Democrats: Sweaty, disorderly, offhand, imaginative, tolerant, skillful at give-and-take.

Republicans: Respectable, sober, purposeful, self-righteous, cut-and-dried, boring.

Clinton Rossiter, Parties and Politics in America

Politics is a blood sport where fights among spectators can be just as ferocious as the blows traded by combatants. Political exchange tends toward the emotional and primal rather than the reasoned and analytical, which is why it must have seemed like a good idea to ABC News in 1968 to televise a series of debates between William F. Buckley, Jr., and Gore Vidal. Both were ideologues— Buckley for the right, Vidal for the left—but ideologues in an educated, patrician, and articulate men-of-letters sort of way. Perhaps they could demonstrate to a mass audience that it was possible for debates between political opponents to employ words that were honest, intellectual, and constructive rather than pejorative, dismissive, and rancorous.

That sort of example was desperately needed in the United States in 1968, a time when people who disagreed with the political ideas of other people had picked up an alarming habit of shooting them or beating them senseless. Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. were assassinated; race riots raged in dozens of cities; and during the Democratic National Convention, anti-Vietnam War protestors fought the Chicago police for control of the city’s streets in an epic eight-day running battle. Buckley and Vidal, then, must have seemed like just the ticket. They were smart and hyper-articulate, and their plummy, East Coast establishment tones made them seem so, well, civilized. Perhaps they could demonstrate a more mature way to deal with political differences. Or not.

In their most famous exchange, on August 27, 1968, Buckley asserted that Vidal was unqualified to say anything at all about politics, calling him “nothing more than a literary producer of perverted Hollywood-minded prose.” Vidal retorted that Buckley “was always to the right, and always in the wrong,” and accused him of imposing his “rather bloodthirsty neuroses on a political campaign.”

After that the gloves came off.

“Shut up a minute,” said Vidal. Buckley did not shut up. Vidal called him a “proto- or crypto-Nazi.” Buckley was not happy with that. “Now listen you queer,” he said. “Stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in the goddam face.”1 Buckley went home in a huff and sued Vidal for libel. Vidal went home in a huff and, perhaps miffed that he didn’t think of it first, counter-sued Buckley for libel.

So much for a civilized exchange of views.

At this point we could cluck our tongues and make highbrow academic noises about the degeneration of political exchange. We could point back to the early days of the American experiment and hold up the dignified Founders as better examples of civil and edifying political debate. We won’t, though, because they, too, stuck in the shiv when it suited them. Like Buckley and Vidal, Alexander Hamilton and John Adams could be insufferable know-it-alls, intolerant of viewpoints other than their own. President Adams signed into law the Alien and Sedition Acts, making it a crime to say nasty things about the government—a good deal if you are head of that government—and Hamilton engaged in a personal feud with Vice President Aaron Burr so vitriolic it ended with Burr putting a musket ball through him. As an example of politics putting people on the boil, it is difficult to top the sitting vice president of the United States shooting and killing one of the prime movers and signatories of the Constitution. Other Founders weren’t much better. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, held up in the United States as semi-divine political angels descended from Mount Independence, chucked mud with the best of them. Jefferson, for example, slandered his opponents on the sly. He bankrolled James Callender, a professional “scandal monger,” to attack Adams. Callender obliged, describing Adams in scorching prose as “a repulsive pedant, a gross hypocrite and unprincipled oppressor.”2 Callender was tossed in jail for violating the Alien and Sedition Act (score one for Adams) and Jefferson got a nasty bit of blowback—he fell out with his journalistic attack dog, who promptly turned to writing titillating tales about Jefferson’s affairs with an attractive slave named Sally Hemmings. Jefferson indignantly and, if you believe DNA testing on Hemmings’ descendants, wholly misleadingly said he did not have sexual relations with that woman.

Don’t be smug if you are not from the United States; we’re willing to bet your political icons are not much different from the feet-of-clay rhetorical flame-throwers blistering each other under the Stars and Stripes. Show us a paragon of politics from any time and place and chances are we won’t have to scratch the surface too hard before finding something like the Buckley-Vidal kerfuffle, in other words someone saying the other guy’s political views are so wrongheaded they merit a fast-moving fist to the schnoz.

People take politics seriously. They love validation of their own opinions and vilification of their opponents’ opinions. This is why conservatives make Ann Coulter, Michelle Malkin, and Mark Levin best-selling authors, Rush Limbaugh a wealthy talk-radio titan, and Fox News the most watched outlet on cable television. These sources can be counted on to tell their audiences that conservatives are noble defenders of the good and the just while liberals are stubbornly mugger-headed and oppositional. Driven by a desire to receive precisely the opposite message, liberals flock to the books of Al Franken, Michael Moore, and Molly Ivins, and the satire of television comedy like The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. Stephen Colbert of The Colbert Report has created a massively successful career around the persona of a shallow, jingoistic, uniformed conservative buffoon. Diatribes against liberals or conservatives enjoy a guaranteed audience of partisans all subscribing to the maxim, “why be informed when you can be affirmed.”3

If we were of an avaricious bent, we could write another broadside against stupid, inbred, uninformed, malodorous, bloodsucking conservatives. If we really wanted the big bucks, we could pen a blistering condemnation of duplicitous, malevolent, degenerate, cretinous liberals. Such works sell very well among certain demographics and, having read a fair sampling of what’s on offer, we see little evidence that it takes much effort or talent to get on a good rant. Authors of these popular political screeds rarely seem to invoke—let alone conduct—systematic research. Ginning up a truckload of demeaning adjectives to unload on one group or another? Sounds like it might be fun as well as profitable. Unfortunately, we are academics, so neither profit nor fun is what interests us most.

Besides that, the world does not need another book assuring readers that their political views are laudably correct while those of their political opponents are pathetically, dangerously, and rashly incorrect. Such books only pander to the worst instincts of those who care deeply about politics, encouraging extremity and discouraging dialogue. Ad hominem attacks on the political “other side” may be comfortingly confirmatory to readers and financially fulfilling to authors, but they are shallow, derivative, and polarizing.

In this book we aim to explain why people experience and interpret the political world so very differently. We want to provide liberals with a better appreciation for the conservative mindset; conservatives with a better appreciation for the liberal mindset; and moderates with a better appreciation for why those closer to the extremes make such a big fuss. We make no pretense that conservatives and liberals can be led to agree on everything, or even anything. Getting the Buckleys and the Vidals of the world to hold hands and sing “Kumbaya” around a campfire is just not going to happen. Pretending that some middle-ground nirvana can be reached if only we listen to the other side is counterproductive and a source of endless frustration. We are after smaller but important and much more realistic game. We want liberals and conservatives to understand why they are different from each other and why those differences frequently seem so unbridgeable.

We recognize what we are up against. Liberals and conservatives are rarely in the mood to understand the other side. This resistance to accepting the other side is something we have encountered in our own professional lives. A few years ago, we published a study showing that liberals and conservatives experience the world differently and suggested that it might be unproductive and slightly inaccurate to view either side as irredeemably malevolent—or unremittingly beneficent. Media coverage of this study led to us to receive numerous emails. Some of these were decidedly caustic, but the most memorable was more plaintive than judgmental. Its key line was “don’t do this to me: I NEED to hate conservatives.” Clearly, for some it is deeply rewarding to denounce political adversaries, preferably at high volume.

Facing Your Monsters

“If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention,” goes the old saying. We disagree. Outrage does not solve challenging issues of governance and it is possible for people to pay close attention to politics without losing emotional control. A more productive, if less viscerally satisfying, response to political difference is to try to understand the source of the views of those who disagree with us so fundamentally. Doing so does not mean your resolve is weakening or that your fellow travelers should begin to worry about you; making an honest effort to understand the other side is not selling out.

In urging each side in the political debate to work harder at accepting the other side, we are not implying that the two poles of the ideological spectrum are mirror images of each other and equally culpable on all matters. The media often engages in “false equivalency,” leaving the impression that if a problem exists, both sides must have contributed equally to its creation. For example, if one side of the political debate is not compromising then the other side must not be compromising either. This is not our position at all. Our pitch is that liberals and conservatives and everyone in between have different orientations to information search and problem solving and therefore contribute to political difficulties and solutions in very different ways. Indeed, one manifestation of this is that the two ideological poles have quite different attitudes toward compromise.

To illustrate the value of entering the mindset of the other side, consider the following. One of our children was given to horrible nightmares. He would cry and shout as monsters circled in his sleep. Words from the awake world (“there is no monster under your bed”) could not disabuse him of the fears that were so real to him. Weeks into this unpleasant pattern, due more to desperation than inspiration, his parents’ strategy changed. Instead of telling him how silly and outrageous he was being, they entered his dream world. “Yes, there is a monster. Oh, he’s an ugly one—mean, too—and he’s coming this way. But wait, he just spotted some monster friends of his and he’s moving off in another direction— way off.” By imagining the world he was in and by letting him know that others understood the nature of that world, it became possible to work through the attending issues. Blissful sleep—for parents and child alike—soon descended where monsters had lurked only moments before.

Dismissing the nightmare world of political adversaries is a wholly ineffective approach to solving political problems. What is lost by making a real effort to enter their world, not with the intention of joining them but to understand the reasons they have come to such different political conclusions? You are free to believe that the world of your political adversaries is as detached from reality as a scared little boy’s nightmare world—but realize it is as real to them as the monsters were to him. Also realize that to your political adversaries, your world is as detached from reality as a child’s green, scaly monster. Maybe if we understand their world we can figure out how to live with people who annoyingly, irritatingly, and persistently come to political viewpoints so very different from our own. Puzzlement is better than hate.

In this book we make the case that political variations are part of an incredible range of differences in the way people respond to the world. Just to give you a brief teaser, it turns out that liberals and conservatives have different tastes not just in politics, but in art, humor, food, life accoutrements, and leisure pursuits; they differ in how they collect information, how they think, and how they view other people and events; they have different neural architecture and display distinct brain waves in certain circumstances; they have different personalities and psychological tendencies; they differ in what their autonomic nervous systems are attuned to; they are aroused by and pay attention to different stimuli; and they might even be different genetically. At least at the far ends of the ideological spectrum, liberals and conservatives are emotionally, preferentially, psychologically, and biologically distinct. This account is not just based on casual observation or armchair analysis. Science—both social and biological—is our co-pilot.

Liberals and conservatives often are reluctant to accept that their differences are rooted in psychology, let alone biology. Their own political beliefs seem so sensible, rational, and correct that they have difficulty believing that other people, if given full information and protected from nefarious and artificial influences, would arrive at different beliefs. Liberals are convinced the existence of conservatives can be written off to Karl Rove’s treachery, the Koch brothers’ fortune, the bromides of Fox News, and a puzzling proclivity to think simplistically. Conservatives are equally convinced the existence of liberals is attributable to the “lamestream” media, indoctrination by socialist university professors, the sway of Hollywood, and a maddening tendency to disengage from the real world. Yet political differences are grounded not in a duplicitous conspiracy or an irrational disregard of logic and truth but rather in variations in our core beings. Conservatives are not duped liberals and liberals are not lazily uninformed conservatives.

You would not come to this conclusion by looking at much of today’s popular political commentary. Egged on by ideologically biased authors and personalities, efforts to understand political opponents often go no further than the assertion that they are ignorant, obdurate, and uninformed—those on the right are “big fat idiots” and those on the left are “pinheads.”4 Accepting that political differences are due not merely to incorrect information, elite machinations, or an unwillingness to think through situations is an important step toward living more comfortably. A better understanding of the biological and psychological realities of our political opponents makes it possible to recognize that their policy preferences, however misguided to our eyes, are sensible given their different realities. Getting to that point is crucial. As journalist Robert Haston put it, “[W]e can accept and understand the red or blue tribal instincts that drive the other half, or we can continue our retreat into ever more blind and vicious combat.”5

Nobody’s Perfect, but We’re Working on It

We are often asked why we research the deeper bases of political differences and invariably our questioners assume that the real goal must be to paint one political group or another in an unfavorable light. We must be a bunch of academic lefties trying to stick it to the right. Or maybe we are traitors to the cause and are out to disparage the left. The notion that social scientists might be studying the nature of the human condition without promoting an alternative agenda is rarely accepted, particularly when the topic is politics.

The central message of this book is that lurking predispositions are widespread, so we would be the last people to claim social scientists or anyone else can be 100 percent objective and value free. If you think you are not biased, you are fooling yourself. You get an exception only if you have pointy ears, green blood, and a commission from Star Fleet. While we are just as biased as everyone else, the great thing about the scientific process is that the biases of a single research team eventually get squeezed out. In our bailiwick, data and evidence ultimately rule, or at a minimum have more influence than hidden political agendas. Our world is the world of empirical social science, a pretty ruthlessly Darwinian piece of real estate. It revolves around an ongoing scientific process that affords skeptics the chance to participate fully. Different researchers weigh in, replication will occur (or not), and eventually the truth will emerge—not a definitive or ultimate truth but the best current shot at the (relatively) unbiased truth. You should be on guard for suspect methods and biased inference but you should not be paralyzed by suspicion. You should be skeptical of the results of a single study, including anything we have published. Yet if numerous studies conducted by numerous labs with alternative techniques and in diverse settings begin to point in the same direction, you should accept that the burden of proof shifts to those who deny that liberals and conservatives have deep differences.

Unfortunately, when it comes to politics, the distinction between systematic, validated description and howling ridicule is all too often ignored, the upshot being that any research showing psychological or biological differences between liberals and conservatives is reflexively treated by one side or the other, and often both, as biased. To take one example, evidence that conservatives are more conscientious while liberals are more tolerant of uncertainty is thought to be less an effort to understand political temperament than an attempt to belittle liberals/conservatives (take your pick) while hiding behind the veneer of science. When it comes to ideology, difference equals value judgment in the minds of many, when in reality it is possible to be different without being better or worse.

That said, we freely recognize that suspicions of political judgments hiding within social science research (or even in the headlines) are not without foundation. One piece of early research on the deeper bases of political attitudes concludes that conservatism is characteristic of “social isolates, of people who think poorly of themselves, who suffer personal disgruntlement and frustration, who are submissive, timid and wanting in confidence, who lack a clear sense of direction and purpose, who are uncertain about their values, and who are generally bewildered by the alarming task of having to thread their way through a society which seems to them too complex to fathom.”6 More recent research describes conservatives as “easily victimized, easily offended, indecisive, fearful, rigid, inhibited, relatively over-controlled, and vulnerable.”7 It is a wonder conservatives can get themselves out of bed in the morning.

Were these conclusions unduly biased? We can say that the two studies cited above were quickly and robustly challenged. Like others who deconstructed the empirical and conceptual case behind those statements, we are skeptical of some of the supporting evidence. That is what the scientific process does. Identifying problems makes it possible to correct them subsequently. The account we present in this book is based not on a single study but on a massive collection of studies conducted by many scholars in many countries. This does not mean the final truth has been discovered; it means that the weight of evidence permits confidence in the claim that liberals and conservatives really are fundamentally different.

We are not trying to demonstrate that conservatives are crypto-Nazis or that liberals are naïfs who need a good sock in the mouth to jar them into recognizing reality. We just want to know why people are so different politically. So, if only for the time it takes to read this book, we ask readers to suspend any instincts to dismiss as crassly biased any research that does not conclude that their political foes are evil incarnate. We will note some imperfections of those foes along the way, but keep in mind that nobody is perfect and the imperfections of liberals are very different from the imperfections of conservatives. The task we set ourselves here is not to tally the imperfections of each ideological group in order to declare one group the winner. We just want to know why the groups exist in the first place.

Whether the topic is climate change, evolution, genetically modified foods, or the biological basis of political beliefs, people are quick these days to apply the label of junk science to research on controversial matters. The implication is that some research is driven by special interests and hidden agendas to such an extent that it cannot be considered real science or, more likely, that some topics are simply not suitable for science. Replication should take care of the hidden agenda issue and as far as some topics not being amenable to the scientific process, consider this. Researchers recently presented one group of people with scientific evidence that confirmed their prior beliefs while a second group received the same evidence but it disconfirmed their prior beliefs. Compared to those receiving belief-confirming evidence, those receiving the belief-disconfirming (but very same) scientific evidence were much more likely to conclude that the topic could not be studied scientifically.8 In other words, the charge of junk science appears to be nothing more than a lazy way of saying “I don’t like the findings.”

What about Me? I’m a Libercontrarian

What about those who do not feel comfortable being pigeonholed as liberal or conservative? What about all those folks who live in countries where those two words do not hold much meaning, even when translated? What about all the people who could not care less about politics? A common mistake in addressing differences in political orientations is to leave the impression that they begin and end with the distinction between liberals and conservatives or between those on the political leftand those on the right (we use these pairs of terms interchangeably). These labels are short, convenient, and convey an intuitive notion of political differences. We will use them for exactly that reason throughout this book. Still, it is quite true that they fail to capture the political views of a goodly percentage of people. So before going any further we wish to make it clear that, even though we often use phrases such as liberal and conservative or leftand right for shorthand, this book is about political differences generally and not merely differences between two discrete collections of ideological beliefs.

The differences we are talking about reflect variation across a continuum and perhaps many continuums, not traits that lump everyone into two camps. When we say left/right or liberal/conservative, what we have in mind is more a yardstick than two measuring cups. Some scholars think ideology is such a complicated and nuanced critter that it demands more than one type of measurement—sort of like body mass is measured by height and weight, ideology should be measured by, say, views on economic policies and views on social policies. Even so, the unidimensional concept of making sense of political differences captures a very long tradition of describing political differences.

Plato (liberal) and Protagonus (conservative) are sometimes viewed as the progenitors of these political types, though undoubtedly prehistory is chock full of earlier illustrations; Catherine the Great’s Russia, for example, was fraught with conflicts over abolishing serfdom, the role of religious freedom, efforts to rein in the nobles, and appropriate attitudes toward the new ideas of the Enlightenment. Nineteenth-century philosopher John Stuart Mill called it “commonplace” to have “a party of order or stability and a party of progress or reform.”9 Ralph Waldo Emerson noted that “the two parties which divide the state, the party of conservatism and that of innovation, are very old, and have disputed the possession of the world ever since it was made.” Emerson called this division “primal” and argued that “such an irreconcilable antagonism, of course, must have a correspondent depth of seat in the human condition.”10 That pretty much sums up what we are interested in doing—looking into the depth of the human condition to figure out the irreconcilable antagonism between political beliefs. Capturing that irreconcilable antagonism by distinguishing between competing sets of preferences labeled conservative/right or liberal/left does not do justice to the full range of political preferences people hold, but this distinction has proven a robust way of categorizing the political divisions present in virtually all politically free countries.11 If it was good enough for Mill and Emerson, it is good enough for us; we’ll explain exactly why in the next chapter.

Using these labels, though, could create confusion, and we want to head that off if we can. For example, in some countries a “liberal” refers to a libertarian, a set of political beliefs generally associated with the conservative end of the political spectrum. As a result, in Australia political conservatives belong to the Liberal Party, which may seem a contradiction. In America the best-known libertarians (e.g., Ron Paul) are found in the Republican Party, which champions the distinctly nonlibertarian policies of government involvement in people’s social lives (for example, preventing women from having abortions and gay people from marrying the spouse of their choice) and massive levels of spending on defense. Instead of using phrases such as liberal and conservative we could more accurately capture political differences by talking about individual preferences that reflect, for example, a desire for security/protection, a desire for predictability/order/certainty, a desire for equality, or a desire for novel structures and events. This approach would provide some useful flexibility and clarify some of the translation issues that can come with left/right or conservative/liberal labels; unfortunately, it also is incredibly cumbersome. So for ease of communication we will stick with “liberal” and “conservative.” We want to make clear, though, that the deeper forces we explore do not demand that there be just two categories of political person. If looked at carefully enough, pretty much everyone’s politics are as unique as their physiologies and cognitive tendencies.12

Indeed, this potential to account for numerous, diverse political orientations means our story is not just about two political camps in the United States. Our claims apply to other countries and other times. If Mill and Emerson are as correct as we believe them to be, a broad left-right dimension anchors politics universally, even if unique issues and varying collections of positions provide plenty of variation. In sum, our results and interpretations apply to those in the United States who are not comfortable categorizing themselves as either liberals or conservatives and also to those living in countries in which the liberal-conservative distinction is not used. People who are moderates (and there are a good many moderates), libertarians, or Social Democrats are likely to have their own politically relevant predispositions.

Fat Men Can’t Jump: Thinking Probabilistically

Accounting for variation in political attitudes is not easy, so if you want to keep that prefrontal cortex in neutral you’re in the wrong book; bail now and pick up a copy of Kenny Conservative’s Liberals Blow or Linda Liberal’s Conservatives Suck a few shelves down. The social world is messy and full of idiosyncrasies, and making sense of what explains variation in political outlook is going to be a hunt for hints in the gray, not the black and white. Social scientists have no equivalents to the law of gravity or E = MC2. We spend most of our time hunting for modest patterns buried amid remarkable complexity. That is the world we are inviting you into.

Many are skeptical of this world, and not without reason. Whenever a study claims to find something that systematically varies with political orientations, lots of people start thinking of exceptions. For example, at least in the United States, more education is generally associated with more liberal-leaning political preferences. Yet it is easy to cite examples of highly educated conservatives (William Buckley was a Yale alum and conservative columnist George Will has degrees from Oxford and Princeton). Higher levels of religiosity are generally associated with being conservative. Yet there are plenty of pious liberals wandering about (Reinhold Niebuhr—one of the best known twentieth-century theologians—was a committed Christian and also an influential left-winger). These contrary cases, though, should be kept in perspective. The occasional exception does not negate a pattern. If it is cold today, that does not mean the global climate is cooling. Knowing a lifelong smoker who still runs marathons does not alter the fact that smoking is a serious health risk. Thinking probabilistically rather than deterministically is absolutely key to understanding the message of this book.

All the relationships we describe are only tendencies, not hard and fast rules. Predispositions are not destiny, but defaults—defaults that can be and frequently are overridden. There’s a reason the title of this book is Predisposed and not Fated. But the fact that there is any predisposition at all is important as it tilts subsequent attitudes and behavior in one direction or the other. A person with a particular set of physiological and cognitive traits will not automatically be a liberal or a conservative, but is more likely to be one or the other.

With regard to our approach in this book, we’d like to put our cards on the table. We have a pair of nines. A reasonable hand for five-card stud but not a sure-fire winner. We may not be doing ourselves any favors by confessing that we cannot claim to have discovered the definitive basis of political differences. Nobody likes caveats hanging from their bumper sticker certainties. But we think that much of the skepticism surrounding this line of research stems from people perceiving that the results and claims are stronger than they are. Critics of research on political predispositions are eager to create a straw man by arguing that proponents are making powerful assertions such as “people’s political orientations are hardwired from birth” even though those doing the research recoil from those sorts of deterministic pronouncements.

So, as you ponder the message of this book, we ask that you banish “determine” from your vocabulary and replace it with words such as “shape,” “influence,” “mold,” and “incline,” and that you be ready for violations of any rule proffered. This is important because, particularly when biological variables are involved, some people tend to think one exception to the claimed pattern negates the entire enterprise. This simply is not the case; biology (and certainly psychology) largely works probabilistically rather than deterministically so exceptions are always to be expected. Eating lots of junk food, for example, increases your chances of suffering from a whole range of health problems. It does not guarantee those problems will actually appear—some candy-snacking fast food devotees stay in good health, the lucky so-and-sos—but it does make it a lot more likely.

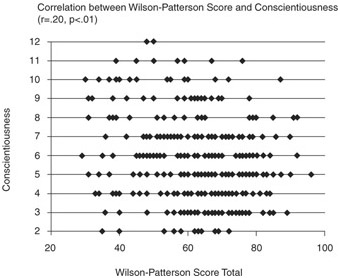

To get accustomed to thinking probabilistically, we need a good, simple example. Consider the relationship between a personality trait—for example, conscientiousness—and ideology. Higher levels of conscientiousness correlate with being more conservative, a relationship replicated in a number of independent studies. Fair enough, but what exactly does being “correlated” mean, and how can we vest any confidence that this relationship is real? To begin, we need reliable measures of both conservatism and conscientiousness. Though we can observe indicators of conservatism (say, who you vote for) or conscientiousness (say, whether or not you jaywalk), these are mostly psychological concepts. How conservative or conscientious we are is something that exists mostly in our heads, making measurement challenging. We lack a skull-penetrating measurement machine that tells us how long your conservatism is in millicons or what your conscientiousness weighs in consc-o-grams. Social scientists overcome this problem mostly by asking people how conservative and how conscientious they are.13

Luckily for present purposes, one of our data sets—taken from a sample of about 340 American adults in the summer of 2010—has a measure of conservatism as well as a measure of personality traits, including a measure of conscientiousness. If we divide our sample into conservatives and liberals and those who are and are not conscientious, we get the distribution displayed in the table in the top panel of Figure 1.1. This shows that 52 percent of conservatives are conscientious compared to 40 percent of liberals. If we reach into this distribution and randomly collar one of our conservative research subjects, our best bet is that he or she will be conscientious. Randomly selecting a liberal, on the other hand, would yield someone conscientious only an estimated 40 percent of the time. There is no certainty to this outcome—only a set of odds that make the conservative research subject marginally more likely to be conscientious and the liberal research subject marginally less likely to be conscientious. In casino terms, a conscientious conservative is the safe bet—and while it will not always pay off, over the long run it will. This general description applies to most all relationships in the social and biological sciences. Certainty is rarely apparent; get used to exceptions.

Though getting across the basic notion of probabilistic relationships, frequency comparisons are pretty crude and uninformative. For one thing, we just completely ignored the main point of the previous section; people’s

political beliefs do not fit neatly into two distinct boxes, but range across an infinite set of possibilities between the right and left. It is the same deal with conscientiousness—differences with regard to this trait are generally of degree rather than kind. A more accurate approach to assessing these sorts of relationships is through the statistical concept of correlation, which makes it possible to look at measures that have many increments, not just two.

Take a look at the graph in the second panel of Figure 1.1, the one that looks like somebody let fly with both barrels of a shotgun into a barn door. This contains the same information as the table in the top panel. The difference is that the picture—known as a scatterplot—includes all the variation in our measures rather than divvying it up into four liberal/conservative and conscientious/not conscientious boxes. Our measure of conservatism was not a simple are-you-or-aren’t-you question. We asked people their opinions—whether they strongly agreed, agreed, disagreed, or strongly disagreed—with 20 issue positions on everything from defense spending to gay marriage.

We converted conservative positions (e.g., strongly disagreeing with gay marriage, strongly agreeing with school prayer) into higher numbers then added together all the scores. This gives us a potential range of 20 (very liberal on all issues) to 100 (very conservative on all issues) with a full range of intermediate positions in between. The liberal/conservative items constitute what is known as a Wilson-Patterson index of conservatism, a set of questions that captures left-right political differences on a wide range of issues, making it possible to measure political orientations as a range rather than just as a category. For conscientiousness we used two questions from a standard “Big Five” test of personality traits. These items asked people the extent to which they saw themselves as “disorderly and careless” and how accurately they felt the statement “I can’t relax until I have everything done that I planned to do that day” described them. Responses to the first question ranged from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (7); responses to the second ranged from very accurate (1) to very inaccurate (5). Adding these together gives an index with a theoretical range of 2 to 12, with those scoring higher being presumably more orderly, careful, and committed to finishing their to do list every day. In other words, people who are more conscientious.

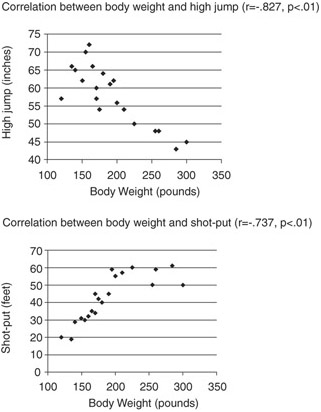

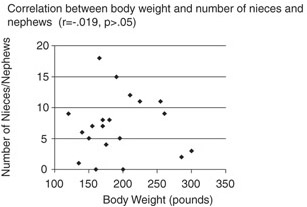

Great. We computed two measures, plotted them on a standard X-Y axis graph and ended up with something that looks like an aerial shot of Trafalgar Square after a particularly nasty outbreak of pigeon diarrhea. What good does that do us? The answer might be made a little clearer by looking at the scatter-plots in Figure 1.2. These plot body weight first with high jump performance (top panel), then shot put performance (middle panel), and then number of nephews and nieces (bottom panel), for 20 hypothetical male athletes. The top two panels show clear relationships; the bottom panel doesn’t show any relationship at all. That is about as far as “eyeballing” the data can get you. What about statistics?

All of these visual relationships can be assessed more systematically by something called a coefficient of correlation (often referred to as an r), a computation

Figure 1.2 Illustration of Negative, Positive, and No Relationship

that spits out a number between −1 and +1 summarizing the extent to which two variables are related to each other. A negative relationship indicates that as one variable goes up, the other goes down. The correlation for the two variables in the top panel is −0.83—in other words, the more you weigh the lower your ability to launch yourself any considerable distance from the ground. The correlation for the two variables in the middle panel is 0.74—in other words, bigger guys can chuck cannonballs farther. These are really high correlations and they also make sense. It is difficult to imagine sumo wrestlers Fosbury Flopping over six feet, just as it is difficult to imagine top-flight marathon runners heaving 16-pound lead balls 60 feet. The correlation in the bottom panel is near zero—0.02 to be exact—indicating no relationship between these variables. That, too, makes sense. As far we are aware, your heft has little to do with the reproductive capacities of your siblings.

So we have a handy number that can summarize some obvious relationships between body weight and just about any other variable you care to imagine. What exactly does this have to do with politics? Look back at that bottom panel of Figure 1.1. While it is hard to discern a clear relationship, one does exist. There is a correlation of +0.20 between conservatism and conscientiousness. What this means is that the higher your score on conservative issue positions, the higher your score on the conscientiousness index. This, though, is a pretty small correlation. A correlation of 0.20 means conscientiousness is positively related to conservatism, but there is a good deal of “slop”—in other words, plenty of conscientious people are liberal and plenty of not so conscientious people are conservatives. On the basis of the evidence, we cannot say that all conservatives are conscientious—we would need a correlation of 1.0 to do so, and we are clearly some distance from that territory. Technically, we cannot even say that conscientiousness causes conservatism or vice versa—conservatism and conscientiousness might both be caused by something else. What we can say is that there is a modest but systematic tendency for conscientious people to be conservative. That might not be completely obvious from the scatterplot in Figure 1.1, but it is there.

You might notice that underneath each figure reference is not just an r but also a p value. P here stands for probability and should be interpreted as the likelihood of a relationship occurring by chance. A low p increases confidence in a relationship. Scholarly norms hold that the p should be less than 0.05 (less than one chance in 20 that the relationship occurred by chance), as is the case for the conscientious-conservative connection, for the relationship to be considered meaningful or “statistically significant.” So, to vastly oversimplify, in evaluating relationships, look for big r values and low p values.

A correlation coefficient of 0.20 may seem limp and anticlimactic but in the world of social behavior, coefficients of 0.20 or even 0.10 are often met with great excitement, especially when they are replicated by other researchers. For example, traits or behaviors that demonstrate statistically significant correlations with a serious health issue, say breast cancer, of even .1 are viewed as quite important. Ultimately, this is the reason we have taken a statistical digression in the first chapter of the book and run the risk of sending you fleeing back into the comforting polemics of Kenny Conservative or Linda Liberal. The vast majority of the relationships we are going to describe in this book can be summarized by similarly modest correlations. If you think you are an exception to one of the correlations reported in these pages, you are probably right and undoubtedly have a good deal of company. This does not mean those relationships are any less real, though, as long as you remember to think probabilistically. Just as one cold day does not falsify global warming, one conscientious liberal does not alter the fact that there is a systematic relationship between conservatism and conscientiousness.

Leibniz’s Baloney: What Is a Predisposition?

Looking at a pencil is not exactly a thrill-a-minute proposition, but what happens inside your body during this mundane event is a slick piece of biochemical engineering. The eye treats the shape and color of the object as input that is transmitted via the optic nerve to the occipital lobe at the back of the brain where it is then relayed to other parts of the brain and identified as a pencil. What doesn’t happen is also interesting. Though your neurobiology is involved, viewing the pencil likely does not stir up much activity in the limbic or emotional parts of your brain. Looking at pencils, in other words, does not typically give people joy, melancholy, or a case of the hots. The limbic system simply can’t be bothered to get out of bed to pay a pencil much mind. People know this—if you show them a pencil and ask the degree of emotional intensity felt, people’s typical answer is “very little.” This lack of interest can also be measured biologically; physiological changes recorded while a pencil is being viewed tend to be minimal or nonexistent.

Other objects and concepts are not like pencils and stir the brain’s emotional parts from slumber. Loved ones, dangerous animals, beautiful landscapes, disgusting objects, cute babies, and threatening situations all tend to spur activity in neural channels not activated by viewing a pencil. In response to such stimuli, people report intense reactions and exhibit physiological changes. Brain imaging will show heightened activity in emotionally relevant parts of the brain, including the amygdala, insular cortex, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and anterior cingulate cortex; an endocrinological assay will show alterations in hormonal levels; heart rate and respiration will accelerate, pupils will dilate, and palms will get sweaty. To put it more simply, the body changes in measurable ways.

These physiological changes affect how an object is perceived, processed, and responded to—and the variation from person to person in the nature of these responses is substantial. Each of us is primed to respond physiologically and psychologically to certain categories of stimuli—just not to the same stimuli and not to the same degree. Show a group of people the same stimulus and some will flatline while others will get a case of the vapors. These standing, biologically instantiated response orientations are a key part of what we mean when we say “predispositions.” In sum, people are characterized by biological and psychological response tendencies, patterns that can be overridden but that serve as important shapers of behavior.

People are not fully conscious of their predispositions. Gottfried Leibniz, a seventeeth-century mathematician and scientist, called them “appetitions” and argued that, though unconscious, appetitions drive human actions. His ideas so troubled Descartes-addled Enlightenment minds that they were not published until well after Leibniz’s death. Even then, they were not taken seriously for a long time. Recent science, though, is fully on board with Leibniz’s ideas and is providing ever-increasing evidence that people grossly overestimate the role in their decisions of rational, conscious thought, just as they grossly overestimate the extent to which sensory input is objective.

Neuroscientist David Eagleman goes so far as to claim that “the brain is properly thought of as a mostly closed system that runs on its own internally generated activity … internal data is not generated by external sensory data but merely modulated by it.”14 Noting that people often do things because of forces of which they are not aware and then produce a bogus reason for these actions after the fact, Stephen Pinker refers to the portion of the brain involved in constructing this post hoc narrative as the “baloney generator.”15 The baloney generator is so effective that people believe they know the reasons for their actions and beliefs even when these reasons are inaccurate and patently untrue.16

Need examples of physiology affecting attitudes and behavior, even when people think they are being rational? Consider this: Job applicant resumes reviewed on heavy clipboards are judged more worthy than identical resumes on lighter clipboards; holding a warm or hot drink can influence whether opinions of other people are positive or negative; when people reach out to pick up an orange while smelling strawberries they unwittingly spread their fingers less widely—as if they were picking up a strawberry rather than an orange.17 People sitting in a messy, smelly room tend to make harsher moral judgments than those who are in a neutral room; disgusting ambient odors also increase expressed dislike of gay men.18 Judges’ sentencing practices are measurably more lenient when they are fresh and haven’t just dealt with a string of prior cases.19 Sitting on a hard, uncomfortable chair leads people to be less flexible in their stances than if they are seated on a soft, comfortable chair, and people reminded of physical cleansing, perhaps by being located near a hand sanitizer, are more likely to render stern judgments than those who were not given such a reminder.20 People even can be made to change their moral judgments as a result of hypnotic suggestion.21

In all these cases the baloney generator can produce a convincing case that the pertinent decision was made on the merits rather than as a result of irrelevant factors. People actively deny that a chunky clipboard has anything to do with their assessment of job applicants or that a funky odor has anything to do with their moral judgments. Judges certainly refuse to believe that the length of time since their last break has anything to do with their sentencing decisions; after all, they are meting out objective justice. Leibniz was right, though, and the baloney generator is full of it. The way we respond—biologically, physiologically, and in many cases unwittingly—to our environments influences attitudes and behavior. People much prefer to believe, however, that their decisions and opinions are rational rather than rationalized.

This desire to believe we are rational is certainly in effect when it comes to politics, where an unwillingness to acknowledge the role of extraneous forces of which we may not even be aware is especially strong. Many pretend that politics is a product of citizens taking their civic obligations seriously, sifting through political messages and information, and then carefully and deliberately considering the candidates and issue positions before making a consciously informed decision. Doubtful. In truth, people’s political judgments are affected by all kinds of factors they assume to be wholly irrelevant.

Compared to people (not just judges) with full stomachs, those who have not eaten for several hours are more sympathetic to the plight of welfare recipients.22 Americans whose polling place happens to be a church are more likely to vote for right-of-center candidates and ideas than those whose polling place is a public school.23 People are more likely to accept the realities of global warming if their air conditioning is broken.24 Italians insisting they were neutral in the lead-up to a referendum on expanding a U.S. military base, but who implicitly associated pictures of the base with negative terms, were more likely to vote against the referendum; in other words, people who genuinely believed themselves to be undecided were not.25 People shown a cartoon happy face for just a few milliseconds (too quick to register consciously) list fewer arguments against immigration than those individuals who were shown a frowning cartoon face.26 Political views are influenced not only by forces believed to be irrelevant but by forces that have not entered into conscious awareness. People think they know the reasons they vote for the candidates they do or espouse particular political positions or beliefs, but there is at least a slice of baloney in that thinking.

Responses to political stimuli are animated by emotional and not always conscious bodily processes. Political scientist Milt Lodge studies “hot cognition” or “automaticity.” His research shows that people tag familiar objects and concepts with an emotional response and that political stimuli such as a picture of Sarah Palin or the word “Obamacare” are particularly likely to generate emotional or affective (and therefore physiologically detectable) responses. In fact, Lodge and his colleague Charles Taber claim that “all political leaders, groups, issues, symbols, and ideas previously thought about and evaluated in the past become affectively charged—positively or negatively.”27 Responses to a range of individual concepts and objects frequently become integrated in a network that can be thought of as the tangible manifestation of a broader political ideology.

The fact that extraneous forces that may not have crossed the threshold of awareness (sometimes called sub-threshold) shape political orientations and actions makes it possible for individual variation in nonpolitical variables to affect politics. If hotter ambient temperatures in a room increase acceptance of global warming, maybe people whose internal thermostats incline them to feeling hot are also more likely to be accepting of global warming. Likewise, sensitivity to clutter and disorder, to smell, to disgust, and to threats becomes potentially relevant to political views. Since elements of these sensitivities often are outside of conscious awareness, it becomes possible that political views are shaped by psychological and physiological patterns.

It is important to recognize that predispositions are not fixed at birth. We cannot emphasize enough that we are not making a nature versus nurture argument. Innate forces combine with early development and later powerful environmental events to create attitudinal and behavioral tendencies. These predispositions are physically grounded in the circuitry of the nervous system, so once instantiated they can be very difficult, but far from impossible, to change. Altering a predisposition is like turning a supertanker; it usually takes concerted force for an extended period of time, but it can be done. Just like those heavy clipboards, a variety of predispositions nudge us in one direction or another, often without our knowledge, increasing the odds that we will behave in a certain way but leaving plenty of room for predispositions to be contravened and also for the predispositions themselves to be modified.

Still, while it is possible for situations and events to alter predispositions, attitudes are notoriously resistant to change. This is true outside the realm of politics and definitely true within it.28 An individual’s political orientation follows a pattern similar to that identified for happiness. Psychologists frequently refer to a “happiness set point.” Events throughout a lifetime make people happier or sadder for a time but most individuals are generally oriented toward being upbeat or not and the effects of various events typically lead to modest and temporary deviations from the set point. Several months after experiencing even major life events such as an amputation or winning the lottery it appears that most people have returned to a degree of happiness with their lives surprisingly similar to that present before the major event.29

Politically relevant predispositions are similar: malleable but also resistant to change. This conclusion squares with a growing body of evidence documenting the long-term stability of people’s political orientations.30 Most people know someone who has done a political 180-degree turn, but these individuals stand out because they are relatively rare and do not pose a challenge to the core idea of predispositions as physically instantiated inclinations (remember, think probabilistically). We believe the reason for this relative stability is the existence of an ingrained emotional and therefore physiological response to stimuli that ends up being relevant to politics. It takes quite a bit for such habituated emotional responses to be eliminated, let alone reversed. Once they are there, they tend to be there for the long haul. As one study concludes, “[W]hen it comes to politics you’ve either got it or you don’t.”31

Predispositions, then, can be thought of as biologically and psychologically instantiated defaults that, absent new information or conscious overriding, govern response to given stimuli. For example, people may have a predisposed response to Barack Obama that would be evoked by a garden-variety image of him. Subsequent events and information, perhaps about his role in killing Osama Bin Laden, or a picture of him losing his composure, could alter that default response. The question is whether the new information becomes a long-term component of (adjusted) predispositions or whether, say, an existing negative predisposition toward Barack Obama would soon neutralize the positivity that might have been generated by the successful attack on Bin Laden’s compound, rendering the new information irrelevant to evaluations.

A final critical and often misunderstood element of predispositions is that they are not equally present in all people. Just as the content of the predisposition varies from person to person, so too does the degree to which a predisposition is present at all. Being politically predisposed is not a requirement for membership in the human race. Like most everything else, the presence of predispositions should be thought of as operating along a continuum. Certain people are in possession of powerful political predispositions and politically relevant stimuli set off easily measurable psychological, cognitive, and physiological responses. Perhaps the nature of the political predisposition points in a liberal direction, perhaps in a conservative direction, or perhaps in different directions depending upon the particular issue. Other people have much weaker political predispositions. For them, politics is mostly irrelevant and they do not have much in the way of a preexisting, physiocognitive basis for their political behavior and attitudes. These individuals are often puzzled by all the fuss about politics.

The central thesis of this book is that many people have broad predispositions relevant to their behaviors and inclinations in the realm of politics. These predispositions can be measured with psychologically oriented survey items, with cognitive tests that do not rely on self-reports, with brain imaging, or with traditional physiological and endocrinological indicators. Due to perceptual, psychological, processing, and physiological differences, liberals and conservatives, for all intents and purposes, perceive and thus experience different worlds. Given this, it is not surprising to find they approach politics as though they were somewhat distinct species.

“We Have Known That All the Time!” But “It Can’t Be True!”

These claims create controversy inside and outside academia but also seem intuitive. Folk wisdom has long put down political differences to something deep, perhaps even biological. Groucho Marx famously remarked that “all people are born alike—except Republicans and Democrats.” In their comic opera “Iolanthe,” Gilbert and Sullivan wrote that “every boy and every gal that’s born into the world alive, is either a little liberal or else a little conservative.” Enduring political differences are endless grist to the mill of humorous one-liners: Democrats eat their fish, Republicans hang theirs on the wall; Democrats make plans and do something else, Republicans follow the plans their grandparents made; Republicans tend to keep their shades drawn although there is seldom any reason why they should, Democrats ought to but don’t.32

Folk wisdom may recognize the deep, nonpolitical differences separating liberals from conservatives but academic wisdom is not so sure. There have been numerous efforts to study whether political beliefs reflect deeper psychological tendencies such as personality traits (we address this possibility in Chapter 4). These attempts have frequently been met with scorched earth criticism. In the 1950s Theodor Adorno’s book on the authoritarian personality was derided as “the most deeply flawed work of prominence in political psychology,” the “Edsel of social science research,” and one of the most harmful books in centuries.33 In the 1960s, Silvan Tomkins’ theories of biologically based emotions and their potential links to political temperament were subject to vigorous counterattacks.34 In the 1960s and 1970s when Glenn Wilson and John Patterson developed a general instrument of social conservatism and argued it represented an underlying personality trait that was possibly heritable,35 they were immediately challenged.36 Comedians, songwriters, and the lay public have long taken for granted that politics runs deep and connects to other facets of life, but historically many in the academic community have been unwilling to concede this point.

This situation may finally be changing. After a lull, the last 10 years have seen a flowering of research on the broader forces intertwined with politics. This more recent research can be placed in one of two overarching categories. In the first, politics is measured using survey questionnaires that probe characteristics like personal values, moral foundations, personality traits, psychological tendencies, and sensitivity to disgust.37 In the second, students of political orientations employ a whole array of cognitive and biological tests, including eyetracking, gaze cuing, brain imaging, genetics, electrodermal activity, and electromyography (facial muscle movements). These techniques make it possible to acknowledge the important role of factors that may not enter people’s conscious awareness.

Survey-type self-reports are important parts of the measurement arsenal but sometimes people’s baloney generators get in the way and leave them incapable of reporting how they feel and why they did what they did. The predispositions people bring with them into political situations can be referred to as motivated social reasoning, hot cognition, habits, longstanding predispositions, or antecedent conditions.38 Regardless of the label, the nature of these predispositions is in part unavailable to the people holding them; as a result, techniques other than survey self-reports are essential and form a central element of our story. Even readers primed to accept that the differences between liberals and conservatives extend well beyond the realm of politics may not appreciate the biological and cognitive depth of these differences.

In short, for the first time real progress is being made in connecting political variations with biological and cognitive variations. This newer, biologically informed research is cumulating in a fashion that the more psychologically based efforts of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s did not, but the critics of placing politics in broader context have not gone away. In fact, for several reasons, they appear more tenacious. The incorporation of biology is particularly troubling to people who fail to realize that biology is not tantamount to determinism. Many scholars believe the only way to understand political orientations is “by understanding history and culture.” They believe the notion that biologically instantiated predispositions have a universal application to politics regardless of time and space is “implausible” or even “incoherent.”39 We assert instead that history and culture have helped to shape biologically instantiated predispositions that then take on a life of their own and need to be studied alongside history and culture.

Moreover, the popular press monitors academic findings in this area closely, opening channels to a broader array of critics. Online outlets and networks further widen opportunities to offer commentary, particularly on an incendiary topic such as the deeper differences between liberals and conservatives. Whereas critics of the earlier iterations often were restricted to academic circles, that is hardly an apt description of the current situation. George Will assailed psychologist John Jost for his assertion that political orientations are undergirded by motivated social cognition. Will apparently took umbrage at the notion that people are merely led around by their “dispositions.”40

For their part, bloggers claim that political choices are made “according to what is good and evil” and they often challenge the evidence documenting the importance of predispositions. They insist that political beliefs are fully under an individual’s control, meaning that people who hold “terrible” beliefs can be expected to “come around eventually,” though such a belief is more wishful thinking than factual. Whether the worry is that the existence of deeper, biological, politically relevant predispositions will impugn people’s preferred political ideology or, more generally, that it will call into question the ability of humans to be politically rational and decent, denial of the existence of politically relevant predispositions is common.

Though critics of the movement to place politics in biological and psychological context hail from academia, journalism, and the public at large, political scientists are especially dubious. A longstanding assumption in political science, best exemplified in the influential work of Philip Converse, is that political beliefs and ideologies are narrow and apply only to politics. The fundamental idea is that to be in possession of a political ideology it is necessary to know the meaning of labels such as liberal and conservative and also to be in possession of a consistent set of political preferences that add up to a coherent match with those labels. The notion that people’s politics bubble up from their broader, inner machinery is absent from the Converse view and therefore from much of traditional political science. As a result of this formulation, many scholars have convinced themselves that ideology is rare and getting rarer now that the big isms, such as Communism and Fascism, are history.41 The gist is that, at least politically, people now are all the same, residing in a motley middle where they are undisturbed by the flow of big ideas and very disturbed by the ideological bent of elite politicians.42 Only the elites have ideologies, we are told, and claims that politics is an extension of each individual’s unique and generic psychological, cognitive, and physiological forces are treated with a heavy dose of skepticism (which we don’t mind) and even derision and contempt (which we do).

In sum, Groucho Marx, Gilbert and Sullivan, and folk wisdom notwithstanding, plenty of people find the possibility of deeper, biological bases of politics both unbelievable and off-putting. Journalist and author Chris Mooney captures the situation when he describes the assertion that liberals and conservatives are different sorts of people as “something we’ve always sort of known but never really been willing to admit.”43 Our own research has been dismissed as inconsistent with realistic beliefs about humans and politics and simultaneously written off as something that “we already know,” even though we’re not sure how it’s possible to be guilty of both sins at once. Our goal in this book is to show readers that deep, biological, politically relevant predispositions are quite real and anything but preposterous.

Conclusion: Why Can’t We All Just Get Along?

Though seductive, the vision of a political rapprochement in which individuals from all corners of the polity converge in the political middle as they sing “Kumbaya” is a dangerous fantasy. Even if such a group-sing came to pass, liberals probably would be holding their lighters aloft, swaying as they sang with undisciplined abandon, while conservatives would be sitting in orderly rows, perhaps pews, performing a clipped, somewhat cold, but extremely well-rehearsed rendition. The forced agreement on lyrics and melody would be superficial and misleading. Vidal would be in the back making up dirty lyrics and Buckley would be down front trying to maintain order and threatening to punch Vidal in the kisser. The way to live with political differences is not to perpetuate the myth that they are a passing and remediable inconvenience but to recognize their depth and work effectively within the constraints they inevitably create. Rather than fanning the flames of ideological disagreement, the goal should be to ameliorate the problems disagreement creates.

Acknowledging the real nature of people’s political differences could allow strategies for campaigns and for the presentation of governmental policies to be more fine tuned, targeted, and effective; policies themselves could be more legitimate as a result, thereby facilitating compliance; casual political discourse could also become more constructive and, perhaps most importantly, understanding and tolerance of those who disagree with us politically could be enhanced, rendering the entire political arena a less frustrating place. Understanding the reasons for gridlock and polarization will not cause these problems to disappear magically but will suggest realistic approaches to softening their edges and improving governance. In Chapter 9, we will describe in more detail how all this might work.

Such an acknowledgment would not entail giving up on efforts at political persuasion. Remember that the relationships we are about to describe are modest and probabilistic. Large numbers of people do not have clear predispositions toward the political right or left and these people are “in play.” Efforts at persuasion should continue even though those with politically relevant predispositions will be difficult to turn. Approval of the other side is not what we advocate but the political system will be a happier and more productive place if political adversaries are viewed not with scorn but with a perhaps grudging recognition that they experience a different world.

This means accepting that political orientations are connected to deep physiocognitive predispositions in a broadly predictable fashion. Acceptance of this belief requires rejecting two widely accepted assertions. The first is that all politics is culturally and historically idiosyncratic since one society might be concerned with famines and droughts, another with the super-power across the river, and yet another with protecting mineral riches. If this assertion is true, it becomes pointless to try to generalize about political divisions, patterns, and viewpoints. The second assertion is that, though humans’ physical traits obviously vary, we all share the same basic psychological, emotional, and cognitive architecture. If, from a behavioral point of view, human architecture is all the same, it follows that differences in political orientations cannot be more than skin deep and physiocognitive predispositions are irrelevant.

Both assertions—one about the nature of politics and one about the nature of humans—are incorrect. In fact, they have it exactly backwards: Though traditional wisdom asserts that politics varies and human nature is universal, in truth politics is universal and human nature varies. Failing to appreciate these two points renders it impossible to grasp the true source of political conflict. Accordingly, before we present empirical evidence documenting the deep-seated psychological, cognitive, physiological, and genetic correlates of political variation (Chapters 4–7), we first need to make the case that politics is universal and human nature is variable (Chapters 2 and 3, respectively).

Notes