The English Elchi [ambassador] had reached Tehran a few days before we arrived there, and his reception was as brilliant as it was possible for a dog of an unbeliever to expect from our blessed Prophet’s own lieutenant. . . . The princes and noblemen were enjoined to send the ambassador presents, and a general command issued that he and his suite were the Shah’s guests, and that, on the pain of the royal anger, nothing but what was agreeable should be said to them.

All these attentions, one might suppose, would be more than sufficient to make infidels contented with their lot; but, on the contrary, when the subject of etiquette came to be discussed, interminable difficulties seemed to arise. The Elchi was the most intractable of mortals. First, on the subject of sitting. On the day of his audience of the Shah, he would not sit on the ground, but insisted upon having a chair; then the chair was to be placed so far, and no farther, from the throne. In the second place, of shoes, he insisted upon keeping on his shoes, and not walking barefooted upon the pavement; and he would not even put on our red cloth stockings. Thirdly, with respect to hats: he announced his intention of pulling his off to make his bow to the king, although we assured him that it was an act of great indecorum to uncover the head. And then, on the article of dress, a most violent dispute arose: at first, it was intimated that proper dresses should be sent to him and his suite, which would cover their persons (now too indecently exposed) so effectually that they might be fit to be seen by the king; but this proposal he rejected with derision. He said that he would appear before the Shah of Persia in the same dress he wore when before his own sovereign.

—James Morier, The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan, 1824, Chapter LXXVII

James J. Morier (1780–1849) was a European, and The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan is a work of fiction. Morier, however, knew what he wrote about. He was born and raised in Ottoman Turkey as a son of the British consul at Constantinople (now Istanbul). Later on he spent altogether seven years as a British diplomat in Persia (present-day Iran). When Hajji Baba was translated into Persian, the readers refused to believe that it had been written by a foreigner. “Morier was by temperament an ideal traveler, reveling in the surprising interests of strange lands and peoples, and gifted with a humorous sympathy that enabled him to appreciate the motives actuating persons entirely dissimilar to himself,” to quote the editor of the 1923 version of his book.1 Morier obviously read and spoke Turkish and Persian. For all practical purposes he had become multicultural.

Human history is composed of wars between cultural groups. Joseph Campbell (1904–87), an American author on comparative mythology, found the primitive myths of nonliterate peoples without exception affirming and glorifying war. In the Old Testament, a holy book of both Judaism and Christianity and a source document for the Muslim Koran, there are numerous quotes like the following:

But in the cities of these people that the Lord your God gives you for an inheritance, you shall save alive nothing that breathes, but you shall utterly destroy them, the Hittites and the Amorites, the Canaanites and the Perizzites, the Hivites and the Jebusites, as the Lord your God has commanded.

—Deuteronomy 20:16–18

This is a religiously sanctified call for genocide.2 The fifth commandment, “Thou shalt not kill,” from the same Old Testament obviously applies only to members of the moral circle. Territorial expansion of one’s own tribe by killing off others is not only permitted but also supposed to be ordered by God. Not only in the land of the Old Testament but also in many other parts of the world, territorial conflicts involving the killing or expelling of other groups continue to this day. The Arabic name of the modern Palestinians who dispute with the Israelis the rights on the land of Israel is Philistines, the same name by which their ancestors are described in the Old Testament.

Territorial expansion is not the only casus belli (literally, “reason for war”). Human groups have found many other excuses for collectively attacking others. The threat of an external enemy has always been one of the most effective ways to maintain internal cohesion. In Chapter 6 it was shown that a basic belief in many cultures is “What is different is dangerous.” Racism assumes the innate superiority of one group over another and uses this assumption to justify resorting to violence for the purpose of maintaining this superiority. Totalitarian ideologies like apartheid imposed definitions of which groups were better and which were inferior—definitions that might be changed from one day to another. Culture pessimists wonder whether human societies can exist without enemies.

Europe, except in parts of the former Yugoslavia, seems to have reached a stage in its development in which countries that within human memory still fought each other have now voluntarily joined a supranational union. Africa, on the other hand, has become the scene of large-scale war and genocide that some have compared to the World Wars of its former colonizers.3 A functioning supranational African union still seems far away.

While cultural processes have a lot to do with issues of war and peace, war and peace will not be a main issue in this chapter. Wars represent “intended conflict” between human groups, an issue too broad for this book. The purpose of the present chapter is to look at the unintended conflicts that often arise during intercultural encounters and that happen although nobody wants them and all suffer from them. They have at times contributed to the outbreak of wars. However, it would be naive to assume that all wars could be avoided by developing intercultural communication skills.

Owing to advances in travel and communication technology, intercultural encounters in the modern world have multiplied at a prodigious rate. Today embarrassments like those between Morier’s English Elchi and the courtiers of the shah occur between ordinary tourists and locals, between schoolteachers and the immigrant parents of their students, and between businesspeople trying to set up international ventures. Subtler misunderstandings than those pictured by Morier but with similar roots still play a prominent role in negotiations between modern diplomats and/or political leaders. Intercultural communication skills can contribute to the success of negotiations, on the results of which depend the solutions to crucial global problems. Avoiding unintended cultural conflicts will be the overall theme of this chapter.

Intercultural encounters are often accompanied by similar psychological and social processes. The simplest form of intercultural encounter is between one foreign individual and a new cultural environment.

The foreigner usually experiences some form of culture shock. As illustrated over and over again in earlier chapters, our mental software contains basic values. These values were acquired early in our lives, and they have become so natural as to be unconscious. They form the basis of our conscious and more superficial manifestations of culture: rituals, heroes, and symbols (see Figure 1.2). The inexperienced foreigner can make an effort to learn some of the symbols and rituals of the new environment (words to use, how to greet people, when to bestow presents), but it is unlikely that he or she can recognize, let alone feel, the underlying values. In a way, the visitor in a foreign culture returns to the mental state of an infant, in which the simplest things must be learned over again. This experience usually leads to feelings of distress, of helplessness, and of hostility toward the new environment. Often one’s physical functioning is affected. Expatriates and migrants have more need for medical help shortly after their displacement than before or later.4

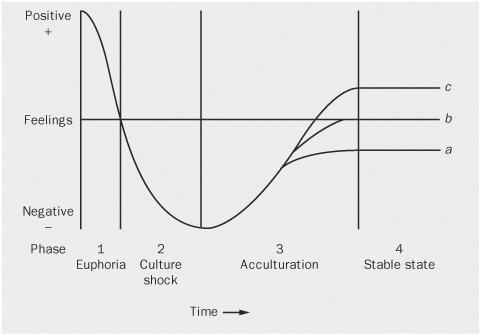

People residing in a foreign cultural environment have reported shifts of feelings over time that follow more or less the acculturation curve pictured in Figure 11.1. Feelings (positive or negative) are plotted on the vertical axis, and time is plotted on the horizontal axis. Phase 1 is a (usually short) period of euphoria: the honeymoon, the excitement of traveling and of seeing new lands. Phase 2 is the period of culture shock when real life starts in the new environment, as described earlier. Phase 3, acculturation, sets in when the visitor has slowly learned to function under the new conditions, has adopted some of the local values, finds increased self-confidence, and becomes integrated into a new social network. Phase 4 is the stable state of mind eventually reached. It may remain negative compared with home (4a)—for example, if the visitor continues to feel alienated and discriminated against. It may be just as good as before (4b), in which case the visitor can be considered to be biculturally adapted, or it may even be better (4c). In the last case the visitor has “gone native”—becoming more Roman than the Romans.

FIGURE 11.1 The Acculturation Curve

The length of the time scale in Figure 11.1 is variable; it seems to adapt to the length of the expatriation period. People on short assignments of up to three months have reported euphoria, culture shock, and acculturation phases within this period, perhaps bolstered by the expectation of being able to go home soon; people on long assignments of several years have reported culture shock phases of a year or more before acculturation set in.

Culture shocks and the corresponding physical symptoms may be so severe that assignments have to be terminated prematurely. Most international business companies have experiences of this kind with some of their expatriates. There have been cases of expatriate employees’ suicides. Culture shock problems of accompanying spouses, more often than those of the expatriated employees themselves, seem to be the reason for early return. The expatriate, after all, has the work environment that offers a cultural continuity with home. There is the story of an American wife, assigned with her husband to Nice, France, a tourist’s heaven, who locked herself up inside their apartment and never dared to go out.

Articles in the management literature often cite high premature return rates for expatriates. Dutch-Australian researcher Anne-Wil Harzing critically reviewed more than thirty articles on the subject and found statements such as this: “Empirical studies over a considerable period suggest that expatriate failure is a significant and persistent problem with rates ranging between 25 and 40 percent in the developed countries and as high as 70 percent in the case of developing countries.” Trying to check the sources of these figures, Harzing discovered very little evidence. The only reliable multicountry, multinationality study was by Professor Rosalie Tung, from Canada, who had shown that in the late 1970s, before intercultural training became really common, mean levels of premature recall of expatriates for Japanese and European companies were under 10 percent; for U.S. companies the mean was somewhere in the lower teens, with exceptional companies reporting recall rates at the 20 to 40 percent level. And this situation probably improved in the years afterward, if we assume that human resources managers worked on solving their problems. The message of dramatically high expatriate failure rates sounds good to intercultural consultants trying to sell expatriate training and to convince themselves and others of the importance of their work, but it is a myth.5 A better sales argument for the trainers is that premature return may be low but that it doesn’t really measure the problem of expatriation: the damage caused by an incompetent or insensitive expatriate who stays is much more significant.

Among refugees and migrants there is a percentage who fall seriously physically or mentally ill, commit suicide, or remain so homesick that they return, especially within the first year.

Expatriates and migrants who successfully complete their acculturation process and then return home will experience a reverse culture shock in readjusting to their old cultural environment. Migrants who have returned home sometimes find that they do not fit anymore and emigrate again, this time for good. Expatriates who successively move to new foreign environments report that the culture shock process starts all over again. Evidently, culture shocks are environment-specific. For every new cultural environment there is a new shock.

There are also standard types of reactions within host environments exposed to foreign visitors. The people in the host culture receiving a foreign culture visitor usually go through another psychological reaction cycle. The first phase is curiosity—somewhat like the euphoria on the side of the visitor. If the visitor stays and tries to function in the host culture, a second phase sets in: ethnocentrism. The hosts will evaluate the visitor by the standards of their culture, and this evaluation tends to be unfavorable. The visitor will show bad manners, as with the English Elchi; he or she will appear rude, naive, and/or stupid. Ethnocentrism is to a people what egocentrism is to an individual: considering one’s own little world to be the center of the universe. If foreign visitors arrive only rarely, the hosts will probably stick to their ethnocentrism. If regularly exposed to foreign visitors, the hosts may move into a third phase: polycentrism, the recognition that different kinds of people should be measured by different standards. Some will develop the ability to understand foreigners according to these foreigners’ own standards. This is the beginning of bi-or multiculturality.6

As we saw in Chapter 6, cultures that are uncertainty avoiding will resist polycentrism more than cultures that are uncertainty accepting. However, individuals within a culture vary around the cultural average, so in intolerant cultures one may meet tolerant hosts, and vice versa. The tendency to apply different standards to different kinds of people may also turn into xenophilia, the belief that in the foreigner’s culture, everything is better. Some foreigners will be pleased to confirm this belief. There is a tendency among expatriates to idealize what one remembers from home. Neither ethnocentrism nor xenophilia is a healthy basis for intercultural cooperation, of course.

Intercultural encounters among groups rather than with single foreign visitors provoke group feelings. Contrary to popular belief, intercultural contact among groups does not automatically breed mutual understanding. It usually confirms each group in its own identity. Members of the other group are perceived not as individuals but rather in a stereotyped fashion: all Chinese look alike; all Scots are stingy. As compared with the heterostereotypes about members of the other group, autostereotypes are fostered about members of one’s own group. Such stereotypes will even affect the perception of actual events: if a member of one’s own group attacks a member of the other group, one may be convinced (“I saw it with my own eyes”) that it was the other way around.

As we saw in Chapter 4, the majority of people in the world live in collectivist societies, in which, throughout their lives, people remain members of tight in-groups that provide them with protection in exchange for loyalty. In such a society, groups with different cultural backgrounds are out-groups to an even greater extent than out-groups from their own culture. Integration across cultural dividing lines in collectivist societies is even more difficult to obtain than in individualist societies. This is the major problem of many decolonized nations, such as those of Africa in which national borders inherited from the colonial period in no way respect ethnic and cultural dividing lines.

Establishing true integration among members of culturally different groups requires environments in which these people can meet and mix as equals. Sports clubs, universities, work organizations, and armies can assume this role. Some ethnic group cultures produce people with specific skills, such as sailors or traders, and such skills can become the basis for their integration in a larger society.

In most intercultural encounters the parties also speak different native languages. Throughout history this problem has been resolved by the use of trade languages such as Malay, Swahili or, more and more, derivations from English. Trade languages are pidgin forms of original languages, and the trade language of the modern world can be considered a form of business pidgin English. Language differences contribute to cultural misperceptions. In an international training program within IBM, trainers used to rate participants’ future career potential. A follow-up study of actual careers during a period of up to eight years afterward showed that the trainers had consistently overestimated participants whose native language was English (the course language) and underestimated those whose languages were French or Italian, with native German speakers taking a middle position.7

Communication in trade languages or pidgin limits exchanges to the issues for which these simplified languages have words. To establish a more fundamental intercultural understanding, the foreign partner must acquire the host culture language. Having to express oneself in another language means learning to adopt someone else’s frame of reference. It is doubtful whether one can be bicultural without also being bilingual.8 Although the words of which a language consists are symbols in terms of the onion diagram (Figure 1.2), which means that they belong to the surface level of a culture, they are also the vehicles of culture transfer. Moreover, words are obstinate vehicles: our thinking is affected by the categories for which words are available in our language.9 Many words have migrated from their language of origin into others because they express something unique: algebra, management, computer, apartheid, machismo, perestroika, geisha, sauna, weltanschauung, weltschmerz, karaoke, mafia, savoir vivre.

The skill of expressing oneself in more than one language is unevenly distributed across countries. People from smaller, affluent countries, such as the Swiss, Belgians, Scandinavians, Singaporeans, and Dutch, benefit from both frequent contact with foreigners and good educational systems, and therefore they tend to be polyglot. Their organizations possess a strategic advantage in intercultural contacts in that they nearly always have people available who speak several foreign languages, and whoever speaks more than one language will more easily pick up additional ones.

Paradoxically, having English, the world trade language, as one’s native tongue is a liability, not an asset, for truly communicating with other cultures. Native English speakers do not always realize this. They are like the proverbial American farmer from Kansas who is alleged to have said, “If English was good enough for Jesus Christ, it is good enough for me.”10 Geert once met an Englishman working near the Welsh border who said he turned down an offer of a beautiful home across the border, in Wales, because there his young son would have had to learn Welsh as a second language at school. In our view, he missed a unique contribution to his son’s education as a world citizen.

Language and culture are not so closely linked that sharing a language implies sharing a culture, nor should a difference in language always impose a difference in cultural values. In Belgium, where Dutch and French are the two dominant national languages (there is a small German-speaking area too), the scores of the Dutch-speaking and French-speaking regions on the four dimensions of the IBM studies were fairly similar, and both regions scored rather like France and different from the Netherlands. This finding reflects Belgian history: the middle and upper classes used to speak French, whatever the language of their ancestors, and tended to adopt the French culture; the lower classes in the Flemish part spoke Dutch, whatever the language of their ancestors, but when they moved up in status, they conformed to the culture of the middle classes. The IBM studies included a similar comparison between the German-and French-speaking regions of Switzerland. In this case the picture was different: the German-speaking part scored similar to Germany, and the French-speaking part scored similar to France. Switzerland’s historical development was different from Belgium’s: in Switzerland the language distribution followed the cantons (independent provinces) rather than the social class structure. This also helps to explain why language is a hot political issue in Belgium but not in Switzerland.11

Without knowing the language, one will miss a lot of the subtleties of a culture and be forced to remain a relative outsider. One of these subtleties is humor. What is considered funny is highly culture-specific. Many Europeans are convinced that Germans have no sense of humor, but this simply means they have a different sense of humor. In intercultural encounters the experienced traveler knows that jokes and irony are taboo until one is absolutely sure of the other culture’s conception of what represents humor.

Raden Mas Hadjiwibowo, the Indonesian business executive whose description of Javanese family visits was quoted in Chapter 4, has written an insightful analysis of the difference between the Indonesian and the Dutch senses of humor. One of his case studies runs as follows:

It was an ordinary morning with a routine informal office meeting. They all sat around the meeting table, and found themselves short of one chair. Markus, one of the Indonesian managers, looked in the connecting office next door for a spare chair.

The next door office belonged to a Dutch manager, Frans. He was out, but he would not mind lending a chair; all furniture belonged to the firm anyway. Markus was just moving one of Frans’s chairs through the connecting door when Frans came in from the other side.

Frans was in a cheerful mood. He walked over to his desk to pick up some papers, and prepared for leaving the room again. In the process he threw Markus a friendly grin and as an afterthought he called over his shoulder: “You’re on a nice stealing spree, Markus?” Then he left, awaiting no answer.

When Frans returned to his office after lunch, Markus was waiting for him. Frans noticed Markus had put on a tie, which was unusual. “Markus, my good friend, what can I do for you?” Frans asked. Markus watched him gloomily, sat straight in his chair and said firmly and solemnly: “Frans, I hereby declare that I am not a thief.”

Dumbfounded, Frans asked what the hell he was talking about. It took them another forty-five minutes to resolve the misunderstanding.12

In the Dutch culture, in which the maintenance of face and status is not a big issue, the “friendly insult” is a common way of joking among friends. “You scoundrel” or “you fool,” if pronounced with the right intonation, expresses warm sympathy. In Indonesia, where status is sacred and maintaining face is imperative, an insult is always taken literally. Frans should have known this.

Popular media often suggest that communication technologies, including television, e-mail, the Internet, mobile telephones, and social software, will bring people around the world together in a global village where cultural differences cease to matter. This dominance of technology over culture is an illusion. The software of the machines may be globalized, but the software of the minds that use them is not.

Electronic communication enormously increases the amount of information accessible to its users, but it does not increase their capacity to absorb this information, nor does it change their value systems. As users, we select information according to our values. Following the model of our parents, we read newspapers and watch TV programs that we expect to present our preferred points of view, and confronted with the almost unlimited offer of electronic information, we again pick whatever reinforces our preexisting ideas. The experience with the Internet has shown that people use it to do mostly things they would have done anyway, only maybe now they do these things more and faster.

Communication technologies increase our consciousness of differences between and within countries. Some disadvantaged groups, watching TV programs showing how people live elsewhere in the world, will want their share of the world’s wealth. Some privileged groups, informed about suffering and strife elsewhere, will want to close their borders. Many authoritarian governments actively block foreign sources of information. Even Google, supposed champion of free information, has closed down access to certain sites in certain countries depending on local taboos.

In summary, communication technologies will not by themselves reduce the need for intercultural understanding. The Internet, in particular, makes it easy for extremist groups to create their own moral circle, removed from mainstream society and often exceedingly hostile toward it. On the other hand, when wisely used, communication technologies may be among the tools for intercultural learning.

Tourism represents the most superficial form of intercultural encounter. Tourists traveling in mass may spend two weeks in Morocco, Bali, or Cancun without gleaning anything about the local culture at all. Personnel in the host country who work in the tourism industry will learn something about the culture of the tourists, but their picture of the way the tourists live at home will be highly distorted. What one group picks up from the other group is on the level of symbols (see Figure 1.2): words, fashion articles, music, and the like.

The economic effects of mass tourism on the host countries may or may not be favorable. Traditional sources of income are often destroyed, and the revenues of tourism go to governments and foreign investors, with the consequence that the local population may suffer more than it benefits. The environmental effects can be disastrous. Tourism is, from many points of view, a mixed blessing.

Tourism can nevertheless be the starting point for more fundamental intercultural encounters. It breaks the isolation of cultural groups and creates an awareness that there exist other people who have other ways. The seeds planted in some minds may take root later. Some tourists start learning the language and history of the country they have visited and to which they want to return. Hosts start learning the tourists’ languages to promote their businesses. Personal friendships develop between the most unlikely people in the most unlikely ways. On the basis of intercultural encounters, the possibilities of tourism probably outweigh the disadvantages.

An American teacher at a foreign-language institute in Beijing exclaimed in class, “You lovely girls, I love you.” Her students, according to a Chinese observer, were terrified. An Italian professor teaching in the United States complained bitterly about the fact that students were asked to formally evaluate his course. He did not think that students should be the judges of the quality of a professor. An Indian lecturer at an African university had a student who arrived six weeks late for the curriculum, but he had to admit him because he was from the same village as the dean. Intercultural encounters in schools can lead to much perplexity.13

Most intercultural encounters in schools are of one of two types: between local teachers and foreign, migrant, or refugee students or between expatriate teachers, hired as foreign experts or sent as missionaries, and local students. Different value patterns in the cultures from which the teacher and the student have come are one source of problems. Chapters 3 through 7 described consequences for the school situation of differences in values related to power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, and long-or short-term orientation. These differences often affect the relationships between teacher and students, among students, and between teacher and parents.

Because language is the vehicle of teaching, what was mentioned earlier about the role of language in intercultural encounters applies in its entirety to the teaching situation. The chances for successful cultural adaptation are better if the teacher teaches in the students’ language than if the student has to learn in the teacher’s language, because the teacher has more power over the learning situation than any single student.

The course language affects the learning process. At INSEAD international business school, in France, Geert taught the same executive course in French to one group and in English to another; both groups were composed of people from several nationalities. Discussing a case study in French led to highly stimulating intellectual discussions but few practical conclusions. When the same case was discussed in English, it would not be long before someone asked, “So what?” and the class tried to become pragmatic. Both groups used the same readings, partly from French authors translated into English, partly vice versa. Both groups liked the readings originally written in the class language and condemned the translated ones as “unnecessarily verbose, with a rather meager message which could have been expressed on one or two pages.” The comments of the French-language class on the readings translated from English therefore were identical to the comments of the English-language class on the readings translated from French. What is felt to be a message in one language does not necessarily survive the translation process. Information is more than words: it is words that fit into a cultural framework. Culturally adequate translation is an undervalued art.

Beyond differences in language, students and teachers in intercultural encounters run into differences in cognitive abilities. “Our African engineers do not think like engineers; they tend to tackle symptoms, rather than view the equipment as a system,” said a British training manager, unconscious of his own ethnocentrism. Fundamental studies by development psychologists have shown that the things we have learned are determined by the demands of the environment in which we grew up. People will become good at doing the things that are important to them and that they have occasion to do often. Being from a generation that predates the introduction of pocket calculators in schools, Geert will perform calculations in his head for which his grandchildren prefer to use a machine. Learning abilities, including the development of memory, are rooted in the total pattern of a society. In China the nature of the script (for a moderately literate person, at least three thousand complex characters)14 develops children’s ability at pattern recognition, but it also imposes a need for rote learning.

Intercultural problems arise also because expatriate teachers bring irrelevant materials with them. A Congolese friend, studying in Brussels, recalled that at primary school in Lubumbashi her teacher, a Belgian nun, made the children recite in her history lesson “Nos ancêtres, les Gaulois” (“Our ancestors, the Gauls”). During a visiting teaching assignment to China, a British lecturer repeated word for word his British organizational behavior course. Much of what students from poor countries learn at universities in wealthy countries is hardly relevant in their home country situation. What interest does a future manager in an Indian company have in mathematical modeling of the U.S. stock market? The know-how supposed to make a person succeed in an industrial country is not necessarily the same as what will help the development of a country that is currently poor.

Finally, intercultural problems can be based on institutional differences in the societies from which the teachers and students have come, differences that generate different expectations as to the educational process and the role of various parties in it. From what types of families are students and teachers recruited? Are educational systems elitist or antielitist? Visiting U.S. professors in a Latin American country may think they contribute to the economic development of the country, while in actual fact they contribute only to the continuation of elite privileges. What role do employers play in the educational system? In Switzerland and Germany, traineeships in industry or business are a respected alternative to a university education, allowing people to reach the highest positions, but this is not the case in most other countries. What role do the state and/or religious bodies play? In some countries (France, Russia) the government prescribes the curriculum in painstaking detail; in others the teachers are free to define their own. In countries in which both private and public schools exist, the private sector may be for the elites (United States) or for the dropouts (the Netherlands, Switzerland). Where does the money for the schools come from? How well are teachers paid, and what is their social status? In China teachers are traditionally highly respected but poorly paid. In Britain the status of teachers has traditionally been low; in Germany and Japan, high.

What are considered minorities in a country is a matter of definition. It depends on hard facts, including the distribution of the population, the economic situation of population groups, and the intensity of the interrelations among groups. It also depends on cultural values (especially uncertainty avoidance and collectivism, which facilitate labeling groups as outsiders) and on cultural practices (languages, felt and attributed identities, interpretations of history). These factors affect the ideology of the majority and sometimes also of the minority, as well as their level of mutual prejudice and discrimination. Minority problems are always also, and often primarily, majority problems.

Minorities in the world include a wide variety of groups, of widely varying status, from underclass to entrepreneurial and/or academic elite:

Original populations overrun by immigrants (for example, native Americans and Australian aborigines)

Original populations overrun by immigrants (for example, native Americans and Australian aborigines)

Descendants of economical, political, or ethnic migrants or refugees (now the majorities in the United States and Australia, among other countries)

Descendants of economical, political, or ethnic migrants or refugees (now the majorities in the United States and Australia, among other countries)

Descendants of imported labor (examples are American blacks, Turks, and Mediterraneans in northwestern Europe)

Descendants of imported labor (examples are American blacks, Turks, and Mediterraneans in northwestern Europe)

Natives of former colonies (for example, Indians and Pakistanis in Britain and northern Africans in France)

Natives of former colonies (for example, Indians and Pakistanis in Britain and northern Africans in France)

International nomads (Sinti and Roma people—Gypsies—in most of Europe and partly even overseas)

International nomads (Sinti and Roma people—Gypsies—in most of Europe and partly even overseas)

In many countries the minority picture is highly volatile because of ongoing migration. The number of people in the second half of the twentieth century who left their native countries and moved to a completely different environment is larger than ever before in human history. The effect in all cases is that persons and entire families are parachuted into cultural environments vastly different from the ones in which they were mentally programmed, often without any preparation. They have to learn a new language, but a much larger problem is that they have to function in a new culture. Hassan Bel Ghazi, a Moroccan immigrant to the Netherlands, wrote:

Imagine: One day you get up, you look around but you can’t believe your eyes. . . . Everything is upside down, inside as well as outside. . . . You try to put things back in their old place but alas—they are upside down forever. You take your time, you look again and then you have an idea: “I’ll put myself upside down too, just like everything else, to be able to handle things.” It doesn’t work. . . . And the world doesn’t understand why you stand right.15

Political ideologies about majority-minority relations vary immensely. Racists and ultrarightists want to close borders and expel present minorities—or worse. The policies of civilized governments aim somewhere between two poles on a continuum. One pole is assimilation, which means that minority citizens should become like everybody else and lose their distinctiveness as fast as possible. The other pole is integration, which implies that minority citizens, while accepted as full members of the host society, are at the same time encouraged to retain a link with their roots and their collective identity. Paradoxically, policies aiming at integration have led to better and faster adaptation of minorities than policies enforcing assimilation.

Migrants and refugees often came in as presumed temporary expatriates but turned out to be stayers. In nearly all cases they moved from a more traditional, collectivist society to a more individualist society. For their adaptation it is essential that they find support in a community of compatriots in the country of migration, especially if they are single, but even when they come with their families, which anyway represent a much narrower group than they were accustomed to in their home country. Maintaining migrant communities fits into an integration philosophy as previously described. Unfortunately, host country politicians, responding from their individualist value position, often fear the forming of migrant ghettos and try to disperse the foreigners, falsely assuming that this action will accelerate their adaptation.

Migrants and refugees usually also experience differences in power distance. Host societies tend to be more egalitarian than the places the migrants have left. Migrants experience this difference both negatively and positively—lack of respect for elders but better accessibility of authorities and teachers, although they tend to distrust authorities at first. Differences on masculinity-femininity, on uncertainty avoidance, and on indulgence between migrants and hosts may go either way, and the corresponding adaptation problems are specific to the pairs of cultures involved.

First-generation migrant families experience standard dilemmas. At work, in shops and public offices, and usually also at school, they interact with locals, learn some local practices, and are confronted with local values. At home, meanwhile, they try to maintain the practices, values, and relationship patterns from their country of origin. They are marginal people between two worlds, and they alternate daily between one and the other.

The effect of this marginality is different for the different generations and genders. The immigrating adults are unlikely to trade their home country values for those of the host country; at best they make small adaptations. The father tries to maintain his traditional authority in the home, but at work his status is often low. Migrants start in jobs nobody else wants. The family knows this, and he loses face toward his relatives. If he is unemployed, this makes him lose face even more. He frequently has problems with the local language, which makes him feel foolish. Sometimes the father is illiterate even in his own language. He has to seek the help of his children or of social workers in filling out forms and dealing with the authorities. He is often discriminated against by employers, police, authorities, and neighbors.

The mother in some migrant cultures is virtually a prisoner in the home, not expected to leave it when the father has gone to work. In these cases she has no contact with the host society, does not learn the language, and remains completely dependent on her husband and children. In other cases the mother has a job too. She may be the main breadwinner of the family, a severe blow to the father’s self-respect. She meets other men, and her husband may suspect her of unfaithfulness. The marriage sometimes breaks up. Yet there is no way back. As noted earlier, migrants who have returned home often find that they do not fit anymore and remigrate.

The second generation, children born in or brought early to the new country, acquires conflicting mental programs from the family side and from the local school and community side. Their values reflect partly their parents’ culture, partly their new country’s, with wide variations among individuals, groups, and host countries.16 The sons suffer most from their marginality. Some succeed miraculously well, and benefiting from the better educational opportunities, they enter skilled and professional occupations. Others, escaping parental authority at home, drop out of school and find collectivist protection in street gangs; they risk becoming a new underclass in the host society. The daughters often adapt better, although their parents worry more about them. At school they are exposed to an equality between the genders unknown in the society from which they have come. Sometimes parents hurry them into the safety of an arranged marriage with a compatriot.17

On the upside, however, many of these problems are transitional; third-generation migrants are mostly absorbed into the population of the host country, exhibiting concomitant values, and are distinguishable only by a foreign family name and maybe by specific religious and family traditions. This three-generation adaptation process has also operated in past generations; an increasing share of the population of modern societies descends partly from foreign migrants.

Whether migrant groups are thus integrated or fail to adapt and turn into permanent minorities depends as much on the majority as on the migrants themselves. Agents of the host society who interact frequently with minorities, migrants, and refugees can do a lot to facilitate their integration. They are the police, social workers, doctors, nurses, personnel officers, counter clerks in government offices, and teachers. Migrants coming from large-power-distance, collectivist cultures may distrust such authorities more than locals do, for cultural reasons. In contrast, teachers, for example, can benefit from the respect their status earns them from the parents of their migrant students. They will have to invite those parents (especially fathers) for discussion; the social distance perceived by the migrant parents is much larger than most teachers are accustomed to. Unfortunately, in any host society a share of the locals (politicians, police, journalists, teachers, neighbors) fall victim to ethnocentric and racist philosophies, compounding the migrants’ adaptation problems through primitive manifestations of uncertainty avoidance: “What is different is dangerous.”

Particular expertise is demanded from mental health professionals dealing with migrants and refugees. Ways of dealing with health concerns and disability differ considerably between collectivist and individualist societies. The high level of acculturative stress in migrants puts them at risk for mental health disorders, and methods of psychiatric treatment developed for host country patients may not work with migrants, again for cultural reasons. Most countries with a large migrant population such as Australia recognize transcultural psychiatry (and transcultural clinical psychology) as a special field. Some psychiatrists and psychologists specialize in the treatment of political refugees suffering from the aftereffects of war or torture.

Not just host country citizens can be blamed for racism and ethnocentrism; migrants themselves sometimes behave in racist and ethnocentric ways, toward other migrants and toward hosts. Living as they do in an unfamiliar and often hostile environment, the migrants can be said to have a better excuse. Some resort to religious fundamentalisms although at home they were hardly religious at all. Fundamentalism is often found among marginal groups in society, and these migrants are the new marginals.

Negotiations, whether in politics or in business and whether international or not, share some universal characteristics:

Two or more parties with (partly) conflicting interests

Two or more parties with (partly) conflicting interests

A common need for agreement because of an expected gain from such agreement

A common need for agreement because of an expected gain from such agreement

An initially undefined outcome

An initially undefined outcome

A means of communication between parties

A means of communication between parties

A control and decision-making structure on either side by which negotiators are linked to their superiors or their constituency

A control and decision-making structure on either side by which negotiators are linked to their superiors or their constituency

Books have been published on the art of negotiation; it is a popular theme for training courses. Negotiations have even been simulated on computers. However, the theories and computer models tend to use assumptions about the values and objectives of the negotiators taken from Western societies, in particular from the United States. In international negotiations, different players may hold different values and objectives.18

National cultures will affect negotiation processes in several ways:

Power distance will affect the degree of centralization of the control and decision-making structure and the importance of the status of the negotiators.

Power distance will affect the degree of centralization of the control and decision-making structure and the importance of the status of the negotiators.

Collectivism will affect the need for stable relationships between (opposing) negotiators. In a collectivist culture replacement of a person means that a new relationship will have to be built, which takes time. Mediators (go-betweens) are key in maintaining a viable pattern of relationships that allows progress.

Collectivism will affect the need for stable relationships between (opposing) negotiators. In a collectivist culture replacement of a person means that a new relationship will have to be built, which takes time. Mediators (go-betweens) are key in maintaining a viable pattern of relationships that allows progress.

Masculinity will affect the need for ego-boosting behavior and the sympathy for the strong on the part of negotiators and their superiors, as well as the tendency to resolve conflicts by a show of force. Feminine cultures are more likely to resolve conflicts by compromise and to strive for consensus.

Masculinity will affect the need for ego-boosting behavior and the sympathy for the strong on the part of negotiators and their superiors, as well as the tendency to resolve conflicts by a show of force. Feminine cultures are more likely to resolve conflicts by compromise and to strive for consensus.

Uncertainty avoidance will affect the (in)tolerance of ambiguity and (dis)trust in opponents who show unfamiliar behaviors, as well as the need for structure and ritual in the negotiation procedures.

Uncertainty avoidance will affect the (in)tolerance of ambiguity and (dis)trust in opponents who show unfamiliar behaviors, as well as the need for structure and ritual in the negotiation procedures.

Long-term orientation will affect the perseverance to achieve desired ends even at the cost of sacrifices.

Long-term orientation will affect the perseverance to achieve desired ends even at the cost of sacrifices.

Indulgence will affect the atmosphere of the negotiations and the strictness of protocols.

Indulgence will affect the atmosphere of the negotiations and the strictness of protocols.

Effective intercultural negotiations demand an insight into the range of cultural values to be expected among partners from other countries, in comparison with the negotiator’s own culturally determined values. They also demand language and communication skills to guarantee that the messages sent to the other party or parties will be understood in the way they were meant by the sender. They finally demand organization skills for planning and arranging meetings and facilities, involving mediators and interpreters, and handling external communications.

Experienced diplomats have usually acquired a professional savoir faire that enables them to negotiate successfully with other diplomats regarding issues on which they are empowered to decide themselves. The problem, however, is that in issues of real importance diplomats are usually directed by politicians who have the power but not the diplomatic savoir faire. Politicians often make statements intended for domestic use, which the diplomats are obliged to explain to foreign negotiation partners. The amount of discretion left to diplomats is in itself a cultural characteristic that varies from one society and political system to another. Modern communication possibilities contribute to limiting the discretion of diplomats; Morier’s English Elchi had a lot of discretionary power by virtue of the simple fact that communicating with England in those days took at least three months.

Notwithstanding, there is no doubt that the quality of intercultural encounters in international negotiations can contribute to avoiding unintended conflict, if the actors are of the proper hierarchical level for the decisions at stake. This is why summit conferences are so important—here are the people who do have the power to negotiate. The hitch is that they usually rose to their present position because they hold strong convictions in harmony with the national values of their country, and for this same reason they have difficulty recognizing that others function according to different mental programs. A trusted foreign minister or ambassador who has both the ear of the top leader and diplomatic sensitivity is an invaluable asset to a country.

Permanent international organizations, such as the various United Nations agencies, the European Commission, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, have developed their own organizational cultures, which affect their internal international negotiations. Even more than in the case of the diplomats’ occupational culture, these organizational cultures reside at the more superficial level of practices, common symbols, and rituals, rather than of shared values. Exceptions are “missionary” international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as the International Red Cross, Amnesty International, and Greenpeace.

Thus, the behavior of international negotiators is influenced by culture at three levels: national, occupational, and organizational.

Business negotiations differ from political negotiations in that the actors are more often amateurs in the negotiation field. Specialists can prepare negotiations, but especially if one partner is from a large-power-distance culture, persons with appropriate power and status have to be brought in for the formal agreement. International negotiations have become a special topic in business education, so it is hoped that future generations of businesspersons will be better prepared. The following discussion will argue for the need for corporate diplomats in multinationals.

If intercultural encounters are as old as humanity, multinational business is as old as organized states. Business professor Karl Moore and historian David Lewis have described four cases of multinational business in the Mediterranean area between 1900 and 100 B.C., run by Assyrians, Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans. History does not justify claims that one particular type of capitalism is inevitably and forever superior to everything else.19

The functioning of multinational business organizations hinges on intercultural communication and cooperation. Chapters 9 and 10 related shared values to national cultures and shared practices to organizational (corporate) cultures. Multinationals abroad meet alien value patterns, but their shared practices (symbols, heroes, and rituals) keep the organization together.

The basic values of a multinational business organization are determined by the nationality and personality of its founder(s) and later significant leaders. Multinationals with a dominant home culture have a clearer set of basic values and therefore are easier to run than international organizations that lack such a common frame of reference. In multinational business organizations the values and beliefs of the home culture are taken for granted and serve as a frame of reference at the head office. Persons in linchpin roles between foreign subsidiaries and the head office need to be bicultural, because they need a double trust relationship, on the one side with their home culture superiors and colleagues and on the other side with their host culture subordinates. Two roles are particularly crucial:

The country business unit manager: this person reports to an international head office.

The country business unit manager: this person reports to an international head office.

The corporate diplomat: this person is a home country or other national impregnated with the corporate culture, whose occupational background may vary but who is experienced in living and functioning in various foreign cultures. Corporate diplomats are essential to make multinational structures work, as liaison persons in international, regional, or national head offices or as temporary managers for new ventures.20

The corporate diplomat: this person is a home country or other national impregnated with the corporate culture, whose occupational background may vary but who is experienced in living and functioning in various foreign cultures. Corporate diplomats are essential to make multinational structures work, as liaison persons in international, regional, or national head offices or as temporary managers for new ventures.20

Other managers and members of foreign national subsidiaries do not have to be bicultural. Even if the foreign subsidiaries formally adopt home culture ideas and policies, they will internally function according to the value systems and beliefs of the host culture.

As mentioned before, biculturality implies bilingualism. There is a difference in coordination strategy between most U.S. and most non-U.S. multinational organizations. Most American multinationals put the burden of biculturality on the foreign nationals. It is the latter who are bi- or multilingual (most American executives in multinationals are monolingual). This goes together with a relatively short stay of American executives abroad; two to five years per foreign country is fairly typical. These executives often live in ghettos. The main tool of coordination consists of unified worldwide policies that can be maintained with a regularly changing composition of the international staff because they are highly formalized. Most non-American multinationals put the burden of biculturality on their own home country nationals. They are almost always multilingual (with the possible exception of the British, although even they are usually more skilled in other languages than the Americans). The typical period of stay in another country tends to be longer, between five and fifteen years or more, so that expatriate executives of non-American multinationals may “go native” in the host country; they mix more with the local population, enroll their children in local schools, and live less frequently in ghettos. The main tool of coordination is these expatriate home country nationals, rather than formal procedures.21

Biculturality is difficult to acquire after childhood, and the number of failures would be larger were it not that what is necessary for the proper functioning of multinational organizations is only task-related biculturality. With regard to other aspects of life—tastes, hobbies, religious feelings, and private relations—expatriate multinational executives can afford to, and usually do, remain monocultural.

Chapter 9 argued that implicit models of organizations in people’s minds depend primarily on the combination of power distance and uncertainty avoidance. Differences in power distance are more manageable than differences in uncertainty avoidance. In particular, organizations headquartered in smaller-power-distance cultures usually adapt successfully in larger-power-distance countries. Local managers in high-PDI subsidiaries can use an authoritative style even if their international bosses behave in a more participative fashion.

Chapter 3 opened with the story of the French general Bernadotte’s culture shock after he became king of Sweden. A Frenchman sent to Copenhagen by a French cosmetics company as a regional sales manager told Geert about his first day in the Copenhagen office. He called his secretary and gave her an order in the same way as he would do in Paris. But instead of saying, “Oui, Monsieur,” as he expected her to do, the Danish woman looked at him, smiled, and said, “Why do you want this to be done?”

Countries with large-power-distance cultures have rarely produced large multinationals; multinational operations demand a higher level of trust than is normal in these countries, and they do not permit the centralization of authority that managers at headquarters in these countries need in order to feel comfortable.

Differences in uncertainty avoidance represent a serious problem for the functioning of multinationals, whichever way they go. This is because if rules mean different things in different countries, it is difficult to keep the organization together. In cultures manifesting weak uncertainty avoidance such as the United States and even more in Britain and, for example, Sweden, managers and nonmanagers alike feel definitely uncomfortable with systems of rigid rules, especially if it is evident that many of these rules are never followed. In cultures with strong uncertainty avoidance such as most of the Latin world, people feel equally uncomfortable without the structure of a system of rules, even if many of these dictates are impractical and impracticable. At either pole of the uncertainty-avoidance dimension, people’s feelings are fed by deep psychological needs, related to the control of aggression and to basic security in the face of the unknown (see Chapter 6).

Organizations moving to unfamiliar cultural environments are often sorely unprepared for negative reactions of the public or the authorities to what they do or want to do. Perhaps the effect of the collective values of a society is nowhere as clear as in such cases. These values have been institutionalized partly in the form of legislation (and in the way in which legislation is applied, which may differ considerably from what is actually written in the law); in labor union structures, programs, and power positions; and in the existence of organizations of stakeholders such as consumers or environmentalists. The values are partly invisible to the newcomer, but they become all too visible in press reactions, government decisions, or organized actions by uninvited interest groups. A few inferences from the value differences exposed in Chapters 3 through 7 with regard to the reactions of the local environment are listed here:

Civic action groups are more likely to be formed in low-PDI, low-UAI cultures than elsewhere.

Civic action groups are more likely to be formed in low-PDI, low-UAI cultures than elsewhere.

Business corporations will have to be more concerned with informing the public in low-PDI, low-UAI cultures than elsewhere.

Business corporations will have to be more concerned with informing the public in low-PDI, low-UAI cultures than elsewhere.

Public sympathy and legislation on behalf of economically and socially weak members of society are more likely in low-MAS countries.

Public sympathy and legislation on behalf of economically and socially weak members of society are more likely in low-MAS countries.

Public sympathy and both government and private funding for aid to economically weak countries and for disaster relief anywhere in the world will be stronger in affluent low-MAS countries than in affluent high-MAS countries.

Public sympathy and both government and private funding for aid to economically weak countries and for disaster relief anywhere in the world will be stronger in affluent low-MAS countries than in affluent high-MAS countries.

Public sympathy and legislation on behalf of environmental conservation and maintaining the quality of life are more likely in low-PDI, low-MAS countries.

Public sympathy and legislation on behalf of environmental conservation and maintaining the quality of life are more likely in low-PDI, low-MAS countries.

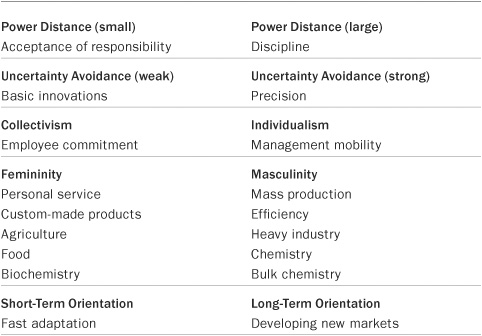

In world business there is a growing tendency for tariff and technological advantages to wear off, which automatically shifts competition, besides toward economic factors, toward cultural advantages or disadvantages. On at least the first five dimensions of national culture, any position of a country offers potential competitive advantages as well as disadvantages; these are summarized in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 serves to show that no country can be good at everything; cultural strengths imply cultural weaknesses. Chapter 10 arrived at a similar conclusion with regard to organizational cultures. This is a strong argument for making cultural considerations part of strategic planning and locating activities in countries, in regions, and in organizational units that possess the cultural characteristics necessary for competing in these activities.

TABLE 11.1 Competitive Advantages of Different Cultural Profiles in International Competition

Most multinational corporations cover a range of businesses and/or product or market divisions, in a range of countries. They have to bridge both national and business cultures.

The purpose of any organizational structure is the coordination of activities. These activities are carried out in business units, each involved in one type of business in one country. The design of a corporate structure is based on three choices, whether explicit or implicit, for each business unit:

Which of the unit’s inputs and outputs should be coordinated from elsewhere in the corporation?

Which of the unit’s inputs and outputs should be coordinated from elsewhere in the corporation?

Where should the coordination take place?

Where should the coordination take place?

How tight or loose should the coordination be?

How tight or loose should the coordination be?

Multinational, multibusiness corporations face the choice between coordination along type-of-business lines or along geographic lines. The key question is whether business know-how or cultural know-how is more crucial for the success of the operation. The classic solution is a matrix structure. This means that every manager of a business unit has two bosses, one who coordinates the particular type of business across all countries, along with one who coordinates all business units in the particular country. Matrix structures are costly, often requiring a doubling of the management ranks, and their functioning may raise more problems than it resolves. That said, a single structural principle is unlikely to fit for an entire corporation. In some cases the business structure should dominate; in others geographic coordination should have priority. The result is a patchwork structure that may lack beauty but that does follow the needs of markets and business unit cultures. Its justification is that variety within the environment in which a company operates should be matched with appropriate internal variety. The diversity in structural solutions advocated is one not only of place but also of time: optimal solutions will very likely change over time, so that periodic reshufflings make sense.

Mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures, and alliances across national borders have become frequent,22 but they remain a regular source of cross-cultural clashes. Cross-national ventures have often turned out to be dramatic failures. Leyland-Innocenti, Vereinigte Flugzeugwerke–Fokker and later DASA-Fokker, Hoogovens-Hoesch and later Hoogovens–British Steel, Citroen-Fiat, Renault-Volvo, Daimler-Chrysler, and Alitalia-KLM are just a few of the more notorious ones. There is little doubt that the list will continue growing as long as management decisions about international ventures are based solely on financial considerations. They are part of a big money and power game and are seen as a defense against (real or imaginary) threats by competitors. Those making the decision rarely imagine the operating problems that can and do arise inside the newly formed hybrid organizations. Even within countries, such ventures have a dubious success record, but across borders they are all the less likely to succeed. If cultural conditions do look favorable, the cultural integration of the new cooperative structure should still be managed; it does not happen by itself. Cultural integration takes lots of time, energy, and money unforeseen by the financial experts who designed the venture.

Five ways of international expansion can be distinguished, in increasing order of cultural risk: (1) the greenfield start, (2) the international strategic alliance, (3) the joint venture with a foreign partner, (4) the foreign acquisition, and (5) the cross-national merger.

The greenfield start means that the corporation sets up a foreign subsidiary from scratch, usually sending over one expatriate or a small team, who will hire locals and gradually build a local branch. Greenfield starts are by their very nature slow, but their cultural risk is limited. The founders of the subsidiary can carefully select employees from the host country who fit the corporation’s culture. The culture of the subsidiary becomes a combination of national elements (mainly values; see Chapter 9) and corporate elements (mainly practices; see Chapter 10). Greenfield starts have a high success rate. IBM, many other older multinationals, and international accounting firms until the 1980s almost exclusively grew through greenfield starts.

The international strategic alliance is a prudent means of cooperation between existing partners. Without creating a new venture, the partners agree to collaborate on specific products and/or markets for mutual benefit. Given that the risks are limited to the project at hand, this is a safe way of learning to know each other; neither party’s existence is at stake. The acquaintance could develop into a joint venture or merger, but in this case the partners can be expected to know each other’s culture sufficiently to recognize the cultural pitfalls.

The joint venture with a foreign partner creates a new business by pooling resources from two or more founding parties. The venture can be started greenfield, or the local partner can transfer part of its people wholesale to the venture. In the latter case, of course, it transfers part of its culture as well. The cultural risk of joint ventures can be controlled by clear agreements about which partner supplies which resources, including what part of management. Joint ventures in which one partner provides the entire management have a higher success rate than those in which management responsibility is shared. Foreign joint ventures can develop new and creative cultural characteristics, based on synergy of elements from the founding partners. They are a limited-risk way of entering an unknown country and market. Not infrequently, eventually one of the partners buys the other(s) out.

In the foreign acquisition a local company is purchased wholesale by a foreign buyer. The acquired company has its own history and its own organizational culture; on top of this it represents a national culture differing from the acquiring corporation’s national culture. Foreign acquisitions are a fast way of expanding, but their cultural risk is considerable. To use an analogy from family life (such analogies are popular for describing the relationships among parts of corporations), foreign acquisitions are to greenfield starts as the bringing up of a foster child, adopted in puberty, is to the bringing up of one’s own child. In regard to the problems of integrating the new member, one solution is to keep it at arm’s length—that is, not to integrate it but to treat it as a portfolio investment. Usually, though, this is not why the foreign company has been purchased. When integration is imperative, the cultural clashes are often resolved by brute power: key people are replaced by the corporation’s own men and women. In other cases key people have not waited for this to happen and have left on their own account. Foreign acquisitions often lead to a destruction of human capital, which is eventually a destruction of financial capital as well. The same applies for acquisitions in the home country, but abroad the cultural risk is even larger. It is advisable for potential foreign (and domestic) acquisitions to be preceded by an analysis of the cultures of the corporation and of the acquisition candidate. If the decision is still to go ahead, such a match analysis can be used as the basis for a culture management plan.

The cross-national merger poses all the problems of the foreign acquisition, plus the complication that power has to be shared. Cultural problems can no longer be resolved by unilateral decisions. Cross-national mergers are therefore extremely risky.23 Even more than in the case of the foreign acquisition, an analysis of the corporate and national cultures of the potential partners should be part of the process of deciding to merge. If the merger is concluded, this analysis can again be the basis of a culture integration plan that needs the active and permanent support of a Machtpromotor (see Chapter 10), probably the chief executive.

Two classic cases of successful cross-national mergers are Royal Dutch Shell (dating from 1907) and Unilever (dating from 1930), both Dutch-British. They show a few common characteristics: the smaller country holds the majority of shares; two head offices have been maintained so as to avoid the impression that the corporation is run from one of the two countries only;24 there has been strong and charismatic leadership during the integration phase; there has been an external threat that kept the partners together for survival; and governments have kept out of the business.

A highly visible international project that is a combination of a strategic alliance and a joint venture is the Airbus consortium in Toulouse, France. Airbus has become one of the two largest aircraft manufacturers in the world. Parts of the planes are manufactured by the participating companies in Britain, Germany, and Spain and then flown over to Toulouse, where the planes are assembled.

Culture is present in the design and quality of many products and in the presentation of many services. An example is the difference in the design of the cockpit in passenger aircraft between Airbus (European, primarily French or German) and Boeing (U.S.). The Airbus has been designed to fly itself with minimum interference from the pilot, while the Boeing design expects more discretion from and interaction with the pilot.25 The Airbus is the product of an uncertainty-avoiding design culture; the Boeing version respects the pilot’s supposed need to feel in command.

In 1983 Harvard University professor Theodore Levitt published an article, “The Globalization of Markets,” in which he predicted that technology and modernity would lead to a worldwide convergence of consumers’ needs and desires. This presumed convergence should enable global companies to develop standard brands with universal marketing and advertising programs. In the 1990s more and more voices in the marketing literature expressed doubts about this convergence and referred to Geert’s culture indexes to explain persistent cultural differences.26 Chapters 4 through 8 provided ample evidence of significant correlations of consumer behavior data with culture dimension indexes, mainly based on research by Marieke de Mooij. Analyzing national consumer behavior data over time, de Mooij showed that contrary to Levitt’s prediction, buying and consumption patterns in affluent countries in the 1980s and ’90s diverged as much as they converged. Affluence implies more possibilities to choose among products and services, and consumers’ choices reflected psychological and social influences. De Mooij wrote:

Consumption decisions can be driven by functional or social needs. Clothes satisfy a functional need, fashion satisfies a social need. Some personal care products serve functional needs, others serve social needs. A house serves a functional, a home a social need. Culture influences in what type of house people live, how they relate to their homes and how they tend to their homes. A car may satisfy a functional need, but the type of car for most people satisfies a social need. Social needs are culture-bound.27

De Mooij’s analysis of the development of the market for private cars across fifteen European countries shows that the number of cars per one thousand inhabitants depended less and less on income: it was strongly related to national wealth in 1969 but no longer in 1994. This finding could be read as a sign of convergence. However, the preference for new over secondhand cars in both periods depended not on wealth but only on uncertainty avoidance: cultures that were uncertainty tolerant continued buying more used cars, without any convergence between countries. Owning two cars in one family in 1970 related to national wealth, but in 1997 it related only to masculinity. In masculine cultures husband and wife each wanted an individual car; in equally wealthy feminine cultures they more often shared a car. In this respect there has been a divergence between countries.28

From the cultural indexes, UAI and MAS resist convergence most: UAI is mostly, and MAS entirely, independent of wealth and therefore unaffected by it. Uncertainty avoidance stands for differences in the need for purity and for expert knowledge; masculinity versus femininity “explains differences in the need for success as a component of status, resulting in a varying appeal of status products across countries. It also explains the roles of males and females in buying and in family decision making.”29 Such differences are often overlooked by globally oriented marketeers who assume their own cultural choices on these dimensions to be universal.

The literature on advertising in the 1990s has increasingly stressed the need for cultural differentiation. On the basis of more than 3,400 TV commercials from eleven countries, de Mooij identified specific advertising styles for countries, linked to cultural themes. For example, single-person pictures are rare in collectivist cultures (if nobody wants to join this person, the product must be bad!). Discussions between mothers and daughters are a theme in TV spots in both large- and small-power-distance cultures, but where PDI is high, mothers advise daughters, and where it is low, daughters advise mothers.30

The same global brand may appeal to different cultural themes in different countries. Advertising, and television advertising in particular, is directed at the inner motivation of prospective buyers. TV commercials can be seen as modern equivalents of the myths and fairy tales of previous generations, told and retold because they harmonize with the software in people’s minds—and in spite of Professor Levitt’s prediction, these minds have not been and will not be globalized.31

Migrant communities have created their own markets across the world, notably in the food industry. Food has strong symbolic links with traditions and with group identity, and migrants—especially those from collectivistic, uncertainty-avoiding cultures—like to retain these links.

Further cultural differentiation, even in firms with globalized marketing approaches, is provided by the intermediate role of local sales forces who translate (sometimes literally) the marketing message to the local customers.32 For example, the degree of directness a salesperson can use is highly culturally dependent. Ways of management and compensation of sales forces should be based on cultural values (theirs and the customers’) and on characteristics of the industry. Conceptions of business ethics for salespersons vary strongly from one culture to another; they are a direct operationalization of some of the values involved in the culture indexes.

Markets for services support globalization even less than the markets for goods. Services are by their nature personalized toward the customer. International companies in the service field tend to leave considerable marketing discretion to local management.

Any traveler in a new country can attest to the insecurity about how to relate to personal service personnel: when to give tips, in what way, and how much. Tipping customs differ by country; they reflect the mutual roles of client and service person. The giving of tips stresses their inequality (power distance) and conflicts with their independence (collectivism).33

Chances for globalization are relatively better for industrial marketing, the business-to-business arena where international purchasers and international salespersons meet. Technical standards are crucial, and participation in their establishment is a major industrial marketing instrument, in which negotiation processes, as described previously, become paramount.

Glen Fisher, a retired U.S. foreign service officer, has written a perceptive book called Mindsets on the role of culture in international relations. In the introduction to the chapter titled “The Cultural Lens,” he states:

Working in international relations is a special endeavor because one has to deal with entirely new patterns of mindsets. To the extent that they can be identified and anticipated for particular groups or even nations, some of the mystery inherent in the conduct of “foreign” affairs will diminish.34