Some plants have adaptions to minimize water loss from their leaves, such as the spines of cacti. The spines are modified leaves.

ALL ABOUT WATER |

10 |

WATER IS LIFE. We take it for granted, but every home needs to use water wisely. There are so many ways in which we can harvest water, treat it, recycle it and use it in our homes and gardens.

The message to gardeners is very simple — it’s time for a fundamental change from the traditional ways of gardening.

The water wastage has to stop and there are gardeners who are treating our scarce water with little respect. We need to change our behavior and give clean freshwater its true value.

Water restrictions will continue in many places and freshwater availability will continue to fall throughout many parts of the globe in the years to come.

Let’s plan and plant a water-responsible garden to help avoid a water catastrophe. Let’s become smarter gardeners by examining four general areas where you could make a difference: water conservation, irrigation practices, graywater reuse and rainwater harvesting.

We need to learn to minimize water consumption and maximize water efficiency. Water conservation is all about ways to save us using clean town water by reducing the volume we use each day, as well as minimizing water loss through evaporation, spillage and downright neglect. Here are some handy hints.

To minimize water loss:

• Cover pools and outdoor spas.

• Use mulch in the garden — whether this is living mulch, dead plant material or other materials such as rocks or plastic sheeting.

• Add compost and organic matter to the soil to help retain water. Healthier plants are also more able to withstand drought.

• Use shady trees to protect ponds, soil and understory plants.

• Use drip line irrigation or porous (sweat) hoses to deliver water to the root zone rather than overhead sprays where wind can blow a lot of the water away.

• Add water-holding amendments to soils, such as compost and organic matter, and mineral-based amendments, such as bentonite and kaolin clays, for sandy soils.

• Water your plants either early in the morning or late in the afternoon.

• Repair leaks — a rapidly leaking tap could waste between 12–25 gal a day.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Got a leaky tap? Dripping at only one drip a second adds up to nearly 3 gal every day and if left for a year would waste about 1,000 gal: enough water to clean your teeth 14,000 times.

To minimize water demands:

• When building new garden beds, group plants that have similar water needs (hydrozoning).

• Plant drought-tolerant plants in the garden — natives and succulents, Mediterranean herbs such as lavender and rosemary, and fruit trees such as olive.

• Improve the soil. Increasing organic matter allows more water retention and more water availability to plants.

• Reduce your lawn area.

• On large garden areas it may be economical to install some water moisture sensors to activate irrigation systems. In this way, only the amount of water that plants actually need is supplied.

• Avoid washing your car on the driveway; position it on the grass instead.

• Plant windbreak trees and shrubs to reduce evaporation from the soil.

• Install a graywater reuse system, reusing wastewater from the laundry or bathroom.

• Sweep paths instead of hosing them down.

• Install permeable paving rather than solid slabs or pavers. Rainwater can move through the permeable paving into the soil.

• Take shorter showers.

• Fit water-efficient showerheads.

• Fit water-efficient aerators or flow regulators.

• Replace toilets with at least a 1.6 gal/0.8 gal dual flush — and use the half flush whenever you can. Placing a brick in the tank is an easy and economical solution.

• Use the washing machine only when it is fully loaded.

• Fit a pressure reduction valve to reduce pressure in the town water supply.

• Purchase a front-loading washing machine. These tend to use about half the water of a top-loading machine, i.e. 13 gal instead of 21–25 gal per cycle.

• Install a rainwater tank and use this water to flush toilets and provide a laundry source.

Some plants have adaptions to minimize water loss from their leaves, such as the spines of cacti. The spines are modified leaves.

Undertake a water audit and estimate your household’s total water usage. Monitor the duration of showers, estimate bath volumes, record the number of loads of washing per week, and determine how much water goes onto the garden, how much on toilet use each day and how much is used in the kitchen. Work out how much you could cut down to see how your consumption could be reduced. Aim for 50% reduction.

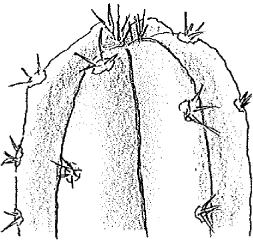

Some plants have small hairs that cover the surface of a leaf to reduce transpiration. Also shown are the stomata (like eyes) that close during the hot part of a day.

» DID YOU KNOW?

On average, approximately 4,000 gal a year can be saved in homes by replacing inefficient showerheads, installing tap flow control devices and fixing leaks, while a further 5,000 gal a year could be saved through a retrofit of inefficient toilet suites.

Approximately 13,000 gal a year can be saved by replacing a well-maintained lawn (turf) with a waterwise garden.

Water shortage and high energy costs motivate gardeners to harvest the greatest possible yield from every precious drop of water.

A waterwise garden can be achieved by either installing an efficient watering system or replacing lawn and other water-hungry exotics with waterwise plants, or both.

Designing your home’s irrigation system to be waterwise would not only conserve water but also save you money on your water bills. Most people who have automatic systems rely on sprinklers and sprays. The trend these days is for dripline systems.

In many cases, contemporary spray and sprinkler irrigation systems can be extremely wasteful of water. Some are not very environmentally friendly, they may increase the risk of plant fungal diseases, and they are inflexible and ill-suited to complex garden layouts. Choose sprinklers that produce large droplets and are water efficient.

Furthermore, landscape-sensible design will enable reduced fertilizer use, and reduce runoff and thus soil loss. Coupled with an appropriate use of mulch, organic compost and soil amendments, your garden will still thrive on reduced water use.

A low-irrigation garden should result in:

• reduction in water demand

• minimization of runoff, and an increase in water absorption into the soil

• replacement of scheme (town) water with stormwater, rainwater or graywater

• efficient irrigation of plants

• lower evapotranspiration, by the use of mulches and substrata or subsurface irrigation methods.

Proper watering methods are seldom practiced by most gardeners — they either under- or over-water.

The person who under-waters usually doesn’t realize the time needed to adequately water an area and the volume required by growing plants. A light sprinkle on plants is harmful as insufficient water is made available to the plant. Light sprinkling only settles the dust and does little to alleviate drought stress of plants growing in hot, dry soil.

Generally, it is best to water the garden area for a longer time, but less frequently. A good soaking is far more effective. This type of watering allows moisture to penetrate into the soil area where roots can readily absorb it. A deeply watered soil retains moisture for several days. However, the watering regime does depend on the type of soil. For example, you should water more frequently on sandy soils and less frequently on clay soils, but over-watering on deep sandy soils is not advised as the water quickly passes through the root zone downwards and is not able to be absorbed by plants.

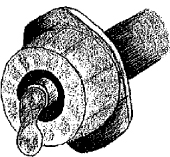

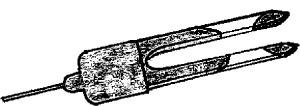

Individual drippers emit a set amount of water each hour.

Then there are those people, with the best intentions, who water so often and heavily that they drown plants. Symptoms of too much water include leaves turning yellow or brown at the tips and edges, then brown all over and then dropping from the plant.

Dripline irrigation contains embedded drippers at regular spacing inside the tubing.

Too much water in a soil also causes oxygen deficiency, resulting in damage to the root system. Plant roots need oxygen to live.

Thoroughly moisten the soil at each watering, and then allow plants to extract most of the available water from the soil before watering again.

Gallons of water/tree/day while in production |

Gallons of water/tree/day for survival |

|

< 6ft |

13 |

3 |

6–15 ft |

40 |

5 |

> 20 ft |

100 |

18 |

Table 10.1. Water requirements of trees.

Determining the amount of water to apply to trees is probably one of the most difficult questions to answer. Many factors must be considered, such as the soil type, environmental conditions, the nature of the specific crop, the size of the tree and time of the year, e.g. sandy more than clayey soils, summer more than winter and spring, fruiting more than general growth, wind more than still air etc.

You might be surprised to discover the amount of water some trees require, as shown in Table 10.1. Frugal gardeners tend to under-water fruit and nut trees and underestimate how much water they will need each year to have a productive food garden.

The secret is to make sure that plants get the right amount of water, when they require it. This involves monitoring and observing. There are many different devices available for determining the soil-moisture status in the garden. These include tensiometers and gypsum blocks.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Only about 1% of the water a plant obtains and uses is retained in the fruit, and less than 0.5% in the remaining parts of the tree — the leaves, shoots and roots. The other 98.5% of the water supplied to the tree is lost by transpiration.

A typical fruit tree contains about 85% water and 1% inorganic nutrients (fertilizers), while the other 14% is made up of sugars, starches and other organic compounds.

The amount of water used by plants increases:

• as the air temperature rises

• during dry windy weather

• when soil temperatures are high.

Gardening can be complicated, can’t it? It doesn’t have to be, and we can easily improve our irrigation understanding and skills.

For example, different watering regimes have different efficiencies (a measure of how much water is used compared to how much is wasted), such as:

• surface water use, e.g. furrows 60–75% efficiency (25–40% of water is wasted)

• spray 65–75%

• drip 75–90%.

I suppose the more basic question to be addressed is, “Why do we need to change?” Besides the increasing cost of water and power, depletion of our water resources and pollution of our water bodies, there are pressing demands for more efficient systems and a need for safer ways of reusing our graywater and collected rainwater.

Drippers are by far the most efficient way to water plants. Individual drippers typically come in 0.5, 1 and 2 gal/hr, while dripline drippers vary from 0.3–2.5 gal/hr.

Furthermore, technology is such that drip irrigation can be pressure-compensated, self-flushing, anti-siphoning and have a shut-off mechanism. A pressure-compensated dripline may have drippers emitting 0.5 gal/hr while a non-compensating dripper could be 2 gal/hr.

A drip irrigation system is easy to install and is economical, and is not as complicated or as costly as you may think.

With any type of irrigation system there are pros and cons. In this case, the pros certainly outweigh the cons. The benefits of drip irrigation include:

• efficient water use (uniform distribution, good recovery)

• low application rate (reduced risk of runoff)

• ideal for odd shapes and narrow strips

• improved disease control

• effluent (e.g. graywater) reuse

• reduces weed growth

• watering over a longer period is possible

• reduces exposure to vandalism

• reduced injury risk

• more energy efficient

• ability to better use fertigation (injecting fertilizer into the irrigation network).

On the other hand, drip irrigation does have some drawbacks, which include:

• requires capillary action of water to work

• more technical maintenance required

• establishment of lawn may require temporary overhead watering.

In some cases, drippers or dripline may need replacing after 3–5 years if they become blocked. You can minimize this by using dripline and drippers that can be flushed, using copper drippers to prevent root intrusion or having a mild herbicide dosing system to stop roots from entering the dripper pores.

• Water in the early evening or night, thus reducing loss by evaporation. About 60% of water is lost if you use fine sprays during the heat of the day — the water either never touches the soil or quickly evaporates as it does.

• Water the roots. How many times have you seen someone watering plant leaves? Leaves do not absorb much water this way — it mainly enters the plant via root uptake.

• Turn irrigation off during the winter months (or whenever you experience your main seasonal rainfall). Generally, irrigation can be turned on from spring through to autumn, and then it should be controlled so that if rain events do occur the irrigation system is not activated.

• Don’t water paths and driveways. Overspray is a complete waste of precious water. Make sure your system is set up to deliver the right amount of water, at the right time, to the right place.

• If you must use sprinklers buy ones that produce large droplets to minimize wind drift. Only use micro-irrigation for intense garden beds that need humidifying and are sheltered and protected from wind and sun.

• Don’t over-water. Every soil type only holds a certain amount of water, so regulate the volume you add. Even a simple and inexpensive tap timer on manually operated sprinkler systems helps.

• Consider hand-watering, which can be both relaxing and efficient, especially if you have a trigger nozzle that only allows water to leave the hose when it is pressed.

• Over-watering can often occur if the water pressure is high. You can install a pressure-reducing valve to keep the water pressure as low as possible to reduce water wastage.

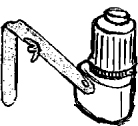

• Installing a rain sensor will also prevent over-watering. These devices monitor or respond to either rainfall or soil moisture and prevent the controller from switching the irrigation on.

Common types of sensors include tensiometers, gypsum blocks and capacitive sensors. Evapotranspiration sensors are relatively new products that can monitor changing weather conditions, even when there is no rain and adjust the watering regime daily.

Rain sensors vary in price, but are typically about half the cost of a soil moisture sensor.

Heavy droplet sprinklers reduce loss by wind. Notice the overlap of spray.

» DID YOU KNOW?

If you use a high-flow dripper (e.g. 2 gal/hr) much of the water is lost to plants as it tends to move downwards quickly, especially in sandy soils.

When a low-flow dripper is used (e.g. 0.4 gal/ hr) it drips slowly enough for the applied water to spread sideways as well, ensuring that water is kept in the top soil, and is therefore more available for plant uptake.

The disadvantages of low-flow drippers are that you typically need a high pressure pump to make them work (as they are pressure-compensating) and secondly the pump is on longer, so operating (running) costs are higher.

Rain and soil sensors can prevent over-watering.

Graywater is the wastewater stream from all sources other than the toilet (toilet water is often called blackwater or sewage). Kitchen graywater (and dishwasher water), however, should not be reused as this can contain oil, fats and food scraps, which do not break down easily and can easily clog irrigation filters and pipes. This means that householders can easily reuse greywater from the bathrooms (shower, handbasins and bath) and the laundry.

Graywater can be reused in a variety of ways, such as watering garden plants and for toilet flushing, which requires the installation of a treatment system. Watering our gardens with graywater can be easily achieved.

Water is too valuable a resource to waste, and any endeavor to reduce freshwater consumption or reduce wastewater disposal and treatment and the energy this consumes should be encouraged.

Typical values for the volume of daily graywater produced range from 20–25 gal per person, so reusing graywater onto the garden could give a family of three or four an extra 25,000 gal of free water a year.

Reusing laundry and bathroom wastewater on your garden is just another way of moving towards a more sustainable lifestyle. What’s more, it’s a practical step that is just as easily applied in the suburbs as it is in the country.

Graywater can be reused in a number of different ways. These include subsurface drain systems and substrata dripper irrigation for plant irrigation.

There are now many different graywater systems approved for use, but you often need to submit an appropriate application and fees, typically to the local government council. A licensed plumber is required for any changes to the sewerage system.

Graywater cannot be used to irrigate a vegetable garden that contains below-ground food crops such as onions, potatoes and carrots, but can be used on above-ground crops such as tomatoes, broccoli and corn, and on fruit trees, lawn areas and on other plants such as exotic and native shrubs and trees.

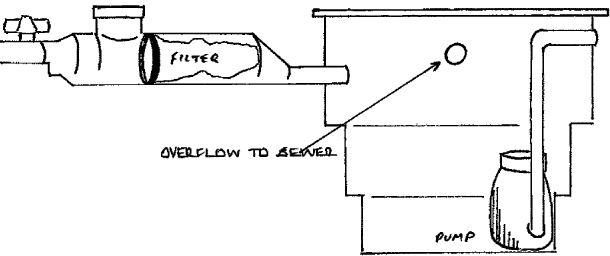

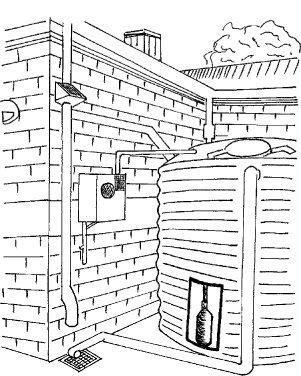

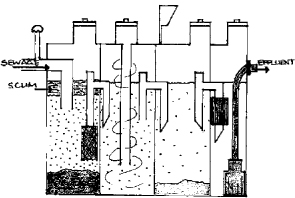

An example of a graywater system — a filter and pump tank

Placing graywater in the root zone of plants is the most effective way to ensure maximum uptake of both the water and the range of nutrients that are available in graywater. A word of caution: many Australian native plants are susceptible to high levels of phosphate. These include the family Proteaceae, such as grevillea, banksia and hakea. Some introduced (exotic) plants, such as azaleas, camellias and gardenias, do not like the alkaline nature of some gray-water sources. It is best not to use graywater on any of these types of plants.

Graywater should first pass through a filter or settling tank before dispersal in an infiltration area. The filter or tank removes coarse material, such as hair, soap flakes, sand and lint, which could block the drippers, draincoil pipe or soil.

Dripper systems are the most common. Depending on the slope, you can gravity-feed the graywater to the drip irrigation or you may have to pump it to garden areas. Pumping water is always more expensive, but it gives you more flexibility, and you can send the recycled graywater to any garden bed on the property.

• Select garden friendly detergents. Only biodegradable products and products with low phosphorus, sodium, boron, chlorine and borax should be used. Bleaches and fabric softeners should be used sparingly.

• Apply graywater in several locations rather than one single point, so that pooling of graywater does not occur.

• Apply graywater to areas that are not readily accessible to children and household pets.

• Don’t use graywater from the washing of diapers and soiled clothing.

• Don’t use graywater when a household resident has an infectious disease, such as diarrhea, infectious hepatitis or intestinal parasites.

• Don’t discharge graywater on edible plants or where fruit fallen to the ground is eaten.

• Don’t store graywater. Stored graywater will turn septic, giving rise to offensive odors and provide conditions for microorganisms to multiply.

• Don’t over-water, which can result in the development of unsightly areas of gray/green slime. This slime is caused by the presence of soaps, shampoos, detergents and grease in graywater. The accumulation of slime can cause odors, attract insects and cause environmental damage.

Graywater contains a range of pathogens, those organisms that may cause disease. Graywater is not allowed to be used in ponds or for above-surface irrigation systems due to the risk of mosquito breeding and contact with human skin and possible pathogen transfer.

Many pathogens such as bacteria (e.g. fecal coliforms) and protozoans (e.g. Giardia) may be present in some graywater sources.

Graywater also contains bacteria and other microscopic organisms that feed on the nutrients in graywater, causing the wastewater to smell after a day or two.

High levels of nitrate and phosphate may be beneficial to many plants, but can be detrimental to humans if ingested.

Our rainfall patterns and our climate are changing, and this is all part of a larger global picture, but we all need to plan for changes happening locally.

The average home could easily harvest thousands of gallons each year from their roof, and this water can be used to offset the water budget for your home.

Installing a rainwater tank, no matter what size, is a small step that you could take to become self-reliant.

Generally, the larger the tank the more water you can collect and use. If you wanted to use rainwater to flush toilets and provide water to the laundry, then you would probably need at least a 2,000 gal tank. It is not uncommon to install 7,000–12,000 gal tanks for this purpose, but all of this depends on your annual rainfall patterns.

» DID YOU KNOW?

To calculate how much rainwater falls on your roof, multiply the annual rainfall (in meters) in your region by the roof area of the house. For 1m2 of roof and 1mm of rainfall, 1l can be harvested, so, for a 200m2 roof area and annual rainfall of 500mm (0.5m), this equates to 100m3 = 100,000l each year.

If you use the imperial system, multiply the roof area in square feet by the number of inches of annual rainfall, and then multiply the result by 0.623. For example, a roof area of 2,000 square feet and an annual rainfall of 18 inches equates to 22,500 gallons (about 100,000l).

Collecting rainwater has many environmental benefits, as well as benefiting you! Some reasons for harvesting rainwater include:

• making freshwater available to flush toilets or to provide a laundry source

• using rainwater for drinking purposes

• supplementing the watering of garden areas

• reducing our use of town water — a very valuable, limited resource

• saving some money — buying less water from a service provider or utility

• providing a water source that has reduced levels of salts and other substances.

Rainwater tanks are now made from a variety of materials. Generally, the most popular for urban backyards are either made from steel or polyethylene.

Large tanks (12,000 gal plus) are typically steel-liner tanks. These have a steel outer structure with a flexible poly liner inside.

These days, poly tanks are UV stabilized and come in a range of colors. Both steel and poly tanks normally have at least a 15-year warranty.

If there is space below the house or veranda then a bladder tank is an option. These tend to be proportionally more expensive, but can be ideal if there is little room for a regular tank.

Finally, more and more tanks are being buried as new homeowners build larger houses on smaller blocks. Below-ground tanks can be buried under decking provided there is access to service the pump or to clean out the tank if required.

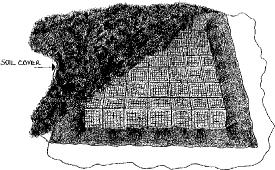

Buried tanks can be one-piece poly or concrete tanks or interlocking plastic cubes wrapped in a poly liner. These latter types can be almost any size and shape.

Some rainwater tank systems are suitable for burial, and the storage “cubes” are wrapped in a waterproof fabric.

Most people want to use the rainwater — either for drinking, to flush toilets or to wash clothes. Rainwater is most often pumped to the house, although gravity can be used in some cases to direct rainwater to fixtures in the house. Either a submersible pump, a pressure-tank pump or a pressure-switch pump is used to supply rainwater when required.

When the tap is turned on, or the toilet flushes, the pump is activated and gently pumps water to fill the tank, or enter the kitchen sink or washing machine.

If you wanted to use the rainwater for watering the garden, then think about how much water your plants actually need to survive.

If you work on 0.5 in of water every fourth day applied to the garden then you can calculate how much water you require. For example, if the garden bed is 400 ft2 (say 20 ft × 20 ft) then you require 100 gal. So, a 200 gal rainwater tank would only last for one week (two waterings).

It is always best to install the largest tank possible, keeping in mind the size restrictions you may have at your home and the cost. You don’t really need to water the garden in winter, so you should work on summer watering only.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Using 0.5 in as the preferred plant watering regime, this equates to 2.5 gal of water for every 10 square feet of garden.

If you only install a small tank (e.g. less than 5,000 gal) then it is likely you will run out of rainwater during the summer period. This, of course, depends on the uses of the rainwater and whether your area experiences summer rain to top up the tank. Providing a full laundry, kitchen and bathroom service rapidly depletes the volume you can collect during rainy times.

Rainwater tank systems can be set up to integrate the town water source with the rainwater source. An automatic water-sensing device enables town water to enter the system when the rainwater is depleted. There are several ways to achieve this, from manually changing valves to fully automated switching devices. It is important to always have water to flush toilets and to provide a source to the laundry.

Most rainwater tanks come supplied with a basket (leaf) filter, tap and overflow pipe. In addition to these standard fittings, a number of optional extras are available for your rainwater tank system. These include:

• First-flush device. This enables the first rains to be directed away from the tank. This water may contain dust and decayed matter, and it is best not to collect this and pollute the tank water.

• Vermin proofing. This is often necessary for steel and steel-liner tanks to prevent insects, frogs and small rodents from finding their way into the tank.

• Garden overflow. Either a subsurface piped trench or a simple gravity-fed dripper system is installed to direct overflow more effectively to garden areas or beds.

• Leaf eater. This is a screen that filters rainwater and allows leaves to be shed from the system.

A typical rainwater tank setup includes a first flush, leaf eater, water-switching device and overflow pipework.

Rainwater tanks are relatively cheap. However, small tanks are proportionally dearer, so the larger the tank the more cost-effective it is. If you intend to pump rainwater to flush toilets and so on, then a pump and irrigation filter would be required.

Installation would be extra, and this depends on the distance to the house fixtures and the degree of difficulty in supplying water to the house.

Adding options such as a leaf eater, first-flush device, overflow to gardens and a filter bag is highly recommended.

» DID YOU KNOW?

If each household installed a rainwater tank, reused its graywater, modified the garden, installed water-efficient fittings and appliances, and minimized water wastage, then we could reduce domestic water consumption by 50%.

Installing a graywater system or rainwater tank is commendable but when you integrate these types of strategies as part of a water management plan, then real differences in water consumption and use can be observed.

Imagine harvesting rainwater, using it to wash clothes, and then collecting the graywater to use on the garden. In many households 50–60% of municipal supplied water is used inside the house and the balance outside in garden areas.

Laundry use can be anywhere from 14–18% and toilet flushing 12–15% of the total daily use, so that totals just over a quarter of our internal household use. Bathroom use is even greater at about 18–20%.

Now if we can use rainwater to completely supply laundry and toilet flushing, and then capture all of the laundry and bathroom water by a gray-water device to water the garden, then we have reduced our town water use significantly.

If we can reduce town water supply by 25% and then capture 33% of our household use to offset what we use in the garden, then we greatly reduce our overall consumption. We can then further reduce our outside water use by installing dripline or some other water-efficient watering equipment.

This holistic approach of an integrated water system is the concept behind town water neutral gardening, as advocated by Josh Byrne. Through design and the use of water-efficient devices and techniques, appropriate fit-for-purpose water sources can be better utilized. For example, it seems absurd that we use disinfected class A water (drinking water) to flush a toilet, and if shallow well water is available then it can supplement graywater use in the gardens when the family is on holidays or at other times.

We need to promote improved water management through behavioral change, and this then leads to reduced water consumption. Rural families that solely use rainwater for their water supply generally use 15% less water than their urban counterparts.

People are misguided if they think that technology will overcome future water and resource shortages, so getting people to change what they do and how they think is the battle we face.

Wastewater is really wasted water. It is a resource we cannot afford to literally throw away. There are three main ways in which our daily household waste-water is treated. Many urbanized and modern cities have a reticulated sewer system, whereby household wastewater is piped to a central treatment plant and then pumped to discharge — either to the ocean or on land.

This is an expensive way to treat wastes, simply because of the huge investment in infrastructure, operation and maintenance that is undertaken for these large-scale projects.

» DID YOU KNOW?

The aim of sewage treatment is to remove or reduce the following pollutants:

• organic matter (monitored as BOD — Biochemical Oxygen Demand)

• suspended solids

• nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, too much of which negatively impact on our waterways

• pathogens (organisms that cause disease).

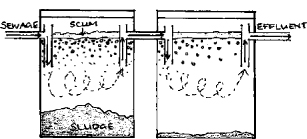

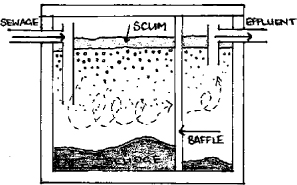

If household wastewater is not piped off the property then some type of on-site treatment plant is required. The first, and cheapest, option is the septic tank. This can be two tanks (or one tank with a baffle to separate two chambers or compartments) that are essentially an anaerobic digestion system (hence the term “septic”).

The first tank or chamber is the primary sedimentation tank. It holds all of the solids from the household, and much of this is broken down by bacteria and other microorganisms. Treated effluent is drawn from the middle of the first tank and enters the second tank where further digestion of the waste occurs.

Double septic tank system

Septic tanks are designed to hold all of the daily waste for a few days to enable break down and separation. The retention time that waste is held is crucial to the success of waste digestion, and if too much waste-water enters the system then the bacteria don’t have enough time to break it all down.

A single septic tank may have a baffle to separate chambers.

Partially treated effluent is then passed into some type of soil absorption system. This may be leach drains, stone-filled beds or trenches, or soak wells. The size of the leach field is proportional to the daily volume of wastewater and inversely proportional to the porosity of the soil. For example, if the soil is clayey in nature and water only percolates slowly into it, then the drains need to be larger or longer.

All wastewater treatment systems require maintenance. Unfortunately, most people ignore the septic tank until it floods or starts to smell or the toilets back up and a plumber is called. Once the tanks and drains are buried most people have an “out of sight, out of mind” attitude.

In non-sewered areas, septic tank systems are still the norm. However, sometimes the soil is not suitable for continuous discharge and there may be sensitive waterways nearby or a high water table. As more councils require stringent effluent discharge quality, the installation of secondary treatment systems is steadily increasing. These whole-of-house systems treat all waste-water to a much higher standard and the discharge water can then be used to irrigate gardens.

An alternating leach field

An Aerobic Wastewater Treatment System (AWTS) is also called an Aerobic Treatment Unit (ATU) and they provide both primary and secondary treatment of domestic wastewater. Typically, they consist of several chambers (or even separate tanks) where some combination of biological, physical and chemical processes is employed to remove the pollutants.

The first chamber is the primary sedimentation chamber and it operates in a similar manner to a septic tank. Anaerobic bacteria digest much of the wastes and produce various gases such as carbon dioxide, methane and nitrogen, which are vented.

The second stage is the aeration stage. A blower pumps air, either continuously or on a cycle, through a diffuser, which forces air bubbles into and throughout the wastewater effluent. Different types of bacteria exist when air is plentiful and the chemical processes that occur are different also.

A cross-section of an AWTS

Once all of the effluent has been stirred up it needs time to allow the floc (minute undigested or insoluble particles) to settle to the bottom of the clarification chamber as sludge.

Every septic tank and AWTS will accumulate scum (floating on top) and sludge (muck that sinks to the bottom). This is because the bacteria that digest human wastes are not that good at breaking down oil and fats (scum) and some solids (and this includes toothpicks, cigarette butts, plastic, condoms, cotton buds and lumps of toothpaste, which unfortunately end up in the system).

Much of the sludge is also dead bacteria. Eventually every tank needs to be pumped out and desludged, most often between 3–10 years, depending on the system and what enters the system.

Some of the sludge in the clarification chamber is returned, often by an air-driven lift pump, back to the primary chamber. Monitoring the volume of sludge in the aerated mix is also a good indication of when the tanks need pumping out by a liquid waste contractor.

The clear, settled liquid is then passed through some type of disinfection process, using chlorine tablets, UV light or ozone, and then into the pump chamber. As the treated water rises in this chamber, the float switch activates and water is pumped to the irrigation area.

All of these very complex processes are designed to treat sewage to a level suitable for surface irrigation. This includes dripline or special sprinklers, which only permit a short width and height spray so that the treated effluent is not showered on buildings, paths, animals and people.

Every state, province or country has rules and regulations about how much irrigation is required, plume (spray) height and the setback distances from buildings and boundaries.

Aerated treatment systems are biological systems and require servicing and maintenance by experienced, registered service technicians. They are more expensive than septic tank systems to install and maintain.

Furthermore, pumps and blowers use electricity and occasionally need replacement. All of this adds ongoing costs to the overall operation of the system, but about 50,000 gal each year can be used to irrigate lawns and gardens.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Most municipal wastewater treatment plants are designed for tertiary treatment. This is a further stage of wastewater processing before any effluent is released to the receiving environment. Here, more nutrients are removed (so less nitrogen and phosphorus), greater filtration and settling may occur to produce higher-quality effluent and greater levels of disinfection ensure complete pathogen kill.

Besides capturing, using, treating and recycling water, we need to keep water in the soil. This is particularly important on rural properties (see next chapter), but is easily applied in small urban properties too.

The first step is to capture runoff, and then we choose to hold water there or move it through the landscape and direct it to dams and storage. Basically, we need to slow it, spread it or sink it. How soil can be improved to hold more water was discussed in chapter 4 and moving water through drains and into dams is discussed in chapter 11.

On an urban block you could easily divert stormwater from a downpipe into a garden bed, an orchard area or a small basin.

You can create mini compensation basins or sumps in garden areas. These can receive the runoff from hard surfaces (paths, driveway and roof) and soak away over time. These shallow sumps become landscape features in the garden and are an alternative to the more traditional underground storage tanks.

You can divert stormwater off a path into the garden.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Water has remarkable properties. When it freezes it expands, becomes less dense and this is why it floats.

Freezing water inside plant tissues can have devastating effects. Some plants that live in very cold climates have special features to prevent damage to their cells.

Certain plants seem to be able to change the structure of their cell membranes and as water freezes it can expand through the membrane into other spaces.

Other plants convert starch into sugars and this changes the composition of the liquid inside the cells. Essentially the sugars act like antifreeze and the plant withstands very cold temperatures without the cell liquid actually freezing. While the fluid inside the cell doesn’t freeze, any water between cells can freeze and expand, but this doesn’t cause much damage and the plant can recover.

Finally, a few plants can allow the cellular liquid to become viscous (thick), almost becoming solid, and this also helps plants to withstand very low temperatures.