♦ Kyphosis – How slumping adversely affects breathing

- Your head acts like a yoke around your neck

- Slumping causes your shoulders to hang forwards

- Slumping concertinas your ribs together

- Slumping pushes your diaphragm onto your belly

♦ Posture really matters

As a trained exercise physiologist, I always return to my grounding that the most profound and constant limiting factor for human performance is gravity. Whilst it may not be obvious why gravity might have a key role in the way in which we breathe, it is the one force that is always present whatever we are doing and wherever we are, and the way our bodies react against gravity gives us our own very personal posture.

I would estimate that more than 95% of the people I meet in my clinic present with poor breathing patterns that can be directly linked to poor posture. Most of the time they have their head held in a forward position. This body position is known as ‘kyphosis’ (see Figure 3.1).

Kyphosis can be the result of one of many lifestyle issues. Lots of older patients I work with have had plenty of time to accumulate other health conditions that can have contributed to them adopting a slumped position. Some have spent so much of their retired life inactive, either slumped on a sofa or lying in bed, that they find they get stuck in that slumped rut. In western society we are becoming more and more sedentary in our work; our recreational activities are also less active than they used to be, and these are important factors that contribute to a hunched body position. Poor posture can also be an inherited trait. Have you ever noticed how families will often walk with the children showing similar movement patterns to one of their parents? Some of this may be down to nature, but some will be down to nurture, as children tend to learn by copying their parents’ movement patterns from an early age.

Figure 3.1: Kyphosis and erect posture – side view

I have coached lots of sports people, and the ones who slouch the most are the young rowers. Long levers help in rowing, so many of them are extremely tall. Being considerably taller than their peers, they may feel they have to stoop to fit in with their friends at school; some even have stoop to physically fit under a normal doorway without banging their heads. There are also skeletal conditions such as ankylosing spondilitis, scoliosis or osteoporosis, that can affect a person’s postural structure. Or it could be due to a trauma, such as a road traffic accident, that has weakened the neck. Everyone has his or her own background story that needs to be borne in mind.

I myself am not immune to the head-forwards posture, and recognise that I tend to slump when I use my laptop, tablet or mobile phone for any length of time.

Case study – watchmaker

I remember a career watchmaker in his late seventies, who had spent nearly 50 years bent over, looking at watches for more than 10 hours a day. When he came in he would have his eyes on my shoes, whether he was standing or sitting.

He was diagnosed with COPD at Level 4 on the MRC scale (see page 3), and he was also taking eight paracetamol a day for his kyphotic back pain. Three weeks after starting the programme he was down to three paracetamol a week and finding breathing much less problematic.

He put this down to the fact that he did daily exercises that forced him to be aware of his posture, and even though he was extraordinarily slumped, he got a relatively quick reduction in pain.

A month later he was totally off the painkillers and could look me in the eye. When I pointed it out to him that he could see me above my waist, he laughed and told me I wasn’t as good looking as my female colleague! That is gratitude for you.

How slumping adversely affects breathing

I have found that to help persuade my patients not to sit or stand with their heads leaning forward I need to explain how this body position can prevent them from breathing properly. Whilst not everyone sits forwards noticeably, probably 95% of my patients slump to some degree or another.

Your head acts like a yoke round your neck

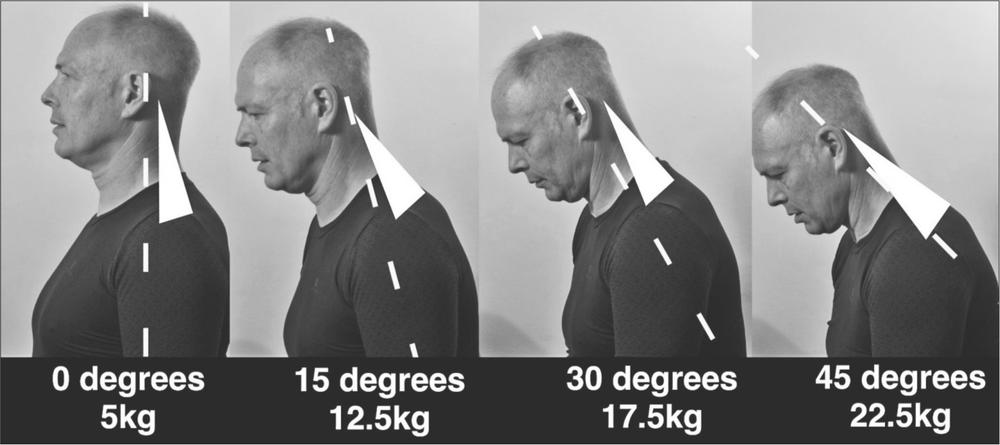

Being in kyphosis, the body has to work actively against gravity to stop the head from lolling forwards, and as a result the muscles that hold the head upright in the back of the neck have to work extra hard (see Figure 3.2). Holistic practitioners, body workers and manual therapists of all kinds look for a degree of balance and harmony in the body. When you see a person with an upright posture (see the left-hand image on the sequence in Figure 3.2), the head looks like it is balanced on top of the spine. The muscles in the neck are under approximately 5 kg of pressure, so there is little tension to make the individual feel tight or stressed. This person looks at ease.

This is in stark contrast to the slumped individual shown on the far right of Figure 3.2, where the neck and upper back muscles have to work extremely hard to prevent the head from lolling forwards.

Figure 3.2: Relative strain on neck muscles, with head forward position

I usually explain this mechanism by taking a side-on picture of my patients and comparing it to Figure 3.2. I explain how each position is like having a heavy yoke hanging round your neck, all day, every day! As the head slumps further forward the force the neck muscles have to exert increases considerably. I am quite strong, but lifting a 22.5 kg dumbbell on to the desk, and thudding it down, is very sobering. Showing patients how much strain their neck is under if they hold their head at 45 degrees from the shoulder, they tend to listen more intently to what I have to tell them next.

Additionally, if a patient adopts this body position for any length of time, it can lead to a relative shortening of the muscles at the rear of the neck as they take the strain of the weight of the head. At its most overused and extreme form, it is thought that this shortening of the neck muscles can even pinch the phrenic nerves, as they originate from between the 2nd to 6th cervical vertebrae of the spine. The phrenic nerves drive the muscular action of the diaphragm, and there is the possibility that the forward head position may inhibit the normal control of the diaphragm.

Slumping causes your shoulders to hang forwards

The head-forwards position usually results in the shoulder blades being lifted and drawn forwards around the upper ribs, hanging forward and downwards in relation to the ribcage (see Figure 3.3). This causes further loading on the postural muscles of the neck. This relentless loading compresses downwards on the rib cage, rather like the weight of the world being on your shoulders.

Figure 3.3 Slumped shoulder blades versus upright shoulder carriage

While the shoulders are hanging forwards, the small muscle groups at the front of the neck are usually simultaneously tightened and shortened. This can be to the point where the vocal chords are affected by the resulting tension in the throat and upper chest. The breath that accompanies this kyphotic body positioning is usually shallow and rapid and, with even the slightest physical demand, the limited air flow leads to an even more rapid and shorter breath.

Demonstrating the effect of shoulders hanging forwards

If you do not think that you are affected by this problem, or you have a family member who does not understand how it feels to not breathe very well, you might like to know of an exercise I teach other medics. I do this to get across the importance of posture on breathing. This is described in Figure 3.4 below.

Figure 3.4: Straitjacket demonstration

1. Imagine you are in a straitjacket, and you have people pulling your arms across your body so that your elbows cross in front of you.

2. Reach your hands as far round your back as possible, holding your shoulder blades with your fingers.

3. Breathe out as deeply as you can, readjusting your hands so that you can tightly grip your shoulder blades.

4. Maintain your hands in this position.

5. Now try and breathe in deeply!

Inevitably, when you assume this ‘straitjacket’ posture, a deep and satisfying inhalation is nigh on impossible, as the lungs have nowhere to expand into.

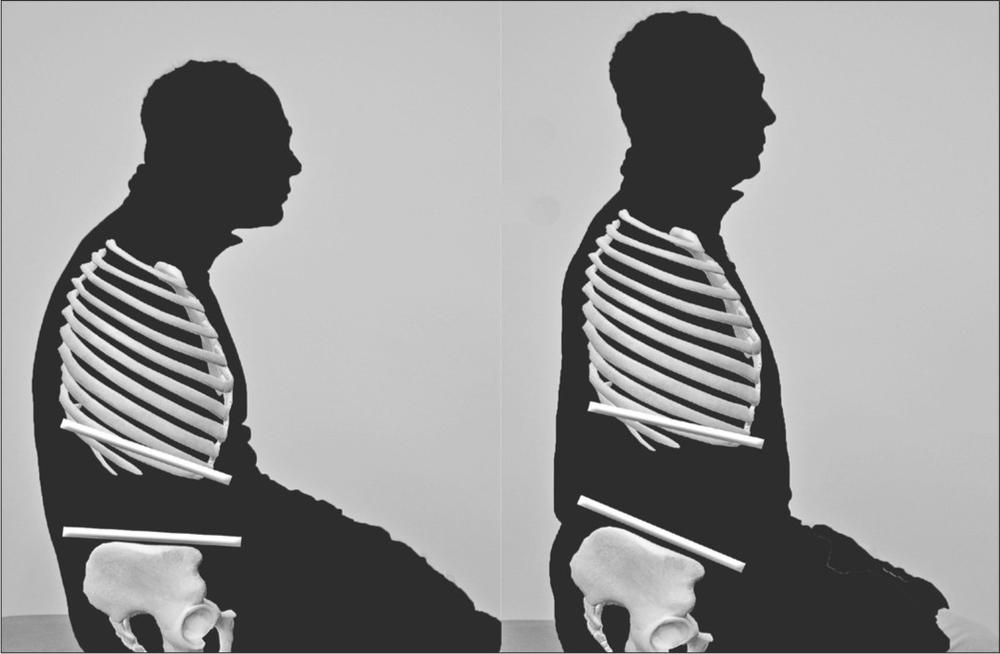

Slumping concertinas your ribs together

The loading of the head and shoulders pushes down on the rib cage, causing the intercostal muscles between the ribs to shorten (see Figure 3.5), and over time they can lose much of their natural elasticity. Eventually, under continued loading, they learn to play no part in normal respiration. In extreme cases, a patient’s chest will appear to be concave, with the sternum (the cartilage that runs down the front of the rib cage) drawn back towards the spine and downward towards the pelvis. It is little wonder that this person cannot get a satisfying inhalation.

Figure 3.5: Slumped and concertina-ed ribs versus upright, open rib cage

Even if you are very strong, and gravity is not the force that causes you to slump, there are other potential reasons why you might adopt this posture when you have COPD. Rather like a hedgehog, we humans have a natural reaction to curl up when we feel desperately endangered. Not being able to breathe is one of the most stressful things that we can endure. The feeling of suffocation you get when you have a COPD exacerbation is so great, is it little wonder that the resulting uncontrollable panic makes sufferers want to curl up in the foetal position to get some relief? Again, over time this can become an automatic reaction to the stress of breathlessness that immediately leads to the intercostal muscles contracting.

I want my patients to become aware that they are not moving their chest, and how if we can coax these muscles back into action, they can regain mobility, and once more play an active part in respiration.

Slumping pushes your diaphragm onto your belly

As the diaphragm acts like a muscular skirt across the bottom of the rib cage, the slumped upper body pushes down, fixing the diaphragm in place on top of the intestinal mass (see Figure 3.6). In some patients (especially those who have been on multiple steroid treatments) the intestinal mass has become quite bloated, making this situation even worse.

Figure 3.6: Slumped belly versus supportive and toned abdominals

With the ribcage depressed so that the whole weight of the upper body is pushing down onto the abdomen, the diaphragm is unable to work as it is designed to. Normally, in a balanced body, the diaphragm should be lifted off the intestines and tensioned by the open rib cage; this leaves a pressure gradient between the upper body and the lower body for the diaphragm to draw downwards with little resistance on inhalation. If you remember, a healthy individual gets approximately 75% of their resting tidal volume from the action of the diaphragm. Slumping forwards and preventing the diaphragm contracting is possibly the most profound effect of the kyphotic posture.

It is interesting to note that a good percentage of my COPD patients get acid reflux or have a diagnosis of hiatus hernia. To me it is little surprise that they get this reflux of stomach contents travelling up the oesophagus, as downward pressure on the stomach from a compressed diaphragm could potentially cause this to happen. Most of my patients have said that their symptoms of reflux have either reduced or disappeared after following the Brice Method. This is not something I can claim responsibility for, but it would be interesting to do some further research on this effect.

A further issue that can be linked to the diaphragm being pushed down onto the belly is an impaired lymphatic flow. The lymphatic system is rather like the body’s sewage system, and it is very reliant upon the action of the diaphragm to allow the system to work effectively. With the diaphragm caught between the overly pressurised lungs and heavily pressurised gut, it may contribute to the pooling of waste products around the body and the sluggishness of lymphatic flow. This can lead to a patient experiencing fatigue, malaise and even pain.

Posture really matters

I hope you have taken the time to understand this chapter about the benefits of healthy posture.

I try to give as persuasive an argument to my patients as I can to convince them that they must try to adopt an open chest posture because otherwise they will always struggle to reach their full breathing potential.

I strongly believe that you must first address postural issues before you try to improve your breathing technique and before you start the Brice Method exercise programme.