Israelites may have regarded them as such if the calves were viewed as escorts or pedestals of Yahweh (similar to the cherubim and ark), as is sometimes claimed. Being accepted in the temple and enjoying renewed access to God’s presence would indicate being restored to favor. The context here and the offhand reference simply to the “temple” favors the Jerusalem temple as being intended.

2:6 barred me in. Jonah’s mention of bars, even if it is figurative, refers to the ancient Near Eastern idea that there are gates to the netherworld. This coincides with the ancient worldview that the netherworld was a city with walls and gates. In Ugaritic literature the city of Mot, god of the netherworld, is Hmry (“the Pit”). The OT refers to a netherworld city with gates in Job 38:17; Isa 38:10. Babylonian evidence comes from a twelfth-century BC boundary marker on which is depicted the netherworld city with tall gates guarded by a serpent-like creature. Entrance to the netherworld was typically through the grave, construed as a portal of sorts. Here Jonah views himself as having arrived at the gates of the netherworld by passing through the level of the chaos waters.

2:9 What I have vowed I will make good. For vows in general, see note on Jdg 11:30; see also the article “Nazirites.” Since that which was vowed was usually some material gift, there is little reason to think that Jonah vowed to repent of his disobedience and to willingly take up his mission to Nineveh. More likely he has vowed a gift of thanksgiving for being delivered from what seemed to be certain death.

3:3 went to Nineveh. The journey to Nineveh from Joppa (where we assume the fish left Jonah) was about 550 miles (885 kilometers). Caravans usually traveled 20–25 miles (32–40 kilometers) a day, which means Jonah made the trip in about a month. large city. The size of Nineveh is expressed in terms of the time that it would take Jonah to carry out his assignment. He is not circling the circumference of the walls but is going to all the public places in the city to make his proclamation. His itinerary would have included many of the dozen gate areas as well as several of the temple areas. There would have been certain times during the day when significant announcements could be made.

3:4 Forty more days and Nineveh will be overthrown. The prophecies of the prophets of the ancient Near East are typically ones of instruction and encouragement for the king. There is some indictment (usually cultic matters left undone) but little attestation of judgment oracles against the king who is being addressed. In the only possible exception there is an oracle against Zimri-Lim: “A devouring [plague] will take place. Issue a claim against the cities that they return the sacred things. The man who has committed violence let them expel from the city.” Occasionally a prophet will proclaim judgment on an enemy of the king, e.g., “Into the net which he ties, I will gather him. His city I will destroy, and his treasure, which is from ancient times, I will surely plunder.” In contrast, prophecies of impending judgment are common in the OT. There is no suggestion in this text that Jonah offered indictment (e.g., of their idolatry), instruction (e.g., in the law), encouragement or hope (e.g., for deliverance). The prophet’s role should not be confused with the missionary’s role. Unlike the missionary who has a message of hope (the gospel) and who comes hoping to see conversion, the prophet has whatever message God has given him and comes only to deliver it.

3:5 The Ninevites believed God. The text only indicates that the Ninevites believed the message of impending doom that Jonah had delivered. In the prophecy texts from Mari in the eighteenth century BC we get a glimpse of the authentication procedures. If the message came from an unknown prophet, something like the imprint of the hem of his/her garment was provided to the king for authentication of the prophecy. More important, the substance of the message would be confirmed by other divination procedures. In the divination procedures of the ancient Near East, which included prophecy, the practitioners preferred to have omens or messages confirmed through at least two different procedures. Omens could be read from the movement of the heavenly bodies, from the actions of animals or the flight of birds, or from the configurations of the entrails of sacrificial animals, just to name a few. Once it was determined to their satisfaction that this was a legitimate divine message, they would have accepted it and responded. It is likely that the Ninevites would have confirmed Jonah’s message in similar ways before they responded. Ninevites would not necessarily have asked why they were going to be destroyed. The literature indicates to us that in Mesopotamia they did not think that they could know the reasons or even whether there were reasons. In the “Lament Over the Destruction of Ur,” Sin, the patron deity of the city, asks why it was overthrown. The answer is given by Enlil, the head of the pantheon, that cities and dynasties were not intended to last forever, and the supremacy of Ur had run its course. Despite their acceptance of the veracity of Jonah’s message and their sincere response, they are still polytheistic Assyrians ignorant of the nature of Israel’s law, faith and God. A fast was proclaimed . . . put on sackcloth. The most relevant usage of sackcloth in an Akkadian text is in an Esarhaddon inscription in which he is said to have “wrapped his body in sackcloth befitting a penitent sinner.” See the article “Mourning.” Fasting is much more difficult to attest than use of sackcloth. While fasting is not detectable in religious rituals or for repentance in Mesopotamia, individuals did occasionally refrain from eating and drinking in mourning rites. In addition, there were special dietary instructions for certain days throughout the Babylonian year. Other occasions when the Mesopotamians did not eat or drink seem to be similar to the situation recorded in Ac 23:12, when a group of men vowed not to eat or drink until they had killed the apostle Paul. While these examples may be called fasting, there are no obvious spiritual or cultic connections to the act.

3:6 king of Nineveh. The gravest problem with the king of Assyria being called the king of Nineveh is that during the time of Jonah, the king of Assyria did not have his residence at Nineveh. Though Nineveh may have been a large and important city, it was not a royal city. Jonah would not have encountered the king of Assyria on his throne in Nineveh, because the king of Assyria did not have a throne in Nineveh. A more likely interpretation is that the “king of Nineveh” is not the king of Assyria but a governor or noble who was ruling the city/province. Concerning terminology, the Hebrew term translated “king” in Jonah (melek), though used throughout the OT for kings, does not pose an insuperable problem when we consider that an Assyrian official is being described. The normal Akkadian (Assyrian) word for king is šarru, but the bilingual Tel Fakhariyah Inscription translates the Akkadian šaknu (“governor”) with the Aramaic mlk. This suggests that West Semitic languages (Aramaic and Hebrew) could use this word to refer to local ruling governors or nobles. Furthermore, the governor (šaknu/mlk) could rule over either the city of Nineveh or the province of Nineveh. In fact, in the limmu list of Assyrian notables, the designated official for the year 761 BC was Nabu-mukin-ahi, governor of the region of Nineveh.

3:7–9 The proclamation of the king details the strategies for appeasing the angry god. Aside from the rituals of sackcloth and fasting discussed above, some behavioral changes were dictated. Though Assyrians had no revelation from their gods that would equate to Israel’s covenant law, they understood that justice was important to the gods for the order that it brought to society. Lawlessness would be offensive to the gods, so here they act to remedy that condition. It is possible that various rituals would have been performed to seek to appease God or protect them from destruction. To whatever extent such rituals may have been pursued, the text has no interest in them. God is responding to their humility and their repentance, not their rituals (which would have been attempts at manipulation).

3:8 animals be covered with sackcloth. That even animals should be adorned with the signs of repentance is not outlandish. Even today black hearses are used by funeral parlors and horses in funeral procession feature black accessories. Since sackcloth itself is not frequently attested in ancient literature, it is no surprise that we have no examples of animals being draped with it. The Apocryphal book of Judith, however, contains an example of the Jews responding in a similar way when Holofernes marched on Jerusalem (Judith 4:10–12). In addition, Herodotus notes that Persian mourning customs included cutting horses’ manes, just as people shaved their heads.

3:10 he relented. God’s action has been translated in various ways (KJV “repented”; NRSV “changed his mind”). This is one of the main passages used in discussions about whether God can change his mind. In the ancient Near East the gods were erratic and could be managed through various ritual approaches. The gods were believed to have needs, and when humans met those needs, they were attempting to soothe the god from any irritation and earn the god’s goodwill. It was therefore their desired intention to induce the god to change his mind concerning how he was treating them. This mutual dependence is the fulcrum of the Assyrian religious system. See the article “Great Symbiosis.”

When the Biblical text insists that God is not one to change his mind (Nu 23:19; 1Sa 15:29, both texts using the same verb as in Jnh 3:10), it is in the context of covenant agreements, not the outcome of prophetic pronouncements (see Jer 18:8). Mesopotamians also confirm that what their gods decree cannot be altered: “What you proclaim in the assembly, An and Enlil cannot throw out; the oracles uttered on your tongue never change in heaven or earth; / A place you sanction meets no ruin; / A place you brand does not last.” There is a distinction to be made then between ad hoc action, which could be impacted by “gifts” to the deity, and formal divine decrees, which could not be altered.

4:2 gracious and compassionate . . . slow to anger and abounding in love . . . relents. Jonah’s list of five attributes is practically creedal in the OT (Ex 34:6; Ne 9:17; Ps 86:15; Joel 2:13), so it is ironic that Jonah uses them as a basis of his complaint. The gods of the ancient Near East can be described in similar terms when maintenance of justice is at issue. In a nineteenth-century BC prayer to Utu (the sun-god), the god is described as a “righteous god who loves to preserve people alive, who hears prayer, [is] long on mercy, who knows clemency, loving justice, choosing righteousness.” In addition, prayers in the ancient Near East request the gods to be merciful (comparable to the Hebrew words translated “gracious” and “compassionate”), and they portray them as showing mercy to the afflicted. The god Gula, e.g., is described as “merciful and compassionate.” Furthermore, the gods relent when they are appeased. So, in Enuma Elish 6.137 Marduk’s fourth name identifies him as “furious but relenting.” In contrast to the situation in Israel, people in Assyria are expected to be loyal to the gods but the gods are not typically described as being loyal toward people, though prayers ask them to be. The gods are said to “love” the king, but this is an expression of preference and favor. Jonah’s list, then, does not necessarily distinguish Yahweh from how the gods of the ancient world are portrayed. The list simply represents the attributes that Jonah recognizes as assuring that his trip to Nineveh will initiate a series of inevitabilities: Jonah will give his message, Nineveh will respond (ignorantly and inadequately), God will relent.

4:8 east wind. The east wind was a problem in Palestine because of the desert to the east, but in Nineveh it would have been a very different situation. Because of the mountains east of the Tigris River running northwest to southeast, the prevailing winds in Mesopotamia are northwest and southeast. The east wind was named the mountain wind and usually brought rain. This verse specifies a particular type of east wind (“scorching”), but this Hebrew word is used only here so its nuance is obscure. It may be important to note that it is not the wind, but the sun, that is designated as the element that oppressed Jonah.

4:11 There is much discussion about the size of Nineveh’s population. For some time the number 300,000 has been cited as the estimated population of the city and its environs in the seventh century BC. Recent estimates using a variety of documents have confirmed that such a number is reasonable. If that is so, the number 120,000 for the earlier period is not exaggerated.