11 Epilogue: Berlin as a City of Reconciliation and Preservation

Alle freien Menschen, wo immer sie leben mögen, sind Bürger dieser Stadt West-Berlin, und deshalb bin ich als freier Mann stolz darauf, sagen zu können: “Ich bin ein Berliner!”

All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of West Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words “Ich bin ein Berliner!”

—John F. Kennedy, June 23, 19631

A city is a text with many pages, and every page counts. Too many pages are missing from Berlin’s urban history.

—Renzo Piano, architect2

Contemporary Berlin embodies many of the themes related to monumental preservation that I have explored in this book: how and when to preserve heritage; how to document the past; how to memorialize people and events; how to address the cultural genocide that was inflicted upon millions of people prior to and during World War II; and what gets preserved and what does not.3 Perhaps, most significant of all, Berliners are showing us that how to preserve defies a single solution. Rather, in Berlin as in elsewhere, there are many approaches to preservation.

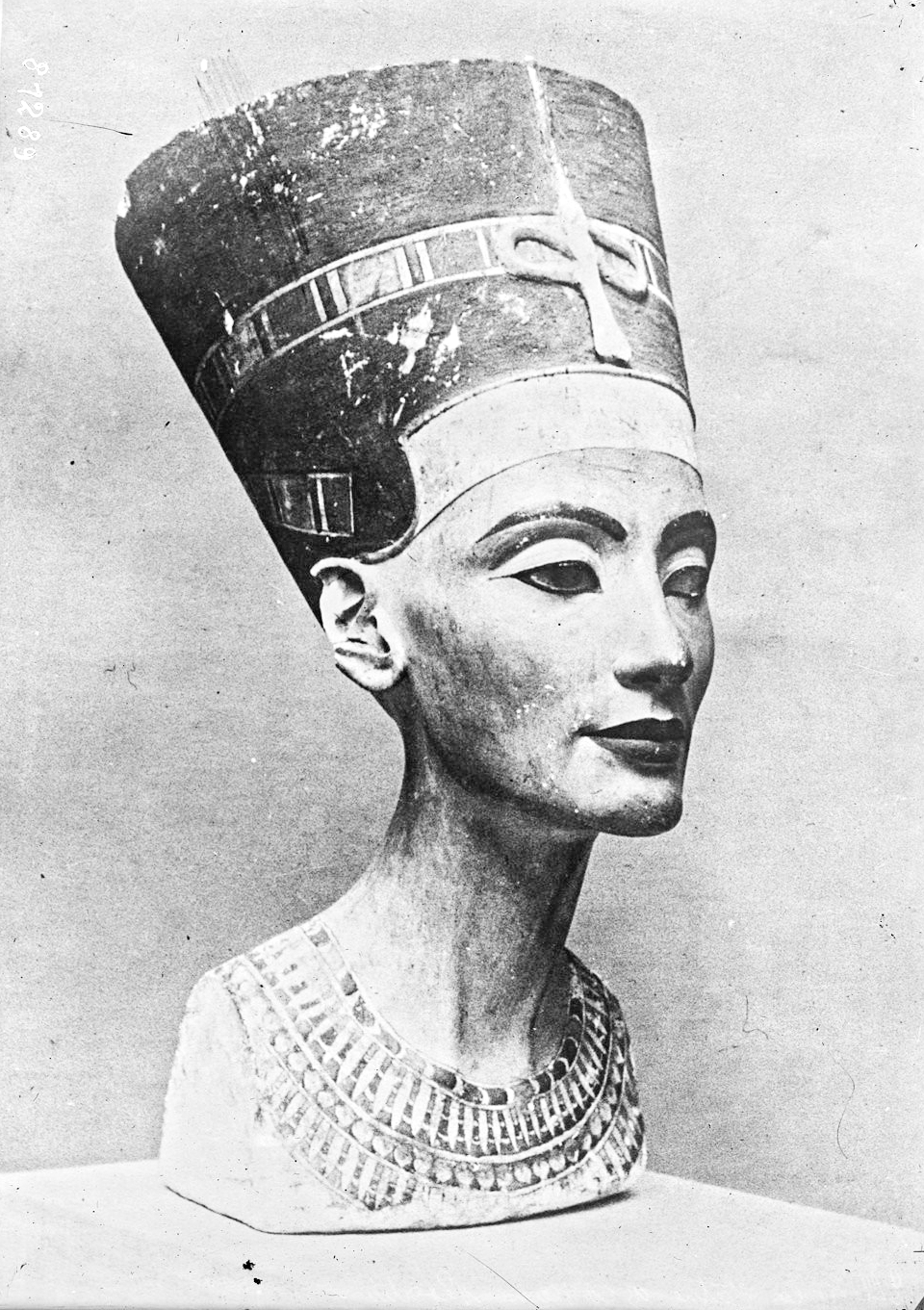

Berlin has some unique challenges—for example, what it means to preserve the history of a once-divided city. It also faces an issue of growing attention in cultural heritage institutions in countries of former colonial powers: what to do about ancient objects that they acquired and that are now contested. For example, Berlin continues to face ownership claims related to Nefertiti, one of its most famous cultural heritage objects (figure 11.1). (Her image appears on German postcards and stamps.) After the ubiquitous Berlin bears and the Brandenburg Gate, she is the city’s most famous icon. The Egyptians maintain that she was taken out of their country under false pretenses, while the Germans assert that she was obtained from the Egyptian government legally (more on this subject to follow).

Bust of Queen Nefertiti. Photograph, Rol Agency, France. Courtesy of Europeana

As rich and nuanced as all of these topics are, there is another aspect of Berlin that makes Nefertiti relevant to this study: Berliners are thoroughly engaged with preservation. As I suggested in chapter 1, with the preservation schema (figure 1.1), the role of the public has become increasingly important to successful projects. As will be seen in Berlin, seemingly every memorial, every teardown, every rebuilding, elicits passionate public response. In 2003 I visited the site of the future “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe” (Holocaust-Denkmal). It was a large, mostly bare area filled with trenches, surrounded by a chainlink fence on which people had hung and taped hundreds of notes with all kinds of opinions and observations about the memorial—positive, negative, indifferent, and irrelevant. Clearly, residents (and probably also visitors) were deeply engaged in this memory project. This shows that residents and tourists throng to construction sites to observe their goings on. There is currently a structure known as the “Humboldt Box” in front of the construction site of the Berliner StadtSchloss (also called Berlin Palace Humboldt Forum, or Humboldtforum) that includes a viewing area (along with exhibitions and tours). According to the website http://humboldt-box.com/, Humboldt Box is “one of the city’s most visited attractions.” The tradition of creating viewing stations in construction areas probably started during the rebuilding of the Potsdamer Platz in the 1990s. In 2001, Svetlana Boym described Berlin as “a Museum of conceptual art.”4 These vehicles for participation exist alongside the usual forums: the press and other media, casual conversations on the streets, protests, exhibitions, social networking, and so forth. Preservation inheres in this city, and it exists in a realm of people, residents and visitors, who, in one way or another, want to be involved. This underscores one of the persistent themes of this book: that preservation cannot take place as an isolated activity. In saving objects, buildings, sites, ideas, and cultures, we must be keenly aware of the human element—the things that impact people’s lives.

Berlin was founded nearly eight hundred years ago in 1237, though the past two hundred years are most germane to our preservation “tour” of the city. It was once the capital of Prussia as well as the largest city in the German empire. An Academy of Arts was founded in 1696, followed by an Academy of Sciences in 1700. When the French occupied Germany in 1806, Napoleon Bonaparte’s armies made off with many of Berlin’s works of art. Beginning around 1810 plans were drawn up for a public museum collection; Berlin gradually established itself as a museum leader. Prussia’s first public museum, the Altes Museum, opened in 1830 and housed paintings and sculptures.5 A decade later, the Neues Museum was created for cultural objects. Museums continued to be founded in the area known as Museumsinsel (Museum Island) until 1930; they showcased some of Berlin’s spectacular acquisitions, such as the Pergamon Altar, the Ishtar Gate, and the aforementioned Nefertiti bust, along with many other Egyptian artifacts that were once housed in their own museum and are now in the Neues Museum. Other museums sprang up in the city as well, including the Dahlem Museums complex, which once housed the Nefertiti bust.

Prussia’s defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 led to the modernization of Berlin, which was economically and culturally enriched by the outcome of the war.6 The 1911 entry on Berlin in the Encyclopaedia Britannica noted that “in no other [city] has public money been expended with such enlightened discretion.” By the end of the nineteenth century, as a cultural hub Berlin could have been favorably compared to London and Paris. In fact, when it came to acquiring foreign art, Berlin often competed with them. Kathryn Gunsch, for example, describes how in 1898 reliefs acquired by the British in Benin City (today in Nigeria), wound up in Berlin.7

Two world wars would greatly change Berlin—and the world. (Here our focus is on cultural heritage—not on the wars themselves.) Germany was first a perpetrator and then a victim of art plundering. Under the Nazi regime, Jews were stripped of their German citizenship, and their art collections, libraries, and personal papers were confiscated for Adolf Hitler. At the same time he ordered so-called “degenerate” art and books to be destroyed and their artists and authors to be deported. Later, using a network of Nazi agents, Hitler took artworks of his liking from across Europe for his collection. He was inspired by a 1938 trip to Italy to rebuild Berlin on a grand scale that would reflect his monumental ambitions. Similarly, he wanted to turn Linz, Austria, a city near his birthplace, into a cultural capital with a major art museum—the Führermuseum.

“His” art objects were cataloged and stored in several locations, including air raid shelters, remote castles, and salt mines. Hitler created sketches of his intended museum and cultural complex. Architect Roderich Fick created models for the doomed complex.8 The postwar disposition of the many thousands of hidden artworks was complex; objects continue to be rediscovered. Some items were looted, some returned to their rightful owners, and some—which rightfully belonged to Germany—were later returned there.

Much of Berlin was bombed, and many artworks that belonged to the museums were destroyed or severely damaged. After World War II Germany was looted by the Allied forces. As with Hitler’s collection, many of the Berlin museum objects were never returned to Germany. The plunder was revenge for Germany’s wartime activities, but there were also people who stole art for their own personal gain. No matter the cause of the plunder, stolen objects continue to be discovered. Additionally, claims continue to be made by survivors of the families whose artworks and libraries were confiscated by the Nazis.

Some objects that were damaged during the bombings of Berlin survive as memorials to the war. In the Bode Museum there is a small room of damaged statues—burn victims—from the Allied bombings of May 1945. The large wall panel describes the bombings:

The Second World War unleashed by Germany in September 1939 not only led to the damage and destruction of many of Berlin’s museum buildings [sic]. It also resulted in an inferno for a large part of the museum’s holdings. Between the 5th and 6th of May as well as between the 14th and 18th of May 1945, two devastating fires accompanied by explosions broke out in the main tower of the anti-aircraft bunker in Friedrichshain, which was one of the main evacuation sites for artworks belonging to the Berlin museums. The causes of this catastrophe, which occurred days after the surface air-raid shelter located in a public park had been surrendered to the Soviet armed forces, have never been satisfactorily explained. It resulted, however, in the greatest destruction and damage of art works [sic] in European museum history.

Like many other artworks exhibited in the Bode Museum, the three Italian sculptures on display in this room were recovered from the rubble of the devastated Friedrichshain bunker. They were initially transported to the USSR as looted art and then returned to Museum Island in 1958 along with many other objects belonging to the Berlin museums. More or less damaged, they are expressly presented here in a location whose appearance, with the exception of the wall coverings, corresponds to the time when the museum was built. Exhibited here with all their “wounds,” they are cautionary reminders of the effects that irresponsible human events have had on the world’s cultural heritage.9

One example in the Bode room is this Italian bust (figure 11.2). The Germans continue to maintain a list of Beutekunst (looted art)—the thousand or so missing objects that were confiscated by the Americans, Russians, and other Allied forces. The Germans persist in trying to recover their lost objects. The Museumsinsel is testimony to the highs and lows of German history. Itself now historic, in 1999 UNESCO added Museumsinsel to its list of World Heritage Sites. It is also decaying; nearly two billion euros have been spent on the renovation of the Museumsinsel since 1992.10 (Burned objects are displayed at other museums in Berlin as well, including the Musikinstrumenten-Museum, which has a case of burned instruments—with no captions. The wounded instruments speak for themselves.)

Italian bust at the Bode Museum, damaged in the May 1945 bombings. Image by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

Berlin has many other preservation stories to tell. I have selected a few.

The Reichstag

The Reichstag (the Parliamentary Building) was designed by Paul Wallot, and built from 1884 to 1894 on land owned by Prussian Count Raczynski, who refused to sell it in his lifetime. The Reichstag was extensively damaged by a fire in February 1933; Marinus van der Lubbe, a Dutch communist, was executed the following year for allegedly setting the fire. He may or may not have been involved in the arson; he was posthumously pardoned in 2007. Some sources claim that it is more likely that Adolf Hitler had the fire set as a way to persuade parliament to pass the Enabling Act—which greatly increased Hitler’s power.11 The Reichstag was also bombed during the war. It remained damaged and uninhabitable for more than fifty years before it was restored and reconstructed. The German flag was raised on top of the building as part of the German reunification celebrations in 1990; in 1991 the Deutscher Bundestag (German Parliament) voted to return the seat of the German capital to Berlin. Parliament has convened there again since April 1999.

Artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude created Wrapped Reichstag in 1995. The project was conceived in 1971, but took many years to bring about. The wrapping material was a silvery polypropylene fabric that captured the contours of the building. The many photos of it on the Web show the large number of spectators who were drawn to it. The Reichstag remained wrapped for two weeks and the materials were subsequently recycled. The wrapping project was a gift to the Germans. (See http://christojeanneclaude.net/projects/wrapped-reichstag for details of the project.)

Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s work celebrates impermanence, and their Wrapped Reichstag seems now to have been a set piece for an urban stage on which permanence versus impermanence has been the running show for the past thirty years.

Soon after “the wrapping,” architect Norman Foster reconstructed and redesigned the Reichstag building (1994–1999). Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s installation was a symbolic handing over of the building to Foster. The lengthy process of coming up with a plan for the new parliament that all the German decision makers could agree to is well described in Deyan Sudjic’s biography of Foster.12 The use of glass for the dome was intended to symbolize transparency in government as well as public accessibility. The wrapping project, in its modern (1990s) context, suggested that the building would be handed over—like a wrapped gift—to Foster, and that his work would lead to the building’s being handed over to the country. These activities have become part of the permanent record of the Reichstag, preserved in the documentation of the project. Appropriately, tourists flock to the Reichstag. The dome affords a beautiful 360-degree view of Berlin (figure 11.3).

The dome of the Reichstag. Image by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

Brandenburger Tor

The Brandenburg Gate, perhaps the best known of Berlin’s monuments, is in the middle of the Pariser Platz, just across from the Reichstag. The gate was designed by Carl G. Langhans and completed in 1789. Perched on top of the gate is the Quadriga, a twenty-foot-high sculpture of a laurel-crowned goddess in a chariot pulled by four magnificent horses. It was designed by the sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow in 1794. The gate and Quadriga, based on ancient Athenian temples, speaks to the aspirations of the Prussian rulers in their German empire. Perhaps it is not a stretch to say that its near-destruction at the end of World War II symbolized the end of the Nazis—a regime that went too far in its quest for power. The many images of the Tor attest to its changing “stature” before and after the two world wars, and before and after the Berlin Wall (figure 11.4 and 11.5). It has been restored to its former magnificence, and it is a tourist magnet. As it is situated only steps away from several monuments, it is a metaphoric preservation gateway. Its history is a powerful metaphor for the many meanings of monumental.

Brandenburg Gate, ca. 1958. “Soviet soldiers stand before Berlin’s historic Brandenburg Gate, with its newly restored Quadriga statue on top. The statue was returned to the gate in June 1958, replacing the Soviet flag that flew there for years after the closing off of East Berlin. From the booklet ‘A City Torn Apart: Building of the Berlin Wall.’ For more information, visit the CIA’s Historical Collections page.” From https://www.flickr.com/photos/ciagov/8048135673

Brandenburger Tor today, 2017. Permission of Barbara G. Preece, photographer

“Memorial Way”

The Tor and the Reichstag are surrounded by memorials. Directly in front of the Reichstag is the installation “De Bevölkerung,” (“To the People,” or “To the Population”) by Hans Haacke, in reference to the nearby inscription on the portico of the Reichstag, “Dem Deutschen Volke” (“[To] the German People”), which was placed there in 1916. By removing the word Deutschen, Haacke suggests that Berlin’s population is broader than just German people. And perhaps he also seeks to remove the historical stench of the Third Reich, which resulted in widespread death and destruction. Directly next to it is the “Memorial to the Murdered Members of the Reichstag,” which commemorates the Social Democratic and Communist delegates who were murdered by the National Socialists. It was designed by Dieter Appelt, Klaus W. Eisenlohr, Justus Müller, and Christian Zwirner. This piece also distinguishes itself from the Reichstag’s neoclassical portico and majestic Corinthian columns by presenting us with dark, jagged cast-iron plates, the antithesis of the classical. The very structure of the Reichstag can be seen as having once belied order and reason. The jagged stones beckon us to recall the dark history of the government between 1933 and 1945. Each plate contains, along the top edges, the names and birth and death dates of those who were murdered. The memorial can be extended if new names are discovered (figure 11.6).

Memorial to the Murdered Members of the Reichstag. Photograph by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

Directly across the street are several large panels one of which has a quotation by the former Federal Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt: “The Nazi dictatorship inflicted a grave injustice on the Sinti and Roma. They were persecuted for reasons of race. These crimes constituted an act of genocide.”

The panels offer a chronology of the genocide. Behind the fence on which the panels are attached, and at the edge of the Tiergarten, stands a reflecting pool: “Memorial to the Sinti and Roma of Europe Murdered under National Socialism.” Around the edge of the pool is the poem “Auschwitz,” by Roma poet Santino Spinelli. Triangular stones surround the pool, their shape suggesting the badges worn by concentration camp prisoners. In the middle of the pool is a triangular stone onto which a fresh flower is placed daily. The memorial was designed by Daniel (Dani) Karavan and opened in 2012.

Around the corner from the Sinti and Roma Memorial is a Memorial to Heinz Sokolowski (1917–1965), who was killed while attempting to escape over the Wall from East Berlin. This memorial looks rather makeshift: a tall, crude brown wooden cross with a photo of Sokolowski’s body at the center. Behind the brown cross are white crosses with the names of others who tried unsuccessfully to escape the DDR. The memorial was put up in 1966, just a few feet away from the Berlin Wall. The fact that it is nearly contemporary to Sokolowski’s murder makes it particularly effecting. It stands out in contrast to its neighboring memorials, which were planned for years and designed by prominent artists and architects (figure 11.7).

Memorial to Heinz Sokolowski. Photograph by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

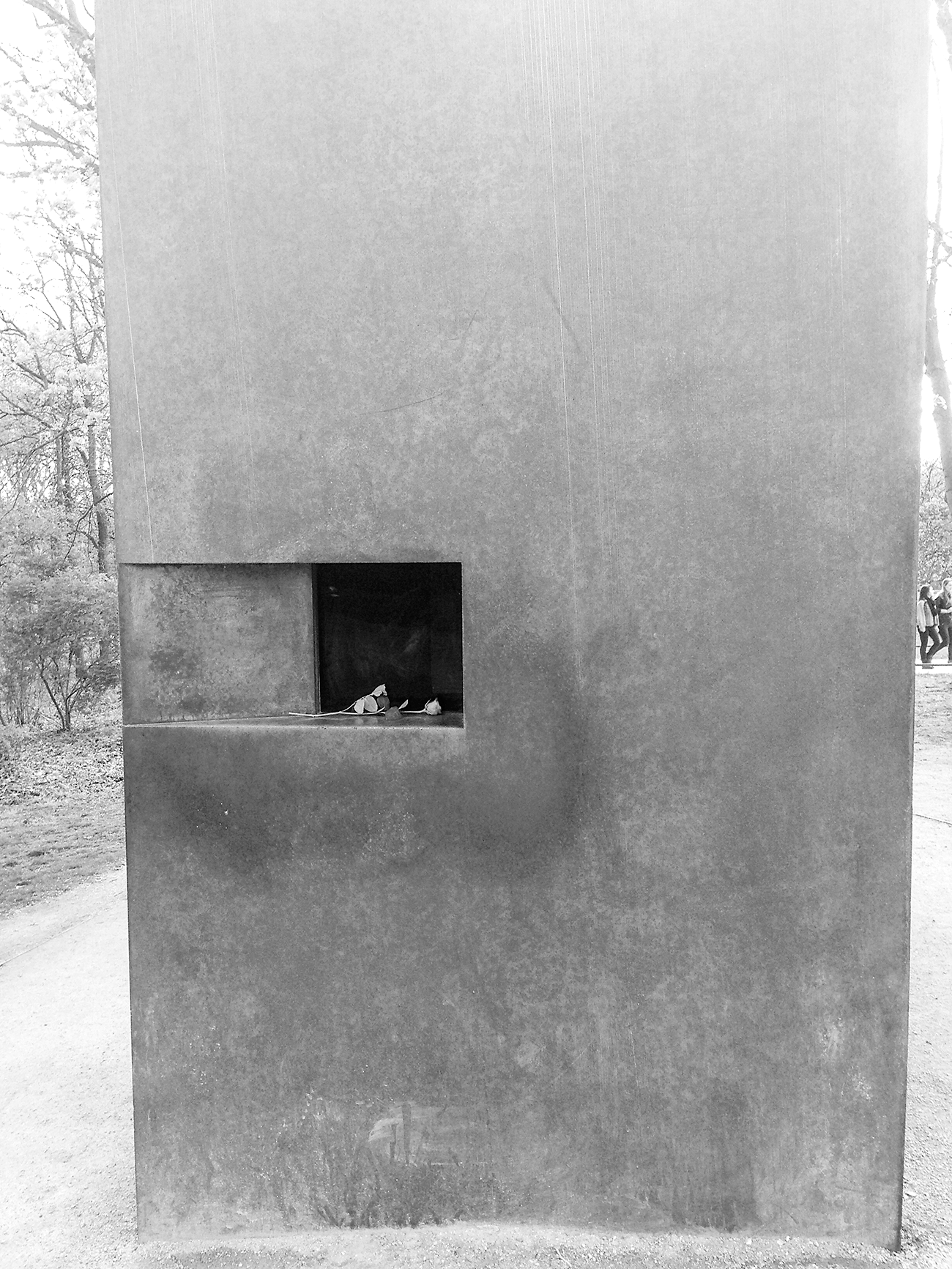

Close to the Sokolowski tribute is the Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted under Nazism, a small structure designed by Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, the pair of artists whose work Powerless Structure appears in chapter 1 (see figure 1.8). The memorial was built in 2008. During World War II, as many as 15,000 gays13 were deported to concentration camps where many of them died. At the street-side entry to the memorial is a long information board that informs us that some 50,000 homosexuals were convicted and sentenced to prison; “Lesbian women, too, were forced to conceal their sexuality. For decades, gays continued to be persecuted and prosecuted in both German post-war states and the homosexual victims of National Socialism were excluded from the culture of remembrance.”14 Efforts to establish a memorial to persecuted gay men and women began in 1992, at the same time as efforts were afoot to create memorials for the Sinti and Romas and the Jews. In 2002 the German Bundestag adopted a resolution to rehabilitate the victims of National Socialism and in 2003 it was decided to create a memorial. (See figure 11.8.)

Memorial to Homosexuals (the image is projected on the inside), and exterior view, with rose. Photographs by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

Figure 11.8 (continued)

The Holocaust-Denkmal, “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,” which I described visiting earlier in the chapter, is the largest of the major memorials situated near the Reichstag. It consists of 2,711 large concrete stelae situated on an undulating concrete field that is spread over 4.7 acres. It was designed by Peter Eisenman and Richard Serra (who later pulled out) and completed in December 2004. The stelae represent the Jews who were murdered by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945. The memorial seems to reside under the watchful “eyes” of the American Embassy directly behind it, and the Reichstag two blocks further north, as can be seen in figure 11.9. The scale of the site is supposed to reflect the scale of the genocide; some six million Jews were murdered.

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. Photographs by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

Figure 11.9 (continued)

At the beginning of this chapter, I noted how each of these memorials was conceived of and created with extensive discussion and debate. While the notes from 2003 that were posted at the construction site of the Holocaust-Denkmal expressed a diversity of opinions, they were just one manifestation of the seventeen-year debate over the memorial. As Peter Schneider, chronicler of Berlin, described it:

[The debate] was passionate, wild, ambitious, banal, highly philosophical, grotesque and magnificent. There was no argument that wasn’t made during the course of this debate, and none that wasn’t just as quickly refuted.… Jewish intellectuals explained that they didn’t need the memorial and considered it completely superfluous or even harmful; others claimed that it was long overdue. Some non-Jewish spokespeople agreed with the former group, others with the latter.

Schneider further describes the three questions at issue: first, whether a memorial was needed, and second, would centralizing memory in Berlin detract attention from the concentration camps? The third question was whether the memorial should be dedicated to the Holocaust’s Jewish victims only, or include other persecuted groups. This last debate was resolved by the creation of other group-specific memorials.15

Once the decision was made to create a memorial site specifically for the Jewish victims, an equally diverse number of opinions was expressed about its design. How large should the memorial be? Should the monumentality of the crimes be reflected in the memorial? Proposed designs ranged from incorporating freight cars of the sort used to deport the Jews to creating a brick smokestack that would continually put out smoke. Still another proposal was to build a bus station from which buses would go to concentration camps and other sites of Jewish persecution.16 In the end, Peter Eisenman and Richard Serra came up with the winning design.

Many views have been aired about the completed memorial. In Schneider’s eyes, it is successful. He feels that the site blends in with the city’s landscape and that it doesn’t force a sense of guilt on visitors. Not everyone agrees. In an essay that is critical of the memorial, Richard Brody observed:

The title [of the memorial] doesn’t say “Holocaust” or “Shoah”; in other words, it doesn’t say anything about who did the murdering or why—there’s nothing along the lines of “by Germany under Hitler’s regime,” and the vagueness is disturbing. Of course, the information is familiar, and few visitors would be unaware of it, but the assumption of this familiarity—the failure to mention it at the country’s main memorial for the Jews killed in the Holocaust—separates the victims from their killers and leaches the moral element from the historical event, shunting it to the category of a natural catastrophe. The reduction of responsibility to an embarrassing, tacit fact that “everybody knows” is the first step on the road to forgetting.17

Brody implies that a memorial in and of itself is not necessarily an effective way to preserve history. Such sites must contain more context. While there is an underground information center, Brody does not believe that it is adequate. A look at some of the other sites in Berlin illustrates the many ways in which preservation can be viewed.

The Jewish Museum Berlin is another site of Jewish remembrance. One particular installation, Menashe Kadishman’s Shalechet (Fallen Leaves) gives museum visitors a sensory experience of loss (figure 11.10). The following quote is from the Jewish Museum’s website:

Detail of Shalechet (Falling Leaves), 1997–2001 by Menashe Kadishman (1932–2015). Courtesy of the artist. Collection Jewish Museum Berlin

Visitors are encouraged to interact by walking on the exhibit itself: to see the open-mouths in terror, the faces of soundless screams; and to listen to the jarring clanging sounds when thick metal pieces jostle against other pieces.

It’s an eerie atmosphere with the installation all to myself. I also feel what is unmistakably guilt as I tread on the “screaming” faces. Am I walking over representations of living breathing [sic] people? I think these feelings are in fact necessary, that I need to have these feelings of loss. Something important has been taken away. It’s as if the sculpture asks: “Germany is presently incomplete—will the country ever heal and be complete again?”18

Potsdamer Platz

Potsdamer Platz looks like a new place. (Though certainly not like just any place because sections of the Wall are situated throughout.) Not long after the Wall came down, major construction projects began such as the Sony Center, the Arkadin, and the skyscrapers of the Potsdamer Platz. The area had originally been a dynamic city center and the busiest traffic intersection in Europe in the 1920s19—but most of the buildings were destroyed during World War II. The neighborhood eventually became something of a wasteland after the Berlin Wall went up because the East Germans tore down most of what had survived the war. Even buildings on the West Berlin side of the Platz were razed. There was a great demand to rebuild this part of Berlin once the Wall came down. With all of its shops, theaters, and restaurants, and because of its location near the old Checkpoint Charlie, this part of Berlin is once again lively (figure 11.11).

Sections of the Berlin Wall. Photographs by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

Figure 11.11 (continued)

Shortly before the fall of the Wall in 1989, the CEO of the Daimler Group purchased fifteen thousand acres southwest of the Potsdamer Platz. His plan was to construct the Quartier Potsdamer Platz, with Renzo Piano as the architect. There were two impediments to building there: the marshy ground below, and the old Weinhaus Huth, a building that had been designated a landmark in 1979—solely because it had survived World War II and the subsequent demolitions in the area. It stood in the construction site area. The Daimler project manager decided to engage the press and the public into this enormous (and enormously complicated) project by inviting them as regular visitors to the operational headquarters, where a red information box was constructed as a viewing station. This was successful and may have led to later such efforts to include the public in building and restoration projects—like the Humboldt Box mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. The culmination of the PR activities for the Quartier was a concert at the 1996 groundbreaking with Daniel Barenboim conducting Beethoven’s Ode to Joy while nineteen construction cranes moved their steel arms in time to the music.20 The Weinhaus Huth has managed to fit in with its new neighbors.

On the other side of the Potsdamer Platz, the new Sony Center faced its own historic preservation challenge. The complex was designed by Helmut Jahn, a German-American architect. It is a spacious and light-flooded structure that has a large, suspended oval roof. However, Jahn needed to incorporate the ruins of the Kaisersaal, all that was left of the old Hotel Esplanade. According to a city guide: “The Senate of Berlin stipulated that Sony should preserve the ‘Breakfast Room’ and the ‘Emperor’s Hall’ of the Grand Hotel Esplanade, both protected following the destruction in World War II [figure 11.12]. Accordingly, in 1996, the rooms were moved—1,300 tons were loaded onto wheels and shifted by 75 m (246 ft.) during the course of the week.”21

Kaisersaal at the Sony Center. Photograph by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

The juxtaposition is strange; the Kaiseraal is encased in a glass box, perhaps to “match” the glass office tower next to it. Still, it looks rather as if it was plunked down on the site, a visitor from another planet. Is this historic preservation? In the literal sense it is; but it is now a building without context. On the other hand, the entire Potsdamer Platz is a modern re-creation of a neighborhood destroyed by war and the city divided by the Wall.

And what has happened to the Wall? Everything. Within a year after it began to come down on November 9, 1989, most of it had disappeared. Some of it was ruined during the takedown. Other parts were taken by tourists and scattered around the world. Still other sections were sold off. Some sections remain in the city, and there is a display of part of the Wall near the Wall Memorial on Bernauer Strasse. Pieces have also been refabricated and newly decorated.

As with all of the other memorials, there were many opinions about what should happen to the Berlin Wall. Some people who had to look at the Wall for many years wanted it taken down completely. Others felt that there needed to be a memorial, a reminder of Berlin as a divided city. Museums and memorials are scattered around the former city borders, which shows that Berliners have made a widespread, permanent record of the Wall by placing pieces of it in prominent places throughout the city.

It is difficult to memorialize anything so soon after an event. That is a lesson about preservation that Berlin has had to grapple with over and over again. Still another: can a city have so many memorials and yet retain its vibrancy?

Yes it can. And one example is in the Kurfürstendam (see figure 11.13).

Kurfürtendam, the “Ruined Church.” Photograph by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

One of Berlin’s most visible “mementos” of the destruction of World War II is the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtnis-Kirche (aka “the Ruined Church”) in the Kurfürstendam, or Ku’damm, neighborhood. The Neo-Romanesque church was built in 1895, in honor of Wilhelm I, and was bombed in 1943. The ruins have been retained as a memorial. Originally, the church was to have been torn down for safety reasons. However, in a referendum, Berliners voted to preserve it, and the decision was made to build a new church next to it. Designed by Egon Eiermann, the new church was constructed from 1957 to 1963. The ruin is an arresting reminder of World War II, yet perhaps it is life-affirming as well. The Ku’damm is a lively neighborhood filled with shops, restaurants, and galleries. There is new construction under way around the church, a constant reminder that life goes on.

Another memorial worth mentioning is Hiroshimastrasse, because it reminds us of the international dimensions of war and peace. This little street is quite a contrast to the visible memorials all over Berlin (figure 11.14). It is in the Embassy district of Tiergarten and dates from 1862, when it was first named Hohenzollernstraße. In 1933 it was renamed Graf-Spee-Straße. In 1990 the street was renamed again after the first atomic bomb to fall on Japan. The Japanese Embassy was on the street during the Nazi era. When Berlin once again became the capital of Germany, the original embassy building was restored.22

Hiroshimastrasse. Photograph by Michèle V. Cloonan, April 2016

Akira Kibi describes the street’s current name:

The cool Hiroshima breeze can blow in any corners of the world connecting people with the wish of what Hiroshima stands for: the survival of human species and the respect for Nature. Such an idea already has some following: Berlin has a street, named Hiroshima Strasse, and the history of how this street came to be named after Hiroshima is very interesting, as told by Professor Mizushima of Waseda University.

Mr. Heinz Schmidt, a German school teacher who has visited Japan three times since 1965, made a bold proposal of changing the name of a park near his house in Berlin from its original name to Hiroshima Park. This attempt did not bear fruit the first time Mr. Schmidt tried it, in September of 1985, but his ardent effort continued for four years and it was paid off: he succeeded in converting the name of a bridge and a street that had until then been named after a Nazi Naval Admiral (those names represented Hitler’s policy in 1933, to change names of every localities [sic] into militaristic names) into Hiroshima bridge and Hiroshima Strasse. His proposal passed the Berlin municipal assembly in April 1989, six months before the fall of the Berlin Wall. The street and the bridge were officially welcomed as legitimate member [sic] of the locales of Berlin in September, 1990; the moment Hiroshima’s message gained its universality beyond national borders. The street just happens to run in Berlin connecting [the] Japanese embassy and that of Italy, resulting in the residential designation of current Japanese embassy as being at the number 6 [sic] of Hiroshima Street.23

The naming of this area after Hiroshima suggests, perhaps, that Berlin is becoming an international city of peace and reconciliation. In other words, the process of creating memorials has transformed the city from one in which the past is actively remembered to one in which that past can be transcended.

Demolition versus Reconstruction

One site in Berlin whose demolition was debated for years was the massive Palace of the Republic, the seat of the parliament of the German Democratic Republic in East Berlin. The complex was also a cultural center. The building was opened in 1976 and demolished from 2006 to 2008, so that the land could be used for a reconstruction of the Stadtschloss (also known as the Schloss [castle]). The demolition was opposed by former East Berliners as well as others who felt that this building was an important part of Berlin’s history. Before demolition began, the building became a temporary center for art exhibitions and other events. The argument for tearing the building down was that it was filled with asbestos—though that ultimately caused the demolition to be extremely time consuming and costly. (One positive outcome was that 35,000 tons of steel were sent to Dubai where it was used to build the Burj Khalifa.)

What makes this demolition unusual is that the Stadtschloss—torn down by the East Germans in 1950—is being completely reconstructed from old plans, photographs, and other renderings. The Schloss was struck by Allied bombs in 1945 and lost its roof. Although it was damaged, the building was still structurally sound and it could have been restored. However, the East Germans probably viewed it as the ultimate symbol of Prussian imperial rule and thus wanted it destroyed. (Hitler saw it as “un-German” and never used it.)

The Schloss was first built in 1433, and it was modified over the centuries. Its history was tightly interwoven with Berlin’s. Proponents of the reconstruction made the case that Berlin and the castle were one, while opponents pointed out some of its negative associations, like the fact that Kaiser Wilhelm II had declared World War I from its balcony, or that on November 9, 1919, Karl Liebknecht proclaimed the new German Socialist Republic. (Of course “negative” depends on one’s own political beliefs. These two examples illustrate the many manifestations of the Schloss.) Others feared that the new castle would be an architectural pastiche. That it was also the center of the Revolution of 1848 may have swayed some. What may have convinced still others that the reconstruction would be beneficial is that the new palace would integrate the various buildings in the historical center of Berlin, which includes Museum Island, Berliner Dom, and the Lustgarten.

Schneider discusses Wilhelm von Boddien, who learned about the destruction of the Schloss when he was a student and who spent decades marshalling support for reconstructing it. In a story that is typical of preservation initiatives in Berlin, von Boddien found a unique way to garner support for reconstructing the castle: he commissioned French artist Catherine Feff to create a trompe l’oeil of the Berlin Schloss on more than one hundred thousand square feet of canvas. The canvas was mounted on scaffolding, to give “the illusion of a resurrection.”24 The effect was supposed to have been particularly striking at night, and the beautiful image seemed to have turned disbelievers of the reconstruction project into believers.

Construction of the new Schloss began in 2012; it is to be completed in 2019. The Berliner StadtSchloss will become the Berlin Palace Humboldt Forum (Humboldtforum), a global center for art and culture. This is one of the many “faces” of preservation—reconstruction—but not from the “leftovers” of a ruined building. It is actually not preservation at all in the strictest sense. With books and documents we can talk about facsimiles, which are generally copies made directly from originals. The Schloss is a copy, but made from original plans. Such an approach is a “re-creation” because the impetus is to bring something back. In this case it is the experience of the original castle.

Nefertiti and James Simon

At the beginning of this chapter I mentioned the Nefertiti bust that the Egyptians want back. She was discovered in 1912 at Tell al-Amarna by the German archeologist Ludwig Borchardt, in the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose (fl. 1350 B.C.E.). The Germans and Egyptians divided up the finds, but French officials were responsible for antiquities, even though Egypt was under British administration at the time (see chapter 4). Gustave Lefebvre was the Frenchman in charge. Borchardt may have concealed the value that he knew the Nerfertiti had. The bust went to Berlin where it was held in private hands until it was first displayed in the Neues Museum in 1924. It remained there until 1939, when Berlin museums were closed and their objects moved to secured spaces for safekeeping. Nefertiti was again moved and then found by the American army in 1945; she was then shipped to an American collecting point in Wiesbaden. The bust moved again, before being sent to West Berlin, where it was displayed at the Dahlem Museum. Then it was moved to the Egyptian Museum in Charlottenburg until 2009, when it was returned to the Neues Museum.25 (It is nothing short of a miracle that the bust has survived so many moves and two world wars.)

Lefebvre’s successor, Pierre Lacau, in 1925 set in motion the restitution claims that have continued. While he admitted to Lefebvre’s mistake, he asserted that the Germans had essentially pulled a fast one. Nefertiti’s “past” recently came to light again for two reasons: in 2011 the Egyptians called for its return, and in 2012 filmmaker Carola Wedel made a documentary about James Simon, the Jewish philanthropist who was one of the founders and financers of the Deutsche-Orient-Gesellschaft (German Orient Society). He had financed the excavation at Tell al-Amarna. Simon had been nearly forgotten in Germany despite his incredible largesse to German cultural institutions. He died in 1932, and because he was Jewish, his memory was expunged until recently.

Now, a new museum is being built on Museum Island in Simon’s honor, and information about his collections is displayed in the Bode Museum. He connects back to Nefertiti in a fascinating way. He became the owner of the Nefertiti bust after the 1912 excavation, but he donated it to the Egyptian Museum of Berlin in 1920. However, he was willing to return the bust to Egypt in return for other artifacts from Egypt, believing that the restitution would ensure further excavations. The Egyptians have not given up hope that Nefertiti will return to Egypt. But it will not be likely to happen in the near future.

Rory McLean, an essayist who has written about Berlin for years, observed:

That Germany is open and dynamic today is a consequence of taking responsibility for its history. In a courageous, humane and moving manner, the country is subjecting itself to a national psychoanalysis. This Freudian idea, that the repressed (or at least unspoken) will fester like a canker unless it is brought to the light, can be seen in Daniel Libeskind's tortured Jewish Museum, at the Holocaust Memorial and, above all, at the Topography of Terror. Be aware that this outdoor museum, built on the site of the former headquarters of the SS and Gestapo, is not for the fainthearted.26

Sometime in the near future, Berlin will address the preservation needs of its now large—and growing—multicultural population. Perhaps the city can draw on its many experiences to date. Public engagement will continue to be a foundation for preservation efforts.

* * *

I conclude this volume with this snapshot of Berlin. It is merely a snapshot, since it cannot tell the full story of this city’s history, its rises and falls and subsequent rises, its attempts to rebuild itself after more than one (and more than one kind of) demolition, and its relationship to the theme of this book. Berlin’s complexity as a city with a long and glorious (and also an inglorious) past—as a melting pot of peoples and ideas and embarrassments and victories and failures and destruction and reconstruction and transformation—raises a host of key questions. In no particular order: How long after a cataclysm should a city begin to rebuild itself? When a city has had many pasts, and when it is destroyed, which of its pasts do those who want to rebuild it choose? Should the city be rebuilt following past models or should it emerge with a fully new face? If part of the city’s past reveals its inhumanity, its viciousness, and its embarrassments, whom should we follow: those who want to rebuild the city and hide those shortcomings or those who want to ensure they are remembered? What kinds of memorials should a city have? How revealing should they be? Who should decide these things? And who should pay for the reconstruction and memorialization? We must remember that preservation is not merely of the built and natural world, it is of memory and emotion. And both kinds of preservation come with costs. There are many other questions like these that speak to preservation.

Berlin represents a host of issues I have examined throughout this book. I chose to end with the preservation activities of this great city because the kinds of issues that Berliners are dealing with today mirror many of the issues that we have looked at across these chapters. Tearing down buildings harkens back to the Richard Nickel chapter. The effects of war remind us of the chapters on Syria and cultural genocide. And even the difficult choices of what to save and what not to save are touched on in chapter 2, in my discussion of the sculptures of Soviet-era figures. In fact, nearly all of the themes covered in this book could in one way or another be related to Berlin.

What better place than Berlin to demonstrate all the ways in which preservation is monumental.

Notes