5

Looking at Your Family Tree

When I meet new patients, my recommendations for their treatment are based on much more than just their appearance. I always ask my patients about their ancestry as far back as they know, and specifically where their maternal and paternal grandparents are from. In our global society, borders are melting. We live in a world of mixed ancestry. A green-eyed redhead with pale, freckled skin might have an ancestor from Portugal, Spain, or Morocco with a dark complexion. An African American might have a Swedish grandmother with pale skin and hair. The amount of pigmentation in the skin is not necessarily an accurate reflection of genetic ancestry. Fair skin can behave like dark skin, and dark skin can react like light skin depending on your genetic makeup. The complexity of skin types is far more than meets the eye. Look around at your family reunion, study an old family album, and talk to your relatives. Your blood relatives may exhibit a broad spectrum of skin tones. You may have forgotten or never known that your British great-grandmother married an East Indian, but you could be carrying genes for darker skin.

I had my revelation about the importance of understanding a patient’s ethnic origins back in 1997. I was attending a national conference in Boston, where one panel featured prominent, highly respected dermatologists talking about poor outcomes from resurfacing techniques. I listened to my colleagues review complications from simple laser procedures. They reported that some patients had inexplicably developed second-and third-degree burns from laser or chemical treatments that had left other patients with exemplary results. An unlucky few were in the burn unit for months, requiring hyperbaric oxygen to heal their burns and reconstructive work to repair their skin.

Just as pigmentation or the color of skin is inherited, the way wounds heal, even the controlled injury of laser treatment, is determined by genetics. We know that what works for Northern European blue-eyed blondes might not necessarily be an effective treatment for darker-complected people of African, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, Asian, East Indian, or American Indian descent. Thinking about my clinical observations, it occurred to me that without knowing patients’ ancestry, we could subject them to treatments with unpredictable outcomes that might damage their skin.

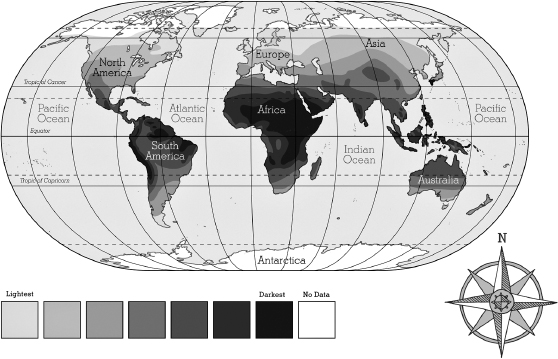

On the flight home, I had finished my reading and pulled the in-air magazine from the seat pocket to flip through. I stopped at the map of the world showing the routes the airline flew, which I studied. As I did, I thought about dividing up the world in terms of geographic global ancestry. The name of the country is not important, but the global geographic location is. The map of geographic skin pigmentation I envisioned is on the next page.

There seem to be as many skin tones as there are people—the variation is that broad. Skin color and hair color are created by the amount, type, and packaging of the pigment melanin, all of which are determined genetically. We know little about the genetic basis of pigmentation. Rather than a specific skin color gene, many genes work together to produce your skin tone. Ethnic skin coloration has a lot to do with geography and evolution. Skin variations in ethnicity differ not only in color but also in skin components, including collagen, elastin, blood vessels, lymphatics, nerve fiber, glandular components, immunity, and reactivity. No precise standard exists! Treatment approach requires caution… always.

LIFE UNDER THE SUN

Different skin tones developed as adaptations to geography and the sun’s ultraviolet rays. As you already know, melanin has an important physiological role in protecting the skin from sun damage. The closer our ancient ancestors were to the equator, the more melanin was needed to protect their skin.

Ultraviolet rays help the body use vitamin D to absorb the calcium needed for strong bones, but too much exposure to ultraviolet rays can strip away folate, a nutrient essential for fetal development. Skin pigment developed as the body’s way of balancing the need for vitamin D and the need for folate. Darker skin evolved close to the equator to prevent folate deficiency. The cardinal rule is that evolution favors reproductive success. When groups migrated farther from the equator where ultraviolet rays are lower, natural selection favored lighter skin to allow enough vitamin-D-forming UV rays to penetrate. Today pigmentation varies within geographic regions, but there is still a strong correlation between the strength of the sun’s UV rays and skin pigmentation.

WHY DARKER SKIN LOOKS YOUNGER LONGER THAN FAIR SKIN AND OTHER ETHNIC DIFFERENCES

Your pigmentation depends on the quantity and quality of melanin in your skin, the amount of UV exposure you have, and genetics. Melanin is the natural skin pigment that protects skin cells from UV rays. Melanocytes produce melanin, which is packaged in melanosomes—found mostly in the basal level—to protect the germinating epidermal cells from UV damage. Though concentrated in the basal layer, melanosomes are dispersed throughout the epidermis. More melanosomes are concentrated in the epidermis of the head and forearms than the rest of the body. Everyone has approximately the same number of epidermal melanosomes, but their size and distribution differ with ethnicity and different shades of skin. The melanosomes in darkly pigmented skin are larger and more individually dispersed compared with other skin tones. In fairer-skinned people, the melanosomes are smaller and are grouped in complexes of two or more. The most lightly pigmented types have about half as much melanin as skin that is darkly pigmented, leaving fair skin more vulnerable to the damaging effects of sunlight.

Since melanin is built-in SPF (sun protection factor), skin pigmentation dictates skin changes associated with photo-aging. More darkly pigmented skin begins to show signs of aging later than lightly pigmented skin. Though fair complexions tend to wrinkle and sag earlier, darkly pigmented skin can become mottled, hyperpigmented, hypopigmented, or generally uneven in tone when injured or inflamed.

Some researchers have found that on average the darkest skin tones contain more corneocyte layers in the stratum corneum than the fairest skin, though there is no difference in the thickness of the layers. The cell layers are more compact in the darkest skin, which creates greater cohesion among the cells. This compressed architecture of the stratum corneum strengthens the barrier function in darker skin. Very dark skin tends to have larger pores and greater sebum secretion.

THE LANCER ETHNICITY SCALE

Thomas Fitzpatrick, one of my professors at Harvard, developed what is now known as the Fitzpatrick Classification Skin Typing System, which has become the standard method for defining skin pigmentation. He was measuring the skin’s ability to tolerate light or UV rays to find the correct dose of UVA for the treatment of psoriasis. He had six skin types: very fair, fair, light golden, olive, brown, and dark brown.

I wanted to build on his concepts of phototype by including heritage as part of the definition. The Lancer Ethnicity Scale, based on geography and heredity, is summarized in the following chart:

The Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES)

| ETHNIC BACKGROUND | LES TYPE |

|---|---|

| African Background | |

| Central, East, West African | V |

| Eritrean and Ethiopian | V |

| North African, Middle East Arabic | V |

| Sephardic Jews | IV |

| Asian Background | |

| Chinese, K orean, Japanese, Thai, Vietnamese | IV |

| Filipino, Polynesian | IV |

| European Background | |

| European Jews | III |

| Celtic | I |

| Central, Eastern European | II |

| Nordic | I |

| Northern European | I–II |

| Southern European, Mediterranean | III–IV |

| Central/South American Background | |

| Central/South American Indian | IV |

| North American Background | |

| Native American (includes Inuit) | III |

There is a simple formula for finding your LES skin type. Just add up the numbers that correspond to your grandparents’ ethnicities and divide by four. The higher your score is, the more likely you will experience complications with healing after a cosmetic procedure. A high number indicates you might have an adverse reaction to aggressive resurfacing procedures, including laser treatments and chemical peels. If there is healing involved, there is risk. Once you calculate your LES skin type, the chart that follows lists the level of risk of an adverse reaction to a resurfacing procedure.

| LES SKIN TYPE | RISK |

|---|---|

| LES I | Very low |

| LES II | Low |

| LES III | Moderate |

| LES IV | Significant |

| LES V | Considerable |

Though I developed the Lancer Ethnicity Scale to predict complications from procedures, the scale can be applied to skin care as well. The LES types provide a green-, yellow-, or red-light approach to treating the skin, whether with topicals or procedures. Depending on your type, your skin will react differently to skin care products. Let me explain.

- LES I or II: These types do not get a free pass. Though hyperpigmentation is not a huge problem, fair skin requires gentle care. Not only is fair skin susceptible to sun damage, but it can be highly sensitive and reactive. Dryness and rosacea can be problems. Blood vessels can become hyperactive, resulting in instability. This tendency to be reactive is why I am including a chapter on caring for sensitive skin to avoid premature aging. Of course, sensitivity occurs in all skin types. When skin is hyper-reactive, you have to introduce new products gradually. People with this level of skin pigmentation begin to polish and use anti-aging products gradually to avoid irritating their skin.

- LES II or III: These types are deceptive. Skin with this level of pigmentation does not burn quickly, but does develop wrinkles and sagging. LES IIs and IIIs can scar easily, and discoloration can take years to improve. When lightening chemicals quiet a hyperpigmentation reaction, the pigment cells can go dead with this type. The rebound is to less pigmentation or hypopigmentation, which produces white zones. Skin with this level of pigmentation might have to be eased into polishing, because the transportation of signals from the stratum corneum can be aggressive and result in hyperpigmentation.

- LES III or IV: Olive-colored skin has to be treated with extreme caution. This skin tone might age slowly, but can easily become inflamed. Olive skin has relatively small pores. The combination of small pores and hyperactive oil glands can lead to acne. Type III or IV skin can discolor with blemishing. People of these skin types can develop dark circles around their eyes. Sometimes skin pigmented at this level only partially responds to color correction. Chapter 7 will present a program for acne-prone or blemished skin.

- LES V: Black skin, like all other skin types, has great variability. It can be extremely sensitive. If you are not trained to observe the signs, you can miss a reaction. LES V skin can be so sensitive that it becomes severely inflamed in response to even minor irritations. The pigment can become uneven, resulting in hyperpigmentation (increased color) or hypopigmentation (decreased color). Capillaries can become visible, and eyelid folds can become rough. Other common texture changes include scarring—particularly keloids, or raised scars—and depressions in the surface of the skin called pits or divots. Certain ingredients in acne medications or anti-aging products can leave a white or gray film on darkly pigmented skin or lead to inflammation. Special care has to be taken with topicals. The chapters that follow on acne, sensitive skin, and advanced anti-aging will include information of particular interest for people of color.

The following chapter takes the basic Lancer Anti-Aging Method to another level of healing and renewal. For some of you, the basic three-step program will be all you need to refresh your skin. If you have been doing the basic Lancer Anti-Aging Method for three to six months and want to do more to stimulate your skin’s repair mechanism, you might be ready for the Lancer Advanced Anti-Aging Method. Remember, Lancer Rule Number 1 is not to rush anything. Change takes time.