CHAPTER 3

The Egyptian-Israeli Rivalry, 1948–1970

The Egyptian-Israeli antagonism has played a central role in the Arab-Israeli conflict in the post–World War II era. It accounts for five wars (the Palestine War of 1948, the Sinai War of 1956, the Six Day War of 1967, the War of Attrition of 1969–1970, and the October War of 1973), numerous international crises, and most of the interstate casualties in the Arab-Israeli conflict. The rivalry emerged in 1948 during the Palestine War and began de-escalating after the October War in 1973, a process that continued in some respects through 1979 with the signing of the Egyptian-Israeli Friendship Treaty by Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin. It has never terminated completely, but it has definitely de-escalated to a point at which war between the two states seems unlikely, other things remaining equal. The first twenty-two years of this rivalry (1948–1970) were dominated by little or no change in Egyptian or Israeli leadership expectations that would result in new strategies for de-escalation. In this chapter we focus on the failed attempts to de-escalate the rivalry in the absence of expectational change through 1969.

The Emergence of the Rivalry during the Palestine War of 1948

Although the Egyptian-Israeli rivalry emerged in the Palestine War of 1948, we will start our discussion mainly with the rise of Nasser after the Free Officers Revolution in Egypt in 1952.1 Since our model is designed to understand rivalry de-escalation and termination, we are less concerned about the conditions that gave rise to the rivalry. However, we do want to acknowledge that the beginning of the rivalry in the Palestine War of 1948 is connected to Egypt's rivalries with other Arab states such as Jordan and Iraq and their struggle for dominance over Palestinian territory.

The decision by King Faruq of Egypt to go to war in 1948 was a byproduct of two major foreign policy challenges: eliminating British colonial presence in the country and containing King Abdullah of Jordan from accruing more Arab territory, not just in Palestine but in Syria and Lebanon as well. These two issues would continue to influence Egypt's rivalry relationship with Israel throughout the Nasser years as well.

Between 1945 and 1952, Faruq's foreign policy was consumed with the central issue of eliminating the British political and military presence from Egypt. Faced with rising pressure from radical groups demanding Britain's withdrawal, Egypt's leaders knew that their public legitimacy depended on their ability to advance a nationalist agenda. Unfortunately, the British were not prepared to leave an area that they deemed to be vital to their strategic concerns. Yet, Egypt had little power to oust the British, who occupied the Canal Zone, Cairo, and Alexandria with fifty thousand troops (McNamara 2003: 16).

In 1945, King Faruq directed his efforts at undermining Britain's influence not just in Egypt but in the region as well through the creation of the Arab League, a pan-Arab organization headquartered in Cairo. Within the Arab League, two blocs of Arab states had emerged: the Hashemite powers of Iraq and Jordan, who supported Britain's presence in the region against the Triangle Alliance, composed of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Lebanon, who wanted to eliminate it. Despite the cleavages, Egypt dominated the Arab League and infused its policies with pan-Arab, anti-Zionist, and anti-imperialist ideologies—all of which resonated deeply among the Arab masses. In addition, Faruq embraced the idea of creating a defensive bloc of Arab states in the context of the Arab League that would be completely independent of Western states and whose members would be responsible to the will of the majority (Doran 1999: 76–80).

Not only did the Arab League rally around an effort to contain if not eliminate the plans of Britain and its Hashemite allies, it also unified the Arab countries around the commitment to Palestinian self-determination. The “Consensus Position” of the Arab League called for the creation of a Palestinian Arab state with sovereignty over all Palestine, rejecting Jewish and Arab cantons within a single state. The league condemned partition as a solution and endorsed a Palestinian state with the Arabs as a majority. This policy negatively affected Britain's ability to find an Arab leader who would mediate a solution between Arabs and Zionists. When it was unable to maintain control over Palestine as civil conflict between local Arabs and Jews escalated, Britain referred the Mandate of Palestine to the United Nations in February 1947 (Doran 1999: 100–101).

At that point, the Arab national movement in Palestine and the neighboring Arab states refused to recognize the partition plan, and launched a war instead. Egypt intervened in the Palestine War of 1948 not so much to eradicate the new fledgling Jewish state as to stop Britain and its Hashemite allies of Jordan and Iraq from accruing more Arab territory in Palestine and adversely affecting the Arab balance of power in the region (Doran 1999).

The key issue for Egypt (as well as the other Arab states) was the kind of political authority that would replace the British in Palestine. King Faruq, along with Syrian and Saudi leaders (as members of the Triangle Alliance), believed that the British would endorse an agreement to partition Palestine between Jordan and Israel. They perceived that in return for King Abdullah's recognition of Israel's existence, Israeli leaders might support his plan for a Greater Syria.2 The evidence today indicates that for the most part they perceived correctly (Shlaim 2001b).

The Egyptians knew that the costs of nonintervention would have been too high. The Jordanians would have inevitably expanded into Arab Palestine and threatened to absorb Syria, or at best Syria would become someone's satellite. In either situation, the Triangle Alliance would no longer be a venue from which Egypt could dominate the Middle East. According to Doran (2001: 102), “alliance maintenance” dictated that Egypt enter the war so it could weaken Jordan and frustrate its plans for strengthening the British Empire. Moreover, Egypt was unwilling to leave the Palestine question to the exclusive machinations of Jordan, Israel, and the West (Doran 1999: 141).3

The Impact of the Palestine War of 1948: Israel Stonewalls

When the Palestine War was over, the Egyptians had suffered a major political and military defeat. Yet, during the course of the war, they were able to undermine Jordanian-Israeli cooperation, and the war left Jordan weak enough that it could no longer pose a threat to Syria. Nonetheless, the war also contributed to the destabilization of Syria, leading to three coups in 1949, and the Egyptians worried that Iraq and Iraq's supporters in Syria would seek a federation or failing that, that Israel would dominate Syria. Consequently, the Egyptians reaffirmed their commitments to pan-Arabism and their support for a regional defense system in the context of the Arab League. This Arab security pact was Egypt's ultimate grand strategy because its emphasis on Arab independence and pan-Arabism “tied together policies in all the major spheres of public life—the domestic, inter-Arab, Arab-Israeli, and great-power arenas” (Doran 2001: 103–104).

In 1949, Egypt signed an armistice agreement with Israel, regarding it as a temporary truce. Israel, in contrast, saw the armistice as a first step toward peace. By the 1950s, the Egyptian-Israeli conflict (like the general Arab-Israeli dispute) was centered on three issues: 1) Israel's return of border areas taken during the war of 1948; 2) the repatriation of over seven hundred thousand Palestinians to their homes; and 3) the internationalization of Jerusalem. While Israeli leaders were inflexible about making concessions on their new territorial gains and the fate of the Palestinian refugees, the Egyptians, like the Syrians and the Jordanians, were also unwilling to make concessions of their own, largely due to their fears about violent domestic repercussions should they sign any peace agreement with the Israelis (Oren 1992: 6).

Although publically the Egyptians appeared to be inflexible on these issues, privately they sought some accommodation with the Israelis. Between 1948 and 1952, the Egyptians and Israelis engaged in a series of secret contacts over the conditions of a final peace agreement.4 King Faruq made several secret overtures to the Israelis for a permanent peace agreement in exchange for all or parts of the Negev Desert, retention of the Gaza Strip, and an accommodation for the Palestinian refugees (Oren 1992: 95–99). Consistently, the Israelis turned down the offers for any territorial concessions or repatriation. The fundamental reason for this intransigence was Prime Minister Ben-Gurion's belief that “time was on Israel's side”: that with the passage of time, Israel's bargaining position would only improve; that the Arabs, the United Nations, and the Great Powers would eventually come to accept the status quo; and that the armistice agreement with Egypt was good enough to meet Israel's needs for “external recognition, security and stability” (Shlaim 2001a: 41–53).

For Egypt, its policies toward Israel would become more severely constrained as time passed. As anti-Zionism became synonymous with Arabism, Egyptian leaders and domestic revolutionary parties alike set a high priority on Palestine's liberation. Since Israel's very existence reminded Arabs of their military debacle and humiliation in 1948, Arab leaders, especially those that aspired to regional dominance, felt compelled to pursue increasingly more aggressive positions against Israel on behalf of the Palestinians in order to legitimize their own governments and censure those that were considered too soft. Consequently, the rivalry between Egypt and Israel over the next two decades became more and more entangled with the political struggle for Arab leadership in the Middle East (Oren 1992: 7).

Internal Shock in Egypt: The Free Officers Revolution of 1952 and the Rise of Nasser

In July 1952 the Free Officers of the Egyptian army overthrew King Faruq and established a new regime with Major General Muhammad Naguib nominally in charge.5 However, the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), which was dominated by younger, more radical Free Officers such as Gamal Abdal Nasser and Anwar Sadat, established the policies for the new regime. Although there was no single political view among the Free Officers, they established two primary goals for the regime: the elimination of the British military presence in Egypt and the implementation of major political and economic reforms. In January 1953 the RCC dissolved all political parties (including its nemesis, the Wafd party) and declared Egypt a formal republic six months later. In the middle of 1953, Nasser, as the leader of the RCC, began to marginalize Naguib from key policy decisions. In November, Nasser consolidated his political control over the government when he accused Naguib of conspiring with the Muslim Brotherhood and removed him from the presidency. At that point, Nasser assumed the office and held it until his death in 1970.

At the outset of their rule in 1952 and 1953, Naguib and the RCC were less concerned about Palestine and Israel than they were about ending British influence in Egypt, instituting national reforms, and securing Egypt's leadership position in the Arab world. Consequently, they participated in secret communications with the Israelis primarily to maintain the status quo and avoid another round of conflict (Oren 1992: 101–103). In short, Egypt preferred to maintain the “no war, no peace” status quo (Morris 1993: 271).

On the Israeli side, Prime Minister Ben-Gurion held high hopes for a new beginning in Egyptian-Israeli relations. In a major speech before the Knesset in August 1952, he maintained that there was no reason for political or military conflict between the two countries, and he followed his speech with a major peace initiative. However, Naguib and the RCC did not respond and Ben-Gurion suspected that the Egyptians were projecting an image of moderation that would enhance Egypt's ability to get arms and aid without first taking serious steps toward a settlement with Israel (Shlaim 2001a: 78).

However, a new development occurred in the first half of 1953 when Nasser took charge of the RCC's negotiations with Israel. Nasser sent a message indicating that Egypt was not departing from its pan-Arab policy on Palestine. However, he requested Israel's support in obtaining economic aid for Egypt from the United States and for its support in Egypt's efforts to terminate the British military presence in the Suez Canal Zone. Nasser also made it clear that he wanted these negotiations to remain secret (Shlaim 2001a: 79).

In response to Nasser's initiative, the Israelis extended a serious offer at reconciling the differences between the two countries. They were willing to provide economic assistance to Egypt by purchasing $5 million worth of cotton and other products if Egypt lifted its restrictions on the passage of Israeli oil tankers through the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aqaba. Next, the Israelis would be willing to advance their support for British withdrawal from the Suez Canal if the Egyptians first showed their commitment to pursuing better relations via a secret high-level meeting. Eventually, Nasser turned down Israel's offer to buy Egyptian cotton, but the RCC did look into the matter of easing restrictions for Israeli ships through the Suez Canal (Shlaim 2001a: 79–80).

Ben-Gurion reacted pessimistically. He believed that the Egyptians were asking for too much and giving too little in return. He sent a counterresponse that stated Israel would be willing to help with the Suez issue if Egypt allowed free passage of Israeli ships through the Suez and Eilat as well as commit to a secret high-level meeting, which was a crucial test of Nasser's intentions. The Egyptians made no formal reply, and later Israel would learn through its Egyptian contacts that Nasser had decided not to pursue a request for Israel's help in securing U.S. economic aid because he did not want to incur an obligation. He also decided to bypass the secret meeting until the Suez dispute with the British was resolved. Afterward, the Israelis perceived that the RCC and Nasser had not been serious about pursuing peace negotiations, and by the end of 1953, Israel's high hopes for better relations had begun to disappear (Shlaim 2001a: 81).

Two External Shocks Intensify the Egyptian-Israeli Rivalry

Gaza Raid of February 28, 1955

In 1955, two foreign policy shocks significantly altered the relations between Egypt and Israel. The first shock emerged from increasing cross-border infiltrations from the Gaza Strip. By 1955, the frequency of these border incursions was posing serious day-to-day security problems for the Israelis, who were never really sure about treating them as isolated events or interpreting them as indicators of a more hard-line Egyptian foreign policy. The second shock occurred when Egypt signed a Soviet-backed arms deal with Czechoslovakia worth $320 million. Israeli leaders perceived that the deal altered the military balance of power, and they were convinced that Nasser was getting ready for a second round of war (Tal 1996).

Before the Egyptian-Czech arms deal, the Israelis were more concerned with upholding the status quo and protecting Israeli civilians and property along the border areas controlled by Egypt. In an effort to compel the Egyptians to take stronger preventive measures that would stop the infiltrations, the Israelis settled on a policy of reprisals. Generally, the lion's share of the border incursions from Gaza involved Palestinian refugees who traveled into Israel to visit relatives, seek food, harvest crops, or steal from Israeli work projects. A smaller number of these crossings involved Palestinian activists who engaged in sabotage and murder for the purpose of challenging the armistice lines and keeping the general conflict with Israel alive. Eventually, Egyptian intelligence agents and some soldiers participated in these crossings as well. In response, the Israelis pursued a reprisal strategy that shifted from initially killing individuals caught in Israel, to raiding Arab villages in Gaza, and in 1954 attacking Egyptian military forces both in Gaza and the Al-Auja demilitarized zone.6 Over time, the escalation of border crossings and reprisals culminated in a very controversial attack by Israel against Egyptians troops in Gaza on February 28, 1955. In that attack, Israeli troops killed thirty-eight Egyptian soldiers (Morris 1993; Tal 1996).

The Gaza raid was a major turning point in Egyptian-Israeli relations that ended the possibilities of any settlement.7 The scale and damage of the operation both shocked and humiliated Nasser and his armed forces. Until this time, Nasser had maintained a consistent and firm policy of curbing Palestinian infiltration from the Gaza Strip in an effort to keep the border areas quiet and maintain the status quo (Morris 1993; Shlaim 2001a). After the raid, Palestinian refugees engaged in three days of violent demonstrations and riots against Egyptian and UN buildings and jeopardized Nasser's control over Gaza. Not only did the raid endanger Nasser's domestic political position, it also altered Nasser's perceptions of the Israelis. He no longer believed in the possibility of coexistence with Israel and he felt personally responsible for the Egyptian casualties. He also maintained that the raid had hurt his regime's prestige, and his military government could not suffer such a defeat again without retaliation (Morris 1993: 328–329).

At this point, Nasser changed his policy of curbing and repressing cross-border infiltration to one that would allow the refugees to engage in militant actions that fell short of war. Now, he supported retaliatory strikes against Israel and he unleashed a series of raids and counterraids against Israeli targets. More importantly, Egypt embarked on a policy of recruiting and organizing fedayeen units in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria to raid Israeli targets from third countries (Shlaim 2001a: 125–127).

In August and September 1955, the border clashes between Egypt and Israel peaked with Israel's attack in Khan Yunis in Gaza, which killed seventy-two Egyptians and Palestinians. These heavy casualties coupled with pressure from the United States convinced Nasser to back off and pursue different options:8 tighter restrictions in the Straits of Tiran against Israeli shipping, the closure of air space over the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli aircraft, and support for more third-party infiltrations by fedayeen in other Arab countries (Morris 1993: 327–350).

On the Israeli side, the Gaza raid in February 1955 signaled a shift in Israeli policy. After returning to the Defense Ministry in 1955 (after a two-year hiatus from the government), Ben-Gurion believed that Nasser was an “implacable and dangerous enemy” and argued that Prime Minister Sharett's conciliatory policies had to end (Shlaim 2001a: 123).9 Within days of his return to office, Ben-Gurion inaugurated a tougher approach by approving the Gaza raid in February. He worried that Nasser's ascendancy in the Arab world represented a serious threat to Israeli security. Therefore, he hoped to use a military operation to weaken Nasser by exposing his military's weaknesses. He argued that it was important to display Israel's military superiority over the strongest Arab country as well as bolster the confidence of the Israeli public and army (Shlaim 2001a: 125). According to Tal (1996: 64), Israel's decision to launch the Gaza raid also occurred against a backdrop of important events that undermined Israel's sense of security, particularly Egypt's success in negotiating the withdrawal of British troops from the Suez Canal in 1954.10 Israelis also feared that the United States would provide economic and military assistance to Egypt in its efforts to entice Nasser to join a regional defense system and that Egypt would use the arms against Israel.

The Egyptian-Czech Arms Deal of 1955

Another major shock to Egyptian-Israeli relations was the $320 million Soviet-backed arms deal between Egypt and Czechoslovakia.11 The Gaza raid played a significant role in Nasser's decision to negotiate an arms deal in May 1955, with the first deliveries reaching Egypt in July (McNamara 2003; Morris 1993; Shimshoni 1988). Since the raid demonstrated Egyptian military inferiority vis-à-vis the Israeli Defense Forces, Nasser searched more aggressively for military arms to equalize the situation.12 When the United States and Britain refused to comply, Nasser turned to the Eastern Bloc.13 Although the Gaza raid was an important factor, other scholars suggest that it was more a pretext than a cause for the arms deal (Bar-On 1994; Shlaim 2001a; Doran 2001). Actually, Egypt's arms deal had to be considered in a wider inter-Arab context; namely, the Gaza raid also coincided with the formal signing of the Baghdad Pact between Turkey and Iraq in February 1955 with Iran, Pakistan, Great Britain, and hopefully Jordan joining soon after.14

The Baghdad Pact threatened to undermine Egypt's long-term efforts to eradicate Britain's regional security system, and it damaged Nasser's efforts to secure a leadership role in the Arab region.15 He believed that the United States and Great Britain would expand the regional role of Jordan and Iraq, and even bring about the Greater Syria project, at the expense of Egypt and the Arab League. In short, the Baghdad Pact renewed the competition between the Egyptian-led Triangle Alliance and the pro-British Hashemite states for Arab leadership. Nasser secured the Egyptian-Czech arms deal in an attempt to establish greater independence from Britain, destroy the Baghdad Pact, and ensure the eradication of Britain's military presence from the region. Rhetorically, Nasser explained to his constituents both at home and in the region that the Baghdad Pact represented “perpetual subservience to Zionism and imperialism,” while the Arab League led by Egypt would be faithful to the priorities and values of the Arab world (Doran 2001: 108). Hence, the attempts by the Great Powers to build an anti-Soviet regional defense system encouraged Nasser to be more aggressive in asserting his pan-Arab leadership, which produced a more hard-line policy vis-à-vis Israel.16

For Israel, the Egyptian-Czech arms deal was a “watershed” development in Israeli-Egyptian relations because it immediately changed the prevailing balance of power. Israeli military planners estimated that Egypt's arsenal would now be three times larger than what Israel had or expected to get in the short term. However, they were more concerned about the qualitative shift in the military balance of power. The newer sophisticated Soviet weapons challenged the Israelis' view that their technological superiority could overcome any numerical advantage that the Egyptians had. Since these weapons deprived the Israelis of a “deterrent effect,” Nasser was likely to exploit the situation and attack Israel as soon as his army had absorbed the weapons. Ben-Gurion and his military planners believed that the Egyptians were likely to attack as early as the summer of 1956 (Bar-On 1994: 17–18; Morris 1993: 277).17

Arms Buildup and the Sinai War in 1956

When Britain and the United States refused to abrogate the Tripartite Agreement of 1949,18 the Israelis turned to France, which agreed to sell arms, primarily because of French antagonism toward Nasser, who was sending arms to Algerian nationalists. The French hoped that if Israel could eliminate Nasser, the Algerian rebellion would collapse (Shlaim 2001a: 163). In July 1956 the Israelis signed a contract with the French to purchase $51 million of French arms, including 36 jets, 210 tanks, and 100 guns (Oren 1992: 91). After the Israelis contracted for arms with the French, Nasser successfully negotiated a second round of weapons with the Soviets for more aircraft jets, much to the dismay of the United States.

Meanwhile, the United States tried to mediate a comprehensive peace settlement between Israel and the Arabs (for example, the Alpha Project), but it failed to produce any tangible results. The final breach of good relations between Egypt and the United States and Britain occurred at the end of 1955 when Jordan became the battleground over the Baghdad Pact. After King Hussein showed a willingness to join the pact, Nasser and the Saudis generated widespread demonstrations in Jordan that prevented Hussein from joining. At this point, the United States, believing that Nasser was opposed to its interests in the area, withdrew its funding for the Aswan Dam on July 19, 1956. On July 26, Nasser nationalized the British- and French-owned Suez Canal. During the same time period (the summer of 1956), the Israelis began to prepare for a “preventive war” and through their talks with the British and the French signed onto to a joint military operation that would initiate the Suez War on October 29, 1956 (McNamara 2003: 53–59).

Within days, the Israelis achieved a complete military victory. The Egyptian forces withdrew from the Sinai and the Gaza Strip, leaving six thousand soldiers behind, which minimized their losses to the army. By November 2 the Israelis had captured Gaza and three days later all of the Sinai was in their hands. During the war, Eisenhower pressured the British, the French, and the Israelis to cease their military operations.19 In particular, he demanded an unconditional Israeli withdrawal and threatened to cease all U.S. government and private aid to Israel if it failed to do so. However, four months later, the United States negotiated a deal that would ensure Israel's right to navigate the Straits of Tiran and the Red Sea. The United States went so far as to say that if Egypt renewed its blockade, Israel had the right to use military force in the interest of “self-defense” (Shlaim 2001a: 181–183).20

The Impact of the Sinai War (1956–1966): Egypt and Israel Continue Hard-line Policies

According to Shlaim (2001a: 183), the Israelis had three military objectives—all of which they achieved—and three political ones—none of which were completely successful. On the military front, the Israelis defeated the Egyptian army quickly, and their victory reestablished their superiority and their deterrent capability in the Middle East. Regarding the international waterways at the Straits of Tiran, U.S. guarantees assured that Israeli shipping would not be curtailed. Since Israel had destroyed the fedayeen bases in Gaza, fedayeen attacks across the border ceased. Moreover, the Egyptian forces did not return to their bases in the Sinai. In that respect, the Sinai became “demilitarized.” Israel was able to experience eleven years of relative border peace and stability with Egypt.

Nonetheless, on its three political objectives, the results were mixed. The Sinai War did not result in the overthrow of Nasser; instead, Nasser emerged with even more prestige and influence in the Middle East and the periphery. Next, the Israelis were not able to extend their borders. Nonetheless, the war gave Israel “unqualified sovereignty” within these borders and the quarrel with Egypt over the interpretation of the armistice agreement of 1948 was settled in Israel's favor (Bar-On 1994: 319). Finally, Ben-Gurion had hoped that war would bring down or weaken the governments in Lebanon, Iraq, and Egypt to such an extent that each of them would make peace with Israel on its terms. Instead, the war of 1956 solidified pan-Arab commitments to resolving the Palestine problem while the countries in question worked on changing the military balance of power with Israel (Shlaim 2001a: 183–185).

The war did convince Ben-Gurion to accept the territorial status quo outlined in the armistice agreement of 1949. Adopting a strategy of deterrence that would discourage Egypt and its allies from changing the territorial status quo through military force, he upgraded Israel's military capabilities significantly to ensure a qualitative advantage over his Arab rivals. He also sought international diplomatic guarantees for Israel's security. He was especially worried about the Soviets extending their influence in the region through their military and economic support for radical Arab regimes that were most hostile to Israel's security (Shlaim 2001a: 189).

As for Nasser, he emerged from the war without a clear strategy vis-à-vis Israel. Instead, he opted for a policy of hostility short of war: economic boycotts, strategic blockade (via the Suez Canal), sporadic Egyptian-supported guerrilla attacks by Palestinians, political warfare in the international community, and continued pressure on Israel to allow Palestinian refugees to return home. In short, he confined the Palestinian problem to international diplomacy and he avoided situations that increased the risks of war with Israel (Sela 1998: 52–57).

Throughout the late 1950s and until May 1967, Nasser repeatedly argued that the war against Israel needed to be postponed in order to give Egyptians and other Arabs the time to build up their military, economic, and political capabilities (Sela 1998: 52). Instead, he preferred to concentrate on consolidating his socialist economic revolution at home and creating a unified Arab regional hegemony through his support for pro-Nasserist parties and governments throughout the Middle East. At home, Nasser initiated a state-led import-substitution industrialization policy that was financed by nationalizing the nonagricultural private sector of the economy and relying heavily on external aid from abroad.21

On the regional front, Nasser was busy extending his vision of pan-Arab unity throughout the Arab Middle East. His regional efforts culminated in 1958 with the Egyptian union with Syria, whose regime was also a socialist government closely aligned with the Soviet Union. The unification—resulting in the establishment of the United Arab Republic—was a high point for Nasser's regional foreign policy. However, by 1961, a military coup in Syria had ended the union, and Nasser embarked on a more radical regional policy that supported internal revolts against conservative regimes in Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia. In October 1962, Egypt intervened in the Yemeni civil war, which rapidly escalated to a protracted five-year proxy war between Egypt and Saudi Arabia. At this point, Nasser had little interest in confronting Israel.

Israeli-Syrian Clashes and the Escalation to the Six Day War in 1967

Ironically, the Egyptian front with Israel was peaceful for a full decade after the Sinai War, primarily as a result of Nasser's military commitments in Yemen and his preoccupation with inter-Arab struggles. The most serious border conflicts in the 1960s occurred between Israel and Syria over the Golan Heights. Two particular issues were at stake: control over water resources from the Jordan River within the demilitarized zones between Israel and Syria, and military attacks from Palestinian guerrilla organizations (Shlaim 2001a: 228).

Throughout the 1950s and in the early 1960s the Israelis engaged in provocative military raids against the Syrians in an effort to capture areas within the demilitarized zones for the purpose of diverting the Jordan River for a major irrigation project in the Negev and gaining control over the Golan Heights in order to enhance their security against Arab infiltrations and shellings of Israeli settlements (Slater 2002: 90; Shlaim 2001a: 235–236).22 According to Shlaim (2001a: 235), Israel's clash with the Syrians was “probably the single most important factor in dragging the Middle East to war in June 1967.”

In early February 1966, an intraparty military coup produced a more radical regime in Syria. The new Ba'thist government, frustrated with the lack of containing Israeli aggression through the UN Security Council, decided to take stronger retaliatory actions against Israel. As the Syrians escalated their clashes with the Israelis, they also encouraged Palestinian guerrilla attacks against Israeli targets. Between February 1966 and May 1967, Syria initiated 177 border incidents and 75 Palestinian guerrilla raids inside Israel (Ma'oz 1995: 89–93).

The escalating hostilities between Israel and Syria increased Soviet and Egyptian fears that a war with Israel could harm the new regime at the same time that it could drag Nasser into a war that he wanted to avoid. Consequently, the Soviets negotiated a rapprochement between Egypt and Syria that ended in the signing of a mutual defense pact in November 1966. For Nasser, the defense pact was designed to diminish Syria's insecurities about Israeli aggression and provide him with greater leverage to diminish Syria's use of force against Israel. Nonetheless, the Syrians refused to back down. They continued to support Palestinian guerrilla actions against Israel, rejected Egypt's offer to deploy its air force units on Syrian soil for added protection, and demanded that Nasser remove the UN Emergency Force (UNEF) troops from the Sinai (Sela 1998: 89–90).

In early 1967, the Israelis resumed their activity in the demilitarized zone, provoking clashes with the Syrians, and on April 7 the Israeli air force shot down six Soviet-made Syrian MiGs but not before penetrating Syria and flying over Damascus, humiliating the Syrian military. On May 12, 1967 Israel's defense minister, Yitzhak Rabin, threatened to overthrow the Syrian regime in a news interview. Although the Israelis quickly repudiated Rabin's comments, the Soviets became concerned and intervened in the crisis by sending a report to Nasser that Israel was mobilizing its forces on its northern border and planning to attack Syria. Although the report was false and Nasser knew it, he mobilized his troops into the Sinai on May 14, 1967. Next, he asked the United Nations to remove the UNEF troops from the Sinai, and on May 22, 1967, he closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping and expressed his willingness to go to war with Israel (Sela 1998: 87–90; Shlaim 2001a: 236–237; Feiler 2003: 196). Nasser believed his military's assessment that Egypt could withstand an initial military attack from Israel and launch a stronger counteroffensive that would significantly weaken Israel. He also believed that fighting between Egypt and Israel would end early due to the inevitable intervention from the United States and the Soviet Union, thus preserving Egypt's position in the straits (Feiler 2003: 203–204).

Although Nasser reiterated frequently that war with Israel should be postponed until the Arabs were stronger, he embarked on a “defensive strategy” while hoping that the United States or the Soviet Union would intervene to halt the conflict. Scholars maintain that Nasser's decision to risk a war with Israel is best explained by his declining leadership in the Arab world. After 1964, Nasser experienced heavy criticism from his Arab rivals about his unwillingness to confront Israel aggressively and his cowardice of hiding behind UN forces in the Sinai. Moreover, Nasser's defense commitment to Syria added more pressure on him to preserve his prestige and credibility. When Nasser mobilized his forces in the Sinai, Arab public opinion demanded even more militancy, and he complied by removing the UNEF troops from the border. Finally, his decision to blockade the Straits of Tiran constituted a “casus belli” for the Israelis. Two weeks later, the Israeli government launched a massive air and ground attack against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, and within days Israel had defeated all of their military forces (Sela 1998: 92–93). At the end of the war, Israel had more than doubled its size, capturing the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights, and the Jordanian-held West Bank, including all of Jerusalem.

The Impact of the Six Day War of 1967: No Overall Change in Egyptian-Israeli Relations

In Egypt's case, the military defeat in 1967 produced within the Egyptian national leadership two strategic alternatives to Israel. One approach was to pursue a political solution with the aid of the United States, which would be inclined to intervene in order to check the Soviets' increasing influence in the Middle East. The other approach was based on the presumption that a political solution was pointless and that only a buildup of military power would lead to a solution; the buildup would not necessarily be for war, but would serve as a means of convincing the Israelis that a just solution would have to be based on a balance of interests and on the principle that “what was taken by force would be returned by force” (Shemesh 2008: 353). Nasser opted mostly for the second solution but not without discarding a political approach altogether. Eventually, he would pursue a military option that would be complemented with a political approach.

At the inter-Arab conference in Khartoum in September 1967, Nasser was able to convince the Arab states to support a two-staged solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. The first stage would involve the return of Arab territories that Israel occupied after the Six Day War, and the second stage would involve the goal to achieve the liberation of Palestinian lands and the creation of a Palestinian government. The summit meeting in Khartoum represented a “watershed” in terms of securing a solution in stages and in terms of pursuing a political path. The view held by Nasser and other Arab leaders was that it would take a long time before the first stage could be achieved by military means. Hence, they were more flexible about pursuing a diplomatic path (Shemesh 2008: 243).23 Nasser even encouraged King Hussein to explore the possibility of negotiating a return of the West Bank and East Jerusalem to Jordan, although the Israelis did not know this at the time (Shlaim 2001a: 259).

More evidence of Nasser's willingness to pursue a political option was his agreement to accept the UN Security Council's Resolution 242 in November 1967.24 In Nasser's view, this agreement laid the foundation for implementing the first stage of the Arab/Egyptian strategy conceived at the summit in Khartoum. Nasser's support of the UN resolution also led to the UN-sponsored Jarring mission from 1967 to 1969.25 Such efforts also increased a dialogue between Egypt and the United States, which Nasser hoped would lead to U.S. pressure on Israel to withdraw its forces from newly gained Arab territory (Sela 1998: 108; Shemesh 2008: 243).

Despite these diplomatic overtures, Nasser also maintained a pragmatic but hard-line policy toward Israel, especially in light of growing domestic unrest over Egypt's military defeat, the deterioration of the economy between 1967 and 1970, and increased government repression and authoritarianism. In the midst of this internal turmoil, Nasser decided that recovering the Sinai had the highest priority, and he also believed that the only means to secure it was through another round of war with Israel. He perceived that war would not only redeem his declining prestige in the region but also shore up his political legitimacy at home. Hence, he refused to make any deals with Israel that entailed an exchange of the Sinai for a final peace agreement. Instead, he opted for a policy of rebuilding his armed forces but not without sending a clear message that he was open to negotiations that would result in the unqualified return of the Sinai even if it came at the expense of the Palestinians (Sela 1998: 97–99). But, for the short term, Nasser was interested in rebuilding his army and searching for a massive infusion of economic assistance to overcome the financial shortfalls associated with the war: closure of the Suez Canal, the decline in tourism, and the loss of the Sinai oil fields. It is estimated that the Egyptian economy lost $219–$230 million just with the closing of the Suez Canal alone (Feiler 2003: 174).26

The most significant impact that the Six Day War had on Nasser's foreign policy was the shift in his Arab regional policy. While at the conference in Khartoum, Nasser made peace with the oil-rich, conservative Arab governments by eschewing his pan-Arab radicalism in favor of championing an anti-Zionist movement in the Arab world. He argued successfully that as a front-line confrontation state against Israel Egypt needed significant amounts of financial aid to prepare it for the next round of warfare. In exchange for his withdrawal of Egyptian troops from Yemen,27 his moderation of his revolutionary ideology, and his decision to move away from a strict socialist control over the Egyptian economy, Kuwait, Libya, and Saudi Arabia provided $257 million a year indefinitely—a figure that was 10 percent higher than Egypt's estimated losses (Feiler 2003: 7).28 This Khartoum aid to Egypt continued even after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1975 and lasted until March 1979, when an economic boycott was levied against Egypt in retaliation for Egypt's participation in the Camp David Accords in 1978. In addition to funds from the oil-rich Arab states, Nasser also obtained more arms from the Soviets, who expanded their support from $424 million in weapons from 1963 to 1966 to $2.23 billion from 1967 to 1973 (Barnett 1992: 114–115). With a new infusion of foreign assistance, Nasser prepared for war since he perceived that the Israelis were unlikely to give up the Sinai voluntarily.

As for the Israelis, they debated the merits of a peace offer to the Egyptians in exchange for the demilitarization of the Sinai and security guarantees for Israeli rights of passage through the Suez Canal, the Straits of Tiran, and the Gulf of Aqaba.29 After the Khartoum conference, however, the Israelis canceled the offer when the Arabs concluded their meeting with the famous three nays: no peace, no recognition, and no negotiations with Israel (Shlaim 2001a: 258). Although moderate Arab leaders won the day at the Arab summit by calling for a political solution rather than military means to seek Israeli withdrawal, the Israelis saw only a hard-line policy. At this point, they decided that Israel would maintain the status quo as determined by the ceasefire agreements and reinforce its position according to its security and development needs. More ominously, Israeli leaders secretly canceled the principle of seeking peace with Egypt on the basis of the international border in favor of one based on secure borders (Shlaim 2001a: 259).

But, the three nays at the Khartoum conference were not the only reason Israel decided to pursue a hard-line policy. By January 1968, a new coalition of political parties, referred to as the second labor alignment, was dominating the government under Prime Minister Levi Eshkol. The new Labor Party incorporated a wide range of views on Israel's foreign policy—some of which were committed to territorial compromise, some of which wanted to preserve Israel's hold on all the territories or simply expand its control over the West Bank. The wide diversity of views made it difficult for the Israeli government to pursue negotiations seriously without alienating a key faction and bringing down the government. Hence, the lack of consensus within the governing coalition contributed to the government's immobilization on foreign policy initiatives (Shlaim 2001a: 262). After Golda Meir became prime minister in March 1969, the hawks, who were opposed to any territorial compromise, disproportionately dominated her cabinet, and Israeli foreign policy consisted of “military activism and diplomatic immobility” (Shlaim 2001a: 289). Meir preferred the status quo over domestic political costs that might be incurred through diplomacy and compromise. Therefore, she refused to shift from the ceasefire lines of 1967 until the Arabs accepted a peace agreement on Israel's terms. According to Shlaim (2001a: 289), “intransigence” was not only Meir's middle name; it was also the hallmark of Israel's policy toward the Arabs for the next five years.

The Impact of the War of Attrition, 1969–1970: No Change in Rivalry Relations

After the Six Day War, Nasser moved ahead with his plans to rebuild his armed forces. He concentrated on reorganizing the army, adding three divisions to his ground forces, centralizing its leadership, and retraining and reeducating his soldiers. Moreover, he invested tremendous resources in his air defense and air force primarily through Soviet aid.30 By early 1969, Egypt had restored its prewar strength and expanded its combat aircraft. Although it had a greater number of planes than Israel, its pilots were not as skilled as the Israelis, which ruled out a direct frontal assault against Israel. Instead, Nasser opted for a limited war against Israel along the Suez Canal area with the aim of inflicting large numbers of casualties over time. Nasser's goal was to prevent the solidifying of the military status quo after the Six Day War and to pressure the international community to force Israel to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and other occupied Arab territories (Yaqub 2007: 38).

In return, the Israelis settled on a “defensive strategy” of preventing the Egyptian army from crossing the Suez Canal and capturing territory on the east bank. Hence, they built a line of fortifications along the canal (for example, the Bar Lev Line) where they concentrated their military forces. At the beginning of 1970, the Israelis shifted to a strategic bombing campaign against Egypt's inner cities. The Israelis anticipated that the bombing would bring the war to an end and compel Egypt to recognize the ceasefire. On a political level, they expected that the deep penetration bombing would break Egyptian morale, bring about Nasser's political demise, and produce a pro-Western successor. Between January and April 1970, Israel flew thirty-three hundred sorties and dropped an estimated eight thousand tons of ordnance on Egyptian territory (Shlaim 2001a: 291–294).31

When Nasser embarked on what became the War of Attrition, he failed to anticipate that Israel would counter with strategic bombing campaigns deep in Egyptian territory. The costs were in some cases higher than the Six Day War in 1967. For instance, the death toll exceeded the last war, and Israel's destruction of the Suez Canal cities produced a massive population exodus to Cairo, where many of the displaced became unemployed and impoverished. The military stalemate in the war combined with increasing economic burdens influenced Nasser to appeal to the United States to intervene in the conflict and force Israel to withdraw from the occupied Arab territories. In July 1970, Nasser accepted the U.S.-backed Rogers Plan for a ceasefire of hostilities along the Suez Canal military zones and the resumption of a UN peace mission. Shortly afterward, the Israelis also agreed to the plan (Feiler 2003: 177; Yaqub 2007: 42).

The State of the Egyptian Economy by the End of the 1960s

By the time of Nasser's death in September 1970, Nasser's Five Year Economic Plan in 1960 had failed to generate economic development and growth as it was intended to do. By the mid-1960s, the Egyptian economy was characterized by several ominous trends: a) increasing public consumption at the expense of domestic investment; b) rising trade imbalances due to poor export performance; c) growing defense outlays associated with war against Israel that constituted as much as 20 percent of Egypt's GDP in 1973; and d) a series of external shocks that undermined economic growth—for example, the failure of the cotton crop in 1961, the costs of the Yemeni civil war (1962–1970), and suspension of U.S. food imports (Kenawy 2009: 591; Waterbury 1983: 91–93). As a consequence, Nasser had to rely more frequently on external debt financing especially after the Six Day War of 1967.

Although aid from the Soviet Union increased, it was unable to compensate for the reduction in Western aid. The main source of external aid after 1967 came from the Arab oil countries as a result of the Khartoum agreement in 1968. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Libya provided $286 million on average annually. Although this aid was significant, Nasser faced another set of economic burdens, which included newly emerging payment deadlines for loans taken for ambitious development projects before 1967. These payment installments amounted to $240 million annually from 1967 to 1972. Refusing to undertake more economic reforms that would reduce public and private consumption, Nasser continued to pursue policies that would regain the Sinai from Israel and restore Egypt's lost prestige. This strategy came at the expense of future economic growth and growing foreign indebtedness (Waterbury 1983: 98–99). In short, at the time of Nasser's death in September 1970, the Egyptian economy was on the verge of bankruptcy.

The Application of the Expectancy Revision Model to the Egyptian-Israeli Rivalry of 1948–1970

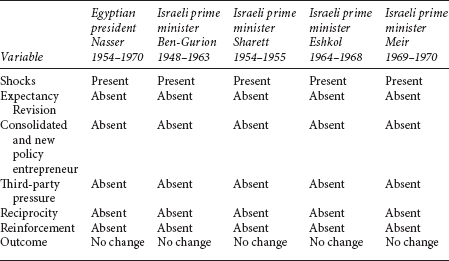

Table 3.1 outlines the key variables of our model. It shows that while Nasser had consolidated his political control over Egyptian institutions as president during the years 1950–1970, he remained inflexible in the presence of internal and external shocks and the absence of third-party pressure, reciprocity, and/or reinforcement toward de-escalation from Israel.

On the Israeli side, the years 1950–1970 are associated with four Israeli prime ministers—only one of whom was clearly in charge of Israel's foreign policy without any serious domestic constraints and that was David Ben-Gurion, who monopolized the policymaking in determining Israel's security strategies and national priorities from 1948 to 1953. Although his reign as prime minister was interrupted for two years (1954–1955), Ben-Gurion was able to reestablish his control over Israel's foreign and defense policies largely as a result of Israel's successful involvement in the Sinai War of 1956. He was an indisputable leader because he was able to win majorities in the Knesset and his cabinet at will (Shlaim 2001a: 187). He also dominated the Israeli Defense Forces by appointing a military chief-of-staff, Major General Chaim Laskov, in 1958; Laskov stayed out of politics and deferred to Ben-Gurion's policies. Hence, in the years 1958–1963, Ben-Gurion again enjoyed a near monopoly over Israel's foreign and defense policies (Shlaim 2001a: 187–188). Nevertheless, this policy control never corresponded with a sea change in Ben-Gurion's views of Egypt or those of his successor. Table 4.1 in Chapter 4 also indicates that while none of the four Israeli prime ministers in the years 1950–1970 had changed their expectations about their Egyptian counterpart, there was also an absence of reciprocity and reinforcement from the Egyptians and a lack of international third-party pressure despite the presence of major internal and external shocks during the regimes in question.

Table 3.1. Modeling Outcomes for the Egyptian-Israeli Rivalry, 1948–1970

Note: Ben-Gurion served 1948–1953 and 1956–1963; Meir served 1969–1974.

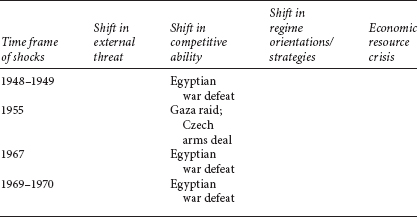

Between 1952 and 1970, the shocks, outlined in Table 3.2, emanated from the external, regional environment rather than from major developments internal to either Egypt or Israel. Unfortunately, they reinforced rather than changed preexisting and future expectations of threat on both the Egyptian and Israeli sides. The Israeli raids into Gaza in 1955, the Sinai War in 1956, the Six Day War in 1967, and the subsequent War of Attrition in 1969–1970 only hardened Nasser's views toward the Israelis and vice versa. The severe deterioration of the Egyptian economy might have had an inhibitive effect in other circumstances, but just enough foreign assistance was forthcoming to allow decision makers to evade its policy implications. Egypt's race to build up its military capabilities, its support for Palestinian covert operations against Israeli targets, and its bellicosity prior to the Six Day War in 1967 created a perceived opportunity for Israel to win another war and hopefully dismantle Nasser's regime.

Table 3.2. Shocks in the Egyptian-Israeli Rivalry, 1948–1970

The expectancy model also stresses the key role that policy entrepreneurs play in overturning preexisting policy monopolies held by opposing factions inside and outside their governments. Policy entrepreneurs are able to bring about fundamental shifts in their foreign policies because they are well positioned to push new thinking and policies through these opposing forces. In short, policy entrepreneurs have the necessary support of their domestic constituencies to support such changes. However, the presence of policy entrepreneurs does not always correlate with dramatic changes regardless of their political influence and their control over their domestic constituencies or bureaucracies. For instance, Nasser had consolidated his political control over the Egyptian government by 1953 and he enjoyed widespread public support. However, this position did not translate into new directions in Egyptian foreign policy, and despite the numerous shocks that adversely affected Egypt both regionally and domestically, Nasser refused to move in fundamentally new directions. As for the Israeli prime ministers between 1952 and 1970, only Ben-Gurion was in a position to monopolize foreign policy and he also refused to change his thinking despite continued reinforcement that hostilities between Israel and Egypt were not de-escalating in the face of Egypt's military defeats.

The key actors in this period were the United States and the Soviet Union, but neither of them took an overt diplomatic position to resolving the conflict. Their Cold War hostilities played out in the set of alliances that the United States and the Soviet Union established in the Middle East, which overlapped with the Arab-Israeli conflict. For Nasser, U.S. alliances with his Arab and Israeli competitors blocked any potential efforts that the United States could have undertaken to reduce the rivalry. Moreover, the United States had little incentive to pressure the Israelis to change their policies in light of Egypt's close ties to the Soviet Union and its fear of growing Soviet influence in the area. The Soviets in turn extended foreign aid and military arms to its allies, particularly Egypt and Syria, who clashed repeatedly with Israel. Besides intermittent efforts by the United Nations, there was little sustained diplomatic effort by the superpowers to negotiate a rapprochement between Egypt and Israel in light of the Cold War cleavages in the region.

There was one overture that had the potential to lead to more cooperation, but it failed to be pursued by either Egypt or Israel. During his early years, Nasser explored the possibility of cooperation with Israel for securing economic aid from the United States and influencing the British to leave the Suez Canal in 1953. However, Nasser failed to reinforce his offer of cooperation either publically or by offering to reduce restrictions for Israeli ships going through the Suez Canal. Consequently, the Israeli government under Ben-Gurion did not pursue any more diplomatic efforts. This state of affairs continued until 1970, when Anwar Sadat of Egypt undertook a significant peace initiative—the focus of the next chapter.