Ah, the lawn. . .that rolling expanse of green, every blade identical and perfect, not a dandelion in sight. Do you hold this vision of perfection in mind when you picture your home? You’re not alone, of course. In North American landscaping, the lawn is often the focal point. The United States and Canada are unique in their communities of large expanses of lawn. Other continents lean more toward gardens, enclosed patios, pastures, forests, with perhaps a small patch of grassy green. But in Canada and the U.S., the lawn’s the thing. Stand-up comedians do routines on lawn obsession. Sitcoms devote episodes to the drive to attain the perfect lawn, or at least a better one than your neighbors. In real life, homeowners’ associations sometimes go so far as to mandate the quality of all lawns in their communities.

Without a doubt, a well-kept lawn is attractive, an asset to your home and neighborhood. It provides room to romp and feels good under bare feet and paws. It can also suck up mega-gallons of water, encourage liberal application of toxic herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers, and burn up gallons of gasoline for mowing and trimming, not to mention have environmental impacts. It doesn’t have to. A more natural lawn-care regime has less impact on the environment and your pets.

Some of those obsessed with the perfect lawn insist that dogs are not compatible with a lawn. Given their idea of what a lawn should be, perhaps they’re right, but in this dog-loving gardener’s mind, their priorities are surely misguided. No lawn has ever greeted anyone with a happy-to-see-you wagging tail, and lawn care is more likely to raise blood pressure than lower it. (Pets have been shown to have a beneficial impact on human health, lowering heartrate and blood pressure, increasing chance of survival after a heart attack, and more.)

I maintain that lawns and dogs are meant to go together. Yes, there can be problems, both for the lawns and the pets, but they can be overcome. The solutions often benefit not just the household dog, but the lawn, and the environment in general.

So take a deep breath, stop obsessing, and read on. You can have an enticing sweep of greenery without endangering your dog, devoting all your spare time to the lawn, or spending all your spare cash.

Just What Is a Lawn for Anyway?

Think about it a minute. What are your reasons for wanting as big, as perfect, a lawn as you do?

Oddly enough, some people respond that they need this large magnificent sweep of lawn for their pets. Dog owners point out that their canines appreciate the room to romp, and they use the lawn to play Frisbee or ball games. While playing with your pet is a fantastic way to spend your time, it isn’t justification for lawn obsession. Your dog does not care if dandelions rear their yellow heads, and may actually prefer some grass-like weeds to grass itself. Clover feels just as good under the paws, too. Dogs certainly enjoy open space, but they just don’t care much about what grows there, as long as it isn’t stickers or burrs.

Lawns make great play areas, but perfection isn’t necessary.

Open space is one thing and a “perfect” lawn is another. Lawns are good play surfaces—certainly better than the expanse of rock seen in the now-common alternative of xeriscaping (water-sparing gardening)—but you need to keep things in perspective. Who decided that little clover blossoms are unsightly in a lawn? Those not concerned with lawn “perfection” may, in fact, find this more attractive than a uniform green, and clover is valuable for fixing nitrogen in the soil. It may also attract rabbits to nibble on your lawn rather than your vegetable garden.

Take a moment to consider just how much lawn you really need, too. Lawns are fairly water and care intensive, and you don’t want all that fuss and expense without good reason. If you have one area for the dog, another for the kids, and yet another for outdoor dining, that’s fine. Just know why you want the lawn that you do.

A lawn should be for enjoyment!

Choosing a Lawn Wisely

Whether you’re sodding using plugs, or seeding, you have a wide variety of choices in lawns and lawn alternatives. Some work better with dogs than others. Making a wise selection will minimize future problems. Consider your climate, the use you will put your lawn to, how much care and water you plan to devote to it, how much sun and shade space it will occupy, and of course, how well it stands up to wear and tear. Understand that a good choice of grass will get you off to a good start, but keeping a lawn healthy is your best bet for minimizing any canine damage to it.

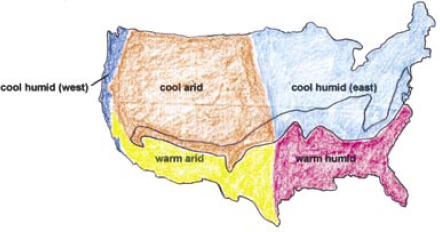

Before choosing what grass you will install, if starting fresh, or use for re-seeding, if doing a patch job, consult the lawn temperature zone map. Roughly the southern third of the United States, from coast to coast, is classed as warm weather—the eastern half of this southern third is warm humid and the western half is warm arid. The northern two-thirds is cool weather, the eastern half and strip along the west coast being humid and the rest arid. If you aren’t sure what area you live in, any local nurseryperson or Master Gardener should be able to tell you.

Lawn temperature zones. Areas between cool and warm are transition zones.

Lawn Temperature Zones and Grass Types (*-less *****-most suitable)

For dog-owning gardeners in warm-weather lawn zones, Zoysiagrass receives the highest recommendation for home lawn use. Its wear resistance is exceptional, standing up to heavy traffic. It loves sun and tolerates partial shade. A number of varieties are available, with differences in growth rates and shade tolerance.

If your lawn area lies completely in the sun, Bermudagrass is also a good choice. It features a deep root system, stands up well to traffic, and recovers rapidly from any damage. But it cannot tolerate shade, and simply won’t grow under trees. Like all the warm-weather grasses, it goes dormant if temperatures drop below 55 degrees, but can take extreme heat in stride while requiring relatively little irrigation.

Centipedegrass, often recommended for shady locations, is not a good choice for lawns that will bear a lot of foot or paw traffic—it doesn’t stand up well to wear. St. Augustinegrass comes in shade-tolerant varieties and is at least moderately resistant to wear. Tall fescue, though classed as a warm-weather grass, is gaining popularity in some of the warm-weather zones because of its tolerance for shade and ability to survive cooler weather and stay green throughout the winter. It also offers the bonus of being more resistant to high concentrations of nitrogen—the culprit in yellow lawn spots from dog urine—than any of the other grass varieties.

A couple of native grasses are becoming popular for their low-maintenance requirements. Though they won’t provide that lush emerald green look, they will give you more time to spend with the dog rather than mowing. Buffalo-grass will grow well in the sun, even under conditions of severe drought, and will stop at a height of four to five inches, without any mowing. Another native being sold under the name of Turleturf (see www.turleturf.com) shares similar characteristics.

For lawns in the cool-weather zones, Kentucky bluegrass has long been a favorite for its rich color. Because we’re concerned more about how the lawn will get along with the dog, the fact that bluegrass can take only moderate wear is a drawback. It will not do well at all in shade or in dry conditions. To counter these problems, bluegrass seed is often blended with other varieties, such as perennial ryegrass or fescue.

Ryegrass can withstand a bit more traffic, especially in its rapid-growth phases in the spring and fall. Fescue comes in “fine” and “tall” varieties. The fine is so named because its blades are extremely thin and non-succulent, a property that makes them resistant to both injury and drought. It can be left unmown for a natural meadow look. Tall fescue puts out the deepest, most extensive root system of all the cool-weather grasses, and so can withstand drought and recover from injury. Tall fescue and ryegrass both offer the bonus of resisting high nitrogen concentrations found in dog urine, so will not be as prone to developing yellow spots.

For play areas in public parks in cool-weather zones, improved Kentucky bluegrass mixed with a relatively high percentage of improved perennial rye-grass is most often recommended for best resistance to wear. So it will stand up to your dog reasonably well.

Many, many books have been written on the subject of lawns. Refer to them or the excellent Better Lawn & Turf Institute website (www.lawninstitute.com) for more detailed information on what to look for in lawn seed and sod.

Installing a Lawn

Many people are intimidated by the thought of installing sod. The Turf Resource Center advises, “If you can understand ‘Green Side Up,’ you can successfully install sod.” It is manual labor—rolls of sod aren’t light—but not mentally taxing. Here is just a quick course.

While sod is far more expensive than seed, it provides a lawn without the wait. Keep the dog in mind when you make your installation plans—you need to leave an area for the dog to romp and potty on during the three weeks the sod will need to root. Don’t sod your entire yard at once unless you plan on taking your dog for many walks every day.

Soil preparation is critical to effective sod installation. Don’t take shortcuts in preparing the soil, and then blame the dog when your lawn doesn’t grow thick and rich. For best growth, grass needs sunlight, air, water, and nutrients. Everything but sunlight is obtained from the soil. These essentials are best provided by loams or loam and sand, with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0. Compacted soils and clay soils make it hard for roots to grow and collect nutrients. Extremely sandy soils can’t retain water and nutrients for any length of time. For a healthy lawn, soil should be improved to a depth of six inches. A lawn cannot be healthy without good roots. So don’t skimp on preparing the soil, as follows:

1. Clear the new lawn location of any rocks, stumps, building materials, debris of any kind—any foreign object larger than 2 inches across.

2. Grade the area so the surface is even and either level or gently sloped. Make sure it slopes away from any building foundations, and that no slope is too extreme.

3. Till at least the top two inches. This will help the topsoil you are going to add adhere to the native soil, take care of any compaction, and help prevent annual weeds.

4. Add topsoil so that the total till depth is at least six inches after rolling. If you can, add humus (the proper term for fully decomposed organic matter) to the topsoil during this process. Be aware that manure and humus may be attractive to your dog—be prepared to keep the dog away.

5. Test the soil pH and amend as necessary. A number below 6 can be raised through the addition of lime, and a number above 7 can be lowered through the addition of gypsum or sulfur. Ask a local professional for amounts to use.

6. Work a fertilizer high in phosphate (the middle of the three numbers found on most fertilizers) well into the soil. This can be an organic fertilizer—it doesn’t have to be chemical.

7. Grade the entire area to be sodded and roll it with a lawn roller one-third full of water. Apply irrigation and look for any low spots that collect puddles. Bring them up to grade.

With this preparation, your sod should take hold quickly and provide a lush, low-maintenance lawn.

Be prepared to start installing sod immediately upon its delivery. Remember, turfgrass is a living thing—it can survive only for a limited time without water and contact with the soil. It will be easiest for you if you have the turf placed in stacks around the area to be covered so that you don’t have to carry rolls farther than necessary. If it will take you more than half an hour to lay all the sod, the waiting piles should be shaded and wet down to keep them healthy.

Prepare the soil well, unroll the sod, butt strips frmly together and stagger ends, and water. That’s all there is to it.

Lay the first strip along a long straight line such as a driveway. Push the edges of strips frmly against each other. Space the joints as if you were laying bricks (see photo).

Trim as necessary with a sharp knife. Try to avoid small pieces of turf at the edges because they will dry out too quickly. As much as possible, avoid walking or kneeling on the turf as it is being laid.

Once turf is laid, roll the whole area to make sure it has good contact with the soil, then water a minimum of one inch. Water at least daily, more often if necessary to keep turf moist, for at least two weeks. By then the turf should be rooted and you can begin to water less frequently. Keep foot traffic—human and dog—off the new lawn for three weeks.

If you are using seed rather than sod, weed control becomes more of an issue because seed will take time to establish itself. Tilling will largely control annual weeds, but perennial weeds can survive tilling and still prosper. A post-emergent herbicide needs to be applied to the soil several days before tilling (this is one of the few instances where a chemical herbicide is appropriate). The sequence is:

1. Apply the post-emergent herbicide. Wait several days. (Keep the dog off the area once herbicide is applied.)

2. Test the soil and amend as necessary, with lime or gypsum or sulfur as needed, and with a high-phosphate fertilizer.

3. Till the soil four to six inches deep to work in the soil amendments and prepare the soil for the next steps. Rake to remove any rocks and debris and to contour the area.

4. Apply the seed, following package directions.

5. Water daily, or twice daily if weather is hot, but not deeply. Grass seed should be kept moist but not drowned until it sprouts. Once it begins to grow and establish a root system, too much water can promote disease. Water less frequently but more deeply. After four to six weeks, treat as an established lawn, applying at least an inch of water when the soil is dry to the depth it was tilled.

6. Once the lawn has grown to a height about one-third higher than the recommended height of your grass variety, mow for the first time. Mowing frequently will tend to help a seeded lawn thicken and prosper.

7. Control any weeds that may appear by hand weeding. Do not use herbicides on a seeded lawn for at least a year or you will kill your tender new grass along with the weeds.

Caring for an Established Lawn

There are two basic philosophies of caring for a lawn—the traditional way, incorporating chemical herbicides, insecticides, and fertilizers on a regular basis, and the organic way, relying on maintenance practices to keep the grass healthy, adding organic additives when necessary. This chapter will take a look at both. Be forewarned that I am not among the “perfect lawn” crowd. Whatever grows that’s green and soft underfoot is just fine with me, and dandelions are a delicacy for my sheep. I don’t use chemicals of any sort on my lawn. That means I don’t have to worry about the dogs, I can let the sheep out to do the mowing for me, and yes, my lawn contains various shades of green and can sometimes be patchy. That’s my choice. Even if you care a bit more about your lawn than I do, you still have the choice between traditional and organic.

Start by considering that according to the Earth Works Group, homeowners use as much as ten times more toxic chemicals per acre than do farmers, with the average household applying five to ten pounds of pesticides to the lawn each year. Steve Hansen, DVM and Veterinary Toxicologist at the ASPCA National Animal Poison Control Center, notes that most homeowners tend to over apply lawn chemicals, some to a great degree. Obviously, this greatly increases toxicity. Where chemicals are concerned, more is not better. Over fertilization can, in fact, kill a lawn. Overuse of herbicides and pesticides can result in runoff, with these chemicals entering lakes, streams, and the groundwater aquifer. Even correct usage of lawn chemicals can affect beneficial earthworms and microbes, friends of gardens who improve soils and lawns by breaking down organic materials that otherwise would contribute to thatch.

TRADITIONAL LAWN CARE

Whether you do it yourself or hire a lawn care service, traditional lawn care requires caution. A lawn care service should provide advance warning of when they will be coming and what products they will be using. All pets (and humans) should be kept off sprayed lawns at least until they are completely dry, preferably for a full day. After twenty-four hours, the grass has bound the chemical to itself and only one percent could possibly be dislodged. Dogs who have a habit of eating grass should not be left to nibble on any treated lawns, even after 24 hours.

Because many of the chemicals routinely used in lawn care are also used in pet care as flea preventatives, knowing what is applied to your premises is important. While the organophosphate sprayed on the lawn (known by names such as chlorpyrifos or Dursban) may not be enough to cause harm in itself, the same substance can be found in flea dips, flea sprays, and flea collars. Together, several products might add up to a toxic level. You might want to look into non-toxic flea control products.

ChemLawn™, the largest lawn treatment company in North America, states that if an animal is in the yard when one of their employees arrives to apply a treatment, the yard is not treated. Beware if your dogs have access to the yard through a dog door—they might stay inside until after the treatment is applied, then venture out while the lawn is still wet with chemicals. You need to keep them away from treated areas.

Amazingly, some homeowners will let their dogs follow them around while they put down granular products such as the popular fertilizer/herbicide combinations (Scott® Weed and Feed or Preen and Green®, for example). Those granules are just sitting on the grass until watered in, and can easily stick to paws and fur. Pets should definitely not be allowed until the lawn has been watered well. Not only are chemical herbicides a potential hazard to your dog, if the dog walks through weed killer and then across the lawn, you may end up with a series of little dead spots where the dog (with weed killer on his paws) walked. Indoors, the chemicals on his paws may stain your carpet. If your pet somehow does wander into a freshly treated area, a bath in water and dish detergent will wash off any chemical residue.

More than half the lawns in the United States are at least seven years old. They could benefit from some overseeding, and the newer improved varieties of lawn grasses offer better tolerance to drought and greater resistance to disease and insects. Overseeding lets you keep much of your old lawn while improving its appearance and upkeep requirements. Such renovation is best done in early spring or fall. (See books or websites devoted to lawn for specific recommendations in overseeding. I’ll just note here that several dog owners have put down seed, covered it with a thin layer of straw, continued to let the dog run through it at will, and succeeded in sprouting the seed and growing grass.)

ORGANIC LAWN CARE

Organic lawn care relies on proper watering and mowing to keep the grass in good health and growing vigorously. Most lawn care specialists will tell you that weeds appear when a lawn is in less than top health, and killing them with herbicides will cover up the symptom without solving the underlying problem. Organic gardening relies on correcting basic problems rather than masking them with chemical “cures.” It’s kinder to pets, humans, and the environment in general. Though it may seem more trouble and expense in the short run, over the long haul it can actually save you time and money.

Susan Cruver of Tsunami Landscape Design advises liberal use of compost on lawns. “Lawns receiving a yearly top dressing of compost (1/2 to 1 inch, best applied in early spring) and regular applications of compost tea fare much better against all sorts of dog abuse, both chemical and physical. Dog pee is processed well, with less occurrence of yellow spots. The turf will have longer, better-developed roots and will better resist dog traffic damage. The compost/compost tea duo will help any part of the landscape hold up better to dogs.”

LAWN MOWING ADVICE

Many homeowners let lawns grow too long before mowing, and then mow too short. This may allow you to mow less frequently, but it’s not good for your lawn’s health. The rule of thumb advised by the Better Lawn & Turf Institute is never remove more than one-third of the leaf surface when mowing. (Leaf surface, also called cutting height, is the portion of the grass above ground.) Cutting too short also lets the ground heat up and dry out more easily.

As with all power equipment, keep lawn mowers serviced and running smoothly and, most importantly, keep blades sharp so they cut rather than tear the lawn. Mow when it’s dry, and let the clippings fall where they may. They provide a natural fertilizer and mulch. If you are in the market for a new mower, consider a mulching mower for even better results—they simply chop the clippings into smaller pieces and blow them down into the lawn.

Keep the dog safely away from you and the machine while mowing. Even hand mowers can kick up rocks unexpectedly, and power mowers can fling them at great velocity. Avoid any chance of injury by keeping the dog inside while you mow.

WATERING ADVICE

Proper watering is essential to a healthy lawn. The object is to water infrequently but deeply to encourage good root growth. Frequent shallow watering will result in poor root development and a lawn susceptible to pests, disease, and dog damage. An average lawn needs one inch of water a week. Remember to take precipitation into account. An inch will soak the lawn to a depth of four to six inches, the depth of the grass root zone.

The Lawn Institute offers some guidelines on how long it will take to deliver one inch of water to various soil types.

| SOIL TYPE | TIME REQUIRED FOR 1 INCH OF WATER TO SOAK IN | |

| sand | 1/2 hour | |

| sandy loam | 1 hour | |

| loam | 2 hours | |

| silt loam | 2-1/4 hours | |

| clay loam | 3-1/3 hours | |

| clay | 5 hours | |

The sophistication of your irrigation equipment doesn’t matter—a computer-timed pop-up system and a whirligig sprinkler on the end of a hose can both deliver efficient water if used properly. The key is to check the coverage and amount of water you are delivering.

For best results assess your irrigation to really know how much water you’re delivering to an area.

For parts of the country that don’t receive rain in the summer, you might consider letting some of the lawn go dormant. In many climates it doesn’t harm the lawn—especially if you water once a month through the dry season—and it saves watering and mowing all summer long. Check with local experts before doing this and always keep high-use areas green and avoid heavy traffic in sections you allow to go dormant.

If you still feel that you need to use lawn additives, you have organic products available. Websites such as Gardens Alive and many others specialize in organic alternatives. You can buy all-natural organic fertilizers for use on new or established lawns, parasitic nematodes to conquer problems with grubs and other lawn pests, and even a “weed-and-feed” organic product that contains a natural lawn fertilizer and an organic pre-emergent weed control. As Gardens Alive points out, “No need to post warning signs on your lawn, no fears about having your children and pets play in the grass.”

For more detailed information on organic lawn care, consult the websites listed in the Resources, your local Master Gardeners, or buy one of the many books available, such as Building a Healthy Lawn.

YELLOW SPOTS

See Chapter 9 for advice on training your dog to use the potty area of your choice, and you’ll avoid dead yellow spots in your lawn from the excess of nitrogen in dog urine. If after you’ve trained the dog to use his potty area some yellow spots still appear, don’t be too quick to blame your dog for breaking training. If your yard is unfenced and open to the neighborhood, other dogs may be wandering in and leaving their calling card. Not only can they damage the lawn if they drop by frequently, they can entice your own dog to urinate in the same spot to overmark their scent.

The lawns in England are generally smaller and not so lush and green as American homeowners seem to desire.

There is also a lawn disease called fairy ring that looks remarkably similar to dog urine damage—it often has the same dead circular areas surrounded by darker green grass. It’s caused by a soil fungus, and has nothing to do with the dog. You will often find what looks like mushrooms in the lush ring of grass. They are the “fruit” of the fungus, and some are poisonous. Because the fungi feed on organic matter, removing thatch, aerating the lawn, and removing leaves or tree stumps may help avoid or resolve the problem. Using tree spikes (fertilizer in the form of pointed stakes that you press or pound into the ground) to water around the edge of the ring to a depth of one to two feet can also curb the problem. Until a circle of mushrooms appears (which doesn’t always happen), fairy ring is difficult to tell from dog urine spots by visual examination. If you dig into the spot and find a thick white substance, it’s fairy ring.

Finally, please don’t believe what you may hear about certain foods or supplements changing the dog’s urine so it doesn’t damage lawns. While giving your dog tomato juice or salt may encourage the dog to drink more, thus diluting the urine, the dog will need to urinate more frequently as well. The salts in these “remedies” may create heart problems, while fruit juices and baking soda (another frequent recommendation) increase the risk of bladder stones. The only safe, reliable methods of slightly reducing urine nitrogen are to feed a highly digestible dog food (not a bargain brand), which lets the dog digest more of the protein, resulting in lower nitrogen, and to wet dry food with water.

A study by a Colorado veterinarian, Dr. A. Allard, has shown that watering the spot even up to eight hours after urination is effective. It dilutes the nitrogen enough for it to be an acceptable fertilizer. Because you can’t water the entire lawn every eight hours, you need to be there to observe when and where the dog has peed.

Lawn Alternatives

No other groundcover can stand up to the amount of wear and tear a lawn can take. But for lesser-traveled sections of the yard, slopes that need to be covered to prevent erosion, and other particular circumstances, you can choose among other low-growing plants. Some can even tolerate dog urine better than turf-grass can.

Lilyturf can tolerate a fair amount of foot traffic without complaint. It needs only a once-yearly mowing and not a lot of water. The creeping variety (Liriope spicata) spreads by underground rhizomes, while the clumping variety (Liriope muscari) doesn’t spread but does flower. The creeping variety fills in readily to cover any temporary damage from urine.

Pachysandra (also known as spurge) has long been a popular groundcover. Homeowner use has largely focused on readily available Japanese spurge, but other varieties offer more interest, with a native American variety (P. procumbens) providing a brighter green that shows fall color and P. Kingwood offering a more delicate ground covering. And there are others.

Clover can provide a dense ground cover whose flowers attract bees. It would be a good choice in an orchard setting, away from the dog’s everyday yard. Bees and dogs don’t make a good combination.

A slow-growing plant, but one that will eventually cover the ground in evergreen foliage, is barren strawberry (Waldsteinia ternata). It can accept sun or shade, and not only flowers in spring, but provides a stylish purple-bronze fall color.

Chapter 3 looks at some other groundcovers in a section by that name. Of course there’s always the non-plant alternative. Kathy Burkholder notes that “The dogs’ urine left big dead spots in the grass, which then turned to a muddy mess in the winter. I’ve replaced all the grass with mulch, and have landscaped the perimeter of the yard to add a little more green.”