Always, then, in this flotsam and jetsam of the tide lines, we are reminded that a strange and different world lies offshore.

RACHEL CARSON, THE EDGE OF THE SEA

The preceding chapters provide information that illustrates the strong correlations between Solutrean technologies of southwestern Europe and the earliest technologies found in eastern North America. There is a possibility that these could be the consequence of independent invention, but we have argued for a historic relationship. To consider this proposition further, we pose models of how and why a trans-Atlantic connection would have taken place.

Our hypothesis proposes that certain Solutrean groups expanded their terrestrial economic resource base to include maritime resources. Since the direct evidence of these maritime resources is mostly on the submerged continental shelf, the well-excavated Solutrean sites near the ice age coast in northern Spain provide the best clues for a maritime adaptation. Lawrence Straus and his associates have done some of the most recent and intensive excavations in this part of Spain. Their research on the Paleolithic occupation of La Riera Cave, in Asturias between Santander and Oviedo, has provided a springboard for the synthesis of more than a hundred years of Paleolithic archaeology in northern Spain. Moreover, they have published a wealth of data from which we can draw to build our models and hypotheses.1 Hence, we can examine their Vasco-Cantabrian reports for evidence pointing to a shift from a terrestrial to a maritime economy, or to a mixed economy that exploited both biospheres. Because of this wealth of data, our model is based on the continental shelf of the Vasco-Cantrabrian region, but the Solutrean people who we hypothesize came to North America could have originated from any place along the Celtic or even the North Sea continental shelf.

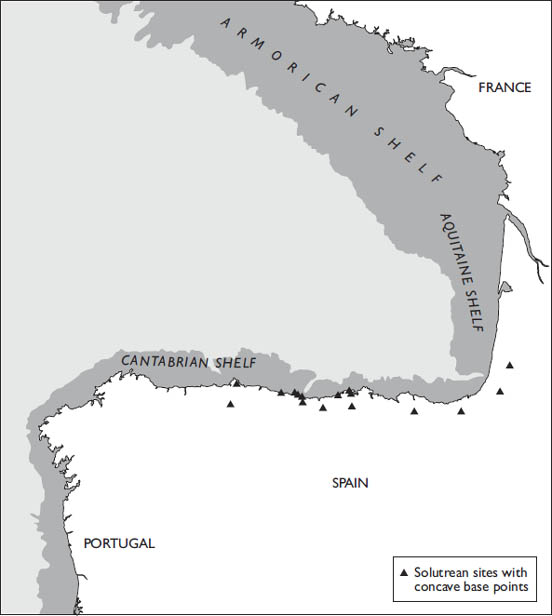

Approximately fifty-two sites in the Vasco-Cantabrian provinces of northern Spain have been identified as occupied during the Solutrean period (figure 8.1). They are distributed along a narrow coastal strip that is roughly 350 kilometers long by 50 kilometers wide, stretching from the Nalón River in Austurias to the Bidasoa River in Basque country, bounded on the north by the Bay of Biscay and on the south by the then glaciated Picos de Europa. This area was roughly 20,500 square kilometers when it included the now submerged continental shelf. Solutrean sites appear to be evenly distributed throughout the region but concentrated along river valleys within 37 kilometers of the ice age coast.

FIGURE 8.1.

Solutrean sites in northern Spain and adjacent southwest France. Triangles mark the Solutrean sites that have occupation levels where bifacial concave base projectile points were found.

The number of sites with known Solutrean occupations represents an approximately tenfold increase over the number of sites per millennium during the preceding Aurignacian and Gravettian periods. Geoffrey Clark and Lawrence Straus postulate that this increase reflects a growing human population as Iberia became a critical refuge for people who abandoned northern Europe during the climatic crisis of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM).2 People fleeing territories rendered uninhabitable by the advancing glaciers and deteriorating climatic and hunting conditions migrated south and west, mostly ending up at coastal locations where the marine environments slightly moderated the inclement weather. Since the Vasco-Cantabrian coast is a relatively small and confined area, such an influx of population would have stressed its subsistence resources and reduced the size of the territories available to resident groups.

Clark and Straus also postulate a trend during the Solutrean of intensified food acquisition and suspect that specialized hunting methods, such as game drives, surrounds, and ambushes, were perfected to procure large numbers of animals during single episodes of hunting. Hunters developed new technologies, such as decoys, nets, movable fences, thrusting spears tipped with self-barbed points, spear throwers, and even bows and arrows, allowing them to be more efficient in capturing and killing game. Although there is no direct evidence for most of these methods, we agree with Clark and Straus that there was a broadening of the kinds of animal and plant resources that were regularly exploited for food.

If the increasing number of archaeological sites signals a similar increase in human population density, requiring an intensification of hunting, tremendous stress would have been placed on the local animal populations unless major new elements were incorporated into the subsistence economy. As Straus and Clark have pointed out, increasing niche breadth by adding new kinds of foods to the subsistence base is another result of territorial circumscription.

Any long-term increase in human population also eventually requires reorganization of its distribution to maximize the use of the available resources. A free-ranging settlement pattern with bands exploiting large territories, shifting from one valley to the next when resources were depleted, would have given way to smaller, more prescribed, exclusive territories. Local groups would then have become more familiar with resources that free-roaming bands had neglected in favor of those with a higher payoff, such as simply following a herd of horses into a neighboring valley.

As the population density increased, there would also have been a parallel development in social relationships that relieved resource stress and provided better mechanisms for dealing with normal periodic shortfalls and those caused by environmental catastrophes. A set of related social groups could have monitored game over larger areas and, when one area experienced a shortfall, obtained relief from another group. Other advantages would have been more predictable sources for marriage partners and trading partners, to name a few possibilities.

The archaeologist Louis Binford has said that “if intensification is indicated by a shift in exploitation from one type of biotic community to another, the shift will usually be to aquatic resources.”3 The evidence from La Riera demonstrates that the Solutrean people did broaden their niche by including aquatic resources. The question is, did they include marine sources beyond estuaries and beaches?

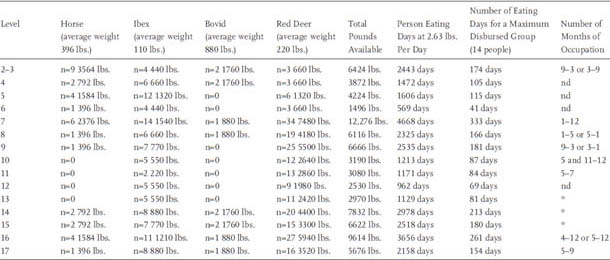

The stratigraphy in La Riera Cave provides an excellent picture of changing resource procurement strategies. The sixteen levels that contain artifacts attributed to Solutrean manufacture are thought to have been deposited between ca.18,000 and 20,500 radiocarbon years before the present. On the basis of the faunal remains, Straus and Clark suggest that the activities and types of occupations can be divided into three groups, from oldest to youngest: levels 2–3 were residential camps where bison and horse were the primary prey; levels 4–6 were temporary hunting camps; and levels 7–17 were residential camps from which red deer were intensively hunted.

A study of the faunal remains by Jesús Altuna provides more insight into the economic activities conducted in and around the cave, as well as the durations of occupation or at least the seasons when the cave was used.4 His interpretations are unfortunately based on minimal samples, since the entire site has not been excavated, some levels were more intensively excavated than others, and the kinds and amounts of faunal remains removed by earlier excavations and by relic hunters are unknown.

From a total of 20,105 bones excavated from the sixteen Solutrean levels, Altuna calculated a minimum number of individual animals (MNI) in each level by comparing the bones present with the expected number of kinds of bones per animal. That is, each animal had a right- and a left-side upper hind leg bone (femur), and so on. If three upper left front leg bones (humeri) were found, we would know that parts of three animals had been brought into the cave. Conversely, the absence of certain bones, such as the lower rear leg, suggests that part of the animal was left at the kill site. These calculations indicate that at least 403 major food source mammals were consumed during the Solutrean occupations. Altuna also estimated in which month the younger animals died, from the eruption and wear patterns of their teeth. This tells us what time of year and for how long the cave might have been occupied.

Levels 2–3 were deposited during a cool, humid phase of the LGM. The faunal sample indicates that horses provided 56 percent of the available meat and bison 27 percent. Red deer and ibex provided 10 and 6 percent, respectively, supplemented by a single small chamois. The bones in the assemblage generally corresponded to the body parts that yield the largest amount of meat. This indicates that larger animals, such as the bison, were butchered in the field, where their less useful parts were left. By contrast, the presence of entire carcasses of smaller animals implies they were brought back to the cave for butchering.

Nearly a third of the horse and bison remains recovered at the site were encountered in the two earliest of the sixteen Solutrean levels. Although horses and bison are present in some of the later levels, only in level 7 do they approach the earlier frequency. The decline of these animals, which had the greatest payoff in terms of meat yield, may reflect overkill by the earliest Solutrean hunters or a shift in the habitat of these animals, or both.

Dental eruption and wear suggest to Altuna that the animals were killed from the end of winter or beginning of spring into the summer. He also found that 33 percent of the horses were juveniles, 43 percent were of prime age, and only 22 percent were old individuals. These percentages are a nearly perfect match for the age structure of a living population, suggesting that the animals were killed as they were randomly encountered rather than as selected targets.

Considering the constricted dimensions of La Riera Cave, we suggest that more than fourteen people would have pushed its livability and thus that it was likely occupied by an extended family. We estimate that the occupants of levels 2–3 consumed a minimum of 6,424 pounds of meat in total (table 8.1).5 This amounts to 2,443 person eating days, which could support a group of fourteen people for approximately six months.6 That length of time matches the duration of the occupations of these levels as indicated by the seasonal distribution of the animals killed. If this was a continuous occupation, by the end of those six months accessible firewood would have been exhausted, the general area would have been soiled, and local game would have been scarce. The people probably moved to an area where horses and bison were still available, along with a fresh supply of fuel.

The next use of the cave (levels 4–6) took place during a cool and dry period, when hunters set up temporary camps there to process their game. During this time the remains of whole animals were brought for processing, the less economically important portions were discarded in the cave, and those parts bearing the majority of the meat were transported to another location for consumption.

Several more features of levels 4–6 set them apart from the other Solutrean occupations of the cave: all of the indented base point fragments found in situ came from these levels; all of the Solutrean artifacts made from stone imported from outside the valley are from these levels; the occupants of levels 4–5 brought up extraordinary amounts of mollusk from the coast; two-thirds of the anadromous fish remains come from these levels; the only seal bones are from these levels; both of the self-barbed spear points or pikes at the site came from level 4 (for an example, see figure 5.4c);7 these levels’ hunters selected prime-age animals; there is no evidence that the cave was used in the late spring or summer seasons; and the thinness of the occupation lenses (accumulated debris from human habitation) and presence of simple surface fire hearths rather than large rock-lined cooking features. All of these details imply that these levels were temporary camps used by hunters based in a residential camp elsewhere in the region.

Since the faunal data support the idea that these levels were not primary habitation locations and because these levels show a marked increase in food remains obtained from estuarine and riverine environments, we propose that the hunters who occupied the cave during this period came from base camps located near the coast, some 10 kilometers downstream. The faunal analyst Jesús Ortea suggests that women and children traveled to the coast to gather shellfish during their daily foraging rounds while the men were off hunting ibex.8 That may well have been the case, but unless there was an estuary extending up a river, such a foraging expedition would have amounted to a linear round trip of at least 20 kilometers, which is 4 more than the average daily round-trip distances calculated by Louis Binford for present-day women foragers.9 Why would women travel so far for food when fresh ibex meat was probably entering the camp? Why would they bother to bring home a heavy load of mollusk in the first place, which require more energy to obtain and transport than would be gained by their consumption?

TABLE 8.1. Faunal Remains from the Solutrean Levels of La Riera Cave

If, on the other hand, these people were operating out of a base camp 10 kilometers away from La Riera, near an estuary or on the beach, the distance to the cave falls within the range calculated by Binford for daily foraging trips by male hunters. At an average speed of 2.5 kilometers per hour, a trip to the cave and back would have taken roughly 4 hours each way, allowing little time for hunting, stalking, killing, field dressing any animals killed that day, and returning home. Hence, the cave might have been used for overnight stays or more likely for several days depending on hunting success and weather conditions. Unless the trip included fishing or other animal-killing activities, it would have been necessary to bring trail food—for instance, mollusks. After a successful hunt higher in the mountains the next day, the hunters could have brought their game to the cave for secondary processing, which involved cutting up the desired parts into transportable packages.

Why use mollusks as trail food? The marine limpet Patella vulgata accounts for more than 98 percent of the mollusks in the Solutrean occupation of the cave. This species can survive up to three or four weeks when stored at temperatures of 5–12°C if protected by a covering of damp seaweed. They could not only last at least several days on the trail but also be eaten raw. Packed away in the cave, they would also provide tiding-over food before fresh meat was obtained. The presence of seal flipper bones in level 4 is likewise suggestive: coastal Inuit peoples historically used seal flippers as a handy and nutritious trail food.

Although one is struck by the abundance of mollusk in these levels, converting this source to caloric values gives a different impression. Ortea has calculated that these specimens are relatively large in comparison to those gathered along the Asturian coast today, a difference he attributes to later systematic human exploitation. By his estimate, larger individuals from areas not heavily exploited at present have an average fresh meat weight of 11.9 grams and a dry meat weight of 3.5 grams. Applying these larger fresh meat weights to La Riera gives a minimum of 12,495 grams (27 pounds) in level 4, which would support five hunters for two days; 16,422 grams (36 pounds) in level 5, which would support six hunters for two days; 1,511 grams (4 pounds) in level 6; and 6,985 grams (15.4 pounds) in level 7. One white-tailed deer provides more calories than a metric ton of fresh shellfish meat.

The occupations in these levels probably represent brief encampments primarily for upland ibex and red deer hunting. The hunters who used them selected prime-age animals, generally targeting the largest and best nourished in the herd. Such target selection hunting strategies require a relatively accurate weapon system that employs a projectile propelled by mechanical means, such as a spear thrower or a bow and arrow. The narrow seasonal use of the cave suggests that deer and goat were hunted in the late summer and fall, when they were in prime condition, also coincident with the fall salmon runs. This repeated seasonal hunting pattern suggests that such activities focused on other habitats during the winter through early summer, such as hunting sea mammals on the coast.

The climate shifted to a warmer, more humid phase during the last eleven Solutrean occupations of the cave (levels 7–17). At this time it was used once again as a residential location, and hunting was oriented primarily toward red deer. The majority of the animal bones are from the anatomical parts that contain high-yield muscle masses, strongly indicating local meat consumption. Although some juvenile red deer and ibex were slaughtered, prime-age adults dominated the sample. Such an age profile is not likely to result from random-encounter hunting and supports Straus and Clark’s conclusion that efficient trapping techniques had been developed to capture large numbers of targeted individuals. This suggests that the Solutreans offset the effects of reduced biomass or territorial prescription by increasing their efficiency in procuring those animals still available. Such tactics would require cooperation among a number of hunters and tighter, possibly hierarchical (hunt chief, hereditary leader, etc.) social organization.

The sample size in some of these upper levels was sufficient for Altuna to assess more accurately the months during which the animals were killed, which in turn identifies the time of year and the duration of occupation of the cave. Level 7 is unique in having remains of animals killed throughout all seasons of the year. Converting the amount of meat represented by the MNI into consumption per person per day indicates that there would have been enough food for an extended family of fourteen for about a year. A group of this size would have been large enough to accomplish the tactical hunting implied by the age and sex distribution of the animals represented.

If level 7 does represent a continuous occupation that lasted for a year, there must have been an increase in fuel availability. Although the environment at this time appears to have been relatively treeless, there is an increase of roe deer in the faunal record. Since these are generally considered woodland animals, their presence may imply an increase in the amount of forest near the cave. Enhanced availability of local firewood or other fuels would have enabled a small band to occupy the cave more continuously than had been possible in earlier times.

Table 8.1 shows that the amount of time spent living in and hunting from the cave varies considerably by level. It is noteworthy that no animals were incorporated into the cave deposits, with the possible exception of levels 8–9, between mid-winter and the end of spring. This means there was no hunting here during this period and that people either hunkered down at the site or abandoned it while the winter storms raged. Frozen or dried meat from fall and early winter kills could have supported a band for a short period, masking the time actually spent in residence. We are impressed, however, by the correlation of the length-of-stay calculation and the seasonality data and therefore accept that the consumption figures tend to indicate the length of time the site was occupied. If the site’s occupiers abandoned it between mid-winter and the end of spring, they must have moved to a location where resources were more abundant, such as sea mammals on the coastal ice.

The upper Solutrean levels appear to represent two residential patterns, both of which ultimately focus on red deer as the main food source. These patterns differ in use intensity and length of occupation. If the occupations were continuous, the people living in levels 7–9 may have spent up to a year at a time in the cave, whereas in levels 10–13 the stays were much shorter, averaging around three months. In those levels where it is possible to assess the seasons of occupation, they extend from spring to early summer, and the evidence from level 16 indicates that some people also stayed for a short while in early winter.

The geographer Karl Butzer hypothesized a multistage Paleolithic settlement for this part of Spain.10 His model begins with the Middle Paleolithic Mousterian and traces a slow geographic change in settlement patterns that correlates with a steady increase in human populations and technological advancements. He proposes that the primary residences were initially located at a central place established in the north Spanish piedmont belt, near or along a major river and the piedmont-mountain ecotone, where people could have easy access to a variety of resources in multiple ecological zones: a group living in a camp at this location could exploit both the coast and the mountains. Each major river valley would have defined a core territory, but minor valleys might have been shared with groups on either side. When these areas became depleted, the band would simply move to another river drainage.

By Solutrean times the population had increased and both the marine and montane zones were being exploited. Multiple groups still had overlapping operational areas, but during the subsequent Magdalenian period there was a shift to both diversification and specialization, with more effective integration of marine and montane resources. According to Butzer this situation developed into two distinct systems, one on the coastal plain and the other along the piedmont-mountain ecotone. The splitting of valleys into these two resource areas would have been particularly adaptive as the number of competing groups increased. The coastal population would have become more dependent on marine resources, requiring higher labor input but producing fairly predictable yields, while the inland groups would have relied on game trails, especially during periods of reindeer migration. The importance of this last phase of Butzer’s model is that it would have accommodated a doubling of the human population in the area.

Straus, in a model similar to Butzer’s, views the Solutrean settlement pattern as a central-base foraging system with increasing emphasis on aquatic resources, and from La Riera he estimates an average two-hour walk to and from the coast.11

From our examination of the cave evidence, we generally concur with the original investigators that the occupations can be divided into three groups based on length of residence, types of activities, and animals targeted, but in light of these models we offer the following observations for consideration.

Levels 2–3 are the earliest Solutrean occupations of La Riera, and because of the way the cave was used they stand out as different from the levels that follow. In fact, despite the presence of several key Solutrean artifact types and evidence of a shift in the selection of raw material sources, the hunting strategy associated with these levels appears to be more like that of the earlier Aurignacian people than of the later Solutreans. We suggest that these earliest hunters foraged around and from a central base residential camp, in this case La Riera, and killed animals as they encountered them, without targeting specific species or ages. When the local resources were depleted the band moved on to occupy another area.

This settlement behavior is compatible with Straus’s interpretation and is the overlapping operational stage of Butzer’s model, in which the local band shares resource areas with neighboring groups. Our conjecture is that these undated occupations occurred early enough in the LGM that its climatic changes and the increased population had not yet impacted resources in the Vasco-Cantabrian area, where it was business as usual.

After the onset of the cold, dry period, population pressure began to reduce the size of territories and bands started establishing semi-permanent base camps in strategic locations near more reliable resource areas. Working out of their home base, these foragers used short-term occupation sites in task-specific localities and returned home with whatever goods they acquired during the trip. Levels 4–6, the specialized ibex and red deer hunting camps recognized by Clark and Straus, are clear examples of the use of La Riera as a temporary shelter for staging task-specific foraging trips. The mix of shouldered projectile points and indented base projectile points may indicate that at least two different contemporary social groups used the cave.

We suggest, on the basis of the thinness of the occupation lenses, that these levels were produced by small subsets of extended family groupings, perhaps consisting of only male hunters on two-to-three-day trips. The fish remains also suggest that many of these trips were late summer or fall excursions, when the salmon and sea trout were spawning. At the cave the hunters either consumed or filleted the fish whose remains were recovered from the occupation levels, while they perhaps dried or smoked other fish and took them back to a base camp along with selected high-yield food packages.

Because of the dramatic appearance of aquatic resources such as shellfish, fish, and seal, we propose that semi-permanent base camps for the La Riera hunters were downstream and near the beach or estuaries (figure 8.2). Campsites in sheltered localities near these environments would have had many advantages over upland campsites, including relatively continuous opportunities to obtain high-yield resources such as fish, waterfowl, and some sea mammals. Shellfish would be a great resource when found near a campsite, whereas their advantage would ebb exponentially when transported many kilometers. Another direct advantage would be the possibility of collecting driftwood that ends its long journey from southeastern North America tossed by storms onto the beaches of the Bay of Biscay.

The adjacent continental shelf was a vast plain and an excellent habitat for herd mammals that, along with the abundant coastal and marine resources, would have provided food for people living on the coast. In fact, for bison and horses this cold dry, steppe environment would have been much superior to the unstable, steep slopes and deeply incised valleys of the Cantabrian piedmont. Bones from dredging operations in the North Sea and English Channel indicate that mammoth herds and other extinct animals also grazed on the plain.12

FIGURE 8.2.

Ecological zones where the highest-return resources were available throughout the year.

If semi-permanent camps were in prominent coastal locations, they could have enhanced inter-band social contacts between areas of southern France and Iberia. Here we see the effects of two important terrain-dependent aspects, visibility and accessibility. First, people would have been much easier to find camped at prominent sites along the beach than hidden away in the broken topography and deeply incised countryside of the piedmont and mountains. Second, the continental plain would have been a virtual inter-area autobahn connecting groups from Asturias to the Aquitaine and beyond. Trails on the plain would have been far superior for travel than the seesaw trails up and down the steep and unstable slopes of the high ground and over-mountain passes that were seasonally blocked by snow and ice—although except when the plain’s rivers were frozen over, some sort of watercraft would have been desirable to manage their crossings.

In terms of Butzer’s model this period represented a transition from the early overlapping operational central place pattern to the beginnings of a regional specialization phase. Although there was probably still overlapping use of neighboring territories, extended kin networks or other alliances would have socially formalized the use of these areas. In levels 4–6 the settlement system would have included entire drainage areas, from the shoreline to the snow line. Once a base camp was established, upland hunting would continue, but on an ad hoc basis and probably highly related to seasonally specific tasks such as fall hunts, when red deer and ibex were in prime condition.

We agree that the last series of occupation levels (7–17) shows that the cave was again used primarily as a home base, but here the pattern of use was more complicated and variable than in levels 2–3. The refuse midden of level 7 is large enough to suggest a long-term encampment. It appears to be related to the previous three levels in that it maintains a strong component of both estuarine and riverine resources, as well as shared artifact types. It differs in the development of intensive red deer hunting, suggesting another change in the social, settlement, and procurement systems of the valley brought on by a climatic shift, loss of some maritime species, economic specialization, or perhaps continuing population increase.

By level 7, we think, the population had increased to the point of beginning the “fission” stage of Butzer’s model, when the semi-related group of people (a band) separates into distinct inland and coastal groups. It is clear that bands at this level were beginning to use the piedmont and lower foothills for more extended periods of time or even on a semi-permanent basis. From level 7 up, with the exception of a period between levels 10 and 13, the duration of camp activities seems to range from eight or nine months to perhaps a year.

There is, however, a period from mid-winter through spring when the cave seems to have been abandoned by all later Solutrean people—oddly enough, corresponding to prime sealing months. In 81 percent of the Solutrean occupation levels for which there are seasonal data, the caves appear to be abandoned during the time when seal hunting would have been optimum on the coast. Figure 8.3 compares the calculation of seasons of the upper Solutrean occupation of La Riera Cave with periods of seal vulnerability (the birthing schedule of seals that live on the ice edge is regulated by seasons, so that pups are weaned by the time the ice breaks up in the spring). This correlation is highly suggestive that inland groups of Solutrean hunters moved down to the coast for several months during late winter to participate in sealing and probably provided the coastal people with mountain products such as ibex, chamois, and roe deer meat and durable goods. For the coastal group, most seal hunting could have taken place anytime there was sea ice in the neighborhood, either landfast or floating. Plus, the harbor seal was a year-round coastal resident and could be hunted during the summer, when sea ice was absent.

FIGURE 8.3.

Seasonal chart of seal and walrus presence on the northern Spanish coasts and La Riera Cave use in Solutrean times.

Perhaps we are seeing evidence of a settlement pattern similar to that of the Inuit of northwest Alaska. There the coastal and inland populations generally operate independently, but during certain seasons of the year the inland groups go to the beach for trading, hunting, and other social activities with their coastal relatives (a periodic regional aggregation group, in Binford’s terminology). We contend that this would have been part of a natural progression leading to Butzer’s adaptive divergence stage.

Both Butzer and Straus make passing mention of a possible Solutrean coastal adaptation, but they do not seriously consider it while model building because there is no proof. Based on the hard data available, it would indeed appear that economic intensification and integration of marine and montane resources began during the Magdalenian, but we think this reflects archaeological invisibility caused by the post-LGM sea level rise rather than a difference in cultural development.

This point is illustrated by Darrin Lowery’s work on Late Woodland occupation in the watershed of Chesapeake Bay in North America.13 The eastern shore of the bay includes large estuarine sites with dense shellfish refuse and ample evidence of the use of other marine resources, as well as interior hunting-oriented sites with limited debris. The interior sites are generally located near freshwater springs that had been attractive to hunter-gatherers since Paleolithic people settled in the area. If global warming were to cause today’s sea level to rise 2 meters, the Late Woodland sites with marine refuse middens would disappear and there would be no archaeological record of the use of marine resources. The settings of the surviving terrestrial Late Woodland sites would mimic the settings of the European Paleolithic sites and provide fewer clues than exist at La Riera to indicate that the Late Woodland peoples gained most of their resources from the bay and ocean. Similar situations exist in many other places in the world where sea level rise or coastal subsidence has wiped out entire components of prehistoric settlement systems.

We assume that, like the Late Woodland fishing folks, most prehistoric people operating out of semi-permanent base camps did not carry marine hunting and fishing equipment with them while exploiting upland terrestrial environments unless it was multi-functional, such as spear throwers and darts, which are effective on both open land and water. Bows and arrows and self-barbed lances are also effective in a variety of hunting and fishing environments. Boats and toggling harpoons, on the other hand, would have been left behind.

We would not normally expect to see marine food items carried any great distance from the coastline. In an excellent summary article of the issues involved with archaeological evidence for aquatic adaptations, Jon Erlandson points out that when modern hunters-gatherers forage beyond their base camp for 5–10 kilometers, they do not usually transport the skeletal remains of shellfish, fish, or sea mammals back to their residential camp.14 Therefore, sites located more than about 5–10 kilometers from an ancient shoreline are not likely to contain substantial evidence of marine resource use, and even in sites as close as 1 or 2 kilometers from shore the density of aquatic remains drops significantly. The exceptions to this are marine mammal ivory and teeth that were used for adornment. These specimens can be transported great distances from the coast and were traded to remote interior peoples. Levels 4–6 at La Riera Cave contained a remarkable amount of estuarine and marine remains considering the cave’s location in an upland setting and its distance from the coast.

Clark and Straus illustrate resource intensification beginning in Solutrean times with the development of technical innovations to increase hunting efficiency.15 Among the new technologies they consider are decoys, nets, movable fences, and weapons such as spear throwers and possibly bows and arrows. All of these hunting aids would have been made of perishable materials (e.g., wood, plant fiber, animal tissue), which are usually not preserved in archaeological contexts. Except for evidence such as spear thrower parts recovered in excavations and their depictions in rock art, the use of these new hunting technologies by Solutrean people remains in the domain of speculation. But since the number of new artifact types found in Solutrean sites is relatively extensive, it is clear that these people were heavily invested in research and development (see chapter 5). It seems probable, therefore, that they developed and used not only these hunting aids but also myriad other tools and exploitive and protective systems for which there is no direct evidence. This would be especially true of equipment for the exploitation of marine resources, which was likely stored at campsites near beaches long ago destroyed by sea transgression.

All of the available evidence suggests that European Paleolithic armaments prior to Solutrean times consisted primarily of thrusting and casting weapons. A wide variety of new projectile point types and several new weapon systems first appear during the Solutrean and are suspected by Clark and Straus to be the result of experimental efforts to develop more efficient means of killing game as a response to population increase. Although this may have been true, we think the situation was more complicated and that several issues directly related to climate change should be equally considered as part of the impetus for the development of new hunting gear and techniques. Perhaps the diverse varieties of the projectile point types seen during Solutrean times were experimental prototypes, many of which were abandoned through time.

The Solutrean people were among the first modern humans to face a glacial period in Europe, and climatic change, especially associated with deforestation, would have had a direct impact on their hunting techniques and available raw materials. The loss of forests and redistribution of animals would have greatly diminished the opportunities for ambush hunting such as seen in levels 2–3 of La Riera Cave. Instead of a multitude of places along game trails in the woods, there would have been fewer locations where hunters could hide. Game stalking would have become a fine art as opportunities to get close to targets were greatly reduced. This would have been especially true on the vast plain of the continental shelf, which became a mecca for ungulates. An additional stress resulting from the loss of the forest environment would have been the dramatic decrease of wood for tools, especially long straight spear shafts, and for fuel. It is probable that driftwood cast up on the ice age shores augmented the supply of wood from the rare and scrubby native trees.

Developing accurate long-range shooting equipment for hunting in an open steppe environment would have been necessary, in addition to learning completely new sets of hunting skills. The formation of large, organized groups of hunters for animal trapping and manipulation would have provided an advantageous edge for survival during these times. All of these innovations, necessary to efficiently exploit the newly emerging open steppe, would have been equally adaptable to hunting ice edge environments.

The simple sharp-pointed thrusting spears used by humans throughout the majority of our time on earth were improved. New weapons had multiple parts, including fore-shafts, with socketed projectiles to which end or side blades were attached. The least complicated of these innovations were thrusting spears with a projectile point made of flaked stone, bone, antler, or ivory.

More complex systems were developed with shaft modifications that accommodated new propulsion methods suited to the new hunting situations. These included darts cast with throwing boards and arrows shot by bows. The latter are conjectured based on the size of single-shouldered points and on small-stemmed projectile points found primarily in southern Spain and Portugal. The simple thrusting spear was further improved by the attachment of a self-barbed spear point (see figure 5.4a).

All of these systems have different and multiple hafting arrangements, including rigidly mounted points and detachable, interchangeable, and replaceable parts (figure 7.5). Multiple components can include a blade set into a harpoon-like socket, the latter either firmly fixed to the foreshaft or designed to break apart from it on impact. Likewise foreshafts and shafts could be firmly fixed together or designed to break apart on impact. All of these systems might or might not have had cords or lines attached to either the blade socket or the foreshaft. The advantage of the line is that it allows the hunter to hold onto the shaft or attach the weapon tip to a weight or float. When an unfortunate beast reaches the end of the cord, either it is held fast or the weapon tip is torn from its body, causing an ugly, lethal wound. Attachment accommodations are most important for aquatic hunting, since they provide for the retrieval of dead or wounded animals before they sink beneath the water. It is thought that line holes drilled through Magdalenian harpoon heads represent the beginning of aquatic harpoon technology.16 However, lines were not that necessary during the LGM, since the elevated salt content of the seawater kept mortally wounded animals from sinking rapidly. Retrieval could have been accomplished in many ways, including boating out, casting a grappling hook and line, or simply waiting for the animal to drift ashore.

Perhaps as important to Solutrean hunters as the efficiency of the new weapons was the fact that these break-apart systems allowed for the retrieval and long-term survivability of spear shafts. Because of the deforestation of the Spanish countryside during the LGM, long pieces of wood suitable for spear shafts were likely rare. Even before then, from searching for suitable pieces of wood to shaping and straightening, shaft construction was a major time-consuming process. The development of detachable foreshafts likely saved many a spear shaft from ruin and allowed the hunter to retrieve the shaft. This was a particular novelty in aquatic environments. Such systems also allowed hunters to re-arm with a new weapon tip and take additional shots at other targets. Consequently, we agree with Straus that Solutrean hunters used foreshafts, and we propose that some of the bone and antler rods with blunted or rounded distal ends were probably used as foreshafts rather than projectile points.17

A relatively wide variety of stone and bone artifacts found in Solutrean sites have been identified as projectile points. These include unifacial and bifacially flaked stone points of various shapes, such as laurel leaf, willow leaf, shouldered, concave base, and tanged, as well as several kinds of bone and antler points with hafting arrangements and modifications for the insertion of stone side blades. Some of these point types may be associated in the same occupation levels in various sites, but the variety of point types and number of forms vary in different areas and throughout time. Thus, Solutrean occupations can be distinguished by having some point types and not others. Part of this variation is probably temporal, but some of it may be ethnic, with overlap resulting from contact between regional bands or from population movements. It is also possible that different point types correspond to weapons used for hunting specific types of game.18

The self-barbed spear point and the indented base point first appear at La Riera in level 4, the beginning of the second phase of the Solutrean occupations. Self-barbed spear points are slightly curved bipointed bone or antler rods that are flattened and scored on the curve’s outside surface so they can be hafted to a spear shaft with both ends of the point exposed (figure 5.4a). The leading point is for penetration, and the trailing point acts as a barb to attach the weapon securely to the prey so it can’t drift away or sink. The presence of self-barbed points and fish remains in Solutrean levels, combined with the fact that similar weapons are still used by various groups for fish spearing, makes an excellent case for Solutrean people’s using these artifacts in the same activities. This type of spear would have been equally effective for hunting seals at breathing holes and serves the same function as a metal sealing pike.

Straus has suggested that indented base projectile points (figure 5.10) and end blades were used on regular thrusting spears, while small single-shouldered points were used on the slender shafts of darts cast by spear throwers or on arrows (figure 5.6c).19 In a sample of 100 shoulder points, he found an average maximum width of 1.37 centimeters with a standard deviation of 0.30 centimeters, while 45 concave base points had an average width of 2.29 centimeters and a standard deviation of 0.42 centimeters. These differences in width support the notion that the two types of points were indeed hafted differently.

To examine this idea, we compared Straus’s measurements to those calculated for triangular stone points from Late Prehistoric sites along the California and Oregon coasts. At these North American sites, arrows and harpoons were used to hunt terrestrial and aquatic mammals, respectively. In a study of West Coast projectile points, Lee Lyman, Linda Clark, and Richard Ross found that arrow points with small concave bases have an average width of 1.42 centimeters with a standard deviation of 0.22 centimeters.20 Larger concave to straight base points—which were used as tips for bone or antler harpoons when hunting sea mammals, according to native informants—averaged 2.95 centimeters with a standard deviation of 0.33 centimeters. These figures compare favorably to both Solutrean point styles in Straus’s theory, supporting his idea that the narrow-shouldered points were used on arrows or narrow dart shafts and the broader concave base points on heavier spears. (Such heavier spears may well have been tipped with harpoon-like sockets armed with end blades.) The theory is further supported by the coastal distribution of Solutrean concave base points (figure 8.1).

In summary, it appears that most of the new weapon systems developed during Solutrean times were ideally suited for open steppe and aquatic hunting. Among the innovations for which there is tangible evidence are spear foreshafts and harpoon-like end blades; both strongly imply that Solutrean hunters used detachable end blade sockets, which are found in most if not all primitive marine mammal hunting tool kits. Further, the self-barbed spear is an unquestionably aquatic hunting adaptation that historic northern Europeans used for hunting seals at breathing holes. Although the presence of these weapons does not prove that Solutrean peoples hunted marine mammals, it does mean that they had developed the equipment to do so, and there is no reason to suspect that they would not have thought it a good idea—especially while visiting the coast during the prime seal-hunting months.

Inasmuch as the evidence suggests that Solutrean culture existed for some 3,500 or more years and that during most if not all of this time a major part of their settlement system was directly adjacent to or at least in view of the ice age sea, we consider it entirely unlikely that these acknowledged great innovators would not have learned to understand and exploit this environment. In fact, it is possible that many of the innovations with which they are credited were the direct result of a maritime adaptation.