As a young Dutch engineer, Geert once applied for a junior management job with an American engineering company that had recently settled in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium. He felt well qualified, with a degree from the leading technical university of the country, good grades, a record of active participation in student associations, and three years’ experience as an engineer with a well-known (although somewhat sleepy) Dutch company. He had written a short letter to the company indicating his interest and providing some salient personal data. He was invited for an interview, and after a long train ride he sat facing the American plant manager. Geert behaved politely and modestly, as he knew an applicant should, and waited for the other man to ask the usual questions that would enable him to find out how qualified Geert was. To his surprise, the plant manager touched on very few of the areas that Geert thought should be discussed. Instead, he asked about some highly detailed facts pertaining to Geert’s experience in tool design, using English words that Geert did not know, and the relevance of the questioning escaped him. Those were things he could learn within a week once he worked there. After half an hour of painful misunderstandings, the interviewer said, “Sorry—we need a first-class man.” And Geert was out on the street.

Years later Geert was the interviewer, and he met with both Dutch and American applicants. Then he understood what had gone wrong in that earlier case. American applicants, to Dutch eyes, oversell themselves. Their curricula vitae are worded in superlatives, mentioning every degree, grade, award, and membership to demonstrate their outstanding qualities. During the interview they try to behave assertively, promising things they are very unlikely to realize—such as learning the local language in a few months.

Dutch applicants, in American eyes, undersell themselves. They write modest and usually short CVs, counting on the interviewer to find out how good they really are by asking. They expect an interest in their social and extracurricular activities during their studies. They are careful not to be seen as braggarts and not to make promises they are not absolutely sure they can fulfill.

American interviewers know how to interpret American CVs and interviews, and they tend to discount the information provided. Dutch interviewers, accustomed to Dutch applicants, tend to upgrade the information. The scenario for cross-cultural misunderstanding is clear. To an uninitiated American interviewer, an uninitiated Dutch applicant comes across as a sucker. To an uninitiated Dutch interviewer, an uninitiated American applicant comes across as a braggart.

Dutch and American societies are reasonably similar on the dimensions of power distance and individualism as described in the two previous chapters, but they differ considerably on a third dimension, which opposes, among other things, the desirability of assertive behavior against the desirability of modest behavior. We will label it masculinity versus femininity.

All human societies consist of men and women, usually in approximately equal numbers. They are biologically distinct, and their respective roles in biological procreation are absolute. Other physical differences between women and men, not directly related to the bearing and begetting of children, are not absolute but statistical. Men are on average taller and stronger, but many women are taller and stronger than quite a few men. Women have on average greater finger dexterity and, for example, faster metabolism, which enables them to recover faster from fatigue, but some men excel in these respects.

The absolute and statistical biological differences between men and women are the same the world over, but the social roles of men and women in society are only partly determined by the biological constraints. Every society recognizes many behaviors, not immediately related to procreation, as more suitable to females or more suitable to males, but which behaviors belong to either gender differs from one society to another. Anthropologists having studied nonliterate, relatively isolated societies stress the wide variety of social sex roles that seem to be possible.1 For the biological distinction, this chapter will use the terms male and female; for the social, culturally determined roles, the terms are masculine and feminine. The latter terms are relative, not absolute: a man can behave in a “feminine” way and a woman in a “masculine” way; this means only that they deviate from certain conventions in their society.

Which behaviors are considered feminine or masculine differs not only among traditional societies but also among modern societies. This is most evident in the distribution of men and women over certain professions. Women dominate as doctors in Russia, as dentists in Belgium, and as shopkeepers in parts of West Africa. Men dominate as typists in Pakistan and form a sizable share of nurses in the Netherlands. Female managers are virtually nonexistent in Japan but frequent in the Philippines and Thailand.

In spite of the variety found, there is a common trend among most societies, both traditional and modern, as to the distribution of social sex roles. From now on, this chapter will use the more politically correct term gender roles. Men are supposed to be more concerned with achievements outside the home—hunting and fighting in traditional societies, the same but translated into economic terms in modern societies. Men, in short, are supposed to be assertive, competitive, and tough. Women are supposed to be more concerned with taking care of the home, of the children, and of people in general—to take the tender roles. It is not difficult to see how this role pattern is likely to have developed: women first bore the children and then usually breast-fed them, so at least during this period they had to stay close to the children. Men were freer to move around, to the extent that they were not needed to protect women and children against attacks by other men and by animals.

Male achievement reinforces masculine assertiveness and competition; female care reinforces feminine nurturance and a concern for relationships and for the living environment.2 Men, taller and stronger and free to get out, tend to dominate in social life outside the home; inside the home a variety of role distributions between the genders is possible. The role pattern demonstrated by the father and mother (and possibly other family members) has a profound impact on the mental software of the small child who is programmed with it for life. Therefore, it is not surprising that one of the dimensions of national value systems is related to gender role models offered by parents.

The gender role socialization that started in the family continues in peer groups and in schools. A society’s gender role pattern is daily reflected in its media, including TV programs, motion pictures, children’s books, newspapers, and women’s journals. Gender role–confirming behavior is a criterion for mental health.3 Gender roles are part and parcel of every society.

Chapter 4 referred to a set of fourteen work goals in the IBM questionnaire: “Try to think of those factors that would be important to you in an ideal job; disregard the extent to which they are contained in your present job.” The analysis of the answers to the fourteen work goal items produced two underlying dimensions. One was individualism versus collectivism: the importance of personal time, freedom, and challenge stood for individualism, while the importance of training, physical conditions, and use of skills stood for collectivism.

The second dimension came to be labeled masculinity versus femininity. It was associated most strongly with the importance attached to the following work goal items:

For the masculine pole

1. Earnings: have an opportunity for high earnings

2. Recognition: get the recognition you deserve when you do a good job

3. Advancement: have an opportunity for advancement to higher-level jobs

4. Challenge: have challenging work to do—work from which you can get a personal sense of accomplishment

For the opposite, feminine pole

5. Manager: have a good working relationship with your direct superior

6. Cooperation: work with people who cooperate well with one another

7. Living area: live in an area desirable to you and your family

8. Employment security: have the security that you will be able to work for your company as long as you want to

Note that the work goal challenge was also associated with the individualism dimension (Chapter 4). The other seven goals are associated only with masculinity or femininity.

The decisive reason for labeling the second work goals dimension masculinity versus femininity is that this dimension is the only one on which the men and the women among the IBM employees scored consistently differently (except, as will be shown, in countries at the extreme feminine pole). Neither power distance nor individualism nor uncertainty avoidance showed a systematic difference in answers between men and women. Only the present dimension produced such a gender difference, with men attaching greater importance to, in particular, work goals 1 and 3 and women to goals 5 and 6. The importance of earnings and advancement corresponds to the masculine, assertive, and competitive social role. The importance of relations with the manager and with colleagues corresponds to the caring and social-environment-oriented feminine role.

As in the case of the individualism versus collectivism dimension, the eight items from the IBM questionnaire do not cover all there is to the distinction between a masculine and a feminine culture in society. They just represent the aspects of this dimension that were represented by questions in the IBM research. Again the correlations of the IBM country scores with non-IBM data about other characteristics of societies allow for a full grasp of what the dimension encompasses.

The differences in mental programming among societies related to this new dimension are social but are even more emotional. Social roles can be imposed by external factors, but what people feel while playing them comes from the inside. This state of affairs leads us to the following definition:

A society is called masculine when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.

A society is called feminine when emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.

For the countries in the IBM database, masculinity index (MAS) values were calculated in a way similar to individualism index values (Chapter 4). MAS was based on the country’s factor score in a factor analysis of the fourteen work goals. Scores were put into a range from about 0 for the most feminine country to about 100 for the most masculine country through multiplying the factor scores by 20 and adding 50. For follow-up studies, an approximation formula was used in which MAS was directly computed from the mean scores of four work goals.

Country MAS scores are shown in Table 5.1. As with the scores for power distance and individualism, the masculinity scores represent relative, not absolute, positions of countries. Unlike with individualism, masculinity is unrelated to a country’s degree of economic development: we find rich and poor masculine and rich and poor feminine countries.

The most feminine-scoring countries (ranks 76 through 72) were Sweden, Norway, Latvia, the Netherlands, and Denmark; Finland came close with a rank of 68. The lower third of Table 5.1 further contains some Latin countries: Costa Rica, Chile, Portugal, Guatemala, Uruguay, El Salvador, Peru, Spain, and France; and some Eastern European countries: Slovenia, Lithuania, Estonia, Russia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Serbia. From Asia it contains Thailand, South Korea, Vietnam, and Iran. Other feminine-scoring cultures were the former Dutch colony of Suriname in South America, the Flemish (Dutch-speaking Belgians), and countries from the East African region.

TABLE 5.1 Masculinity Index (MAS) Values for 76 Countries and Regions Based on Factor Scores from 14 Items in the IBM Database Plus Extensions

The top third of Table 5.1 includes all Anglo countries: Ireland, Jamaica, Great Britain, South Africa, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Trinidad. Also from Europe are Slovakia (with a rank of 1), Hungary, Austria, German-speaking Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Poland, and the French-speaking Belgians and Swiss. In Asia are Japan (rank 2), China, and the Philippines. From Latin America are the larger countries around the Caribbean—Venezuela, Mexico, and Colombia—and Ecuador.

The United States scored 62 on MAS (rank 19) and the Netherlands 14 (rank 73), so these two countries figuring in the story at the beginning of this chapter were markedly far apart.

Masculinity-femininity has been the most controversial of the five dimensions of national cultures. This is a matter not only of labeling (users are free to adapt the labels to their taste—for instance, performance-oriented versus cooperation-oriented) but also of recognizing that national cultures do differ dramatically on the value issues related to this dimension. At the same time, ever since Geert’s first publication on the subject in the 1970s, the number and scope of validations of the dimension have continued to grow. Several of these validations have been bundled in a 1998 book, Masculinity and Femininity: The Taboo Dimension of National Cultures.4 Of note is that the dimension is politically incorrect mainly in masculine cultures such as the United States and the UK, but not in feminine cultures such as Sweden and the Netherlands. Taboos are strong manifestations of cultural values.

One reason the masculinity-femininity dimension is not recognized is that it is entirely unrelated to national wealth. For the other three IBM dimensions, wealthy countries are more often found on one of the poles (small power distance, individualist, and somewhat weaker uncertainty avoidance), and poor countries on the other. The association with wealth serves as an implicit justification that one pole must be better than the other. For masculinity-femininity, though, this does not work. There are just as many poor as there are wealthy masculine, or feminine, countries. So, wealth is no clue on which to base one’s values, and this fact unsettles people. In several research projects, the influence of MAS became evident only after the influence of wealth had been controlled for.

From the six major replications of the IBM surveys described earlier in Table 2.1, five found a dimension similar to masculinity-femininity. The sixth, Shane’s study among employees of six other international companies, excluded the questions related to MAS because the dimension was considered offensive. What is not asked cannot be found. In Søndergaard’s review of nineteen smaller replications, also mentioned in Chapter 2, fourteen confirmed the MAS differences. This in itself is a statistically significant result.5

Schwartz’s value study among elementary school teachers produced a country-level mastery dimension that correlated significantly with MAS.6 Mastery combines the values ambitious, capable, choosing own goals, daring, independent, and successful, all on the positive pole. These values clearly confirm a masculine ethos.7

Robert House, when designing the GLOBE study, meant to replicate the Hofstede study, but he did not go as far as using the taboo terms masculinity and femininity. Instead, GLOBE included four other dimensions with potential conceptual links to Geert’s masculinity versus femininity dimension: assertiveness, gender egalitarianism, humane orientation, and performance orientation. Across forty-eight common countries, the only GLOBE dimension significantly correlated with MAS was assertiveness “as is,” but we came closer to our MAS dimension with a combination of assertiveness “as is” and assertiveness “should be.”8 GLOBE did tap the assertiveness aspect of our MAS dimension, although in a diluted form.

From the other potentially associated GLOBE dimensions, gender egalitarianism, both “as is” and “should be,” correlated not with MAS but with our IDV. In Chapter 4 some aspects of gender equality in society (men make better leaders; women should be chaste, but men don’t need to be) were shown to relate to collectivism. Gender equality has a lot to do with women’s education level, which relates strongly to national wealth and therefore indirectly to individualism. The relationships of women’s and men’s roles to the MAS dimension, as this chapter will show, are more on the emotional level.

Performance orientation “as is” correlated negatively with our uncertainty avoidance (UAI, see Chapter 6), and performance orientation “should be” correlated negatively with long-term orientation (LTO, see Chapter 7). Humane orientation “as is” and “should be” produced no significant correlations. We doubt whether this GLOBE dimension makes any sense at all.9

In the literature the distinction between country-level masculinity and femininity is easily confused with the distinction between individualism and collectivism. Authors from the United States tend to classify feminine goals as collectivist, whereas a student from Korea in her master’s thesis classified masculine goals as collectivist.

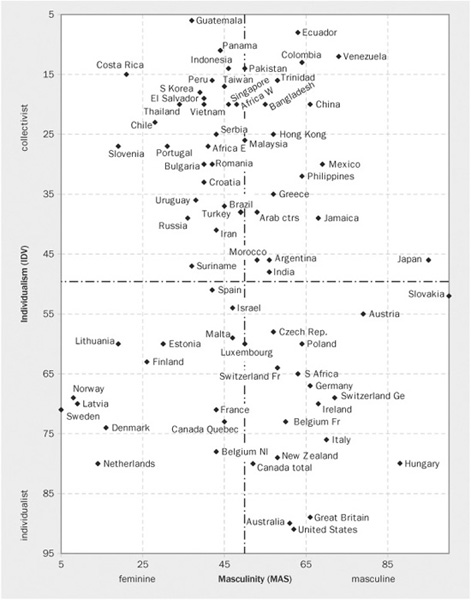

In reality the individualism-collectivism and masculinity-femininity dimensions are independent, as is evident in Figure 5.1, in which the two dimensions are crossed. All combinations occur with about equal frequency. The difference between them is that individualism-collectivism is about “I” versus “we,” independence from in-groups versus dependence on in-groups. Masculinity-femininity is about a stress on ego versus a stress on relationship with others, regardless of group ties. Relationships in collectivist cultures are basically predetermined by group ties: “groupiness” is collectivist, not feminine. The biblical story of the Good Samaritan who helps a Jew in need—someone from another ethnic group—is an illustration of feminine and not of collectivist values.

As we mentioned in Chapter 4, Inglehart’s overall analysis of the World Values Survey found a key dimension, well-being versus survival, that was associated with the combination of high IDV and low MAS.10 This means that the highest stress on well-being occurred in individualist, feminine societies (such as Denmark), while the highest stress on survival was found in collectivist, masculine societies (such as Mexico). We will meet this dimension from Inglehart again in Chapter 8, relating it to Misho’s new dimension indulgence versus restraint.

As in the case of individualism and collectivism, the objection is sometimes made that masculinity and femininity should be seen as two separate dimensions. Again the answer to the question of whether we’re talking about one dimension or two is that it depends on our level of analysis. It depends on whether we try to compare the cultures of entire societies (which is what this book is about) or to compare individuals within societies. An individual can be both masculine and feminine at the same time,11 but a country culture is either predominantly one or predominantly the other. If in a country more people hold masculine values, fewer people hold feminine values.

FIGURE 5.1 Masculinity Versus Individualism

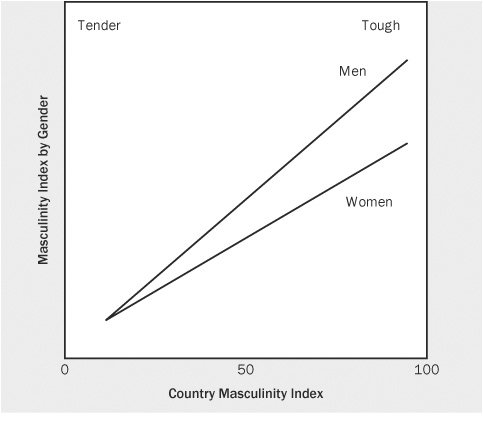

Country MAS scores were also computed separately for men and women.12 Figure 5.2 shows in simplified form the relationship between masculinity by gender and masculinity by country. It reveals that from the most feminine (tender) countries to the most masculine (tough) countries, both the values of men and of women became tougher, but the country difference was larger for men than for women. In the most feminine countries, Sweden and Norway, there was no difference between the scores of men and women, and both expressed equally tender, nurturing values. In the most masculine countries in the IBM database, Japan and Austria, the men scored very tough and the women fairly tough, but the gender gap was largest. From the most feminine to the most masculine country, the range of MAS scores for men was about 50 percent wider than the range for women. Women’s values differ less among countries than men’s values do, and a country’s femininity is more clearly reflected in the values of its men than in those of its women. Women across countries can be expected to agree more easily on issues in which ego values are at stake. A U.S. bestseller was called Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus, but in feminine cultures both sexes are from Venus.13

FIGURE 5.2 Country Masculinity Scores by Gender

Richard Lynn, from Northern Ireland, collected data about attitudes toward competitiveness and money from male and female university students in forty-two countries. Overall, men scored higher on competitiveness than women. In a reanalysis, Evert van de Vliert, from the Netherlands, showed that the ratio between men’s and women’s scores was significantly correlated with MAS. It was lowest in Norway, where the women rated their competitiveness higher than the men, and was highest in Germany.14

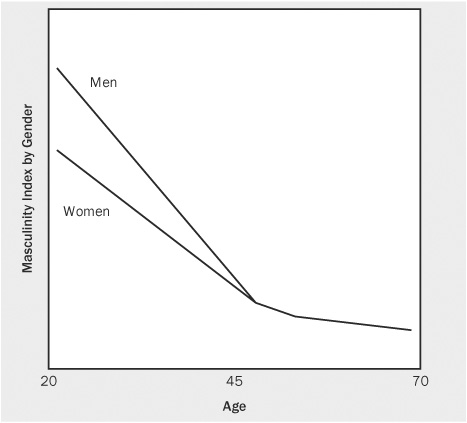

Figure 5.3 shows schematically the age effects on masculinity values.15 When people grow older, they tend to become more social and less ego oriented (lower MAS). At the same time, the gap between women’s and men’s MAS values becomes smaller, and at around age forty-five it has closed completely. This is the age at which a woman’s role as a potential child-bearer has generally ended; there is no more biological reason for her values to differ from a man’s (except that men can still beget).

FIGURE 5.3 MAS Scores by Gender and Age

This development fits the observation that young men and women foster more technical interests (which could be considered masculine), and older men and women foster more social interests. In terms of values (but not necessarily in terms of energy and vitality), older persons are more suitable as people managers and younger persons as technical managers.

In the IBM research, occupations could (on the basis of the values of those who were engaged in them) be ordered along a tough-tender dimension. It did make sense to call some occupations more masculine and others more feminine. It was no surprise that the masculine occupations were mostly filled by men, and the feminine occupations mostly by women. However, the differences in values were not caused by the gender of the occupants. Men in feminine occupations held more feminine values than women in masculine occupations.

The ordering of occupations in IBM from most masculine to most feminine was as follows:

1. Sales representatives

2. Engineers and scientists

3. Technicians and skilled craftspeople

4. Managers of all categories

5. Semiskilled and unskilled workers

6. Office workers

Sales representatives were paid on commission, in a strongly competitive climate. Scientists, engineers, technicians, and skilled workers focused mostly on technical performance. Managers dealt with both technical and human problems, in roles with both assertive and nurturing elements. Unskilled and semiskilled workers had no strong achievements to boast of but usually worked in cooperative teams. Office workers also were less oriented toward achievements and more toward human contacts with insiders and outsiders.

As only a small part of gender role differentiation is biologically determined, the stability of gender role patterns is almost entirely a matter of socialization. Socialization means that both girls and boys learn their place in society, and once they have learned it, the majority of them want it that way. In male-dominated societies, most women want the male dominance.

The family is the place where most people received their first socialization. The family contains two unequal but complementary role pairs: parent-child and husband-wife. The effects of different degrees of inequality in the parent-child relationship were related to the dimension of power distance in Chapter 3. The prevailing role distribution between husband and wife is reflected in a society’s position on the masculinity-femininity scale.

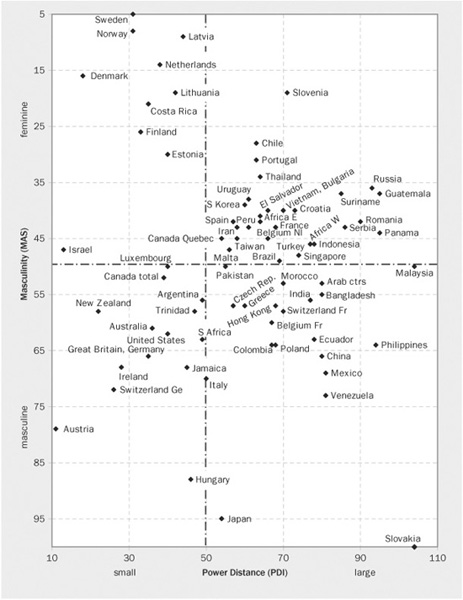

Figure 5.4 crosses PDI against MAS. In the right half of the diagram (where PDI values are high), inequality between parents and children is a societal norm. Children are supposed to be controlled by obedience. In the left half, children are controlled by the examples set by parents. In the lower half of the diagram (where MAS scores are high), inequality between fathers’ and mothers’ roles (father tough, mother less tough) is a societal norm. Men are supposed to deal with facts, women with feelings. In the upper half, both men and women are allowed to deal with the facts and with the soft things in life.

Thus, the lower right-hand quadrant (unequal and tough) stands for a norm of a dominant, tough father and a submissive mother who, although also fairly tough, is at the same time the refuge for consolation and tender feelings. This quadrant includes the Latin American countries in which men are supposed to be macho. The complement of machismo for men is marianismo (being like the Virgin Mary) or hembrismo (from hembra, a female animal) for women: a combination of near-saintliness, submissiveness, and sexual frigidity.16

The upper right-hand quadrant (unequal and tender) represents a societal norm of two dominant parents, sharing the same concern for the quality of life and for relationships, both providing at times authority and tenderness.

In the countries in the lower left-hand quadrant (equal and tough), the norm is for nondominant parents to set an example in which the father is tough and deals with facts and the mother is somewhat less tough and deals with feelings. The resulting role model is that boys should assert themselves and girls should please and be pleased. Boys don’t cry and should fight back when attacked; girls may cry and don’t fight.

FIGURE 5.4 Power Distance Versus Masculinity

Finally, in the upper left-hand quadrant (equal and tender), the norm is for mothers and fathers not to dominate and for them both to be concerned with relationships, with the quality of life, with facts, and with feelings, setting an example of a relative equality of gender roles in the family context.

In Chapter 4 we referred to a 2005 market research study regarding ideals of beauty and body image among fifteen- to seventeen-year-old girls from ten countries around the world. As the source of the most powerful influence on their beauty ideals, girls in feminine cultures more often mentioned their father and their mother. In the case of the mother’s influence, (higher) power distance also played a role. In masculine cultures, girls most often referred to the media and to celebrities.17

In Chapter 3 we referred to Eurobarometer data about full-time and part-time work between sets of parents. Whether the second parent worked full-time or part-time related to power distance. The same database also registered the frequency of cases in which one parent worked full-time and the other looked after the children full-time. This percentage related positively to MAS. In more masculine cultures, the strict role division between a father who earns the family income and a mother who handles the household is relatively more common.18

Studies of schoolchildren in the United States asked boys and girls why they chose the games they played. Boys chose games allowing them to compete and excel; girls chose games for the fun of being together and for not being left out. Repeating these studies in the Netherlands, Dutch researcher Jacques van Rossum found no significant differences in playing goals between boys and girls; thinking he made an error, he tried again, but with the same negative result. Child socialization in the feminine Dutch culture differs less between the sexes.19

The family context in Figure 5.4 depends also on individualism-collectivism. Individualist societies include one-parent families in which role models are incomplete or in which outsiders perform the missing functions. Collectivist societies maintain extended family links, and the center of authority could very well be the grandfather as long as he is still alive, with the father as a model of obedience.

Chapter 4 mentioned as well a massive study by David Buss and his associates regarding the selection of marriage partners in thirty-seven countries. Preferences were strongly related to individualism and collectivism, but further analysis showed that certain differences between the preferences of brides and grooms were related to MAS. Masculine cultures tended to show a double morality in which the chastity and the industriousness of the partner were considered important only by the men. In feminine cultures, they were seen as equally important or unimportant by brides and grooms alike.20

In 1993 a Japanese market research agency, Wacoal, asked young working women in eight Asian capital cities for their preferred characteristics of husbands and of steady boyfriends. In the masculine cultures, husbands should be healthy, wealthy, and understanding, while boyfriends should exhibit personality, affection, intelligence, and a sense of humor. In the more feminine cultures, there was hardly any difference between the preferred characteristics of husbands and of boyfriends. If we see the boyfriend as the symbol of love and the husband as the symbol of family life, this means that in the masculine countries, love and family life were more often seen as separate, whereas in the feminine countries, they were expected to coincide. In the feminine countries, the husband was the boyfriend. A unique aspect of this analysis was that the comparison with the IBM data was made exclusively across Asian countries, showing that the masculinity-femininity dimension could also be validated without including European countries.21

U.S. anthropologist Margaret Mead once observed that in the United States boys become less attractive sex partners by career failure, girls by career success.22 In Japan a woman’s marriage chances diminish if she has a career of her own.

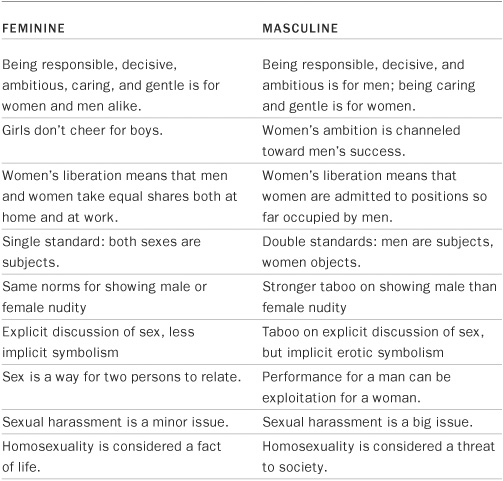

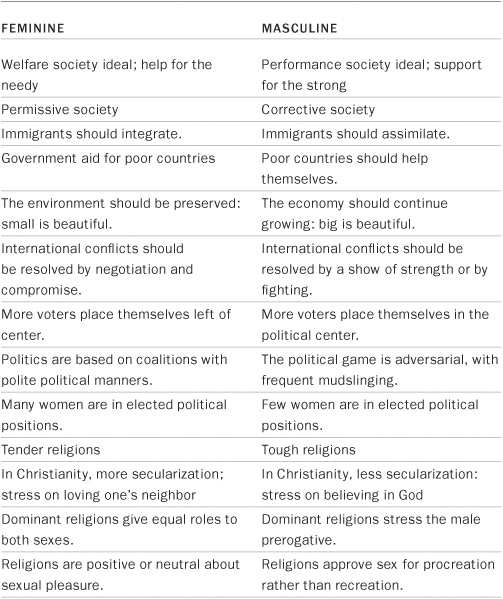

Table 5.2 summarizes the key issues described so far on which masculine and feminine societies tend to differ.

The Wacoal survey also asked young working women in eight Asian cities whether they thought certain characteristics applied to men, to women, or to both. Answers differed between masculine and feminine countries. In the more masculine countries, sense of responsibility, decisiveness, liveliness, and ambitiousness were considered characteristics for men only, while caring and gentleness were seen as for women only. In the more feminine cultures, all these terms were considered as applying to both genders.23

Whereas gender roles in the family strongly affect the values about appropriate behavior for boys and for girls, they do not have immediate implications for the distribution of gender roles in the wider society. As argued earlier in this chapter, men, being on average taller and stronger and free to get out, have traditionally dominated in social life outside the home in virtually all societies. Only exceptional and usually upper-class women had the means to delegate their child-rearing activities to others and to step into a public role. If women entered dominant positions in society at all, this was mostly after the age of forty-five, when their mother status changed into grandmother status. Unmarried women were, and still are, rare in traditional societies and often discriminated against.

TABLE 5.2 Key Differences Between Feminine and Masculine Societies

I: General Norm and Family

The much greater liberty of choice among social roles that women in modern industrialized societies enjoy, beyond those of wife, mother, and housekeeper, is a recent phenomenon. Its impact on the distribution of gender roles outside the home follows more slowly. Therefore, a country’s position on the masculinity-femininity scale need not be closely related to women’s activities outside the family sphere. Economic possibilities and necessities play a bigger role in this respect than values.

A masculine gender role model is pictured in the following description of a popular U.S. movie:

Lucas, a 14-year-old boy, is unlike other kids. He’s slight, inquisitive, and something of a loner, more interested in science and symphonies than in football and parties. But when he meets Maggie, a lovely 16-year-old girl who has just moved to town, things change. They become friends—but for Lucas it is more than friendship.

During the summer they seem to have the same idea: football players and cheerleaders are superficial; but when school begins, Maggie shows an increasing interest in this side of school life, leaving Lucas out in the cold. He watches from the sidelines as Maggie becomes a cheerleader and starts dating Cappie Roew, the captain of the football team.

Suddenly, Lucas wants to “belong,” and in his attempt to win back Maggie, risks life and limb in the game of football. . . .24

Mainstream movies are modern myths—they create hero models according to the dominant culture of the society in which they are made. Both Lucas and Maggie in this movie go through a rite of passage toward their rightful roles in a society in which men fight while playing football and girls stand adoringly and adorably by on the sidelines as cheerleaders.

Femininity should not be confused with feminism. Feminism is an ideology, either organized or not, that wants to change the role of women in society. The masculinity-femininity dimension is relevant to this ideology because across countries we find a more masculine and a more feminine form of feminism. The masculine form claims that women should have the same possibilities that men have. In terms of Figure 5.2, it wants to move the female line up toward the male line; this could also be achieved by moving the entire society toward the right. The feminine form wants to change society, men included. It calls for not only women’s liberation but men’s lib as well. In Figure 5.2 this could be achieved by moving the male line downward toward the female line or by moving the entire society toward the left.

Obviously, a country’s position on the masculinity-femininity scale also affects its norms about sexual behavior.25 Feelings about sex and ways in which sex is practiced and experienced are culturally influenced. Although individuals and groups within countries differ, too, women and men are affected by the written and unwritten norms of their country’s culture.

The basic difference in sexual norms between masculine and feminine cultures follows the pattern of Figure 5.2. Masculine countries tend to maintain different standards for men and for women: men are the subjects, women the objects. In the section on family, we already found this double moral standard in masculine cultures with regard to the chastity of brides: women should be chaste, but men need not. It can also be noticed in norms about nudity in photos and movies: the taboo on showing naked men is much stronger than on showing naked women. Feminine cultures tend to maintain a single standard—equally strict or equally loose—for both sexes, and no immediate link is felt between nudity and sexuality.

Sex is more of a taboo subject in masculine than in feminine cultures. This is evident in information campaigns for the prevention of AIDS, which in feminine countries tend to be straightforward, whereas in masculine countries they are restricted by what can be said and what cannot. Paradoxically, the taboo also makes the subject more attractive, and there is more implicit erotic symbolism in TV programs and advertising in masculine than in feminine countries.

Double standards breed a stress on sexual performance: “scoring” for men, and a feeling of being exploited for women. In single-standard feminine countries, the focus for both is primarily on the relationship between two persons.

In the 1980s Geert was involved in a large survey study on organizational cultures in Denmark and the Netherlands.26 The questionnaire contained among other items a list of possible reasons for dismissal. In a feedback session in Denmark, Geert asked respondents why nobody in their company had considered “a married man having sexual relationships with a subordinate” as a valid reason for the man’s dismissal. A woman stood up and said, “Either she likes it, and then there is no problem, or she doesn’t like it, and then she will tell him to go to hell.” There are two pertinent assumptions in this answer: (most) Danish subordinates will not hesitate to speak up to their bosses (small power distance), and (most) male Danish bosses will “go to hell” if told so by a female subordinate (femininity).

In a study of “sexual harassment” in four countries in the 1990s, Brazilian students of both sexes differed from their colleagues in Australia, the United States, and Germany. They saw sexual harassment less as an abuse of power, less as related to gender discrimination, and more as a relatively harmless pastime.27 Brazil in the IBM research scored lower on MAS than the three other countries (49, versus 61, 62, and 66, respectively).

Attitudes toward homosexuality are also affected by the degree of masculinity in the culture. In a comparison among Australia, Finland, Ireland, and Sweden, it was found that young homosexuals had more problems accepting their sexual orientation in Ireland and Australia, less in Finland, and least in Sweden. This is the order of the countries on MAS. Homosexuality tends to be felt as a threat to masculine norms and rejected in masculine cultures; this attitude is accompanied by an overestimation of its frequency. In feminine cultures, homosexuality is more often considered a fact of life.28

Culture is heavy with values, and values imply judgment. The issues in this section are strongly value-laden. They are about moral and immoral, decent and indecent behavior. The comparisons offered should remind us that morality is in the eye of the beholder, not in the act itself. There is no one best way, neither in social nor in sexual relationships; any solution is the best according to the norms that come with it.

Table 5.3 follows on Table 5.2 and summarizes the key issues from the past two sections on which masculine and feminine societies were shown to differ.

A Dutch management consultant taught part of a course for Indonesian middle managers from a public organization that operated all over the archipelago. In the discussion following one of his presentations, a Javanese participant made a particularly lucid comment, and the teacher praised him openly. The Javanese responded, “You embarrass me. Among us, parents never praise their children to their face.”29

This anecdote illustrates two things. First, it demonstrates how strong, at least in Indonesia, is the transfer of behavior models from the family to the school situation, the teacher being identified with the father. Second, it expresses the virtue of modesty in the Javanese culture to an extent that even surprised the Dutchman. Indonesia is a multiethnic country, one for which national culture scores may be misleading. Indonesians agree that especially on the tough-tender dimension, ethnic groups within the country vary considerably, with the Javanese taking an extreme position toward the tender side. The Dutch consultant said that even some of the other Indonesians were surprised by the Javanese’s feelings. A Batak from the island of Sumatra said that he now understood why his Javanese boss never praised him when he himself felt that praise should have been due. In feminine cultures, teachers will rather praise weaker students, in order to encourage them, than openly praise good students. Awards for excellence—whether for students or for teachers—are not popular; in fact, excellence is a masculine term.30

TABLE 5.3 Key Differences Between Feminine and Masculine Societies

II: Gender and Sex

For a number of years Geert taught U.S. students in a semester-long program of European studies at a Dutch university. To some of the Americans, he gave the assignment to interview Dutch students about their goals in life. The Americans were struck by the fact that the Dutch seemed much less concerned with grades than they expected. Passing was considered enough; excelling was not an openly pronounced goal. Gert Jan’s experiences with students from all over the world are similar. Students from masculine countries may ask to take an exam again after passing with a mediocre grade—Dutch students almost never do so. Such experiences in teaching at home and abroad and discussions with teachers from different countries have led us to conclude that in the more feminine cultures, the average student is considered the norm, while in more masculine countries, the best students are the norm. Parents in these masculine countries expect their children to try to match the best. The “best boy in class” in the Netherlands is a somewhat ridiculous figure.31

This difference is noticeable in classroom behavior. In masculine cultures, students try to make themselves visible in class and compete openly with each other (unless collectivist norms put a limit to this; see Chapter 4).

In feminine countries, assertive behavior and attempts at excelling are easily ridiculed. Excellence is something one keeps to oneself; it easily leads to jealousy. Gert Jan remembers being told by a classmate when he was fourteen, “We know you are smart—but you don’t have to show it all the time.” When he moved to Lausanne, in Switzerland, the following year, he was admired, not rebuked, for being clever.

In the feminine Scandinavian countries, people call their own attitude in this regard the Law of Jante (Janteloven). The Law of Jante, a nickname chosen for a small Danish town, was codified in the 1930s by the Danish-born Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose, and in an English translation it runs as follows:

You should not believe that

you are anything

you are just as much as us

you are wiser than us

you are better than us

you know more than we do

you are more than we are

or that you are good at anything

You should not laugh at us

You should not think

that anybody likes you

or that you can teach us anything.32

Failing in school is a disaster in a masculine culture. In strongly masculine countries such as Japan and Germany, the newspapers carry reports each year about students who killed themselves after failing an examination. In a 1973 insider story, a Harvard Business School graduate reported four suicides—one teacher, three students—during his time at this elite American institution.33 Failure in school in a feminine culture is a relatively minor incident. When young people in these cultures take their lives, it tends to be for reasons unrelated to performance.

Competitive sports play an important role in the curriculum in countries such as Britain and the United States. To a prominent U.S. sports coach the dictum is attributed, “Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing,”34 which doesn’t encourage friendly encounters in sports. In most other European countries, sports are extracurricular and not a part of the school’s main activities.

In an imaginative research project, ten- to fifteen-year-old children from five countries were shown a picture of one person sitting on the ground, with another standing over him saying, “Go ahead and fight back if you can!” They were asked to choose one of eight responses from a card. Aggressive answers were: “You’ve hit me. Now I’m going to teach you a lesson,” “I’ll tell the teacher,” “We are not friends anymore,” and “You’ll get caught by the police!” Appeasing answers were: “We don’t have to fight,” “Let’s talk it over,” “Let’s not fight. Let’s be friends,” “I’m sorry. I was wrong,” and “What if somebody gets hurt by fighting?”35 An aggressive answer was chosen by 38 percent of the children in Japan, 26 percent in Britain, 22 percent in Korea, 18 percent in France, and 17 percent in Thailand. This outcome almost exactly followed the countries’ MAS scores.36 It clearly shows the different socializing of children with regard to aggression. Another study, this time among university students in six countries, contained a question asking whether children in their country were allowed to express aggression. The percentages of “yes” answers varied from 61 in the United States to 5 in Thailand and again correlated significantly with MAS.37

The IBM research found Thailand to be the most feminine Asian country. A book about Thai culture by a British-Thai couple notes: “The Thai learns how to avoid aggression rather than how to defend himself against it. If children fight, even in defense, they are usually punished. The only way to stay out of trouble is to flee the scene.”38

Following the story at the beginning of this chapter about Geert’s job interview, we commented that U.S. applicants tend to oversell and Dutch applicants to undersell themselves. There is confirming evidence for this observation from two studies in a school or learning context.

In the first study, some eight hundred U.S. and eight hundred Dutch youngsters, aged eleven to eighteen, completed questionnaires about their personal competencies and problems. The Americans reported many more problems and competencies than the Dutch. Some items on which Americans scored higher were “argues a lot,” “can do things better than most kids,” “stores up unneeded things,” and “acts without thinking.” The only item on which the Dutch scored higher was “takes life easy.” Reports by parents and teachers showed no difference in problem behavior by these children, but U.S. parents rated their children’s competencies higher than Dutch parents did.39 Young people in U.S. society have been socialized to boost their egos: they take both their problems and their competencies seriously.40 Young people in the Netherlands are socialized rather to efface the ego. An earlier comparison between the U.S. and (masculine) Germany had not found such differences.

The second study compared levels of literacy across seven countries. In 1994 representative samples comprising between two thousand and more than four thousand younger and older adults (aged sixteen to sixty-five) all took the same tests to measure their literacy based on three skills: reading, writing, and using numbers. From those with the best results (literacy levels 4 and 5 out of 5), 79 percent of the Americans rated their own skills “excellent,” but only 31 percent of the Dutch did so41—this in spite of the fact that the tests had shown both groups to be equally good.

Criteria for evaluating both teachers and students differ between masculine and feminine cultures. On the masculine side, teachers’ brilliance and academic reputation and students’ academic performance are the dominant factors. On the feminine side, teachers’ friendliness and social skills and students’ social adaptation play a bigger role.

Interviews with teachers suggest that in masculine countries, job choices by students are strongly guided by perceived career opportunities, while in feminine countries, students’ intrinsic interest in the subject plays a bigger role.

In feminine countries, men and women more often follow the same academic curricula, at least if the country is wealthy. In poor countries, boys almost always get priority in educational opportunities.42

Different job choices by women and men can be partly explained by differences in perceptual abilities. Psychologists studying human perception distinguish between field-independent and field-dependent persons.43

Field-independent persons are able to judge whether a line, projected on a wall, is horizontal even if it is put within a frame that is slanted or if they themselves sit on a chair that is slanted. Field-dependent persons are influenced by the position of the frame or the chair. Field-independent persons rely on internal frames of reference; field-dependent persons take their clues from the environment. Therefore, field-independent people tend to have better analytical skills, and field-dependent people tend to have better social and linguistic skills. Men are more often field-independent, women field-dependent. Masculine cultures tend to score more field-independent, and feminine cultures more field-dependent,44 and there is less difference in perceptual abilities between the genders in feminine than in masculine countries.

Segregation in job choice also determines whether teachers themselves are women or men. In masculine societies, women mainly teach younger children, while men teach at universities. In feminine societies, roles are more mixed and men also teach younger children. Paradoxically, therefore, children in masculine societies are exposed longer to female teachers. The status of these teachers, however, is often low so that they will be antiheroines rather than models for behavior.

Dutch marketing expert Marieke de Mooij studied data on consumer behavior across sixteen affluent European countries.45 She found several significant differences related to the masculinity-femininity dimension. One was the division of buying roles between the genders. In feminine culture countries, a larger share of the family’s food shopping is done by the husband. Other differences relate to the family car. In buying a new car, the husband in a feminine country will involve his partner. In a masculine country, this tends to be the man’s sovereign decision, in which the car’s engine power plays an important role. In feminine cultures, car owners often don’t even know their car’s engine power. The car has often been described as a sex symbol; to many people it certainly is a status symbol. Masculine cultures have relatively more two-car families than feminine cultures; in the latter, husband and wife more often share one family car.

Status purchases in general are more frequent in masculine cultures. People in masculine cultures buy more expensive watches and more real jewelry; they more often consider foreign goods as more attractive than local products. They more often fly business class on pleasure trips.

Feminine cultures spend more on products for the home. More people in these cultures take their “home” (their caravan, RV, or trailer) with them on vacation. They spend more on do-it-yourself carpentry, on making their own dresses, and, for smokers, on rolling their own cigarettes. Coffee is a symbol of togetherness; people in feminine cultures own more electric coffeemakers, guaranteeing that coffee in the home is always ready.

People in feminine cultures buy more fiction books, and people in masculine cultures more nonfiction. U.S. author Deborah Tannen has pointed to differences between male and female discourse: more “report talk” (transferring information) for men, more “rapport talk” (using the conversation to exchange feelings and establish a relationship) for women.46 De Mooij’s data show that at the culture level, too, masculine readers are more concerned with data and facts; readers from feminine cultures are more interested in the story behind the facts.

In Chapter 4 we saw that survey data related the frequency of Internet use to IDV; the Net is basically an individualistic tool. However, the use of the Internet for private (nonwork) purposes correlates even more with low MAS. Both the Internet and e-mail can be used for “rapport” purposes and for “report” purposes; the former usage is more frequent in less masculine societies.47

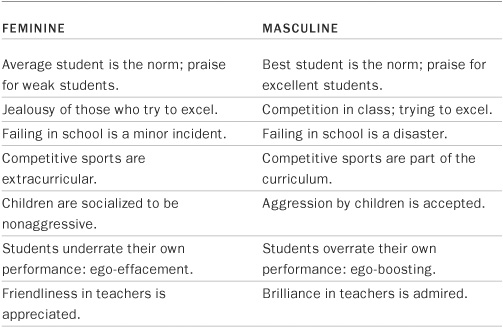

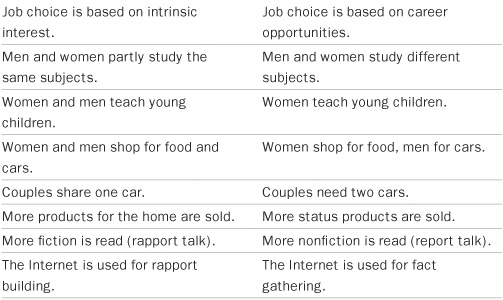

Table 5.4 is a continuation of Tables 5.2 and 5.3, summarizing the key issues from the past two sections.

The Dutch manufacturing plant of a major U.S. corporation had lost three Dutch general managers in a period of ten years. To the divisional vice president in the United States, all these men had come across as “softies.” They hesitated to implement unpopular measures with their personnel, claiming the resistance of their works council—a body elected by the employees and required by Dutch law that the vice president did not like anyway. After the third general manager had left, the vice president stepped in personally and nominated the plant controller as his successor—ignoring strong warnings by the human resources manager. To the vice president, this controller was the only “real man” in the plant management team. He had always supported the need for drastic action, disregarding its popularity or unpopularity. In his reports he had indicated the weak spots. He should be able to maintain the prerogatives of management, without being sidetracked by this works council nonsense.

TABLE 5.4 Key Differences Between Feminine and Masculine Societies

III: Education and Consumer Behavior

The new plant general manager proved the biggest disaster ever. Within six months he was on sick leave and the organization was in a state of chaos. Nobody in the plant was surprised. Everyone had known the controller as a congenial but weak personality, who had compensated for his insecurity by using powerful language toward the American bosses. The assertiveness that impressed the American vice president was recognized within the Dutch environment as bragging. As a general manager he received no cooperation from anyone, tried to do everything himself, and suffered a nervous breakdown in short order. Thus, the plant lost both a good controller and another general manager. Both the plant and the controller were victims of a culturally induced error of judgment.

Historically, management is an Anglo-Saxon concept, developed in masculine British and American cultures. The English—and international—word management comes from the Latin manus, or “hand”; the modern Italian word maneggiare means “handling.” In French, however, the Latin root is used in two derivations: manège (a place where horses are drilled) and ménage (household); the former is the masculine side of management, the latter the feminine side. Classic American studies of leadership distinguished two dimensions: initiating structure versus consideration, or concern for work versus concern for people.48 Both are equally necessary for the success of an enterprise, but the optimal balance between the two differs for masculine and feminine cultures.

A Dutchman who had worked with a prestigious consulting firm in the United States for several years joined the top management team of a manufacturing company in the Netherlands. After a few months he commented on the different function of meetings in his present job compared with his previous one. In the Dutch situation, meetings were occasions when problems were discussed and common solutions were sought; they served for making consensus decisions.49 In the U.S. situation as he had known it, meetings were opportunities for participants to assert themselves, to show how good they were. Decisions were made by individuals elsewhere.

The masculinity-femininity dimension affects ways of handling industrial conflicts. In the United States as well as in other masculine cultures such as Britain and Ireland, there is a feeling that conflicts should be resolved by a good fight: “Let the best man win.” The industrial relations scene in these countries is marked by such fights. If possible, management tries to avoid having to deal with labor unions at all, and labor union behavior justifies management’s aversion. In the United States, the relationships between labor unions and enterprises are governed by extensive contracts serving as peace treaties between both parties.50

In feminine cultures such as the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark, there is a preference for resolving conflicts by compromise and negotiation. In France, which scored moderately feminine in the IBM studies, there is occasionally a lot of verbal insult, both between employers and labor and between bosses and subordinates, but behind this seeming conflict there is a typically French “sense of moderation,” which enables parties to continue working together while agreeing to disagree.51

Organizations in masculine societies stress results and try to reward achievement on the basis of equity—that is, to everyone according to performance. Organizations in feminine societies are more likely to reward people on the basis of equality (as opposed to equity)—that is, to everyone according to need.

The idea that small is beautiful is a feminine value. The IBM survey itself as well as public opinion survey data from six European countries showed that a preference for working in larger organizations was strongly correlated with MAS.52

The place that work is supposed to take in a person’s life differs between masculine and feminine cultures. A successful early twentieth-century U.S. inventor and businessman, Charles F. Kettering, is reputed to have said:

I often tell my people that I don’t want any fellow who has a job working for me; what I want is a fellow whom a job has. I want the job to get the fellow and not the fellow to get the job. And I want that job to get hold of this young man so hard that no matter where he is the job has got him for keeps. I want that job to have him in its clutches when he goes to bed at night, and in the morning I want that same job to be sitting on the foot of his bed telling him it’s time to get up and go to work. And when a job gets a fellow that way, he’s sure to amount to something.53

Kettering refers to a “young man” and not to a “young woman”—his is a masculine ideal. It would certainly not be popular in more feminine cultures; there, such a young man would be considered a workaholic. In a masculine society, the ethos tends more toward “live in order to work,” whereas in a feminine society, the work ethos would rather be “work in order to live.”

A public opinion survey in the European Union contained the question “If the economic situation were to improve so that the standard of living could be raised, which of the following two measures would you consider to be better: Increasing the salaries (for the same number of hours worked) or reducing the number of hours worked (for the same salary)?” Preferences varied from 62 percent in favor of salary in Ireland to 64 percent in favor of fewer hours worked in the Netherlands. The differences (percent preferring salary minus percent preferring fewer hours) were significantly correlated with MAS more than with national wealth. Although respondents in the poorer countries stressed the need for increasing salaries more, values (MAS) played a stronger role.54

Boys in a masculine society are socialized toward assertiveness, ambition, and competition. When they grow up, they are expected to aspire to career advancement. Girls in a masculine society are polarized between some who want a career and most who don’t. The family within a feminine society socializes children toward modesty and solidarity, and in these societies both men and women may or may not be ambitious and may or may not want a career.

The feminine side of management opens possibilities in any culture for women managers, who may be better able to combine manège and ménage than men. U.S. researcher Anne Statham interviewed matched groups of female and male U.S. managers and their secretaries, and she concluded that the women predominantly saw job and people orientation as interdependent, while to the men they were each other’s opposites.55

Worldwide there is no relationship between the masculinity or femininity of a society’s culture and the distribution of employment over men and women. An immediate relationship between a country’s position on this dimension and the roles of men and women exists only within the home. Outside the home, men have historically dominated, and only in the wealthier countries—and this only recently in history—have women in any numbers been sufficiently freed from other constraints to be able to enter the worlds of work and politics as men’s equals. Lower-class women have entered work organizations before, but only in low-status, low-paid jobs—not out of a need for self-fulfillment, but rather out of a need for material survival of the family. Statistics therefore show no relationship between a country’s share of women working outside the home per se and its degree of femininity. Feminine wealthier countries do have more working women in higher-level technical and professional jobs.56

Many jobs in business demand few skills and cause a qualitative under-employment of people. A need for “humanization of work” has been felt in industrialized masculine as well as feminine countries, but what is considered a humanized job depends on one’s model of what it means to be human. In masculine cultures, a humanized job should give more opportunities for recognition, advancement, and challenge. This is the principle of job enrichment as once defended, among others, by U.S. psychologist Frederick Herzberg.57 An example is making workers on simple production tasks also responsible for the setting up and preventive maintenance of their machines, tasks that had previously been reserved for more highly trained specialists. Job enrichment represents a “masculinization” of unskilled and semiskilled work that, as shown earlier in this chapter, has a relatively “feminine” occupation culture.

In feminine cultures, a humanized job should give more opportunities for mutual help and social contacts. Classic experiments were conducted in the 1970s by the Swedish car and truck manufacturers Saab and Volvo featuring assembly by autonomous work groups. These groups represent a reinforcement of the social side of the job: its “femininization.” In 1974 six U.S. Detroit automobile workers, four men and two women, were invited to work for three weeks in a group assembly system in the Saab-Scania plant in Södertälje, Sweden. The experiment was covered by a U.S. journalist who reported on the Americans’ impressions. All four men and one of the women said they continued to prefer the U.S. work system. “Lynette Stewart chose Detroit. In the Cadillac plant where she works, she is on her own and can make her own challenge, while at Saab-Scania she has to consider people in front and behind her.”58 Of course, this was precisely what made the group assembly system attractive to the Swedes.

Based on their cultural characteristics, masculine and feminine countries excel in different types of industries. Industrially developed masculine cultures have a competitive advantage in manufacturing, especially in large volume: doing things efficiently, well, and fast. They are good at the production of big and heavy equipment and in bulk chemistry. Feminine cultures have a relative advantage in service industries such as consulting and transportation, in manufacturing according to customer specification, and in handling live matter such as in high-yield agriculture and biochemistry. There is an international division of labor in which countries are relatively more successful in activities that fit their population’s cultural preferences than in activities that go against these preferences. Japan has a history of producing high-quality consumer electronics; Denmark and the Netherlands have a history of excellence in services, in agricultural exports, and in biochemical products such as enzymes and penicillin.

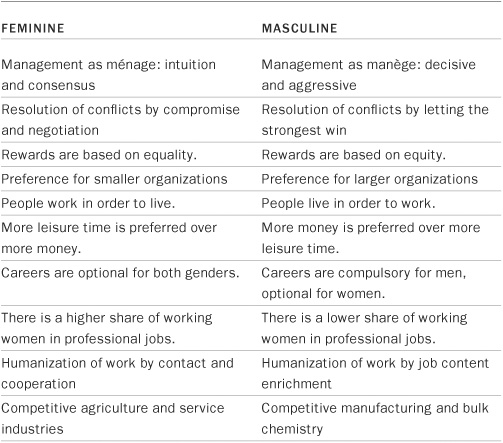

Table 5.5 is a continuation of Tables 5.2, 5.3, and 5.4, summarizing the key issues from the past section on which masculine and feminine societies differ.

TABLE 5.5 Key Differences Between Feminine and Masculine Societies

IV: The Workplace

National value patterns are present not only in the minds of ordinary citizens but, of course, also in those of political leaders, who also grew up as children of their societies. As a matter of fact, people are usually elected or co-opted to political leadership because they are supposed to stand for certain values dear to citizens.

Politicians translate values dominant in countries into political priorities. The latter are most clearly visible in the composition of national government budgets. The masculinity-femininity dimension affects priorities in the following areas:

Solidarity with the weak versus reward for the strong

Solidarity with the weak versus reward for the strong

Aid to poor countries versus investing in armaments

Aid to poor countries versus investing in armaments

Protection of the environment versus economic growth

Protection of the environment versus economic growth

Masculine culture countries strive for a performance society; feminine countries for a welfare society. They get what they pay for: in 1994–95, across ten developed industrial countries for which data were available, the share of the population living in poverty varied from 4.3 percent in feminine Norway to 17.6 percent in masculine Australia. In the period 1992–2002, across eighteen developed countries, the share of the population earning less than half the median income varied from 5.4 percent in Finland to 17.0 percent in the United States. The share of functional illiterates (people who completed school but in actual fact cannot read or write) across thirteen developed countries varied from 7.5 percent in Sweden to 22.6 percent in Ireland.59 In all three cases the percentages were strongly correlated with MAS.60

In criticisms by politicians and journalists from masculine countries such as the United States and Great Britain versus feminine countries such as Sweden and the Netherlands, strong and very different value positions appear. There is a common belief in, for example, the United States that economic problems in Sweden and the Netherlands are due to high taxes, while there is a belief in feminine European countries that economic problems in the United States are due to too much tax relief for the rich. Tax systems, however, do not just happen: they are created by politicians as a consequence of preexisting value judgments. Most Swedes feel that society should provide a minimum quality of life for everyone. It is normal that the financial means to that end are collected from those in society who have them. Even conservative politicians in northwestern Europe do not basically disagree with this view, only with the extent to which it can be realized.

The northwestern European welfare state is not a recent invention. The French philosopher Denis Diderot, who visited the Netherlands in 1773–74, described both the high taxes and the absence of poverty as a consequence of welfare payments, good medical care for all, and high standards of public education: “The poor in hospitals are well cared for: They are each put in a separate bed.”61

The performance versus welfare antithesis is reflected in views about the causes of poverty. A survey in the European Union countries included the following question: “Why, in your opinion, are there people who live in need? Here are four opinions; which is the closest to yours? (1) Because they have been unlucky; (2) Because of laziness and lack of willpower; (3) Because there is much injustice in our society; (4) It is an inevitable part of modern progress.” Across twelve European Union member states, the percentages attributing poverty to having been unlucky varied from 14 percent in Germany to 33 percent in the Netherlands; they were significantly negatively correlated with MAS.62 The percentages attributing poverty to laziness varied from 10 percent in the Netherlands to 25 percent in Greece and Luxembourg; these results were positively correlated with MAS. In masculine countries, more people believe that the fate of the poor is their own fault; that if they would work harder, they would not be poor; and that the rich certainly should not pay to support them.

Attitudes toward the poor are replicated in attitudes toward lawbreakers. A public opinion poll in nine European countries in 1981 asked to what extent a number of debatable acts were justifiable: joyriding, using soft drugs, accepting bribes, prostitution, divorce, and suicide. The answers were summarized in an index of permissiveness, which across countries was strongly correlated with femininity. Mother is less strict than father.63

The masculinity-femininity dimension is also related to opinions about the right way of handling immigrants. In general, two opposing views are found. One defends assimilation (immigrants should give up their old culture), the other integration (immigrants should adapt only those aspects of their culture and religion that conflict with their new country’s laws). In a public opinion survey covering fourteen European Union countries in 1997, the public preference for integration over assimilation was strongly negatively correlated with MAS; there was a weaker additional correlation with gross national income per capita.64 Respondents in more masculine and poorer countries required assimilation; those in feminine and wealthier countries favored integration. In Chapter 4 we associated “respect for other cultures” with universalism, citing 2008 Eurobarometer data. Europeans in twenty-six countries were asked to choose “the most important values for you personally” (three out of a list of twelve). One of these values was “respect for other cultures.” Differences among countries in percentages of respondents choosing this answer related both to IDV and to low MAS.65

In wealthy countries, the value choice between reward for the strong and solidarity with the weak is also reflected in the share of the national budget spent on development assistance to poor countries. The percentage of their GNI that governments of rich countries have allocated to helping poor ones varies widely. In 2005 the United States spent 0.22 percent of its GNI, while Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden each spent more than 0.7 percent.66 The proportions spent are unrelated to the wealth of the donor countries. What does correlate with a high aid quote is a feminine national value system.67

The Internet Journal Foreign Policy has computed for twenty-one rich countries a Commitment to Development Index (CDI) by measuring not only flows of aid money but also positive and negative impacts of other policies: trade flows, migration, investment, peacekeeping, and environmental policies. Again the CDI was significantly (negatively) correlated only with MAS. The correlation was weaker than for money flows, as policies on behalf of welfare in the home country sometimes conflict with policies on help abroad.68

Countries that spend little money on helping the poor in the world probably spend more on armaments. However, reliable data on defense spending are difficult to come by, as both the suppliers and the purchasers of arms have a vested interest in secrecy. The only conclusion we could draw from the available figures was that among donor countries, the less wealthy spent a larger share of their budgets on supplying arms than the wealthier ones.69 Guns had priority over butter.

Masculine countries tend to (try to) resolve international conflicts by fighting; feminine countries by compromise and negotiation (as in the case of work organizations). A striking example is the difference between the handling of the Åland crisis and of the Falkland crisis.

The Åland islands are a small archipelago halfway between Sweden and Finland; as part of Finland they belonged to the tsarist Russian Empire. When Finland declared itself independent from Russia in 1917, the thirty thousand inhabitants of the islands in majority wanted to join Sweden, which had ruled them before 1809. The Finns then arrested the leaders of the pro-Swedish movement. After emotional negotiations in which the newly created League of Nations participated, all parties in 1921 agreed with a solution in which the islands remained Finnish but with a large amount of regional autonomy.

The Falkland Islands are also a small archipelago disputed by two nations: Great Britain, which has occupied the islands since 1833, and nearby Argentina, which has claimed rights on them since 1767 and tried to get the United Nations to support its claim. The Falklands are about eight times as large as the Ålands but with less than one-fifteenth of the Ålands’ population: about 1,800 poor sheep farmers. The Argentinean military occupied the islands in April 1982, whereupon the British sent an expeditionary force that chased the occupants, at the cost of (officially) 725 Argentinean and 225 British lives and enormous financial expense. The economy of the islands, dependent on trade relations with Argentina, was severely jeopardized.

What explains the difference in approach and in results between these two remarkably similar international disputes? Finland and Sweden are both feminine cultures; Argentina and Great Britain are both masculine. The masculine symbolism in the Falkland crisis was evident in the language used on either side. Unfortunately, the sacrifices resolved very little. The Falklands remain a disputed territory needing constant British subsidies and military presence; the Ålands have become a prosperous part of Finland, attracting many Swedish tourists.

In 1972 an international team of scientists nicknamed the Club of Rome published a report titled Limits to Growth, which was the first public recognition that continued economic growth and conservation of our living environment are fundamentally conflicting objectives. Their report has been attacked on details, and for a time the issues it raised seemed less urgent. Its basic thesis, however, has never been refuted, and at least in our view, it is irrefutable. Nothing can grow forever, and ignoring this basic fact is the principal weakness of present-day economics. Governments have to make painful choices, and apart from local geographic and ecological constraints, these choices will be made according to the values dominant in a country. Governments in masculine cultures are more likely to give priority to growth and sacrifice the living environment for this purpose. Governments in feminine cultures are more likely to reverse priorities.70 As environmental problems cross borders and oceans, international diplomacy is needed for solutions. A worldwide approach was laid down in the Kyoto Protocol, the result of a United Nations convention in 1997. Then U.S. president George W. Bush, following his election in 2001, showed his masculine priorities by withdrawing from it. Former U.S. vice president Al Gore in 2006 put the environment back on the U.S. public agenda with his film An Inconvenient Truth, and U.S. president Barack Obama in 2008 committed himself to a new leading role for the United States in this field—which, however, will be an uphill struggle within U.S. politics.

The 1990–93 World Values Survey asked representative samples of the populations to place their political views on a scale from “left” to “right.” Voters from masculine countries placed themselves mostly in the center; voters from feminine countries were slightly more to the left. Few people placed themselves on the right.71

Masculinity or femininity in democratic politics is not just a matter of policy priorities; it is also reflected in the informal rules of the political game. In masculine cultures such as Britain, Germany, and the United States, the style of political discourse is strongly adversarial. This is not a recent phenomenon. In 1876 the Dutch-language newspaper De Standaard reported that “the American political parties eschewed no means to sling mud at their adversaries, in a way which foreigners find disgusting.”72 This statement is still valid today. In feminine cultures such as the Nordic countries and the Netherlands, governments are nearly always coalitions between different parties that treat each other relatively gently.

In democratic countries, cultural masculinity and femininity influence the likelihood that elected delegates and members of government will be women. In 2006, among twenty-four established parliamentary democracies, percentages of women in parliament were below 20 in Britain, France, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, and the United States; they were over 30 in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, and Sweden. Female ministers in 2005 were fewer than 20 percent in France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Portugal, Switzerland, and the United States; they were more than 30 percent in Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and Sweden.73 This is mainly a masculine-feminine split, although the low percentages for France and Portugal and the high percentages for Austria and Germany suggest that power distance also plays a role. However, women do advance more easily in politics than in work organizations. The election process reacts faster to changes in society than co-optation processes in business. Capable women in business organizations still have to wait for aged gentlemen to retire or die. Possibly politics as a public good attracts more women than does business as private achievement.

The issues related to the masculinity-femininity dimension are central to any religion. Masculine cultures worship a tough God or gods who justify tough behavior toward fellow humans; feminine cultures worship a tender God or gods who demand caring behavior toward fellow humans.

Christianity has always maintained a struggle between tough, masculine elements and tender, feminine elements. In the Christian Bible as a whole, the Old Testament reflects tougher values (an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth), while the New Testament reflects more tender values (turn the other cheek). God in the Old Testament is majestic. Jesus in the New Testament helps the weak and suffers. Catholicism has produced some very masculine, tough currents (Templars, Jesuits) but also some feminine, tender ones (Franciscans); outside Catholicism we also find groups with strongly masculine values (such as the Mormons) and groups with very feminine values (such as the Quakers and the Salvation Army). On average, countries with a Catholic tradition tend to maintain more masculine values and those with Protestant traditions more feminine values.74