[If political attitudes are genetically influenced] it would require nothing less than a revision of our understanding of all of human history, much—if not most—of political science, sociology, anthropology, and psychology, as well as, perhaps, our understanding of what it means to be human.

Evan Charney

Everyone is entitled to their own opinions but they are not entitled to their own facts.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan

Conservaton is, for some people, the perfect place to live. Its neighborhood watch program is vigorous but hardly needed because people are law abiding, not to mention heavily armed. The schools emphasize discipline and respect for authority, and build their curriculums around rule-based instruction like phonics for reading and memorization of formulas for math. Conservaton’s similarly designed houses are well maintained, clad in pretty much the same two colors of vinyl siding, and fronted by beautifully manicured lawns. There is a church on nearly every block and congregants give generously to them. Conservaton is quiet after 10:00 pm. Actually, it is quiet pretty much all the time except for one Saturday night a month. That night, the racetrack on the edge of town attracts some of the fastest stock cars in the region along with over 1,000 loyal fans. The town takes pride in its high school football team, a perennial state championship contender that shares the field on Friday nights with a renowned, amazingly crisp, John Philip Sousa–playing marching band. The restaurants in town are cozy and familiar—they haven’t changed their menus in decades and specialize in American food and lots of it. People dress predictably and nicely. Conservatonians are a bit cliquey; they don’t take to outsiders much and are especially wary of the residents of the only other town of consequence in the county: Liberalville.

Though Conservatonians would never believe it, Liberalville is a perfect place for some people to live. The schools promote experiences rather than rules and their curriculums change with the latest educational fads and experiments. Houses are an architectural hodge-podge and Liberalites emphasize preserving the character of older buildings even if this means forgoing modern amenities. Wood floors get the nod over wall-to-wall carpeting. Lawns are unlikely to be showered with the copious amounts of chemicals and water needed to maintain thick carpets of green grass. Some residents don’t even bother mowing—they just let nature take its course and enjoy the results. The town is light on churches, but has some pretty hip bars and pubs. It also has a community theatre and coffee shops that sponsor interpretive readings and poetry slams. Along with the latest blockbusters, the movie theater makes an effort to bring in award-winning documentaries and foreign films. New restaurants are constantly popping up, and Liberalites can go out for Thai, Ethiopian, Greek, and sushi. The high school’s sports teams are a joke. The most successful is the girls’ soccer team, and even they only occasionally manage a .500 season. The marching band is equally bad, but the improvisational jazz group is nationally known and regularly wins awards. Local kids in Liberalville are always forming and reforming garage bands, some of which turn out to be very good. Liberalville is never quiet. People come and go at all hours and something is always happening. The loudness extends to fashion; Conservatonians wouldn’t be caught dead wearing the togs that Liberalites delight in sporting. Liberalites tend to travel a good deal, sometimes even going abroad. The population of Liberalville is much more diverse than that of Conservaton and it is not uncommon to hear languages other than English being spoken. Liberalites like this and are always interested when new and different people with new and different ways of living move in. In fact, the people of Liberalville are pretty much open to all kinds and all lifestyles with one important exception: Conservatonians.

Conservaton and Liberalville together make up a little less than 50 percent of the county’s population. Approximately halfway between the two towns is Middlesboro, which to locals is just the “Middle.” Though it covers a large area and includes a big chunk of the county population, the Middle is unincorporated and the people living there agree on little. Indeed, about the only thing that unites the people of the Middle is distaste for Conservaton and Liberalville. Outside of these three population centers, people are scattered widely across the county, most of them living far off the main highway that runs from Conservaton through Middlesboro to Liberalville. People in these outlying areas are a mixed bunch. Some of them take Liberalite or Conservatonian traits to an extreme degree, some (like “libertarians”) mix and match these traits, others simply couldn’t care less, and still others defy categorization.

The stark differences between Conservaton and Liberalville would fuel little more than a healthy town rivalry except for one thing: Residents of the entire county need to make collective decisions about a range of important public policy matters. Consistent with their starkly contrasting lifestyles and tastes, residents of the two towns display distinct preferences on these policy matters. Conservatonians want to stop migration into the county, to come down hard on county scofflaws, to prohibit gay marriage and gay adoption, to lower payments to the unemployed, to declare English the official and only language of the county, and to require students in all schools to recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Liberalites resist all of these initiatives. They believe criminals should be rehabilitated, not punished; that immigrants should be welcomed and allowed to speak whatever language they want; and that students should decide for themselves whether they want to be allegiant to their county, or anything else for that matter. Pretty much on any and every issue, Liberalites and Conservatonians find themselves on opposite sides of an often-heated argument.

The hardened stylistic and policy differences of the two towns results in a county decision-making process that is polarized and sclerotic. Liberalites and Conservatonians pay to put competing billboards around the county and back-and-forth name-calling is common. While acrimony between the two towns is palpable, those who live in the Middle find the whole schism puzzling, irritating, and immature. More than anything they want the bickering between Conservaton and Liberalville to cease defining life and politics in the county. It’s a vain hope—even though the two towns do not account for a majority of the county’s population, they do account for a majority of the strong believers. Residents of the county’s hinterlands exacerbate the problem; though many loudly decry Liberalville and Conservaton, they often display traits and hold positions similar to one town or the other. Others rail at Liberalites for not being Liberalite enough or excoriate Conservatonians for abandoning the true Conservaton ethos. And so it goes. The Liberalville-Conservaton divide dominates the county’s politics just as their less metaphorical progenitors have dominated politics in societies from time immemorial.

Neither town “gets” the values and politics of the other town. They both know in a deep, fundamental, and unshakeable way that their own values and ideas are clearly and obviously the best hope for a better county. Given this, they are puzzled that the denizens of the other town can bear to live there and are shocked whenever anyone expresses a desire to move to that locale. Mistrust between the towns runs deep: Each town believes the other engages in trickery, misleading issue framing, media shenanigans, and forced socialization of youth. Both believe some form of brainwashing must account for the weird, almost cult-like attitudes and behaviors that ripple out from the power centers of the opposing town. How else to explain the propagation of obviously faulty preferences for society and politics?

Residents of each town are convinced the other’s propaganda machine must be countered. If people can only be pried away from the lies and presented with the truth, they will reject the despicable ways of the offending town. Cultural misinformation provided at schools, on billboards and television, during dinner and work, and over the Internet thus needs to be corrected so that the truth can be revealed, allowing the division between the two towns to vanish in a sea of equanimity. The residents of each town spend their time alternatively in puzzled disbelief, in sneering contempt, or in quixotic efforts to show residents of the other town the error of their ways. Both sides are convinced that if only people in the other town would confront the facts and analyze them rationally, they would all move.

There is no way that the citizens of Conservaton and Liberalville will ever live happily ever after in political harmony and agreement. Anyone who says different is just naïve. Liberalites and Conservatonians are miffed at the very existence of the other town and believe that, with enough effort, those in the other town can be talked out of their misperceptions and flawed behaviors. The truth, though, is that this approach will never solve the underlying conflict, because the beliefs and behaviors of the other town are being driven by predispositions and not a lack of information. The unfortunate fact that no one in Conservaton or Liberalville recognizes is that predispositions, most definitely including their own, are often more powerful than information, even if that information is truth.

The Earth Is Round; No, It Isn’t

One of the most momentous issues in the United States during the last quarter century was how to respond to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on New York and Washington. One major response was the near-immediate invasion of Afghanistan, a nation that, under the leadership of Mullah Omar, gave aid and sanctuary to al-Qaeda mastermind Osama bin Laden. The general attitude seemed to be that if you harbor and protect terrorists who commit mass murder in the United States then you richly deserve a visit from the 82nd Airborne. More controversial was the decision 18 months later to invade Iraq. The warrant for doing so, as enunciated by George W. Bush and his administration was, to say the least, less clear than the justification for invading Afghanistan. Admittedly, Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein was a bad guy. He and his sons were responsible for an untold number of atrocities and brutalities. Yet this fact hardly distinguished him from several other world leaders with blood-soaked resumes whose countries were not invaded. Why go after Hussein in particular? The United States already had one war on its plate and Iraq, by all accounts, had no role in 9/11. Yet the events of 9/11 bred a new, muscular foreign policy that disliked nation states believed to be antithetical to the American way of life. The Bush administration’s primary justification for invading Iraq was that Hussein had weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and that these could end up in the wrong hands. Bush advisor Paul Wolfowitz, for example, said WMDs were the “core reason” for the war with Iraq.

Yet as the Iraq War continued, prewar doubts about the existence of Iraqi WMDs grew. It soon became clear that the teams scouring postinvasion Iraq could not find WMDs because there weren’t any to be found. A key CIA informant in Iraq admitted that he had lied about the existence of WMDs and then watched in horror as that lie was used as a justification for the invasion. President Bush soon acknowledged that the claim that Hussein had WMDs was the product of an “intelligence failure.” By 2005, the absence of WMDs at the time of the U.S. invasion had become an established fact. President Bush admitted there were none and so did Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. It was no longer open for interpretation; Iraq did not have WMDs.

Perhaps there the matter would have remained except for the work of political scientists Robert Shapiro and Yaeli Bloch-Elkon.1 Using survey data from 2006, they found that many Americans still believed that “Iraq had WMDs at the time of the U.S. invasion” and the breakdown of believers by party revealed striking differences. Only 7 percent of self-identified Democrats agreed that Iraq had WMDs compared to nearly half (45 percent) of Republicans. More than a quarter (28 percent) of Republicans were convinced that the United States had actually found WMDs in Iraq. Note that this was not an opinion poll. People were not being asked whether invading Iraq was a good idea or if Vice President Dick Cheney was a good guy. They were essentially asked: Iraq had WMDs at the time of the U.S. invasion, true or false? Responses to this question can be objectively graded, and a big chunk of people flunked—they replaced fact with an apparently more ideologically comforting fiction.

Conservatives are certainly not the only ones who have trouble with the facts. Presented with evidence of the Soviet army’s invasion of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, members of the French Communist party often denied such events occurred. Note that the French Communist party was not a fringe group in the 1950s and 1960s; in fact, during those years, it was the largest left-of-center party in French politics and claimed the political loyalty of a big chunk of the electorate. It was a mainstream party whose ideology and values made it averse to acknowledging any flaws in the workers’ paradise that was the Soviet Union. So when it came to Soviet strong-arm tactics in East Europe they would simply claim the information—that is, the clearly established fact—was a fiction.2 As researchers presented more and more evidence, including pictures of Soviet troops beating up and sometimes killing Czech workers, the French Communists, often with great anguish, would sometimes reverse course and very reluctantly acknowledge the truth. For some, the evidence concerning Soviet actions was so directly contrary to their worldview that they became physically ill. Opting for comforting fiction over unassailable fact is clearly not limited to one end of the ideological spectrum.

That people are often misinformed about politics is hardly news. Entire books have been written on how people in general and Americans in particular are factually challenged when it comes to politics.3 One oft-noted error concerns the percent of U.S. government expenditures going to foreign aid. The actual figure is vanishingly small, well under 1 percent, yet survey respondents consistently put it much higher, sometimes well into double digits. Respondents to one survey estimated that an astonishing one of every four dollars spent by the federal government went to foreign aid. Then they said their preference would be to “cut” that figure to about 10 percent. This would take some Alice in Wonderland math; essentially they were asking that foreign aid spending be cut by increasing it 1500 percent.4 Our favorite factual error comes from a survey asking people to identify the source of the quote, “[F]rom each according to his ability; to each according to his need.” Forty-five percent of Americans proudly assert that this phrase is the U.S. Constitution when it was actually written by Karl Marx, who no doubt would take some glee in this particular mistake.5

Still, general ignorance is not what is interesting about the Shapiro and Bloch-Elkon research because their study is not really about how little people know about politics. What they demonstrate is that in politics, ignorance is not random; factual errors are targeted in a particular direction. Conservatives rewrite history to justify the decision of a Republican administration to enter into a war that, by the reasoning of its architects, was quite possibly unnecessary. Communists rewrite the history of the Prague Spring to expunge the murderous culpability of their model state: the Soviet Union. If the facts get in the way of your preferred worldview, just unwittingly “misremember” the facts. This pattern of behavior is consistent with recent research showing that once people adopt a preferred political candidate, new negative information about that candidate leads them to intensify rather than lessen their support.6

It gets worse. In the largest study ever of “false memory,” scholars presented volunteers with accounts of five unrelated news events, each accompanied by a photograph. Unbeknownst to research participants, one was a complete fabrication with a photoshopped accompanying image. Yet half of the people said they distinctly remembered the fake event happening; 27 percent even said they saw the nonexistent event on the news.7 The pattern of these false memories was not random. One of the fake events was President Obama shaking hands with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad—Holocaust denier, main proponent of the Iranian nuclear program, and sworn enemy of Israel. Another concerned President George W. Bush vacationing with a famous athlete during the midst of Hurricane Katrina. Both were completely fake. President Bush was in the White House when Katrina ravaged the Gulf Coast and President Obama has never joined hands with Ahmadinejad. Yet many survey participants not only confidently remembered those two events, they explained just how they felt at the time they first learned of the event. The punchline, of course, is that conservatives were much more likely than liberals to falsely remember the Obama-Ahmadinejad handshake (by better than a 2 to 1 ratio), while liberals were significantly more likely than conservatives to falsely remember the inappropriately timed Bush vacation. So not only do people refuse to remember unflattering things about those with shared predispositions, they also make up unflattering things about those who have opposing political predispositions. People with different politically relevant predispositions appear to live in worlds with distinct sets of facts. It would seem Moynihan’s famous statement quoted at the beginning of this chapter does not always apply.

Driven by their fundamental differences in predispositions, liberals and conservatives believe the facts that support their predispositions even when they are not real facts, and once people have erroneous beliefs it is extremely difficult to correct them, since their instinct is often to dig in their heels. This being the case, the logical inference is that it will be virtually impossible to get liberals to become conservatives or conservatives to become liberals. Is this true? Do we choose our political beliefs or do they emerge out of predispositions that are at best only partially under our control?

Sex and Politics: Do We Have a Choice?

Actress Cynthia Nixon, better known to millions as Sex and the City’s Miranda Hobbes, says that she is gay by choice. “Why can’t it be a choice?” she asks.8 Well, clearly for her it can. She had a long-time relationship with Danny Mozes, who fathered two of her children, and she did not switch teams, as it were, until well into adulthood. Fair enough. The United States is a free country and she exercised that freedom to opt into a same-sex relationship. Making that choice, though, has irked many people. Liberal gay rights advocates worry that Nixon is willingly falling into a “right-wing trap.” John Arovosis, a Democratic political consultant and gay activist, argues, “When the religious right says it’s a choice, they mean you quite literally choose your sexual orientation, you can change it at will and that’s bull.”9 Liberals like Arovosis seem quite comfortable with sexual orientation being biologically based rather than a lifestyle choice reflecting cultural constraints and our mood of the day, but they are often decidedly uncomfortable with any other orientation being biologically based.

To see what we mean, let’s take a short walk back in time. Forty years ago, Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson argued that social traits like cooperation were almost certainly shaped by evolution.10 As long as Wilson was talking about ants, his ideas were given a respectful reception, which was not surprising given that they made theoretical sense and were backed by solid evidence. But when he extended the same ideas to humans, in effect saying that human nature was rooted in biology, he triggered a huge backlash from the political left. Well-known liberal intellectuals like Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin lined up to bash the notion that social characteristics were biologically rooted. They believed Wilson was guilty of “biological determinism,” or at least social Darwinism. The International Committee against Racism (CAR) claimed that by encouraging “biological and genetic explanations for racism, war and genocide,” Wilson “exonerates and protects the groups and individuals who have carried out and benefited from these crimes.”11 Left-leaning academic groups like Science for the People denounced the notion of a meaningful genetic basis for social traits, and scholars from various disciplines banded together to write letters to national publications declaring that “(sociobiology) has no scientific support, and … upholds the concept of a world with social arrangements remarkably similar to the world which E. O. Wilson inhabits.”12 In a nutshell, Wilson’s opponents accused him of using science to justify the social status quo and anyone who does that must be a conservative—except Wilson isn’t.13 Things got so bad that at one conference a group of CAR activists interrupted a presentation by Wilson, called him a racist, and dumped a pitcher of water over his head.14

The same battle lines cropped up two decades later when right-leaning intellectuals Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray (a Harvard psychologist and a think-tank political scientist) caused a huge stink by claiming that intelligence was genetically influenced and that high-IQ types were becoming a distinct social group that they referred to as the “cognitive elite.”15 What really got Herrnstein and Murray in hot water was their argument that those who were not in the cognitive elite tended to fall into certain sociodemo-graphic groups—for example, they were more likely to be criminals and quite a bit less likely to be well-off or white. Gould and a long list of liberal luminaries once again mounted the barricades to defend the notion that human nature is a pure product of social environment and has no heritable or biological basis.16

This war over the biological basis of social traits goes on today. Rather than rehash the pointless dispute over nature and nurture, we want to highlight the hypocrisy of both sides. Liberals fulminate that researchers are mistaking right-wing ideology for science when they find that intelligence is genetically influenced, but apparently the science is high quality when it suggests that sexual preference is genetically influenced. Conservatives argue that people need to brace up and face the implications of scientific research on the heritability of intelligence but their face-the-data stoicism goes into reverse when it comes to studies suggesting sexual orientation is heritable.

So both sides agree that socially relevant traits are biologically influenced— they just disagree about which ones. In reality, of course, the facts of biology are not structured to please one political side or the other. A wide swath of socially relevant traits—sexual behavior, intelligence, personality, and a whole lot more—appears to be influenced by both nature and nurture, not one or the other. This idea is steadily becoming conventional wisdom regarding a growing number of social behaviors, but there is one big exception: politics.

Politics is a last redoubt for hard-core supporters of a version of human exceptionalism that maintains biology always applies to other species but not always to super-special homo sapiens. And one area in which it certainly does not apply, this argument goes, is personal political temperaments. The belief is that politics is a purely cultural construct and is therefore immune from biology. Politics is the Alamo for people who deny the relevance of biology and it must be defended against assaults from Santa Annas like us, who are coming over the walls in increasing numbers, waving EMG sensors, asking for saliva samples, and showing people pictures of poo to see if it makes them sweat.

As far as we can tell, the fierce determination of the defenders on the wall is motivated at least in part by the understanding that ideas have consequences. The sad and often sickening history of the application of biology and evolution to human affairs gives legitimate cause for concern; racism, sexism, classism, and assorted other odious isms have all been supported by the antecedents of sociobiology. The eugenics movement of the first half of the twentieth century, for example, was backed by big scientific names who assured us that it was a useful, even necessary, application of new biological knowledge to human affairs. Karl Pearson, who developed the statistical methods of correlation we introduced in Chapter 1, was a respected mainstream public intellectual in the early part of the twentieth century. He was also a big fan of social Darwinism and an enthusiastic eugenicist; his view of the ideal country was one with a population “recruited from the better stocks” so that it could keep its competitive edge “by way of war with inferior races.”17

Of course, liberals sometimes like to forget that their favorite opposing “big idea”—that people are shaped exclusively by their environment—has led to its own share of atrocities. To return to the example mentioned in Chapter 3, Mao’s notion that people could be changed just by forcing them to move from fetid cities to noble pastures resulted in millions of deaths. If the conclusion is that ideas matter, we are on board; if it is that giving weight to environmental influences on behavior is good but doing the same for biological influences is bad, we are disembarking. An unrelenting faith in the ability of social context to mold behavior is hardly a source of tolerance, as gay rights advocates know all too well. All knowledge can be put to good or bad uses. The knowledge (in the form of empirical findings) presented in this book is neither inherently dangerous nor universally depressing. Let us try to convince you that acknowledging the role of biology and deep psychology in shaping political orientations could, under the right circumstances, do some good.

Taking Political Predispositions Seriously

The material presented in this book cannot eliminate the forces behind diverse political orientations and will not end political polarization or pave the way for a universally productive and trusted political system. Nonetheless, it has the potential to improve the political climate. This book has been about political predispositions. These predispositions, as we hope is clear by now, run much deeper than the sources of attitudes presumed by the citizens of Conservaton and Liberalville to shape beliefs: billboards, schools, families, and talking heads.

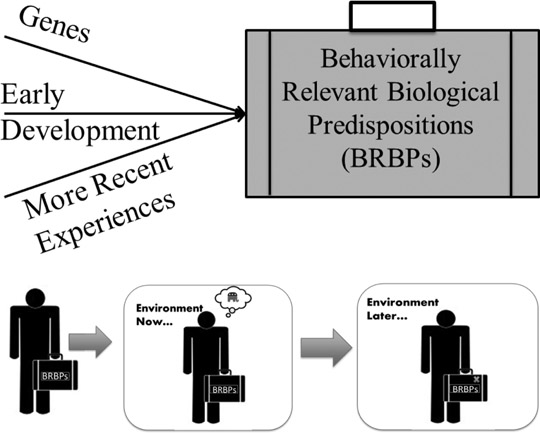

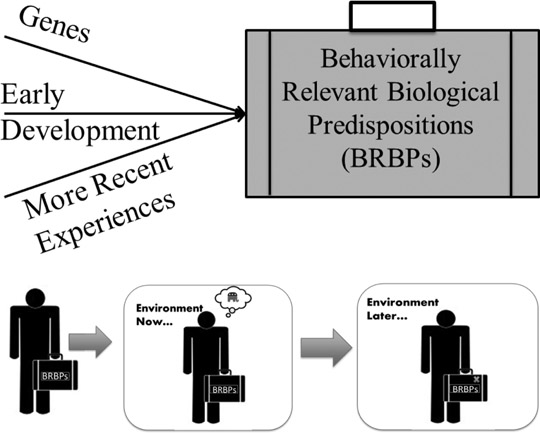

As depicted in the top part of Figure 9.1, because of genetics, early development, and subsequent life experiences, people carry with them distinct brain response patterns, sympathetic nervous systems, values, moral foundations, negativity biases, strategies of information search, tastes, preferences, and, it would appear, even different “facts.” These differences coalesce into what we have been calling predispositions or, to be more precise, behaviorally relevant biological predispositions (BRBPs for short).18 Person-to-person variations in predispositions connect directly to variations in “neuroception,” a term coined by psychophysiologists to describe the fact that physiologies are constantly scanning and evaluating the environment and generating signals about what is safe and approachable and what is threatening and deserving of a wide berth.19

Figure 9.1 The Bases of Behaviorally Relevant Biological Predispositions and the Interactions with the Environment

Neuroception often takes place outside of conscious awareness but makes itself known in our emotions, in whether we feel that something is worth a taste, revolting, the right thing to do, or just not right. In other words, neuroception is the way people perceive and experience the world.

Individual differences in biology connect to individual differences in neuroception, and since neuroception monitors the sociopolitical environment, those biological differences can and do correlate with political attitudes. In other words, the structure, wiring, and processing of their central and autonomic nervous systems leads some people to find certain stimuli instinctively and intuitively appealing while others find them repellent, just as it leads certain people to care about a given outcome while others do not care at all. Since public policies can alter the likelihood that particular stimuli will make an appearance, it is not surprising that these physical characteristics affect politics. As a result, in a given situation, preset response tendencies (that is, the predispositions we carry with us) shape political views and opinions, even though people often deny it.20 Once these predispositions exist, people try to mold the world to fit them (rather than the other way around) and this is why the two ideological camps often end up with different sets of facts. Liberals mold the world their way, conservatives mold it theirs, and the result is a big divide on many different topics.

Most people seem to wander around thinking that their political views are “common sense” or “normal” and that a majority of their fellow homo sapiens either already agree with them or would agree if they rationally thought things through. Psychologists term this “false consensus.” Moreover, people assume that those who do subscribe to aberrant political viewpoints could be persuaded otherwise with only a handful of simple ingredients: a few facts, a dollop of logic, and a pinch of persuasion. Mix that together and feed it to reasonable people, and they will adopt your political perspective, whatever that happens to be. Anyone who persists in holding the opposite viewpoint must be irrational or pigheaded, so no wonder their political ideas are half-baked. This set of beliefs about the nature of political differences is why Liberalites and Conservatons spend so much time gridlocked and yelling at each other. They fundamentally misunderstand why the other side holds the views it does.

A central implication of the evidence we have summarized is that people are always going to have different points of view and not merely because they are information deficient or obdurate. As such, our message is perfectly consistent with that offered by others,21 but takes the point to a deeper level by tracing the differences in such concepts as moral foundations and personal values all the way to sub-threshold physiological and cognitive traits and biases (and possibly even genetics) of which people have no conscious awareness. Even so, this does not mean change is impossible.

As indicated in the bottom half of Figure 9.1, when certain environments act on an individual’s behaviorally relevant biological predispositions, particular thoughts, decisions, or actions result. Maybe the person demonstrates an affinity for one political party or the other. This earlier environmental context as well as the resultant thought, decision, or action it engendered might not have any lasting effect on the person’s BRBPs and therefore would not be expected to lead to any alteration in subsequent thoughts, decisions, and actions. (In fact, we would argue that this is the norm and that is why political views are so stubbornly held and rationality and compromise are so difficult to locate.) However, on other occasions, the BRBPs might be altered (indicated by the “X” on the suitcase in the figure) by a poignant and powerful feature of the environment—perhaps not altered by much, but enough that slightly modified predispositions will be carried into later environments. Predispositions can change, but they do not do so often.

The major reason to retain and even refine your powers of political persuasion is not the likelihood that you can convert the politically predisposed (though being able to put yourself in their shoes might help some), but the possibility of influencing the large number of people who lack such predispositions. They might actually respond to good arguments and fresh evidence. We recommend not wasting your breath on those who are predisposed toward political positions that run the opposite of yours. The payoffs of working on this group are just too small. You may derive some twisted satisfaction from trying to move the unmovable, but the effort tends to pollute the whole political climate. Slices of the population on both the political left and the political right are predisposed, and therefore for all intents and purposes unpersuadable. Unfortunately, those who have these predispositions tend to be the ones who are the most politically motivated, the upshot being that the most intransigent among us tend to have disproportionate influence on the nature of the political system.

On its face, the existence of biologically grounded political predispositions seems an incredibly depressing situation for those wanting to improve political arrangements in the United States or elsewhere. However, we believe a silver lining accompanies the increasingly documented existence of political predispositions. Though political predispositions distort facts, hinder political communication, sow mistrust, and even initiate violence, they bring benefits as well—as long as we are made aware of their existence. Properly handled, the realization that political views are shaped by predispositions can help each of us to understand ourselves, understand our political opponents, and understand the best design for political systems. If acknowledging the fact that political temperament is traceable in part to biology requires modifications of both canonical thinking in social science disciplines and hackneyed interpretations of human history, as Professor Charney suggests in the quote that opens this chapter, we say that isn’t all bad. After all, look where the old interpretations of history and applications of the social sciences got us. It is high time to embrace the real version of humanity, not the one that makes us feel good but in actually is quite unhealthy in the long run.

Know Thyself; Know Thy Enemy

If you are a conservative, do not read the next few paragraphs, as they are designed solely for liberals and are meant as a private counseling session intended for them only. Liberals: Quit wasting your time spluttering about the ignorance of conservatives or trying to convert any and all of them. As F. Scott Fitzgerald might have put it, “The very conservative are different from you and me.” Where you see a titillating curiosity, they see an imminent danger; where you see something potentially edible (with the right mole), they see disgustingly spoiled produce; where you see an excuse to hire a domestic worker, they see unmitigated chaos; where you see intriguing ambiguity, they see debilitating uncertainty. They spend more time than you focusing on negative events—particularly negativity that is tangible and immediate. They see problems that are not there. They “remember” events and visions that never were. They refrain from seeking new information simply because it might not be information that is helpful or confirming. They are comfortable with revered and long-established sources of authority such as religious orthodoxy and the words of the country’s founders. On the other hand, anything that reeks of human discretion, like modern governments and a broad application of scientific investigation, is suspect. Their first instinct is to assume those in faraway lands have questionable values, do not share our country’s interests and goals, and should not be trusted. Conservatives prefer established ways of doing things and have less craving for new experiences—culinary, social, literary, artistic, and travel—than you do.

Their enhanced focus on negative events and situations should not be mistaken for fear. Au contraire! They do not run from the negative. They attend to it, eye it warily, and ponder how best to minimize its influence and impact. They don’t like being told what to do, especially by people who are not part of their in-group, because they don’t trust the judgment of other human beings. They think the only hope for mankind is to embed it in hierarchies and rules, to remove individuality and discretion by following inviolate texts and the dictates of the free market that, thanks to Adam Smith’s invisible hand, work automatically on the basis of supply and demand. They think rules are good as long as they derive from the proper authorities.

You should not expect them to change, but rather should work with who they are. Try to see the world from their perspective. Work at thinking like conservatives think and experiencing what conservatives experience. Enter their world not by actually going undercover but by attempting to adopt the psychological mindsets that make conservatives conservative. If that is not doing it for you, come to our lab and, for a small fee, we will condition you to attend like a conservative to negative stimuli, looming disorder, and mild ambiguity. You will know you have succeeded when you “dream conservative.”

This is where conservatives need to come back and liberals need to leave. More specifically, if you are a liberal, do not read the next few paragraphs as they are designed solely for conservatives and are meant as a private counseling session for them only. Conservatives: Quit wasting your time spluttering about the ignorance of liberals or trying to convert any and all of them. To paraphrase Fitzgerald, “The very liberal are different from you and me.” Where you see an imminent danger, they see a titillating curiosity; where you see disgusting spoiled produce, they see something potentially edible; where you see unmitigated chaos, they see an excuse to hire a domestic worker; where you see debilitating uncertainty, they see intriguing ambiguity. They don’t pay nearly as much attention as you do to negative situations and potentialities and, if they do worry at all about the negative, they seem strangely unmoved by the immediate threat of malevolent human beings. Sometimes it seems as though they worry more about climate change and endangered species than terrorism and crime. They are firmly convinced that, despite all evidence to the contrary, humans can change under the right circumstances.

All this makes liberals far more trusting than they have any right to be, but it is important to realize that this is not because they are foolish or lazy but rather because they are structured in such a way that prevents them from appreciating the obvious dangers swirling about. They seek out new information even without knowing where it might lead and even when that new information might be contradicted by even newer information. None of this particularly bothers them, as they just like the idea of moving from new thing to new thing as though novelty were its own reward. They really believe that government programs and the like will change things for the better and they are suspicious of the tried and true. They are convinced that the traditional approaches created big problems, problems that are remediable by embracing the untried and new. Their first instinct is to assume individuals in faraway lands are trustworthy. Hierarchies, on the other hand, such as those typifying the military, organized religion, and corporations, are objects of their suspicions. They love experiences that might take them off the beaten track. They seem not to look before they leap.

Their eagerness to try new approaches and experiences should not be mistaken for reckless hedonism. On the contrary! Liberals spend a good deal of their time trying to understand other people, even worrying about them. The circumference of their circle of concern extends around the globe and even incorporates nonhuman life forms. They don’t seem to consider, let alone mind, the fact that this openness raises the possibility that they could be taken in by evildoers. Because they think the human condition is perfectible, they are always trying new approaches, which usually fail. But this fact seems not to dissuade liberals from turning right around and trying something else. They like to be surprised by their food, their literature, their art, and the places they visit.

Liberals “just don’t get it” and you should not expect this to change because for liberals there is nothing to “get.” Quit wasting your time explaining to them the dangers of rampant immigration, overseas threats, and moral decay. Nothing you say will lead them to take these matters as seriously as you do. Rather, take what you now know about them and work with it. Try to see the world the way they see it. Hold in abeyance your knowledge that threats are real and try not to be bothered by what will initially feel to you as vulnerability and carelessness. Practice not fixating on the negative and work at enjoying new and unexpected experiences. Do this not with the intention of becoming a liberal but with the intention of better understanding them. Work at thinking like liberals think and experiencing what liberals experience. Enter their world not by actually going undercover but by attempting to adopt the psychological mind-sets that make liberals liberal. If that is not doing it for you, come to our lab and, for a small fee, we will condition you to attend more than you currently do to positive stimuli rather than threats, looming disorder, and nagging ambiguity. You will know you have succeeded when you “dream liberal.”

A Zebra Can’t Change Its Stripes

Okay, reading in rounds is done and we hope everyone is back. Actually, we know you cheated, and we are glad you did because the goal here is to help our readers more deeply understand differences, and especially political differences. Before you accuse us of painting with too broad a brush, don’t forget to think probabilistically. Obviously, not all conservatives and not all liberals fit the descriptions above (thank goodness!), but the general tendencies appear over and over. The larger point is that those with predispositions counter to yours do not see what you see, fear what you fear, love what you love, smell what you smell, remember what you remember, taste what you taste, want what you want, or think how you think. These differences run so deep that they are biologically grounded and, as such, cannot be changed quickly. Since political beliefs flow out of these predispositions, this means that they, too, cannot be changed quickly. It is our conviction that making an effort to understand the nature and depth of political mindsets will be beneficial since it is always good to better appreciate those with whom we are sharing the planet. Just as learning a second language assists in coming to grips with your native tongue by putting aspects of language in perspective, learning a second political orientation also puts your native orientation in perspective and deepens understanding.

In addition to self-improvement, taking predispositions seriously can improve understanding of others and therefore can enhance the state of political discourse. Recognizing that the maddeningly incorrect views of your political opponents are due less to their unencumbered choices than to traits they have little choice but to endure cannot help but increase tolerance and acceptance. Think of the improvements resulting from the recognition that being left-handed is not a choice resulting from flawed character but instead is the product of a biological (in this case heritable) disposition. Teachers are no longer disrupting classrooms and wasting time (not to mention demeaning 12 percent of the student body) by trying to beat the left-handedness out of left-handers. The entire learning environment has improved as a result. We look forward to the day when liberals are not trying to beat the conservative out of conservatives and conservatives are not trying to beat the liberal out of liberals, as we believe parallel improvements in the political system will be in evidence.

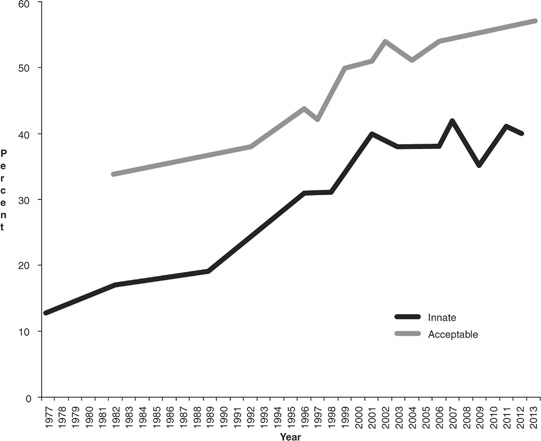

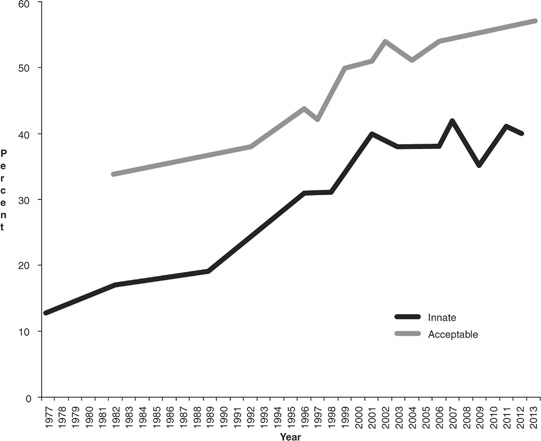

A more commonly invoked illustration of the good that can come by acknowledging a role for genetics and biology in human social behavior is sexual orientation. Gallup periodically polls people on whether they think homosexuality is a product of nature or nurture, something that a person is born with or the result of something in their environment. In 1977, only 13 percent of people believed being gay was innate, while 56 percent attributed it to upbringing. In 2012, 40 percent believed sexual orientation was something you were born with and only 35 percent attributed it to upbringing. The different beliefs in the causes of homosexuality have fairly stark implications for attitudes on gay rights. Roughly two thirds of people who think being gay is a product of upbringing and the broader environment say that homosexuality is not an acceptable lifestyle. On the other hand, more than three quarters of the people who believe homosexuality has a biological basis believe it is an acceptable lifestyle.22 Figure 9.2 tracks Gallup data over time and shows that as more people believe homosexuality is something you are born with, the percent believing homosexuality is an acceptable alternative lifestyle also goes up.

Given those numbers you get a sense of why gay rights activists get alarmed when the Cynthia Nixons of the world announce their sexual preference is purely a personal choice. The bottom line is that people who believe sexual orientation is biologically based are much more likely to be accepting of gay rights.23 Americans became more accepting of gay lifestyles and gay rights because they started to accept the growing evidence that sexual orientation is less a moral choice than simply a part of people’s biology.24 This shift in perceptions of the

Figure 9.2 Percent of People Believing Homosexuality Is Innate and Homosexuality Is an Acceptable Alternative Lifestyle

source of homosexuality almost certainly helped the political conversation over gay rights to take place within the appropriate democratic and legal context. This is a stark example of an awareness of the role of biologically based predispositions helping to generate tolerance for different points of view.

In a roughly analogous fashion, this is the way people should be thinking about the sources of differing political orientations, and when they do, we predict that the implications will be similar. If recognizing that sexual orientation is anchored partially in biology leads to greater tolerance of different lifestyle choices, recognizing that political ideology is also tied to biology will lead to greater tolerance of different political viewpoints. We don’t mean tolerance in an everybody-is-special PC sort of way; we mean tolerance in the sense of an acceptance that the world is always going to have people with political temperaments very different from our own. A defiant chant of the gay rights movement is, “We’re here. We’re queer. Get used to it!” It is the same for ideology. There will always be people with different political orientations from yours, people whose viewpoints you revile. Get used to it, and for the sake of all of us, go one step further—accept it.

This kind of acceptance directed at predispositionally driven variations in political beliefs would not mean you have become a traitor to the cause. We need to get past the stage where liberals/conservatives are in a contest to show that they are the most outraged by their ideological opponents. It would not even mean that you were any less convinced that your political opponents are wrong. You would just be acknowledging that the reason they are wrong is largely beyond their control. This in itself is a major step forward. Accept that the main reason your political opponents hold the views they do is not laziness, a lack of information, or willfully bad judgment, but rather physiological and psychological contours that are fundamentally different from yours. If you had the same predispositions they do, it is likely you would have political opinions similar to theirs. Whenever you meet a conservative/liberal your response should not be, “What a shallow idiot,” but “There but for the grace of God go I.”

In his book The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt describes making just the sort of adaption we are suggesting. Haidt discusses an extended stay in India, a socially conservative society with many traits (patriarchy, hierarchy, extreme inequality) at odds with his beliefs. Though initially disturbed, Haidt also recognized and appreciated the courtesy and hospitality of his hosts and the Indian people more generally. He began to see the dense “moral matrix” and how it supported a vibrant, family-centered social order. He returned to America to find, somewhat to his own surprise, that he was no longer reflexively puzzled by or angry at social conservatives. He still didn’t agree with their policy stands, but found himself less viscerally committed “to reaching the conclusion that righteous anger demands: we are right, they are wrong.”25 What we are suggesting is that you don’t need an extended stay in a foreign culture to get to the same point. Just recognize the existence of biologically based predispositions and the implications this recognition holds for politics, and you are most of the way there.

So believe in your opinions; they are likely the correct opinions for you. But recognize that they are not the correct ones for everybody. Be humble about them and recognize that they will not and cannot lead to the kind of society everyone wants because not everyone has the same perceptions of reality and therefore of the most desirable social arrangements. If everyone saw and experienced the same world, you could be more confident that your beliefs were correct and should be broadly applied. Since this is not the case, your beliefs are not such a big deal and humility should be the order of the realm. If people internalized these facts, political debate would be different and better.

A deep irony in all this is that, by demonstrating the major differences in people’s visions and experiences of the world, science is increasingly supporting a concept long favored by rabidly antiscience deconstructionists. Deconstructionists believe there is no objective reality because everything is in the eye of the beholder; that there is no text until the reader brings his or her own interpretations and experiences to it. Our take on this improbable confluence is likely to alienate both sides. The deconstructionists are right in positing that, because of the significant variations in neuroception, when it comes to topics such as politics there often seems to be no objective reality. However, these differences across people can (and should) be studied scientifically in order to understand the nature and implications of variations in people’s perceptions. Come to think of it, that is exactly what we are doing.

Talking Conservative/Speaking Liberal

Historically, the two sides have a hard time talking to each other because they often speak a different language. This sort of argument has been made most famously by George Lakoff, a cognitive linguist at the University of California–Berkeley. Conservatives, argues Lakoff, frame their arguments in the language of the “strict father,” a metaphor for their preferred relationship between government and the governed. Liberals, on the other hand, use the language of the “nurturing parent.” Lakoff contends that their different languages make it difficult for conservatives and liberals to comprehend each other. He also argues that the conservative strict father approach resonates more with the broad electorate, which is why conservatives (at the time he was writing) were doing a better job capturing the support of middle-of-the-road voters. Lakoff suggests liberals take a cue from conservatives and adopt the language of the strict father.26

Though our predispositions perspective is consistent with Lakoff’s notion that conservatives and liberals see, understand, and especially describe the world differently, its tactical implications are quite different. We doubt the effectiveness of liberals speaking a language other than their native tongue. Liberals attempting to talk tough and strict, even though doing so defies their predispositions, are likely to appear as inauthentic as Michael Dukakis in a tank or Barack Obama shooting skeet. Moreover, even if liberal politicians attract a few moderates and conservatives by becoming strict fathers and mothers, liberal followers are even more likely to turn off and tune out. Likewise, conservatives suddenly trying to come off as nurturing would be no more effective than Dick Cheney attempting to smile or 2012 Republican vice presidential nominee Paul Ryan’s widely ridiculed soup kitchen photo op. Predispositions are real, and ordinary people are amazingly good at intuiting who does and does not share their predispositions, even though they may not be conscious that they are making these judgments.

When people feel a candidate is one of them, they will cut that candidate an amazing amount of slack on policy and personal matters. If they sense something is off, support will be half-hearted at best. Consider the strained relationship of 2012 Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney with true conservatives. It wasn’t just his Mormonism or his embrace of healthcare reform when he was governor of Massachusetts; more generally, he just did not seem to have that conservative swagger, vocabulary, mindset, and look in the eye. True-believing conservatives serially fell in behind every other possible potential nominee in the primary race and then backed Mitt Romney only when each of those alternatives imploded and nobody else was left. The only thing that dispositional conservatives found exciting about Governor Romney in the general election was that he was not Barack Obama. Regardless of policy stances, he would never be one of them.

The point we are making is that, unlike Lakoff, we do not believe that predispositions can be “gamed.” Artificially adjusting adjectives will not sway those who have predispositions, and the middle ground is a mixed and unpredictable bag. Pretending to be something you are not is rarely a successful strategy in the long run. Besides, though the cycle will no doubt continue its ups and downs, recent electoral results suggest that the “liberal” nurturing lingo may not be as big a loser as Lakoff implies. We do not see the existence of predispositions as a particularly propitious platform for one group to bamboozle the other (or even to bamboozle those largely devoid of predispositions—they are pretty good at spotting fakes too). Understanding predispositions does not necessarily create an opportunity to achieve a strategic political advantage, but rather constitutes a much more mundane but perhaps more important opportunity to improve acceptance. This acceptance is more crucial than ever in our increasingly interconnected world. As Shankar Vedantam puts it, “[O]ur mental quirks and biases once affected only ourselves and those in our vicinity. Today they affect people in distant lands and generations yet unborn.…Today, subtle biases in faraway minds produce real storms in our lives.”27

Building a Better Mousetrap

The predispositions argument does not mean that you need to agree with viewpoints that contrast with your own—far from it—but it does have several potentially valuable implications for the type of political system that might best manage these disparate predispositions. For starters, longing for a political system devoid of ideological and partisan differences is pointless. George Washington never actually delivered his famous farewell address (it was merely published in leading news outlets), but the most remarked passage in it laments “the mischiefs of the spirit of faction,” which at the time was taken to mean groups of people united by a common impulse, passion, or interest. Washington noted that factions “distract public councils … enfeeble public administration … agitate the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms … [and] kindle animosity of one against another.” We concur with Washington— factions do all this and more—but we disagree with his preferred solution, which seems to consist of little more than a plea that factions “be discouraged.”

Political factions are built on the foundation of biologically instantiated predispositions. As a result, you can “discourage” all the live-long day if you want, but they will not go away. They will, however, take on contours reflecting the irreconcilable antagonism between the forces of tradition and innovation. Though we share Washington’s frustrations with factions—they are strong, resilient, and irritating—we prefer the approach of another founder, James Madison. Madison also was frustrated with factions (not surprising, since he had a big hand in writing Washington’s Farewell Address), but in his masterpiece, Federalist #10, he recognized that “the latent causes of faction are sown in the nature of man.” Madison is so on target that we can’t resist allowing him to continue: “A zeal for different opinions … [has rendered people] … much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to cooperate for the common good.” And finally, “[S]o strong is this propensity to fall into mutual animosities that where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions and excite their most violent conflicts.”28 We could not agree more; indeed, Madison could be writing an incisive commentary on modern American campaigns. If there is nothing important about which to argue, something frivolous and fanciful will do just fine!

Madison suggests two mechanisms to do away with factions and bring political combatants like Liberalville and Conservaton into unity and amity. The first option is to destroy the liberty that allows people to pursue their differing impulses and interests; the second is to force every citizen to hold the same opinions and passions. Noting that the first is a cure worse than the disease and the second is wholly “impracticable,” Madison quickly proceeds to a discussion of the best ways to mitigate the effects of faction. To cut to the chase, Madison’s central suggestion for governing in the face of factions is the implementation of representative rather than direct democracy. He believed that people should not be expected to make political decisions for themselves, but rather urged that a small number of citizens be chosen to represent the differing wishes of the many, so that they could “refine and enlarge” the public views. Madison thought representative democracy was particularly valuable, even essential, to the maintenance of large political systems where direct democracy would be both dangerous and impossible. The basic logic is that since people are inspired to form factions, we must empower a select number of individuals who, if they want to keep their positions, have to pay attention to the interests of more than their own faction. The system Madison created may be failing to accomplish this, as the leaders themselves get pulled ever more into the factional morass above which Madison expected them to rise, but his instinct to mitigate factions rather than wish them away is well-founded

Representative democracy is not guaranteed to solve the problem of factions; direct democracy, though, is guaranteed to exacerbate the problem of factions. Consider a variant of direct democracy known as deliberative democracy, which has attracted extensive attention from political scientists. The basic idea is to get ordinary people together so they can hash through particular questions or issues. In certain iterations, the citizens are given access to information and experts. The hope is that the participants will distill a consensus that accurately approximates the “will of the people”; in other words, a representation of what public opinion would look like if people were informed, engaged, and stripped of false consensus. Various deliberative democracy experiments have been conducted and sometimes report a softening of harsh opinions.29 Unfortunately, research also shows that any impact of deliberative democratic processes is contingent and limited. It is contingent both on the type of issue under discussion being an easy or “nonzero-sum” issue and on the participants being unusually interested in politics. Even then, any effect is limited to an unrealistically short period of time after the experiment. In truth, most people do not change much even after hearing the thoughts of fellow citizens or being provided with a little more information. Tellingly, the only changes of note tend to come from those who are truly undecided going in.30

In short, even when social scientists have given consensus-building the old college try in the most congenial of circumstances, very strong—perhaps irreconcilable—differences in political views remain. We are not surprised, since changing predisposed people’s minds, especially on issues relating to the bedrock dilemmas of politics, is not done easily. Other variants of direct democracy, including New England–style town meetings, have similar problems, and the existence of what Washington and Madison call factions and what we call predispositions is a reason to embrace representative government as our best hope. The key is for people to recognize that government is taking place in the context of these widely varying predispositions. When you do not get what you want, it is important to recognize that it is not because of a conspiracy or some structural flaw but because some people have vastly different predispositions than you do.31

The predispositions perspective does suggest (or more accurately, reinforce) arguments for institutional reforms that might reduce or at least better manage ideological conflict. These mostly deal with the structural elements of political systems that allow the Conservatons and Liberalites of the world to disproportionately define choices about collective action. Obvious examples in the United States are primary elections and redistricting. Compared to general elections, primary elections tend to be low-profile affairs. Those who cast ballots in these elections, and the groups that recruit and support candidates, tend to be more ideological than the general electorate. This helps explain the lament of many American voters put off by what they see as the overly ideological bias of both the candidates they have to choose between in a general election. The more moderate candidates—the ones more likely to focus on political practicalities than partisan point scoring—often don’t make it past the primary. A reformed system that allows residents of the Middle a more meaningful role than choosing between a hard-right Conservaton and a hard-left Liberalite would make more room for candidates and politics that can bridge the gaps.

Similarly, in many states the decennial chore of redrawing the geographical boundaries of congressional districts highlights and exacerbates ideological predispositions rather than helping to mediate between them. Redistricting often amounts to little more than a brutal cartographic war between partisan camps jockeying for electoral advantage; in effect, a duel with maps in which the winner gets to institutionalize the interests of their predispositions. If you want democratic politics to have a more practical tilt to it, then it’s probably not a good idea to put the job of geographically defining representation into the hands of people and groups with strong incentives to let partisan self-interests push aside all else.

While understanding the relevance of predispositions supports these sorts of institutional reforms, its real message is aimed at individuals. No magic institutional formula can make divided politics go away. Given the evidence presented in this book, who do you think is going to take the most interest and be the most involved in hammering out the specifics of the institutional reforms we just mentioned? When it comes to mass scale politics, it is impossible to avoid the implications of predispositions and the best that can be done is to manage these predispositions in a way that insures we count, rather than bash, heads to resolve differences. The message of the predispositions argument to those seeking a form of low-conflict politics based on mutual cooperation, interest and goals is this: Grow up. The predispositions argument, if nothing else, explains why democratic politics is so unpalatable—and also so deeply necessary.

Caveat Iterum

Several of the caveats we have been stressing throughout this book deserve repeating one last time. We will mention three. First, remember that though predispositions have a certain timeless quality to them, the issues of the day superimposed on predispositions vary widely. Fifty years ago the issue of inter-racial marriage was big. When the Supreme Court finally prohibited states from enforcing antimiscegenation laws in 1967, 16 states were affected and only 20 percent of the public approved of interracial marriage. By 2011, according to Gallup, 86 percent of Americans “approve[d] of marriage between blacks and whites,” and the matter has been settled. Instead, gay marriage is a big issue today; but in 50 years (and perhaps much less given current trends), it is likely to be as much a nonissue as interracial marriage is now. Another issue will exist, though, and it will divide those predisposed toward supporting new and those predisposed toward supporting traditional lifestyles. The evidence we have presented here says little about the coming and going of these issues (we leave that important topic to others), but says quite a bit about the type of person who ends up on one side or the other of whatever issue has been framed as a contrast between tradition and innovation.

Second, nothing in the empirical evidence or in our language should be taken to mean that one particular ideological stance is better or more natural than another. We know how the game is played, and some people will undoubtedly find an interpretation or a turn of phrase that reveals our deep hostility toward liberals or toward conservatives. This is as certain as it is depressing, leaving us to appeal somewhat forlornly to the strongly predisposed to beat down the instinct to be defensive, even if our terminology has been off-putting on occasion. The evidence of a biological and deep psychological substrate explains why so much variation in political temperaments exists today, yesterday, and tomorrow. It does not say anything about one particular temperament being better than another.

Finally, we make one last plea to think probabilistically. We have come a long way since illustrating how correlations are measured. We now have seen that correlations between physiological and psychological traits and political orientations are important; significant within studies; and consistent across studies, countries, and samples—but also modest in strength. This means that there are surprising differences between liberals and conservatives on an incredible range of traits, many not obviously related to politics, but it also means that exceptions are plentiful. Not all people who tend to prefer solutions that are characterized as conservative live in Conservaton and not all people with liberal views make a home in Liberalville. Only on average are conservatives more likely to behave like Conservatonians and liberals like Liberalites. To say otherwise would be to engage in stereotyping. Mustering one, two, or even a hundred cases that run contrary to the reported pattern does nothing to contradict the general relationships we have examined. Think probabilistically and do not pretend the research is claiming more than it is.

Conclusion: You Are Special … but Don’t Let It Go to Your Head

You were born with a unique genetic package. This package was immediately modified by prenatal and early postnatal forces, and further modified by a wide range of environmental influences during development and beyond. These sources of influence combined into dispositional tendencies that affect your behavioral and attitudinal responses to whatever situations the world presents to you. These tendencies are inertial; they structure your attitudes and behaviors but do not predetermine them. Politics might seem as though it should be immune from such predispositional forces, but in this book we have dissected a rapidly growing corpus of research indicating that this is simply not the case. The political diversity that springs from differences in predispositions will never go away, and in a surprising number of cases it can meaningfully be arrayed on a spectrum that runs from supporters of tradition to supporters of innovation (conservatives and liberals, respectively, to use phrases that are common in the modern United States), with many possible positions in between the two. The conflict resulting from political diversity is often debilitating and occasionally even bloody. Still, if you accept that your political views are imbued less with majestic rationality than primal biology, that they bubble up from within rather than get passed down from on high, and if you recognize that predispositions affect how people perceive, process, and experience the world, you will have learned something valuable not just about yourself but about.

Notes