♦ Visualisation exercise – spongy lungs

♦ Exhalation – the driving force of breathing for the COPD lungs

♦ Pursed-lip breathing

♦ Pacing and timing

Parachute counting

Paced breathing

♦ Inhalation muscle training

♦ Pros and cons of nasal breathing

♦ Abdominal breathing

♦ Are you ready to progress?

On average I see more than 200 new patients a year, either walking in or being wheeled in, totally oblivious to the fact that they can have some control over the way that they breathe. The majority of these patients come into my clinic working desperately hard to suck in air against a compressed chest and lungs. Whilst I am quickly able to show them that posture has a big part to play in the amount and ease with which air can be inhaled, I find many have been taught techniques that are not always specifically designed for COPD patients.

When I started working with large numbers of COPD patients I suddenly realised that most of the breathing techniques they had been recommended differed very little from standard breathing techniques used for the general population with healthy lungs, or for asthma sufferers.

If you take time to look on the Internet, in COPD advice booklets, there are usually four breathing techniques that are recommended as a standard. They are:

- pursed-lip breathing

- inhalation muscle training

- nasal breathing

- abdominal breathing.

Of these four techniques, only one actually focuses on exhalation (pursed lip breathing); the other three highlight inhalation exercises.

From our de-slumping exercise, you should hopefully recognise that the lungs can be opened up pretty easily, and this is why I tend to shy away from the inhalation training techniques, especially at the start of the programme when I am trying to instil relaxed, quiet and comfortable breathing techniques. I find the inhalation training techniques tend to aggravate the situation, as the emphasis is on breathing in hard, and controlling breathing in a forceful way, all of which tend to make my patients more, not less, stressed!

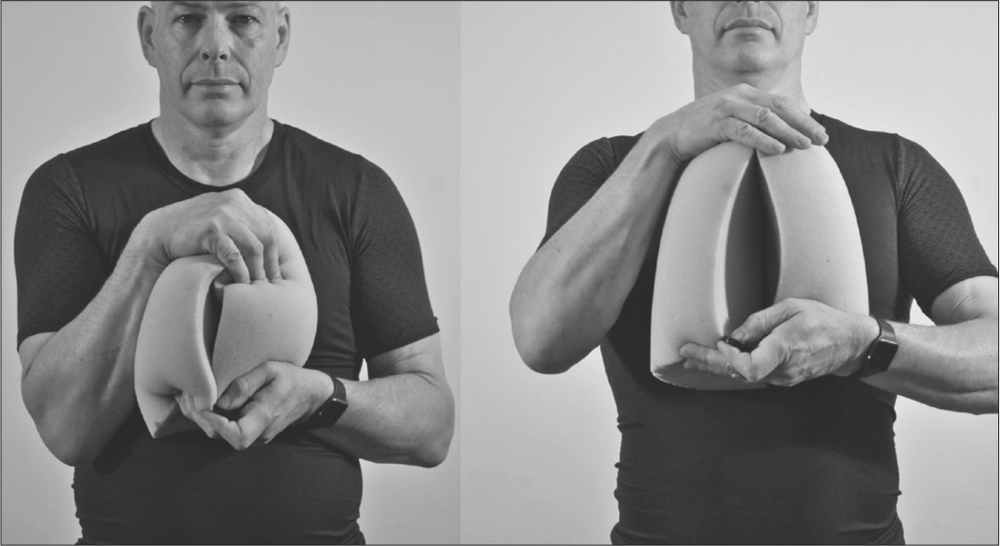

To get this message across to my patients clearly, I use a simple visual exercise to show how the lungs work when you are breathing. The exercise usually sticks in the mind once you have seen it because it is so obvious. Whilst it could be seen as a vast over-simplification of the process of breathing, it is more pertinent to most patients with COPD than you would at first think.

Visualisation exercise – spongy lungs

I use a big sponge that is about the same size as my lungs – see Figure 5.1. When you breathe in, your shoulders are drawn back and down, which opens your rib cage and lifts it off your belly. Inside your chest your lungs are like sponges that are also open, with plenty of air in them. It takes relatively little effort to get the air in, as the spongy lung is expanded automatically.

Then I squeeze the sponge and breathe out slowly, showing them that the air should flow out easily and without too much effort. As I expand my chest and draw my shoulders back again, I release the sponge and it pings open, just like the lungs will do if the chest is kept open.

Figure 5.1: Spongy lung demonstration

I ask patients to imagine they are breathing along with me as I repeat the exercise. I get them to think that they are breathing out slowly as I constrict the sponge, blowing through pursed lips to slow down and regulate the flow of air.

I repeat this a few times, asking patients to follow my lead and making sure they don’t suck in too hard. If they do breathe as they habitually would and suck in lots of air, I warn them that they will almost certainly feel ‘light headed’, as the body is quickly over-oxygenated. As mentioned in previous chapters, the body wants the chemistry of the blood to be in balance: too much oxygen is just as bad as too little.

I explain how these deeper breaths are drawing air right into the air sacs, rather than simply flowing up and down the larger pipes of the lungs.

With practice, patients tell me they find this new breathing technique very relaxing. The lungs rebound open and the in-breath just seems to happen naturally. Because the rib cage is lifted off the abdominal mass, the diaphragm can work unhindered without having to try and force the belly out of the way as it descends. The intercostal muscles between the ribs are free to do their thing, lifting and separating if a deeper breath is needed. With time, the neck muscles no longer have to be used, unless extreme exertion is taking place, just like people with healthy lungs.

Quite simply, this technique teaches very natural breathing. It is relatively stress free. And even when the lungs are really badly affected by COPD, it can provide some degree of relief for the patient, something my patients are usually very appreciative of.

Exhalation – the driving force of breathing for the COPD lungs

Over the years of working with COPD patients I have found that, whilst I had been taught to place an emphasis on training people to actively breathe air into their lungs, it appeared to cause them considerable stress. Most patients had already learned to suck the air in hard, or had been taught previously to do so. I found that active inhalation training did not seem to relax patients very much. In fact, it seemed to have the exact opposite effect, making them appear very stressed, tight and anxious.

I learned to adjust my emphasis from active inhalation to active exhalation from an open chest. This seemed to work so I focused on two existing breathing techniques: pursed-lip breathing and paced breathing. I use the pursed-lip breathing technique as it has been used in yoga for centuries and modern physiotherapy worldwide. I also practised a range of paced breathing techniques similar to those that are used to promote healthy breathing and found a pace that seemed to work very effectively for patients with COPD.

Pursed-lip breathing

Breathing out through pursed lips can act to help regulate the speed and extent of exhalation. Think of letting air escape from your mouth as if you are trying to flicker the flame of a candle in front of you rather than huff and blow the candle out. This technique is used in many exercise routines, from yoga to weight-lifting to Pilates and in COPD rehab programmes, and is the only one of the four traditional COPD breathing techniques that I find useful with almost every patient. It is especially useful during the more advanced parts of the Brice Method, when patients are progressing to becoming more physically active.

A slow and controlled exhalation allows time for the oxygen in the deep alveoli to diffuse across into the bloodstream. If you blow out too hard or too quickly, the air that is in your lungs gets expelled before the oxygen has had time to move across to the blood.

Pursed-lip breathing also acts to prime the lungs effectively. I want you to picture in your mind a plastic bag that is held open with lots of air inside. If you keep the mouth of the bag wide open and push the sides of this bag inwards, all the air will rush out in a quick huff. The airflow is unrestricted and the bag collapses pretty much completely, all at once. When I watch my patients breathe out through a fully open mouth, this is how deflated their lungs and their chest look to me.

In contrast, once again picture the fully open bag of air. This time I want you to think about closing up the mouth of the plastic bag so there is only a small gap for air to pass out. Pushing the sides of the bag will cause a build-up of pressure, with a controlled flow of air going out. Picture the bag expanding out as the air is pushed out steadily. Think how a similar airflow out of the mouth would help increase the pressure in the exhaling lungs.

A good (but somewhat extreme) example of how this pursed-lip breathing can help with physical activity is looking at how Olympic weight-lifters expel the air with a hiss when they are lifting a heavy weight. Imagine how weak the lifter would be if he/she allowed air to escape too quickly through a fully open mouth. He/she would have all the strength of a floppy lettuce leaf, and there would be a lot of deflated weight-lifters lying prostrate on the floor!

At rest, exhaling slowly and gently can mimic the feeling of sighing. When we sigh, it has a very relaxing and calming effect on the body. Contrast this to when a patient is struggling to get enough air in, and the feeling of panic that this creates, and you can see why focusing on the exhalation is so important.

When the lungs have been emptied, the body automatically draws air in, partly by the natural action of the diaphragm drawing down into the space above the gut and partly due to the recoil of the elastic membranes of the bronchioles and alveolar ducts.

Adding pressure to the exhaled air has another beneficial effect for the body. If the exhaled air is at a relatively low pressure in the lungs, the pressure of gases is rather like what you might find at high altitude. Mountaineers take oxygen with them as they climb to combat the rarefied air. The air pressure is lower than that at sea level and oxygen is absorbed much less efficiently into the bloodstream. Exhaling through pursed lips increases the air pressure considerably, rather like the air pressure at sea level where oxygen is taken up more readily by the bloodstream.

Pacing and timing

The pace at which you breathe is the second key aspect of exhaled breath control that is generally most effective when used alongside the pursed-lip breathing you have just been told about. Paced breathing for COPD patients tends to be taught in a ratio of 2:4, that is, you should breathe in for a count of 2 and out for a count of 4. The idea is that you learn to slow your breathing rate down and allow a longer period of time for the oxygen to diffuse into your bloodstream from the alveoli over a count of 4.

This 2:4 breathing technique is used extensively for meditation, but when a COPD patient starts to be active, they have tended to find the 6 counts to be too long for their reduced capacity to manage. I worked alongside my patients to find the pacing that seemed to be most effective and it surprisingly matched the rhythm that front crawl swimmers use. This pacing time of ‘3:1’ for the ‘out:in’ breath cycle was the one that patients appeared to find the most natural for them. Over time I have found this timing works especially well for walking or rhythmic cardiovascular type exercises, and is thus a great one to practise and adopt early on in training programmes.

As some patients count faster than others, especially if they are stressed out, I teach them all to do what I call ‘parachute counting’. When a free-fall parachutist jumps out of a plane, instead of counting ‘one’, ‘two’ and so on, they count ‘one thousand’, ‘two thousand’ before pulling the cord to release the parachute. Adding the word ‘thousand’ to their count helps them to retain the single second spacing between the numbers counted. In doing so, they get enough space between them and the next person jumping out of the plane so that they do not get someone landing on top of their parachute.

Parachute counting

Before you try this breathing exercise, read it thoroughly and understand what you have to do. Only once you feel you understand what you need to do should you try the actual exercise that follows. This exercise should help expand your lungs automatically, drawing air into your lungs naturally.

To fully understand this breathing technique, you are required to count to yourself in ‘parachute numbers’. As explained above, this means that each time you say ‘one thousand’, approximately one second will pass.

- Without first breathing in, gently exhale, through pursed lips, saying slowly to yourself: ‘one thousand, two thousand, three thousand’.

- Inhale passively whilst slowly saying to yourself: ‘one thousand’. (You will be surprised that your lungs draw air in without you having to work, as long as you don’t slump!)

- Continue to breathe in this simple cycle. If you get the timing correct, each breath cycle will take you approximately 4 seconds and your breathing rate will be limited to 15 per minute, generally slower than would normally be the case for people suffering from COPD.

It is important that you do not suck air in deeply at the start of this exercise. You should have enough in your lungs to exhale for a ‘three thousand’ count. Inhaling at the start is likely to make you focus on inhalation rather than exhalation. Also, do not try to fully empty your lungs as this will add tension to the stretch receptors in your lungs and make you suck in hard for the next breath.

Sometimes patients find that if they do this exercise at complete rest they do not need much oxygen at all. You may find it takes a little longer than the ‘one thousand’ count for the lungs to draw air in again. My advice is not to push or rush the in-breath, at least until you start adding some of the more active exercises to the technique. The prime concern is to avoid sucking the air in actively as this will simply add stress to the situation.

Paced breathing

- Sit tall and comfortably.

- Without first breathing in, gently exhale, through pursed lips, counting: ‘one thousand, two thousand, three thousand’.

- Inhale passively for a count of ‘one thousand’.

- Repeat this cycle.

Advice

If you are finding it difficult to exhale slowly for the count of ‘three thousand’, then you are most likely forcing the air out too fast. It is easy to try and blow very hard so that almost all the air is expelled in the first ‘one thousand’. By doing this you are stressing your respiratory system as you will have no air left in your lungs to take you to the full ‘three thousand’ count. It also means that you will have the air in your lungs for less time. This will limit the ability of your blood to take up the oxygen from the alveoli. It will also mean that you are highly likely to go into the ‘15% stress zones’ that I explained in Chapter 2 (pages 33-4).

Inhalation muscle training

Inhalation muscle training may not be ideal for the COPD lung. In Chapter 2 of this book I mentioned the conventional advice on breathing techniques and highlighted the fact that the abdominal breath training focused on inhalation. I briefly covered the fact that focusing on inhalation may lead a person with COPD to have to work harder than they should need to in order to breathe. The three main reasons why I prefer not to emphasise inhalation muscle training for early stage COPD patients are as follows.

- If your rib cage is already expanded by good posture, you are unlikely to need to strengthen your inhalation muscles to any real degree. That is, at least until you are exercising really hard. It is unlikely that many COPD patients will be able to, or expect to, work hard enough to have to train very strong inhalation muscles. If the body is positioned correctly, the diaphragm does not have to exert effort to push the belly down, plus the ribs do not have to be forced up against the tight chest muscles. In addition, the shoulder blades do not have to lift the weight of the head, as it is already balanced in its rightful place.

- Inhalation can, and should, be a relatively passive and stress-free action. I believe it is wrong to teach patients to breathe in very hard as it is much more likely to be stress inducing and will do little for reducing anxiety or breathlessness. Inhaling too strongly increases the likelihood of the lung overexpanding into the 15% stress zone.

- I believe that active inhalation training is not good for COPD patients because it promotes the same modified breathing pattern that smokers use when they take a drag on a cigarette. Over many years of practice, smokers learn a different way of breathing than the rest of us. They suck on their cigarette using mainly their neck muscles. This acts to engage the accessory muscles at the front of the neck, inducing the tight upper crossed breathing that many COPD patients demonstrate, and may even be due to the new movement patterns learnt when drawing in smoke. I teach these patients how to breathe in a relaxed, not a tense, fashion. All you need to do is imitate the drawing in of smoke from a cigarette and you feel that the air is being sucked into the back of your throat, by neck muscles. If you are a non-smoker, think about sucking on a straw. Have you ever had a very thick milkshake and got tired neck and face muscles when it was too thick to suck? That can be the extreme feeling you get if you have COPD and are struggling to get air into your lungs.

Nasal breathing

Many of the new patients that I speak to have been told always to breathe in through their nose. They sit with their mouths clamped shut, sometimes sniffing air noisily in through their nostrils, even if they have nasal congestion, an exacerbation of breathlessness, or even when they are trying to be physically active.

There are pros and cons to teaching nasal breathing to COPD patients. When I was taught how to show COPD patients to breathe there was great emphasis on the benefits of nasal breathing. I worked with this technique, prompted by the evidence of research demonstrating everything from the fact that the hair in the nose filters the air, the folds in the soft palate warm the air up, and the cells in the nasal cavity release minute amounts of nitric oxide to act as an antiseptic to the cell linings of the lungs.

Most breathing programmes nowadays emphasise the benefits of nasal breathing and seem by default to have been used as the go-to technique for COPD patients. There are even those who advocate nasal breathing to extreme levels, recommending that you should nose-breathe when you run. The idea here is it will help you run faster.

I have found that whilst this breathing pattern is very useful for people with healthy lungs, patients with COPD seem to benefit more from having a more open airway, without the restriction of having to breathe through small nasal passages. This is especially the case when they have started to become active and their requirement for unrestricted air into their lungs seems more important than its warmth or the presence of minute molecules of nitric oxide, etc.

I have good reason to decry the overuse of nasal-only training, this time, from my experience as an athlete. If I ever saw an athlete racing an endurance race on the track and they were breathing solely through their nose with their mouth clamped shut, I would either show you someone who would be in great pain within three minutes, or alternatively, someone who was destined to come last. The simple fact of the matter is that when the body has an oxygen demand greater than it is currently receiving, you need to get the air in quickly, effectively, and in as stress-free a way as possible. This is exactly how I train my patients to breathe. That is, at least until they can use their lungs in a more normal, healthy pattern without stress. The reality of the situation is that a COPD patient is challenging their lungs to almost the same extent as a runner, so it makes sense to me to get as much air into the lungs as the body needs.

Another reason I try to avoid nasal-only breathing techniques for COPD patients is that recent research has demonstrated how strong nasal breathing recruits the accessory muscles of the neck. These are the weak and inefficient muscles that merely act to lift the top two ribs. Finally, I strongly feel that COPD patients should start by avoiding nasal-only inhalation, especially when they are being physically active, because it acts by restricting the refill rate of the lungs, creating a relative pressure vacuum that forces the patient to rely entirely on muscular effort to inhale. Sniffing air in hard can thus induce stress and agitation, exactly what I try to tell my patients to avoid at all costs.

Exercise to demonstrate nasal breathing issues for COPD patients

Compare these two simple exercises.

Closed-mouth inhalation

- Put one hand around the front of your neck, gently touching your skin.

- Empty your lungs as fully as you can, and then …

- with your mouth closed shut, suck air into your lungs as quickly and as deeply as you can.

Not only will you notice that it takes several seconds to fully expand your lungs, you will probably feel how strongly it makes the sinewy neck muscles tighten up as they activate; you are also likely to find it quite noisy in your head, and I doubt that you will find it truly comfortable, as it is quite hard to suck enough air in.

Open-mouth inhalation

- Put one hand around the front of your neck, gently touching your skin.

- Empty your lungs as fully as you can, and then …

- breathe in equally through your mouth and the nose.

You will immediately see what I mean. There is less tension stress in the neck and the air travels in much more easily, without as much need to rely on the work of the neck muscles.

I fail to see why we would promote ‘nasal-only’ breathing as a good breathing technique for COPD patients who are just starting to learn how to overcome their dysfunctional breathing patterns. Personally, I recommend this technique only for those patients who get close to full use of their lungs. Healthy individuals can really benefit from nasal-only breathing, and this is well documented.

I maintain that, if the rib cage is expanded and lifted and the lungs are open, inhalation should be a relatively passive, natural and stress-free action.

Abdominal breathing

The last of the four breathing techniques that are currently used to help COPD patients overcome breathlessness is abdominal breathing. Personally, I feel that abdominal breathing comes about as an automatic result of good posture, rather than being an exercise to be learned in its own right.

This technique has already been discussed in Chapter 2 (see Figure 2.1). Pilates and yoga have similar techniques where you focus on expanding your ribs outwards. These aim to train you to actively engage and strengthen your diaphragm.

It is not that I disagree with the fact that working the diaphragm is important, it is simply that I find that COPD patients are better focusing on posture first, and the diaphragm will automatically engage as a result of having space to work in.

Unfortunately, whilst patients should always be told to first sit tall, this is not always the case. In my experience, rarely is there any real emphasis placed upon proper posture before undertaking breathing training. Failure to recognise the importance of posture means that many patients move straight to the breathing exercises and are more likely be under greater pressure than they would otherwise have to be.

Are you ready to progress?

Learning how to breathe in, without having to actively suck the air in, is a skill that will help you to master the art of relaxed natural breathing. This, combined with an upright controlled posture, can reduce the stress and tension in the body, and even mitigate feelings of anxiety that come with breathlessness.

Once you feel that you have can sit up tall and control your breathing so that you are not gasping or activley sucking the air in, you should think about moving on to Chapter 6 of the Brice Method. If, however, you still feel that you are very breathless and sucking the air in, do not worry. It may be that you need to practise the postural adjustments further and allow your body adequate time to change. Your current posture is likely to have taken years, if not decades, to form, and it won’t always be able to change immediately.