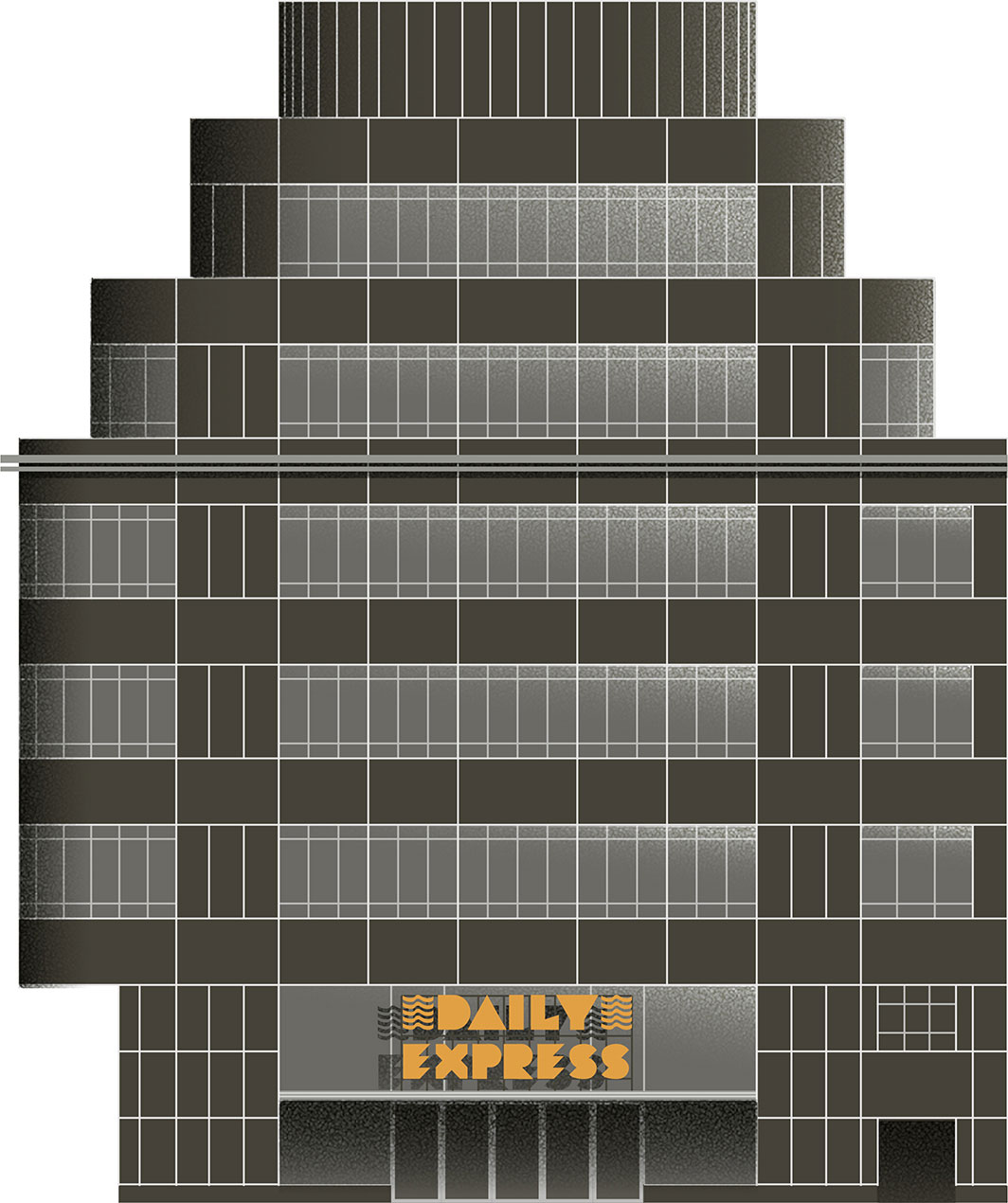

It is 1929 and the Wall Street Crash has triggered global economic collapse. Britain, strongly tied into the global economy and still weakened by the First World War, is taking a direct hit. Factories and businesses are closing, leaving millions without income. In Glasgow, only 50% of people still have a job. But London, again, appears unfazed by the economic slump. While the rest of Britain suffers mass unemployment as many ‘old’ industries – such as coal mining and shipbuilding – decline, London is becoming a home for all sorts of new businesses. Demand for cars, electrical appliances and other ‘London-made’ products is rising amid the crisis, ensuring the city’s wheels remain firmly in motion.

One of the most popular of these new electrical appliances was the radio, known as the ‘wireless’ at the time. On its arrival in Britain, a decision was made not to repeat the chaotic expansion of commercial radio stations seen in the US.

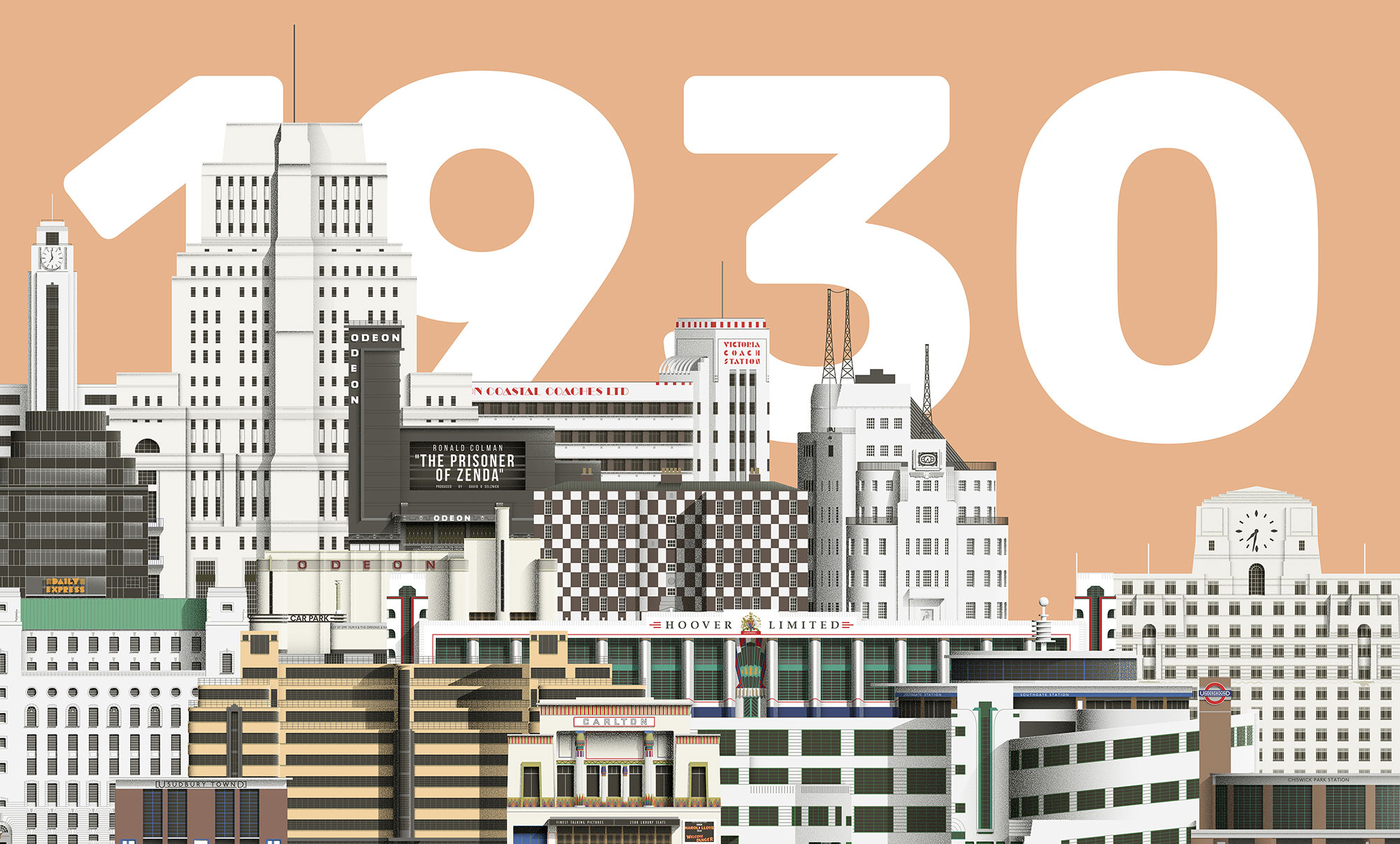

A single licence was issued to the British Broadcasting Corporation, which soon expanded and established studios all around town. Broadcasting House (011) was designed to put everyone under one roof. The building had to adapt to an odd-shaped site, and what’s more, there were height restrictions due to the ‘ancient lights’ of neighbouring houses.

011 Broadcasting House

George Val Myer & Raymond McGrath

1932

1932  W1A 1AA

W1A 1AA

Ancient ‘right to light’ legislation protected buildings receiving natural daylight; those that had received unobstructed natural light for more than twenty years could prevent any construction that would block it. This meant that the eastern front had to be redesigned. The building is consequently asymmetrical, sloping on one side with a long mansard roof reaching to the fourth floor. Special attention was given to the construction of soundproof recording studios. They were placed inside a huge brick tower, which was built inside the steel-framed building. More than 2.6 million extra-strong bricks made the walls 1.4 metres thick at the base.

Morris Royal Air Mail Service Car

This odd-looking car was a one-off, built to promote the newly launched Royal Air Mail Service from Croydon Airport in 1934. The streamlined, aircraft-inspired design turned heads, and the car appeared in commercials and on stamps as far away as New Zealand.

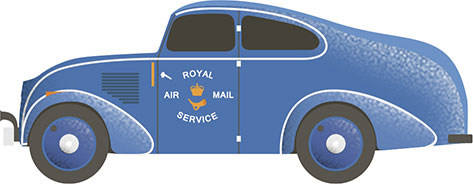

The traditional printed media were also demonstrating a progressive architectural style at the time. The Daily Express Building (012) – on Fleet Street (where else?) – did its bit in attracting attention. A streamlined façade by Ellis and Clark features rounded corners covered in shiny black glass. One of the first uses of curtain façades in Britain made the surrounding buildings look archaic.

012 Daily Express Building

Ellis and Clarke with Owen Williams

1932

1932  EC4A 2BE

EC4A 2BE

During the construction, a banner proudly announced: ‘Britain’s most modern building for Britain’s most modern newspaper’. It was such a success that the Daily Express built its next two branches in Manchester and Glasgow using the same black glass façades.

Handley Page H.P.42

The huge airliner had luxurious cabins modelled on the cars of the Orient Express, which included a cocktail bar. It was a remarkably safe but awfully slow aircraft, with a cruising speed of only 90mph. It operated from Croydon Airport, the largest airport in the UK at the time.

The 1930s saw the golden age of cinemas. The era of silent films was slowly coming to an end, but the Carlton Cinema (013) in Islington still opened screenings with a large organ – used to provide both soundtrack and sound effects for silent films. The organ was used frequently, as the cinema staged shows with comedians, dancers and singers between Hollywood blockbusters. Alongside four changing rooms, there were almost 2,300 seats and a café. The exterior is covered in multi-coloured tiles and decorated in Egyptian patterns. It was designed by London-born George Coles, an expert in cinema architecture.

013 Carlton Cinema

George Coles

1930

1930  N1 2TS

N1 2TS

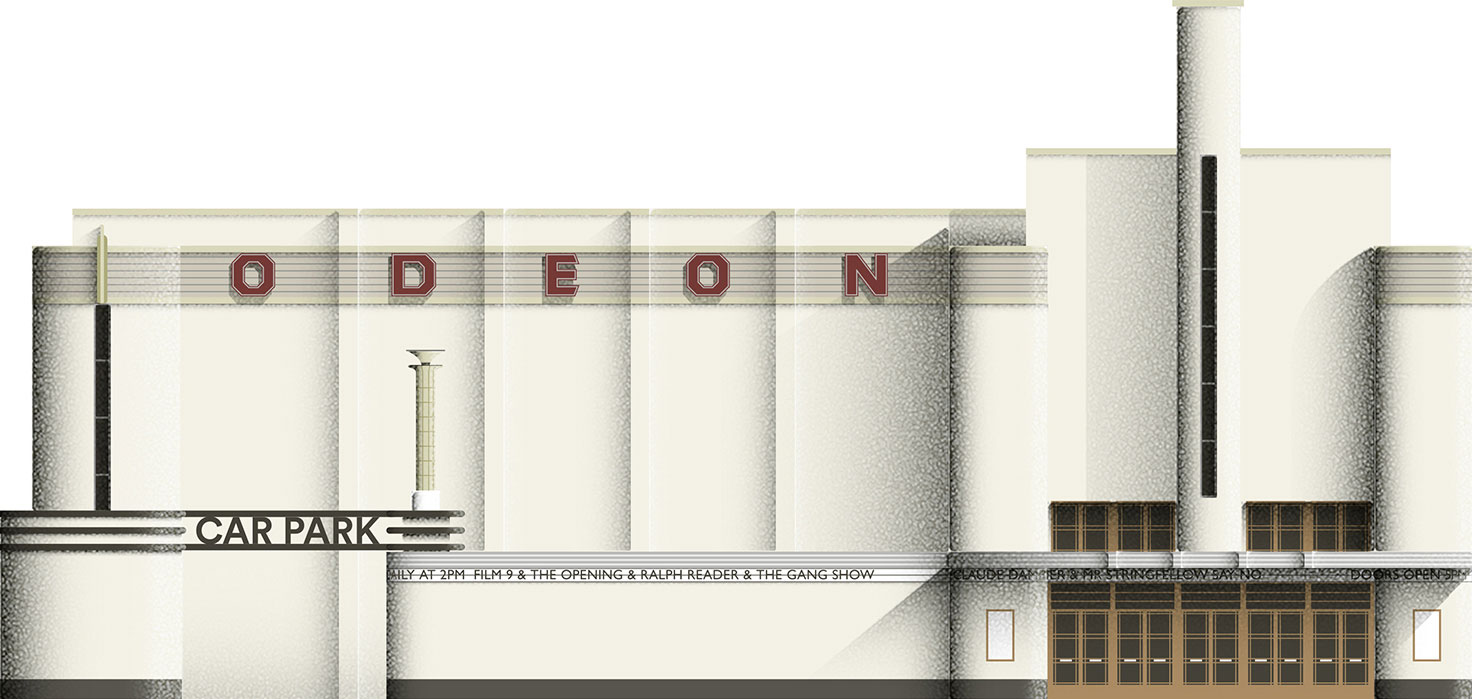

The cinema chain Odeon was established in 1931. Its founder, Oscar Deutsch – from Birmingham – was famous for his extreme working hours and endless energy. In just ten years, he commissioned well over a hundred brand new cinemas around Britain. These new buildings were often the first examples of contemporary architecture ever seen by ordinarily sleepy British towns. Deutsch died prematurely, aged just forty-eight, but still managed to change the look of the British Isles forever. The chain’s name comes from ancient Greece and was popular for cinemas in Italy and France, but Deutsch and his publicity team came up with the clever ‘Oscar Deutsch Entertains Our Nation’.

Coles became one of Deutsch’s favourite architects and helped to develop the ‘Odeon Style’. An example of this style is Woolwich Odeon (014), built in 1937. Free of decoration, its streamlined curved façade is covered in glossy cream tiles. The exterior is reminiscent of modernist European architecture, while the interior has a touch of American Art Deco. At night, the whole building would dazzle passers-by with floodlights – a clear bid at detracting attention from the Granada Woolwich, which stood just across the road. The Granada cinema had opened only six months earlier and offered 300 more seats, although its brick façade was definitively less impressive.

014 Woolwich Odeon

George Coles

1937

1937  SE18 6QJ

SE18 6QJ

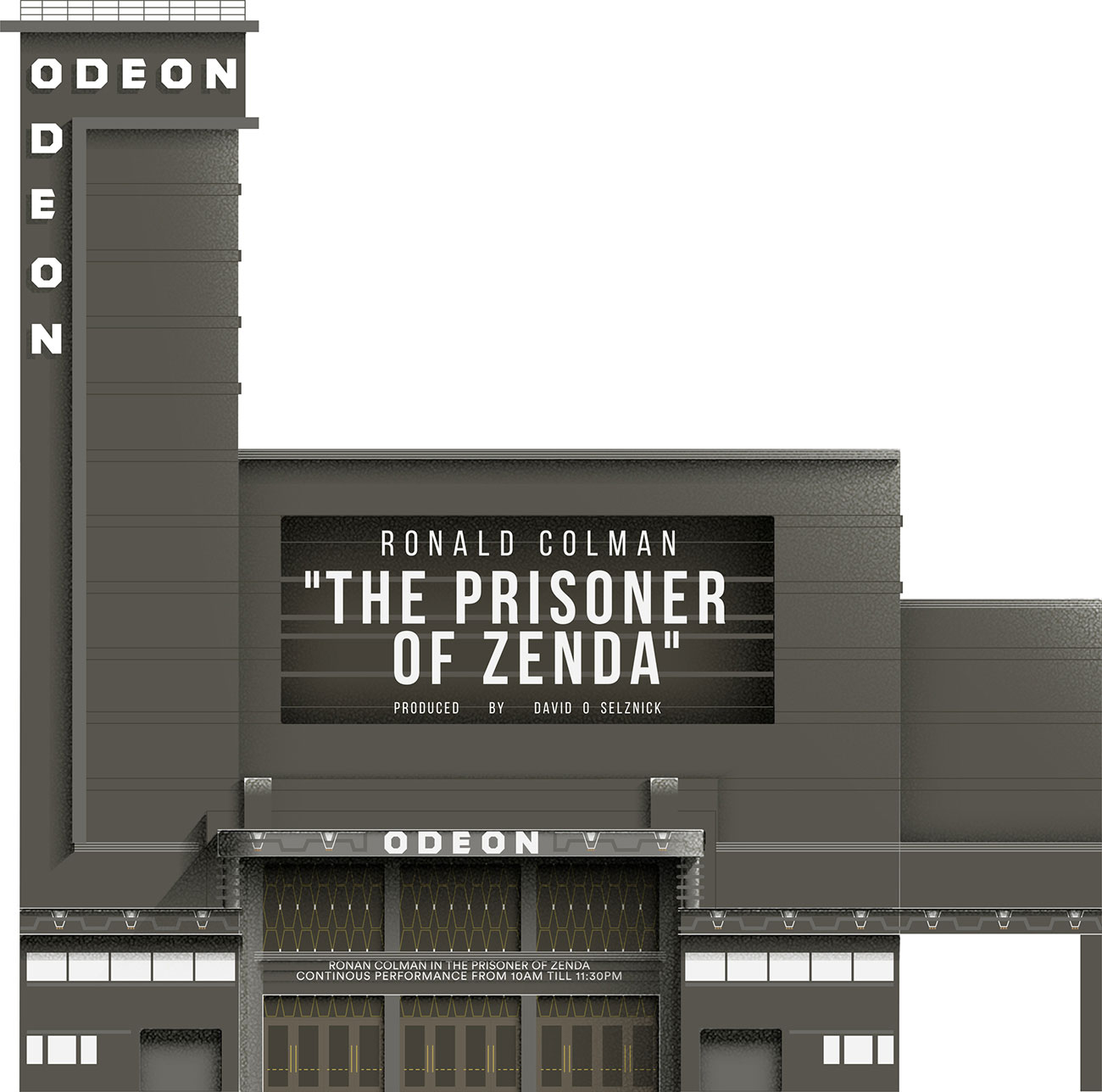

Only a month after the Woolwich branch launch, a flagship Odeon cinema opened. The Leicester Square Odeon (015) was designed by an ex-fighter pilot from Birmingham called Harry Weedon, alongside Scotsman Andrew Mather. It looked like no other cinema. The façade, made from polished granite, is a striking black. The huge mass of the building is crowned by a thirty-seven-metre-high tower with the Odeon lettering blazing in neon.

015 Leicester Square Odeon

Harry Weedon & Andrew Mather

1937

1937  WC2H 7JY

WC2H 7JY

It was, and still is, the largest single screen cinema in Britain. The building cost per seat was four times higher than the other major Odeons built at the time. The Leicester Square branch still hosts many major film premieres in Britain, some eighty years later. But most of its contemporaries weren’t that lucky. When television invaded British living rooms, cinema audiences sharply declined. Many cinema buildings were closed down or turned into bingo halls. The Carlton in Islington found secondary use as a church.

The automobile industry was another that experienced a huge boost in the 1930s. The driving licence became a legal requirement only in 1934. Before that, anyone over the age of seventeen could drive, with no tests or training needed. As there were very few road rules, more than 1,000 Londoners died on the roads every year, most of them pedestrians and cyclists. The Minister of Transport, Leslie Hore-Belisha, tried to fix that. ‘Belisha Beacons’ – a black and white pole with a yellow globe on top – were installed at pedestrian crossings around the city and they remain to this day.

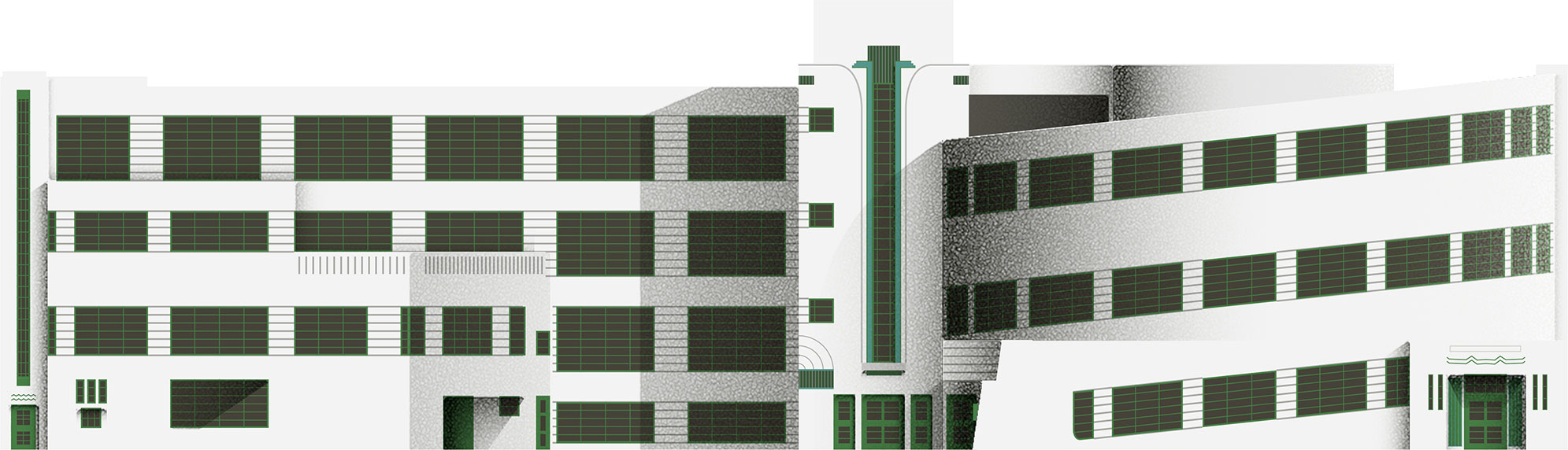

A number of well-off Londoners preferred not to own a car, let alone drive one. Instead, they hired limousines with chauffeurs from places such as the Daimler Hire Garage (016). The three-storey building incorporated a huge spiral ramp leading to the top floors, one of the first in the UK to have this feature. Designed by Wallis, Gilbert and Partners, it was opened in 1931. The top floors were used for Daimler cars, while the basement was for privately owned vehicles. The building contained Daimler offices, a petrol station and facilities for chauffeurs. The company was later swallowed by the American Hertz car rental firm. Later, the building served as a garage for taxis and coaches and it is now home to an international advertising agency.

016 Daimler Hire Garage

Wallis, Gilbert and Partners

1931

1931  WC1N 1EX

WC1N 1EX

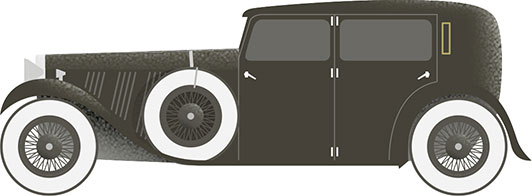

Daimler Double Six

Daimler limousines were a favourite of the European rich and famous. The oldest British car maker even provided official transport for the royal family until 1950.

Austin Seven Tourer

At the price of £125, this was one of the first cars that a middle-class British family could afford. People soon nicknamed it a ‘bath on wheels’ due to its small stature.

Wallis, Gilbert and Partners was a partnership between English architect Thomas Wallis and American construction firm Trussed Concrete Steel, which pioneered in reinforced concrete factories in Detroit. Interestingly, it is believed there was in fact no ‘Gilbert’ at the firm, the name being included simply to make the practice appear larger. After the success of his Firestone Factory (002), Wallis went on to design a number of factories for overseas companies such as Gillette (shaving products), Wrigley’s (chewing gum) and Hoover (vacuum cleaners). Wallis’ buildings are now regarded as some of the finest examples of 1930s architecture in Britain. But when they opened, the reviews were mostly on the opposite spectrum. It’s fair to say that Wallis disliked architecture critics as much as they disliked his buildings. After reading one of the negative reviews, he reportedly visited the editor of Architectural Review with a horse whip.

His next building in London, using the same reinforced concrete system, was Victoria Coach Station (017), which is located conveniently near Victoria Train Station. A huge five-storey frontage contained a booking hall, shops, buffet, lounge bar, 200-seat restaurant and offices. On completion in 1932, Wallis, Gilbert and Partners became the first occupants. Behind the building is a station yard, with enough space for seventy-six buses. Much of the traffic of the time was recreational coastal coaches that took Londoners to beaches in Sussex and Kent.

017 Victoria Coach Station

Wallis, Gilbert and Partners

1932

1932  SW1W 9TP

SW1W 9TP

de Havilland Express

At the time, this was the fastest British-built passenger aircraft. Operating from Croydon Airport, it was run by the Railway Air Services – an airline oddly operated by four rail companies.

Belisha Beacon

First introduced in 1934, the idea spread as far as New Zealand.

The most famous (and most decorative) building of Wallis, Gilbert and Partners is without a doubt Hoover Building (018). Built for the Ohio-based manufacturer of vacuum cleaners, it was a factory supplying the growing British market. Sitting on Great Western Road alongside a stretch of factories built during this period, it was floodlit at night. The front was faced with snowcrete – a special whitened concrete – and decorated with coloured tiles. The entrance is especially elaborate. Wallis, never bothered with aligning to any existing norms, called his architecture style simply ‘fancy’.

018 Hoover Building

Wallis, Gilbert and Partners

1933

1933  UB6 8AT

UB6 8AT

Cocky door-to-door salesmen and constant advertising boosted sales and the factory had to expand only two years after opening. During the Second World War, it was repurposed to produce electronic parts for tanks and aircraft. To hide it from German bombers, it was repainted and covered in camouflaged netting. When the factory closed in 1982, Tesco bought the site and turned it into a large supermarket. As of 2018 it remains, although now in the form of snazzy flats.

Kiosk No 6

The Telephone Box was designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, the architect of the Battersea Power Station (039). Many remain on London streets to this day, although they are now predominantly used as a background for tourist selfies.

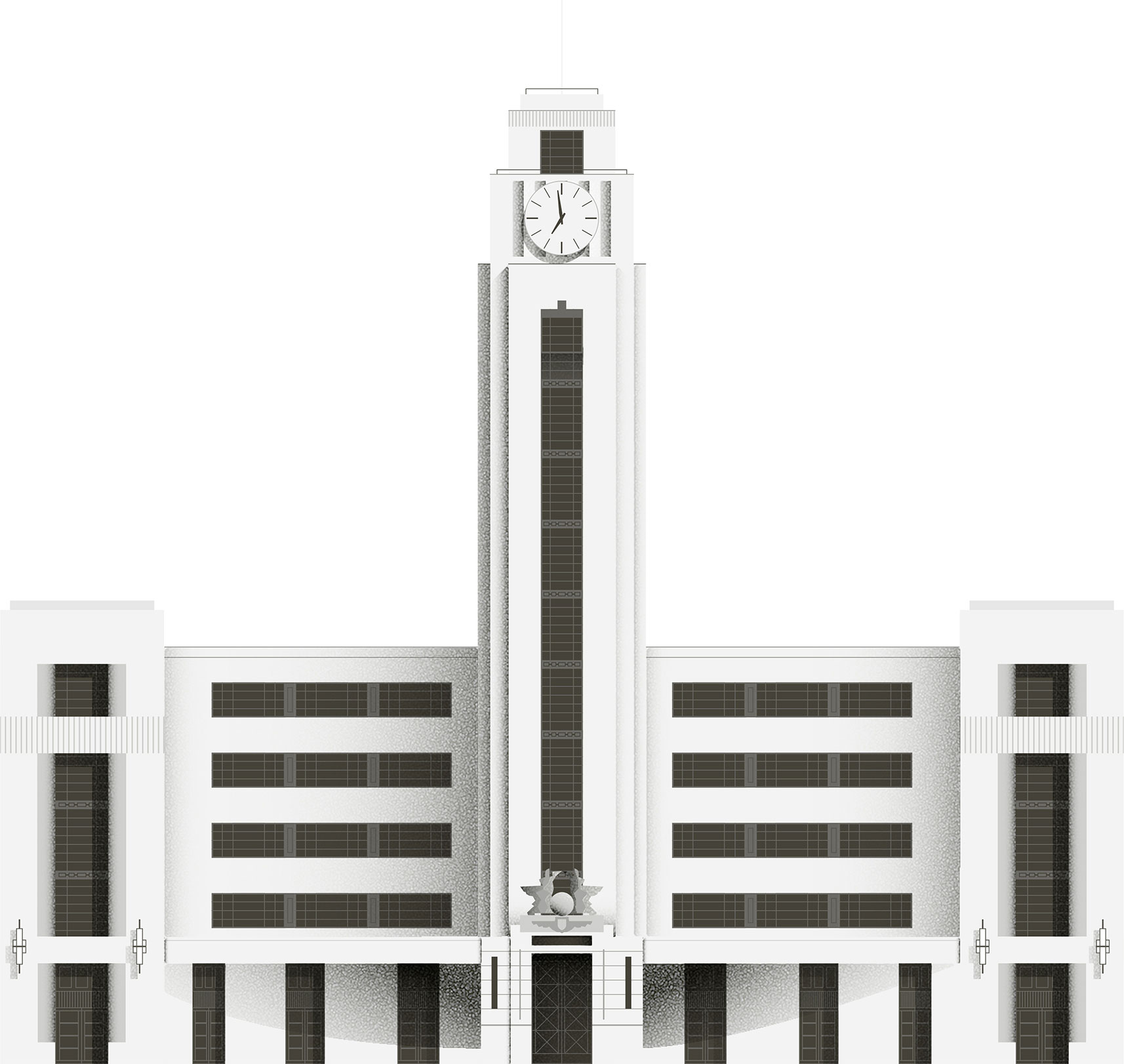

Air travel was instrumental to London’s new global status. Imperial Airways, Britain’s largest airline, expanded their operations from Croydon Airport to a flying boat terminal in Southampton. As the number of passengers rose, the company decided to build an Imperial Airways Terminal (019) in Victoria. The symmetrical building has a ten-storey clock tower, flanked by five-storey wings.

019 Imperial Airways Terminal

Albert Lakeman

1939

1939  SW1W 9SP

SW1W 9SP  43M

43M

Clad in Portland stone and with a minimalist approach, it looks almost austere from the outside. Amazing Art Deco interiors provided travellers with all the luxury they could desire. In contrast, the back of the building, not visible from the street, was left in brick – probably in an effort to save money. The terminal was built far from any airport, but right by Victoria’s Train and Coach Stations. It had direct access to a platform for special first-class trains destined for Southampton.

The Underground continued its successful expansion at an even faster pace than before. In just one decade, twenty new stations opened and numerous existing stations were rebuilt. In 1930, the head of the Underground Frank Pick, together with his favourite architect Charles Holden, travelled to the continent to check out the latest architectural trends. They visited Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden – admiring in particular the architecture style known as the ‘Amsterdam School’. Holden developed a new look for the Underground, which wasn’t an imitation of continental architecture, but an adaptation for local materials and use. He called the new stations simply a ‘brick box with a concrete lid’. They became an inspiration for a number of new schools, hospitals and power stations around the UK.

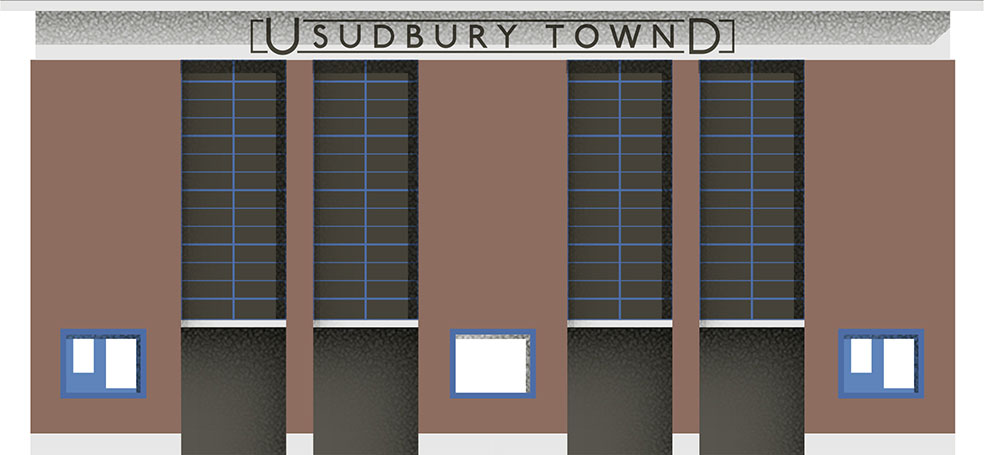

The first prototype of the new style for the Underground was Sudbury Town Station (020) on the Piccadilly Line. A double-height ‘brick box’ with large panels of glazing is covered with a ‘concrete lid’, which overhangs the sides. Unusually, the station’s sign on the façade comprised neon tubes that illuminated the station at night. This was the only use of neon in any London station, but it was too expensive to maintain and the sign was taken down in the 1950s.

020 Sudbury Town Station

Charles Holden

1931

1931  HA0 2LA

HA0 2LA

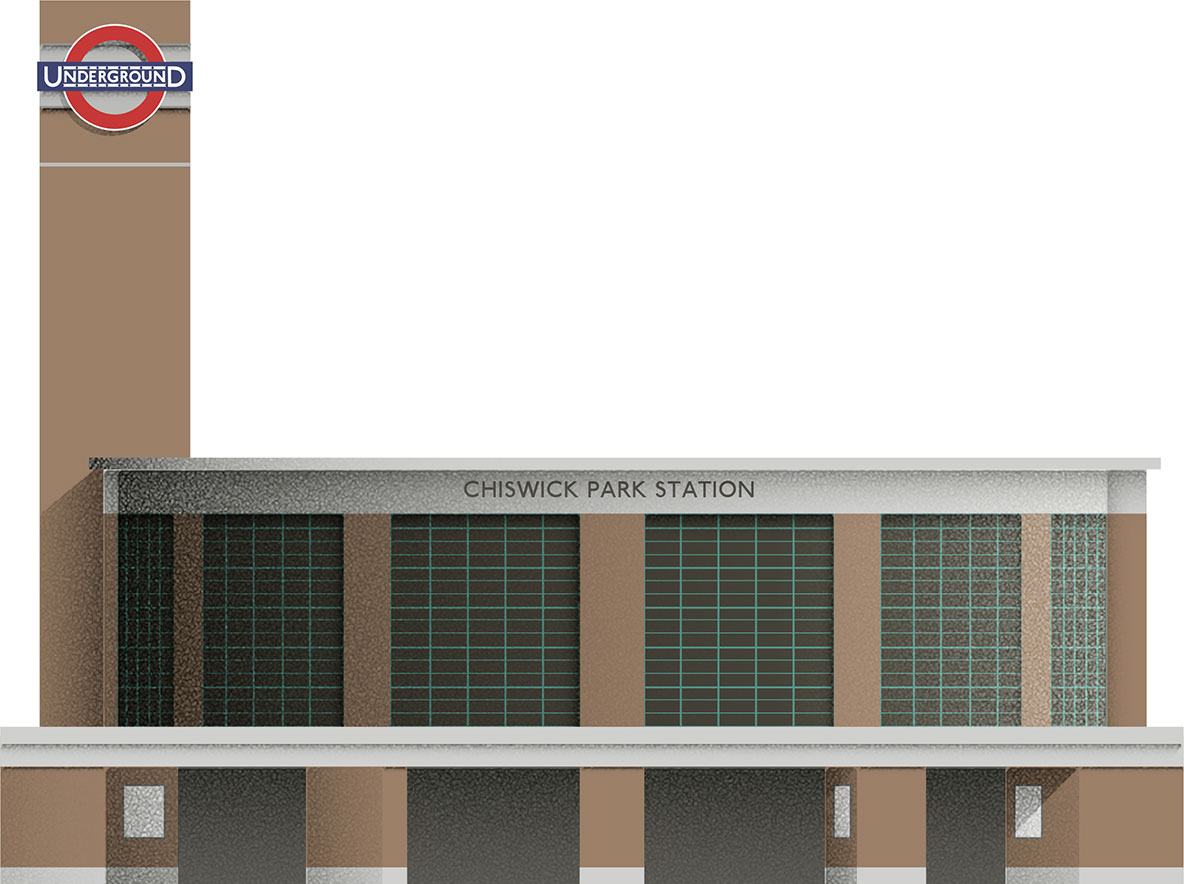

Chiswick Park Station (021) on the District Line opened a year later. The station sits on an odd corner site, between curving railway tracks and randomly scattered suburban roads. The concept follows the ‘brick box with a concrete lid’ rule, although the ‘box’ is drum shaped this time. A sturdy brick tower, whose only purpose is to show off the roundel in the distance, is attached from the west.

021 Chiswick Park Station

Charles Holden

1932

1932  W4 5NE

W4 5NE

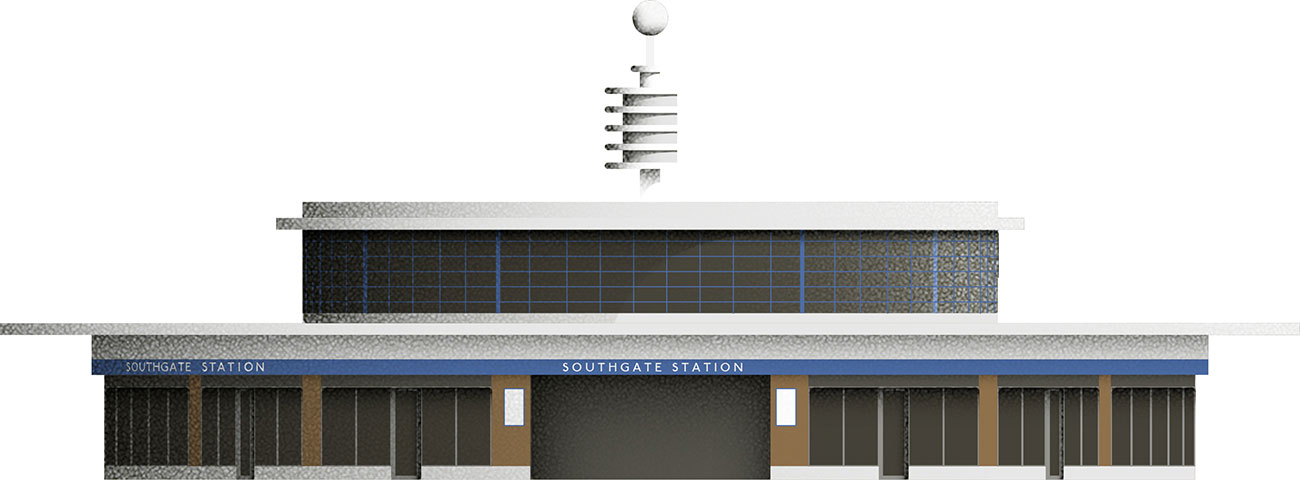

However, the most playful of all the 1930s stations is undoubtedly Southgate Station (022). It’s a circular drum with a high central booking hall surrounded by lower offices and shops. The booking hall’s ceiling seems to be levitating, supported only by a single pillar in the centre. The cherry on the top is a lighting beacon on the roof, visually inspired by a Tesla coil. Decades later, the beacon became an inspiration for the Daleks in the Doctor Who television series.

022 Southgate Station

Charles Holden

1933

1933  N14 5BH

N14 5BH

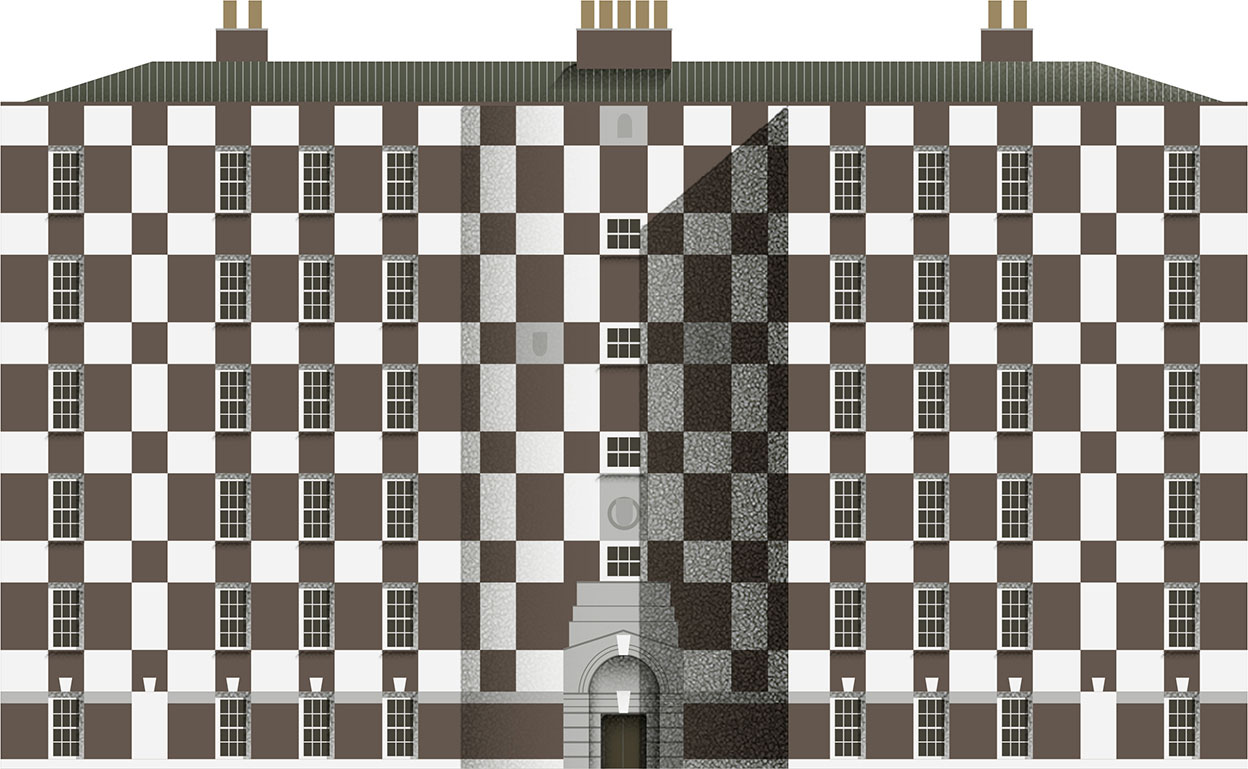

While the middle class fled to the suburbs with the help of the Underground network, the less wealthy were confined to their old crowded neighbourhoods. The Duke of Westminster donated land to the Westminster City Council for a new social housing project, although under one condition – it had to be designed by Edwin Lutyens, a famous architect known for his palaces in New Delhi and other grand projects. With Page Street Estate (023), Lutyens proved he could operate under a more modest budget. The chequered buildings have one of the earliest examples of gallery access, which helps to increase the floor area of each unit. But what proved most controversial was that every flat had its own toilet. While this was quite common for the middle class, it was not at all usual for working-class tenants. For them, the norm was to use shared outdoor lavatories.

023 Page Street Estate

Edwin Lutyens

1930

1930  SW1P 4EN

SW1P 4EN

A1-Class ‘Diddler’ Trolleybus

At its peak, London had the largest network of trolleybuses in the world. They were much quicker than the trams and buses, and were well liked by passengers.

Somewhat surprisingly in light of the Wall Street Crash, the City saw significant growth during this period. Banks and insurance companies built impressive new offices, and the workforce rose by more than 40% between 1911 and 1938. This placed significant pressure on authorities to review existing building restrictions, and in 1930 a new London Building Act was approved. The maximum height allowance increased from twenty-four metres to thirty metres, but even that wasn’t enough. The London County Council started issuing waivers permitting certain buildings to break the limit.

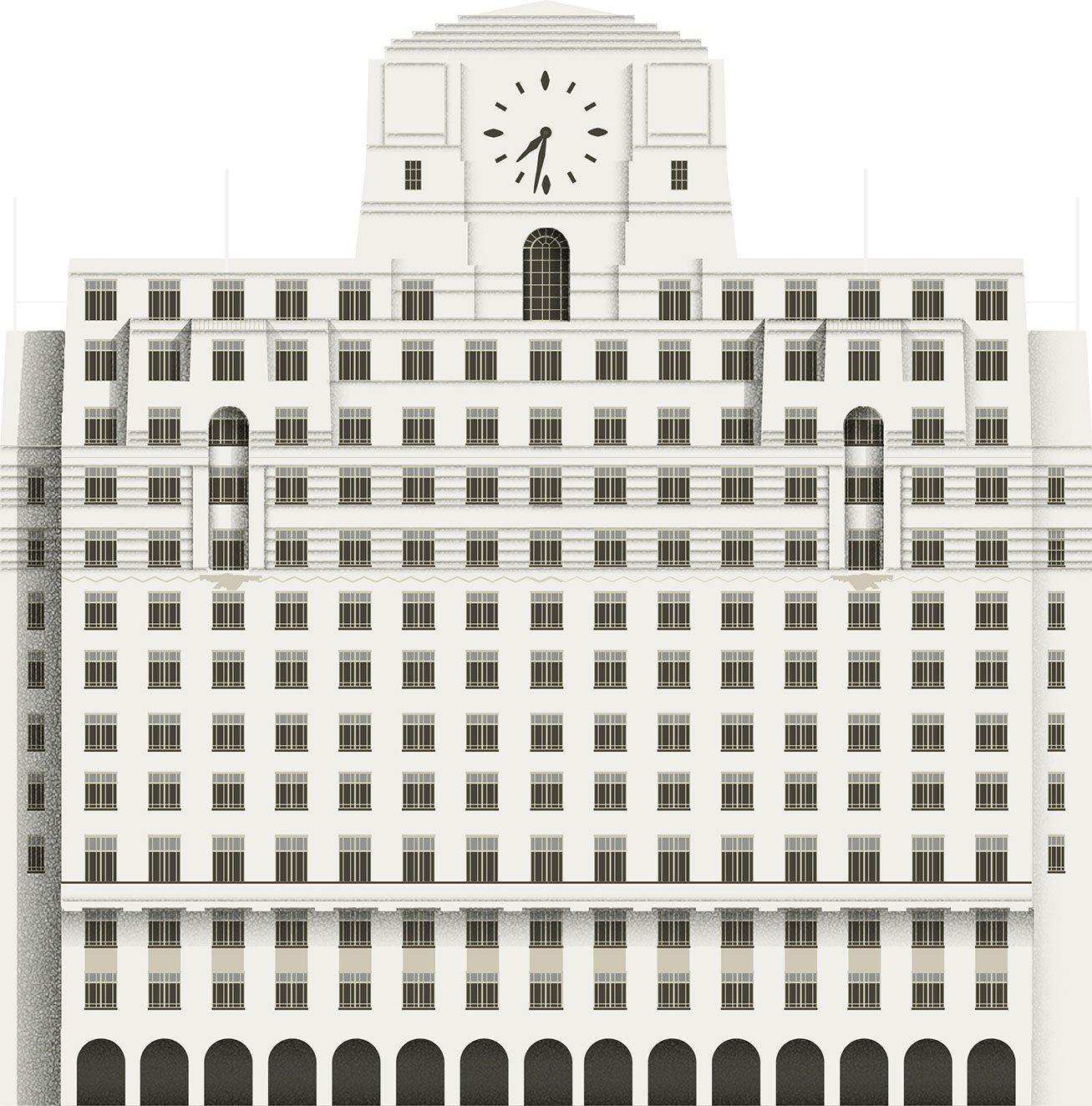

Charming Shell Mex House (024) on the Strand, built just a year after the new legislation came in, was way over the new height limit. Its carcass was the Cecil Hotel, which was the largest hotel in Europe with 800 beds. This heavily decorated building was stripped to the bone, reinforced and rebuilt in the Art Deco style. On top of the huge mass of twelve floors sits the largest clock face in the UK. Contemporary Londoners nicknamed it ‘Big Benzene’. The clock helped Shell Mex House to beat 55 Broadway (008) in height by five metres.

024 Shell Mex House

Ernest Joseph

1931

1931  WC2R 0HS

WC2R 0HS  58M

58M

Cierva C.30

The work of Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva, the Cierva was a step between an airplane and a helicopter. The Metropolitan Police were very interested in the idea, and trialled the Cierva for surveillance and traffic spotting during the 1930s.

The spectacular Ibex House (025) was a speculative development, which offered rental space with all possible services provided. When it opened in 1937, it claimed to be ‘the most up-to-date block of City offices’. This was certainly true style-wise, as it embraced a cutting-edge modernism from continental Europe – something unseen in the still very conservative City.

025 Ibex House

Fuller, Hall and Foulsham

1937

1937  EC3N 1DY

EC3N 1DY

The enormous eleven–storey building is softened with round corners, beige tiles and receding top floors. Its H-plan allows for light to enter every room. Horizontal window bands – the longest strip windows in London – curve around the whole block, reminding one of the work of Erich Mendelsohn, a leading modernist architect who had fled Nazi Germany for Britain a couple of years earlier.

London saw an influx of refugees from Nazi Germany and Central Europe during this period, as tensions on the continent continued to mount. Immigrants included not only Jews, but also influential modern artists and architects whose work the Nazis saw as ‘degenerate’. Some of them continued on to the US, while others made Britain their home. Their enriching influence on architecture in both countries is undeniable.

As office space around the capital grew and telephones became more affordable, the number of phone calls increased rapidly. Back then, every call went through a switch station, where operators had to physically connect the right cables for the call to be put through. But a new dial telephone (cutting-edge technology at the time) skipped the human operators and the call was connected by automatic relays.

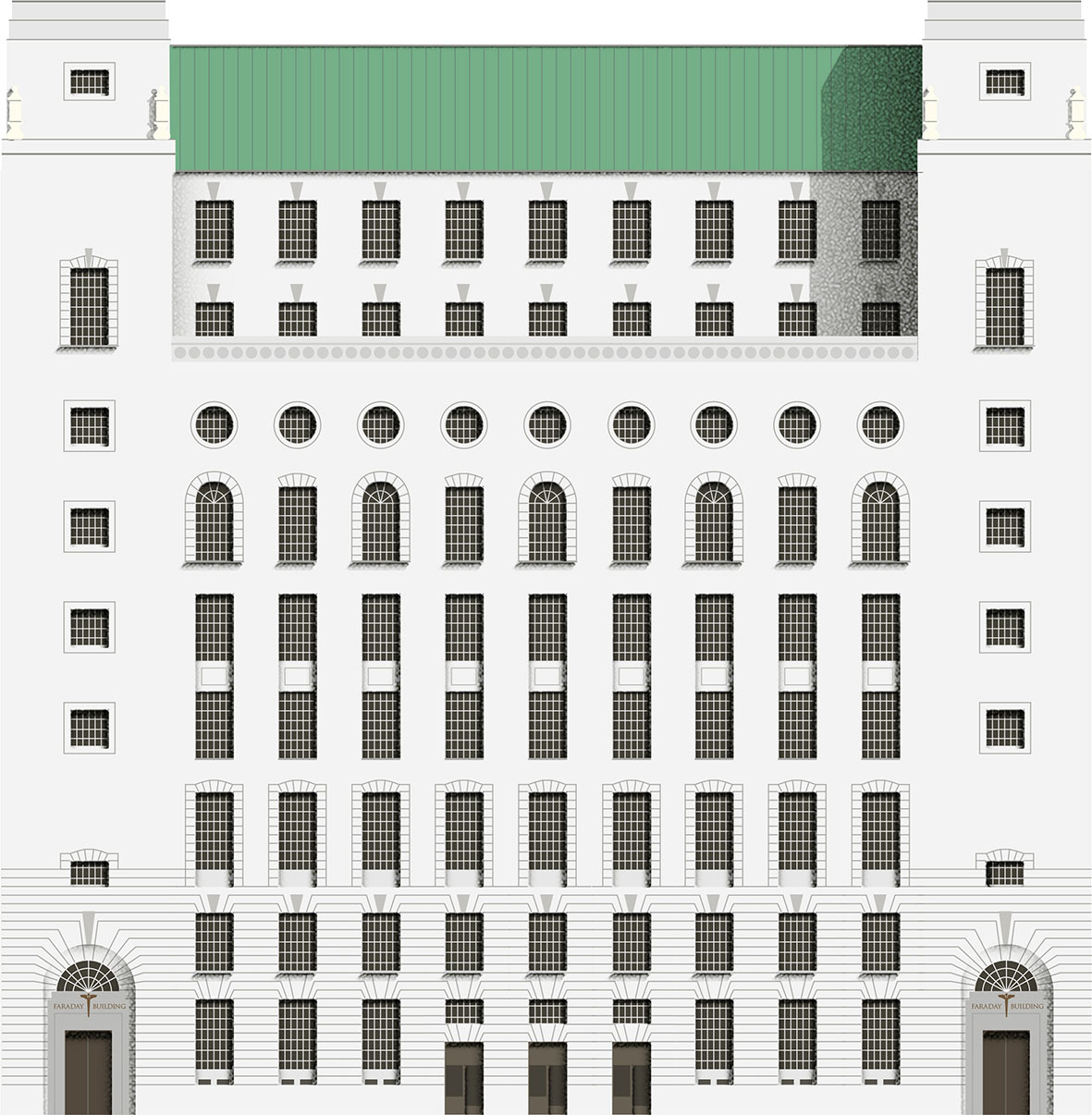

The Faraday Building (026) was built to speed up the calls and to connect London with the outside world. It had 6,000 lines in an automatic exchange and all international telephone calls were routed through it (apart from those to Japan, China and Albania). The façade is neoclassical, but has a great twist – the keystones (the triangular stones crowning the windows and doors) have engraved motifs related to telecommunication, such as telephones and undersea cables.

026 Faraday Building

A.R. Myers

1933

1933  EC4V 4BY

EC4V 4BY  47M

47M

On completion, the height of the building caused outrage. Although it was nowhere near the tallest building in London, it blocked the view of St Paul’s Cathedral from the River Thames. This led to a new law that protected sight-lines to the cathedral and restricted the height of buildings in its vicinity. This law is still in operation, and the Faraday Building remains the tallest between the cathedral and the river (and still obstructs the view).

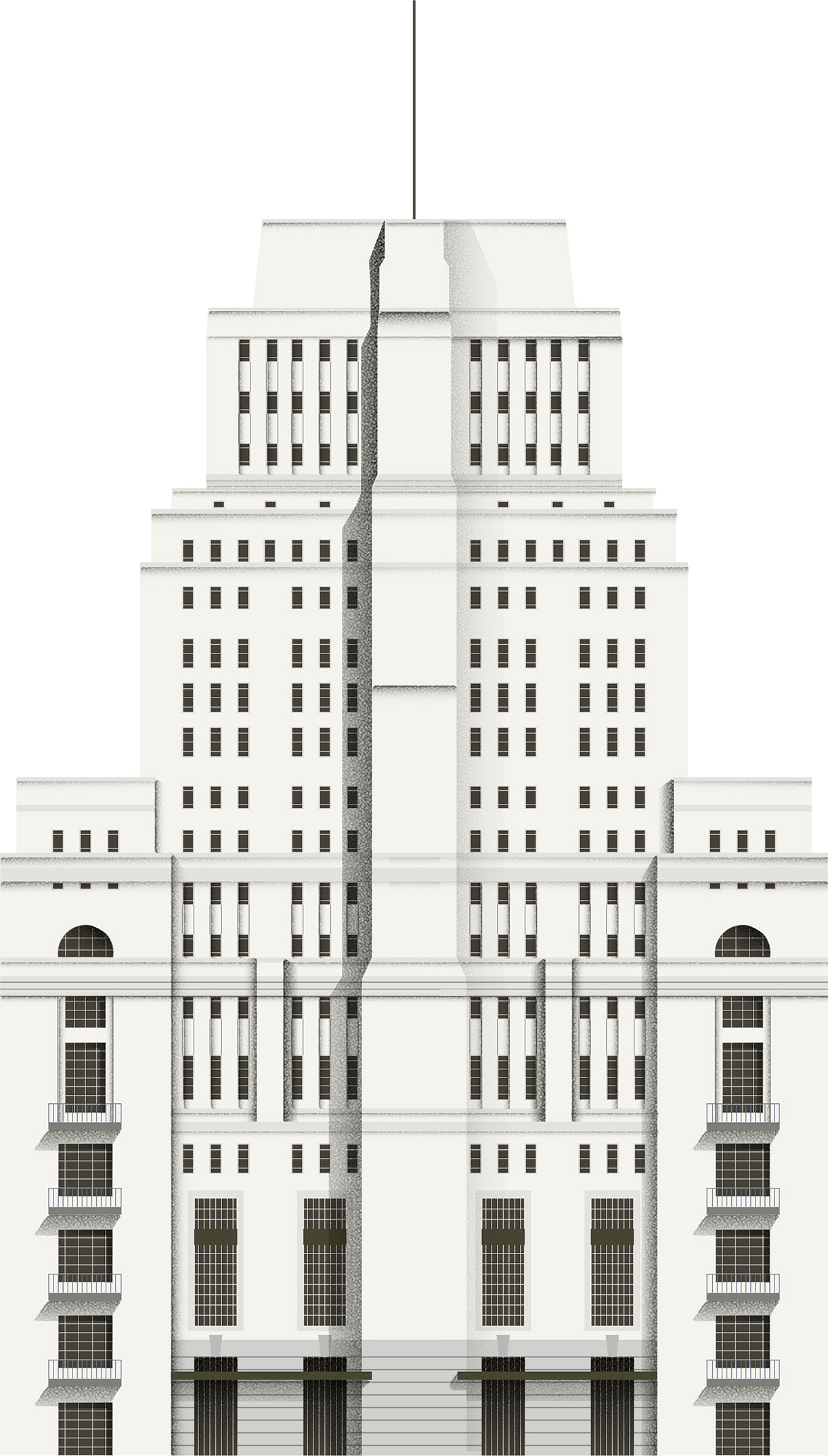

As London’s businesses opened their doors to the international market, so too did its education institutions. Senate House (027) in Bloomsbury was built by the University of London, the largest university in the world at that time. The university needed to expand and was also determined to improve its prestige globally. Charles Holden was chosen as the architect, partly because of his experience with 55 Broadway (008). The brief asked for a building that would stand the test of time and that wouldn’t go out of fashion once tastes changed.

027 Senate House

Charles Holden

1937

1937  WC1E 7HU

WC1E 7HU  64M

64M

When completed in 1937, Senate House became the tallest building in London, beating Shell Mex House (024) by six metres. The university’s vice chancellor fittingly described it as ‘something that could not have been built by any earlier generation than this, and can only be at home in London’. As with any new architecture, it wasn’t to everyone’s taste. The tower’s huge undecorated mass was intended to show the university as a permanent institution, but Londoners had other ideas. With war looming once again, people connected its style with strict Nazi architecture, and a rumour spread that Hitler desired it as his British headquarters.

However, as if to prove the rumour false, the Luftwaffe bombed the building during the Blitz. During the Second World War, the Ministry of Information moved in. Contrary to its name, the ministry’s main tasks were censorship, propaganda and manipulation of facts. Both the building and the institution inspired George Orwell’s all-controlling ‘Ministry of Truth’ in his anti-utopian novel 1984. Little surprise then that the building appeared in the film adaptation as well.

Austin ‘High Lot’ Taxicab

The first taxi designed especially for London. It earned its nickname due to the unusually high roof, which allowed passengers to keep their top hats on.