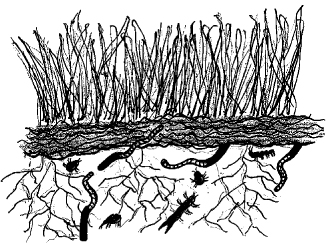

Living soil is teeming with life.

PLANNING A GARDEN |

3 |

OUR AIM SHOULD BE TO DESIGN AND BUILD an edible, productive landscape that is developed with long-term sustainability in mind. So what would be the indicators for a sustainable landscape? The three obvious indicators are soil health, water quality and types of plants, and we need to keep these in mind when we start the design process.

Whether you are building a herb and vegetable garden or developing the whole property, the process you want to implement should be based on sound ecological principles.

The components of an ecological garden can be remembered by using the acronym PAMS WASH.

Plants are producers. They make food, products (oil, fiber, clothing, rubber, and an endless list of things we use every day) and oxygen (which every living thing requires).

Our observations and knowledge about plant species will determine the types, varieties and numbers of particular plants we want to use. The types of weeds present on a site can also provide helpful information.

Weeds can be used as soil indicators (to some extent) and they are nature’s way of repairing damaged land. These pioneers restore the fertility of disturbed soil, so weeds should be seen as opportunistic plants rather than invasive plants.

We can keep weeding a garden every year (or after every heavy rain event) or we can plant our own pioneers to protect and build soil.

Pioneers are those plants that colonize and grow first in an area, and their role is to protect, change and build soil. Many fast-growing, nitrogen-fixing plants are pioneers.

We should implement strategies that will bring about both long-term improvement and yield to a landscape. It is important that we strive to restore damaged landscapes and make them productive — creating useful yields of food, materials and products.

Animals are consumers. While they eat plants and each other, they are important in every nutrient cycle. They provide the manures to feed soil life and make plants grow, they aerate and mix the soil, they provide the carbon dioxide that plants require for photosynthesis, and many are keystone species that determine the fate of an ecosystem.

» DID YOU KNOW?

A keystone species is one that plays a crucial role in the survival of the rest of the ecosystem. For example, sea otters protect large kelp fields from being eaten by sea urchins. Unchecked numbers of sea urchins would devour the kelp, so otters keep the urchin numbers low.

In forest ecosystems, large food plants (fruit and nut trees) may be keystone species as they provide food for large numbers of animals at particular times of the year when some food reserves are scarce.

Microscopic plant, animal, fungi or other single-celled organisms live everywhere. The soil is the most biologically diverse habitat on Earth, with about 50 billion microbes in every tablespoonful.

Living soil is teeming with life.

Healthy soil is teeming with life. If you weighed all of the earthworms, invertebrates, nematodes, bacteria, fungi and the literally millions of other organisms you would find about 2 lb in every square foot of soil.

If we assume that most of the soil life is confined to the top 8 inch then those 2 lb are found in every 60 lb of soil.

Without soil, there is no life on Earth, and this is why it is crucial that we really tend to our soils and look after them. The next chapter is devoted to creating healthy soil.

When planning a garden one of the first things to think about is: how am I going to provide enough water to keep the plants and animals alive, and then allow them to thrive? We might need to undertake a water audit to ensure that lack of water will not limit our aspirations of a productive garden.

Sometimes we can’t just rely on rain, and many fruit and nut trees may need twice the annual rainfall to produce. How we can harvest, recycle and better use water is discussed in chapter 10.

Humans tend to have a disregard for keeping our air, water and soil clean. Clean air, clean water and clean soil are fundamental rights for everyone (and everything else too), but we seem to keep polluting these anyway.

Allowing wind to pass through our gardens can prevent many diseases, such as mildew and other molds, by maintaining good air circulation.

Every garden needs structures, and these typically include gazebos (patios, entertainment areas), compost bins, trellises, retaining walls, seats and garden ornaments such as sculptures and bird baths. Structures are used to support plants, protect plants, provide a habitat for animals and allow humans to sit, rest and enjoy the garden.

These creatures are an integral part of every ecosystem, and have the ability to change environments for the better or for the worse. We have a moral and ethical responsibility to care for the planet, and creating functional garden environments is one small step each of us can take.

So, if humans are to work in the garden they need comfort (paths), shaded walkways and a tool shed nearby, even a small potting area. Working in the garden needs to be a pleasure, so they look forward to going out in the garden for both leisure and enjoyment.

We need to keep all the humans that live there in the best health and well-being, so we need to plan for nutritional and medicinal plants, and have areas of tranquillity with appropriate seating for contemplation or meditation.

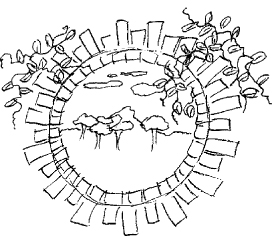

An ecosystem is a collection of interacting organisms and their surroundings. A forest ecosystem, for example, would include all the plants and animals that live there and their interaction with their physical surroundings.

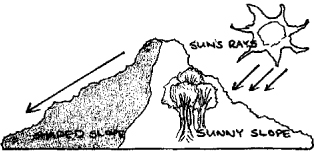

Ecosystems are dynamic. They change as species move in and out, the types of plants change over time, and the soil also changes. All of this results in continual disturbance, which drives the nutrient cycles and interactions within the ecosystem. This continual change is called succession.

Ecology succession takes disturbance, just like most things in life. We need to provide or undertake the right amount of disturbance and disruption to enhance biomass productivity. Disturbance even on a vulnerable and fragile landscape can ultimately result in successful healing of the land. This may include installing dams to harvest rainfall and thinning trees to increase light penetration to a forest floor and to the soil. While nature uses disturbance in successional changes in ecosystems, we can use disturbance in appropriate ways and at appropriate times to be innovative. On the other hand, too much disturbance can result in weeds and soil damage so it is an art to get that right balance.

Provided there is enough rain or irrigation, succession drives a landscape towards forest. Landscapes tend to be patchy as disturbances (fire, storms, even clearing) always occur and interrupt the successional process. New bare ground becomes covered by weeds.

The whole significance of this is that when we garden — plant our vegetables, flowers or other (useful) plants — we are essentially planting pioneers and creating a patchwork of mini-ecosystems all at different stages.

Furthermore, as we change our soils from clays and sands to loam, full of organic matter, weeds tend to become less prolific.

You may still get weeds but the type of weed changes. For example, cape-weed (Arctotheca calendula) and Patterson’s curse (Echium plantagineum) are common in calcium-deficient and infertile soil, but as we build healthy soil these very unwanted plants are replaced by fat hen (lamb’s quarters, Chenopodium album) or other “weeds” that are indicators of fertile soil.

It is quite clear that succession, for want of a better or possibly more appropriate term, occurs in soils too.

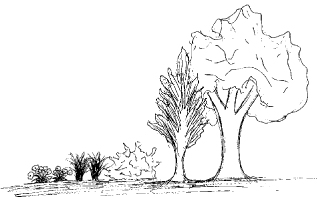

In essence, ecologically speaking, our backyards, which we enthusiastically tend and maintain, just want to grow up. So permaculture has always promoted the planting of the large climax, perennial trees and shrubs, as well as our annual vegetables.

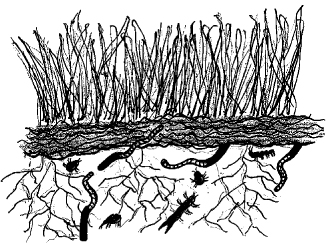

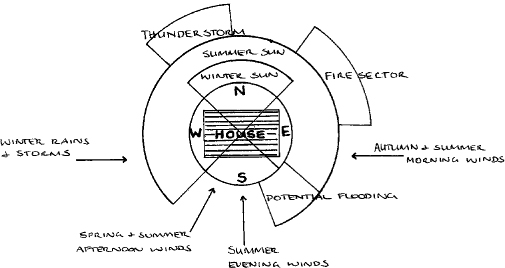

Different locations and aspects have different microclimates.

We strive to create a mature woodland or open forest, or even a rainforest in that climatic region, but what we end up doing in our backyards is more akin to a very young ecosystem that is never allowed to fully develop.

We install plant systems as a selective diversity — we determine what trees and shrubs we should have in our gardens, and in some cases this ad hoc combination may only work poorly, even with our aspiration of a “food forest” in the backyard.

As we continually harvest and remove edible plants, the many garden beds always remain ecologically unstable.

Forest ecosystems have many layers and components.

Once we understand all of this, we can implement more complex ecosystems. We can use different parts of the garden to create microclimates for the optimum growing conditions for particular plants.

Developing microclimate regions in our gardens is driven by the sun and heat. The soil heats up, light and heat are reflected, heat causes winds, and warm water evaporates and increases humidity.

In turn, plants that survive further contribute to the local environment — creating shade as they grow large, now reducing the air temperature even more, reducing evaporation from the soil, and new habitats are formed. It’s like the analogy of the woodland becoming the rainforest.

Permaculturalists should all become familiar with microclimate gardening as this is the key to successful guilds (see page 23) and successful production, as well as moving the garden to maturity.

Unfortunately, our annual vegetables are fast growing and productive, and then harvested typically within a year. The ground is prepared and another crop sown.

When we have fruit and nut trees and other perennial plants, such as herbs and companions, then our gardens go through a disjointed successional phase. Perennials continue to grow and spread but annuals are replaced.

Gardening like this, unfortunately, cannot be helped if we want to grow food. It is possible, of course, to grow more perennial vegetables, but this can limit our variety of foodstuffs. Most people don’t want to only eat the same vegetables all the time, so seasonal variation is preferable.

When planning a garden, it is not just a matter of drawing some garden beds and trees on a piece of graph paper. Truly functional, interactive gardens need thoughtful planning. However, as permaculture educator Toby Hemenway has said, “doing an imperfect something is better than doing a perfect nothing.”

Functional gardens can be formal, but formality is a human-imposed condition. Nature is pretty informal with large numbers of different varieties all intertwined, often growing in random spacing and arrangement. I am sure nature has rules, but probably not many, so we shouldn’t set ourselves a whole lot of rules and regulations when we design gardens.

We all know our climate is changing, and this may mean drying out in some areas and more flooding and rainfall in others. We need to design gardens that are resilient — that are adaptable to changing conditions, that are tough and hardy, that can be neglected and still survive and thrive — so design for catastrophe in mind. But don’t despair; if you give a plant the right conditions — soil type, water, sunlight and nutrients — it will grow. So everyone can grow vegetables as these are pampered plants.

The phrase ON SPECIAL helps us focus on what we need to consider before we start developing a property.

Before anything is started, observe your property. You need to understand the direction winds and storms come from in different seasons and at different times of the day and night; where water flows when it rains; what insects, birds, reptiles and mammals visit or live there; where the sun rises and sets as the seasons pass; how high the sun gets in summer and winter; where the frost line is located; what soil types you have; and what weeds you get each season, which may indicate the nature of the soil or any nutrient deficiencies there may be.

Site analysis is the most important step in your design. You need to consider the way the garden is exposed to the sun. Make the most of the sun when you need it and you may need to screen it at other times.

Look at the landscapes in neighboring yards as you may want to either screen the landscape or, perhaps, “borrow” a landscape so it becomes part of your garden. Existing vegetation in your garden may be retained, or you may want to remove it if it’s past its best.

Think too about the house as it’s such an important part of your design. It gives you your sanctuary and living space, and, of course, it gives you the entry point to the garden.

A thorough site assessment is crucial for successful gardening. Ideally observing wind patterns, rainfall events, water flow across the landscape, erosion, temperature of the soil, sun angles and areas of seasonal shade should occur over a year or more to build a picture of your local environment.

This is not always possible as many gardeners just want to plant when they get the urge, but observation and reflection can always occur at any time. You need to be able to respond to change and adapt techniques and planting schedules accordingly.

A needs analysis helps us focus on what our family members want, what plants and animals want or need, and what we need to do to protect and enhance our natural environment.

Write down things like what fruit and vegetables you like to eat; what herbs you use in the kitchen or medical chest; what colors you want to see in the garden; whether you want a compost pile or an earthworm farm, or both; consider chickens or other animals in the system; and so the list goes on.

It’s about growing and using abundant and healthy food — everything from herbal teas to fruit and vegetables. But what is the use of having a productive, edible landscape if you don’t use what you grow?

We expect a garden to evolve, and the human element will also change as our eating habits, tastes, and food processing skills evolve to cope with the surplus and successful yields of the landscape.

Sector planning mainly deals with the energies that move through the property. This includes sun angles, winds, storms, floods, fire and noise. The whole idea behind sector planning is either protection or opportunity. It considers protection from harsh sun, thunderstorms, noisy traffic, temperature extremes, frost, and natural events such as fire and flood. It grasps opportunities to harvest free natural energies (air, sunlight, water movement) to create a more resilient system.

For city dwellers, there seem to be few different sectors. You typically add visual (signs, buildings, blocking unwanted views) and social (organizations, other people, extended family). Obviously, noise (traffic, workshops, retail outlets) plays a larger role than in a rural setting.

Permaculture designers place every component (see Elements next) in a region called a zone. Zones are imaginary lines around a house and property.

There are five zones, and all elements are placed according to how often we need to visit — with vegetables and herbs, which we use every day, in zone 1 closest to the house, and fruit trees, which we visit seasonally, further out in zone 2 or 3.

No, we are not talking about the chemical elements you learned about in school. Everything we place in a design is called an element, so this includes plants, sheds, garden beds, ponds, trellises, chicken pen, compost pile and so on. And don’t forget about the entertainment area, the gazebo or pergola and barbecue.

We endeavor to match and group elements together so that the products of one element may become the needs of another.

For example, the manure from chickens is used to feed the earthworms or add to the compost heap, so it makes sense to have the worm farm and compost area close to the chicken pen.

While it is important to grow as much food as possible, don’t think that this is all you should grow. Recognize that some plants are grown to help with pest control, a shady tree to sit under, others because they smell nice and look attractive, some to protect sensitive plants (nursery trees) and some to attract predators or pollinators.

A sector plan highlights the movements of energies through the system.

In many ecosystems every plant has a role to play, so when we design a garden try to mirror these ideas. It’s all about balance.

Every plant and animal likes company, and some combinations and relationships seem to benefit all involved.

This assembly of organisms and parts of their habitat or collections of interacting, networking components is called a guild.

Common companion planting where combinations of vegetables and herbs are planted close to each other is a good example of a guild.

We’re not too sure about how some guilds work, but we recognize that many plants struggle to get going. Having a nurse or chaperone plant nearby to protect vulnerable seedlings and to create ideal growing conditions for the seedlings will ensure greater survival.

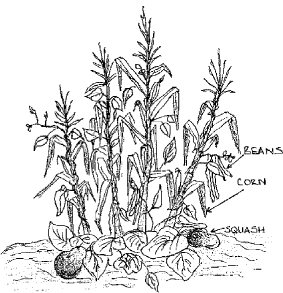

We just need to work out the right guilds — the right relationships and combinations of plants and elements that are mutually beneficial. The classic example of a guild is the famous “three sisters” of Native Americans:

• Corn — is the trellis (growing frame) for beans. This is planted first and when the corn seedlings are about 6 inch high the other seeds are planted, sometimes together, sometimes separately.

• Beans — are nitrogen-fixing. Bean seeds are often planted later than squash as they are fast growing and they need corn to become established before they start climbing.

• Squash — shades the ground and suppresses weeds.

In North America, a fourth “sister” is often added, the bee plant (Cleome serrulata), which attracts beneficial insects for pollination (for beans and squash, as wind pollinates corn) and has edible leaves and flowers. The Incas from South America also added amaranth, which is a grain and useful dye.

In other parts of the world common herbs such as borage (attracts predatory wasps and bees for pollination, edible flowers) or perennial basil (butterfly and bee pollination, edible leaves) substitute for bee plant.

Example of companions — the “three sisters” of corn, squash and beans.

There are many other good examples of guilds and companions, and these combinations of elements are a crucial design idea that we all need to adopt.

So, let’s focus on implementing noncompetitive guilds and resource sharing when we endeavor to develop functioning and beneficial gardens. For example, we should underplant fruit trees, such as apples and lemons, with comfrey, borage, fennel, yarrow, and non-climbing (shrub-like) beans or peas. Nasturtiums can be used as ground cover, but so can nitrogen-fixing perennial clovers and alfalfa. It’s probably not so wise to have tall plants under our fruit trees.

The main concept here is that not all plants in a garden have to be edible. We need a mixture of plants in this artificial guild to provide different functions: grass suppression; food for insect, bird or mammal pollinators; nutrient accumulation; mulching plants; nitrogen fixers; pest repellents; soil fumigants (nasturtium, marigolds); and soil building.

We also have plants to create habitat, attract and protect large predators, and provide shade and shelter. For example, yarrow and comfrey are high in minerals and have medicinal functions, while borage and fennel attract pollinators and predators, and both have edible parts.

While garden guilds are designed by humans, you wouldn’t put all of these plants under a lemon tree. It’s a deliberate assembly of plants that we choose to grow in the belief that we are mimicking a community in nature.

Even so, in disturbed bush or forest areas we often see exotics amongst native plants. Interestingly, they all seem to flourish, and this suggests that nature uses whatever plants it requires to fill the niches in that ecosystem. Nature doesn’t distinguish between natives and exotics, unlike some humans who fixate on exotic removals in the belief that nature will suffer if we don’t.

Under the umbrella of “companions” we need to include pest control, and design for scented walkways, pest-repellent herbs and predator attracting plants (tansy for ladybugs, yarrow and fennel for hoverflies and wasps), as well as plants to attract bees and butterflies for pollination.

Generally, beneficial insects are either predators, parasites (parasitoids), pollinators or weed feeders, but let’s focus on predators.

You always need to have a few pests around to encourage predators so that the response time between pest attack and predator dining is reduced. You should use host plants to always maintain predator species in the garden, and these include buckwheat, coriander, clover, fennel, lemon balm, parsley, Queen Anne’s lace, yarrow and tansy.

As part of this strategy it is also important to leave some herbs and vegetables to flower and set seed. Besides the obvious idea of saving your seed, this encourages predator adults, such as hoverflies and lacewings, to feed on the nectar and pollen and lay their eggs on the plants. It is often the larvae of the species that are the real predators and these devour aphids and other sap-sucking pests as they grow.

Water is essential to all life, and if we want to grow plants or keep animals we need water. When planning a garden think about how the plants will be irrigated. You might choose to hand-water, but ideally having an automatic watering system is best. Dripline, individual drippers and water-efficient sprinklers are all suitable and some of these components are discussed later in chapter 10.

Think about how you could include and incorporate stormwater, rainwater and graywater as strategies to water gardens and the landscape.

Assets are the resources available and materials required for the project. Resources can be:

• Living — plants and animals. What you have already, what you can easily source, what may be available at the local nursery.

• Structures — building materials, rocks and timber. Is there timber that can be milled on-site, rocks that can be used for retaining walls, or a local farmer who has straw for the walls of buildings?

• Energy — wind, wood, water (and machinery to do work). Are there opportunities to harvest or generate electricity or other forms of energy in some way?

• Social — people and their skills, suppliers and consultants. Who is a local “expert” you can call on to help with plant selection or breeds of chickens or grafting techniques?

• Financial — what money is available to purchase labor, machinery or materials? Can some materials or plants be bought with LETS (Local Employment [or Exchange] Trading System) and other alternative schemes? Is there potential income from the sale of goods and services?

Professional landscapers will often produce a bill of quantities: an itemized list of what is required for the project, with specifications for some components, and often anticipated costs so that a budget can be determined.

Aesthetics is about beauty, so think about flowers, foliage, color, and the visual setting (pretty view).

This considers soil, topography, aspect and slope. Paths and access tracks or roads can be listed here too. Topography refers to terrain — how rough, steep or slippery, or whether it is rock-laden, a gravel pit or just sand. Aspect is about orientation to the sun (and direction). Some slope on a property is good, but there would be some instances when the slope is too steep for vehicles, houses and any cultured ecologies.

As mentioned already, soil is discussed in detail in the next chapter, as this is the key to ecosystem yield and growing healthy and safe food.

Designers need to ensure that gardens and places connect with the inhabitants and engage them. If this doesn’t occur they won’t stay in the garden.

The designer’s mantra is that we’re in it together, helping each other. Everyone counts, everyone has a say, so that everyone has ownership. It is not just the designer but all family members have to be involved.

Producing a design or plan is generally undertaken in a number of steps, involving the client in some stages, and just the designer or design team for the rest. Think of the acronym SPEER.

Further to what we discussed earlier, particular species should be selected with climate, growing conditions, soil type, temperature extremes and growth habit all in mind. While a client may desire a particular fruit or vegetable, and maybe we could obtain them from a nursery, you may find that some plants just won’t grow in that location.

Good planning involves visioning and patterning. You need to be able to imagine what a garden or property will look like as you undertake a design. The “design” is not only artwork, but it is also a representation of a functioning cultivated ecology. Permaculture designs can be full of patterns. Patterns are all around us in the shapes of honeycomb, the arrangement of seeds in a flower, the spirals of galaxies, the flow of water across a landscape, the eddies of winds, and the crystals of water in snowflakes.

Some permaculture designers might acknowledge the patterns in nature by drawing in mandala gardens, herb spirals and circle gardens; but none of these, I might add, are necessary in any permaculture design.

Planning a garden also requires commitment. You need to look after all living things and make the time to ensure they are watered and fed, pruned and mulched — even transplanted to another area if they appear to be suffering — and pests and diseases controlled. I don’t think gardeners really appreciate the amount of time that is required to ensure their little ecosystem is humming along just nicely.

Any garden plan or design has to be done to scale. The usual way to do this is on graph paper (A3 at least) and have lots of cutouts and shapes of garden beds, structures (sculpture, artwork, trellises, sheds), trees and anything else you want in the garden (playhouse, barbecue, rainwater tank, scented garden).

Garden beds can be of any shape. Square or rectangle beds give the impression of sharpness and formality, rounded or curved beds seem softer and send an invitation to meander through the garden. At the end of the day, it’s about how you feel in a garden or space, and what combinations of elements seem to work.

Over time gardens change. You put in a trampoline or small pool, then remove these when the kids have grown up and left home, a tree once planted for shade now takes up the whole backyard and must be removed, or some fruit trees and other plants reach the end of their lifespan and die. When you are designing in those early stages try to plan for the future. Obviously who knows what the future holds and what changes you want to make in the garden, but at least plan for access and contingency. Leave a path wide enough for a small machine to come and help with plant removal or bringing in soil and mulch, or to enable a rainwater tank to be rolled around to the back. Don’t fill every space unless you are happy to remove any plants to enable access or you are sure that what you are building will last forever.

Once an initial draft has been done (artwork and report), then this is shown and discussed with the client who will be able to provide some feedback about what they like and what they would like to see changed.

This enables you to make amendments and work towards the final design and report. Of course, what is finally produced will, no doubt, pass through many stages and many meetings with clients. Ultimately, there may be tradeoffs between the client wants and the needs of the other organisms in the ecosystem and the environment itself.

Executing the plan is implementing the design. It is rare that a whole design is built at once, and the most common implementation is spread over months and, more usually, years. This is where you need to set a schedule of works, with realistic goals and a workable budget.

This is really reevaluation, where changes to the design are made before building begins or changes made during implementation are recorded.

It allows you, as a designer, to critically examine what seemed to work, what needed to be changed and what should be discarded. Too often designers put in particular plants, structures and garden bed shapes, simply because they want them included or in the belief that as these things worked before they should work again here.

The design always has to be what is best for the clients, the site and the environment.

Once you have a design for the property the next step is building it. Think of the acronym PERFECT, where each letter indicates an important part of this process.

This includes buying or obtaining their personal choice of fruit trees or vegetables, and what you want to plant first. It is also about pre-lays for irrigation, marking out paths and structures, and building some of these as required.

Not everyone has a big backyard to grow their own food, and not everyone lives in a passive solar home. So if you have some garden area you may be faced with a choice — do I grow some food or do I plant to cool my house. Well sometimes you can do both, using deciduous fruit trees for summer shade and food and climbers, like kiwifruit, cucumbers and pumpkins, strung over a trellis or some structure to protect walls from the hot summer sun.

While there is great joy and satisfaction when you grow some of your own food, it may be better to focus on being comfortable in your home and reducing energy bills for heating and cooling.

Our aim should be to build soil and to repair the land. One of the ethics of permaculture is “care of the Earth” and this has always been the foundation on which the philosophy and principles are based.

These are the materials available for use, to build structures (trellises, propagation tunnels, sheds, retaining walls), to fill garden beds (compost, soil, mulch) and to plant (what herbs, trees and shrubs you have assembled already or are willing to buy). Using, accessing and assembling resources is an art in itself.

Most things you want to implement cost money. You should determine a budget, but allow for contingencies, as often projects seem to take longer and cost more than you had set aside. While you can scavenge lots of materials from roadside pickups, neighbors and friends, and obtain many things for free or for “green” dollars through LETS and freecycle networks, you may still have to pay for contractors, machinery and some building materials.

These are the landscape changes that are undertaken and include drainage, mounding garden beds, putting in a driveway or access track, running power to a rear shed, burying reticulation pipes, clearing an area of vegetation, leveling a site, shaping a pond and laying hardscaping (hard surfaces such as roads and parking areas). Earthworks are normally undertaken early in a project, and if you have a machine available, use it.

Machinery is often used for earthworks — digging trenches, moving soil and so on.

These are mainly seasonal issues, such as availability of bare root fruit trees, planting schedule (best when rain season is about to come) and weather at the time (who wants to work in the rain, stand in the hot sun all day and go out on a frosty morning?). You need to also consider the availability of electricity to power tools, water to mix concrete or soak plants, and access (do you need a four-wheel-drive vehicle to get to the rear of the block?).

Sometimes you need to rely on tradespeople and contractors to undertake trenching for the pre-lay of irrigation pipes or running power cable and conduit for pumps, a licensed plumber to connect your graywater system, an electrician to install a power point near the pond to operate the fountain pump, a concrete finisher to float the floor of the new shed, and a stonemason to build a rock wall or limestone block wall.

At other times, you just need advice on the schedule of works, where to place a rainwater tank, what size pump you would require to irrigate the gardens, and what trees should be removed from the property to have good solar access.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Many deciduous fruit trees can be ordered and collected as “bare root” plants. This is because these plants are dormant in winter, and can be literally dug out of the ground, transported and then replanted with great success.

Here are some hints about getting a garden up and running and to make it something special:

• In small urban lots it is impossible to grow lots of fruit trees. However, if you become friendly with your neighbors, you might find them happy to share what they have and you plant what is missing to supply them in return. Your neighborhood becomes your orchard.

• Plant a number of native plants (preferably indigenous to your area) as these will attract wildlife: nectar-producing species to attract butterflies, insects and small birds; grasses for reptiles (lizards, skinks and geckoes), which will help with pest control; and emergent macrophytes (reeds and rushes) near a pond for frogs.

• Provide hollows, logs, piles of rocks and sunbathing spots for lizards, and a garden pond for frog habitat. A water supply is crucial to attract wildlife — water is a life magnet.

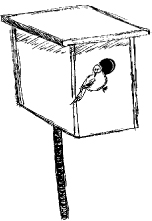

• Install a few nesting boxes in the taller trees on your property. Many birds and animals that use nesting boxes exist on a diet of common insect pests.

Place nesting boxes as high as possible — away from predators. Make sure no direct sunlight or rain can enter. Monitor the box to ensure that bees and feral birds do not take up residence. Secure firmly to the tree.

Building plans for boxes are easily obtainable, as the entry hole needs to be a particular size for each bird or mammal species. Never paint the inside of the box and only use nontoxic paint on the outside.

Provide nesting boxes to encourage wildlife to visit.

However, there is no guarantee that nesting boxes will be used by the desired species, but having birds and mammals to view is enriching for the soul.

• Build some garden beds on themes. These include a pizza garden (herbs used to garnish and flavor a pizza); the scented garden; a senses garden — to see, hear and feel (plants based on smell, texture, color and sound, e.g. leaves rustling in a breeze); and play — children having their own vegetable garden, trees they can climb or plants to attract butterflies.

• Borrow a view. Wouldn’t it be great, sometimes, if we didn’t have fences between properties?

Your garden would blend into your neighbors. The large majestic tree next door would become a backdrop for your understory garden nearby. When planning your garden use the views and features of adjoining properties to extend your own.

• When laying out the garden areas, use spray paint, string, small rocks or pavers to mark out beds and paths. This enables you to have a good look at what the garden area will look like, and allow you to make any changes before all the fun begins.

• Active children need to be kept active. They can collect eggs, feed earthworms, climb a tree or up into a tree-house, swing, play in a sandpit, or throw balls through a basketball hoop.

• If there are no children nor any prospect of children in the house, some other household members can perform some of these tasks such as feeding chickens and earthworms.

• Take over the curbsides! What an under-used space in most suburbs.

Borrow a view from a neighbor’s garden.