8 Boletes

Boletes have a fleshy cap and central stalk like most gilled mushrooms, but the gills are replaced by a sponge layer. The surface of the sponge is composed of hundreds of pores, but may appear smooth when very young. The pores are the mouths of closely packed spore-bearing tubes (see photo on this page) that constitute the sponge layer. A veil is absent in most boletes; when present it covers the sponge surface in young specimens. Most boletes grow on the ground. Polypores also have a sponge layer but are tougher and usually grow on wood (but see the blue-capped polypore, this page).

The king bolete and its relatives are among the most renowned of all mushrooms. A few boletes are poisonous, notably those with reddish pores. If your bolete is not among those depicted here, see MD 488–545.

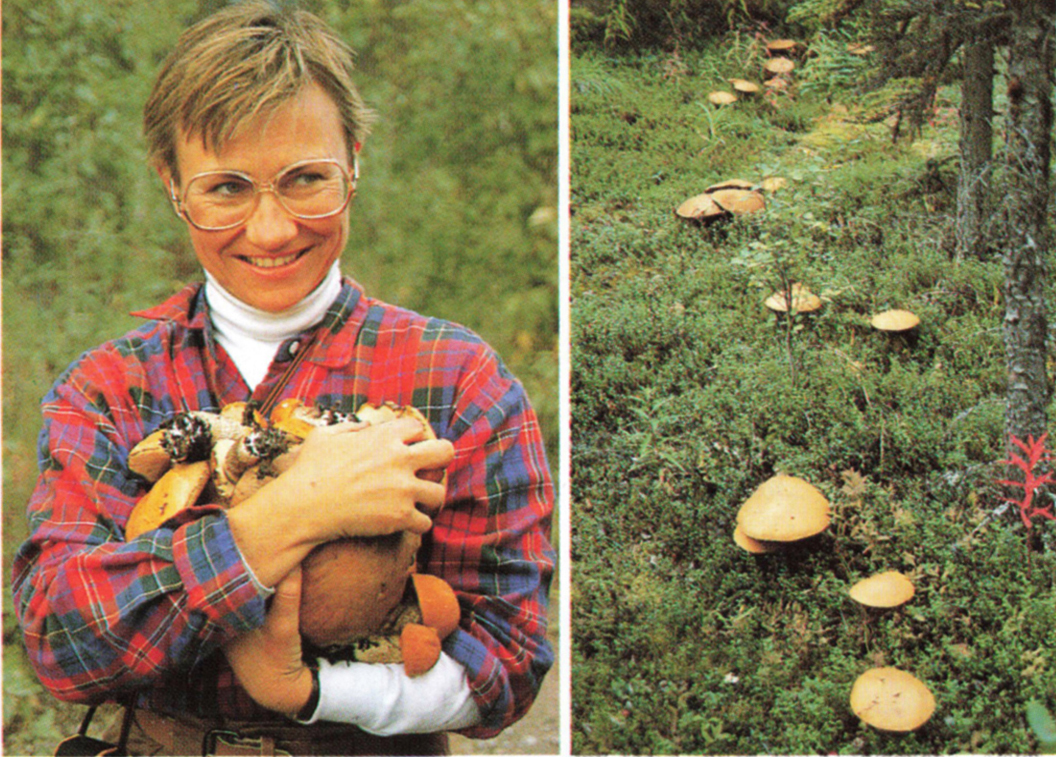

A perfectly matched pair of orange birch boletes (this page).

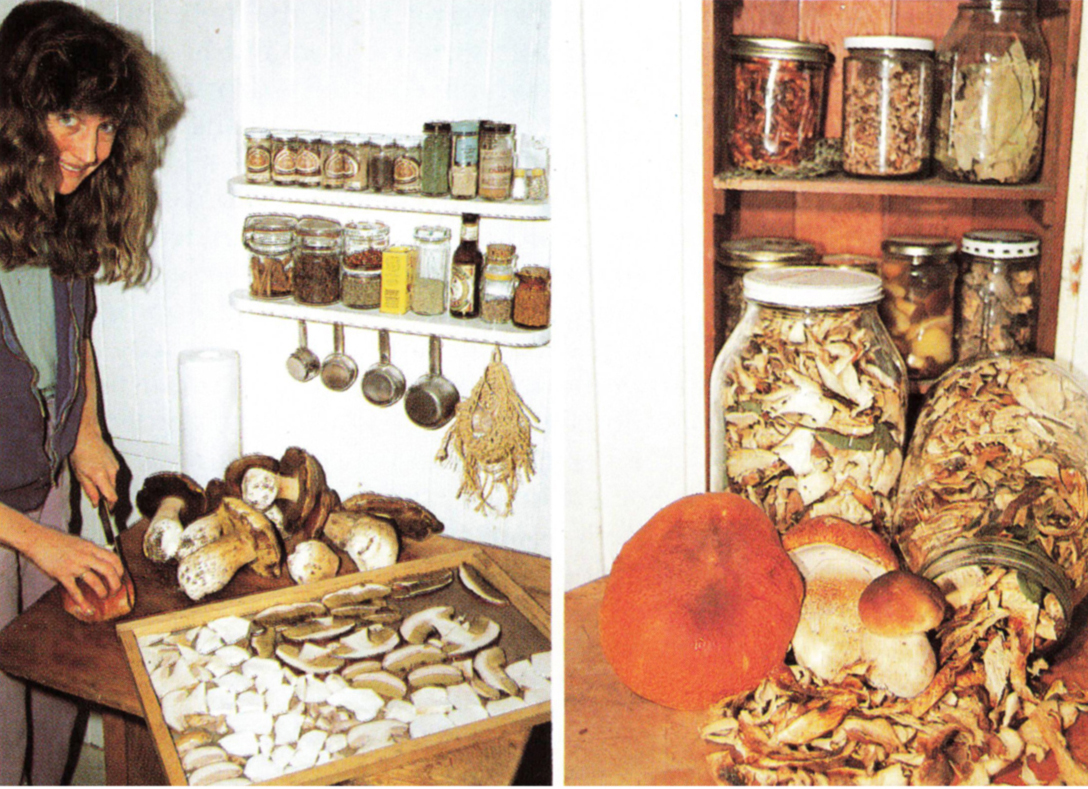

Another matching pair: mother and daughter with Boletus edulis.

King boletes sliced to show the tubes.

Roasted leccinums.

Ahmed Soumitte and Boletus edulis

On Cooking Boletes

All boletes have a high water content which can cause them to cook up watery or slimy. Dry-sauteeing them (see this page) will drive off the excess moisture while concentrating their flavor. Removing the tubes (sponge layer) before cooking will also help, as they are even more watery than the cap and stalk. The tubes are full of flavor, however, and can be dried separately for use in gravies and soups (see “Essence of Edulis,” this page). Bolete caps are also delicious basted with a little olive oil, and grilled on an open fire (see this page).

King Bolete (Boletus edulis)

Other Names: Cep, Porcini, Steinpilz, etc.

Key Features:

1. Cap brown to yellow-brown, red-brown, or dark red (but often whitish when still covered by humus), bald.

2. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface white when young, then yellowish, brown, or olive in age, not staining blue or brown when bruised.

3. Stalk thick (at least 1″), white to brown (never yellow).

4. Stalk surface finely netted, at least at top.

5. Flesh white, not staining blue or brown when cut.

6. Taste mild or nutty, not bitter.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large; cap sticky or dry; individual pores barely visible when white; stalk often with a bulb when young, often straighter in age; veil absent; spores dark olive-brown.

Where: On ground in woods and at their edges, often in groups; widespread and common. It favors conifers (especially pine, fir, spruce) but also occurs with oak and birch. In high mountains, the major crop is in the summer; at lower elevations, about three weeks after the first fall rains. A flush may also appear in the spring during morel season.

Edibility: One of the most sought after of all mushrooms, delectable fresh or dried.

Note: This magnificent mushroom has several forms that may be distinct species. The thick white flesh does not stain blue as in many boletes, or will at the very most blue slightly where the flesh meets the tubes. Plump as a “little pig” (porcini), no mushroom is more substantial or satisfying to find! See this page and below for more photos; also see MD 530–531 and plate 144.

This reddish-capped form of the king bolete is common in New Mexico.

Bolete Your Heart Out

It was August before I realized there was only a quart of dried boletus left on my shelf. To say panic ensued is an understatement. I was desperate. Distraught.

So I did what any desperate, distraught bolete eater would do, I went to the library and consulted the following: One Hundred Steps to the World’s Ceps; Almanac to Boletus Blooms, 1938; Hideaway Boletus Spots for the Discriminating Collector; and September First Is Too Late: A Guide to Boletus Bounties in the American Southwest. Of course there were some disagreements (and more than a little vagueness) about the exact locations of the tastiest ceps, the most underexploited blooms, the collecting regions with the best wine and hare, but there was a general consensus that a person in my predicament should be in New Mexico in the middle of August.

A few days later I found myself in the high mountains of New Mexico, walking along the edge of a spruce forest. Aside from the fact that I was dizzy and couldn’t bound around in my usual way, there was absolutely no challenge to it. My boletus stick was useless because the boletes didn’t hide under the duff like they do in California. Instead they stood straight up, like statues. In an hour and a half I had filled up three containers.

My plan was to dry them all out in the morning sun. But later, alone, inching through the maggot removal and chop-ping-cleaning process, I confess that a new dimension of the expression “his eyes are bigger than his stomach” was revealed. As several pounds of boletes melted into oblivion I came to the realization that if I don’t temper my greed, upon my death I will find myself in that portion of hell reserved for boletivores who, in punishment for their intemperance, are condemned to a limitless future cleaning an endless quantity of squirming, maggoty mushroom entrails.

Nevertheless, next August will find me in New Mexico. I’ll leave the boletus stick and bring the binoculars.

—William Rubel

Italian-American Boletivores

Not very long ago, most of the bolete eaters in North America were immigrants from mushroom-loving countries. In California, Italian-Americans like John Feci (above right) and Enrico Re (above left) were especially prominent in the woods. Feci reminisces:

When I was ten or twelve, I used to hunt with the older guys. They were vegetable farmers, in their forties and fifties. They couldn’t speak English, but they had class. They weren’t in a hurry. They did a lot of things by hand like make their own wine and cheese and salami and mondiola, which we’d have for lunch while they told stories of the olden days.

We’d get up early and pile into the car like Al Capone and his gang: six guys in a Buick wearing fedoras — we didn’t have the visor caps with the advertisements like they have now. The first time I went we had an automobile called a Chandler, and we couldn’t make it up the hill, even in low gear. So we stopped and found a pile of boletes and coccora right there, but a lady caught us and made us give them all to her. We never found any hidden loot or bodies, but it got pretty intense. We’d see who could find the most. When we found some cupetta we wouldn’t say “hey, come over here,” like you do in a mushroom class. Instead we’d keep real quiet and try to get as many as possible before the others found out.

Outsiders called us “the Italian community,” but we were more like little tribes. We didn’t fraternize. We’d see a lot of Italians hunting in the woods, but they didn’t speak our dialect and we’d steer clear of them. The older guys all came from the same place, Campi, and they always made a big distinction between the people from Campi and the people from Pieve di Campi. Years later when I went to Italy I discovered that Campi was on a hill and Pieve di Campi was at the bottom, a couple miles away.

Enrico (“Rico”) Re has hunted mushrooms for more than sixty years, since his childhood in Italy and Switzerland. Each fall he begins looking for boletes two weeks after the first inch of rain (“a half inch is no good”); he says hunting is best between the full moon and new moon. Rico likes to go “slow, slow”; he doesn’t hunt to be social. He always goes alone, arriving at his favorite spot before dawn, where he waits until the sun comes up. Why does he go so early and so often? “It’s what I do. When it starts raining, that’s my job. When I find a big mushroom, I feel rich. I’m a king.”

While more and more North Americans are discovering wild mushrooms, those who come from a long foraging tradition like John and Rico are a vanishing breed. Their children are not carrying on the tradition, perhaps because they perceive mushroom hunting as un-American. The principal measure of their success is having money, not time or knowledge. Rico’s daughter won’t eat the boletes he gathers, even though she knows they’re delicious. “Why should I?,” she asks, “when I can buy mushrooms at the store?”

Essence of Edulis

Sliced and dried king boletes are fantastically flavorful. Just soak them in water for about 20 minutes and then saute them for use in any dish. The tubes, however, are slimy when reconstituted, so it is better to dry them separately, soak them overnight, and use the liquid. Give the soaked tubes a good wringing before throwing them out (they will have lost nearly all of their flavor), then thicken the liquid with a roux (flour and butter) and season with a little salt. You now have essence of edulis, which you can dilute to your liking. It makes an exceptional vegetarian gravy for potatoes or rice, or can be used as a soup stock.

Slicing and drying king boletes concentrates their superb flavor.

A basket of king boletes (this page).

In a forest feckless fungophile Fred

Had a thief point a gun at his head

“Keep your jewels and gold!”

Said the highwayman bold,

“I’ll take your basket of boletes instead!”

—Charles Sutton

The Russian Sport of hodit’ po gribi

[In rainy weather, the park’s] shady recesses would harbor that special boletic reek which makes a Russian’s nostrils dilate…. All alone in the drizzle, my mother, carrying a basket, would set out on a long collecting tour. Toward dinnertime, she could be seen emerging from the nebulous depths of a park alley, her small figure cloaked and hooded in greenish-brown wool, on which countless droplets of moisture made a kind of mist all around her. As she came nearer from under the dripping trees and caught sight of me, her face would show an odd, cheerless expression, which might have spelled poor luck, but which I knew was the tense, jealously contained beatitude of the successful hunter. Just before reaching me, with an abrupt, drooping movement of the arm and shoulder and a “Pouf!” of magnified exhaustion, she would let her basket sag, in order to stress its weight, its fabulous fullness…On a round garden table she would lay out her boletes in concentric circles to count and sort them. For a moment, before they were bundled away by a servant to a doom that did not interest her, she would stand admiring them, in a glow of quiet contentment.

—from Speak, Memory by Vladimir Nabokov

Queen Bolete (Boletus aereus)

Other Names: Moretti.

Key Features:

1. Cap dark brown when young.

2. Surface of cap with a fine whitish bloom when very young, otherwise bald.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface white when young, becoming yellowish and finally greenish as it matures, not staining blue or brown when bruised.

4. Stalk at least 1” thick at top, white to brown (not yellow).

5. Stalk surface finely netted, at least at top.

6. Flesh white, not staining blue or brown when cut.

7. Taste mild or nutty, not bitter.

8. Associated mainly with hardwoods.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large; cap often reddish-brown and/or with pale areas when mature, sticky or dry; individual pores barely visible when white; stalk often with a bulb when young, but straighter in age; veil absent; spores dark olive-brown.

Where: On ground under hardwoods (tanoak, madrone, chinquapin, manzanita, oak) or sometimes conifers. Common in California and Oregon; northern limit uncertain.

Edibility: Excellent. Some prefer it to the king bolete; others say it is bland unless dried.

Note: This species differs from the king bolete mainly in the cap color of young individuals. When older the two can be similar, although the pore surface is usually greenish in the queen bolete rather than brown as in the king. See MD 531 and plate 140.

White King Bolete (Boletus barrowsii)

Key Features:

1. Cap white to pale gray or buff, bald, not sticky or slimy.

2. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface white when young, then yellowish and finally olive or brownish, not staining blue or brown when bruised.

3. Stalk thick (at least 1”), whitish (never yellow).

4. Stalk surface finely netted, at least at top.

5. Flesh white, not staining blue or brown when bruised or cut.

6. Taste mild or nutty, not bitter.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large; individual pores barely visible when white; stalk with or without a bulb at base; veil absent; spores dark olive-brown.

Where: On ground in forests and at their edges, often in groups; restricted to drier regions (Great Basin, Southwest, California). In the Southwest it is often abundant under ponderosa pine; in coastal California it favors oak.

Edibility: Excellent — as good as the king bolete.

Note: For many years this handsome mushroom passed as a white form of the king bolete. It was finally recognized as a distinct species and named after Chuck Barrows (this page), who pioneered the study of mushrooms in New Mexico and the Southwest. See MD 529 for more information.

This mature, handsome white king bolete weighed almost 3 lbs. It was found under an oak in coastal California.

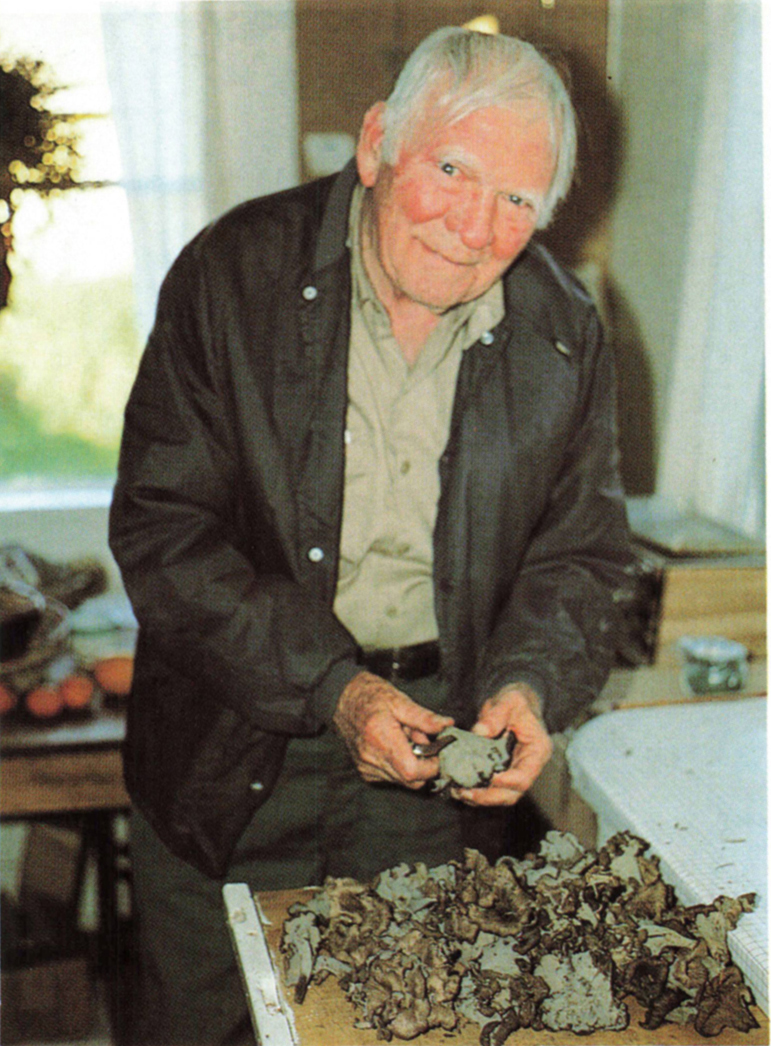

Chuck Barrows with Craterellus cornucopioides (this page).

My Most Memorable Mushroom Hunt

It was right after Paracutin erupted. There was still ash in the air, and on the blackened hillsides was a ghost forest of charred stumps completely covered with masses of sulfur shelves. It was incredibly eerie, like Halloween, as if the stumps themselves had erupted.

Another time in Mexico I found some blue-staining mushrooms in a pasture. I knew they weren’t deadly poisonous, so I put them in an omelet and spent the next few hours under a blanket in the back seat of the car, laughing hysterically. My friends didn’t understand. Neither did I except that I knew I was having one helluva time. They must have been psilocybes, but this was long before hallucinogenic mushrooms were known to science or hippies.

My most memorable recent hunt was in California. I’d wanted to taste Craterellus all my life, but they don’t grow in New Mexico. So when I finally found some in California, at age eighty, I danced with delight. It was the last mushroom I ate for the first time, and well worth the wait — almost as good as Boletus barrowsii, which is the best mushroom in the world.

—Chuck Barrows

Bitter Bolete (Boletus rubripes)

Other Names: Red-stemmed Bitter Bolete.

Key Features:

1. Cap tan, buff, or olive-buff, not sticky or slimy.

2. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface yellow, but quickly staining blue when bruised.

3. Stalk partly or entirely red or rhubarb-colored, the upper part not finely netted.

4. Flesh pale yellow to whitish, staining blue when cut or bruised.

5. Taste bitter (chew on a small piece of cap, then spit it out).

Other Features: Medium-sized to fairly large; cap surface smooth or with cracks; stalk at least 1” thick, sometimes with a bulb when young, but usually straighter in age; veil absent; spores olive-brown.

Where: On ground under conifers; fairly common from the Pacific Northwest to northern California, and in the mountains to the Southwest.

Edibility: Tempting, but bitter. Cooking it doesn’t help.

Note: There are several hefty, blue-staining, bitter boletes in the West, including: B. coniferarum of the Pacific Northwest, with a yellow to olive (not red) stalk that is finely netted at the top; B. calopus, found under mountain conifers, with at least some red or pink on its netted stalk; and B. albidus, with a pale cap and yellowish stalk, found under oak in California. See MD 523-525 and plate 130.

Butter Bolete (Boletus appendiculatus)

Key Features:

1. Cap yellow-brown, brown, or rusty-brown.

2. Surface of cap bald, not sticky or slimy.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface yellow, but blueing when bruised.

4. Stalk thick (>1″), yellow, at least the upper part finely netted.

5. Taste mild (not bitter).

6. Flesh thick and dense, pale yellow except in base of stalk, blueing erratically, if at all, when cut.

7. Flesh in base of stalk pinkish, tan, or burgundy.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large; base of stalk often (but not always) thickened or with a bulb; veil absent; spores dark olive-brown.

Where: Common on ground under hardwoods (oak, tanoak, madrone) in California; also reported from conifer forests in Oregon and Idaho.

Edibility: Edible; not nearly as sweet as the king bolete, but with wonderfully dense flesh.

Note: The large size and meaty flesh make this bolete popular with California collectors. The red-capped butter bolete, B. regius, is very similar but for its rose-colored cap (see MD plate 133); it occurs in California and the Pacific Northwest under both hardwoods and conifers. See MD 525-526 and plate 134.

Admirable Bolete (Boletus mirabilis)

Key Features:

1. Cap dark brown to maroon-brown or red-brown.

2. Surface of cap roughened by many small scales or plushlike hairs, not sticky or slimy.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface yellow to greenish-yellow, not blueing when bruised.

4. Stalk colored more or less like cap, often long (>4″).

5. Base of stalk usually thicker than top.

6. Veil absent.

Other Features: Medium-sized; cap domed when young, flatter in age; flesh not blueing; pore surface often staining dark yellow when bruised; stalk usually netted, pitted, ridged, or streaked; spores dark olive-brown.

Where: Solitary or in small groups on or near rotting conifers, especially hemlock; common in northern California and the Pacific Northwest.

Edibility: Edible; it has a lemony flavor.

Note: This beautiful mushroom is easy to recognize. Its fondness for rotten wood is unusual for a bolete. See MD 521–522 and plates 127, 129.

I forgot falling off the horse

With the happiness

Of finding mushrooms.

—Ukei

Zeller’s Bolete (Boletus zelleri)

Key Features:

1. Cap black to dark gray, sometimes with a reddish tinge (i.e., reddish-black).

2. Surface of cap not sticky or slimy, often wrinkled or uneven but not extensively cracked or fissured.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface yellow to olive-yellow.

4. Stalk partly or entirely red or rhubarb-colored (usually red and yellow when young and entirely red in age except for base).

5. Taste mild, not bitter.

Other Features: Medium-sized; flesh whitish to yellow, blueing slightly or not at all when cut and rubbed; pore surface often but not always blueing when bruised; stalk without a bulb, the surface not netted; veil absent; spores olive-brown.

Where: On ground or rotten wood in forests and at their edges; Pacific Northwest and California. It is common under both hardwoods and conifers.

Edibility: Edible.

Note: The colorful combination of dark cap, yellow pores that sometimes stain blue, and red stalk is very striking. Similar species, such as B. chrysenteron and B. truncatus, show extensive cracks or fissures on the cap at maturity, and are usually paler. See MD 518–520 and plate 128.

Slender Red-pored Bolete (Boletus erythropus)

Key Features:

1. Medium-sized: cap 2–6″ broad, top of stalk ½-1½″ thick.

2. Cap brown to dark brown, sometimes shaded with red.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface red when fresh, staining blue or blue-black when bruised.

4. Stalk without a bulb at base.

5. Stalk yellowish, but the yellow often masked by tiny reddish dots or flakes; upper part not netted.

6. Flesh quickly staining blue when cut or bruised.

7. Associated with conifers.

Other Features: Cap bald or velvety, not sticky or slimy; pore surface sometimes orangish in old age; sponge layer yellow (except for red surface); stalk often rather long, the base sometimes with tiny velvety hairs; veil absent; spores brown to olive-brown.

Where: On ground near or under northern conifers (spruce, hemlock, fir); fairly common from Alaska to northern California, also reported from the Rocky Mountains.

Edibility: Poisonous, causing gastrointestinal distress.

Note: This beautiful mushroom is not as bulky as the other red-pored boletes, and the surface of the upper stalk is not netted. Similar species include B. subvelutipes of the Southwest, with a blond to yellow-brown cap and reddish to orange pore surface (see MD plates 135-136); and B. amygdalinus, common under oak and madrone in California, with an orange to brick-red pore surface. See MD 526-527 for more information.

Red-pored Bolete (Boletus pulcherrimus)

Key Features:

1. Cap brown to reddish, often with dark fibers or small scales.

2. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface deep red to red when fresh, staining blue or blue-black when bruised.

3. Stalk partly or completely reddish to reddish-brown.

4. Stalk surface finely netted, at least at top.

5. Stalk without a blatant bulb at base (but base often thicker than top).

6. Flesh quickly staining blue when bruised or cut.

7. Associated with conifers.

Other Features: Medium-sized to fairly large; cap not sticky or slimy; pore surface often orange or even yellowish in old age as the yellow color of the tubes (sponge layer) shows through; netting on stalk usually red or red-brown; veil absent; spores dark olive-brown.

Where: On ground near or under conifers from British Columbia to northern California, and in the Rocky Mountains and Southwest; common some years.

Edibility: Poisonous; causes severe gastrointestinal distress.

Note: The beautiful red pore surface and fine red netting on the stalk make this a memorable find. It is sometimes confused with B. haematinus (MD plate 138), a similar red-pored alpine species with a yellower netted stalk and brown to yellow-brown or olive-brown cap. Neither of these is as obese as satan’s bolete. See MD 528 for more information.

Satan’s Bolete (Boletus satanas)

Key Features:

1. Cap whitish, grayish, or olive-gray, sometimes with a rosy blush in old age.

2. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface red when young and fresh, staining blue when bruised.

3. Stalk with a large bulb at base.

4. Surface of upper stalk finely netted.

5. Flesh quickly staining blue when bruised or cut.

6. Associated with oak.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large; cap bald, not sticky or slimy; pore surface often orange or even yellowish in old age as the yellow color of the tubes (sponge layer) shows through; bulb on stalk usually pink or rosy when young, often paler in age; netting on upper stalk usually reddish; veil absent; spores brown or olive-brown.

Where: On ground near or under oak; California and Oregon. It is sometimes abundant after the very first fall rains, a week or more before the king bolete.

Edibility: Poisonous; causes severe gastrointestinal distress.

Note: Even when the beautiful red color of the pore surface has faded, this bolete can be recognized by its briskly blueing flesh and blatantly bulbous stalk. Specimens weighing several pounds are not unusual. See MD 527-528 for more information.

Birch Bolete (Leccinum scabrum)

Other Names: Rough-stemmed Bolete, Brown Birch Bolete.

Key Features:

1. Cap tan, brown, or gray (in age sometimes with an olive tinge), not orange or reddish.

2. Edge of cap not rimmed with flaps of tissue.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface whitish when young, grayish to dingy brown in age, not blueing when bruised.

4. Stalk with numerous small projecting scales, the scales brown to black (at least at maturity).

5. Flesh white, discoloring only slightly if at all when cut and rubbed.

6. Associated with birch.

Other Features: Medium-sized; cap not slimy; stalk without a bulb, the lower part sometimes with blue or blue-green stains; veil absent; spores brown.

Where: On ground in woods or bogs near or under birch; widespread in lawns or parks where birches have been planted, and common in the wild from Washington and Montana northward.

Edibility: Edible.

Note: There are several similar edible species associated with birch. One, L. holopus, has a whitish cap. In another, L. alaskanum, the cap is mottled with dark and light areas. Still another, L. rotundifoliae, grows in tundra with dwarf birch. See MD 541-542 for more information.

Aspen Bolete (Leccinum insigne)

Other Names: Aspen Scaber Stalk.

Key Features:

1. Cap orange to orange-brown or red-brown when fresh (but often paler or duller when older).

2. Surface of cap dry or very slightly tacky to the touch, not sticky or slimy.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface whitish to grayish to dingy yellow-brown, not blueing when bruised.

4. Stalk whitish with numerous small projecting scales, the scales brown to black (at least at maturity).

5. Flesh white, but staining purple-gray to black when cut and rubbed repeatedly (especially at juncture of cap and stalk).

6. Associated with aspen.

Other Features: Medium-sized to fairly large; cap bald, the edge rimmed with thin flaps of tissue, at least when young; stalk without a bulb, the lower part often with blue or blue-green stains; veil absent; spores brown.

Where: On ground near aspen, often in groups or troops; abundant in northern latitudes and southward in mountains (Sierra Nevada, Rockies, etc.) wherever aspen occurs. It often fruits in June or July, before most mushrooms appear.

Edibility: Excellent; it darkens when cooked.

Note: Leccinum contains many edible species that closely resemble this one. In some, such as L. aurantiacum (found with conifers as well as aspen), the cut flesh stains reddish or burgundy before slowly darkening. See MD 540-541 and plate 147.

Panhandled Boletes

(a satyrical account)

We were driving through the Alaskan wilderness: nothing but aspen, birch, and spruce, the horizon crowned by two snowy volcanoes. There were so many mushrooms that we just had to stop. You should have heard us shrieking — we bolted out of the van like kids out of a classroom, not even bothering to grab our baskets and knives. I must have been seized by a razh — one of those mushroom passions the Russians rhapsodize about — because as I lunged from one mushroom to another, snatching them up with pagan fervor, I wasn’t thinking about where I was going. I wasn’t thinking at all.

When I finally recovered my senses, my arms were loaded with leccinums and there was an absolute quality to my surroundings that I hadn’t noticed before. Absolute as in absolute silence. Absolute as in absolutely no roads for hundreds of miles except for the thin, winding gravel track we’d come in on. Absolute as in abslutely no idea where I was or how to find that tenuous connecting thread to civilization. Absolute as in absolutely alone with absolutely nothing to eat, not even a cheese sandwich. Wherever it was, the cramped van suddenly seemed almost comfortable, safe, and infinitely preferable to the prospect of hiding out from grizzlies and gnawing on raw leccinums for the rest of my life. Then my ears perked up. Was it my imagination, or were those the faint, ethereal notes of a flute drifting toward me through the aspen leaves? I couldn’t believe it. I sprinted off to find the source, still tightly clutching my bolete bounty despite the thickets of leccinums looming up in my path…

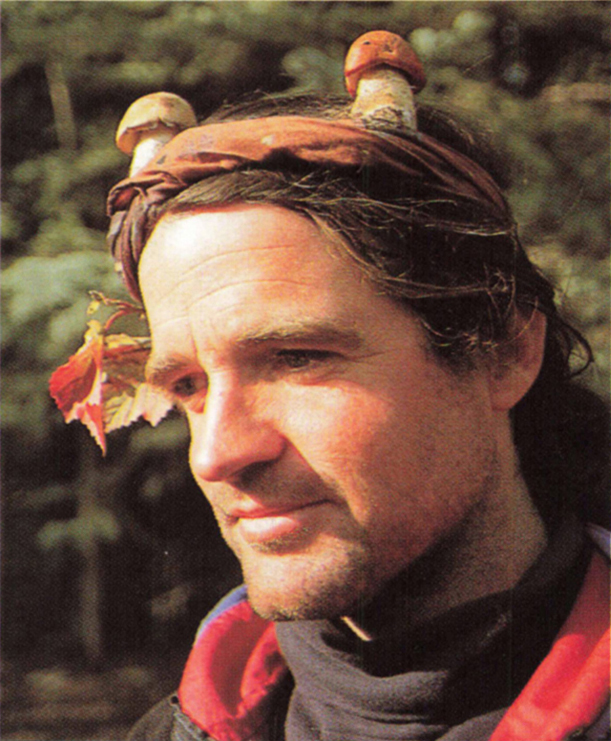

After a frantic few minutes, I came to the edge of a glade and there, perched on a large lichened rock, was a horned, barefoot Panlike figure, nimbly playing a flute. The others stood there spellbound; like me they were laden with leccinums and had been hopelessly lost.

Then the horned figure led us, like the Pied Piper, on a merry, meandering march through that glistening, mossy, mushroom-lush wonderland. It was unbelievable — herds of hawk wings, throngs of lofty leccinums, giant fairy rings of elegant amanitas, and logs so thick with clustered caps their bark couldn’t be seen. We must have looked like wood nymphs as we danced along together, completely caught up in the abundance and exuberance of the moment.

Finally he delivered us to the gravel road, where our abandoned van stood like an empty, ominous shell from some remote and irrelevant war. We offered our savior the mushrooms, which he, having a forest full of them, declined. He did allow himself to be photographed, however. Then, with an impish wink, he vanished into the forest as mysteriously as he had appeared. For a long time we stood there, straining to hear his flute, but there was nothing but the rustle of leaves in the breeze.

—Sue Willis

Orange Birch Bolete (Leccinum testaceoscabrum)

Other Names: Leccinum versipelle.

Key Features:

1. Cap orange when fresh (but often fading to tan with age), not slimy.

2. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface dark gray or olive-gray when young, paler in age.

3. Stalk covered with a dense layer of small projecting scales that are coal-black even when very young.

4. Associated with birch.

Other Features: Medium-sized to fairly large; edge of cap rimmed with thin flaps of tissue, at least when young; flesh darkening when cut (it may or may not stain reddish before darkening); lower stalk often with blue or blue-green stains; veil absent; spores brown.

Where: On ground near or under birch, often in large numbers; common in Alaska, south to the Rocky Mountains.

Edibility: Excellent dried or fresh, although it darkens when cooked. As with most edible mushrooms, a few people are adversely affected by it.

Note: Every summer the birch forests of Alaska and Canada swarm with these handsome boletes. In most leccinums the scabers darken gradually with age, but in this one they are black even when young, as if the stalk were dusted with coal. L. atrostipitatum is a very similar birch-loving bolete with a slightly duller (browner) cap. See photo on this page and MD 541 for more information.

Manzanita Bolete (Leccinum manzanitae)

Other Names: Madrone Bolete.

Key Features:

1. Cap dark red to red-brown when fresh.

2. Surface of cap sticky or slimy when moist.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface whitish to grayish to dingy olive, not blueing when bruised.

4. Stalk whitish with numerous small projecting scales, the scales brown to black (at least at maturity).

5. Flesh white, darkening erratically (often slowly or only in some areas) to purple-gray or black when cut and rubbed repeatedly.

6. Associated with madrone or manzanita.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large; edge of cap rimmed with thin flaps of tissue, at least when young; stalk with or without a bulb, the lower part often with bright blue or blue-green stains; veil absent; spores brown.

Where: On ground in madrone woodlands and manzanita thickets; common from central California to southern Oregon, less frequent northward.

Edibility: Bland; not nearly as good as the aspen and birch boletes. Drying improves the flavor somewhat.

Note: In many regions where aspen and birch do not occur, this is the dominant leccinum. It is often gathered by Italian-Americans along with the king and queen boletes. Several closely related edible species also occur with madrone and manzanita, including L. armeniacum, which has an oranger cap. See MD 539-540 and plate 145.

Short-stemmed Slippery Jack (Suillus brevipes)

Key Features:

1. Cap dark brown to reddish-brown when fresh (but sometimes fading to tan or even yellowish with age).

2. Surface of cap sticky or slimy when moist, bald, the edge without white veil tissue.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface white when young, pale to dull yellow in age, not blueing when bruised.

4. Pores not arranged in radiating rows.

5. Stalk usually <1″ thick, of more or less equal diameter throughout, white to pale yellow.

6. Stalk surface without brown spots, not netted.

7. Veil absent in all stages.

8. Associated with pine.

Other Features: Medium-sized; flesh white to pale yellow, not blueing; stalk solid, often but not always short; spores olive-brown to dull cinnamon.

Where: On ground near or under pines in forests and plantations, along highways and in yards, often in masses or troops; widespread and common — perhaps the most abundant slippery jack in western North America.

Edibility: Fairly good; remove the slimy skin before cooking.

Note: The absence of a veil and lack of brown spots on the stalk distinguish this slippery jack from most of its slimy brethren. See MD 501-502 for more information.

Granulated Slippery Jack (Suillus granulatus)

Other Names: Dotted-stalked Slippery Jack.

Key Features:

1. Mature cap brown to cinnamon (often paler when young).

2. Surface of cap sticky or slimy when moist, bald, the edge without white veil tissue.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface white when young, yellowish in age, not blueing when bruised.

4. Pores not arranged in radiating rows.

5. Stalk surface with prominent resinous brown or red-brown spots (at least when mature), not netted.

6. Veil absent in all stages.

7. Associated with pine.

Other Features: Medium-sized; flesh white when young, pale yellow in age, not blueing; pore surface of young, moist specimens often beaded with milky droplets; stalk white at first, yellowish at top in age, of more or less equal width throughout; spores olive-brown to cinnamon-brown.

Where: Often abundant on ground with pines; widespread, but replaced in some regions by other slippery jacks.

Edibility: Some people are fond of it; remove the slimy skin before cooking.

Note: This widespread slippery jack has many edible look-alikes. One of these, S. albidipes, shows cottony white tissue on the edge of the young cap. In another, S. punctatipes, the pores are arranged in more or less radiating rows. Two other species are shown below. See MD 502-503 for more information.

The pungent slippery jack (S. pungens) of California is chameleonlike: when very young the cap is white but soon becomes grayish and then olive-gray; then as it matures it turns yellow, orange, cinnamon, or brown, or is frequently mottled with all or some of these colors. It is abundant every year under Monterey pine and other coastal pines.

Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, and Slime

Slippery jacks are so abundant that one is always looking for ways to use them. Even with their skins removed they cook up slimy. Some people get rid of the sliminess by drying and powdering them, then adding the powder to soups and gravies. Another approach is to take advantage of their inherent wetness by substituting them for escargot, as follows:

Simmer 12 small, wet slippery jack caps (preferably collected just after a rain) for 3-4 hours in a pot of water laced with finely diced carrots, shallots, salt, and a bouquet of parsley, sage, and rosemary. Take 12 clean, empty snail shells and stuff each one with a dollop of garlic butter and a boiled slippery jack. Place in a casserole dish with a little water and butter, and a sprinkling of fresh bread crumbs. Warm in the oven and serve.

The Kaibab slippery jack (S. kaibabensis) resembles S. granulatus but has a yellower cap; it grows in the Southwest under ponderosa pine.

Poor Man’s Slippery Jack (Suillus tomentosus)

Other Names: Blue-staining Slippery Jack, Woolly-capped Suillus.

Key Features:

1. Cap with gray, brown, or reddish hairs, fibers, or small scales on a yellowish to orangish background; hairs scattered to dense depending on age and weather.

2. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface brown at first, yellowish in age (not white).

3. Pores not arranged in radiating rows.

4. Flesh and pore surface blueing when bruised or cut (sometimes slowly or only slightly).

5. Stalk yellowish to dull orange with darker spots or smears.

6. Veil absent in all stages.

Other Features: Medium-sized; cap sticky in wet weather unless covered with fibers; stalk not netted, the spots brown in age, resinous; spores olive-brown to dull cinnamon.

Where: On ground near or under conifers (mainly 2-needle pines); widespread and often abundant in most mountain ranges, and in coastal forests north of San Francisco.

Edibility: Insipid. In a group noted for its blandness, it ranks near the bottom. According to one collector, however, it smells and tastes like Tootsie Rolls when dried.

Note: This is our only common blue-staining slippery jack without a veil. Another “poor man’s slippery jack,” S. fuscotomentosus, has oranger pores when young and does not stain blue. See MD 504-505 and plates 119-120.

Slim Jack (Suillus umbonatus)

Other Names: Umbonate Slippery Jack.

Key Features:

1. Cap rather small (1-3″), yellowish to tan, often with an olive tinge when old.

2. Surface of cap sticky or slimy when moist, bald.

3. Underside of cap with a yellowish to olive-yellow sponge (pore) layer.

4. Individual pores large (at least 1 mm in diameter), arranged more or less in radiating rows.

5. Stalk slender (<½″ thick throughout).

6. Sticky or slimy veil present, at first covering pore surface, then usually forming a gelatinous ring on stalk.

7. Associated with pine.

Other Features: Cap often with an umbo (a low central knob); stalk solid, with obscure resinous spots that become more evident with age; no part of mushroom blueing when bruised; spores olive-brown to dull cinnamon.

Where: On ground near 2-needle pines, often abundant; southeastern Alaska to California and Colorado.

Edibility: Insipid and slimy.

Note: There are several slippery jacks (Suillus species) with a ring on the stalk; this one is the smallest. Others include S. subolivaceus (the slippery jill — see MD plate 121) and S. sibiricus (the Siberian slippery jack, which only sometimes has a ring — see MD plate 116), both common with 5-needle pines; and S. luteus (MD plate 118), usually with planted pines. See MD 498-500 for more information.

Fat Jack (Suillus caerulescens & S. ponderosus)

Other Names: Douglas-fir Suillus.

Key Features:

1. Cap orangish to yellowish, yellow-brown, or tan (or sometimes stained dark green).

2. Surface of cap sticky when moist, bald or with a few scattered fibers.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface yellowish when fresh, not blueing when bruised.

4. Stalk solid within, at least the lower part blueing when cut and rubbed (sometimes slowly or weakly).

5. Stalk surface without resinous spots.

6. Veil present, at first covering the pore surface, then disappearing or forming a slight ring on stalk.

7. Associated with Douglas-fir.

Other Features: Medium-sized to large; pores sometimes arranged in radiating rows, staining reddish or brown where bruised, attached to stalk or running down it; veil sticky or dry, white to yellow-orange; spores brown to cinnamon.

Where: On ground in forests and at their edges, near or under Douglas-fir; often abundant on the West Coast.

Edibility: Edible.

Note: This common associate of Douglas-fir does not have the reddish-brown cap of the matte jack (S. lakei). The names S. caerulescens and S. ponderosus have been assigned to different extremes of what seems to be a single variable species. One striking cold-weather variant has a dark green or greenish-stained cap. See MD 496-497 and plate 117.

Tamarack Jack (Suillus grevillei)

Other Names: Larch Bolete, Larch Suillus, Suillus elegans.

Key Features:

1. Cap dark red to reddish-brown in one form, golden-yellow in another.

2. Surface of cap slimy or sticky when moist, bald.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface pale yellow to yellow or olive-yellow.

4. Stalk solid, the lower part not staining blue or green when cut.

5. Stalk surface without resinous spots.

6. Veil present, at first covering the pore surface, then usually forming a ring on stalk.

7. Associated with larch (tamarack).

Other Features: Medium-sized; underside of veil yellow and sticky or slimy before breaking; stalk pale yellow at first, reddish or reddish-brown with age; spores olive-brown to dull cinnamon-brown.

Where: On ground or moss in woods or bogs near larch, often in droves; common wherever larch occurs, from the eastern slope of the Cascades north to Alaska and east to Montana.

Edibility: Mediocre.

Note: This attractive bolete tends to have a reddish-brown cap when growing with western larch and a golden cap when growing with tamarack (eastern larch). Exceptions and intergradations occur, however. (Larch is a deciduous northern conifer whose needles grow in rosettes of 10–20.) See MD 497 for more information.

Hollow-stemmed Tamarack Jack (Suillus cavipes)

Other Names: Hollow-foot, Hollow-stalked Larch Suillus, Boletinus cavipes.

Key Features:

1. Cap brown to reddish-brown (or occasionally yellow-brown).

2. Surface of cap covered with small fibers or hairy scales, not sticky or slimy.

3. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface pale yellow, yellow, or olive-yellow.

4. Pores arranged in more or less radiating rows.

5. Lower part of stalk hollow, at least at maturity.

6. Stalk not blueing when cut and rubbed.

7. Veil present, at first covering the pore surface, then disappearing or forming a slight ring on stalk.

8. Associated with larch (tamarack).

Other Features: Medium-sized; veil white, often leaving remnants on edge of cap; pores usually running down stalk; stalk yellow above ring, brown below, without resinous spots; spores olive-brown to dull cinnamon-brown.

Where: On ground in woods and bogs near larch, usually in groups; common wherever larch occurs, from the eastern slope of the Cascades north to Alaska and east to Montana.

Edibility: Edible but hardly incredible.

Note: The cap is not slimy as in the tamarack jack, and the hollow stalk is distinctive. Fuscoboletinus ochraceoroseus (MD plate 123) is a similar larch-loving bolete with a pinker or redder cap and dark reddish-brown spores. See MD 494–495, 506-507, and plate 122.

Matte Jack (Suillus lakei)

Other Names: Lake’s Bolete, Western Painted Suillus, Boletinus lakei.

Key Features:

1. Cap covered with reddish, reddish-brown, or brick-red fibers or small scales.

2. Underside of cap with a sponge layer; pore (sponge) surface yellow to yellow-brown or ochre when fresh.

3. Stalk solid within, staining blue or blue-green (often weakly) when cut and rubbed, especially near base.

4. Stalk surface without resinous spots.

5. Veil present, at first covering pore surface, then disappearing or forming a slight ring on stalk.

6. Associated with Douglas-fir.

Other Features: Medium-sized; cap dry to the touch, or sticky only beneath the hairs and scales; pores sometimes arranged in radiating rows, staining brownish or reddish where bruised; stalk yellow above ring, usually streaked with red or brown below; spores olive-brown to dull cinnamon-brown.

Where: On ground in forests and at their edges and along roads or trails, always near or under Douglas-fir; widespread and common wherever Douglas-fir occurs.

Edibility: Edible.

Note: In the Rocky Mountains and Southwest, this is the only species of Suillus commonly associated with Douglas-fir. In California and the Pacific Northwest it often grows with the fat jack, which has a smoother, stickier cap. See MD 495 and plate 124.