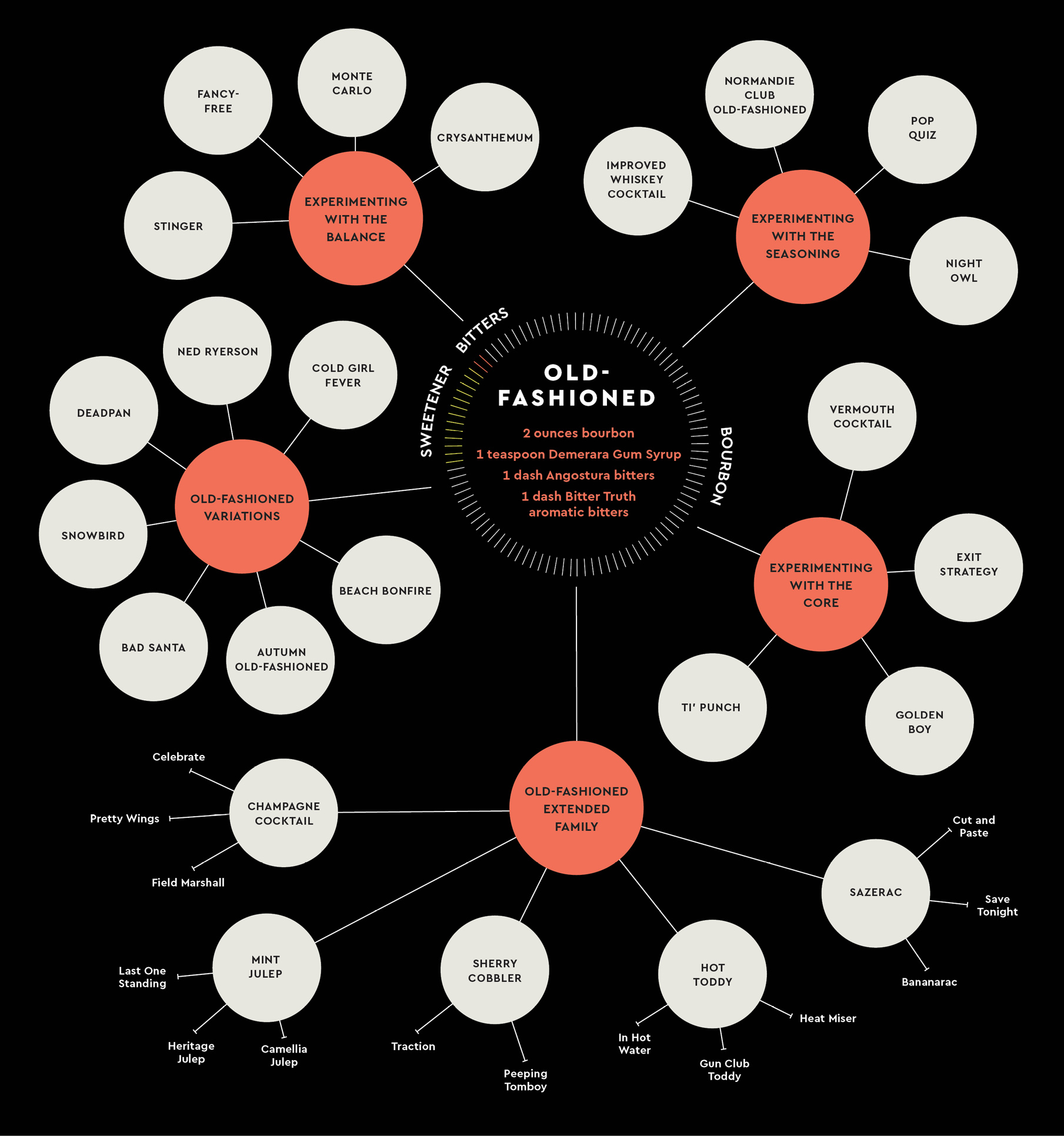

THE OLD-FASHIONED EXTENDED FAMILY

By manipulating the Old-Fashioned template, you can create whole new categories of drinks. What connects the root recipe and the recipes in the extended family is that they all focus on a core flavor and contain only small amounts of sweetener and seasoning. In the recipes that follow, we’ve highlighted our versions of some classic recipes, each followed by some of our own original cocktails inspired by these classics.

Champagne Cocktail

CLASSIC

A Champagne Cocktail is essentially an Old-Fashioned in which Champagne stands in for the whiskey. Because of the lower alcohol content of the Champagne, partially diluting the drink as you would an Old-Fashioned doesn’t make sense, and, of course, the bubbles in the Champagne wouldn’t be well served by stirring. Therefore, this drink is built in a flute. Given that it isn’t stirred over ice, like an Old-Fashioned, be sure to start with cold Champagne.

1 sugar cube

Angostura bitters

Dry Champagne

Garnish: 1 lemon twist

Place the sugar cube on a paper towel. Dash the bitters over the sugar cube until it’s completely saturated. Drop the sugar cube into a chilled flute and slowly top with Champagne; don’t stir. Express the lemon twist over the drink, then place it into the drink.

SPARKLING WINES

In cocktails, sparkling wine does multiple things: it adds effervescence, proof (alcoholic content), flavor, acidity, and sweetness. It’s extremely helpful to become familiar with specific bottles and how each will impact recipes. But more fundamentally, it’s useful to understand the most common styles, which we outline below. We haven’t suggested specific bottles because the availability of certain brands is sporadic. Plus, any given wine changes from year to year.

Champagne is the king of sparkling wines. It’s also expensive and probably best reserved for special occasions. If you do want to get fancy, we recommend using drier Champagnes (no sweeter than brut), which will have flavors of peach, cherries, citrus, almonds, and bread. Common styles are nonvintage (the house’s consistent flagship bottle, aged for a minimum of fifteen months on the lees), blanc de blancs (made only from Chardonnay grapes), blanc de noirs (made only from Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier), rosé (allowing contact with the grape skins for color), vintage (aged a minimum of three years on the lees), and special cuvée (aged for an average of six to seven years on the lees).

Crémant is our go-to sparkling wine for cocktails. Made in similar style to Champagne (though slightly lower age requirements), crémants are made in eight regions of France and can be phenomenally affordable. We prefer Crémant de Bourgogne and Crémant d’Alsace for their similarity to Champagne; using similar grapes grown in a nearby region, these are sparkling wines of incredible complexity. As with Champagne, we steer toward drier styles of crémant.

Cava is Spain’s answer to Champagne, made in the same traditional method as Champagne. The grapes used for cava (Macabeo, Xarello, and Parellada) produce a sparkling wine that has whispers of its French counterpart but an entirely different flavor: fresh apple and pear, lime zest, quince, and just a bit of the almond found in Champagne. There are three quality levels to be aware of: cava is the standard marker, with at least nine months of aging on the lees; reserva spends a minimum of fifteen months aging on the lees; and gran reserva has a minimum of thirty months aging on the lees and vintage dating on the label.

Prosecco is made using the Charmant method, a process where the wine undergoes a secondary fermentation in a large container to create effervescence (as opposed to Champagne or Traditional method, which undergoes secondary fermentation within the bottle). Hailing from the Italian regions of Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia, prosecco has a fresh quality to it: green apple, melon, pear, and even a little dairy creaminess. It comes in three sweetness levels: (brut, extra dry, and dry). The flavor, body, and bubble size of prosecco are quite different from those of sparkling wines made using the traditional method, so we don’t recommend stocking prosecco as your only mixing bubbly; however, it can be a great mixer in traditional Italian aperitif cocktails like the Aperol Spritz (this page), where it acts as a soft supporting player to more powerful ingredients.

Lambrusco is Italy’s other famous sparkling wine, but aside from using the same production method as prosecco, it could hardly be more different. Of the thirteen grape varieties named Lambrusco, the two most planted are Lambrusco Salamino and Lambrusco Grasparossa. The grapes are first made into a sweet, fresh red wine, which is then made into a sparkling wine. Expect strong flavors of strawberry, raspberry, and rhubarb. Lambrusco comes in three sweetness levels: secco (dry), semisecco (off-dry), and dolce or amabile (sweet). We don’t use Lambrusco often in cocktails, but it can add a juicy complexity and slight fizziness to drinks.

The Field Marshall

ALEX DAY, 2013

Riffing on a Champagne Cocktail can be as easy as riffing on any other Old-Fashioned variation. In this case, the sugar is swapped out for a sweet liqueur. Combier is an orange curaçao, and the “royal” bottling has a base of Cognac, which provides a rich backbone. In a way, this variation lies somewhere between a classic Champagne Cocktail and an Old-Fashioned, being made with Armagnac and Champagne instead of whiskey.

1 ounce Tariquet Classique VS Bas-Armagnac

½ ounce Royal Combier

2 dashes Angostura bitters

2 dashes Peychaud’s bitters

Dry Champagne

Garnish: 1 lemon twist

Stir all the ingredients (except the Champagne) over ice, then strain into a chilled flute. Pour in the Champagne, and quickly dip the barspoon into the glass to gently mix the Champagne with the cocktail. Express the lemon twist over the drink, then place it into the drink.

Pretty Wings

DEVON TARBY, 2016

Inspired by famed bartender Dave Kupchinsky’s Lemonade cocktail at the Everleigh in West Hollywood, this drink also looks to the Champagne Cocktail for its simplicity and incorporates flavorful chamomile in an infusion of softly herbaceous and slightly bitter Cocchi Americano. It’s exceedingly refreshing on a hot day.

½ ounce Chamomile-Infused Cocchi Americano (this page)

1 teaspoon Suze

1 dash Bittermens hopped grapefruit bitters

5 ounces Champagne

Garnish: 1 lemon wheel

Stir all the ingredients (except the Champagne) over ice, then strain into a chilled flute. Pour in the Champagne, and quickly dip the barspoon into the glass to gently mix the Champagne with the cocktail. Garnish with the lemon wheel.

Celebrate

DEVON TARBY, 2016

While the components of this cocktail other than the Champagne—take up more volume than a sugar cube doused in bitters, they function in a similar way, enhancing the main spirit by amplifying flavors it already possesses: stone fruit, breadiness, nuttiness, and spice. Here we’ve added a new ingredient, Champagne acid, a combination of tartaric and lactic acid that enhances the tang of a dry Champagne.

½ ounce Clear Creek pear brandy

¼ ounce Lustau Jarana fino sherry

1 teaspoon Fortaleza reposado tequila

¼ ounce Cinnamon Syrup (this page)

½ teaspoon Champagne Acid Solution (this page)

4 ounces dry Champagne

Stir all the ingredients (except the Champagne) over ice, then strain into a chilled flute. Pour in the Champagne and quickly dip the barspoon into the glass to gently mix the Champagne with the cocktail. No garnish.

JULEP

In essence, a Julep is like an especially refreshing Old-Fashioned that substitutes mint for the bitters. Many Southerners will cry foul at this explanation, insisting that the ritual of making a Julep, a sacred heritage below the Mason-Dixon Line, is something Yankees are incapable of understanding.

Be that as it may, we’ll stick our necks out and devote a few extra words to Julep-making technique. Begin by grabbing four or five healthy mint sprigs, enough to create a tight bouquet that spreads to about 4 inches in diameter, and trim the stems to 6 inches. Trim off the lower leaves (hopefully reserving them for another use). Holding an empty Julep tin by the edge (to avoid getting the oils from your hands on the tin, which will prevent frosting), insert the bouquet, upside down, into the Julep tin and lightly rub the leaves against the interior of the tin, using just enough force that you smell mint but not enough to bruise the leaves. Set the mint aside. Add the spirits and sweetener to the tin and stir briefly with a barspoon to combine. Add crushed ice until the tin is about four-fifths full and slowly stir until frost begins to form on the exterior of the tin. Once the tin is frosted, top with a cone of crushed ice and insert a straw along one side. Jiggle the straw in a small circle to create a small channel, then carefully slide the mint bouquet into this channel so that the leaves are tightly bunched together and the sprigs look like they’re growing from the ice.

Mint Julep

CLASSIC

1 mint bouquet

2 ounces Buffalo Trace bourbon

¼ ounce simple syrup (this page)

Rub the interior of a Julep tin with the mint bouquet, then set the mint aside. Add the bourbon and syrup and fill the tin halfway with crushed ice. Holding the tin by the rim, stir, churning the ice as you go, for about 10 seconds. Add more crushed ice to fill the tin about two-thirds full and stir until the tin is completely frosted. Add more ice to form a cone above the rim. Garnish with the mint bouquet and serve with a straw.

EXPERIMENTING WITH OTHER HERBS

Mint is a wonderfully versatile herb for cocktails. It can be incorporated via muddling or steeping, or it can aromatize the top of a drink when it’s used as a garnish. That said, we highly recommend playing with the Julep template by substituting other herbs, whether other mint varieties (such as pineapple mint or chocolate mint) or basil in its many varieties, sage, and even thyme. Keep in mind that some herbs, like certain varieties of sage, can taste off-putting when muddled, and that muddling thyme creates a big mess and doesn’t taste that great. When substituting such herbs, you may want to use them simply as an aromatic garnish, or you might try extracting their flavor through an infusion or syrup instead.

Last One Standing

NATASHA DAVID, 2014

The combination of Cognac and Jamaican rum appears frequently in older cocktail recipes. Here, the duo creates a big, funky core flavor that plays off the bright fruit of the peach liqueur. The amaro acts as a bridge between these two opposing camps, working in much the same way that bitters do, balancing other disparate flavors.

1 mint bouquet

1 ounce Pierre Ferrand 1840 Cognac

½ ounce Hamilton Jamaican pot still gold rum

¾ ounce Amaro CioCiaro

1 teaspoon Giffard Crème de Pêche

Garnish: 1 peach slice and confectioners’ sugar

Rub the interior of a Julep tin with the mint bouquet, then set the mint aside. Add the remaining ingredients and fill the tin halfway with crushed ice. Holding the tin by the rim, stir, churning the ice as you go, for about 10 seconds. Add more crushed ice to fill the tin about two-thirds full and stir until the tin is completely frosted. Add more ice to form a cone above the rim. Garnish with the mint bouquet and peach slice, then lightly dust the top of the mint with confectioners’ sugar. Serve with a straw.

Heritage Julep

ALEX DAY AND DEVON TARBY, 2015

The baked stone fruit and warm autumn flavors of this cocktail make it a great option for an Old-Fashioned lover who’s looking for something on the more refreshing side. We double down on pear, bringing the spirituous heat and pear-like gritty texture thanks to pear brandy and the supple fruitiness of the pear liqueur. The addition of Amaro Montenegro brings this drink into the aperitif category.

1 mint bouquet

1¼ ounces Busnel Pays d’Auge VSOP Calvados

½ ounce Clear Creek pear liqueur

¼ ounce Clear Creek pear brandy

¼ ounce Amaro Montenegro

1 teaspoon Cinnamon Syrup (this page)

2 dashes phosphoric acid solution (see this page)

Garnish: 3 apple slices on a skewer and confectioners’ sugar

Rub the interior of a Julep tin with the mint bouquet, then set the mint aside. Add the remaining ingredients and fill the tin halfway with crushed ice. Holding the tin by the rim, stir, churning the ice as you go, for about 10 seconds. Add more crushed ice to fill the tin about two-thirds full and stir until the tin is completely frosted. Add more ice to form a cone above the rim. Garnish with the mint bouquet and the apple slices, then lightly dust the top of the mint with the confectioners’ sugar. Serve with a straw.

Camellia Julep

DEVON TARBY, 2013

When we use an unaged spirit as the core of a cocktail, we often add other ingredients to mimic the flavors typically contributed by oak and time. Here, we use a clean, straightforward pear distillate that’s been infused with bitter cacao nibs, enhanced with the nut and spice flavors from the amontillado sherry.

1 mint bouquet

1½ ounces Cacao Nib–Infused Pear Brandy (this page)

½ ounce Lustau Los Arcos amontillado sherry

1 teaspoon Demerara Gum Syrup (this page)

Rub the interior of a Julep tin with the mint bouquet, then set the mint aside. Add the remaining ingredients and fill the tin halfway with crushed ice. Holding the tin by the rim, stir, churning the ice as you go, for about 10 seconds. Add more crushed ice to fill the tin about two-thirds full and stir until the tin is completely frosted. Add more ice to form a cone above the rim. Garnish with the mint bouquet and serve with a straw.

Sazerac

CLASSIC

Truly great cocktails become iconic. A Sazerac is such a drink. When you look at the Sazerac’s composition—spirit, sugar, bitters, citrus—it’s so obviously linked to the Old-Fashioned, yet there are differences: While both are served in an Old-Fashioned glass, the Old-Fashioned is served on ice, whereas the Sazerac is served neat. The Old-Fashioned is garnished with twists of citrus in the glass, whereas the Sazerac has a lemon twist expressed over the glass, but the twist is then discarded. Most dramatically, the Sazerac plays a trick on the drinker’s senses: Before the cocktail is poured, the glass is rinsed with absinthe, creating a pungent anise and citrus aroma that persists until the glass is empty—an aroma that contrasts with the cool, boozy liquid below. It’s this technique—rinsing the glass with a highly aromatic spirit—that sets a Sazerac apart and defines it and the variations on it that follow.

The Sazerac also provides a good example of how classic cocktails evolved based on regionally available ingredients. In the mid-1800s, the spirit of choice in Francophilic New Orleans—the Sazerac’s birthplace—was Cognac, but by the end of the century a shortage of French brandy due to a phylloxera outbreak that plagued France’s vineyards shifted the Big Easy’s focus to rye. New Orleans–made Peychaud’s bitters, with its distinctive anise flavor, has remained a constant, but we’ve found that French absinthe and Angostura bitters are welcome additions to the benchmark recipe.

Vieux Pontarlier absinthe

1½ ounces Rittenhouse rye

½ ounce Pierre Ferrand 1840 Cognac

1 teaspoon Demerara Gum Syrup (this page)

4 dashes Peychaud’s bitters

1 dash Angostura bitters

Garnish: 1 lemon twist

Rinse an Old-Fashioned glass with absinthe and dump. Stir the remaining ingredients over ice, then strain into the glass. Express the lemon twist over the drink and discard.

ABSINTHE

In many ways, absinthe and bitters are cut from the same cloth. Just like bitters, absinthe is a highly concentrated flavoring that can be added to cocktails in small quantities as a seasoning, to contribute a bright herbal punch. We sometimes incorporate it by rinsing a glass with absinthe before pouring in the cocktail, a defining technique that sets a Sazerac (this page) apart from an Old-Fashioned. Because of its proof, absinthe clings to the edge of the glass and perfumes the cocktail, creating a unique aroma that complements or contrasts with the cocktail. Absinthe can also be used in small volumes in a drink to create a bright herbal flavor that creates layers of complexity under a cocktail’s core flavor. An example is the Chrysanthemum (this page), where a teaspoon of absinthe enhances the herbaceousness of dry vermouth and the honeyed spices of Bénédictine. We rarely use more than ¼ ounce absinthe in a cocktail, as it can quickly overshadow the core flavor and bully the other ingredients.

There are several styles of absinthe. We prefer Swiss or French styles for their clean flavors. Some of our favorite bottlings are from Pernod, Emile Pernot, and St. George Spirits.

Cut and Paste

ALEX DAY, 2012

Although it’s aged for eight years, the apple brandy in this drink doesn’t taste much like an aged spirit, so we also include pot-distilled Irish whiskey, with its vanilla and spice flavors, in the core. And because Irish whiskey has a nice affinity for honey, we use a honey syrup for the sweetener, which keeps the drink light and crisp, whereas Demerara Gum Syrup would probably be too cloying.

Vieux Pontarlier absinthe

1½ ounces Clear Creek 8-year apple brandy

¾ ounce Redbreast 12-year Irish whiskey

¼ ounce Honey Syrup (this page)

3 dashes Peychaud’s bitters

1 dash Angostura bitters

Rinse a chilled Old-Fashioned glass with absinthe and dump. Stir the remaining ingredients over ice, then strain into the glass. No garnish.

Save Tonight

DEVON TARBY, 2017

In this cocktail, the tart bite of the cherry-infused rye whiskey is complemented by juiciness from the apple brandy, but alone those ingredients would come across as sweet and bland. However, just a couple of dashes of absinthe add an anise pop and complexity to the drink, accenting the tart and juicy flavors in an unexpected way—a great demonstration of the power of the seasoning.

Pernod absinthe

1½ ounces Sour Cherry–Infused Rittenhouse Rye (this page)

½ ounce Clear Creek 2-year apple brandy

1 teaspoon Demerara Gum Syrup (this page)

2 dashes Peychaud’s bitters

2 dashes Pernod absinthe

Garnish: 1 brandied cherry on a skewer

Rinse a chilled Old-Fashioned glass with absinthe and dump. Stir the remaining ingredients over ice, then strain into the glass. Garnish with the cherry.

Bananarac

NATASHA DAVID, 2014

The idea of putting bananas in a boozy cocktail once seemed questionable at best. Then the liqueur company Giffard introduced Banane du Brésil to the US market, a banana liqueur that far exceeded our expectations. When our team first tasted it, we were excited to find it balanced and characterized by a true banana flavor—a rarity in liqueurs. It’s also very versatile. Here, it plays a supporting role, seasoning a boozy drink.

Pernod absinthe

1 ounce Pierre Ferrand 1840 Cognac

1 ounce Old Overholt rye

½ ounce Giffard Banane du Brésil

½ teaspoon Demerara Gum Syrup (this page)

Garnish: 1 lemon twist

Rinse a chilled Old-Fashioned glass with absinthe and dump. Stir the remaining ingredients over ice, then strain into the glass. Express the lemon twist over the drink and discard.

Sherry Cobbler

CLASSIC

Replace the high-proof whiskey in an Old-Fashioned with a larger quantity of low-proof amontillado sherry, and swap muddled orange slices for the bitters, and you have a Cobbler. Amontillado sherry is a fortified wine that gives the cocktail both body and acidity, making it a strong backbone for the drink. When muddled, the orange wheels add not only a touch of sweetness from the flesh but also some seasoning from the bitter pith and the vibrant oils in the skin. This complexity is nicely counterbalanced by the levity and bright aroma of the fresh mint garnish.

When it comes to the garnish, don’t limit yourself to the orange wedge and mint called for here; an array of seasonal fruits is traditional, so play around with whatever fruits or herbs you have on hand. It’s become an inside joke among our bartender friends to make the most ludicrous, overgarnished cobbler any time one of us requests one.

3 orange slices

1 teaspoon Cane Sugar Syrup (this page)

3½ ounces amontillado sherry

Garnish: 1 orange half wheel and 1 mint bouquet

In a Collins glass, muddle the orange slices and syrup. Add the sherry and stir briefly. Top with crushed ice and stir a few times to chill the cocktail. Top with more crushed ice, packing the glass fully. Garnish with the orange half wheel and mint bouquet and serve with a straw.

Traction

DEVON TARBY, 2014

Sherry cobblers were all the rage in nineteenth-century America and we, being obnoxious flag-waving fans of sherry and sherry-based drinks, are happy to keep them in modern rotation. Here, rum shines a light on the dried fruit flavors that are often somewhat hidden in amontillado sherry.

2 lemon wedges

2 strawberry halves

1½ ounces Lustau Los Arcos amontillado sherry

½ ounce Santa Teresa 1796 rum

¾ ounce Milk & Honey House Curaçao (this page)

Garnish: ½ strawberry, 1 lemon wedge, and 1 mint sprig

In a shaker, muddle the lemon wedges and strawberry halves. Add the remaining ingredients and shake with ice. Double strain into an Old-Fashioned glass filled with crushed ice. Garnish with the strawberry half, lemon wedge, and mint sprig and serve with a straw.

Peeping Tomboy

DEVON TARBY, 2017

Almonds and stone fruits, such as apricots, peaches, and plums, are botanically related, and they tend to taste great together in cocktails. Amontillado sherry continues the nutty theme, while Cognac adds a bit of richness and proof. While fresh stone fruit can be a bit inconsistent in terms of sugar and acid, this template is nicely balanced to accommodate fruits of various ripeness.

1 lemon wedge

1 orange wheel

1 slice seasonal stone fruit

1½ ounces Los Arcos amontillado sherry

¼ ounce Pierre Ferrand Ambre Cognac

¼ ounce Toasted Almond–Infused Apricot Liqueur (this page)

1 teaspoon Demerara Gum Syrup (this page)

Garnish: 1 mint sprig, 1 lemon wheel, 1 orange wheel, and 1 slice seasonal stone fruit

In a shaker, muddle the lemon wedge and orange wheel with the syrup. Add the remaining ingredients and whip with a few pieces of crushed ice just until incorporated. Strain into a double Old-Fashioned glass and top with more crushed ice, cresting it over the top of the glass. Garnish with the mint sprig and fruit slices and serve with a straw.

Hot Toddy

CLASSIC

Water is an often overlooked element of cocktails. In our Old-Fashioned, the water comes from a bit of dilution, both while stirring the ingredients over ice and as the chunk of ice in the cocktail melts a bit. A toddy, then, is really just an Old-Fashioned that swaps in hot water for cold. This takes the cocktail in a different direction for two key reasons. First, heat increases the perception of alcohol. If you were to take the same amount of water present in a properly diluted Old-Fashioned—about 1 ounce—and warm it along with the spirit, sweetener, and bitters, you’d have a cocktail with an intensely alcoholic and unpleasant flavor. So for toddies the drink is lengthened. We’ve found that 4 ounces of water to 2 ounces of spirit is a good baseline.

Second, alcohol evaporates when heated, so when you drink a hot toddy, the volatile aromas will rise to your nose before you take your first sip. This can be off-putting if the drink is too high in proof, but it also allows the drink maker to play with aromas, whether infused into a spirit or inherent in it. Calvados, for example, is ethereal when heated, with a warming perfume that’s almost reminiscent of putting on a thick sweater.

Because toddies are both heated and more diluted than other cocktails, they require a bit more sweetener and seasoning than Old-Fashioneds; otherwise, they feel thin. The small amount of lemon juice in the drink doesn’t make it acidic; rather, it helps season the cocktail and bring the other components into harmony.

2 lemon wedges

1½ ounces Elijah Craig Small Batch bourbon

¾ ounce Honey Syrup (this page)

1 dash Angostura bitters

4 ounces boiling water

Garnish: 2 lemon wedges and nutmeg

Squeeze the lemon wedges into a toddy mug, then add the remaining ingredients (except the water). Pour in the boiling water, then grate some nutmeg over the top of the drink and garnish with the lemon wedges.

In Hot Water

BRITTANY FELLS, 2014

If a traditional Hot Toddy isn’t wintry enough for you, try this version, which was developed for the Rose, in chilly Jackson Hole, Wyoming. It evokes a boozy cup of coffee, with the Ristretto bringing dense espresso flavors to the mix, and cardamom-laced bitters offering savory flavors reminiscent of chicory.

1½ ounces Pierre Ferrand 1840 Cognac

¼ ounce Galliano Ristretto

½ ounce dark, robust maple syrup

1 dash Fee Brothers Cardamom bitters

4 ounces boiling water

Garnish: 1 cinnamon stick

Combine all the ingredients (except the water) in a mixing glass and stir. Pour into a toddy mug, then pour in the boiling water. Garnish with the cinnamon stick.

Gun Club Toddy

ALEX DAY, 2012

A toddy is supposed to be soothing, and in this variation we’ve tried to add as many comforting elements as possible. Built on a backbone of Calvados and Pineau des Charentes (an aperitif made from unfermented grape juice and young Cognac), and enhanced with the restorative combination of chamomile, lemon, and honey, this toddy is rich and nurturing.

1½ ounces Chamomile-Infused Calvados (this page)

1 ounce Pineau des Charentes

½ ounce Honey Syrup (this page)

¼ ounce fresh lemon juice

4 ounces boiling water

Garnish: 5 thin apple slices on a skewer

Combine all the ingredients (except the water) in a mixing glass and stir. Pour into a toddy mug, then pour in the boiling water. Garnish with the apple slices.

Heat Miser

DEVON TARBY, KATIE EMMERSON, AND ALEX DAY, 2015

There’s a lot more at play here than in a traditional toddy. The chile-infused bourbon adds gentle heat without making the drink overtly spicy, and bright apple juice stands in for water, adding an extra layer of complexity.

1 ounce Thai Chile–Infused Bourbon (this page)

½ ounce Luxardo Amaro Abano

½ ounce Alexander Jules amontillado sherry

3 ounces fresh Fuji apple juice

1 teaspoon Medlock Ames verjus

½ ounce dark, robust maple syrup

1 drop Salt Solution (this page)

Garnish: 3 thin apple slices on a skewer

Combine all the ingredients in a small saucepan over medium-low heat and cook, stirring occasionally, until steaming hot but not simmering. Pour into a toddy mug and garnish with the apple slices.

MAPLE SYRUP

Real maple syrup is expensive, and for good reason: it’s a pain in the ass to produce. But there’s no substitution for the real thing. We’ve tried a variety of maple syrups in cocktails and found our favorite to be those in the “Grade A Dark Color and Robust Flavor” category. Whereas with honey we seek more subtly, when we choose maple syrup it’s because we want distinctive maple flavor. So while experimenting with lighter styles of maple syrup may yield great results, we’ve found that their subtlety tends to get washed out in cocktails.

Maple syrup’s distinct flavor lends itself to some valuable flavor pairings. Maple loves whiskey, apple brandy, and rum, especially aged molasses rum. But it also has an affinity for herbs such as rosemary and sage, and spices like nutmeg. None of this should be surprising; anything that revolves around fall or winter or taps into a feeling of warmth is probably a good match for maple syrup.

We use maple syrup as is when mixing it into cocktails—no manipulation required.