Although quantitative analyses and statistical manipulations are useful, a lot of what we infer relies on more subjective assessments and comparisons. This is frequently because we don’t have the information required for more vigorous approaches. For better and for worse, the great need for large, long-term studies of the original collections leaves a lot of scope for future research. Since this work has yet to be done, the following observations are not based on detailed analyses, but we think they are nonetheless interesting. We have tried not to fall into the cherry-picking trap of considering only those items that exhibit the characteristics helpful to our theory. We look at not only tangible evidence, such as artifact forms and signs of the heat treatment of materials, but also less tangible evidence, such as artistic expression and behaviors like caching large bifaces. We also consider cases in which a lack of evidence (about burial practices, for instance) might be meaningful.

End scrapers are common in Upper Paleolithic, Paleo-Indian, and many other archaeological assemblages around the world. In fact, they were probably the most common type of formal stone tool in Late Stone Age hunting and gathering cultures. Generally speaking, they are highly standardized, and the shape of their working edge is greatly influenced by its function, which is usually hide working. Nevertheless, their forms and method of manufacture do vary among archaeological cultures.

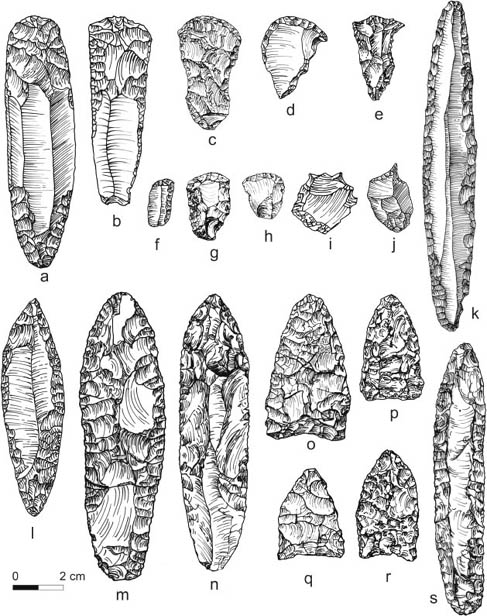

FIGURE 7.1.

Comparisons of Solutrean, pre-Clovis, and Clovis lithic tools: (a) Solutrean end scraper made on a blade; (b) Clovis end scraper made on a blade; (c) Southeast Early Paleo-American (proto-Clovis) end scraper made on a blade; (d) Solutrean spurred end scraper; (e) Clovis spurred end scraper; (f) Solutrean microscraper; (g) Early Southeast proto-Clovis microscraper; (h) Clovis microscraper; (i) Clovis graver; (j) Solutrean graver; (k) Solutrean retouched blade; (l) Solutrean plane face point; (m) Southeast Early proto-Clovis plane face point from the Johnson site; (n) Southeast Early Paleo-American plane face point from Florida; (o) Solutrean indented base point; (p–r) Early Mid-Atlantic Paleo-American indented base points; (s) Early Southeast Proto-Clovis steeply retouched blades.

Nearly all the Paleolithic assemblages we have examined have end scrapers, made on either flakes or blades, and for the most part their forms are not distinctive. Those produced by unifacial percussion or pressure flaking that extends up over much of the dorsal surface of the scraper blank are an exception (figure 7.1a–c). This flaking style is present in only French Solutrean and the earliest North American Paleo-Indian assemblages. In fact, these are called Solutrean scrapers in the French tool typology, which considers them, like laurel leafs, a diagnostic type.

Does this mean that the same type of end scraper is a normal product of the general flaking technology, especially pressure flaking, and not really distinctive? This is unlikely, because many Beringian and post-Clovis flaking technologies include both biface manufacture and pressure flaking but lack this form of end scraper. Thus, it appears that this trait may be the result of technological continuity.

The second distinctive type of end scraper has a different style rather than a different flaking method. It is called spurred because it exhibits small well made sharp points on one or both corners of the working edge (figure 7.1d–e). These spurs are the product of intentional pressure flaking and should not be confused with scrapers that have incidental points on their corners. Some of the intentional spurs are fine enough to be used as gravers, but their purpose is unknown. These scrapers were frequently made on biface reduction flakes.

Spurred scrapers are characteristic of most Paleo-Indian and Solutrean tool kits but are rare to nonexistent in Beringian and other Upper Paleolithic assemblages. They do occur in the Mesa lanceolate point assemblage, which was introduced from the south and is not part of the western Beringian technology, making it unsurprising that the Mesa tool kit would include this scraper form. Are spurred scrapers another link between Solutrean and Clovis? We think they may be.

A third distinctive form is the microscraper, which is found in Solutrean (figure 7.1f), pre-Clovis (figure 7.1g), and Clovis (figure 7.1h) assemblages. These are basically the same as other end scrapers in proportions and configuration, but they are less than 3 centimeters long. They seem to have been intentionally made small and not the result of resharpening. In the French Upper Paleolithic these forms first appear in Solutrean assemblages, and they are absent from Beringian assemblages.1

Gravers have very small, sharp projections flaked on a thin flake or blade (figure 7.1i–j). It is unclear what they were used for. Gravers with single and multiple projections are present in Solutrean and Clovis assemblages, but they are absent from the Dyuktai/Denali collections. Like the earliest spurred end scrapers, fine point gravers first appear in Beringia at the Mesa Site and are also associated with lanceolate and fluted projectile points that likely had their origins in the south.

A hallmark of early Solutrean assemblages is the plane face point (figure 7.1l–n). These are primarily unifacial and are found in varying proportions throughout Solutrean times. They also appear in the New World. One was found at the Johnson Site in Tennessee (figure 7.1m). This artifact was seemingly made from a blade and produced with intent, and it displays the typical manufacture technology of Solutrean plane face points. Another specimen was found near Rum Island in the Santa Fe River, Florida (figure 7.1n). It was not recovered from an in situ context, but Clovis and pre-Clovis artifacts, also not in situ, were in its immediate vicinity. This point was also made on a blade (blades are not found in post-Clovis assemblages in Florida) and conforms to Solutrean technology.

Another important artifact type is the indented base point from northern Spain, some southern French Solutrean sites, and pre-Clovis sites in eastern North America. We noted in chapter 5 that the Spanish Solutrean points were made with a distinct technology that was probably strongly influenced by the unavailability of easily flakable stone. These are relatively small points, some of which are unifacial but many of which are fully bifacial (figures 5.10 and 7.10). Even the points that are considered unifacial are often partially bifacial, especially at the tip and base. Indented base points from pre-Clovis contexts are usually fully bifacial, although some are partially unifacial. Like the Spanish Solutrean points, the earliest pre-Clovis points were made with a combination of percussion and pressure flaking (figure 7.1p–r). Many of the Spanish Solutrean and pre-Clovis indented base points are similar in size, form, and manufacturing technology. It should not escape our attention that Clovis points have indented bases. In addition, while the incidence of unifacial Clovis points is low, they do exist, and although some were expedient forms, hastily made on flakes, others, like Solutrean examples, are well made (figure 2.6b–c, i).

As our pre-Clovis point sample continues to expand, we are beginning to see developmental trends in sizes and technologies. Spanish Solutrean (figure 5.10) and Cactus Hill/Miller points are small and subtriangular (figures 4.2, 4.3a–b, and 4.4d). The later Jefferson Island, Page-Ladson, and Suwannee point styles range from small to larger sizes more typical of Clovis forms (figure 4.10a–c and m–p). Although fluting occurred only in the Western Hemisphere, some Spanish Solutrean points have significant basal thinning that may presage fluting technology (figure 5.10f–h). In addition, the first incidence of an end-thinning flute scar on an unfinished point preform is seen in the 21,000-year-old Miles Point pre-Clovis assemblage (figure 4.4e). By the time of the Johnson Site occupation, flintknappers were experimenting with significant basal thinning on nearly completed bifaces (figure 4.11, b, d and f). It isn’t possible to get an idea of success rates from this assemblage—completed points would have been removed from it after manufacture—but there were clearly a lot of errors, as one would expect in the development of this risky flaking method. It appears that Solutrean flintknappers in northern Spain developed the technique of basally thinning projectile points, perhaps only to remove the center ridge of a blade. However, the advantage of a concave-based point is for ease of hafting to a spear or harpoon. The bottom line is that there is a chronological, typological, and technological continuum from the earliest indented base points in southern France and northern Spain to the inception of fluting technology in eastern North America.

FIGURE 7.2.

Laurel leaf bifaces: (a) Fourneau-du-Diable southwest France; (b) Cinmar Site, obverse, reverse, and cross section; (c) Aquitaine region of southwest France.

Thin leaf-shaped bifaces with well-controlled percussion thinning flake scars on both faces, common in many Solutrean assemblages, have been found in the Mid-Atlantic region of North America. The geologic context of the North American specimens indicates that they overlap in time with their Solutrean counterparts. Both Solutrean and early North American laurel leafs have non-invasive percussion retouch along the distal margins, which seems to be a by-product of resharpening and, along with edge dulling and the scarcity of impact breaks on many of the medium to large specimens, leads us to think that they served as knives. Pressure burin fractures—the loss of flakes from the tip of a blade pressed against a resilient object such as tight skin or bone—common on the tips of many Solutrean laurel leafs are also indicative of knife use (figure 7.2c).

We have focused our attention on bifacial technologies for our comparisons of flaked stone assemblages, but the manufacture of other specialized flake and blade forms can be equally complex and variable. With the exception of Mike Collins’s discussion of Clovis blade technology and detailed analyses of some of the non-Solutrean Upper Paleolithic blade and microblade technologies in Eurasia, relatively little attention has been paid to this aspect of flaked stone technology.2

Although there are almost unlimited ways to produce blades, bladelets, and microblades, two basic approaches were used in the assemblages in this study. The first was production from natural unmodified stones or flakes, with little or no core preshaping. This is typical of bladelet technologies, whose process is much like that of generalized flake production except that the removals are spaced and sequenced so that many of the flakes are elongated (at least twice as long as wide). This approach was used in the northern Spanish Solutrean sites; the pre-Clovis sites of Cactus Hill, Miles Point, Meadowcroft, and Oyster Cove; some Clovis sites; and some Beringian assemblages. A lack of high-quality or large enough raw material may in some cases have heavily favored the selection of this method: expedient bladelet production is common where coarse quartzite and other grainy-textured pebbles and cobbles make up the majority of available materials. It is of course difficult to determine whether the technology was a response to the raw material or the stone was selected because it suited a traditional bladelet technology.

Bladelets and microblade technologies found in the Solutrean, pre-Clovis, Clovis, and various Beringian technologies were frequently created with the same form as a blade wedge-shaped core, but smaller (figure 7.3a–c).3 In some cases, especially in northern Spain and on the East Coast in North America, the production of bladelets was heavily influenced by the predominant availability of mainly poor-to-medium-quality small raw material. There are also bladelet cores in Clovis and Solutrean sites where large high-quality raw material was available, but these often seem to be the result of large blade core reduction rather than a separate bladelet technology.

The second basic approach to the production of blades and microblades is to shape the raw material into a suitable form, or precore, before blade production begins. Two different strategies are visible in our assemblages: preparation of a single core face for blade removal and complete precore shaping by the production of a thick biface (see chapter 1 for a discussion of these techniques). The latter is widespread in the early and late Upper Paleolithic assemblages in southwestern Europe. Most cores from these technologies end up with a remnant bifacial ridge on the back, opposite the main blade-producing surface. The same basic strategy was used in the production of microblade cores in Beringia, but most of the microblades themselves were produced by pressure.

FIGURE 7.3.

Bladelet and blade cores: (a) Solutrean bladelet core; (b-d) pre-Clovis bladelet cores; (e) face and top view of Solutrean polyhedral blade core; (f) face and top view of Clovis polyhedral blade core; (g) face and side view of Solutrean wedge-shaped blade core; (h) face and side view of Clovis wedge-shaped blade core.

The Solutrean is the only assemblage in Upper Paleolithic southwestern Europe with precores prepared with single bifacial ridges and flat, often unmodified backs. The resulting cores regardless of form do not have bifacial back ridges.

Two large blade production strategies were shared by Solutrean, pre-Clovis, and Clovis knappers, resulting in different core types: wedge-shaped and conical. Conical cores have a single platform and unidirectional blade removals (figure 7.3d–f). Wedge-shaped cores have a single primary platform and mostly unidirectional blade removals (figure 7.3g–h). Occasionally a blade would be struck from their distal end, but this seems to have been done to correct flaking errors rather than systematically to produce the desired blades. Intentional bi-directional flaking from opposed platforms occurs in some Solutrean assemblages. This technique was also common in earlier and later technologies in Eurasia; however, Solutrean cores are the only ones with flat backs.

The wedge-shaped cores in Clovis sites were produced with the same techniques as the Solutrean cores and are unlike those made by any of the cultures in Beringia or any other European Upper Paleolithic culture. The technology of the conical blade core forms in Clovis has been reconstructed in detail, and these forms resemble Solutrean examples and some blade cores in sites less than 13,000 years old in the Russian Far East and Alaska.4

Our knapping experience with unidirectional blade technologies indicates that many of the blades they produce are slightly to moderately curved, well suited to the production of the scrapers and other unifacial blade tools found in Solutrean, pre-Clovis, and Clovis assemblages.

A comparison of Solutrean, pre-Clovis, Clovis, and non-Clovis blade dimensions indicates that most of the Solutrean blades in our sample fall into the same metric range as Clovis, as do the specimens from the pre-Clovis sites in the Chesapeake Bay area. The large quartzite blades from Cactus Hill and from northern Spain group together but are still within the range of the Solutrean-Clovis continuum. Post-Clovis blades from Texas and New Mexico fall outside the range of the earlier blades.5 All of these are significantly larger than the early blades (microblades) in Beringia. Some blades in the Russian Far East, the earliest of which are of Clovis age (figure 3.3g), are a possible exception.

Although North American researchers have not generally reported tools made from blades with pressure-flaked retouched edges (called backed blades), these do appear in Clovis assemblages. Backed blades and used bladelets have been found at the Gault Site in Texas, the Bostrum Site in Missouri, and the Paleo-Crossing Site in Ohio.6 A backed blade with flat pressure flake scars on the ventral face and a blade with an abruptly beveled truncated distal edge were found at Jefferson Island (figure 4.10f–g).

Heat treatment of stone to enhance its flakability is a sophisticated process that demands careful control and, if improperly applied, can result in significant wastage of stone. This procedure is especially useful where raw materials are intractable and flaking techniques include substantial biface percussion thinning or pressure flaking (including using pressure to produce microblades). Heat treating first appeared during Solutrean times in Europe, and although it is not often recognized, it occurs in pre-Clovis and Clovis assemblages. Two heat-treated side scrapers and an end scraper were found at the Lower Meekins Neck Site (18DO70), a Clovis site in Dorchester Country, Maryland.7 Heat treating is also reported at the Anzick Site in Montana.8 This may be another trait that links Solutrean and Clovis and excludes other early technologies, such as those found in Beringia, but its presence has not been sufficiently evaluated in many of the other assemblages (including pre-Clovis) to be certain.

Another cultural trait that seems to be distinctive of the Solutrean and Clovis cultures is their inordinate use of exotic types of stone for the manufacture of some of the more specialized flaked artifacts. Many archaeological assemblages of different periods include artifacts made of stone from non-local and at times far distant sources, and this can be a reflection of group mobility (figure 2.4). In Clovis and Solutrean assemblages the intentional selection of certain rare and exotic stone types seems to have gone well beyond expediency and mobility. Although it is likely that Clovis people, especially in western North America, were highly mobile and would have encountered rare and exotic stones during their travels and explorations, their focus on certain types, especially quartz crystal and red fine-grained stones, is noteworthy. It is also clear from the Clovis caches that high-quality exotic materials were preferred for many of the oversize, possibly ritual, pieces. Exploitation of these rare sources also demonstrates Clovis knappers’ intimate knowledge of the geography of vast territories. The special selection of exotic materials by Solutrean knappers is even more remarkable: whereas Clovis knappers had untapped or at most lightly used resources to choose from, Solutrean people lived in areas where knappers had been exploiting stone sources for tens of thousands and even hundreds of thousands of years. Yet there is a clear selection during the Solutrean for rare and exotic materials, especially quartz crystal, chalcedony, and jasper.

Did these intentional selections of exotic stones, especially quartz crystal, represent an expression of aesthetics? Were the artifacts made from special raw materials perceived to hold symbolic value or power? Although this type of cultural behavior might arise independently, its presence in Solutrean and Clovis assemblages and absence from the other early assemblages in our study is striking.

To date, a purposeful selection of exotic raw materials has not been identified in the pre-Clovis assemblages in eastern North America. This could be used to argue against the Solutrean–pre-Clovis–Clovis continuum, but the samples are as yet very small. The one possible example of exotic material selection could be at Meadowcroft, where Flint Ridge stone was present, although this could be the result of mobility rather than special selection. The pre-Clovis flintknappers at Miles Point used locally available stones, perhaps indicating that they had not yet explored enough of the interior to find exotic sources. By contrast, at the Jefferson Island occupation, just a few miles from and thought to be several thousand years later than Miles Point, all of the artifacts are made of raw materials from more distant sources. This indicates that the Jefferson Island people explored the interior and found better stone sources than what was available in their immediate area.

Bone, ivory, and antler artifacts are scarce in late Pleistocene sites, especially those exposed to weathering or in acidic environments. This includes most of Beringia and eastern America except Florida, and only to a lesser extent western America and southwestern Europe. Nevertheless, some of these artifacts have been recovered.

The most abundant bone tool assemblages are from the caves and rock shelters in southwestern France and northern Spain. Although some artifact types occur in diverse archaeological cultures, others seem to be restricted to specific periods. Bone, antler, and ivory points are the most common, and the most abundant type are known as sagaies. These are rods that taper to a sharp point at one end and have a single bevel at the other. Sagaies vary in cross section, size, and proportion throughout the Gravettian, the Solutrean, and into the Magdalenian in southwestern Europe but are most abundant during the Solutrean. A split-base style distinctive of the Aurignacian drops out during the Gravettian (figure 5.1e–f). The simple sagaie form is retained in the Magdalenian but is supplemented with a wide range of styles, many of which have multiple carved barbs.

Virtually identical sagaies have been recovered from nearly a dozen fluted point sites, most in western North America, where soils are neutral to slightly basic, and from areas in northern Florida where waterlogging has favored their preservation. Although the association between the Florida pieces and fluted point assemblages is tenuous, the fact that most of these sagaies were made from fresh mammoth ivory places them in the fluted point era (or earlier). Not only are a large sagaie from a Solutrean level in Laugerie Haute in southwestern France and another from northern Florida virtually identical in form and size but both have zigzag decoration just above the bevel (figure 7.4c–d). If they had been found near each other we would be debating not whether they were from the same culture but whether the same person made them!

Other kinds of bone, antler, and ivory tools found in both Solutrean and fluted point sites include sagaie-like implements with rounded tips that probably preclude them from being projectile points. They could, however, have been foreshafts that were part of composite, harpoon-like weapons. The rounded, tapered tip could have been inserted into a flanged, hollowed-out harpoon-like socket, into whose other end a stone point would have been set, similar to examples from the Arctic (figure 7.5). There are no hollowed-out sleeves that clearly date to Clovis times, but an example dated to circa 11,000 years old was found associated with extinct faunal remains in a peat bog in Indiana.9 We cannot be sure this specimen is a Clovis artifact, but we think it is just a matter of time before one is found in a clear pre-Clovis or Clovis context. Although not a true toggle harpoon, this weapon would have been effective in hunting sea mammals, especially during glacial times, when seawater was more buoyant, due to its relatively high salt content, keeping animals from sinking rapidly. The true toggling harpoon does not show up in Europe until Magdalenian times, when the inflow of massive amounts of freshwater from melting sea ice and glaciers diluted the seawater’s salinity.

FIGURE 7.4.

Projectile points made of bone or ivory (sagaie): (a) Solutrean; (b) Clovis; (c) Clovis with zigzag design; (d) Solutrean with zigzag design.

Several robust bipointed ivory rods were found in Culture Zone IV at the Broken Mammoth Site in Alaska (figure 3.7g–h). This zone dates to between 13,000 and 13,500 years old, and the ivory is dated to nearly 19,000 years old, suggesting that it was scavenged from an older, frozen mammoth. Similar artifacts have been found in Solutrean deposits, but these rods are simple forms, and their superficial resemblances do not necessarily indicate a common origin.

The famous mammoth bone shaft wrench from the Murray Springs Site in Arizona (figure 2.13m) and the perforated antlers found in Upper Paleolithic sites in France may have served a similar function. The wrench was used to straighten wooden shafts, such as spears, darts, and arrows. Frequently shafts were slightly bent, causing the weapon to wobble in flight. To straighten a shaft, a hunter would have placed it into the perforation of the wrench, twisted, and levered against the wrench. Even today, people who hunt with primitive wooden weapons frequently use a shaft wrench on a daily basis. When we showed a cast of the Murray Springs shaft wrench to French colleagues, they remarked that it was virtually identical to one found at a Solutrean site. This relatively simple form is not specifically Solutrean and has been found associated with other Eurasian assemblages. It is not, however, a type of tool identified in Paleolithic Beringia.

FIGURE 7.5.

Speculative reconstruction of a Clovis harpoonlike bone weapon system: (top) bone foreshaft from Anzick Site, Montana, and foreshaft socket from an Indiana peat bog; (middle) assembled foreshaft, socket, and Clovis point from Anzick; (bottom) side view of foreshaft inserted into foreshaft socket.

Finally, delicate eyed bone needles exist in both the French Upper Solutrean (figure 7.6b) and the Folsom collections (figure 7.6a and c). Clovis sites with intensive long-term occupations, where large-scale clothing and sewing activities would have been conducted, are situated in the east, where preservation is poor. Small bone items such as needles might be expected there but are absent, possibly because of acidic soils. One exception is Sloth Hole, a submerged wet site in northern Florida, where at least two purported unperforated ivory needle fragments have been recovered.10

FIGURE 7.6.

Comparison of bone artifacts: (a) bone needle from Idaho; (b) Solutrean eyed needle; (c) Folsom bone needle from Colorado; (d) Solutrean notched pendant; (e) Folsom notched disk; (f) front and side view of bone Solutrean atlatl hook; (g) front and side view of bone atlatl hook from Florida.

Western Clovis sites in areas with neutral to basic soils that provide relatively good conditions for preservation are kill sites and caches where only specialized activities were conducted, most not requiring the use of delicate tools like the eyed needle. One might expect to encounter needles at the campsites associated with kills, but so far that has not happened, presumably because those sites contain few artifacts and were used for very short durations. It is not until Folsom times, when we get large, longer-term habitation sites with good organic preservation, that eyed needles and other delicate bone artifacts become relatively common.

With the possible exception of some of the submerged assemblages in Florida, bone tools have not been found in pre-Clovis contexts.11 Once again, this may be partly due to sample size and poor preservation, and the inundated early sites might produce this evidence, if it exists. However, several ivory atlatl hooks, thought to be associated with Clovis or pre-Clovis artifacts, have been found at a site in the Santa Fe River (figure 7.6g). Among these are several made in the same style as Solutrean atlatl hooks (figure 7.6f). There is no evidence of the use of atlatls by Siberian Paleolithic people.

While our discussion to this point has centered on comparison of technological futures of stone and bone artifacts, other cultural behaviors found among Solutrean and Early Paleo-American cultures appear to link them into a historical relationship.

The Solutrean in France and northern Spain is well known as having an extremely rich artistic tradition, especially in cave paintings, such as those at Altamira. With the exception of a couple of possible Clovis pictographs of mammoths in the west, there are no equivalents in any of the archaeological cultures in this study. Art engravings on artifacts small enough to be transported as well as objects used for personal adornment exist in Solutrean and other western European Upper Paleolithic contexts.

A common feature in late Solutrean deposits is multi-notched bones, usually bone points notched on both sides. We also find small bone disks incised or notched around their perimeters (figure 7.6d). These disks could have had any number of uses, for instance as gaming pieces, counting or numeric devices, or simply art or objects of adornment. Although notched-bone objects have not been found in Clovis sites, similar bone disks are part of post-Clovis Folsom artifact assemblages (figure 7.6e), perhaps indicating the continuation of this Paleolithic tradition.

Engraved bones and stones also occur in Solutrean and Clovis assemblages, some with geometric designs, while others depict naturalistic images of animals (figure 7.7g). A mastodon figure etched on a probosidian bone fragment has recently been reported from Viro Beach, Florida (figure 7.7h).12 During the past several years incised flat limestone pebbles similar in size, shape, and to a lesser extent design to those in Solutrean collections have been found in Clovis contexts at the Gault Site in central Texas (figure 2.14). These Gault specimens are decorated with geometric designs, one of which depicts an over-and-under weaving pattern and another that has been interpreted as a running fox. The Gault Site also included a double-sided incised clast with a series of dart shafts with fletching (figure 7.7a), similar to stones from Polesini, Italy (figure 7.7b–e), and Parpallo Cave, Spain (figure 7.7f), where, as at Gault, a large number of incised stones have been found.13 A single incised slate fragment was encountered in the post-Clovis level of the Ushki Site in western Beringia, but this type of artifact has not been seen in eastern Beringia.

FIGURE 7.7.

Incised stones thought to show fletched spears: (a) obverse, side, and reverse views of Clovis incised stone from Gault, Texas; (b–e) Solutrean-age incised stones from Polesini, Italy; (f) incised stone from Solutrean level, Parpallo Cave, Spain; (g) Solutrean zoomorphic deer design; (h) engraved mastodon on bone from Viro Beach area, Florida.

The absence of cave paintings associated with fluted points or Beringian sites may be attributed to the scarcity of caves and shelters where they could have survived the ages or even been executed. This is especially true on the eastern seaboard and vast plain of the continental shelf, where caves would have been rare to nonexistent. In such an area, pebble engraving may have been a durable outlet for artistic ambitions, and the impetus for cave painting lost.

It may not have been just a matter of availability, however. The tradition of cave painting in Europe did not last past the end of the Pleistocene, even in areas where cave art had flourished in earlier times. Nobody can deny the existence of a thriving cave painting tradition during the Upper Paleolithic, culminating in the Magdalenian. But the operative word here is culminating. Why was this rich heritage abandoned by people who we believe were direct descendants in the same place? It had gone, even in the core areas of southwestern Europe, by the time the fluted point tradition developed in North America. If it died out in areas where it had flourished for thousands of years, why should we expect it to have been transmitted over long, caveless distances?

Personal adornment is associated with modern human beings and makes its appearance in western Europe during the early Upper Paleolithic, around 35,000 years ago.14 Various forms of beads and pendants are well represented in Solutrean sites. Most recognizable ornaments are drilled and perforated, but many other less obvious items may have served the same purpose. Similar objects have been recovered from sites in Beringia, but none more than 9,000 years old have been found in eastern Beringia.15 Neither beads nor pendants were found in the earliest levels at any of the pre-Clovis sites, but once again this may have more to do with preservation and sample size. It is clear that Clovis people made beads for personal adornment, although they are rare in the record. A bone bead preform was recovered at Blackwater Draw, New Mexico, and a stone bead was found near the Clovis point at Shawnee Minisink, Pennsylvania. At the larger western Folsom campsites, beads are part of the cultural inventory, but a drilled bone bead from the Shifting Sands Site in west Texas was so small it was recovered only because it was stuck to a Folsom artifact by a calcium carbonate crust and came loose after the stone tool was placed in a specimen bag.16

Extra-large, extremely well made bifaces have been found buried in groups, sometimes with other kinds of artifacts and frequently with concentrations of red ocher. This caching of extraordinary artifacts has been found in only two more-than-13,000-year-old archaeological cultures: Solutrean (figure 7.8a) and Clovis (figure 7.8b). For both cultures, researchers have suggested that some of the artifacts were made for non-utilitarian purposes and that their very manufacture held special symbolic and ritual meaning.17

In all of western Beringia there is only a single reported biface cache, so called even though the cluster of eight bifaces was found scattered around a small area in a final stage Dyuktai occupation level at the Tumular Site in the Aldan River Valley, Siberia.18 The bifaces in this cache are likely preforms for microblade cores and in any event not comparable to the caches of large bifaces found in Solutrean and Clovis contexts. They are not of special manufacture and probably represent provisioning behavior: leaving a collection of microblade precores for future retrieval. Two similar provisioning caches of precores have been reported from eastern Beringia, one at Onion Portage on the Kobuk River and other near Point Barrow.19 A radiocarbon date from the Onion Portage Cache suggests that both caches are likely post-Clovis in age.

FIGURE 7.8.

Oversize bifaces from caches: (a) Solutrean; (b) Clovis. Outlines show the extremely thin sections.

Remnants of shelters or structures have been described in western Beringia, specifically at Ushki Level VI. These take the form of shallow circular depressions, often with a fire pit near the center. Some artifact clusters in eastern Beringian sites have been interpreted as indicating outlines of former shelters.

Evidence of constructed shelters is absent from the Solutrean, but this is probably because most of the excavations have been in caves and rock shelters, where they were not necessary. Purposefully laid cobble floors found at early Magdalenian sites in southwestern France are, however, possible remnants of dwellings (figure 7.9a).20 These features consist of cobble pavements laid out in square or rectangular patterns measuring a few meters on each side. Some also exhibit small extensions in the center of one or more sides. Artifacts tend to be present in concentrations in and around the features. In addition, all but two are aligned with the cardinal directions.

FIGURE 7.9.

Comparison of structure pebble floors: (a) Lower Magdalenian, France; (b) Clovis/pre-Clovis, Gault Site, Texas.

The rectangular pebble floor at the Gault Site (figure 7.9b) is highly reminiscent of these European features. It measures about 2 by 2 meters, is oriented in the cardinal directions, and has a small portico square centered at the north end. Use-wear studies of blade tools found around this floor indicate that reed matting was manufactured here, perhaps for flooring or external coverings.21 To our knowledge this type of floor does not appear in other Paleo-Indian campsites and may represent a long-lasting European Paleolithic construction technique.

A distinguishing feature of Paleo-Indian sites is that their fire hearths were not stone lined. By contrast, many Solutrean fire hearths are lined with cobbles, although examples of unlined fire hearths were found in the lower Solutrean levels 4, 5, and 6 at La Riera Cave.22 It is probably not coincidental that these are the levels that produced all of the indented base projectile points found in situ, as well as exotic cherts, seal bones, and major accumulations of limpet shells and fish remains. This suggests that these levels represent temporary hunting camps used by people who were based on the coast and likely exploited the resources of the Atlantic Ocean. Their artifacts and camp debris are most comparable to the American pre-Clovis and Clovis camp situations. If Clovis descended from this branch of Solutrean peoples, perhaps unlined Paleo-Indian hearths were a continuation of the latter’s practice.

While it is difficult to use lack of evidence as evidence of a relationship, we must point out that no Solutrean or Clovis burials have been found. Unlike with other Paleolithic European, Siberian, and later North American cultures, which all have evidence of mortuary customs, we have no idea how the earliest Paleo-Americans or Solutrean people buried their dead. Both groups apparently used a form of burial that did not preserve the human remains. Their customs may have been similar to the historic scaffold type of burial, wherein the body was left in an open environment to facilitate transformation to another dimension. Some investigators think the remains of two individuals recovered at Anzick Site in Montana are associated with the Clovis artifacts there.23 However, radiocarbon dating of the human bones indicates that they were placed near the cache 400 or more years later.

The lack of human remains from both cultures renders it impossible to assess their paleo-genetic relationships.

We would be remiss if we did not discuss typical Solutrean artifacts that are not present in the New World. Given the changing environmental conditions and adaptations to these shifts during the time span represented by the Solutrean–pre-Clovis–Clovis continuum, it is no surprise that some tool types would fall out of favor and new types be introduced. The resulting differences among the assemblages can be as interesting and explanatory as the similarities.

Some Solutrean projectile point styles are absent from pre-Clovis and Clovis assemblages, including several varieties of shouldered points primarily defined by their method of manufacture, willow leaf points, and stemmed and corner-notched points.

In France, blade-based shouldered points occur in Solutrean deposits after 19,000 years ago. They exhibit unifacial pressure flaking, although many examples are partly flaked on both faces and some are completely bifacial. In northern Spain, Solutrean shouldered points were mainly made by limited, abrupt, probably anvil-supported percussion on blades. The conclusions of several studies, including replication and use experiments, are that they were used to tip projectiles, but whether for darts or arrows is still being debated.

If pre-Clovis and Clovis tool forms descended from the Solutrean, why are shouldered points absent from the former? There are several possible answers. First, it is common for some artifact types to drop out of a cultural inventory, especially but not necessarily if functional requirements change. Second, not all Solutrean assemblages include shouldered points. If the particular Solutrean people who eventually found their way to North America came from a group or groups that didn’t use shouldered points—perhaps, based on radiocarbon dates from the Chesapeake Bay sites, because they left Europe before the advent of this technology—one wouldn’t expect these artifacts in North American assemblages.

In some Solutrean sites several point types occur in the same occupation. Such a mix may have many explanations, particularly in an area geographically restricted for thousands of years like the Vasco-Cantabrian region. Different bands may have used socially identifiable, unique symbols such as point types and other markings, so middens with mixed types may be the result of such circumstances as cooperative hunting ventures or occupation by different contemporary groups operating in overlapping territories.24

Some French Solutrean sites have yielded a form of artifact called a willow leaf point. These resemble the finer pressure-flaked Solutrean shouldered points, but they lack the shoulder. To our knowledge these points have not been subjected to use-wear studies, but along with many of the thin laurel leaf points, they may have been used as knives. Again, this form developed late in the French Solutrean and may not have been in the inventory of the people who adopted a maritime economy and eventually traveled to North America.

Stemmed and corner-notched projectile points have been found in Mediterranean and Portuguese Solutrean sites. These weapon tips, thought by some researchers to be arrowheads, are not present in northern Spain or southwestern France, so there is no reason to expect Vasco-Cantabrian descendants in North America to have used them. Conversely, indented base points do not appear south of the Cantabrian Range.

In our hypothesis, technological innovations also occurred after people arrived in the New World. Even though many of the Spanish indented base points are basally thinned and a few might be classified as multiple fluted, we do not subscribe to the idea that there is an Old World antecedent of fluting technology. Fluting is not a common means of basally thinning bifaces in other times and places and is probably not a major technological advantage. It is unclear how and why it developed, and since it does occur in some pre-Clovis bifaces, we suspect that this particular technique was an American invention.

Small blades and bladelets were part of most Upper Paleolithic assemblages in western Europe. Some consider the paucity of backed bladelets in Clovis assemblages significant, but like shouldered points they are not universal in the Solutrean either. For example, at La Riera there are no backed bladelets in nearly a third of the lower occupation levels; moreover, 81 percent of the artifacts at La Riera came from occupation levels that did not contain any stone projectile points, and roughly 75 percent of them came from the two upper occupation levels.25 These data suggest that by later Solutrean times slotted bone or antler projectile points were the primary weapon tip for hunting in this upland setting.

Backed bladelets may have been part of a variety of items other than projectile points but were mainly used like razor blades and may have been inserted into slotted bone knives. Sagaies slotted for inset blades appear during the final stages of the Solutrean occupations of northern Spain, likely as a result of influence from other European Paleolithic technologies. Since slotted sagaies have not been found in any Clovis context, it appears that Solutrean people adopted this technology after the ancestors of pre-Clovis found North America, or in subgroups not directly related to the New World descendants. On the other hand, slotted sagaies armed with microblade insets became the dominant weapon technology in western Beringia long before any putative Clovis ancestors might have crossed the Bering Sea.

A burin is a tool created by striking a flake or flakes from the edge of an artifact to produce a sharp 90 degree edge for working hard substances such as ivory, antler, and bone. The edge fragment, usually triangular or square in cross section, that was removed to make the burin is called a spall. Although a few burins have been found in Clovis artifact assemblages, they are rare. A burin and a spall were found at Miles Point, and a burinated blade was recovered from Jefferson Island. A burin-like tool was also recovered at the Coats-Hines mastodon butchering site in Tennessee. By contrast, at La Riera Cave burins make up about 10 percent of the stone tools recovered from the Solutrean levels. They are also extremely common throughout the Siberian and Beringian Paleolithic cultures. Apparently, for some reason burins lost their importance and were dropped from Clovis technology, regardless of whether their Paleolithic origins were in Iberia or Siberia. However, burin-like tools that may have functioned in the same way have been recovered. These were produced not by edge removal but rather by radial breakage of thin, mostly biface flakes.26

Woodworking adzes occur in some Clovis and pre-Clovis sites but not in Solutrean or Beringian collections. We believe that this tool type has not been found in Solutrean assemblages because the sources of wood in the upland areas where Solutrean material culture has been defined were limited. Driftwood from North America that washed up along the coast would have been the only source of large timber for the Solutrean people. Consequently, evidence of adzes and other tools that may have been used to make boats or for other construction projects are now underwater.

The impression that the Solutrean and Clovis are separated by approximately 5,000 years is often cited as the fatal flaw of our hypothesis. Unless there exists a reasonable series of dated archaeological cultures with intermediate bridging technologies to fill the gap, like those before us who saw the similarities of Solutrean and Clovis technologies, we would have to consider the shared traits as independent inventions rather than historic relatives, whether related to Beringia or the Solutrean. The oldest of these bridging technologies would need to have artifacts that are nearly identical to the parent Solutrean technology, and the youngest should begin to closely match Clovis technology.

FIGURE 7.10.

Radiocarbon date ranges of the Solutrean, Mid-Atlantic Early Paleo-American, Southeast Early Paleo-American, and Clovis.

This is where the pre-Clovis evidence from the eastern United States fits in (figure 7.10). The radiocarbon date of the Cinmar mammoth indicates that the Solutrean-style laurel leaf biface associated with it may date to at least 22,760 years old (see chapter 4). The Cinmar age is consistent with the date of greater than 21,000 radiocarbon years before the present for the occupation of Miles Point. The artifact assemblage from Miles Point includes biface projectile points, blades, scrapers, and burins that are technologically close to artifacts found in Solutrean levels 4, 5, and 6 at La Riera Cave that date to 20,970±620 RCYBP. The 16,940±50 RCYBP date for the pre-Clovis occupation at Cactus Hill also overlaps with the dates of later Solutrean occupations of the Vasco-Cantabrian area of Spain. However, the pre-Clovis artifact assemblage from Cactus Hill does not include the late Solutrean inset bladelet technology. At Page-Ladson, dated to circa 12,388 RCYBP, and related sites such as Jefferson Island, we see the continuation of blade and burin technology, but the projectile point technology now includes larger, unfluted “Clovis-like” projectile points. At the Johnson Site in Nashville, Tennessee, early attempts at systematic basal thinning are evident, but the Clovis technique of platform preparation for fluting has not been perfected, and there is a high rate of failure during final fluting attempts (figure 4.11). The Johnson Site bifaces are associated with Solutrean-style artifacts including a plane face point (figure 7.1m) and Solutrean scrapers (figure 7.1a–c) and blades. This evidence suggests that Johnson was occupied by proto-Clovis people, provides a date for the development of techniques to flute Clovis points, and serves as a transition between early Mid-Atlantic Paleo-American and Clovis technologies.

The Cinmar date of 22,760 RCYBP pushes the presence of people in North America back to the time of the Solutrean culture. Clearly the chronological gap has been closed, and the high number of corresponding flaked stone and bone tool forms and technologies make a historical connection feasible.

We have compared the chronology, tool types, and technology of the archaeological remains in late Pleistocene Beringia, continental North America, and southwestern Europe in an attempt to identify historical relationships. When we had large enough samples of artifacts, we compared tool assemblages and flaked stone technology and submitted them to cluster analysis. This allowed us to see what assemblages clustered, how they clustered, and what distinguishing attributes determined the clustering.

Our cluster analysis distinguished between different types of sites in fluted point and eastern Beringian assemblages. However, it also indicated to us how inconsistently archaeologists have recovered, analyzed, and reported sites and assemblages over the past century. This is a major obstacle to investigating the origins of people in the New World, but our initial efforts show that some reasonable conclusions can be drawn.

Comparisons of less quantifiable aspects of the archaeological record, including rarely recovered artifact types and various behaviors, have shown strong similarities between the fluted point and Solutrean traditions and a near lack of correspondence between fluted point and early Beringian traditions. The Nenana Complex shows the strongest similarities with Clovis, but Nenana is at best contemporaneous with Clovis and significantly younger than early Mid-Atlantic sites, raising the question of which may have been derived from which. Based on the available data, we would argue it is likely that certain aspects of Nenana and the Arctic Paleo-Indian assemblages were derived from people to the south, perhaps related to a northern branch of Solutrean descendants, rather than the other way around.27

There are sufficient similarities between all of the circa 12,000-to-14,000-year-old archaeological cultures of eastern Beringia to suggest that they originated from the Upper Paleolithic microblade traditions of Eurasia. At the same time, in our opinion, the technological, behavioral, and dating evidence overwhelmingly support the theory that the fluted point traditions in North America derived from a regional and chronological variant of the Solutrean cultures of southwestern Europe. The only alternative, as opined by the archaeologist Gary Haynes, is to assume that the complex technologies of the fluted point traditions sprang out of an entirely alien Asian technology without transitional phases.28 As flintknappers and lithic technologists, we seriously doubt that such a scenario ever happened; complex technologies require developmental antecedents even if introduced by foreigners.29

Although we have used general Solutrean artifacts, technologies, and behaviors in this analysis, we think it unlikely that all areas where Solutrean culture existed were directly involved in the colonization of eastern North America. It is more likely that only one relatively small area within the Solutrean sphere contributed to this process. The best fit we can find for the site of pre-Clovis ancestors, considering both the artifact assemblages and the known environment at the time of greatly lowered sea levels, is the area adjacent to the Bay of Biscay, where the Pyrenees meet the sea. Here the ancient beach line would have been clear of ice at times and would have extended almost straight along the Celtic continental shelf to several hundred kilometers west of glacier-covered Ireland. In other words, we hypothesize that the people who brought Solutrean traditions into the Americas were from the modern Aquitaine of France and Vasco-Cantabria of Spain—the Basque areas of southwestern Europe, and perhaps more specifically the adjacent submerged areas in the Bay of Biscay.

We frequently hear the argument that the absence of a well-documented Clovis predecessor in northeastern Asia just means we have not found it yet. To us the problem seems to be not the lack of a good candidate but where that candidate is located. Our guess is that no one would question the Solutrean origin of Clovis if Solutrean sites were found in northeastern Asia instead of southwestern Europe.