COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) is an umbrella term used to classify a number of conditions of the lungs that impair breathing. Bronchitis and emphysema are the two most frequent conditions under this umbrella term, but there is a whole range of complaints and illnesses that are labelled under the same banner. The meanings of the terms which make up the acronym are as follows:

| chronic: | it is a long-term condition and does not go away | ||

| obstructive: | your airways are narrowed, so it’s harder to breathe | ||

| pulmonary: | it affects your lungs | ||

| disease: | it is a medical condition. |

The UK’s Health and Social Care Information Centre questioned medical practices in England and reported in March 2015 that over 1,034,578 people were registered with their GPs as having a diagnosis of COPD, an increase of over 2% in a single year.

Many other people with breathing difficulties go undiagnosed and/or do not go to their GP for help or diagnosis. This means the issue may be even more common than these statistics indicate. This is borne out by The Health Survey for England 2010, which estimated that 6% of adults had probable airflow limitations consistent with COPD. If this 6% figure were true it would be equivalent to around 3 million people in the UK.

This book is the culmination of thousands of hours of work with a wide range of breathing and lung conditions under the banner of COPD. It includes a section that details the personal feedback from hundreds of patients suffering from COPD, and is designed to help readers understand how their breathing can be adversely affected by the way they behave, stand, sit and move, but conversely how they might be able to improve their breathing by doing these simple everyday activities differently.

The results from those who complete the programme are quite staggering. I have found that patients’ blood oxygen saturation increased during the first session with me from an average of 94.5% to an average of 97.6%. Blood oxygen saturation gives an immediate indication of how much oxygen is being absorbed into the bloodstream from the lungs, and is used extensively to monitor patients’ progress. I have also found that patients report on average a 64.5% improvement in their quality of breath within the first session. Hopefully, using the techniques in this book you will benefit as much as one of my average patients. You will get the opportunity to try this out for yourself if you do the first Landmark test at the end of this Introduction (page 13), and then re-do this test as recommended at various stages in the book.

The development of the Brice Method has, in part, been driven by the desire to find an alternative early stage intervention that might be able to delay the need for expensive pharmacological treatment of COPD. The development of the programme has been gradual. Many of the exercises are treatments that may have been used by previous generations of medical practitioners and, in some respects, it uses skills that may have been overlooked when ‘high tech’ alternatives were developed. As with most other lifestyle-related conditions, the use of physical activity for COPD is aimed at the causes of the condition, not the symptoms.

Built into this book is a series of simple exercises to help a person with COPD listen to their body, understand their dysfunctional breathing patterns and learn to manage and cope with their condition.

Whilst there can be no guarantee that the Brice Method will definitely help every person with COPD, the vast majority of patients have found this innovative programme useful to some degree or another. Most of the patients who have gone through it have said that the programme has dramatically improved their lives.

The method is designed to be simple to implement. It is based upon the idea that we should use our lungs the way nature intended. Despite the method being simple, patients who have done the programme have reported that there are profound changes that have helped them breathe better, move better and live better.

Who is the book written for?

This book is aimed specifically at the layperson with COPD, and as such you will not find numbered references or reading lists, as it would affect the flow of what is essentially a self-help book.

If you have COPD you will probably have been given an idea of how badly you are affected by your condition. All COPD patients are given a number from 1 to 5 as to how much of an impact their breathlessness has on their daily living. This is called the ‘MRC grading’. The five divisions are listed and explained in the box.

Medical Research Council Breathlessness Scale

| MRC1: | Not troubled by breathlessness except on strenuous exertion | |

| MRC2: | Short of breath when hurrying, or walking up a slight hill | |

| MRC3: | Walks more slowly than other people, stops after a mile or so, or stops after walking for 15 minutes at own pace | |

| MRC4: | Stops for breath after walking for about 100 yards, or after a few minutes on level ground | |

| MRC5: | Too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when undressing. |

As the Brice Method is a very low-key programme of advice and exercise, it is suited to all five levels of MRC grading. The programme aims to assist those with mild breathlessness to learn what they can do themselves to help prevent their breathlessness worsening due to poor lifestyle choices. Conventional pulmonary rehabilitation has previously been deemed unsuitable for those COPD patients with an MRC5 grading. This is due to the nature of the physical exercises in that programme being too intensive for people who are severely affected by their breathlessness. Unlike conventional programmes, the Brice Method has been shown to work effectively with MRC5 patients. This is partly due to its graded, step-by-step approach, focusing on low-level tasks before it moves on gradually to more active stages. The very breathless patients can start off with hardly any exertion at all, only progressing when they have mastered the stage they are working on. If they find that they are unable to progress beyond a certain stage due to other health conditions, then they will still have benefited up to that point.

Why the book was written

I feel that the Brice Method has come about as I have a different perspective on breathing from many of my counterparts. I believe that my background as a competitive athlete helped me to develop a critical eye on how the body can limit a person’s ability to breathe, and ultimately limit their physical performance.

During my athletic career, I was always aware that I had a habit of sizing up my opponents before a competition. Being a multi-event athlete, I regularly competed against shot putters, long jumpers, sprinters, hurdlers, pole-vaulters, javelin throwers and long-distance runners. By sizing them up, I don’t just mean the opponent’s height and weight or bulk; I mean that I looked at their posture and their movement patterns. Nearly every athletic event has a breathing pattern that goes with it. The oomph you need for a shot putt contrasts with the rhythm of the hurdles, and the strong control needed for the pole vault contrasted with the relaxed requirement of longer distance running events.

As an athlete I was lucky enough to be on the first wave of guinea pigs in the UK who routinely had their physiological capacities tested. These tests included measurements of the power output and strength of our muscles, our flexibility, as well as a plethora of other tests. One of the tests was the lung function test, which is the same test dreaded by most COPD patients. Being competitive, I quickly learned how to try to beat the tests to maximise my score. It was natural for me to try and open my lungs up as fully as possible to get the best score, something that has influenced my working with my patients.

When I started working with people with COPD I immediately wanted to use my experience and knowledge to help them be more active, especially when so many of them looked like they had forgotten how their lungs worked. It is probably not surprising that the techniques I used to get the extra 10% out of my lungs as an athlete would provide an even greater benefit for people with lung and breathing problems.

Pharmacological treatment of COPD

Over the last two decades, the advances in medical knowledge and respiratory medicine have been extraordinary. The research and understanding of the scientific minutiae of the potential causes and intricate treatment of specific issues of impaired breathing have undoubtedly helped many millions of people.

Whilst it is wonderful that we have these powerful tools, many practitioners are now starting to ask if we are using these drugs too readily. In the UK, and in other advanced countries, we are starting to see drug resistance. It may be that we have become a little too quick to use these highly advanced treatments to manage symptoms of breathlessness, especially at the early stages of diseases such as COPD, where patients should possibly have the chance to address the lifestyle issues that may have caused the symptoms in the first place.

When I treat people who have had COPD for many years, and are showing the obvious effects of long-term steroid and antibiotic use, and I show them the simple exercises that start the Brice Method journey, some of the more knowledgeable even ask me, ‘Why haven’t I been shown this before?’ In my clinic I have had up to 98% of my COPD patients say they have felt significant benefit to their breathing from a more holistic approach to their initial treatment using the Brice Method. It may be that the cost of doing clinical trials to demonstrate the effectiveness of interventions is prohibitive for simple interventions like this. In the ‘real world’, it is usually only pharmaceuticals that can reap the financial return to justify such monetary investment.

Holistic approach

The Brice Method aims to look holistically at the individual patient, and what might be contributing to their breathlessness, bearing in mind other conditions, not just the lungs.

Many COPD patients have specific illnesses, or conditions, directly linked to their breathlessness. Others have medical issues that would appear at first glance to have little or no association with their breathing problems. How could a patient with arthritis and two knee replacements have those two issues associated with their breathlessness? Or, how could a patient with chronic back pain that has debilitated them for a decade have been predisposed to present at a COPD clinic? The answer is quite simple, but often overlooked.

In reality, many of the patients that present at clinic have either one significant, or a number of, health or lifestyle issues that may in some way have led them to be more inactive. Some of these issues are physical, like a leg or back problem; others can be psychological. A large number of the elderly patients are clearly resigned to having poor health because they have been told by well-meaning people that ‘there is nothing more than can be done, it is the effect of aging’.

True breathlessness often creeps up on you

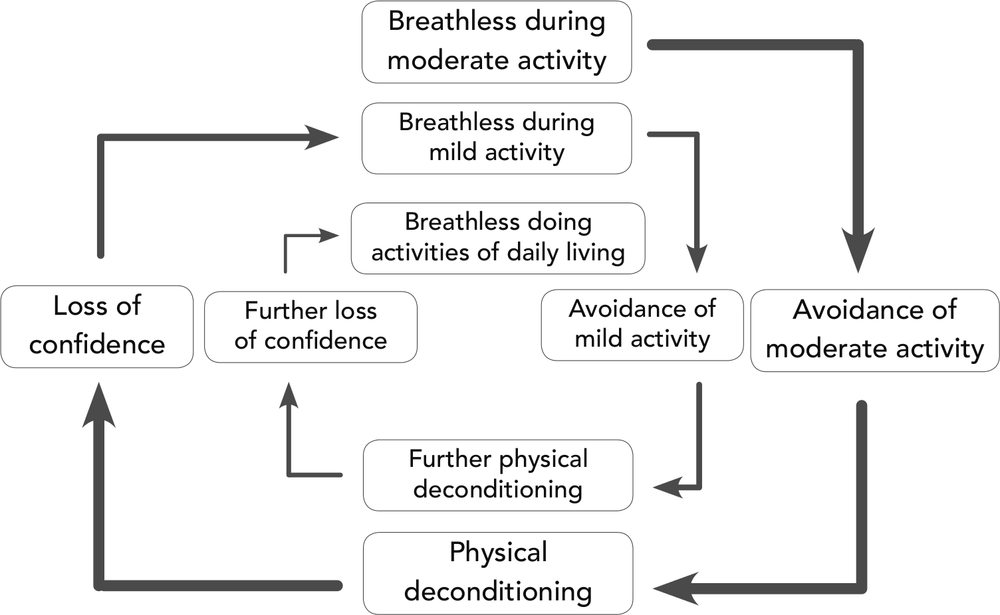

To explain how easy it is for breathing problems to creep up on you, health professionals use a diagram called the ‘spiral of de-conditioning’ (see Figure 1) to demonstrate the typical onset of breathing problems in patients with COPD. The ‘spiral’ is commonly used in pulmonary rehabilitation programmes to explain how a patient can become less and less able over time due to relative inactivity.

Figure 1: The spiral of deconditioning/breathlessness

This spiral of ever-reducing ability can take a considerable period of time to manifest itself. Its gradual creeping effect means that some people will only realise that they have been getting worse when they really can’t do something simple like stand up from a chair. Other people will find this process can be extremely rapid. For example, a long stay in hospital or a severe chest infection can mean you go from being able to do relatively moderate activities to not going out at all within a week or two.

Deconditioning like this over time is effectively a Catch-22 situation. The negative spiral continues until, eventually, even the slightest physical movement becomes challenging, and it is at this stage patients will present at one of my COPD clinics, saying that they find any exercise makes them feel stressed or panicky.

The good news is, for most people, the cycle is reversible to some degree or other. Whilst I can never promise that people will regain their confidence and physical capacities in full, with consistent and gradually progressing activities, nearly all COPD patients I work with feel they have managed to regain some control of what was a downward slide to complete loss of independence.

How to use this book

This book has been structured in four stages, which mimic the way in which I would teach a client in my clinic.

- First, I explain in detail about where the lungs are and how they should work. This means you may get an insight into why you will be doing the later exercises.

- Secondly, I cover some of the main breathing issues people with COPD tend to demonstrate.

- Thirdly, I explain why you should adapt your posture to breathe better before I even start to give you any physical exercises.

The exercise component of the Brice Method (stage 4) only begins at Chapter 5. It starts with upper body exercises, moves on to lower body exercises, then covers breathing on the move and finally how to develop more oomph.

The book then covers further information about living with breathlessness.

You will be expected to do regular daily homework exercises to help you undo some of the bad habits that you will undoubtedly have developed over the years. To help you locate these exercises easily, they are shaded dark grey on the outer edge of the page, with the name of the relevant exercise written on them.

Your attention will be drawn to three key ‘landmarks’ throughout the book where you can assess the quality of your breathing before and during the programme. These landmarks mirror the measures that I use with my clinical patients. I have found that using these ‘self-test’ measures has given focus, confidence and adherence to up to 95% of these patients.

The first of the three landmarks is undertaken before you even start Chapter 1, and provides you with the reference point to measure your full progress against. I have provided the results of 302 COPD patients in Addendum 1 (page 135), so that you can compare your results with those of my clinical patients.

There are some exercises that will benefit from some equipment. I have explained in Addendum 2 (page 141) how you can start off without investing any real money, and what options you have if you need to buy some more suitable equipment once you have full confidence in the programme.

If you have other medical conditions that are equally limiting to you as your breathlessness, or even more so, you should re-read the initial warning advice right at the start of the book and consult your GP before starting the programme, as well as following the advice on monitoring pain and discomfort that comes next in this Introduction.

Monitoring any pain

If you have recently been advised by your doctor to exercise, or you are starting out on this programme from scratch, the likelihood is that you will have done very little, or no real, physical activity for some time. As I have said, chronic conditions like COPD creep up on you slowly and you may not realise how rusty and ‘graunchy’ your once healthy, active body has become until you start to move it outside of your usual limited range of motion.

Discomfort or pain

Jane Fonda, one of the first high-profile fitness leaders in the 1970s, had a mantra of ‘no pain, no gain’. Some people still have this mantra in mind when they think about exercising, and the prospect of having to exercise hard could be one of the reasons that they have avoided exercise at all costs. Fortunately, our understanding of exercise, or better still physical activity, has moved on immensely in the last 40 years and I would hazard a guess that even Fonda herself might advise against her formerly gung-ho approach after having had two hip replacements. If you had any worries that the Brice Method was going to ask you to work hard, rest assured, this is not the case.

However, to say that you can go through the entire programme feeling absolutely no discomfort or pain would be a lie. One of the aims is to help you develop and adapt to a new, more active lifestyle, but the main objective of the Brice Method is to teach you to move without feeling out of control, especially not becoming uncomfortably breathless.

Pain is something that should be considered useful when it comes to physical activity. Our nervous system is designed to quickly tell us when things are not right, and, at its simplest, has helped humankind to develop to where we are today by avoiding threats to our survival. When it comes to exercise, pain is a great measure of what should be done and what should not be done.

Most of my patients have been relatively sedentary for some time, not moving their limbs or their bodies very much. Usually they have been so inactive that some of the simple movements in the first set of exercises designed to mobilise the upper body may initiate pain in the chest, neck or shoulders.

You will need to realise that pain is relative. Some people have higher pain thresholds than others. It has been found that people with breathing disorders who have low levels of oxygen in their bloodstream are more susceptible to chronic pain, but can also have a heightened sensitivity to pain. The good news is that many of the hyper-sensitive patients I work with find that their pain awareness reduces with gentle, sensible physical activity.

Pain guidance

Rather than simply giving up or totally avoiding the exercises, I have some guidance as follows.

- Try a movement and if ‘pain’ arises, stop the movement and return to the starting position of the exercise.

- If the pain is dull and achy, and if it dissipates and goes away quickly, then this feeling is not pain but is really discomfort.

- Check your body alignment against the exercise advice given and repeat; usually this will make things feel easier. If not, don’t worry, time and repetition will help.

- By repeating the movement, the joints, ligaments, tendons, fascia and muscles all warm up and start to mobilise, and the range of motion generally increases.

The above sensations are either ‘discomfort’ or ‘good pain’, and once your body has overcome the shock that you are asking it to move, you will soon be reassured that it is acceptable, even normal, to feel something like this.

Caution

- If a movement causes a severe, sharp, stabbing pain then this is not such a good sign, and is an indication of ‘bad pain’.

- If the pain does not subside within 30 seconds, then that is also a sign that it is ‘bad pain’ that should be avoided until you are sure you aren’t doing something incorrectly.

If you do get sharp, severe pain with a movement, even if the pain is very severe, it does not necessarily mean that you are a lost cause, and you should give up. Before you discount an exercise, you must ensure that you are not holding your body in an incorrect posture before you start. For example, it is common for someone who has not used their arms for a while to be hunched over, and their shoulders to be stuck in a rut. By squeezing your shoulder blades backwards and together behind your back, you can usually enable your arms to move more freely and naturally.

Warning

If you have tried the above and want further guidance, you should either seek further advice from a qualified fitness specialist or see your doctor. You will have to be the judge as to when you may need external help, as only you can know how your body feels.

In the end, it will be up to you to create your own pain monitoring language. Gradually you can then use this to measure how much pain or discomfort is right for you, as well as checking that it is getting easier and less painful and not the other way around. This pain language will be your long-term guide as to how hard and for how long you can happily be physically active in the future.

Not everyone will be capable of progressing through the full programme. Some of you may have very severe bodily or health restrictions, and you will have to decide when you should stop. You need only progress to where your body realistically allows.

Keeping track of your progress

There are two ways that you can monitor and track your progress through the Brice Method.

Landmark self-tests

The first measure is the Landmark self-tests that I have mentioned before and that you should do at three specific times throughout the book. The idea here is that you will be able to assess your awareness of your breath, and how you feel you are breathing at these three key stages. The first landmark test follows this Introduction. It will then be repeated after Chapter 4 (page 56) and after Chapter 7 (page 91).

Daily exercise record sheet

The second measure of your progress will help you track the daily homework exercises that you will be given along the way. You can decide which exercises you wish to do at each stage, and wish to carry on with throughout the programme, and you can use the daily exercise record sheet on page 12, to track each week’s activities. This is a very simple tracking sheet to use for your practice on the exercise stages of the programme, where you have to practise regularly to develop a new healthy habit.

You will find record sheets covering a five-week period in Addendum 2 (page 145) for ease of photocopying, or you can download a copy of the record sheets from my website, www.paulbrice.net.

Now it is time to do your first Landmark self-test.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | |

| Early morning |

|||||||

| Mid morning |

|||||||

| Afternoon |

|||||||

| Evening |

Table 1: Practice record sheet – mark an ‘X’ in the relevant box for each time you do one group of the exercise routines.