In a peaceful revolution—the last revolution in Swedish history—the nobles of Sweden in 1809 deposed King Gustav IV, whom they considered incompetent, and surprisingly invited Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, a French general who served under their enemy Napoleon, to become king of Sweden. Bernadotte accepted and became King Charles XIV John; his descendants have occupied the Swedish throne to this day. When the new king was installed, he addressed the Swedish parliament in their language. His broken Swedish amused the Swedes, and they roared with laughter. The Frenchman who had become king was so upset that he never tried to speak Swedish again.

In this incident Bernadotte was a victim of culture shock: never in his French upbringing and military career had he experienced subordinates who laughed at the mistakes of their superior. Historians tell us he had more problems adapting to the egalitarian Swedish and Norwegian mentality (he later became king of Norway as well) and to his subordinates’ constitutional rights. He was a good learner, however (except for language), and he ruled the country as a highly respected constitutional monarch until 1844.

One of the aspects in which Sweden differs from France is the way society handles inequality. There is inequality in any society. Even in the simplest hunter-gatherer band, some people are bigger, stronger, or smarter than others. Further, some people have more power than others: they are more able to determine the behavior of others than vice versa. Some people acquire more wealth than others. Some people are given more status and respect than others.

Physical and intellectual capacities, power, wealth, and status may or may not go together. Successful athletes, artists, and scientists usually enjoy status, but only in some societies do they enjoy wealth as well, and rarely do they have political power. Politicians in some countries can enjoy status and power without wealth; businesspeople can have wealth and power without status. Such inconsistencies among the various areas of inequality are often felt to be problematic. In some societies people try to resolve them by making the areas more consistent. Athletes turn professional to become wealthy; politicians exploit their power and/or move on to attractive business positions in order to do the same; successful business-people enter public office in order to acquire status. This trend obviously increases the overall inequalities in these societies.

In other societies the dominant feeling is that it is a good thing, rather than a problem, if a person’s rank in one area does not match his or her rank in another. A high rank in one area should partly be offset by a low rank in another. This process increases the size of the middle class in between those who are on top in all respects and those who lack any kind of opportunity. The laws in many countries have been conceived to serve this ideal of equality by treating everybody as equal regardless of status, wealth, or power, but there are few societies in which reality matches the ideal. The praise of poverty in the Christian Bible can be seen as a manifestation of a desire for equality; the same is true for Karl Marx’s plea for a “dictatorship of the proletariat.”

Not only Sweden and France but other nations as well can be distinguished by the way they tend to deal with inequalities. The research among IBM employees in similar positions but in different countries has allowed us to assign to each of these countries a score indicating its level of power distance. Power distance is one of the dimensions of national cultures introduced in Chapter 2. It reflects the range of answers found in the various countries to the basic question of how to handle the fact that people are unequal. It derives its name from research by a Dutch experimental social psychologist, Mauk Mulder, into the emotional distance that separates subordinates from their bosses.1

Scores on power distance for fifty countries and three multicountry regions have been calculated from the answers by IBM employees in the same kind of positions on the same survey questions. All questions were of the precoded-answer type so that answers could be represented by a score number: usually 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5. Standard samples composed of respondents from the same mix of jobs were taken from each country. A mean score was computed for each sample (say, 2.53 as the mean score for country X and 3.43 for country Y), or the percentage of people choosing particular answers was computed (say, 45 percent of the sample choosing answer 1 or 2 in country X and 33 percent in country Y). From that data, a table was composed presenting mean scores or percentages for each question and for all countries.

A statistical procedure (factor analysis) was used to sort the survey questions into groups, called factors or clusters, for which the mean scores or percentages varied together.2 This meant that if a country scored high on one of the questions from the cluster, it also could be expected to score high on the others; likewise, it could be expected to score not high but low for questions carrying the opposite meaning. If, on the other hand, a country scored low on one question from the cluster, it also would most likely score low on the others and score high on questions formulated the other way around. If a country scored average on one question from the cluster, it probably would score average on all of them.

One of the clusters found was composed of questions that all seemed to have something to do with power and (in)equality. From the questions in this cluster, we selected the three that were most strongly related.3 From the mean scores of the standard sample of IBM employees in a country on these three questions, a power distance index (PDI) for the country was calculated. The formula developed for this purpose uses simple mathematics (adding or subtracting the three scores after multiplying each by a fixed number, and finally adding another fixed number). The purpose of the formula was (1) to ensure that each of the three questions would carry equal weight in arriving at the final index and (2) to get index values ranging from about 0 for a small-power-distance country to about 100 for a large-power-distance country. Two countries that were added later score above 100.

The three survey items used for composing the power distance index were as follows:

1. Answers by nonmanagerial employees to the question “How frequently, in your experience, does the following problem occur: employees being afraid to express disagreement with their managers?” (mean score on a 1–5 scale from “very frequently” to “very seldom”)

2. Subordinates’ perception of the boss’s actual decision-making style (percentage choosing the description of either an autocratic style or a paternalistic style, out of four possible styles plus a “none of these” alternative)4

3. Subordinates’ preference for their boss’s decision-making style (percentage preferring an autocratic or a paternalistic style, or, on the contrary, a style based on majority vote, but not a consultative style)

Country PDI scores are shown in Table 3.1. For fifty-seven of the countries or regions (see Table 2.2) the scores were calculated directly from the IBM data set. The remaining cases were calculated from replications or based on informed estimates.5 Because of the way the scores were calculated, they represent relative, not absolute, positions of countries: they are measures of differences only. The scores that were based on answers by IBM employees paradoxically contain no information about the corporate culture of IBM: they show only to what extent people from the subsidiary in country X answered the same questions differently from similar people in country Y. The conclusion that the score differences reflect different national cultures is confirmed by the fact that we found the same differences in populations outside IBM (the validation process as described in Chapter 2).

TABLE 3.1 Power Distance Index (PDI) Values for 76 Countries and Regions Based on Three Items in the IBM Database Plus Extensions

For the multilingual countries Belgium and Switzerland, Table 3.1 gives the scores by the two largest language areas. For Canada there is an IBM score for the whole country and a replication-based score for the French-speaking part. The IBM sample for what was once Yugoslavia has been split into Croatia, Serbia, and Slovenia. The other countries in Table 3.1 all have a single score. This does not mean that they are necessarily culturally homogeneous; it means only that the available data did not allow a splitting up into subcultures.

Table 3.1 shows high power distance values for most Asian countries (such as Malaysia and the Philippines), for Eastern European countries (such as Slovakia and Russia), for Latin countries (Latin America, such as Panama and Mexico, and to a somewhat lesser extent Latin Europe, such as France and Wallonia, the French-speaking part of Belgium), for Arabic-speaking countries, and for African countries. The table shows low values for German-speaking countries, such as Austria, the German-speaking part of Switzerland, and Germany; for Israel; for the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden) and the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania); for the United States; for Great Britain and the white parts of its former empire (New Zealand, Ireland, Australia, Canada); and for the Netherlands (but not for Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, which scored quite similar to Wallonia). Sweden scored 31 and France 68. If such a difference existed already two hundred years ago—for which, as will be argued, there is a good case—this explains Bernadotte’s culture shock.

Looking at the three questions used to compose the PDI, you may notice something surprising: questions 1 (employees afraid) and 2 (boss autocratic or paternalistic) indicate the way the respondents perceive their daily work environment. Question 3, however, indicates what the respondents express as their preference: how they would like their work environment to be.

The fact that the three questions are part of the same cluster shows that from one country to another there is a close relationship between the reality one perceives and the reality one desires.6 In countries in which employees are not seen as very afraid and bosses as not often autocratic or paternalistic, employees express a preference for a consultative style of decision making: a boss who, as the questionnaire expressed, “usually consults with subordinates before reaching a decision.”

In countries on the opposite side of the power distance scale, where employees are seen as frequently afraid of disagreeing with their bosses and where bosses are seen as autocratic or paternalistic, employees in similar jobs are less likely to prefer a consultative boss. Instead, many among them express a preference for a boss who decides autocratically or paternalistically; however, some switch to the other extreme—that is, preferring a boss who governs by majority vote, which means that he or she does not actually make the decision at all. In the real-world practices of most organizations, majority vote is difficult to handle, and few people actually perceived their bosses as using this style (bosses who pretend to do so are often accused of manipulation).

In summary, PDI scores inform us about dependence relationships in a country. In small-power-distance countries, there is limited dependence of subordinates on bosses, and there is a preference for consultation (that is, interdependence among boss and subordinate). The emotional distance between them is relatively small: subordinates will rather easily approach and contradict their bosses. In large-power-distance countries, there is considerable dependence of subordinates on bosses. Subordinates respond by either preferring such dependence (in the form of an autocratic or paternalistic boss) or rejecting it entirely, which in psychology is known as counterdependence—that is, dependence but with a negative sign. Large-power-distance countries thus show a pattern of polarization between dependence and counterdependence. In these cases the emotional distance between subordinates and their bosses is large: subordinates are unlikely to approach and contradict their bosses directly.

Power distance can therefore be defined as the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally. Institutions are the basic elements of society, such as the family, the school, and the community; organizations are the places where people work.

Power distance is thus described based on the value system of the less powerful members. The way power is distributed is usually explained from the behavior of the more powerful members, the leaders rather than those led. The popular management literature on leadership often forgets that leadership can exist only as a complement to “subordinateship.” Authority survives only where it is matched by obedience. Bernadotte’s problem was not a lack of leadership on his side; rather, the Swedes had a different conception of the deference due to a ruler from that of the French—and Bernadotte was a Frenchman.

Comparative research projects studying leadership values from one country to another show that the differences observed exist in the minds of both the leaders and those led, but often the statements obtained from those who are led are a better reflection of the differences than those obtained from the leaders. This is because we are all better observers of the leadership behavior of our bosses than we are of ourselves. Besides the questions on perceived and preferred leadership style of the boss—questions 2 and 3 in the PDI—the IBM surveys also asked managers to rate their own style. It appeared that self-ratings by managers resembled closely the styles these managers preferred in their own bosses—but not at all the styles their subordinates perceived them to have. In fact, the subordinates saw their managers in just about the same way as the managers saw their bosses. The moral for managers is: if you want to know how your subordinates see you, don’t try to look in the mirror—that just produces wishful thinking. Turn around 180 degrees and face your own boss.7

In Chapter 2, Table 2.1, six studies were listed, published between 1990 and 2002, that used the IBM questions or later versions of them with other cross-national populations. Five of these, covering between fourteen and twenty-eight countries from the IBM set, produced PDI scores highly significantly correlated with the original IBM scores.8 The sixth got its data from consumers who were not selected on the basis of their relationships to power, who were in very different jobs, or, as in the case of students and housewives, who did not have paid jobs at all. We investigated whether the new scores would justify correcting some of the original IBM scores, and we concluded that the new scores were not consistent enough for this purpose.9 None of the new populations covered as many countries or represented such well-matched samples as the original IBM set. Also, correlations of the original IBM scores with other data, such as consumer purchases, have not become weaker over time.10 One should remember that the scores measured differences between country cultures, not cultures in an absolute sense. The cultures may have shifted, but as long as they shifted together under the influence of the same global forces, the scores remain valid.

Bond’s Chinese Value Survey study among students in twenty-three countries, described in Chapter 2, produced a moral discipline dimension on which the countries positioned themselves largely in the same way as they had done in the IBM studies on power distance (in statistical terms, moral discipline was significantly correlated with PDI).11 Students in countries scoring high on power distance answered that the following were particularly important:

Having few desires

Having few desires

Moderation, following the middle way

Moderation, following the middle way

Keeping oneself disinterested and pure

Keeping oneself disinterested and pure

In unequal societies, ordinary people such as students felt they should not have aspirations beyond their rank.

Students in countries scoring low on power distance, on the other hand, answered that the following were particularly important:

Adaptability

Adaptability

Prudence (carefulness)

Prudence (carefulness)

In more egalitarian societies, where problems cannot be resolved by someone’s show of power, students stressed the importance of being flexible in order to get somewhere.

The GLOBE study, also described in Chapter 2, included items intended to measure a power distance dimension. As we argued, GLOBE’s questions were formulated very differently from ours. Rather than the respondents’ daily terminology, they used researchers’ jargon, making it often difficult for the respondents to guess what the answers meant. From GLOBE’s eighteen dimensions (nine asking respondents to describe their culture “as it is” and nine “as it should be”), no fewer than nine were significantly correlated with our PDI. The strongest correlation of PDI was with the GLOBE dimension in-group collectivism “as is.” There was only a weakly significant correlation between PDI and GLOBE’s power distance “as is,” and there was none at all between PDI and GLOBE’s power distance “should be.”12 In fact, GLOBE’s power distance “as is” and “should be” both correlated more strongly with our uncertainty avoidance index (Chapter 6).13 GLOBE’s power distance presents no alternative for our PDI.

Inequality within a society is visible in the existence of different social classes: upper, middle, and lower, or however one wants to divide them—this varies by country. Classes differ in their access to and their opportunities for benefiting from the advantages of society, one of them being education. A higher education automatically makes one at least middle class. Education, in turn, is one of the main determinants of the occupations to which one can aspire, so that in practice in most societies, social class, education level, and occupation are closely linked. In Chapter 1 all three have been listed as sources of our mental software: there are class, education, and occupation levels in our culture, but they are mutually dependent.

The data used for the computation of the PDI in IBM were from employees in various occupations and, therefore, from different education levels and social classes. However, the mix of occupations studied was kept constant for all countries. Comparisons of countries or regions should always be based on people in the same set of occupations. One should not compare Spanish engineers with Swedish secretaries. The mix of occupations to be compared across all the subsidiaries was taken from the sales and service offices: these were the only activities that could be found in all countries. IBM’s product development laboratories were located in only ten of the larger subsidiaries, and its manufacturing plants in thirteen.

The IBM sales and service people had all completed secondary or higher education and could be considered largely middle class. The same applies to the people in the replication studies. The PDI scores in Table 3.1, therefore, are really expressing differences among middle-class persons in these countries. Middle-class values affect the institutions of a country, such as governments and education systems, more than do lower-class values. This is because the people who control the institutions usually belong to the middle class. Even representatives of lower-class groups, such as union leaders, tend to be better educated or self-educated, and by this fact alone they have adopted some middle-class values. Lower-class parents often have middle-class ambitions for their children.

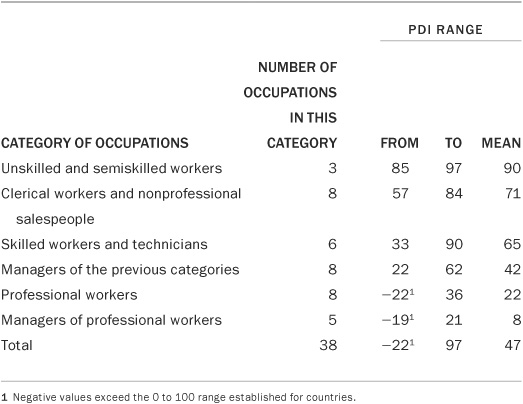

For three large countries (France, Germany, and Great Britain) in which the IBM subsidiaries contained the fullest possible range of industrial activities, PDI scores were computed for all the different occupations in the corporation, including those demanding only a lower level of education and therefore usually taken by lower- or “working”-class persons.14 Altogether, thirty-eight different occupations within these three countries could be compared.

The three questions used for calculating the PDI across countries were also correlated across occupations; it was therefore possible to compute occupational PDI values as well.15

The result of the comparison across thirty-eight occupations is summarized in Table 3.2. It demonstrates that the occupations with the lowest status and education level (unskilled and semiskilled workers) showed the highest PDI values, and those with the highest status and education level (managers of professional workers, such as engineers and scientists) produced the lowest PDI values. Between the extremes in terms of occupation, the range of PDI scores was about 100 score points—which is of the same order of magnitude as across seventy-six countries and regions (see Table 3.1; but the country differences were based on samples of people with equal jobs and equal levels of education!).

TABLE 3.2 PDI Values for Six Categories of Occupations (Based on IBM Data from Great Britain, France, and Germany)

The next question is whether the differences in power distance between occupations were equally strong within all countries. In order to test this, a comparison was done of four occupations of widely different status, from each of eleven country subsidiaries of widely different power distance levels. It turned out that the occupation differences were largest in the countries with the lowest PDI scores and were relatively small in the countries with high PDI scores.16 In other words, if the country as a whole scored larger power distance in Table 3.1, this applied to all employees, those in high-status occupations as well as those in low-status occupations. If the country scored smaller power distance, this applied most to the employees of middle or higher status: the lower-status, lower-educated employees produced power distance scores nearly as high as their colleagues in the large-PDI countries. The values of high-status employees with regard to inequality seem to depend strongly on nationality; those of low-status employees much less.17

The fact that less-educated, low-status employees in various Western countries hold more “authoritarian” values than their higher-status compatriots had already been described by sociologists. These authoritarian values not only are manifested at work but also are found in their home situations. A study in the United States and Italy in the 1960s showed that working-class parents demanded more obedience from their children than middle-class parents but that the difference was larger in the United States than in Italy.18

In the next part of this chapter, the differences in power distance scores for countries will be associated with differences in family, school, workplace, state, and ideas prevailing within the countries. Chapters 4 through 8, which deal with the other dimensions, will also be mostly structured in this way. Most of the associations described are based on the results of statistical analyses, in which the country scores have been correlated with the results of other quantitative studies, in the way described in Chapter 2. In addition, use has been made of qualitative information about families, schools, workplaces, and so on, in various countries. In this book the statistical proof will be omitted; interested readers are referred to Culture’s Consequences.

Most people in the world are born into a family. All people started acquiring their mental software immediately after birth, from the elders in whose presence they grew up, modeling themselves after the examples set by these elders.

In the large-power-distance situation, children are expected to be obedient toward their parents. Sometimes there is even an order of authority among the children themselves, with younger children being expected to yield to older children. Independent behavior on the part of a child is not encouraged. Respect for parents and other elders is considered a basic virtue; children see others showing such respect and soon acquire it themselves. There is often considerable warmth and care in the way parents and older children treat younger ones, especially those who are very young. They are looked after and are not expected to experiment for themselves. Respect for parents and older relatives lasts through adulthood: parental authority continues to play a role in a person’s life as long as the parents are alive. Parents and grandparents are treated with formal deference even after their children have actually taken control of their own lives. There is a pattern of dependence on seniors that pervades all human contacts, and the mental software that people carry contains a strong need for such dependence. When parents reach old age or if they become otherwise infirm, children are expected to support them financially and practically; grandparents often live with their children’s families.

In the small-power-distance situation, children are more or less treated as equals as soon as they are able to act, and this may already be visible in the way a baby is handled in its bath.19 The goal of parental education is to let children take control of their own affairs as soon as they can. Active experimentation by the child is encouraged; being allowed to contradict their parents, children learn to say “no” very early. Behavior toward others is not dependent on the other’s age or status; formal respect and deference are seldom shown. Family relations in such societies often strike people from other societies as lacking intensity. When children grow up, they start relating to their parents as friends, or at least as equals, and a grownup person is not apt to ask his or her parents’ permission or even advice regarding an important decision. In the ideal family, adult members are mutually independent. A need for independence is supposed to be a major component of the mental software of adults. Parents should make their own provisions for when they become old or infirm; they cannot count on their children to support them, nor can they expect to live with them.

The pictures in the two preceding paragraphs have deliberately been polarized. Reality in a given situation will most likely be in between the opposite ends of the power distance continuum: countries score somewhere along the continuum. We saw that the social class and education levels of the parents, especially in the small-power-distance countries, play an important role. Families develop their own family cultures that may be at variance with the norms of their society, and the personalities of individual parents and children can lead to nontypical behavior. Nevertheless, the two pictures indicate the ends of the line along which solutions to the human inequality dilemma in the family vary.

The Eurobarometer, a periodic survey of representative samples of the population in member countries and candidate member countries of the European Union, collected data in 2008 on the sharing of full-time and part-time work between parents in a family. In countries with larger power distances, more often both parents worked full-time; in countries with smaller power distances, more often only one of the parents worked full-time, while the other worked as well but part-time. Except in the poorest countries, these differences were independent of the countries’ national wealth. They imply a closer contact between parent and children in smaller-power-distance cultures.20

As the family is the source of our very first social mental programming, its impact is extremely strong, and programs set at this stage are difficult to change. Psychiatrists and psychoanalysts are aware of this importance of one’s family history but not always of its cultural context. Psychiatry tries to help individuals whose behavior deviates from societal norms. This book describes how the norms themselves vary from one society to another. Different norms mean that psychiatric help to a person from another society or even from a different sector of the same society is a risky affair. It demands that the helper be aware of his or her own cultural differences with and biases toward the client.21

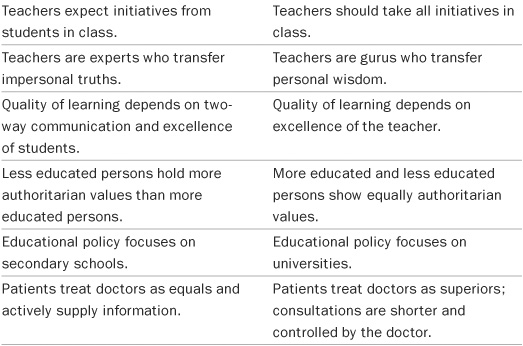

In most societies today, children go to school for at least some years. In the more affluent societies, the school period may cover more than twenty years of a young person’s life. In school the child further develops his or her mental programming. Teachers and classmates inculcate additional values, being part of a culture that honors these values. It is an unanswered question as to what extent an education system can contribute to changing a society. Can a school create values that were not yet there, or will it unwittingly only be able to reinforce what already exists in a given society? In a comparison of schools across societies, the same patterns of differences that were found within families resurge. The role pair parent-child is replaced by the role pair teacher-student, but basic values and behaviors are carried forward from one sphere into the other. And of course, most schoolchildren continue to spend most of their time within their families.

In the large-power-distance situation, the parent-child inequality is perpetuated by a teacher-student inequality that caters to the need for dependence well established in the student’s mind. Teachers are treated with respect or even fear (and older teachers even more so than younger ones); students may have to stand when they enter. The educational process is teacher centered; teachers outline the intellectual paths to be followed. In the classroom there is supposed to be a strict order, with the teacher initiating all communication. Students in class speak up only when invited to; teachers are never publicly contradicted or criticized and are treated with deference even outside school. When a child misbehaves, teachers involve the parents and expect them to help set the child straight. The educational process is highly personalized: especially in more advanced subjects at universities, what is transferred is seen not as an impersonal “truth,” but as the personal wisdom of the teacher. The teacher is a guru, a term derived from the Sanskrit word for “weighty” or “honorable,” and in India and Indonesia this is, in fact, what a teacher is called. The French term is a maître à penser, a “teacher for thinking.” In such a system the quality of one’s learning is highly dependent on the excellence of one’s teachers.

In the small-power-distance situation, teachers are supposed to treat the students as basic equals and expect to be treated as equals by the students. Younger teachers are more equal and are therefore usually more liked than older ones. The educational process is student centered, with a premium on student initiative; students are expected to find their own intellectual paths. Students make uninvited interventions in class; they are supposed to ask questions when they do not understand something. They argue with teachers, express disagreement and criticisms in front of the teachers, and show no particular respect to teachers outside school. When a child misbehaves, parents often side with the child against the teacher. The educational process is rather impersonal; what is transferred are “truths” or “facts” that exist independently of this particular teacher. Effective learning in such a system depends very much on whether the supposed two-way communication between students and teacher is, indeed, established. The entire system is based on the students’ well-developed need for independence; the quality of learning is to a considerable extent determined by the excellence of the students.

Earlier in this chapter it was shown that power distance scores are lower for occupations needing a higher education, at least in countries that as a whole score relatively low on power distance. This means that in these countries, students will become more independent from teachers as they proceed in their studies: their need for dependence decreases. In large-power-distance countries, however, students remain dependent on teachers even after reaching high education levels.

Small-power-distance countries spend a relatively larger part of their education budget on secondary schools for everybody, contributing to the development of middle strata in society. Large-power-distance countries spend relatively more on university-level education and less on secondary schools, maintaining a polarization between the elites and the uneducated.

Corporal punishment at school, at least for children of prepuberty age, is more acceptable in a large-power-distance culture than in its opposite. It accentuates and symbolizes the inequality between teacher and student and is often considered good for the development of the child’s character. In a small-power-distance society, it will readily be classified as child abuse and may be a reason for parents to complain to the police. There are exceptions, which relate to the dimension of masculinity (versus femininity) to be described in Chapter 5: in some masculine, small-power-distance cultures, such as Great Britain, corporal punishment at school is not considered objectionable by everybody.

As in the case of the family as discussed in the previous section, reality is somewhere in between these extremes. An important conditioning factor is the ability of the students: less gifted children and children with disabilities in small-power-distance situations will not develop the culturally expected sense of independence and will be handled more in the large-power-distance way. Able children from working-class families in small-power-distance societies are at a disadvantage in educational institutions such as universities that assume a small-power-distance norm: as shown in the previous section, working-class families often have a large-power-distance subculture.

Comparative studies of the functioning of health-care systems in European Union member countries have shown that, not surprisingly, the level of power distance in a society is also reflected in the relationship between doctors and patients. In countries with larger-power-distance cultures, consultations take less time, and there is less room for unexpected information exchanges.22

These differences also affect the use of medication. In countries with large-power-distance cultures, doctors more frequently prescribe antibiotics, which are seen as a quick general solution; in these countries antibiotics are also more frequently used in self-medication.23 These findings are important in view of the danger of germs’ becoming resistant to antibiotics if these treatments are used too frequently.

Another study compared blood transfusion practice across twenty-five European countries. Blood transfusion tends to be a within-nation process; there is little international trade in blood products. Countries with smaller-power-distance cultures have more blood donors, more blood collections, and more blood supplied to hospitals; in the latter two cases also, the average education level of the population plays a role. The differences are considerable: among the countries studied, the number of donors per thousand inhabitants in 2004 ranged from two to fifty-one. In all cases blood donation was an unpaid, voluntary act. Its negative correlation with PDI shows that such an act was much more likely in cultures in which people depend less on the authority of more powerful persons and are better educated. National wealth had no influence whatsoever.24

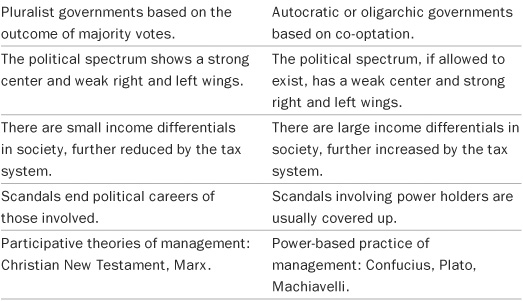

Table 3.3 summarizes the key differences between small- and large-power-distance societies discussed so far.

TABLE 3.3 Key Differences Between Small- and Large-Power-Distance Societies

I: General Norm, Family, School, and Health Care

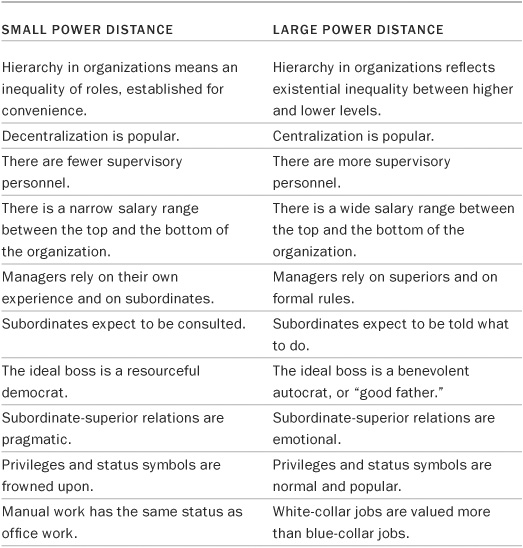

Most people start their working lives as young adults, after having gone through learning experiences in the family and at school. The role pairs parent-child, teacher-student, and doctor-patient are now complemented by the role pair boss-subordinate, and it should not surprise anybody when attitudes toward parents, especially fathers, and toward teachers, which are part of our mental programming, are transferred toward bosses.

In the large-power-distance situation, superiors and subordinates consider each other as existentially unequal; the hierarchical system is based on this existential inequality. Organizations centralize power as much as possible in a few hands. Subordinates expect to be told what to do. There is a large number of supervisory personnel, structured into tall hierarchies of people reporting to each other. Salary systems show wide gaps between top and bottom in the organization. Workers are relatively uneducated, and manual work has a much lower status than office work. Superiors are entitled to privileges (literally “private laws”), and contacts between superiors and subordinates are supposed to be initiated by the superiors only. The ideal boss in the subordinates’ eyes, the one they feel most comfortable with and whom they respect most, is a benevolent autocrat or “good father.” After some experiences with “bad fathers,” they may ideologically reject the boss’s authority completely, while complying in practice.

Relationships between subordinates and superiors in a large-power-distance organization are frequently loaded with emotions. Philippe d’Iribarne headed up a French public research center on international management. Through extensive interviews his research team compared manufacturing plants of the same French multinational in France (PDI 68), the United States (PDI 40), and the Netherlands (PDI 38). In his book on this project, d’Iribarne comments:

The often strongly emotional character of hierarchical relationships in France is intriguing. There is an extreme diversity of feelings towards superiors: they may be either adored or despised with equal intensity. This situation is not at all universal: we found it neither in the Netherlands nor in the United States.25

This quote confirms the polarization in France between dependence and counterdependence versus authority figures, which we found to be characteristic of large-power-distance countries in general.

Visible signs of status in large-power-distance countries contribute to the authority of bosses; a subordinate may well feel proud if he can tell his neighbor that his boss drives a bigger car than the neighbor’s boss. Older superiors are generally more respected than younger ones. Being a victim of power abuse by one’s boss is just bad luck; there is no assumption that there should be ways of redress in such a situation. If it gets too bad, people may join forces for a violent revolt. Packaged leadership methods invented in the United States, such as management by objectives (MBO),26 will not work, because they presuppose some form of negotiation between subordinate and superior, with which neither party will feel comfortable.

In the small-power-distance situation, subordinates and superiors consider each other as existentially equal; the hierarchical system is just an inequality of roles, established for convenience, and roles may be changed, so that someone who today is my subordinate may tomorrow be my boss. Organizations are fairly decentralized, with flat hierarchical pyramids and limited numbers of supervisory personnel. Salary ranges between top and bottom jobs are relatively small; workers are highly qualified, and high-skill manual work has a higher status than low-skill office work. According privileges to higher-ups is basically undesirable, and everyone should use the same parking lot, restrooms, and cafeteria. Superiors should be accessible to subordinates, and the ideal boss is a resourceful (and therefore respected) democrat. Subordinates expect to be consulted before a decision is made that affects their work, but they accept that the boss is the one who finally decides.

Status symbols are suspect, and subordinates will most likely comment negatively to their neighbors if their boss spends company money on an expensive car. Younger bosses are generally more appreciated than older ones. Organizations are supposed to have structured ways of dealing with employee complaints about alleged power abuse. Some packaged leadership methods, such as MBO, may work if given sufficient management attention.

Peter Smith, of the University of Sussex in the UK, through a network of colleagues, in the 1990s collected statements from more than seven thousand department managers in forty-seven countries on how they handled each of eight common work “events” (for example: “when some of the equipment or machinery in your department seems to need replacement”). For each event, eight possible sources of guidance were listed, for which the managers had to indicate to what extent they relied on each of these (for example: “formal rules and procedures”). For each of the forty-seven countries, Smith computed a verticality index, combining reliance on one’s superior and on formal rules, not on one’s own experience and not on one’s subordinates. Verticality index scores were strongly correlated with PDI: in large-power-distance countries, the managers in the sample reported relying more on their superiors and on formal rules and less on their own experience and on their subordinates.27

There is no research evidence of a systematic difference in effectiveness between organizations in large-power-distance versus small-power-distance countries. They may be good at different tasks: small-power-distance cultures at tasks demanding subordinate initiative, large-power-distance cultures at tasks demanding discipline. The important thing is for management to utilize the strengths of the local culture.

This section has again described the extremes, and most work situations will be in between and contain some elements of both large and small power distance. Management theories have rarely recognized that these different models exist and that their occurrence is culturally determined. Chapter 9 will return to this issue and show how different theories of management and organization reflect the different nationalities of their authors.

Table 3.4 summarizes key differences in the workplace between small-and large-power-distance societies.

The previous sections have looked at the implications of power distance differences among countries for the role pairs of parent-child, teacher-student, doctor-patient, and boss-subordinate; one that is obviously equally affected is authority-citizen. It must be immediately evident to anyone who follows any world news at all that in some countries power differences between authorities and citizens are not handled the same way they are in other countries. What is not so evident, but is essential for understanding, is that ways of handling power in a country tend to be rooted in the beliefs of large sectors of the population as to the proper ways for authorities to behave.

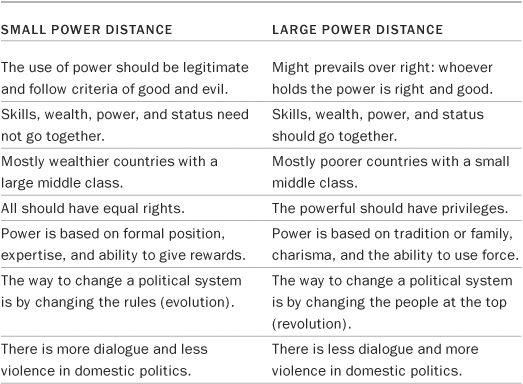

TABLE 3.4 Key Differences Between Small- and Large-Power-Distance Societies

II: The Workplace

In an analysis of data from forty-three societies, collected through the World Values Survey (see Chapter 2), U.S. political scientist Ronald Inglehart found that he could order countries on a “secular-rational versus traditional authority” dimension. Correlation analysis showed that this dimension corresponds closely to what we call power distance.28 In a society in which power distances are large, authority tends to be traditional, sometimes even rooted in religion. Power is seen as a basic fact of society that precedes the choice between good and evil. Its legitimacy is irrelevant. Might prevails over right. This is a strong statement that may rarely be presented in this form but is reflected in the behavior of those in power and of ordinary people. There is an unspoken consensus that there should be an order of inequality in this world, in which everybody has his or her place. Such an order satisfies people’s need for dependence, and it gives a sense of security both to those in power and to those lower down.

At the beginning of this chapter, reference was made to the tendency in some societies to achieve consistency in people’s positions with regard to power, wealth, and status. A desire for status consistency is typical for large-power-distance cultures. In such cultures the people who hold power are entitled to privileges and are expected to use their power to increase their wealth. Their status is enhanced by symbolic behavior that makes them look as powerful as possible. The main sources of power are one’s family and friends, charisma, and/or the ability to use force; the latter explains the frequency of military dictatorships in countries on this side of the power distance scale. Scandals involving persons in power are expected, and so is the fact that these scandals will be covered up. If something goes wrong, the blame goes to people lower down the hierarchy. If it gets too bad, the way to change the system is by replacing those in power through a revolution. Most such revolutions fail even if they succeed, because the newly powerful people, after some time, repeat the behaviors of their predecessors, in which they are supported by the prevailing values regarding inequality.

In large-power-distance countries, people read relatively few newspapers (but they express confidence in those they read), and they rarely discuss politics: political disagreements soon deteriorate into violence. The system often admits only one political party; where more parties are allowed, the same party usually always wins. The political spectrum, if it is allowed to be visible, is characterized by strong right and left wings with a weak center, a political reflection of the polarization between dependence and counterdependence described earlier. Incomes in these countries are very unequally distributed, with a few very rich people and many very poor people. Moreover, taxation protects the wealthy, so that incomes after taxes can be even more unequal than before taxes. Labor unions tend to be government controlled; where they are not, they are ideologically based and involved in politics.

Authority in small-power-distance societies was qualified by Inglehart as secular-rational: being based on practical considerations rather than on tradition. In these societies the feeling dominates that politics and religion should be separated. The use of power should be subject to laws and to the judgment between good and evil. Inequality is considered basically undesirable; although unavoidable, it should be minimized by political means. The law should guarantee that everybody, regardless of status, has equal rights. Power, wealth, and status need not go together—it is even considered a good thing if they do not. Status symbols for powerful people are suspect, and leaders may enhance their informal status by renouncing formal symbols (for example, taking the streetcar to work). Most countries in this category are relatively wealthy, with a large middle class. The main sources of power are one’s formal position, one’s assumed expertise, and one’s ability to give rewards. Scandals usually mean the end of a political career. Revolutions are unpopular; the system is changed in evolutionary ways, without necessarily deposing those in power. Newspapers are read a lot, although confidence in them is not high. Political issues are often discussed, and violence in domestic politics is rare. Countries with small-power-distance value systems usually have pluralist governments that can shift peacefully from one party or coalition to another on the basis of election results. The political spectrum in such countries shows a powerful center and weaker right and left wings. Incomes are less unequally distributed than in large-power-distance countries. Taxation serves to redistribute income, making incomes after taxes less unequal than before. Labor unions are independent and less oriented to ideology and politics than to pragmatic issues on behalf of their members.

The reader will easily recognize elements of both extremes in the history and the current practices of many countries. The European Union is based on the principles of pluralist democracy, but many member states cope with a dictatorial past. The level of power distance in their cultures helps to explain their current struggles with democracy. The Eurobarometer surveys mentioned earlier reveal, for example, that where PDI is higher, fewer people trust the police, fewer young people join a political party, and fewer people have ever participated in debates with policy makers.29 Even in the most democratic system, journalists and whistle-blowers exposing scandals have a difficult time. In less democratic systems they risk their lives.

Institutions from small-power-distance countries are sometimes copied in large-power-distance countries, because political ideas travel. Political leaders who studied in other countries may try to emulate these countries’ political systems. Governments of smaller-power-distance countries often eagerly try to export their institutional arrangements in the context of development cooperation. However, just going through the moves of an election will not change the political mores of a country if these mores are deeply rooted in the mental software of a large part of the population. In particular, underfed and uneducated masses make poor democrats, and the ways of government that are customary in more well-off countries are unlikely to function in poor ones. Actions by foreign governments intended to lead other countries toward democratic ways and respect for human rights are clearly inspired by the mental programming of the foreign helpers, and they are usually more effective in dealing with the opinions of the foreign electorate than with the problems in the countries supposed to be helped. In Chapter 11 we will come back to this dilemma and possible ways out of it.

Parents, teachers, managers, and rulers are all children of their cultures; in a way, they are the followers of their followers, and their behavior can be understood only if one also understands the mental software of their offspring, students, subordinates, and subjects. Moreover, not only the doers in this world but also the thinkers are children of a culture. The authors of management books and the founders of political ideologies generate their ideas from the background of what they learned when they were growing up. Thus, differences among countries along value dimensions such as power distance help not only in understanding differences in thinking, feeling, and behaving by the leaders and those led but also in appreciating the theories produced or adopted in these countries to explain or prescribe thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

In world history, philosophers and founders of religions have dealt explicitly with questions of power and inequality. In China around 500 B.C., Kong Ze, whose name the Jesuit missionaries two thousand years later latinized as Confucius (from the older name Kong-Fu Ze), maintained that the stability of society was based on unequal relationships between people. He distinguished the wu lun, the five basic relationships: ruler-subject, father-son, older brother–younger brother, husband-wife, and senior friend–junior friend. These relationships contain mutual and complementary obligations: for example, the junior partner owes the senior respect and obedience, while the senior partner owes the junior protection and consideration. Confucius’s ideas have survived as guidelines for proper behavior for Chinese people to this day. In the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedong tried to wipe out Confucianism, but in the meantime his own rule contained strong Confucian elements.30 Countries in the IBM study with a Chinese majority or that have undergone Chinese cultural influences are, in the order in which they appear in Table 3.1, China, Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan; they occupy the upper-medium and medium PDI zones. People in these countries accept and appreciate inequality but feel that the use of power should be moderated by a sense of obligation.

In ancient Greece around 350 B.C., Plato recognized a basic need for equality among people, but at the same time, he defended a society in which an elite class, the guardians, would exercise leadership. He tried to resolve the conflict between these diverging tendencies by playing on two meanings of the word equality, a quantitative one and a qualitative one, but to us, his arguments resemble the famous quote from George Orwell’s Animal Farm: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” Present-day Greece in Table 3.1 is found about halfway on power distance (rank 41–42, score 60).

The Christian New Testament, composed in the first centuries A.D., preaches the virtue of poverty.31 Pursuing this virtue will lead to equality in society, but its practice has been reserved to members of religious orders. It has not been popular with Christian leaders—neither of states, nor of businesses, nor of the Church itself. The Roman Catholic Church has maintained the hierarchical order of the Roman Empire; the same holds for the Eastern Orthodox churches, whereas Protestant denominations to various degrees are nonhierarchical. Traditionally Protestant nations tend to score lower on PDI than Catholic or Orthodox nations.

The Italian Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) is one of world literature’s greatest authorities on the use of political power. He distinguished two models: the model of the fox and the model of the lion. The prudent ruler, Machiavelli writes, uses both models, each at the proper time: the cunning of the fox will avoid the snares, and the strength of the lion will scare the wolves.32 Relating Machiavelli’s thoughts to national power distance differences, one finds small-power-distance countries to be accustomed to the fox model and large-power-distance countries to the lion model. Italy, in the twentieth-century IBM research data, scores in the middle zone on power distance (rank 51, score 50). It is likely that, were one to study Italy by region, the North will be more foxy and the South more lionlike. What Machiavelli did not write but what the association between political systems and citizens’ mental software suggests is that which animal the ruler should impersonate depends strongly on what animals the followers are.

Karl Marx (1818–83) also dealt with power, but he wanted to give it to people who were powerless; he never really dealt with the question of whether the revolution he preached would actually create a new powerless class. In fact, he seemed to assume that the exercise of power can be transferred from persons to a system, a philosophy in which we can recognize the mental software of the small-power-distance societies to which Marx’s mother country, Germany, today belongs. It was a tragedy for the modern world that Marx’s ideas have been mainly exported to countries at the large-power-distance side of the continuum, in which, as was argued earlier in this chapter, the assumption that power should yield to law is absent. This absence of a check to power has enabled government systems claiming Marx’s inheritance to survive even where these systems would make Marx himself turn in his grave. In Marx’s concept of the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” the dictatorship has appealed to rulers in some large-power-distance countries, but the proletariat has been forgotten. In fact, the concept is naive: in view of what we know of the human tendency toward inequality, a dictatorship by a proletariat is a logical contradiction.

The exportation of ideas to people in other countries without regard for the values context in which these ideas were developed—and the importation of such ideas by gullible believers in those other countries—is not limited to politics; it can also be observed in the domains of education and, in particular, management and organization. The economic success of the United States in the decades before and after World War II has made people in other countries believe that U.S. ideas about management must be superior and therefore should be copied. They forgot to ask about the kind of society in which these ideas were developed and applied—if they were really applied as the books claimed. Since the late 1960s the same has happened with Japanese ideas.

The United States in Table 3.1 scores on the low side, but not extremely low, on power distance (rank 57–59 out of 74). U.S. leadership theories tend to be based on subordinates with medium-level dependence needs: not too high, not too low. A key idea is participative management—that is, a situation in which subordinates are involved by managers in decisions at the discretion and initiative of these managers. Comparing U.S. theories of leadership with “industrial democracy” experiments in countries such as Sweden and Denmark (which scored extremely low on PDI), one finds that in these Scandinavian countries initiatives to participate are often taken by the subordinates, something U.S. managers find difficult to digest, because it represents an infringement on their “management prerogatives.” Management prerogatives, however, are less sacred in Scandinavia. On the other hand, U.S. theories of participative management are also unlikely to apply in countries higher on the power distance scale. Subordinates accustomed to larger Power Distances may feel embarrassed when the boss steps out of his or her role by asking their opinion, or they may even lose respect for such an ignorant superior.33

Table 3.5 summarizes key differences between small- and large-power-distance societies from the last two sections; together with Tables 3.3 and 3.4, it provides an overview of the essence of power distance differences across all spheres of life discussed in this chapter.

European countries in which the native language is Romance (French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish) scored medium to high on the power distance scale (in Table 3.1. from 50 for Italy to 90 for Romania). European countries in which the native language is Germanic (Danish, Dutch, English, German, Norwegian, Swedish) scored low (from 11 in Austria to 40 in Luxembourg). There seems to be a relationship between language area and present-day mental software regarding power distance. The fact that a country belongs to a language area is rooted in history: Romance languages all derive from Low Latin and were adopted in countries once part of the Roman Empire, or, in the case of Latin America, in countries colonized by Spain and Portugal, which themselves were former colonies of Rome. Germanic languages are spoken in countries that remained “barbaric” in Roman days, in areas once under Roman rule but reconquered by barbarians (such as England), and in former colonies of these entities. Thus, some roots of the mental program called power distance go back at least to Roman times—two thousand years ago. Countries with a Chinese (Confucian) cultural inheritance also cluster on the medium to high side of the power distance scale—and they carry a culture at least four thousand years old.

TABLE 3.5 Key Differences Between Small- and Large-Power-Distance Societies

III: The State and Ideas

None of us was present when culture patterns started to diverge between peoples: the attribution of causes for these differences is a matter of educated speculation on the basis of historical and prehistorical sources. Both the Roman and the Chinese Empires were ruled from a single power center, which presupposes a population prepared to take orders from the center. The Germanic part of Europe, on the other hand, was divided into small tribal groups under local lords who were not inclined to accept directives from anybody else. It seems a reasonable assumption that early state-hood experiences helped to develop in these peoples the common mental programs necessary for the survival of their political and social systems.

The question remains, of course, as to why these early statehood experiences deviated. One way of supporting the guesswork for causes is to look for quantitative data about countries that might be correlated with the power distance scores. A number of such quantitative variables were available. Stepwise regression, described in Chapter 2, allowed us to select from these variables the ones that successively contributed most to explaining the differences in PDI scores in Table 3.1. The result is that a country’s PDI score can be fairly accurately predicted from the following:

The country’s geographic latitude (higher latitudes associated with lower PDI)

The country’s geographic latitude (higher latitudes associated with lower PDI)

Its population size (larger size associated with higher PDI)

Its population size (larger size associated with higher PDI)

Its wealth (richer countries associated with lower PDI)34

Its wealth (richer countries associated with lower PDI)34

Geographic latitude (the distance from the equator of a country’s capital city) alone allows us to predict 43 percent of the differences (the variance) in PDI values among the fifty countries in the original IBM set. Latitude and population size together predicted 51 percent of the variance; and latitude, population size, plus national wealth (per capita gross national income in 1970, the middle year of the survey period), predicted 58 percent. If one knew nothing about these countries other than those three hard to fairly hard areas of data, one would be able to compile a list of predicted PDI scores resembling Table 3.1 pretty closely. On average, the predicted values deviate 11 scale points from those found in the IBM surveys.

Statistical relationships do not indicate the direction of causality: they do not tell which is cause and which is effect or whether the related elements may both be the effects of a common third cause. However, in the unique case of a country’s geographic position, it is difficult to consider this factor as anything other than a cause, unless we assume that in prehistoric times peoples migrated to climates that fit their concepts of power distance, which is rather far-fetched.

The logic of the relationship, supported by various research studies,35 could be about as follows: First of all, the societies involved have all developed to the level of sedentary agriculture and urban industry. The more primitive hunter-gatherer societies, for which a different logic may apply, are not included. At lower latitudes (that is, more tropical climates), agricultural societies generally meet a more abundant nature. Survival and population growth in these climates demand a relatively limited intervention of humans with nature: everything grows. In this situation the major threat to a society is the competition of other human groups for the same territory and resources. The better chances for survival exist for the societies that have organized themselves hierarchically and in dependence on one central authority that keeps order and balance.

At higher latitudes (that is, moderate and colder climates), nature is less abundant. There is more of a need for people’s intervention with nature in order to carve out an existence. These conditions support the creation of industry next to agriculture. Nature, rather than other humans, is the first enemy to be resisted. Societies in which people have learned to fend for themselves without being too dependent on more powerful others have a better chance of survival under these circumstances than societies that educate their children toward obedience.

The combination of climate and affluence is the subject of a highly interesting study by Dutch social psychologist Evert van de Vliert, to which we will refer again in Chapter 12. Van de Vliert studied the effect of climate on culture, opposing survival (high PDI) cultures to self-expression (low PDI) cultures. He proves that demanding cold or hot climates have led to survival cultures, except in affluent societies that have the means to cope with heat and cold, where we find self-expression cultures. In temperate climates, the role of affluence is less pronounced.36

National wealth in itself stands for a lot of other factors, each of which could be both an effect and a cause of smaller power distances. Here we are dealing with phenomena for which causality is almost always spiral, such as the causality of the chicken and the egg. Factors associated with more national wealth and less dependence on powerful others are as follows:

Less traditional agriculture

Less traditional agriculture

More modern technology

More modern technology

More urban living

More urban living

More social mobility

More social mobility

A better educational system

A better educational system

A larger middle class

A larger middle class

More former colonies than former colonizing nations show large power distances, but having been either a colony or a colonizer at some time during the past two centuries is also strongly related to current wealth. The data do not allow establishing a one-way causal path among the three factors of poverty, colonization, and large power differences. Assumptions about causality in this respect usually depend on what one likes to prove.

Size of population, the second predictor of power distance, fosters dependence on authority because people in a populous country will have to accept a political power that is more distant and less accessible than people from a small nation. On the other hand, a case can be made for a reversal of causality here because less dependently minded peoples will fight harder to avoid being integrated into a larger nation.

So far, the picture of differences among countries with regard to power distance has been static. The previous section claimed that some of the differences have historical roots of four thousand years or more. So much for the past, but what about the future? We live in an era of unprecedented intensification of international communication: shouldn’t this achievement eradicate the differences and help us to grow toward a world standard? And if so, will this be one of large, small, or medium power distances?

Impressionistically at least, it seems that dependence on the power of others in a large part of our world has been reduced over the past few generations. Many of us feel less dependent than we assume our parents and grandparents to have been. Moreover, independence is a politically attractive topic. Liberation and emancipation movements abound. Educational opportunities have been improved in many countries, and we have seen that power distance scores within countries decrease with increased education level. This does not mean, however, that the differences among countries described in this chapter should necessarily have changed. Countries can all have moved to lower power distance levels without changes in their mutual ranking as shown in Table 3.1.

One may try to develop a prediction about longer-term changes in power distance by looking at the underlying forces identified in the previous section. Of the factors shown to be most closely associated with power distance (latitude, size, and wealth), the first is immutable. As to the second, size of population, one could argue that in a globalizing world small and even large countries will be less and less able to make decisions at their own level and all will be more and more dependent on decisions made internationally. This development should lead to a global increase in power distances.

The third factor, wealth, increases for some countries but not for others. Increases in wealth may reduce power distances, but only if and where they benefit an entire population. Since the last decade of the twentieth century, income distribution in some wealthy countries, led by the United States, has become more and more uneven: wealth increases have benefited disproportionally those who were very wealthy already. This has the opposite effect: it increases inequality in society, not only in economic terms but also in legal terms, as the superrich can lobby with legislators and pay lawyers who earn a multiple of the salaries of judges. This kind of wealth increase, therefore, also increases power distances. In countries in which the economy stagnates or deteriorates (that is, mainly in countries that are already poor), no reduction or even a further increase in power distance is to be expected anyway.

Nobody, as far as we know, has offered evidence of a convergence of countries toward smaller differences in power distance.37 We believe that the picture of national variety presented in this chapter, with its very old historical roots, is likely to survive at least for some centuries. A worldwide homogenization of mental programs about power and dependence, independence, and interdependence under the influence of a presumed cultural melting-pot process is still very far away, if it will ever happen.

In December 1988 the following news item appeared in the press:

Stockholm, December 23. The Swedish King Carl Gustav this week experienced considerable delay while shopping for Christmas presents for his children, when he wanted to pay by check but could not show his check card. The salesperson refused to accept the check without identification. Only when helpful bystanders dug in their pockets for one-crown pieces showing the face of the king to prove his identity did the salesperson decide to accept the check, not, however, without testing the check thoroughly for authenticity and noting name and address of the holder.38

This Bernadotte (a direct descendant of the French general) still met with the same equality norm as his ancestor. How much time will have to pass before the citizens of the United States, Russia, or Zimbabwe will treat their presidents in this way? Or before Swedes start to venerate their king in the same way as the Thai do theirs?