GRAND UNION AS LABORATORY

Each Grand Union dancer entered into the improvisational fray with different instincts, and they all exited Grand Union with a different cache of tools. During those six years, they were also making their own work and thus became even stronger in their own diverging directions. It’s hard to tell which playground influenced which. However, it’s clear that Grand Union was a catalyst and instigator for continued work: Steve developed Contact Improvisation; Barbara started her Contemplative Dance Practice; Douglas had never choreographed until a GU “rehearsal” at which only one other person showed up; Trisha first expressed her wish for dancers to “line up” during Grand Union; Nancy brought her newfound improvisational talents to her work with musicians; and David got a clue about how to make a group dance, not to mention that his playwriting ability sprouted during those years. What they all shared in Grand Union and carried forth into their separate lives as choreographers was a strong sense of play.

The clearest, most nameable development emerging from Union labor was Contact Improvisation. As part of the 1972 Oberlin residency, Paxton’s afternoon workshop yielded Magnesium. A short piece with risky tumbling, bumping, lifting, and rolling, it was infused with an egalitarian air, a democracy of roles. Steve was expanding what he and others were already doing in Grand Union: “I think one of the first Contact Improvisation moments that I noticed in Grand Union I had done with Barbara in certain duets, but they just felt like regular male/female duets. But with Doug, there was a long duet that we did in which we took each other’s weight … and I recognized that we were doing it by touch, not by how it looked or what kind of set-up might be expected.”1

Steve felt compelled to explore this form further. He didn’t want it to go the way of all improvisation—to disappear.2 One of his ideas for Grand Union went directly into Magnesium:

Something that I scored for the Grand Union led to Contact Improvisation. It was a solo on a mat that started off low, rolling and stretching thru the legs, and ended up high, with leaping rolls and catches Basically it was an investigation of the body in space where the feet didn’t have to be on the ground…. It was the place where I went through the basic perceptual stuff, peripheral vision, horizon change, the kind of stretching that makes rolling and falling easy … having established a form in which the head doesn’t have to be upright, what new way of seeing the world does that entail? The world just goes whirling around your eyes, and you have to find other sources of stability—momentum and sense of gravity are the major ones.3

He continued to develop his idea after Oberlin while teaching at Bennington, where it became more of a duet form. Once he named the form and debuted it in SoHo in June 1972, it spread like wildfire, attracting both dancers and nondancers. Nancy Stark Smith launched the journal Contact Quarterly to explore the ramifications of this growing phenomenon. Contact is now practiced on every continent except Antarctica, and annual festivals in cities from Freiburg to Buenos Aires attract hundreds of people.4 Steve credits Grand Union with nurturing the movement language that went into Contact Improvisation: “The vision of Contact Improvisation was in part provoked by the constant flowing forms we encountered when Grand Union was cooking. Grand Union provided a constantly changing view of possibilities of form, performance, space, audience. A perception of flux.”5

Although the Oberlin residency was a key part of the launching pad, Paxton also drew on previous influences like aikido, the Living Theatre, Forti’s dance constructions (particularly the centrality of touch), the early choreography of Trisha Brown and Carolee Schneemann at Judson, working with Rainer on CP-AD, and his own past as a gymnast. Grand Union was a laboratory not only for the physical discoveries of Contact Improvisation, but also for how to talk about it. Catterson’s log of the 1971 loft performances notes: “Steve gave a lecture on falling down, curving down, and rolling—despite all of his elaborate descriptions he didn’t demonstrate for the longest time. The suspense was hysterical!”6

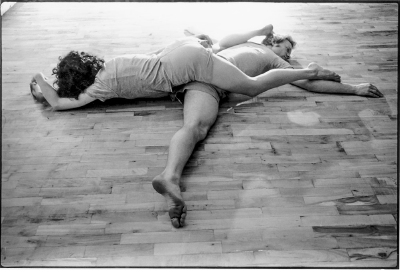

GU at LoGiudice, 1972. Steve Paxton arching over Brown. Photo: Gordon Mumma.

Stark Smith enjoyed the predawn sessions at Oberlin so much that she told Steve she wanted to be included in the next iteration of Magnesium. Paxton readily accepted that the male-female barrier could be breached. When he invited students from Oberlin, Bennington, and University of Rochester to live and work together for ten days before the first performance at the John Weber Gallery, he was taking the communal aspect of Grand Union a step further. According to Stark Smith’s memory, “We kind of lived in the midst of whatever it was that was beginning to take effect, because we spent so much of the day rolling around and being disoriented and touching each other and giving weight.”7

Contact Improvisation wipes away assumptions about gender and other hierarchies. In a 2016 interview with Stark Smith, Steve talked about “aligning” one’s own Small Dance with that of another person. The result, he said, is a duet of two “followers” rather than one leading the other. “In between the two people, a third thing arrives.”8 This faith that something will spring up out of what may look like passivity is inherent in Grand Union’s ethos.

Being against hierarchies of all types, Steve is reluctant to be considered the “leader.” When addressing the Contact Improvisation practitioners at an anniversary gathering in 2008, he said, “[M]y job was to make up a way to teach it. I had felt the form in my own body and I wanted to find a way to express it to you guys. And I think you had all felt it in your bodies. But anyway, I couldn’t progress without collaboration. It’s a mutual form.”9

After ten years, Steve left the Contact Improvisation fold to work on his own. His abdication of the leadership role in some way parallels Rainer’s stepping down as choreographer of CP-AD. As Nancy Stark Smith said, “He framed this work; he gave us tools, and then he stepped aside so that the individuals could really discover something.”10

∎

From her work with Grand Union and other experiences, Barbara developed Contemplative Dance Practice, which she taught at Naropa University (formerly Naropa Institute) in Boulder for decades. The elements of Grand Union that contributed to Contemplative Dance Practice were these overlapping ideas: being in the moment, simplicity, sticking with one thing, and honoring the possibility of “group mind.”

For Dilley, investing in the present was something she learned on the job, as it were, in Grand Union. “That combination of demand and fluidity in those Grand Union shows … to not be strategizing about anything, not to figure out anything in the past or future … [meant] you had to work with what was happening right in front of you.”11

Dilley’s line of inquiry was more about how dance fits into life than how it fits onto a stage. When she performed her Wonder Dances at the Walker Art Center in 1975, dancer/choreographer/critic Linda Shapiro wrote, “Because for her dancing is a process inseparable from the life process, her performance is more an intimate rite than a public display.”12 These intimate rites eventually involved meditation, and it was the intertwining of dance and meditation that formed the basis of Dilley’s Contemplative Dance Practice. This includes the “little disciplines” of slow motion, stillness, repetition, and imitation. All are modes that naturally seeped into GU performances. Both Grand Union and her Contemplative Dance Practice formed an “open space for observation.” The mystical side of her furnishes this as an aside: “The ancients find places on the land favorable for receiving messages from the unseen.”13

One of her “intimate rites” was a solo I saw in 1971 titled Dancing Before the Beloved (Dervish). Spinning was all she did, and flowers (on the crown of her head, waist, wrists, and ankles) were all she wore. Sitting on the floor in a circle around her, we waited for a single candle to be passed around so that we could each use it to light the candle placed in front of us. The performance was an opportunity to meditate on time passing, the continuity of one revolving body, and the nature of ritual.14

In her teaching, Barbara favored ideas of great simplicity. She named “five basic moves”: standing, walking, turning, arm gestures, and crawling. She channeled these actions into “corridors” or “grids,” structures that make the performer aware of space and the contagion of movement.15 She introduced a form of Follow the Leader using peripheral vision. This was one of the ideas she tried out on Grand Union members—until it was determined that none of them wanted to do her Follow the Leader or Steve’s Small Dance or anyone else’s ideas. However, her Follow the Leader score evolved into Herding and Flocking, which she introduced in the Natural History of the American Dancer. These structures, she wrote, were “about locating collective mindbody and playing together.”16

Sometimes being in the moment means resisting rather than going with an impulse. Dilley said that Grand Union “taught me both how to trust my impulses and also how to stick with material, which is the other end of the spectrum. Impulse is extremely seductive.” She felt that Trisha, in particular, set an example for focusing intently on the activity at hand.17

The “group mind” that Dilley sensed in Grand Union is something she sought to replicate in the Natural History.18 She also wanted to create an environment in her teaching that was conducive to group mind, “with insight and absurdity.”19 I duly note that during the group interview, both Douglas and David objected to the term “group mind,” suspecting that it ignores people’s individuality. (Steve had no objection to it; he has used the term himself.) But Barbara’s definition—“a wild, deep play that coaxes the ensemble to cross over into that under-consciousness”—does allow for individuality.20

Barbara was a sensual dancer, and at the same time very spiritual. I think GU gave her the space to work toward bringing body and mind together, and that is one of the deep pleasures of watching the Grand Union videos.

∎

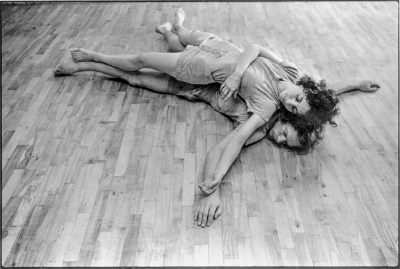

Douglas hadn’t choreographed before Grand Union and had no plans to go that route. But one day he showed up for a GU rehearsal and nothing happened—and then something happened: “Barbara and I arrived on time, and nobody else arrived. We were sitting there … and wondering why people weren’t arriving…. [F]inally I said … ‘Do you want to do something?’ She said, ‘OK, sure.’ So I said, ‘I’m gonna lie down on my front here with my arms and my legs out, and why don’t you just sit on me. And then after a while see if you can change your position without touching the floor.’”21

His first concert, titled “One Thing Leads to Another” (1971), was a shared evening with his then romantic partner Sara Rudner at Laura Dean’s loft in SoHo. They each made bits for both of them to perform. He gave Rudner, a dancer of divine lucidity who was in Twyla Tharp’s early company, the task he had worked out with Barbara during that underpopulated rehearsal. She would sit on his back for two-and-a-half-minute segments. “She would set [the clock] and take a position and it would go bing! And she would reset it and take a new position…. I was a dead man.”22

Like Steve, Douglas enjoyed stillness both for its contrast with movement and as an activity in itself. Critic Marcia B. Siegel described a moment at La MaMa in 1975 when Dunn stood in one place, moving only his mouth and his eyebrows.23 Douglas took stillness even further when he made the remarkable installation 101 (1974). He built an edifice of three hundred wooden beams that filled his SoHo loft, top to bottom, side to side. You could climb through it until you arrived at a lightbulb near the ceiling. Under that fixture lay Douglas, strapped to horizontal beams, his hands and feet bound as though he were a sacrificial lamb. He was even more of a “dead man” than in his piece with Rudner. This “installation performance” was open to viewers four hours a day for seven weeks. Douglas was testing how far he could take stillness.24 Part of his purpose was to rebound from all the movement-movement-movement he was immersed in with Merce Cunningham’s company.

Douglas Dunn with Sara Rudner in rehearsal for “One Thing Leads to Another,” 1971. This duet started in a GU rehearsal with Dilley. Photo: Robert Alexander Papers, Special Collections, New York University.

Douglas’s ability to transform a performance space continued in Grand Union. At UCLA’s Royce Hall in 1976, he felt the theater was so much larger than GU’s usual intimate spaces that he decided he needed to do something to connect the stage with the audience. So he stretched a string from the proscenium to the balcony so the audience could feel a “symbolic connection.”25 And there was, as mentioned in chapter 6, that time he built a bridge to fill up the visual and aural space.

Another way to change the space is to disrupt the edges. At Seibu Theater in Tokyo, Douglas backed into the black traveler curtain that framed the central figure who was, at that moment, David. Douglas danced with the drapery, advancing and retreating, toward and away from David. He was playing with the physical as well as the metaphorical border between onstage and offstage.

Once Douglas caught the choreography bug, he kept experimenting. During the Grand Union years alone, he made or co-made about fourteen works. Although he is currently interested in making dances rather than improvising, he admits that “the tremendous openness about who I could be and what I could do”26 in GU has given him a wellspring of fortitude.

∎

Trisha was the most experienced choreographer in the group (other than Rainer) as well as the most experienced improviser (including Rainer). So in a way she had less need for a laboratory. She’d already had a lab, and it was called SoHo. She had explored task, gravity, resistance to gravity, and the body in the environment. But Grand Union was about interacting with other performers. In this realm, I would say, she investigated four aspects that she incorporated into later work: talking while dancing, “lining up” and recall, highly inventive partnering, and deploying large objects.

Talking while dancing is one of the reasons she agreed to join Grand Union. She was curious about how she might implement words in her own way. In early Grand Union sessions, she made sure she practiced talking and also encouraged David in his talking. Regarding the first GU rehearsal Trisha came to, David wrote (again, referring to himself in the third person): “Trisha dances and talks about a house with many floors. David dances’n talks—and adds floors to her house—and her story—and adds laughing. His laughing morphs into crying’n he keeps talking. Trisha—having got interested in talking—gets more interested in talking and moving—and working with David.”27

Trisha had already slipped a quiet, functional kind of talking into her late sixties pieces. In task dances like Leaning Duets I and II (1970 and 1971), a dancer might say to her partner, “I need you to give me more leeway here” or “Can you twist this way?” With “Sticks” (part of Structured Pieces I, 1973), which became a section of Line Up that I performed many times, we had to alert the others whenever the tip of our stick lost contact with the woman’s stick adjacent to us. I might say, “Mona, I’m off,” in which case we would all hold still while I managed to get the end of my stick to touch hers again, and then I would say “I’m on” so that we could resume the task. This kind of verbal keeping track accompanied the many instances of Trisha and Barbara’s gymnastic grapplings in Grand Union.

But another kind of talking—telling stories, with David being the prime perpetrator—may have given Trisha the impetus she needed to embark on the solo that became Accumulation + Talking + Water Motor. She made this piece in stages, “upping the ante” with each new addition. In the final version, she spliced two different stories into two different solos: Standing Accumulation and Water Motor (1978). When she performed this piece, you could see she relished the physical and mental challenges, which have been nicely captured in Jonathan Demme’s 1986 film, Accumulation With Talking Plus Water Motor.

Another Grand Union ploy that carried over to Trisha’s work was carting people around as though they were objects. In one LoGiudice video, David and Trisha first confer, then lift and relocate three of the other dancers, one at a time. Whether it was Douglas or Barbara or Yvonne, the person stayed still or continued what she or he was doing. This kind of carrying the body as an object went into Group Primary Accumulations (1973). In this piece, four women on the ground accumulate thirty movements (as in 1; 1,2; 1,2,3; and so on) in unison and keep the movement going as two people start lifting and moving them to a different location. It’s as though they are mechanical dolls that have been wound up and can’t stop. In the early performances of Group Primary, the two movers were David and Douglas. It was a role they knew well.

When I was dancing with Trisha, we were immersed in the process of making Line Up for a year. At the time, I didn’t know the main idea had antecedents in GU. In one LoGiudice video there’s a scene in which David and Barbara are playing out their attraction/aggression toward each other with giddy volatility, and the others line up a few feet away and watch them. What followed was a rerun, a mode that GU members could hop into at any moment. David retold “what just happened” as Barbara stepped out of a line to help him. During the hubbub of that particular re-run, Barbara said, “Well, we were here. David says I was back here.” Yvonne said, “I went like that,” motioning David to come to where she was. David said to Trisha, “You took a step forward.” Trisha said, “You took a tentative step forward. I took a large one. Steve, you took a little tiny baby step and I went far ahead of you.” This was exactly the kind of exchange we had in Trisha Brown’s company during the recalling phase of the building process of Line Up (1977)—discussing and dissecting what just happened, in detail. (See the interlude after this chapter for a more complete memory of Line Up.)

Steve told me recently that Trisha deliberately tested the idea during those early days of Grand Union: “She first articulated Line Up in a Grand Union rehearsal. We tried it out desultorily, but she tried it out later on her own company. That seemed to express the tension in the relation between GU and her proper choreography, to me. With the gift of her first company, she had a chance to herd those cats.”28

I was one of those cats who was happily herded by Trisha in the years after she exited Grand Union.29 Of course, what we did while “lining up” was not exactly being herded but engaging in a project of turning improvisation into choreography.

In their early gymnastic forays, Trisha and Barbara sometimes involved Nancy. Catterson reports that as early as 1971, the three teamed up to do handstands: “Their bodies became intertwined, limbs supporting others’ limbs, a continual precarious balance with each delicately making shifts of the limbs.”30 It was this kind of thing—sculptural shape-shifting, though with much greater inventiveness—that showed up in Brown’s works during and after GU. This rich vein culminated in the “pitch and catch” section of Newark (Niweweorce) (1987), in which the dancers created interlocking, moving architecture, initiated from surprising points of connection.31

Two physical objects that have surfaced in Trisha’s choreography also gained her attention in Grand Union: the foam mattress and the ladder. Pamplona Stones (1974), the spare, elegantly goofy duet she choreographed with Sylvia Palacios Whitman, made whimsical use of a very large piece of foam. At one point, the foam plank gets curved in such a way that it hides parts of the two women’s bodies, creating the illusion that one very wide woman is sitting behind it, hugging the sides of the foam. This bespeaks Trisha’s love of illusion as well as her wit and humor. Back in Grand Union’s loft performances, Catterson noted that Barbara and Trisha used a “huge piece of foam rubber as a sitting cushion, a backpack, a slide, and a hammock with the two chairs.”32 Sounds to me like it could have been the seed for a section of Pamplona Stones.

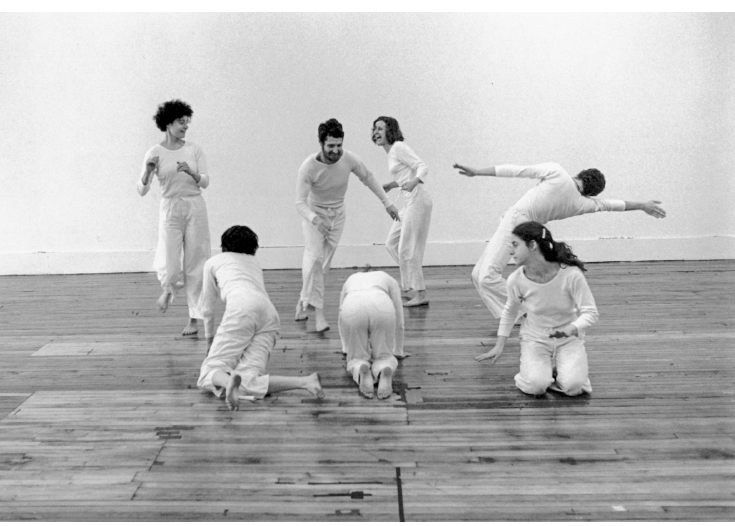

Trisha loved climbing. In Grand Union she climbed on ladders, hung on two-by-fours, and walked atop a ballet barre. It’s part of the same love of disorientation that gave us Walking on the Wall (1971). To elucidate only one of those examples: at La MaMa in 1975, a ladder was brought in by Barbara and Steve. Steve lay on his back, raised his legs in a not-quite shoulder stand, and balanced the bottom of the ladder on the soles of his feet. Trisha impulsively dove partly through the rungs of the ladder, thought better of it, then started climbing it, with Barbara and Douglas girding her. Steve lowered his pelvis to the floor, the better to give Trisha a foothold, and made suggestions from his position on his back. She climbed high enough to get her hands on the top rung, to much applause.

This love of climbing found its way into several of her later works, including El Trilogy (2000), with music by jazz composer Dave Douglas. In one section Diane Madden, who has been dancer, rehearsal director, and co-associate director of the company, improvised with an eight-foot ladder. “We had a little bit of a structure,” Madden told me. “The first half or so was me wearing the ladder, and the second half was me climbing on it.”33 At times the ladder ended up wrapped around her neck, prompting Trisha to dub it “the ladder necklace.” For Madden, a contact improviser before beginning to dance with Trisha in 1980, a big part of the process was the dialogue that went along with the one-on-one rehearsals. Her account reveals Trisha’s continuing interest in improvisation:

GU at La MaMa, 1975. Brown on ladder, Paxton on ground, Dunn and Dilley (mostly hidden). Photo: Babette Mangolte.

When I was improvising, she kept asking me, “What are you doing? How are you making your choices?” It was a lot about the process—or the act—of listening … listening to my movement and those questions of Where am I and what can I do from this place? In dealing with an eight-foot ladder, whether you’re wearing it or climbing on it, that’s a key process: Where am I, where is the ladder, feeling it, and then from that place making a compositional choice. Also listening to the phrasing where there’s a balance of action and stillness. And, because of how striking the ladder is visually, allowing for something to have time to be seen … allowing something to have a life. And then also listening to the sound of the ladder—it was a noisy thing—and also listening to the sound of the music…. The Dave Douglas band was improvising.34

Trisha felt the need to balance out the general mayhem of Grand Union with something supremely simple. Her Accumulation series achieved that. When I was on tour with Trisha, she once told me that while performing Group Primary Accumulation, “I’m thinking, This is all there is.” Very different from the everything-at-once commotion of Grand Union. In fact, as she told Rainer: “[I]n counterbalance to the Grand Union and all of that extreme pain and pleasure that comes from letting it all hang out, I was doing my own work. The Accumulations were very carefully organized, each gesture, however absurd, meticulously studied.”35

∎

Nancy Lewis was more of a performer than a choreographer. She shone during a performance, whether it was set or improvised. Perhaps to emphasize that she had no ambitions to choreograph, she called her 1971 solo concert at The Cubiculo “Just Dancing.” It included works by Rainer, Gordon, Paxton, Jack Moore, and Remy Charlip.36 The solo by David Gordon, Statue of Liberty, was originally part of Sleep Walking at Oberlin. She also added her own improvisation with a pianist playing live. “Someone was playing the piano, kind of classical modern piano, and I just danced and ended up on a high note. My legs and arms went up and that was it.”37

She earned a rave review from Don McDonagh in the New York Times: “Rich, unforced and admiring laughter was the background to Nancy Green’s concert, Just Dancing.” He called her rendition of Rainer’s Three Satie Spoons (1961) a “strikingly good revival.38 I saw it at The Cubiculo and I agree; she had the right irony, delicacy, and strength for that disciplined yet loony solo. Her solo concert at the Walker as part of the 1971 residency was positively reviewed by critic Linda Shapiro, who wrote that Lewis “projects a glamour which is both juicy and deadpan.39

In her interview with Sally Banes, Nancy was forthright about the problem of originality. She said that while working in the studio, she would catch herself bounding into the air as Steve would do or talking in a repetitive rhythm like David would do, and she would think, “Oh no, this is not original.40 But that did not put a dent in her dancing, which she continued doing until the eighties.

∎

For David, the edict to improvise eventually freed him from the judgment of executing a particular phrase correctly. What began as a crutch in Grand Union performances, namely the sequence of Rainer’s Trio A, could eventually be left behind while he put his own imagination into play. “When I was onstage dancing in Trio A … I was extremely self-conscious. I was aware of being watched and possibly being graded in relation to the material and anybody else. In the Grand Union that all went away…. I became the person who it was possible to invent and do and respond to anything because there was no thing that was the perfect thing I should have been doing.”41

Once he lost his inhibitions, David could further explore concepts that served him later: first, what he called “double reality”; second, assuming a character; third, a way to develop group work; and last, how to turn an abstract event into a story.

David first participated in an example of “double reality” (which also might be called “self-commentary”) during a pre–CP-AD performance of Rainer’s group at Pratt that contained a seed of Grand Union. This was not planned, but a happenstance that bubbled up from the loose structure. “At some point there was a discussion about the thing we were doing and whether we were doing it right, and it was an audible discussion. It had to do with the section in which everybody stood in a circle and somebody fell and you had to get caught. You wanted it to be a surprise but you didn’t want to get hurt. What was the intention, and now we were talking about it, and people were laughing and listening to us talk about the thing we were doing. That, for me, was a changing point.”42 This kind of self-commentary showed up in many of David’s later works.

The character element came with generous dollops of campiness. In the Walker Lobby performance of 1975, he was a smooth-talking emcee in a TV contestant show, and at La MaMa, also in 1975, he was an arrogant pasha auditioning dancers. The double reality popped up often in David’s later work, for instance, in Not Necessarily Recognizable Objectives (or Wordsworth Rides Again) (1978), in which David and Valda have a very lifelike argument, and it’s not until they switch roles—or you’re close enough to see the script posted on the wall—that you realize this was totally planned.

In the sixties at Judson, David had made only solos and duets; he had no idea how to approach group work. During Grand Union’s early loft performances, he initially refused to join the others in improvising. The breakthrough came after he visited Steve in the hospital and came away with the “I’m slipping” scene described in chapter 7. When two of the other dancers echoed his words and movement, he felt he had found a way forward: “Suddenly it’s like the arrow in a sign [that] shows you a direction to go in. They were framing me in a way which amplified what I was doing, and the amplification came back to me to do something about.”43

Another factor that edged David toward group choreography was that during that same period, Yvonne asked David to somehow keep her group of students together while she was in India. His admission years later: “The thing that was more horrible to me than making work was teaching.”44 So instead of giving a class, he worked on a piece for the students. One of them was Pat Catterson, who included this experience in the log about Grand Union she kept in order to show Rainer upon her return. About the first rehearsal with David, she wrote: “We did a sleeping thing leaning against the wall. Then standing up, nodding off, attempting gestures in our sleep such as scratching, grabbing, adjusting, rubbing our face, and so on. We did this for ninety minutes!”45 This was the beginning of Sleep Walking, which was first done at a loft on 13th Street in February 1971 and then, in different versions, at later residencies.

At Oberlin he made The Matter, which passed through many versions in the ensuing years. It’s a large group piece that incorporates many stillnesses. In the April 1972 version, the performers and audience filed in together to the Merce Cunningham studio in Westbeth Artists’ Housing. Scattered among the clothed performers were a random few (including Valda) who were nude. The mix of professionals, students, and nondancers allowed, within David’s structures, a certain amount of individual freedom.46 It’s ironic that The Matter was such a community piece, because David claims he never felt a desire for what he called the “communal, let’s-all-work-together” ethic of either Judson or the Grand Union.47

By May 1972 David had developed his narrative abilities, gathering more voices than just his own, basically writing a theatrical scene on the spot. The way David describes this achievement is that he was translating the physical or conceptual explorations of his colleagues into a narrative: “I almost always framed with a gesture or sound or word something that turned the circumstance out of the spectacularly abstract way that Trisha and Steve could work and made it literal. It’s all I could add; I couldn’t add beautiful movement to what they did. I could add the circumstance in which it was happening.”48

Applying this ability to his later works, he said, “I think ninety percent of the time in my entire career, that’s what I do: I turn what seems like a physical movement relationship between two people into something happening between two people.”

∎

Yvonne left Grand Union—and dance—in 1972 to make films. Although she was entering a different medium, she brought her love of performers and performance with her. But film is an entirely different discipline, so there is not much I can say about GU being a laboratory for her future work. However, I have two examples. The first is from In the College, her work for Oberlin students. The final series of tableaux vivantes, based on the still shots of G. W. Pabst’s 1929 film Pandora’s Box, was something she also brought to the ending of Lives of Performers. The second example is only a hunch. One of the striking moments of her Film About a Woman Who … (1974) is when the cam era zooms in on Yvonne’s face, to which she has attached little pieces of paper with messages written on them. After seeing the video of the incident mentioned in chapter 16, when Trisha stuck a piece of paper to her forehead, I think it’s possible that Yvonne got the idea from that moment. However, Yvonne was always looking for ways to incorporate written messages into performance and film. That was true in her earliest works at Judson, and it’s true of her return to choreography in the last twenty years.

DANCING WITH TRISHA

I had seen Trisha Brown’s work in a gallery space, and I loved the sense of mischief between the women performers. But the concert that has imprinted on my memory was at the Whitney Museum in 1971. Three of the pieces blew my mind: Walking on the Wall, so disorienting that it was practically hallucinatory; Falling Duet I with Barbara Dilley, as recklessly risk-taking as if they had been doing tricks on a high wire;1 and Skymap, in which we, the audience, lay on our backs, looking up and following Trisha’s words on tape while we beamed our imaginations up to the ceiling.

In a haphazard way, I let Trisha know I wanted to dance with her. Twice I ran into her on the street and expressed my interest. No response. Then, waiting in the checkout line at the grocery store—it was, no kidding, the Grand Union on LaGuardia Place—I found myself standing next to her. I was surprised that she knew my name. She asked me what I was doing these days. “I’m dancing with Sara Rudner and Kenneth King,” I replied, “but I’m going to stop soon and just do my own work.” Luckily, she ignored my answer and invited me to come to a rehearsal in her loft. That was November 1975. I found out later that one of the reasons she had asked me was that she knew I had studied with Elaine Summers, founder of “the great ball work,” aka kinetic awareness, and an ally of Trisha’s since the Judson days.

The beginning of my three years with Trisha overlapped with the end of her five years with Grand Union. When I came to the studio in November 1975, we first worked on making our own movement to fit into a highly complex accumulating and deaccumulating scheme. That was Pyramid. During the same period she was building the long “Solo Olos” phrase that would go into the larger work Line Up (1976).

When Trisha told us to “line up,” I didn’t know what she meant. But I quickly caught on. She meant: What does a line mean to you—and to your body? She meant she likes to see straight lines but she also likes messing them up. She meant she wanted to know what lines we could make between the walls and radiator and pipes and each other. Could it mean lining up our energy, could it mean being swept up into a big circular run? Could a perimeter be a line? She wanted to see a range of interpretations.

We created the main part of Line Up through a process of improvisation and recall. We would improvise on the instruction to “line up” for about ten seconds, then we’d go back and reconstruct what we thought we had just done. Trisha would step out and look at several segments strung together—which wasn’t easy because she was in the piece and all our decisions were interdependent. Then she would keep the segment, or fiddle with it, or rip it up. We accumulated these bits over a year to make the fabric of an hour-long piece into which Trisha inserted a number of organized “line dances” she had made before.

For the final version of Line Up, we had set our improvisation in choreography, if not in stone. It was not easy for the audience to decipher any pattern in the main lining up sections. Those long sections appeared as chaos compared to the short, inserted line dances like “Sticks,” “Spanish Dance,” “Eights,” and “Scallops.” The line dances were easy on the eyes, creating a contrast with the less orderly parts that we made through improvisation. New York Times critic Anna Kisselgoff complained that “[a] middle section appears too long and does not make clear to the audience what the dancers’ tasks are.”2 For us, it was about lines appearing and disappearing, relationships forming and dissolving. As with Grand Union, what one of us chose to do affected all of us.

In the making process, we had to be super conscious of each other. While improvising and recalling our actions, we were reconstructing memory, with the other women’s bodies as our signposts. We had to realize, again and again, that the person next to us remembered something different in time, space, and gesture. The claim, “Wait, you were on this side of me and your shoulder was here,” would be met with “No, my right shoulder was in line with Elizabeth’s ear.” Or, “I saw a gap from across the room and was making a line to bridge the gap.” That process of going from thinking we remembered correctly to realizing we had it skewed was appealing to Trisha. She wanted to retain that rough-around-the-edges quality instead of polishing it to a sheen.

At one point, she built in a fleeting “surprise moment.” We would pause, and then one of us would leap or flutter or spin or crumble, before we all moved on with the dance. Just anticipating that moment of guessing changes your mental makeup. Who will make the surprise move? Will I be the one? Can I delight or confound my peers with three, action-filled seconds?

Rehearsal for Trisha Brown’s Line Up (1976), Trisha Brown studio. Standing, from left: Wendy Perron, Paxton (guest artist), Brown, Terry O’Reilly (guest artist). On floor, from left: Elizabeth Garren, Mona Sulzman, Judith Ragir. Photo: Babette Mangolte.

Trisha took that unknowingness further. We tried to actually create a new segment in front of the audience. Like Yvonne in CP-AD, Trisha wanted to expose the making process—that was part of the art for her. I now see that attempt as a continuation of Grand Union’s practice of revealing process.

While I was watching the Tokyo video from December 1975, the overlap between my starting to dance with Trisha and her last performance with Grand Union was brought home to me. Toward the end of the performance, Trisha stood up to perform “Solo Olos,” the very movement phrase she was teaching us back in New York. The intricate sequence is danced forward and backward—hence the title.3 It was rare for anyone in Grand Union to perform a set work. In the early days, David Gordon ran through all his permutations of Trio A, and Yvonne slipped parts of her first solo, Three Satie Spoons (1961), into the mix at Oberlin when she was off to the side of the stage. But here was Trisha, performing this current transplant from her studio, center stage, as a soloist.

In the Tokyo video, after Trisha finishes “Solo Olos,” the other dancers taunt each other to perform a solo while Trisha stretches out on the floor downstage to watch. Steve delivers a remarkable rendition of it, capturing the steady rhythm, the eccentric openings and closings, the brushing of the hand against the floor, the flat back while lowering the body to the ground. When Barbara gets up to do a solo, she doesn’t try to emulate “Solo Olos.” Instead, she lopes around the space, then zeroes in on a more rooted dance while Steve tells a story about Barbara’s favorite birds. Expecting to be next in line to dance a solo, David feels put on the spot. He takes his feelings of insecurity—after all, he would be compared to Trisha, Steve, and Barbara—and transforms them into a grandiose act. He sings/wails a song of mock despair (“Do you know what it’s li-i-i-k-e”), strutting and crouching like a rock star.

Watching this video of the Tokyo performance, I realized two things: first, that in a more direct way than I had thought, I was linked to the tail end of Grand Union, and second, that in some way Trisha had already left Grand Union.