Holistic: referring to a whole that is more than the sum of its parts

Holistic: referring to a whole that is more than the sum of its partsHeaven’s Gate BV (HGBV) is a sixty-year-old production unit in the chemical industry of the Netherlands. Many of its employees are old-timers. Stories about the past abound. Workers tell about how strenuous the jobs used to be, when loading and unloading was done by hand. They tell about the heat and the physical risk. HGBV used to be seen as a rich employer. For several decades the demand for its products exceeded the supply. Products were not sold but were distributed. Customers had to be nice and polite in order to be served. The money was made very easily.

HGBV’s management style used to be paternalistic. The old general manager made his daily morning walk through the plant, shaking hands with everyone he met. This, people say, is the root of a tradition that still exists and which they call the “HGBV grip”: when one arrives in the morning, one shakes hands with one’s colleagues. This greeting ritual would be normal in France, but in the Netherlands it is unusual. Rich and paternalistic, HGBV has long been considered a benefactor, both to its employees in times of need and to the local community. Some of this glory has survived untarnished. Employees still feel HGBV to be a desirable employer, with good pay, benefits, and job security. A job with HGBV is still seen as a job for life. HGBV is a company one would like one’s children to join. Outside, HGBV is a regular sponsor of local sports and humanitarian associations. As they say, “No appeal to HGBV has ever been made in vain.”

The working atmosphere is good-natured, with a lot of freedom given to employees. The plant has been pictured as a club, a village, a family. Twenty-five-year and forty-year service anniversaries are given lots of attention; the plant’s Christmas parties are famous. These celebrations represent rituals with a long history, which people still value. In HGBV’s culture—or, as people express it, “the HGBV way”—unwritten rules for social behavior are important. One doesn’t live in order to work; one works in order to live. What one does counts less than how one does it. One has to fit into the informal network, and this holds for all hierarchical levels. “Fitting” means avoiding conflicts and direct confrontations, covering other people’s mistakes, loyalty, friendliness, modesty, and genial cooperation. Nobody should be too conspicuous, either in a positive or in a negative sense.

HGBVers grumble, but never directly about other HGBVers. Also, grumbling is reserved for one’s own circle; in relations with superiors or outsiders, one does not soil the nest. This concern for harmony and group solidarity fits well into the regional culture of the geographic area in which HGBV is located. Newcomers are quickly accepted, as long as they adapt. The quality of their work counts less than their social adaptation. Whoever disrupts the harmony is rejected, however good a worker he or she is. Disturbed relationships may take years to heal. Says one HGBVer, “We prefer to let a work problem continue for another month, even if it costs a lot of money, above resolving it in an unfriendly manner.” Company rules are never absolute. The most important rule, an interviewee said, is that rules are flexible. One may break a rule if one does it gently. It is not the rule breaker who is at risk, but rather the one who makes an issue of it.

Leadership in HGBV, in order to be effective, should be in harmony with the social behavior patterns. Managers should be accessible, fair, and good listeners. The present general manager is such a leader. He does not give himself airs. He has an easy manner with people of all levels and is felt by employees to be one of them. Careers in HGBV are made primarily on the basis of social skills. One should not behave too conspicuously; one need not be brilliant, but one does need good contacts; one should know one’s way in the informal network, being invited rather than volunteering. One should belong to the tennis club. All in all, one should respect what someone called the strict rules for being a nice person.

This romantic picture, alas, has recently been disturbed by outside influences. First, market conditions have changed, and HGBV finds itself in an unfamiliar competitive situation with other European suppliers. Costs had to be cut, and the workforce reduced. In the HGBV tradition, this problem was resolved without collective layoffs, but instead through early retirement. Still, the old-timers who had to leave prematurely were shocked that the company did not need them anymore.

Second, and even more seriously, HGBV has been attacked by environmentalists because of the pollution it causes, a point of view that has received growing support in political circles. It is not impossible that the licenses necessary for HGBV’s operation will one day be withdrawn. HGBV’s management has tried to counter this problem with an active lobbying effort, with a press campaign, and with organized public visits to the company, but success is by no means certain. Inside HGBV, this threat is belittled. People are unable to imagine that one day there may be no more HGBV: “Our management has always found a solution. There will be a solution now.” In the meantime, attempts are being made to increase HGBV’s competitiveness through quality improvement and product diversification. These initiatives also imply the introduction of new people from the outside. These new trends, however, clash head-on with HGBV’s traditional culture.1

The short case study just presented is a description of an organization’s culture. People working for Heaven’s Gate BV have a specific way of acting and interacting that sets them apart from people working for other organizations, even within the same region. In the past chapters this book has mainly associated culture with nationality. English-language literature attributing cultures to organizations first appeared in the 1960s: organizational culture became a synonym for organizational climate. The equivalent corporate culture, coined in the 1970s, gained popularity after the book Corporate Cultures, by Terrence Deal and Allan Kennedy, appeared in the United States in 1982. The usage became common parlance through the success of a companion volume—like the former, from a McKinsey–Harvard Business School team: Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman’s In Search of Excellence, which appeared in the same year.2 After that, an extensive literature in different languages developed on the topic.

Peters and Waterman wrote:

Without exception, the dominance and coherence of culture proved to be an essential quality of the excellent companies. Moreover, the stronger the culture and the more it was directed toward the marketplace, the less need was there for policy manuals, organization charts, or detailed procedures and rules. In these companies, people way down the line know what they are supposed to do in most situations because the handful of guiding values is crystal clear.3

Talking about the culture of a company or organization became a fad, among managers, among consultants, and, with somewhat different concerns, among academics. Fads pass, and so did this one, but not without having left its traces. Organizational, or corporate, culture has become as fashionable a topic as organizational structure, strategy, and control. There is no standard definition of the concept, but most people who write about it would probably agree that organizational culture is all of the following:

Holistic: referring to a whole that is more than the sum of its parts

Holistic: referring to a whole that is more than the sum of its parts

Historically determined: reflecting the history of the organization

Historically determined: reflecting the history of the organization

Related to the things anthropologists study: such as rituals and symbols

Related to the things anthropologists study: such as rituals and symbols

Socially constructed: created and preserved by the group of people who together form the organization

Socially constructed: created and preserved by the group of people who together form the organization

Soft: although Peters and Waterman assured their readers that “soft is hard”

Soft: although Peters and Waterman assured their readers that “soft is hard”

Difficult to change: although authors disagree on how difficult

Difficult to change: although authors disagree on how difficult

In Chapter 1 culture in general was defined as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others.” Consequently, organizational culture can be defined as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one organization from others.” An organization’s culture, however, is maintained not only in the mind of its members but also in the minds of its other “stakeholders,” everybody who interacts with the organization (such as customers, suppliers, labor organizations, neighbors, authorities, and the press).

Organizations with strong cultures, in the sense of the quote from Peters and Waterman, arouse positive feelings in some people, negative in other people. The universal desirability of having a strong culture from an organizational point of view has frequently been questioned; it could be a source of fatal rigidity.4 The attitude toward strong organizational cultures is partly affected by national culture elements. The culture of IBM Corporation, one of Peters and Waterman’s most excellent companies, was depicted with horror by Max Pagès, a leading French social psychologist, in a 1979 study of IBM France; he called it “la nouvelle église” (“the new church”).5 French society as compared with U.S. society is characterized by a greater dependence of the average citizen on hierarchy and on rules (see Chapters 3, 6, and 9). French academics are also children of their society and therefore more likely than American academics to stress intellectual rules—that is, rational elements in organizations. At the same time, French culture according to Chapter 4 is individualistic, so there is a need to defend the individual against the rational system.6

Dutch sociologist Joseph Soeters showed the similarity between the descriptions of Peters and Waterman’s “excellent companies” and of social movements preaching civil rights, women’s liberation, religious conversion, or withdrawal from civilization. In the United States itself, postcards were sold with the slogan “I’d rather be dead than excellent.” In a more dispassionate way, Soeters’s compatriot Cornelis Lammers showed that the “excellent companies” were simply the latest scion of an entire genealogy within organizational sociology of ideal types of “organic organizations” described already by the German sociologist Joseph Pieper in 1931, if not by others before, and reiterated in the sociological literature on both sides of the Atlantic.7

Another type of reaction was found in the Nordic countries Denmark, Sweden, and, to some extent, Norway and Finland. In their case society is less built on hierarchy and rules than in the United States. The idea of “organizational cultures” in these feminine, uncertainty-tolerant countries was greeted with approval, because it tended to stress the irrational and the paradoxical. This attribute did not at all prevent a basically positive attitude toward organizations.8

In a review of twenty years of organizational culture literature, Swedish sociologist Mats Alvesson distinguishes eight metaphors used by different authors:

Control mechanism for an informal contract

Control mechanism for an informal contract

Compass, giving direction for priorities

Compass, giving direction for priorities

Social glue for identification with the organization

Social glue for identification with the organization

Sacred cow to which people are committed

Sacred cow to which people are committed

Affect-regulator for emotions and their expression

Affect-regulator for emotions and their expression

Mixed bag of conflict, ambiguity, and fragmentation

Mixed bag of conflict, ambiguity, and fragmentation

Taken-for-granted ideas leading to blind spots

Taken-for-granted ideas leading to blind spots

Closed system of ideas and meanings, preventing people from critically exploring new possibilities9

Closed system of ideas and meanings, preventing people from critically exploring new possibilities9

Probably the most basic distinction among writers on organizational cultures exists between those who see culture as something an organization has and those who see it as something an organization is. The former leads to an analytic approach and a concern with change. It predominates among managers and management consultants. The latter supports a synthetic approach and a concern with understanding and is found almost exclusively among academics.10

Using the word culture for both nations and organizations suggests that the two kinds of culture are identical phenomena. This is incorrect: a nation is not an organization, and the two types of culture are of a different nature.

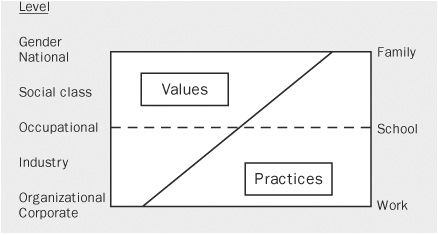

The difference between national and organizational cultures is based on their different mix of values and practices, as illustrated in Figure 10.1, which is based on Figure 1.3. National cultures are part of the mental software we acquired during the first ten years of our lives, in the family, in the living environment, and in school, and they contain most of our basic values. Organizational cultures are acquired when we enter a work organization as young or not-so-young adults, with our values firmly in place, and they consist mainly of the organization’s practices—they are more superficial.11

In Figure 10.1 we also located several other levels of culture: a gender level, even more basic than nationality; a social class level, with some possibilities of ascent or descent; an occupational level, linked to the kind of education chosen; and an industry level between occupation and organization. An industry, or line of business, employs specific occupations and maintains specific organizational practices, for logical or traditional reasons.

FIGURE 10.1 The Balance of Values and Practices for Various Levels of Culture

Among national cultures—comparing otherwise similar people—the IBM studies found considerable differences in values, in the sense described in Chapter 1 of broad, nonspecific feelings of good and evil, and so on. This is notwithstanding similarities in practices among IBM employees in similar jobs but in different national subsidiaries.

When people write about national cultures in the modern world becoming more similar, the evidence cited is usually taken from the level of practices: people dress the same, buy the same products, and use the same fashionable words (symbols); they see the same television shows and movies (heroes); they engage in the same sports and leisure activities (rituals). These relatively superficial manifestations of culture are sometimes mistaken for all there is; the deeper, underlying level of the values, which moreover determine the meaning for people of their practices, is overlooked. Studies at the values level continue to show impressive differences among nations; this is true for not only the IBM studies and their various replications (Table 2.1) but also the successive rounds of the World Values Survey based on representative samples of entire populations.12

Most of the present chapter is based on the results of a research project carried out between 1985 and 1987 under the auspices of the Institute for Research on Intercultural Cooperation (IRIC). It used the cross-national IBM studies as a model. Paradoxically, these studies had not provided direct information about IBM’s corporate culture, as all units studied were from the same corporation, and there were no outside points of comparison. As a complement to the cross-national study, the IRIC study was cross-organizational: instead of one corporation in a number of countries, it covered a number of different organizations in two countries, Denmark and the Netherlands.

The IRIC study found the roles of values versus practices at the organizational level to be exactly the opposite of their roles at the national level. Comparing otherwise similar people in different organizations showed considerable differences in practices but much smaller differences in values.

At that time, the popular literature on corporate cultures, following Peters and Waterman, insisted that shared values represented the core of a corporate culture. The IRIC project showed that shared perceptions of daily practices should be considered the core of an organization’s culture. Employees’ values differed more according to their gender, age, and education (and, of course, their nationality) than according to their membership in the organization per se.

The difference between IRIC’s findings and the statements by Peters and Waterman and their followers can be explained by the fact that the U.S. management literature tends to describe the values of corporate heroes (founders and significant leaders), whereas IRIC asked the ordinary members who are supposed to carry the culture. IRIC assessed to what extent leaders’ messages had come across to members. Without doubt, the values of founders and key leaders shape organizational cultures, but the way these cultures affect ordinary members is through shared practices. Founders’ and leaders’ values become members’ practices.

Effective shared practices are the reason that multinational corporations can function at all. Employing personnel from a variety of nationalities, they cannot assume common values. They coordinate and control their operations through worldwide practices that are inspired by their national origin (be it U.S., Japanese, German, Dutch, etc.) but that can be learned by employees from a variety of other national origins.13

If members’ values depend primarily on criteria other than membership in the organization, the way these values enter the organization is through the hiring process: a company hires people of a certain nationality, gender, age, or education. Their subsequent socialization in the organization is a matter of learning the practices: symbols, heroes, and rituals.

Two Dutch researchers, Joseph Soeters and Hein Schreuder, compared employees in Dutch and foreign accounting firms operating in the Netherlands. They found differences in values between the two groups, but they could prove that these differences were based on self-selection by the candidates, not on socialization to the firm’s values after entering.14 Human resources departments that preselect the people to be hired play an important role in maintaining an organization’s values (for better or for worse), a role of which HR managers—and their colleagues in other functions—are not always conscious.

The original design of the IRIC project had been to compare only organizations within one country (the Netherlands), but finding sufficient Dutch participants willing to grant access and share in the project’s cost proved too difficult. Generous help by a Danish consultant resulted in adding a number of Danish units. Thus, the final project was carried out on twenty units representing ten different organizations: five in Denmark, five in the Netherlands. On the IBM national culture dimensions, these two countries scored fairly similar: both belong to the same Nordic-Dutch cluster. Within these national contexts IRIC sought access to a wide range of work organizations. By seeing how different organization cultures can be, one acquires a better insight into how different is different and how similar is similar. Units of study were both entire organizations and parts of organizations that their management assumed to be culturally reasonably homogeneous (the research outcome later allowed for testing of this assumption).

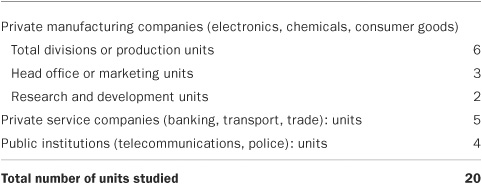

Table 10.1 lists the activities in which the twenty units were engaged. Unit sizes varied from 60 to 2,500 persons. The number of units was small enough to allow studying each unit in depth, qualitatively, as a separate case study. At the same time, it was large enough to permit statistical analysis of comparative quantitative data across all cases.

The first, qualitative phase of the study consisted of in-depth person-to-person interviews of two to three hours duration each with nine informants per unit (thus a total of 180 interviews). These interviews yielded both a qualitative feel for the whole (the gestalt) of the unit’s culture and a collection of issues to be included in the questionnaire for the ensuing survey. Informants were handpicked in a discussion with the person who served as the researchers’ contact in the unit, on the basis that they would have something interesting and informative to relate about the culture. The group of informants included in all cases the unit top manager and his (never her) secretary; along with these were a selection of people in different jobs from all levels, both old-timers and newcomers, women and men. Sometimes the gatekeeper or doorman was found to be an excellent informant; an employee representative (equivalent to a shop steward) was always included.

TABLE 10.1 Organizations Participating in the IRIC Project

The interviewer team consisted of eighteen members (Danish or Dutch), most of them with a social science training but all deliberately naive about the type of activity going on in the unit studied. Each unit’s interviews were divided between two interviewers, one woman and one man, as the gender of the interviewer might affect the observations obtained. All interviewers received the same project training beforehand, and all used the same broad checklist of open-ended questions.

The interview checklist contained questions along the following lines:

About organizational symbols: What are special terms here that only insiders understand?

About organizational symbols: What are special terms here that only insiders understand?

About organizational heroes: What kinds of people are most likely to advance quickly in their careers here? Whom do you consider as particularly meaningful persons for this organization?

About organizational heroes: What kinds of people are most likely to advance quickly in their careers here? Whom do you consider as particularly meaningful persons for this organization?

About organizational rituals: In what periodic meetings do you participate? How do people behave during these meetings? Which events are celebrated in this organization?

About organizational rituals: In what periodic meetings do you participate? How do people behave during these meetings? Which events are celebrated in this organization?

About organizational values: What things do people very much like to see happening here? What is the biggest mistake one can make? What work problems can keep you awake at night?

About organizational values: What things do people very much like to see happening here? What is the biggest mistake one can make? What work problems can keep you awake at night?

Interviewers were free to probe for more and other information if they felt it was there. Interviews were taped, and the interviewers wrote a report on each session using a prescribed sequence, quoting as much as possible the respondents’ actual words.

The second, quantitative phase of the project consisted of a paper-and-pencil survey with precoded questions; contrary to the first phase, it was administered to a strictly random sample from the unit. This sample was composed of about twenty-five managers (or as many as the unit contained), twenty-five college-level nonmanagers (“professionals”), and twenty-five non-college-level nonmanagers. The questions in the survey included those used in the cross-national IBM study plus a number of later additions; most, however, were developed on the basis of the interviews from the first phase. Questions were formulated about all issues that the interviewers suspected to differ substantially between units. These included in particular many perceptions of daily practices, which had been missing in the cross-national studies.

The results of both the interviews and the surveys were discussed with the units’ management and were sometimes fed back to larger groups of employees if the management consented.

The twenty units of focus produced twenty case studies, insightful descriptions of each unit’s culture composed by the interviewers after the one-on-one sessions and with the survey results as a check on their interpretations. The case of Heaven’s Gate BV presented at the beginning of this chapter was taken from the survey results. One more case will now be described: the Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) Copenhagen passenger terminal.

SAS in the early 1980s went through a spectacular turnaround process. Under the leadership of a new president, Jan Carlzon, it switched from a product-and-technology orientation to a market-and-service orientation. Before, planning and sales had been based on realizing a maximum number of flight hours with the most modern equipment available. Pilots, technicians, and disciplinarian managers were the company’s heroes. Deteriorating results forced the reorganization.

Carlzon was convinced that in the highly competitive air transport market, success depended on a superior way of catering to the needs of the present and potential customers. These needs should be best known by the employees who had daily face-to-face customer contact. In the old situation these people had never been asked for their opinions: they were a disciplined set of uniformed soldiers, trained to follow the rules. Now they were considered “the firing line,” and the organization was restructured to support them rather than order them around. Superiors were turned into advisers; the firing line received considerable discretion in dealing with customer problems on the spot. They only needed to report their decisions to superiors after the fact—which meant a built-in acceptance of employees’ judgment with all risks involved.15

One of the units participating in the IRIC study was the SAS passenger terminal at Copenhagen airport. The interviews were conducted three years after the turnaround operation. The employees and managers were uniformed, disciplined, formal, and punctual. They seemed to be the kind of people who like to work in a disciplined structure. People worked shift hours with periods of tremendous work pressure alternating with periods of relative inactivity. They showed considerable acceptance of their new role. When talking about the company’s history, they tended to start from the time of the turnaround; only some managers referred to the earlier years.

The interviewees were demonstrably proud of the company: their identity seemed to a large extent derived from it. Social relationships outside the work situation frequently involved other SAS people. Carlzon was often mentioned as a company hero. In spite of their being disciplined, relationships between colleagues seemed to be good-natured, and there was a lot of mutual help. Colleagues who met with a crisis in their private lives were supported by others and by the company. Managers of various levels were visible and accessible, although clearly managers had more trouble accepting the new role than nonmanagers. New employees entered via a formal introduction and training program that included simulated encounters with problem clients. This program served also as a screening device, showing whether the newcomer had the values and the skills necessary for this profession. Those who successfully completed the training felt quickly at home in the department. Toward clients the employees demonstrated a problem-solving attitude: they showed considerable excitement about original ways in which to resolve customers’ problems, ways in which some rules could be stretched in order to achieve the desired result. Promotion was from the ranks and was felt to go to the most competent and supportive colleagues.

It is not unlikely that this department benefited from a certain “Hawthorne effect”16 because of the key role it had played in a successful turnaround. At the time of the interviews, the euphoria of the successful turnaround was probably at its peak. Observers inside the company commented that people’s values had not really changed but that the turnaround had transformed a discipline of obedience toward superiors into a discipline of service toward customers.

The IBM studies had resulted in the identification of four dimensions of national cultures (power distance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity, and uncertainty avoidance). These were dimensions of values, because the national IBM subsidiaries primarily differed on the cultural values of their employees. The twenty units studied in the IRIC cross-organizational study, however, differed only slightly with respect to the cultural values of their members, but they varied considerably in their practices.

Most questions in the paper-and-pencil survey measured people’s perceptions of the practices in their work unit. These were presented in a “Where I work . . .” format; for example:

Each item thus consisted of two opposite statements: which statement was put in the right column and which in the left column was decided on a random basis, so that their position could not suggest their desirability.

All sixty-one “Where I work . . .” questions were designed on the basis of the information collected in the open interviews and were subjected to a statistical analysis very similar to the one used in the IBM studies. They produced six entirely new dimensions: of practices, not of values. What was used was a factor analysis of a matrix of sixty-one questions by twenty units; for each unit, a mean score was computed on each question across all respondents (who comprised one-third managers, one-third professionals, and one-third nonprofessionals). This analysis produced six clear factors reflecting dimensions of (perceived) practices distinguishing the twenty organizational units from each other. These six dimensions were mutually independent; that is, they occurred in all possible combinations.

Choosing labels for empirically found dimensions is a subjective process: it represents the step from data to theory. The labels chosen have been changed several times. Their present formulation was discussed at length with people in the units. As much as possible, the labels had to avoid suggesting a “good” and a “bad” pole for a dimension. Whether the score of a unit on a dimension should be interpreted as good or bad depends entirely on where the people responsible for managing the unit wanted it to go. The terms finally arrived at are the following:

1. Process oriented versus results oriented

2. Employee oriented versus job oriented

3. Parochial versus professional

4. Open system versus closed system

5. Loose versus tight control

6. Normative versus pragmatic

The order of the six cross-organizational dimensions (their number) reflects the order in which they appeared in the analysis, but it has no theoretical meaning; number 1 is not more important than number 6. A lower number only shows that the questionnaire contained more questions dealing with dimension 1 than with dimension 2, and so on; this can well be seen as a reflection of the interests of the researchers who designed the questionnaire.

For each of the six dimensions, three key “Where I work . . .” questions were chosen to calculate an index value of each unit on each dimension, very much the same way as index values in the IBM studies were computed for each country on each cross-national dimension. The unit scores of the three questions chosen were strongly correlated with each other.17 Their content was such that together they would convey the essence of the dimension, as the researchers saw it, to the managers and the employees of the units in the feedback sessions.

Dimension 1 opposes a concern with means (process oriented) to a concern with goals (results oriented). The three key items show that in the process-oriented cultures, people perceived themselves as avoiding risks and spending only a limited effort in their jobs, while each day was pretty much the same. In the results-oriented cultures, people perceived themselves as comfortable in unfamiliar situations and as putting in a maximal effort, while each day was felt to bring new challenges. On a scale from 0 to 100, in which 0 represents the most process-oriented unit and 100 the most results-oriented unit among the twenty, HGBV, the chemical plant described earlier, scored 2 (very process oriented, little concern for results), while the SAS passenger terminal scored 100: it was the most results-oriented unit of all. For this dimension it is difficult not to attach a “good” label to the results-oriented pole and a “bad” label to the other side. Nevertheless, there are operations for which a single-minded focus on the process is essential. The most process-oriented unit (score 0) was a production unit in a pharmaceutical firm. Drug manufacturing is an example of a risk-avoiding, routine-based environment in which it is doubtful whether one would want its culture to be results oriented. Similar concerns exist in many other organizational units. So, even a results orientation is not always “good” and its opposite not always “bad.”

One of the main claims from Peters and Waterman’s book In Search of Excellence was that “strong” cultures are more effective than “weak” ones. A problem in verifying this proposition was that in the corporate culture literature one would search in vain for a practical (operational) measure of culture strength. As the issue seemed important, the IRIC project developed a method for measuring the strength of a culture. A strong culture was interpreted as a homogeneous culture—that is, one in which all survey respondents gave about the same answers on the key questions, regardless of the content of the questions. A weak culture was a heterogeneous one: this type was evidenced when answers among people in the same unit varied widely. The survey data showed that across the twenty units studied, culture strength (homogeneity) was significantly correlated with results orientation.18 To the extent that results oriented stands for effective, Peters and Waterman’s proposition about the effectiveness of strong cultures was therefore confirmed.

Dimension 2 opposes a concern for people (employee oriented) to a concern for completing the job (job oriented). The key items selected show that in the employee-oriented cultures, people felt that their personal problems were taken into account, that the organization took a responsibility for employee welfare, and that important decisions were made by groups or committees. In the job-oriented units, people experienced strong pressure to complete the job; they perceived the organization as interested only in the work employees did, not in their personal and family welfare; and they reported that important decisions were made by individuals. On a scale from 0 to 100, HGBV scored 100 and the SAS passenger terminal 95—both of them extremely employee oriented. Scores on this dimension reflected the philosophy of the unit or company’s founder(s), but they reflected as well the possible scars left by past events: units that had recently been in economic trouble, especially if this had been accompanied by collective lay-offs, tended to score job oriented, even if according to informants the past had been different. Opinions about the desirability of a strong employee orientation differed among the leaders of the units in the study. In the feedback discussions some top managers wanted their unit to become more employee oriented, but others desired a move in the opposite direction.

The employee-oriented versus job-oriented dimension corresponds to the two axes of a classic U.S. leadership model: Robert Blake and Jane Mouton’s managerial grid.19 Blake and Mouton developed an extensive system of leadership training on the basis of their model. In this training, employee orientation and job orientation are treated as two independent dimensions: a person can be high on both, on one, or on neither. This treatment seems to be in conflict with our placing of the two orientations at opposite poles of a single dimension. However, Blake and Mouton’s grid applies to individuals, while the IRIC study compared organizational units. What the IRIC study shows is that while individuals may well be both job oriented and employee oriented at the same time, organizational cultures tend to favor one or the other.

Dimension 3 opposes units whose employees derive their identity largely from the organization (parochial) to units in which people identify with their type of job (professional). The key questions show that members of parochial cultures felt that the organization’s norms covered their behavior at home as well as on the job; they felt that in hiring employees, the company took their social and family background into account as much as their job competence; and they did not look far into the future (they probably assumed the organization would do this for them). On the other side, members of professional cultures considered their private lives their own business, they felt the organization hired on the basis of job competence only, and they did think far ahead. U.S. sociologist Robert Merton has called this distinction local versus cosmopolitan, the contrast between an internal and an external frame of reference.20 The parochial type of culture is often associated with Japanese companies. Predictably in the IRIC survey, unit scores on this dimension were correlated with the unit members’ level of education: parochial units tended to have employees with less formal education. SAS passenger terminal employees scored quite parochial (24); HGBV employees scored about halfway (48).

Dimension 4 opposes open systems to closed systems. The key items show that in the open system units, members considered both the organization and its people open to newcomers and outsiders; almost anyone would fit into the organization, and new employees needed only a few days to feel at home. In the closed system units, the organization and its people were felt to be closed and secretive, even among insiders; only very special people fitted into the organization, and new employees needed more than a year to feel at home (in the most closed unit, one member of the managing board confessed that he still felt like an outsider after twenty-two years). On this dimension, HGBV again scored halfway (51) and SAS extremely open (9). What this dimension describes is the communication climate. It was the only one of the six “practices” dimensions associated with nationality: it seemed that an open organizational communication climate was a characteristic of Denmark more than of the Netherlands. However, one Danish organization scored very closed.

Dimension 5 refers to the amount of internal structuring in the organization. According to the key questions, people in loose control units felt that no one thought of cost, meeting times were only kept approximately, and jokes about the company and the job were frequent. People in tight control units described their work environment as cost-conscious, meeting times were kept punctually, and jokes about the company and/or the job were rare. It appears from the data that a tight formal control system is associated, at least statistically, with strict unwritten codes in terms of dress and dignified behavior. On a scale where 0 equals loose and 100 equals tight, SAS with its uniformed personnel scored extremely tight (96), and HGBV scored once more halfway (52); halfway, though, was quite loose for a production unit, as a comparison with other production units showed.

Dimension 6, finally, deals with the popular notion of customer orientation. Pragmatic units were market driven; normative units perceived their task in relation to the outside world as the implementation of inviolable rules. The key items show that in the normative units, the major emphasis was on correctly following organizational procedures, which were more important than results; in matters of business ethics and honesty, the unit’s standards were felt to be high. In the pragmatic units, there was a major emphasis on meeting the customer’s needs; results were more important than correct procedures; and in matters of business ethics, a pragmatic rather than a dogmatic attitude prevailed. The SAS passenger terminal was the top-scoring unit on the pragmatic side (100), which shows that Jan Carlzon’s message had come across. HGBV scored 68, also on the pragmatic side. In the past as it was described in the HGBV case study, the company might have been more normative toward its customers, but it seemed to have adapted to its new competitive situation.

Inspection of the scoring profiles of the twenty units on the six dimensions shows that dimensions 1, 3, 5, and 6 (process versus results, parochial versus professional, loose versus tight, and normative versus pragmatic) relate to the type of work the organization does and to the type of market in which it operates. These four dimensions partly reflect the industry (or business) culture according to Figure 10.1. On dimension 1, most manufacturing and large office units scored process oriented; research and development units and service units scored more results oriented. On dimension 3, units with a traditional technology scored parochial; high-tech units scored professional. On dimension 5, units delivering precision or risky products or services (such as pharmaceuticals or money transactions) scored tight; those with innovative or unpredictable activities scored loose. To the researchers’ surprise, the two city police forces studied scored on the loose side (16 and 41): the work of a police officer, however, is highly unpredictable, and police personnel have considerable discretion in the way they want to carry out their tasks. On dimension 6, service units and those operating in competitive markets scored pragmatic; units involved in the implementation of laws and those operating under a monopoly scored normative.

While the task and market environment thus affect the dimension scores, the IRIC study, as noted, also produced its share of surprises: production units with an unexpectedly strong results orientation even on the shop floor, along with a unit such as HGBV with a loose control system in relation to its task. These surprises represent the distinctive elements in a unit’s culture (as compared with similar units) and the competitive advantages or disadvantages of a particular organizational culture.

The other two dimensions, 2 and 4 (employee versus job and open versus closed), seem to be less constrained by task and market but rather based on historical factors such as the philosophy of the founder(s) and recent crises. In the case of dimension 4, open versus closed system, the national cultural environment was already shown to play a role as well.

Figure 10.1 indicates that although organizational cultures are mainly composed of practices, they do have a modest values component. The cross-organizational IRIC survey included the values questions from the cross-national IBM studies. The organizations differed somewhat on three clusters of values. The first resembled the cross-national dimension of uncertainty avoidance, although the differences showed up on other survey questions than those used for computing the country UAI scores. The cross-organizational uncertainty-avoidance measure was correlated with dimension 4 (open versus closed), with weak uncertainty avoidance obviously on the side of an open communication climate. The relationship was reinforced by the fact that the Danish units, with one exception, scored more open than the Dutch ones. Denmark and the Netherlands, though similar on most national culture scores, differed most on their national uncertainty avoidance scores, Denmark scoring much lower.

A second cluster of cross-organizational values bore some resemblance to power distance. It was correlated with dimension 1 (process oriented versus results oriented): larger power distances were associated with process orientation and smaller ones with results orientation.

Clusters of cross-organizational value differences associated with individualism and masculinity were not found in the IRIC study. It is possible that this was because the study was restricted to business organizations and public institutions. If, for example, health and welfare organizations had been included, the study might have shown a wider range of values with regard to helping other people, which would have produced a feminine-masculine dimension.

Questions that in the cross-national study composed the individualism and masculinity dimensions appeared in the cross-organizational study in a different configuration. It was labeled work centrality (strong or weak): the importance of work in one’s total life pattern. It was correlated with dimension 3: parochial versus professional. Work centrality obviously is stronger in professional organization cultures. In parochial cultures, people do not take their work problems home.

From the six organizational culture dimensions, numbers 1, 3, and 4 were thus to some extent associated with values. For the other three dimensions—2, 5, and 6—no link with values was found at all. These dimensions just described practices to which people had been socialized without their basic values being involved.

In the IBM studies, a national culture’s antecedents and consequences were proved by correlating the country scores with all kinds of external data. These included such economic indicators as the country’s gross national income per capita, political measures such as an index of press freedom, and demographic data such as the population growth rate. Comparisons were also made with the results of other surveys that covered the same countries but used different questions and different respondents. The IRIC cross-organizational study included a similar “validation” of the dimensions against external data. This time, of course, the data used consisted of information about the organizational units obtained in other ways and from other sources.

Besides the interviews and the survey, the IRIC study included the collection of quantifiable data about the units as wholes. Examples of such information (labeled structural data) are total employee strength, budget composition, economic results, and the ages of key managers. All structural data were personally collected by Geert. Finding out what meaningful structural data could be obtained was a heuristic process that went along with the actual collection of the data. This process was too complicated to be shared across researchers. The informants for the structural data were the top manager, the chief personnel officer, and the chief budget officer. They were presented with written questionnaires, followed up by personal interviews.

Out of a large number of quantifiable characteristics tried, about forty provided usable data. For these forty characteristics, the scores for each of the twenty units were correlated with the unit scores on the six practices dimensions.21 In the following paragraphs, for each of the six practice dimensions the most important relationships found are described.

There was a strong correlation between the scores on practice dimension 1, process orientation versus results orientation, and the balance of labor cost versus material cost in the operating budget (the money necessary for daily functioning). An operation can be characterized as labor-intensive, material-intensive, or capital-intensive, depending on which of the three categories of cost takes the largest share of its operating budget. Labor-intensive units (holding number of employees constant) scored more results oriented, while material-intensive units (again holding number of employees constant) scored more process oriented. If an operation is labor-intensive, the effort of people by definition plays an important role in its results. This situation appears more likely to breed a results-oriented culture. The yield of material-intensive and capital-intensive units tends to depend on technical processes, which fact seems to stimulate a process-oriented culture. It is therefore not surprising that one finds research and development units and service units on the results-oriented side; manufacturing and office units, subject to more automation, are more often found on the process-oriented side.

The second-highest correlation of results orientation was with lower absenteeism. This is a nice validation of the fact that, as one of the key questions formulated it, “people put in a maximal effort.” Next there were three significant correlations between results orientation and the structure of the organizations. Flatter organizations (larger span of control for the unit top manager) scored more results oriented. This confirms one of Peters and Waterman’s maxims: “simple form, lean staff.” Three simplified scales were used based on the Aston Studies of organizational structure referred to in Chapter 9,22 measuring centralization, specialization, and formalization. Both specialization and formalization were negatively correlated with results orientation: more specialized and more formalized units tend to be more process oriented. Centralization was not correlated with this dimension. Results orientation was also correlated with having a top-management team with a lower education level and promoted from the ranks. Finally, in results-oriented units, union membership among employees tended to be lower.

The strongest correlations with dimension 2 (employee orientation versus job orientation) were with the way the unit was controlled by the organization to which it belonged. Where the top manager of the unit stated that his superiors evaluated him on profits and other financial performance measures, the members scored the unit culture as job oriented. Where the top manager of the unit felt that his superiors evaluated him on performance versus a budget, the opposite was the case: members scored the unit culture to be employee oriented. It seems that operating against external standards (profits in a market) breeds a less benevolent culture than operating against internal standards (a budget). Where the top manager stated that he allowed controversial news to be published in the employee newsletter, members felt the unit to be more employee oriented, which validated the top manager’s veracity.

The remaining correlations of employee orientation were with the average seniority (years with the company) and age of employees (more senior employees scored a more job-oriented culture), with the education level of the top-management team (less-educated teams correspond with a more job-oriented culture), and with the total invested capital (surprisingly, not with the invested capital per employee). Large organizations with heavy investment tended to be more employee oriented than job oriented.

On dimension 3 (parochial versus professional), units with a traditional technology tended to score parochial and high-tech units professional. The strongest correlations of this dimension were with various measures of size: it was not unexpected that the larger organizations fostered the more professional cultures. Also as could be expected, professional cultures had less labor union membership. Their managers had a higher average education level and age. Their organizational structures showed more specialization. An interesting correlation was with the time budget of the unit top manager, by which is meant the way the unit top manager claimed to spend his time. In the units with a professional culture, the top managers claimed to spend a relatively large share of their time in meetings and person-to-person discussions. Finally, the privately owned units tended to score more professional than the public ones.

Dimension 4 (open versus closed system) was responsible for the single strongest correlation with external data: between the percentage of women among the employees and the openness of the communication climate.23 The percentage of women among managers and the presence of at least one woman in the top-management team were also correlated with openness. However, this correlation was affected by the binational composition of the research population. Among developed European countries, Denmark at the time of the research had one of the highest participation rates of women in the workforce, while the Netherlands had one of the lowest. Also, as mentioned earlier, Danish units as a group (with one exception) scored more open than Dutch units. This does not necessarily exclude a causal relationship between the participation of women in the workforce and a more open communication climate: it could very well be the explanation as to why the Danish units were so much more open.

Also connected with the open versus closed dimension were the associations of formalization with a more closed culture (a nice cross-validation of both measures), of allowing controversial issues in the employee newsletter with an open culture (obviously), and of higher average seniority with a more open culture.

The strongest correlation of dimension 5 (loose versus tight control) was with an item in the self-reported time budget of the unit top manager: where the top manager claimed to spend a relatively large part of his time reading and writing reports and memos from inside the organization, control was found to be tighter. This finding makes perfect sense. We also found that material-intensive units have more tightly controlled cultures. As the results of such units often depend on small margins of material yields, this makes sense too.

Tight control was also correlated with the percentage of female managers and of female employees, in that order. This was most likely a consequence of the simple, repetitive, and clerical activities for which, in the organizations studied, the larger numbers of women tended to be hired. Tighter control was found in units with a lower education level among male and female employees and also among its top managers. This reminds us of the finding in Chapter 3 that employees in lower-educated occupations maintained larger power distances. In units in which the number of employees had recently increased, control was felt to be looser; where the number of employees had been reduced, control was perceived as tighter. Employee layoffs are obviously associated with budget squeezes. Finally, absenteeism among employees was lower where control was perceived to be less tight. Absenteeism is evidently one way of escape from the pressure of a tight control system.

For dimension 6 (normative versus pragmatic), only one meaningful correlation with external data was found. Privately owned units in the sample were more pragmatic, public units (such as the police departments) more normative.

Missing from the list of external data correlated with culture were measures of the organizations’ performance. This does not mean that culture is not related to performance; it means only that the research did not find comparable yardsticks for the performance of so varied a set of organizational units.

The relationships described in this section show objective conditions of organizations that were associated with particular culture profiles. They point to the things one has to change in order to modify an organization’s culture—for example, certain aspects of its structure, or the priorities of the top manager. We will come back to this theme at the end of the chapter.

A follow-up study by IRIC investigated organizational subcultures.24 In 1988 a Danish insurance company commissioned IRIC to study the cultures of all its departments, surveying its total population of 3,400 employees. The study used the same approach as the previous Danish-Dutch project: open-ended interviews leading to the composition of a survey questionnaire.

The total respondent population could be divided into 131 “organic” working groups. These were the smallest building blocks of the organization, whose members had regular face-to-face contact. Managers were not included in the groups they managed but were combined with colleagues at their level of the hierarchy.

On the basis of their survey answers, the 131 groups could be sorted into three clearly distinct subcultures: a professional, an administrative, and a customer interface subculture. The first included all managers and employees in tasks for which a higher education was normally required, the second all the (mostly female) employees in clerical departments, and the third two groups of employees dealing directly with customers: salespeople and claim handlers.

Using the six dimensions from the Danish-Dutch study, the researchers showed various culture gaps among the three subcultures. The professional groups were the most job oriented, professional, open, tightly controlled, and pragmatic; the administrative groups the most parochial and normative; the customer interface groups the most results and employee oriented, closed, and loosely controlled. The customer interface subculture represented a counterculture to the professional culture.

Just before the survey was conducted, the company had gone through two cases of internal rebellion: from the salespeople and from the women. The sales rebellion had been a conflict about working conditions and compensation; a sales strike had only just been prevented. This problem can be understood from the wide gap between the professional and customer interface subcultures. This rift on the culture map of the company proved dangerous. The customer interface people generate the business—without them, an insurance company cannot survive. The managers and professionals who made the key decisions in this company belonged to a notably different subculture: a high-profile, glorified environment in which big money, business trends, and market power were daily concerns—far from the crowd who did the actual work and brought in the daily earnings.

The women’s rebellion was about a lack of careers for women, and it happened when the share of female employees had passed the 50 percent mark. The rebellion can be understood by looking at the gap between the professional and the administrative subcultures. Management, from their professional subculture, saw women as belonging to the administrative subculture: employees in routine jobs, not upwardly mobile. But this image was no longer accurate, if it had ever been so. Of the 1,700 women in the company, 700 had a higher education; many worked in professional roles, and even those in administrative roles were nearly as much interested in a career as their male colleagues. The interviews had revealed that managers believed most women to experience conflicts between their work and their private and family lives. The survey, however, showed that whereas 21 percent of the women employees claimed to suffer from such conflicts, 30 percent of the men did. The women’s explanation of this result was that if a woman took a job, she had to have her family problems resolved, whereas many men never consciously resolved them.

For an understanding of the culture of this insurance company, the subculture split was essential. Unfortunately, the members of management—caught in their professional culture—did not recognize the alarming aspects of the culture rifts. They took little action as a result of the survey. Soon afterward the company started losing money; a few years later it changed ownership and top management.

Different individuals within the same organizational unit do not necessarily give identical answers to questions about how they see their organization’s practices. The IRIC study did not look at differences among individuals: its concern was with differences among organizational cultures. Michael Bond, at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who was interested in individual differences, offered to reanalyze the IRIC database from this point of view. Chung-Leung Luk, at that time Bond’s assistant, performed the necessary computer work. His results show the structure in the variation of individual scores around the means of the organizational units: in what ways individuals’ answers differed after organization culture differences were eliminated. This extension of the IRIC project has been described in a joint paper by Hofstede, Bond, and Luk.25

The individual perceptions study first analyzed the values questions and the practices questions separately. As is natural, individuals within the same unit differed more in their values, which were private, than in their perceptions of the unit’s practices, in which they shared. Yet it became clear that for individuals, values and perceptions of practices were related, so in the further analysis they could be combined. This combination produced six dimensions of individuals’ answers:

1. Alienation, a state of mind in which all perceptions of practices were negative. Alienated respondents were misers: they scored the organization as less professional, felt management to be more distant, trusted colleagues less, saw the organization as less orderly, felt more hostile to it, and perceived less integration between the organization and its employees. Alienation was stronger among employees who were younger, less educated, and nonmanagerial.

2. Workaholism, a term chosen by the researchers for a strong commitment to work (for example, the job is more important than leisure time), as opposed to a need for a supportive organization (for example, wanting to work in a well-defined job situation). Workaholism was stronger among employees who were younger, more educated, male, and managerial.

3. Ambition, or personal need for achievement (for example, wanting to contribute to the success of the organization and wanting opportunities for advancement).

4. Machismo, or personal masculinity (for example, parents should stimulate children to be best in class, and when a man’s career demands it, the family should make sacrifices).

5. Orderliness; employees who had more orderly minds saw the organization as more orderly.

6. Authoritarianism (for example, it is undesirable that management authority can be questioned). Authoritarianism was stronger for employees who were less educated and female.

Systematic individual differences in perceptions of organizational cultures are most likely based on personality. In fact, five of the dimensions listed here resemble the Big Five dimensions of personality described in Chapter 2 (openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism). The individual perceptions dimensions can be associated with Big Five dimensions as follows:26

1. Alienation with neuroticism

2. Workaholism with extraversion (which includes active and energetic)

3. Ambition with openness to experience

4. Machismo negatively with agreeableness

5. Orderliness with conscientiousness

No personality factor was available for an association with authoritarianism, which surprised us. In Chapter 2 we described how Geert and Big Five author Robert R. McCrae found mean personality scores for comparative samples from thirty-three countries to correlate significantly with all four IBM culture dimensions, but not with long-term orientation.27 Geert wondered whether this could be explained from the fact that both classifications were conceived by Western minds. Could the Big Five model miss out on a personality dimension that across countries might relate to long-versus short-term orientation?

There is research evidence suggesting that the Big Five personality measure, developed in the West, may be incomplete in Asia.28 Findings from China and the Philippines yielded a sixth personality factor: interpersonal relatedness, or gregariousness. Our organizational culture study located in Europe, meanwhile, missed a personality factor related to authoritarianism.

Gregariousness and authoritarianism may be interpreted as two facets of a common sixth personality factor, dealing with dependence on others. Across countries, this might very well correlate with long-term orientation. Extending the Big Five to a Big Six may increase its cross-cultural universality.29

The choice of a level of analysis, as discussed in Chapters 1 and 2, has figured prominently in the present chapter. When we compared the same kind of data across countries, across organizational units, and across individuals, we found three different sets of dimensions, belonging to three different social science disciplines: anthropology, sociology, and psychology.

The cross-national study of the IBM data took what were first supposed to be psychological data and aggregated them to the country level. At that level they melted into concepts describing societies, such as collectivism versus individualism, which really belong to anthropology and/or to political science. The database of the IRIC organizational culture study, analyzed at the level of organizational units, produced basic distinctions from organizational sociology, like Merton’s local versus cosmopolitan. The same database, analyzed at the level of individual differences from the organizational unit’s mean, supported the results of personality research in individual psychology.

Societies, organizations, and individuals represent the gardens, bouquets, and flowers of social science. Our research has shown that the three are related and part of the same social reality. If we want to understand our social environment, we cannot fence ourselves into the confines of one level only: we should be prepared to count with all three.30

In Figure 10.1 an occupational culture level was placed halfway between nation and organization, because entering an occupational field means the acquisition of both values and practices; the place of socialization is the school, apprenticeship, or university, and the time is between childhood and entering work.

We know of no broad cross-occupational study that allows identifying dimensions of occupational cultures. Neither the five national culture (values) dimensions nor the six organizational culture (practices) dimensions will automatically apply to the occupational level. From the five cross-national dimensions, only power distance and masculinity-femininity were applicable to occupational differences in IBM. Chapter 4 showed that IBM occupations could not be described in terms of “individualist” or “collectivist,” but rather as “intrinsic” or “extrinsic” according to what motivated most of those engaged in the occupation, the work itself or the conditions and the material rewards provided.

From a review of the literature and some guesswork, we predict that in a systematic cross-occupational study the following dimensions of occupational cultures may well be found:31

1. Handling people versus handling things (for example, nurse versus engineer)

2. Specialist versus generalist—or, from a different perspective, professional versus amateur (for example, psychologist versus politician)

3. Disciplined versus independent (for example, police officer versus shopkeeper)32

4. Structured versus unstructured (for example, systems analyst versus fashion designer)

5. Theoretical versus practical (for example, professor versus sales manager)

6. Normative versus pragmatic (for example, judge versus advertising agent)

These dimensions will have stronger associations with practices than the national culture dimensions and stronger associations with values than the organizational culture dimensions. They may also be used for distinctions within professions; for example, medical specialists can be placed on a “handling people versus handling things” continuum, with pediatricians landing far on the handling people side (they often deal with not only the child but the family as well) and surgeons and pathologists, who focus on details of the body, far on the handling things side.

The IRIC research project produced a six-dimensional model of organizational cultures, defined as perceived common practices: symbols, heroes, and rituals. The research data came from twenty organizational units in two northwestern European countries, and one should therefore be careful not to claim that the same model applies to any organization anywhere. Certain important types of organizations, such as those concerned with health and welfare, government, and the military, were not included.33 We do not know what new practice dimensions may still be found in other countries. Nevertheless, we believe that the fact that organizational cultures can be meaningfully described by a number of practice dimensions is probably universally true. Also, it is likely that such dimensions will generally resemble, and partly overlap, the six described in this chapter.34

The geographic and industry limitations of the six-dimensional model imply that our questionnaire is not suitable for blanket replications. Interpreting the results is a matter of comparison. The formulas we used for computing the dimension scores were made for comparing an organization with the twenty units in the IRIC study, but they are meaningless in other environments and at other times. New studies should choose their own units to compare and develop their own standards for comparison. They should again start with interviews across the organizations to be included, in order to get a feel for the organizations’ gestalts, and then compose their own questionnaire covering the crucial differences in the practices of these organizations.35

The dimensions found describe the culture of an organization, but they are not prescriptive: no position on one of the six dimensions is intrinsically good or bad. In Peters and Waterman’s book In Search of Excellence, eight conditions for excellence were presented as norms. Their book suggested there is one best way toward excellence. The results of the IRIC study refute this. What is good or bad depends in each case on where one wants the organization to go, and a cultural feature that is an asset for one purpose is unavoidably a liability for another. Labeling positions on the dimension scales as more or less desirable is a matter of strategic choice, and this process will vary from one organization to another. In particular, a stress on customer orientation (becoming more pragmatic on dimension 6) is highly relevant for organizations engaged in services and the manufacturing of custom-made quality products but may be unnecessary or even harmful for, say, the manufacturing of standard products in a competitive price market.

This chapter referred earlier to the controversy about whether an organization is or has a culture. On the basis of the IRIC research project, we propose that practices are features an organization has. Because of the important role of practices in organizational cultures, the latter can be considered somewhat manageable. We saw that changing collective values of adult people in an intended direction is extremely difficult, if not impossible. Collective practices, however, depend on organizational characteristics such as structures and systems, and they can be influenced in more or less predictable ways by changing these organizational characteristics. Nevertheless, as argued previously, organization cultures are also in a way integrated wholes, or gestalts, and a gestalt can be considered something the organization is. Organizations are sometimes compared to animals; thus, HGBV could be pictured as an elephant (slow, bulky, self-confident) and the SAS passenger terminal as a stork (reliable, caring, transporting). The animal metaphor suggests limits to the changeability of the gestalt; one cannot train an elephant to become a racehorse, let alone to become a stork.

Changes in practices represent the margin of freedom in influencing these wholes, the kinds of things the animals can learn without losing their essence. Because they are wholes, an integrating and inspiring type of leadership is needed to give these structural and systems changes a meaning for the people involved. The outcome should be a new and coherent cultural pattern, as was illustrated by the SAS case.

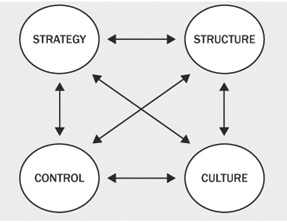

Back in the 1980s, when Geert tried to sell participation in the organizational culture research project to top managers of organizations, he claimed that “organizational culture represents the psychological assets of the organization that predict its material assets in five years’ time.” As we see it now, the crucial element is not the organizational culture itself, but what (top) management does with it. Four aspects have to be balanced (Figure 10.2).36

The performance of an organization should be measured against its objectives, and top management’s role is to translate objectives into strategy—even if by default all that emerges is a laissez-faire strategy. Strategies are carried out via the existing structure and control system, and their outcome is modified by the organization’s culture—and all four of these elements influence each other.

FIGURE 10.2 Relationships Among Strategy, Structure, Control, and Culture

The IRIC study has shown that, as long as quantitative studies of organizational cultures are not used as isolated tricks but are integrated into a broader approach, they are both feasible and useful. In a world of hardware and bottom-line figures, the scores make organizational culture differences visible; by becoming visible, they move up on management’s priority list.

Practical uses of such a study for managers and members of organizations, as well as for consultants, are listed here:

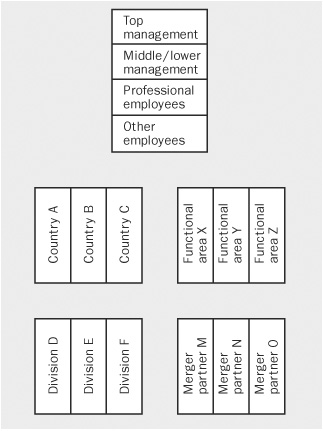

Identifying the subcultures in one’s own organization. The extension of the IRIC project to the insurance company demonstrated the importance of this application. As Figure 10.3 illustrates, organizations may be culturally divided according to hierarchical levels: top management, middle-and lower-level managers, professional employees, and other employees (office or shop floor). Other potential sources of internal cultural divisions are functional area (such as sales versus production versus research), product/market division, country of operation, and, for organizations having gone through mergers, former merger partners. We have met cases in which twenty years after a merger the cultural traces of the merged parts could still be found as slightly different moral circles (see Chapter 1). Not all of these potential divisions will be equally strong, but it is important for the managers and members of a complex organization to know its cultural map—which, as we found, is not always the case.

Identifying the subcultures in one’s own organization. The extension of the IRIC project to the insurance company demonstrated the importance of this application. As Figure 10.3 illustrates, organizations may be culturally divided according to hierarchical levels: top management, middle-and lower-level managers, professional employees, and other employees (office or shop floor). Other potential sources of internal cultural divisions are functional area (such as sales versus production versus research), product/market division, country of operation, and, for organizations having gone through mergers, former merger partners. We have met cases in which twenty years after a merger the cultural traces of the merged parts could still be found as slightly different moral circles (see Chapter 1). Not all of these potential divisions will be equally strong, but it is important for the managers and members of a complex organization to know its cultural map—which, as we found, is not always the case.

FIGURE 10.3 Potential Subdivisions of an Organization’s Culture

Testing whether the culture fits the strategies set out for the future. Cultural constraints determine which strategies are feasible for an organization and which are not. For example, if a culture is strongly normative, a strategy for competing on customer service has little chance of success.

Testing whether the culture fits the strategies set out for the future. Cultural constraints determine which strategies are feasible for an organization and which are not. For example, if a culture is strongly normative, a strategy for competing on customer service has little chance of success.

In the case of mergers and acquisitions, identifying the potential areas of culture conflict between the partners. This can be either an input to the decision on whether to merge, or, if the decision has been made, an input to a plan for managing the postmerger integration so as to minimize friction losses and preserve unique cultural capital.

In the case of mergers and acquisitions, identifying the potential areas of culture conflict between the partners. This can be either an input to the decision on whether to merge, or, if the decision has been made, an input to a plan for managing the postmerger integration so as to minimize friction losses and preserve unique cultural capital.

Measuring the development of organizational cultures over time, by repeating a survey after one of more years. This will show whether attempted culture changes have, indeed, materialized, as well as identify the cultural effects of external changes that occurred after the previous survey.

Measuring the development of organizational cultures over time, by repeating a survey after one of more years. This will show whether attempted culture changes have, indeed, materialized, as well as identify the cultural effects of external changes that occurred after the previous survey.