Access—or, Why Can’t I Get This?

There is no question that we are in a time of great flux in the publishing world. The well-established and mutually beneficial relationships between publishers and libraries have changed. Some of these relationships are reaching their breaking points as journal and online database prices increase, and the licensing of e-book content threatens to render irrelevant copyright law’s exhaust rule, which allows purchasers of copyrighted materials to dispose of them as they see fit (lend, resell, or discard). Access has the potential to become universal, but barriers—for better or for worse—still exist that prevent 100 percent fully open and sharable content. In examining open access the discussion shifts from one about online open access journals to the more specific needs of e-books and monographs. This chapter explores the issues of content access in MDLs and some of the finer points of open access, including the gold, green, and platinum open access models.

The Open Access Philosophy and How It Applies to MDLs

Ask any librarian how he or she feels about databases and you’re likely to get a mixed answer. An unbelievable amount of content is available for users, they’ll say, but the costs of journals have skyrocketed into the tens of thousands of dollars per title. The economic drain is palpable and unsustainable. Harvard University Library, one of the premier research libraries in the United States, if not the world, recently stated that the situation was unsustainable, even for its impressive budget.1

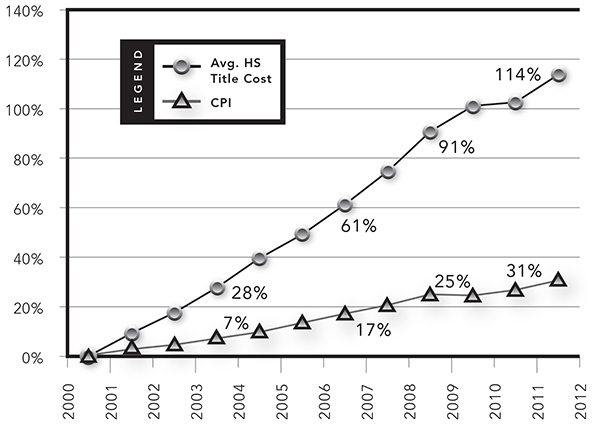

Figure 8.1

Costs of journals by discipline in comparison to Consumer Price Index.

(Courtesy of University of California San Francisco Library)

What has caused this situation? On the one hand, the publishers appear to be practicing ruinous price gouging by greatly outpacing the Consumer Price Index during the decade of the 2000s (see figure 8.1). Libraries expend far greater amounts of money on online journals than ever before, and prices continue to rise. Yet more people have more access to more information than ever before. In fact, when looking at the number of downloads per user or downloads per article versus overall costs, the cost-per-use ratios may not be so ruinous, especially if the ratios translate to a few dollars per article. Libraries may sometime be getting their money’s worth, even if that initial sticker shock can be hard to handle.2 What is missing in figure 8.1 is how many users have accessed these materials—it’s likely that the number of users has grown along with the price.

Yet some of the issues raised earlier in this book regarding the destruction of the middle class via the advent of the Internet and some of its impact on destabilizing established markets are also at play here. There is a real chance that many small to midsize publishers, especially university presses, will be driven out of business because of the open distribution and piracy of published content. Larger publishers are also seeing a drop in profits, even though they still turn profits.

One current solution to the issue has been to implement open access as a policy for libraries, publishers, and universities. There are two main types of open access: gold and green. These types of open access, while linked by commonly held beliefs, approach the problem of access to content in slightly different ways.

Gold Open Access

Gold open access—or the so-called gold road to open access—or simply Gold OA, refers to those journals that publish peer-reviewed articles without paid subscription barriers for their readers. However, this does not mean that costs do not exist. Instead, costs are transferred to authors via article processing charges (APCs). The APCs are paid by authors, their parent institutions, or related grant-funding agencies. The process works to a surprisingly successful degree. Some of the most prominent journals in various disciplines are gold OA journals, including the Public Library of Science, ArXiv, Annals of Family Medicine, Duke Law Review, and more (Grumpenberger, Ovalle-Perandones, and Gorraiz 2013). Such gold OA journals have become the standard for their respective disciplines. Nevertheless, the financial burdens fall upon faculty or scholars, who may not necessarily have the funds to cover the APCs. In some cases APCs are exceedingly expensive—several thousands of dollars per article to pay for perpetual open access. These fee scales are sometimes unaffordable for authors or institutions reined in by smaller budgets.

Green Open Access

As a result of some of the financial issues regarding gold open access, green open access (or green OA) attempts to gather the earlier versions of works that have already been published. Most university institutional repositories collect the preprint, print, and draft versions of the content created by their own faculty. The narrower scope—usually just focusing on the journal publications of individual faculty aligned with a university—affords a little more flexibility from publishers. In some cases, the green OA repository arose because online databases have priced out libraries and universities from accessing the very scholarship funded by them. It is seen, then, as a way for libraries to guarantee perpetual access to their institutions’ own scholarship by circumventing the paywalls constructed by proprietary interests that also often have the original author’s copyrights transferred to them as well.

Outcomes and Results of Open Access

Some publishers have been compliant with open access, but many have not. As a result, two sides have formed. One side is strongly in favor of open access; the other is just as strongly against open access. As Vincent and Wickham (2013) write, “The position that open access is ethically necessary and/or inevitable, and the position that it has so many practical problems attached to it that it risks being pointlessly destructive unless they are resolved, each seem the obvious starting-point to substantial groups of researchers.” The two sides essentially do not take into account the validity of the other side’s points.

The result of this lack of compromise is an escalating cycle in which one side continually increases prices to the point that only the richest can afford the service and/or content, whereas the ones that are priced out have to find content elsewhere. Those stuck in the middle wind up having to seek out more open access materials, settle for inferior products, drop other materials, or resort to various workarounds. As Gardner (2013) writes, “Learned societies suddenly found themselves caught, largely powerless, in the crossfire of a battle between an evangelical RCUK/Wellcome Foundation [an OA group] and the commercial publishers over rising costs and profits.”

However, even if open access is contributing to some of the issue of rising costs, the only existing safety valve to the issue of rising journal and subscription access costs is open access. If enough major organizations and governing bodies join the movement, publishers will have to compromise on their often draconian approaches to academic scholarly communication.

MDLs and Open Access Books: Bridge or Chasm?

The overall discussion of open access focuses mostly on journal publication. However, as table 8.1 shows, books are still an essential part of scholarly communication in certain disciplines. Open access, as a result of its intense focus on journals, has less of an impact on such disciplines, mostly in the humanities and social sciences.

In some ways, monographs are a difficult beast: they “blur the boundary between specialist academic publications and what publishers call the general or trade list” (Vincent 2013). As a result, many special concessions made by journal editors, learned societies, and their publishers might not apply. Open access journals tend to be for limited audiences. However, monographs are often written and published with a wider audience in mind. As a result, there is much more revenue at stake with monograph titles than with journal articles. The potential for loss is much greater in terms of costs of labor, printing, and marketing such books. Providing open access books is much more problematic.

Table 8.1

Breakdown of publication types by discipline

|

Discipline |

Books |

Chapters |

Journal articles |

Other |

|

English |

39 |

27 |

31 |

3 |

|

History |

40 |

22 |

37 |

1 |

|

French |

37 |

23 |

39 |

1 |

|

Philosophy |

14 |

20 |

65 |

1 |

|

Sociology |

22 |

10 |

64 |

3 |

|

Law |

18 |

15 |

65 |

1 |

|

Politics |

29 |

9 |

62 |

0 |

|

Economics |

1 |

2 |

89 |

7 |

|

Chemistry |

0 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

Source: Vincent (2013).

There are some strategies, however, that have been developed to help improve open access for books. In each of these solutions it might be possible for MDLs to play a large role in the development of such OA texts.

The first strategy involves posting books as PDFs on a website. This is not unlike what happens currently with scholarly articles. Faculty in certain science, technology, engineering and mathematics disciplines often post copies of their papers on personal websites. A similar action might be taken by authors of monographs interested in allowing their content to be accessible to anyone. Some institutions already allow access to long white papers, reports, and even published book-length documents (Vincent 2013). This type of model has become known as the platinum model of open access, in which OA publishing fees are charged to neither the author nor the reader. Instead, consortia work together to provide the economic sustainability to absorb costs. Some examples of these include Open Book Publishers and Knowledge Unlatched (Vincent 2013).

How might an MDL be incorporated into such a scheme? In many ways, the sheer size of MDLs predispose them to being very helpful for such publications. Users would be drawn by the sheer numbers of items already within the collection, much as they are already drawn to Google Search. As we have seen, MDLs also have consortia partners built into their collections. HathiTrust and Google Books have dozens of institutional partners each. The power of their cooperative forces could be gathered to create and support such platinum OA endeavors. Advertising revenue generated in the case of Google Books would alone support the publishing costs of the endeavor.

The second strategy would be to mimic the process of gold OA by charging authors or their funding institutions article-processing fees, but on a larger scale. In this case the APCs would range in the tens of thousands of dollars rather than a few hundred to several thousand dollars. MDLs would be able to provide records, a solid searchable system, and name recognition in order to improve the overall accessibility of the work.

Finally, the green open access strategy would work in ways similar to the current institutional repositories that collect the preprints, postprints, and occasional final versions of scholarly institutional-related papers. It would be easy enough to upload the drafted versions of a book into, for example, a DSpace system. As with many repositories, multiple versions of a document can be stored in a single record. This would allow users to access the information without the same formatting.

However, one issue with a green OA repository of e-books and monographs will be deciding upon an industry-standard period of embargo. Currently, many publishers of scholarly articles require embargoes of twelve to twenty-four months. This may prove much too short of a time for book-length subject treatments. It may be that a period of five to ten years would be sufficient for a publisher to receive enough revenue to support the endeavor. Beyond ten years would likely be an unreasonable amount of time, as the marketability of most copyrighted materials declines quickly (Schruers 2013). The 2003 case Eldred v. Ashcroft examined the constitutionality of the Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA); the case cited a study of books examined that held renewed copyrights prior to the 1998 CTEA investigations, and only 11 percent had any commercial value.3 Beyond a certain period of time, it appears that most books will not have any economic benefit for the copyright owners. The key is to find that sweet spot of how long to market the work for the maximum economic benefit and when to allow it to be freed from embargo.

It may be that MDLs can help with managing such embargo periods. Placing an item in the HathiTrust, for example—itself a highly searchable system with robust metadata—would also allow its author to have automated embargo terms or to limit users who have to authenticate to access the content. The HathiTrust already provides greater access to content for its members than to at-large users. Perhaps if a monograph or book were offered online as part of a university class, the class members might have limited access to it during the time when the book is embargoed.

MDLs’ Strategies to Provide and Limit Access

As described in the previous chapter on copyright, materials falling in the public domain are fully accessible. However, because of the lawsuits brought forth by the Authors Guild and others, MDLs will provide only limited access to works still operating under copyright law. As a result, most of the books in MDL collections are kept behind access walls. This section examines how Google Books, the HathiTrust, Europeana, and the Open Library limit access to digital books restricted by copyright. Although the Internet Archive doesn’t upload books that are copyright protected, its access layout is worth examining and so is included in this chapter.

Google Books

Google Books controls access to the digital books in its MDL using the following four levels: record only, snippet view, partial view, and full view. Record-only view provides only the most basic metadata for a book and no possibility of seeing the text, in much the same way that libraries or OCLC’s WorldCat do with their integrated library system online catalogs.

The information about the book itself includes as a minimum the following metadata elements in the order they appear in the online user interface:

• Title

• Author

• Edition (if applicable)

• Publisher

• ISBN (if applicable)

• Original from (source of the original book, such as New York Public Library)

• Digitized (date)

• Length (number of pages)

• Subjects (if applicable, selected from BISAC subjects)

Records also include the thumbnails of related books; table of contents: QR codes; customer reviews; star ratings; and links to citation manager software solutions such as BibTeX, EndNote, and RefMan. The record-only view is likely an indication that a book has not been placed into Google Books’ digital corpus of books.

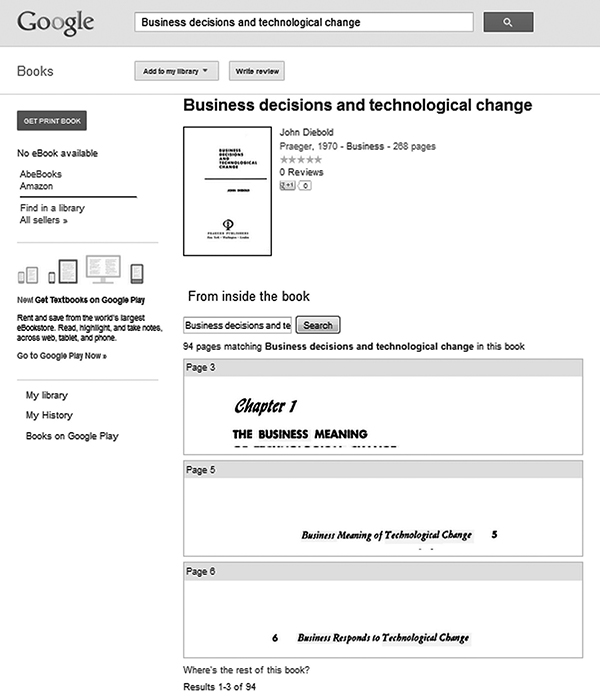

Along with this basic metadata, the higher levels of access—snippet, preview, and full text—provide varying levels of access to the digital text. The snippet view includes small boxes of text roughly two inches in length from top to bottom by five inches in width. As shown in figure 8.2, these snippets include a few sentences of the text along with queried keywords.

Figure 8.2

Google snippet view, which includes boxes that provide a few sentence or words of highlighted text.

One can search the full text of the book and receive small segments of it to aid in research or other endeavors. However, Google is also careful to provide an explanation to users as to why the access is limited for the book. The text question “Where’s the rest of this book?”, which appears under a hyperlink, takes users to a page explaining access policies.

Google’s policy is twofold. If an author is a Google partner, then the author is the one choosing the level of access. If an author is not a partner, then Google provides only a record or a snippet view. The policy states, “The aim of Google Books is to help you discover books and assist you with buying them or finding a copy at a local library. It’s like going to a bookstore and browsing—with a Google twist.”4

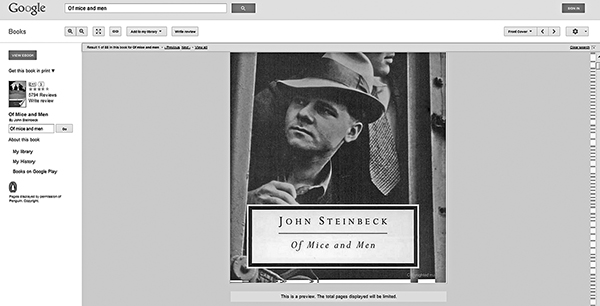

Preview access provides more of the text, allowing users to look at full pages within it, though still not at the whole text. In figure 8.3 one can see how the whole book is provided online, but certain pages are omitted. Google states just below the cover page that the amount of pages visible to readers will be limited.

In full view, all of the text is provided in open access to all readers. In its policy, Google states that “[its] partners decide how much of the book is browsable—anywhere from a few sample pages to the whole book. Some partners offer the entire book in a digital edition through Google eBooks, in which case you can purchase the book.”5

Figure 8.3

Preview view of Google Books, showing cover and basic metadata along with the note “This is a preview. The total pages displayed will be limited.”

Google appears to be attempting to provide accessibility to readers as well as marketability for authors within its system. As for authors or copyright owners who choose to provide the book openly, this follows much of the same rationale as platinum open access.

As stated earlier, there may be longer-term benefits for publishers and authors to provide titles in an open access environment. MDLs not only provide information in monograph form to users but also stimulate interest in a topic or publisher imprint. The focus of Google Books appears to be more on the general population, that is, as a digital public library on a mass scale. As a result, the publishers of trade and general interest publications involved with Google Books would likely benefit the most. Yet as we will see in the following sections, such considerations of audience are different since the intended users for other MDLs are of a more academic or cultural nature.

HathiTrust

The HathiTrust’s vision for its MDL has always been slightly different in scope and intent than the Google Books digitization project. While some may ascertain some questionable or at least profit-driven motives on the part of Google, the HathiTrust has taken great pains to avoid such legal entanglements. As a result of both its cautiousness relative to Google’s and its basic nonprofit educational philosophy, access to content in the HathiTrust MDL is more restricted. Instead of the four possible levels of access, there are only two: limited view and full view. Since the individual catalogs of each consortium partner and OCLC’s WorldCat already handle titles that are not digitized, the HathiTrust’s MDL is meant only to provide access to texts that have been digitized.

HathiTrust is a much more uniform, accountable, and streamlined system as a result. It is easy to surmise whether HathiTrust has a digital version of a book, which affects user trust.

The advantage of the HathiTrust is its metadata, based on the robust cataloging practices of its member libraries. For each of the records, regardless of snippet or full view, the following access points are provided:

• Main author

• Other authors

• Note

• Physical description

• Language(s)

• Published (year)

• Original format

• Original classification number

Additionally, the HathiTrust lists “Locate a Print Version” as part of its item description, and links out to OCLC’s WorldCat, which provides a list of the nearest libraries holding a physical copy of the work.

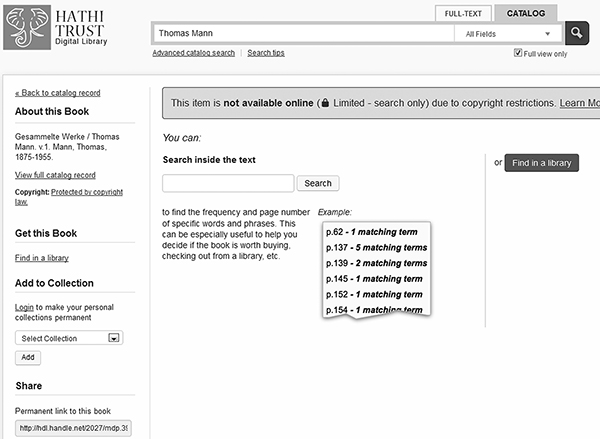

The limited view (see figure 8.4), similar to snippet view in Google Books, doesn’t allow nonmember users to see the text. The text itself, however, is searchable so that users might be able to infer whether the text had the types of information that they were looking for. The approach is a conservative one in several ways. It prevents outside users from “stealing” text. It protects copyright but also allows users to at least access some of the intellectual content of the source materials without shutting them out completely. Yet it is also a somewhat unsatisfying search experience for many users. It is questionable if matching queried keywords will provide the typical user with what he or she needs. It is also questionable whether such limitations also predetermine one’s fair use rights, much like digital rights management in music has been criticized, as one’s actions are curtailed even before one can try to use information. One is locked out before one can even try to apply the fair use doctrine to a text within the HathiTrust.

Figure 8.4

HathiTrust’s limited view and “search inside the text” function, for users to determine frequency of sought-after information.

The full view of the HathiTrust items allows users to access any part of the text. HathiTrust’s policy to bundle related files together like many institutional repositories is a significant improvement over the mishmash of records that Google Books provides users. This ability to provide access to multiple volumes through one access point improves findability.

The accessibility of these full texts is also limited, though. Only members of a partner institution can have access to downloadable PDF files. At-large users are restricted to browsing the texts on their online e-reader software. Sometimes this is sufficient. However, people who have a slow Internet connection or older computer, or who are missing the requisite software, will not be able to view the texts in a satisfactory manner. Furthermore, although controls exist to allow users to zoom or turn pages or refresh, text loading is time consuming and the user interface is awkward (see figure 8.5). To take full advantage of the texts, one must also have a large screen to be able to read the text.

Figure 8.5

HathiTrust’s full view, showing its online e-text reader in thumbnail page view and its user-interface controls.

Overall, the display allows users to get a sense of the text and to read not only the PDF original version but also, if one prefers, the OCR text only. Users can also search, view in full pages, zoom in and out, and rotate pages left or right.

Europeana

Europeana’s mission is to advocate for a stronger and more robust public domain. One of its strategies for strengthening the public domain is to work with Creative Commons licensing. This allows authors to predetermine copyrights so that end users and consumers can judge quickly and easily whether or not they can use a work for various purposes.

Although Google Books provides a partnership program for authors, it does not necessarily reflect a reliance on the Creative Commons movement. In many ways, as is often the case with Google, the project remains opaque, and it is unclear how many books are actually in the Google Books corpus. Europeana, however, appears willing to embrace international standards of cooperation such as the Creative Commons license.

Access to works licensed with Creative Commons is provided in ways similar to the HathiTrust, with some works available in limited view and others available in full text. A brief search for public domain works in the Europeana corpus yielded about two million results, a sizable collection of materials for users.

Open Library

The Open Library markets its service as “a record for every book.” As a result, its catalog contains millions of records for books in the same way that OCLC’s WorldCat does. However, it also allows users to access its digitized full-text works. As a result, accessibility is limited to two types: record only and full text. The record-only view provides basic metadata similar to Google Books. It is somewhat sparse with the presentation of the metadata. In the example shown in figure 8.6, the author is listed under the heading “people.” It also provides a blurb for describing the text and a table providing all of the available editions.

There are seventy-five editions of Goethe’s Egmont available. The table then provides a link to the various file formats, if available, and tells users how they can use the content: read, borrow, or buy.

The full-text view provides some interesting variations from other MDLs, however. First, the project provides a full-text option for any item that is in the public domain. Users can download or view in an online reader in various formats, including PDF HTML text markup, ePub, DjVu, MOBI and Kindle.

Figure 8.6

View of the Open Library record for Egmont, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

The hyperlinks often leave the Open Library domain to other MDLs, including the Internet Archive. Full access is also provided to disabled users via the Digital Accessible Information System (DAISY) format. The Americans with Disabilities Act often trumps concerns about copyright and allows users who are Open Library community members and who have registered DAISY accounts with accepted services such as the National Library Service (NLS) for the Blind and Physically Handicapped to access the texts. There are also open DAISY titles for anyone to use. Overall, the concern for people with disabilities to access texts is Open Library’s greatest strength.

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive lists as its policy uploading only those books that are in the public domain.6 As a result, there is only one level of accessibility in the system: full view. Searches for various texts that might yield records, snippets, or partial views in the other MDLs yield nothing in the Internet Archive. The collection is therefore 100 percent open access, but it is limited in the number of texts available. This limitation is also one of its strengths. When users find something in the Internet Archive, they can know with great certainty that it is available for download and immediate use.

Figure 8.7

Screenshot of the Internet Archive showing “The Harvard Classics eboxed set,” all fifty-one of the set’s digitized volumes in one record.

Users are able to acquire the content in the Internet Archive in a number of different ways. First, users can view the book online, and they can choose various file formats (e.g., PDFs, EPUBs, Kindle, Daisy, HTML OCR text, DjVU). All files are held on the server in one HTTPS index location as well. Metadata elements are provided for users, including author, subject, publisher, language, call numbers, digitization sponsors, and book contributors. Also included are technical metadata regarding the scanning equipment, policies, image parameters (e.g., PPI, OCR), and more. The robust metadata in the Internet Archive is far superior to that of Google Books and of the Open Library in terms of access points and rivals that of the HathiTrust. Even multiple files and volumes are occasionally bundled, as seen in the example in figure 8.7, although this is not applied uniformly to all titles in the Internet Archive as it is in the HathiTrust.

Conclusion

Access levels vary greatly with MDLs. On the one hand, open access in its varieties could easily be integrated into various MDLs, depending on their missions. Open access would surely raise the profile of many works that are currently locked or restricted by copyright. Platinum OA might be implemented by creating fee-supporting bodies out of current MDL consortia members. HathiTrust, with its implicit and explicit focus on academia, might be the best candidate for such a publishing endeavor. Gold OA could also be integrated with MDLs in much the same way, though it would be more successful with scaled article processing fees (APCs). Green OA would be possible to implement as well, but much longer embargo terms would have to be implemented to reflect the higher costs and longer periods of time needed to recoup publication expenses.

On the other hand, MDLs—as determined in the 2012 case Authors Guild v. HathiTrust—must respect the rights of the author of the source material.7 To do so, all MDLs have developed system features or overall content gathering policies that limit some visibility or acquisition of the text. Google Books is the least restrictive with its four levels of access; the more conservative HathiTrust provides two levels of access; Europeana provides open access to public domain works; Internet Archive provides one view only (full text of public domain materials); and the Open Library provides two levels as well. Open Library also allows community users to log in to access a limited amount of texts. At the same time it provides access to those with disabilities by offering both open and protected DAISY reader versions of texts.

Overall, access is being navigated by each of the MDLs in different ways. Although complete open access with MDLs will likely never happen, their philosophies generally overlap with the basic tenets of the OA movement. Perhaps if copyright laws loosen a bit with regard to digitized books, especially with orphan works, MDLs will be able to provide an even greater amount of open access.

References

Gardner, Rita. 2013. “Open Access and Learned Societies.” In Debating Open Access, ed. Nigel Vincent and Chris Wickham. London: British Academy. www.britac.ac.uk/openaccess/debatingopenaccess.cfm.

Grumpenberger, Christian, María-Antonia Ovalle-Perandones, and Juan Gorraiz. 2013. “On the Impact of Gold Open Access Journals.” Scientometrics 96, no. 1: 221–38.

Schruers, Matt. 2013. How Long Can Copyright Holders Wait to Sue? Disruptive Competition Project. www.project-disco.org/intellectual-property/100313-how-long-can-copyright-holders-wait-to-sue/.

Vincent, Nigel. 2013. “The Monograph Challenge.” In Debating Open Access, ed. Nigel Vincent and Chris Wickham. London: British Academy. www.britac.ac.uk/openaccess/debatingopenaccess.cfm.

Vincent, Nigel, and Chris Wickham. 2013. Introduction to Debating Open Access, ed. Nigel Vincent and Chris Wickham. London: British Academy. www.britac.ac.uk/openaccess/debatingopenaccess.cfm.

Notes

1. Ian Sample, “Harvard University Says It Can’t Afford Journal Publishers’ Prices,” Guardian, April 24, 2012, www.theguardian.com/science/2012/apr/24/harvard-university-journal-publishers-prices.

2. “Sticker Shock 2: Cost-Per-Use,” Cornell University, http://engineering.library.cornell.edu/about/stickershock_stats.

3. Eldred v. Ashcroft, 538 U.S. 916 (2003).

4. “Why Some Books Aren’t Available in Full-Text,” Google Books, https://support.google.com/books/answer/43729?topic=9259&hl=en.

5. Ibid.

6. Internet Archive Digital Library, https://archive.org/about/faqs.php.

7. Authors Guild v. HathiTrust, 902 F.Supp.2d 445, 104 U.S.P.Q.2d 1659, Copyr.L.Rep. ¶ 30327 (October 10, 2012).