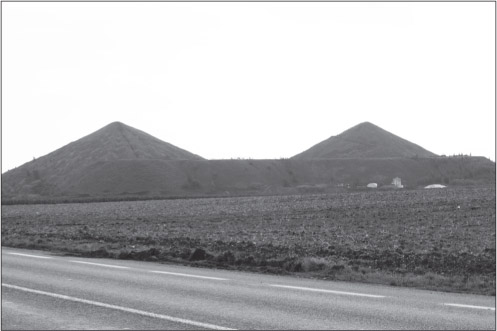

Figure 1.1 The Menin Road, looking up towards the summit of the Gheluvelt Ridge from the village of Gheluvelt. (Authors’ photograph)

On 29 October, 1914, tired remnants of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were on the Menin Road, some five miles to the south-east of the Belgian city of Ypres. They were at a little village called Gheluvelt, defending the slopes of the Gheluvelt Ridge against the might of two German armies, the 4th to the north of the road, and the 6th to the south. Reinforcing these two armies was a special force called Army Group Fabeck, created for the specific purpose of forcing a way through the British defenders to the summit of the Ridge, and the city of Ypres beyond. The British would then have to retreat to the channel ports, and be knocked out of the war. By most peoples’ standards the Gheluvelt Ridge is a gentle slope, and barely worthy of comment, but in the flat countryside of Flanders it represents a significant topographical feature.

The British were exhausted. A lot had happened since the two army infantry corps and one cavalry division making up the small Expeditionary Force had embarked for France from the south of England under cover of darkness on the nights of 12 and 13 August 1914. They had been fighting and marching almost continuously since Sunday 23 August. On that day, on the left flank of the French 5th Army, they had briefly fought the Germans at Mons and along the Mons-Condé Canal, in Belgium, before making a fighting withdrawal to the South on that Sunday evening. On 26 August at Le Cateau, General Smith-Dorrien’s II Corps had turned round to deliver a stinging blow to von Kluck’s German 1st Army, in a manoeuvre designed to slow down the Germans who were hard on the heels of the British forces, and not giving them a moment’s respite.

Figure 1.1 The Menin Road, looking up towards the summit of the Gheluvelt Ridge from the village of Gheluvelt. (Authors’ photograph)

Figure 1.2 Mons and Mons-Condé Canal, with Le Cateau to the south. (Department of Medical Illustration, University of Aberdeen)

The French 5th Army successfully performed a similar manoeuvre against von Bulow’s German 2nd Army at Guise on 29 August, permitting the tired British to have a rest day, and tend to their blistered feet, which ached after constant marching over cobbled streets of northern France in the baking heat of late summer. Then, with their French allies on their right flank, the British pulled back to the River Marne, less than 30 miles due east of Paris. From there, General Joffre, Commander in Chief of the French forces, launched a major counter-offensive against the Germans between 6 and 9 September 1914, in what became known as the Battle of The Marne. He did so with the addition of a new French 6th Army and with the help of the British forces. It was a decisive action, and brought the German war machine to a shuddering standstill, pushing it into reverse. Now it was the Germans’ turn to withdraw, with the French and British in pursuit.

Figure 1.3 The Western Front 1914, also showing the Hindenburg Line (built 1916–17) (Department of Medical Illustration, University of Aberdeen)

The British had marched for more than one hundred and fifty miles since the Battle of Mons, under constant severe pressure, and now at last they had an opportunity to attack. Re-invigorated by the prospect, they and their allies pursued the enemy as they crossed the River Aisne. They had anticipated continuing the pursuit after the crossing, but instead the Germans dug in on the north bank and retreated no further. Another fierce engagement, which would become known as the Battle of the Aisne was fought between 12 and 15 September 1914 and many casualties were sustained. Each side then tried to outflank the other, in a series of moves which became known as the “race to the sea”. Each tried to gain an advantage by getting in behind the enemy forces, and then “rolling up their line”. These outflanking attempts were only brought to a standstill when the opposing armies reached the sandy beaches of the Belgian coast. Soon there were two lines of soldiers facing each other from the Swiss border to the Channel coast, and the Western Front came into being. A war of great movement was about to be replaced by static trench warfare, which would come to characterise the Great War. The advance to the Aisne would be the last piece of open warfare until the spring of 1918.

When troop started to move north in the “race to the sea”, the BEF was transported by train in the general direction of its supply lines to play its part in the unfolding conflict. The original BEF which had fought at Mons on 23 August had two infantry corps in the field, I Corps and II Corps, each with approximately 30,000 men and a cavalry division with approximately 10,000 men. II Corps went north to fight around La Bassée, while I Corps went further north and arrived at the Belgian town of Ypres by mid-October 1914. Reinforcements to meet ever-increasing demands and growing numbers of casualties were arriving as quickly as possible. British III Corps arrived in time for the Battle of The Aisne, and IV Corps in time for the fighting around Ypres in October and November of 1914.

And so it came to be that many British troops found themselves on the Menin Road near Ypres on 29 October. Here the character of the fighting changed dramatically. The Belgian army to the north blocked access to the coastal plain in what became known as the Battle of The (River) Yser, an engagement they only won by opening the dyke sluices and flooding the flat coastal plain from the coast to Dixmuide, thus securing the northern flank of the Allied line for the duration of the war. Here, around Ypres, was the Germans’ last opportunity for a breakthrough, to bring an end to fighting in the West, inflict a defeat on their hated enemy the French and knock the “contemptible” little British Army out of the war. This was to be no outflanking manoeuvre. This was to be a hammer blow of the greatest severity, to punch a hole through the heart of the British defences on the Menin Road. Only then, after first defeating the British, and then the French, would they be able to turn their full attention to deal with the Russian Armies on their Eastern Front.

It was allegedly Kaiser Wilhelm who referred to the British Expeditionary Force as a “contemptible little army”. He probably had meant that it was contemptibly small, which indeed it was, rather than inferring that the soldiers themselves were contemptible. They were in fact a highly trained and hardened professional force, able to fire fifteen aimed rounds a minute using bolt-action Short Magazine Lee-Enfield Rifles. They perhaps performed best in the role of stubborn defence against overwhelming odds, as they were about to prove. There was something symbolically appropriate about the name “Old Contemptible” which the survivors of that small Professional British Army proudly called themselves as 1914 drew to a close.

The British had to call on all their experience to prevent a catastrophic breach of their lines by the Germans. By 31 October, they had been forced to withdraw to the Western, downward slope of the Gheluvelt Ridge, with the city of Ypres to their rear. There they stopped, and there they remained. The Germans never did get into Ypres just two or three miles down the road, and it would be almost four years before the British would re-occupy Gheluvelt.

As a result of this action (which became known as the Battle of Gheluvelt), and other engagements by the British, French and Belgian forces, the Allies came to hold a roughly semi-circular area of ground, bulging out against the German positions with the city of Ypres as a centre point, and with a radius of approximately 4 miles. Thus was born the infamous Ypres Salient. The Germans held the higher ground, on the ridge, and they looked down on the lower and more disadvantageous positions held by the Allies.

A salient is simply a line which protrudes outwards against the enemy position. Fighting in a salient meant that enemy artillery could be sited all round the perimeter, and defenders could be fired at from the front, from the sides, and even from the rear. There were many examples of salients throughout the length of the Western Front, but when men talked about “The Salient”, they invariably referred to the killing zone around Ypres.

Opposing forces spent four years killing and maiming each other in the confined area of The Salient. There were three major engagements around Ypres, which subsequently became classified as battles, although there was fighting here every day for the duration of the war. Even when “nothing of importance” happened, men were killed or wounded in the Salient. The heavy fighting around Ypres in the closing weeks of 1914 became known as the 1st Battle of Ypres and resulted in the formation of the Ypres Salient. British casualties amounted to 58,155 killed, wounded or missing.1 Adding casualties from prior engagements at Mons, Le Cateau, the Marne and the Aisne, it is estimated that by the end of 1914 only 1 officer and 30 other ranks remained of each battalion of 1,000 strong which had gone to France in August 1914.2 The loss of these men was a severe blow, because they were a highly trained force of hardened professionals of great experience. In that sense they were irreplaceable, and it would be a long time before their successors acquired a matching level of ability.

Figure 1.4 Western slope of the Gheluvelt Ridge looking down towards the city of Ypres. (Authors’ photograph)

Figure 1.5 Ypres Salient and Messines Ridge (Department of Medical Illustration, University of Aberdeen)

Figure 1.6 An “Old Contemptible” – he had fought at Mons, Le Cateau, the Marne and 1st Ypres. He died on a day when “nothing of importance” happened on the Western Front. (Authors’ photograph)

There were two other major battles around Ypres. On 22 April 1915, the 2nd Battle of Ypres began when the Germans used poison gas for the first time on the Western Front. Chlorine was discharged from gas cylinders late in the afternoon of the 22nd, between the villages of Poelcapelle and Langemarck, a few miles from Ypres. This resulted in a complete collapse of the northern segment of The Salient, which became saturated by chlorine gas. French colonial troops occupying the trenches here fled, leaving a huge gap. Fortunately, the Germans had made no preparation to fully exploit the advantage gained, and so things were not as bad as they might have been, thanks to the men of the Canadian 1st Division, who had recently arrived on The Salient, and whose quick thinking and rapid deployment saved the day. While this was a crisis for the Allies, they retrieved the situation and The Salient contracted down to a tight defensive position round Ypres, making it easier to defend. The 2nd Battle of Ypres lasted approximately a month and British losses amounted to 59, 275 killed, wounded and missing. This figure includes losses sustained by the Canadian 1st Division and the Indian Corps.3

The 3rd Battle of Ypres began on 31st July 1917. The British strategic aim was to break out from The Salient and capture the Belgian ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge. This would deny their use to the Germans as U-boat bases. This was wishful thinking, and the offensive became completely bogged down in the mud at the village of Passchendaele in November 1917, where men fought and died in the most appalling conditions. This battle involved Australian, New Zealand and Canadian Divisions as well as British and South African troops. Total losses were 244,897 killed, wounded and missing, according to Neillands.4 According to Prior and Wilson the losses were 275,000, with 70,000 killed.5 The reality is that no one knows precisely how many died and sank forever into the mud.

As will be seen in Chapter 2, figures exist for numbers of casualties admitted to, and treated by, the various casualty clearing stations during the 3rd Battle of Ypres. The numbers of wounded are staggering, and one may wonder how on earth the medical services coped with so much work. If a surgical team working in a modern fully equipped hospital of today had more than twenty patients admitted during a 24 hour period, it would consider itself busy. Casualty clearing stations during 3rd Ypres were regularly dealing with 200 to 300 admissions a day, before passing the “on call” on to an adjacent clearing station while working through the caseload of admissions.

More than a quarter of a million British and Commonwealth soldiers died in the confined area of the Salient during four years of the Great War. There are approximately 150 British Military cemeteries within a five-mile radius of the city of Ypres. Some are small and secluded, with only a few dozen burials, while others are huge with several thousand graves. After the war, many tiny cemeteries and isolated graves were relocated to designated “concentration” cemeteries, to allow reclamation of the land. There were dead buried almost everywhere on The Salient, and squads of men searched the battlefield methodically, digging up the scattered dead, and taking them to be reburied in a chosen concentration cemetery. The biggest British military cemetery in the world, and an example of a concentration cemetery, is located near the village of Passchendaele at Tyne Cot, where there are 11,908 graves.

Because of the ravages of time, and the destructive nature of shellfire, 8,366, or 70% of the soldiers (or what remained of the destroyed bodies) buried in Tyne Cot are unidentified. “A Soldier of the Great War Known unto God” was the epitaph given by Imperial author, poet and Nobel Laureate, Rudyard Kipling, whose only son John had been killed at the Battle of Loos in September 1915, and his body never found. The bodies of a great many of those who died were never found, and the Menin Gate at Ypres has the names of 58,000 soldiers who have no known grave inscribed on its stone panels. There wasn’t enough room for all the names here, so a further 34,000 are commemorated on a wall at the back of Tyne Cot British Military Cemetery.

To the south of Ypres, swinging away from the city and towards the nearby French border is Messines Ridge (see Figure 1.5). It was here on 31 October 1914 that the first Territorial battalion to be involved in the Great War went into action. At the same time as the Germans were fighting the British on the Menin Road, they were also trying to get the British off the high ground to the south of Ypres at Messines Ridge. The Expeditionary Force was running severely short of men, and men of the 14th Battalion, County of London Regiment (London Scottish) were rushed into battle on 31 October, 1914 at Wytschaete, in the central part of the Messines Ridge. The London Scottish suffered heavy casualties, in no small part due to the fact that their Lee-Enfield rifles, SMLE Mk 1, were incapable of taking the new Mk VII ammunition. Their rifles jammed unless they were loaded with single rounds fed into the breach by hand, therefore seriously reducing the effectiveness of their weapons.

Figure 1.7 Tyne Cot British Military Cemetery, the biggest British military cemetery in the world. Part of the wall can be seen at the back of the cemetery, inscribed with the names of 34,000 soldiers who died in the “Salient” and who have no known grave. (Authors’ photograph)

The destruction of the small British professional army in late 1914 resulted in Territorial divisions being sent to the Western Front in significant numbers. When the Territorial Force first came into being, the original concept was that it would guard Britain’s shores in the event of the Expeditionary Force having to go overseas. Casualties in 1914 were so heavy that soldiers of the Territorial Army were invited to sign up for posting overseas and when the British took over more of the front line from their French allies in 1915, and their commitment to fighting increased, territorial troops went to France in increasing numbers, partly as battalions to reinforce depleted divisions already in France, and partly as entire divisions to take part in British offensives of 1915.

In addition to having to defend on the Ypres Salient in April and May 1915, the British conducted offensives between March and September in northern France at Neuve Chapelle, Aubers Ridge, Festubert, and Loos, all very much at the instigation of their French allies who wanted British support while they (the French) attacked the Germans further south.

Figure 1.8 The 1915 battlefields in Northern France. (Department of Medical Illustration, University of Aberdeen)

By April 1915, there were six Territorial divisions in France, the 46th (North Midland), 47th (London), 48th (South Midland), 49th (West Riding), 50th (Northumbrian), and 51st (Highland).6

The first of Kitchener’s Volunteer divisions had also arrived on the Western Front by 1915, and they were to play a major part in the fighting over the next two years. Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, had little faith in the Territorial Army, harbouring a quite illogical prejudice against it. Kitchener was one of the few who did not believe that this war would be “over by Christmas.” Realising that it would be a long and costly conflict, he instigated a recruiting campaign to persuade men to volunteer for service in the British Army. Posters appeared with Kitchener’s stern face and pointing finger, challenging whoever stopped to look to join up. Men flocked in their thousands to enlist. Two of the first resulting service divisions of Kitchener’s “New Army” were in the field by mid 1915, in time to take part on the first day of the Battle of Loos on the 25th September 1915. It just so happened they were both Scottish Divisions. The 9th (Scottish) and 15th (Scottish) Divisions were two of a total of six divisions which went over the top and into battle on 25 September 1915. Men forming these two divisions came from all over Scotland, as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

Scottish battalions in the 9th and 15th Scottish divisions at Loos, 25 September 1915

Based on Ewing, J., The History of the 9th (Scottish) Division 1914-1919. London: John Murray, 1921, p.398 and Stewart, J. & J. Buchan, The 15th (Scottish) Division 1914-1919. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1926, pp.286-7.

An infantry division was made up of 3 brigades, and each brigade had 4 battalions. At full strength there were nearly 1,000 men in each battalion. Thus each division had approximately 12,000 infantry, and the two Scottish divisions, in battle for the first time, sustained appalling casualties. The respective statistics for casualty figures are taken from their divisional histories7,8, and are summarised in Table 1.2. The figures shown refer to losses sustained over three days between 25 and 27 September, 1915.

Table 1.2

Casualty figures for the 9th and 15th (Scottish) divisions at Loos, September 1915

| Division | Officers killed, wounded, missing | Other Ranks killed, wounded, missing |

| 9th (Scottish) | 190 | 5,867 |

| 15th (Scottish) | 217 | 6,406 |

Based on Ewing, J., The History of the 9th (Scottish) Division 1914-1919. London: John Murray, 1921, p.398 and Stewart, J. & J. Buchan, The 15th (Scottish) Division 1914-1919. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1926, pp.286-7.

Figure 1.9 The “Double Crassier” marking the southern limit of the battlefield at Loos, so typical of this industrial region of Northern France. (Authors’ photograph)

Figure 1.10 The battlefield at Loos looking north towards La Bassée. The northern limit of the battlefield was the La Bassée canal. The town of La Bassée was behind the German lines. (Authors’ photograph)

Indeed, the Battle of Loos can justifiably be described as “a very Scottish battle”, because in addition to the 9th and 15th Divisions, there were Scottish battalions in the three regular divisions that took part at Loos. The Battle of Loos was fought over ground which was partly industrialised, with slag heaps called crassiers, from coal mines, and partly over flat and featureless open country with no natural cover.

The battle was fought against the better judgement of the High Command, who were pressurised into supporting French offensives further to the south at Vimy Ridge and Champagne. Because of a severe shortage of artillery pieces and ordnance, reliance was placed on poison gas to compensate for these deficiencies. It was the only occasion during the war that a battle was fought relying strategically on gas rather than artillery to procure a successful outcome. It failed miserably. The wind such as it was, was blowing in the wrong direction over much of the battlefield, so that on the front of the 1st Division men became victims of their own gas.

It would be at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, however, when Kitchener’s Volunteers would be present in a majority of participating divisions on the first day of battle.

The Somme will forever be associated with heavy and tragic loss. The 1st July 1916 was in absolute terms to be the worst ever day in British military history as Table 1.3 only too clearly illustrates.9

Table 1.3

Summary of losses at the Battle of the Somme, 1 July-mid-November 1916

| Total casualties 1 July | 60,000 |

| Killed in action 1 July | 20,000 |

| Total losses 1 July-mid November | 432,000 |

| Killed in action or died of wounds 1 July-mid-November | 150,000 |

By 1915, volunteers were diminishing in number significantly, and men had to be found to maintain battalion strength in the face of ever mounting casualties. By late 1915, all men between the ages of 15 and 65 years who were not already in the forces had to register to notify the authorities which trade they were in. In October 1915 Lord Derby was appointed to the position of Director of Recruiting. He then proceeded to encourage all those between the ages of 18 and 40 to either enlist or to attest with an obligation to enlist if called. The carrot to encourage enlistment, if it can be called that, was the assurance of a war pension in the event of being killed or wounded. Not surprisingly, this encouragement did not have the desired result, and consequently conscription was brought into effect in the Military Services Act in January 1916.

Many recruits from the Derby Scheme or young conscripts would first see action in 1917. The two principal battles in 1917 were the Battle of Arras, in April and May 1917, and 3rd Ypres, from the 31st July to the 10th November 1917. Losses at Arras were approximately 158,660, of whom 29,505 were killed.10 Losses at 3rd Ypres have already been mentioned. By mid-1917 therefore, until the end of the war, the ever-expanding British Army, excluding those from the Dominions, would be a mixture of remnants of the original British Expeditionary Force, men from the Territorial Army, Kitchener’s Volunteers and conscripts.

The Germans too were feeling the strain. They suffered very severe losses in 1916, both on the Somme and at Verdun, where they had fought a prolonged battle of attrition against the French from February to December 1916. As a result of losses sustained in these two battles, they withdrew to a prepared defensive line which effectively shortened the length of their front by eliminating a broad-based salient. This was called the Hindenburg Line by the British.

Beginning on 21 March 1918, the Allies had to withstand a series of five German offensives launched from the Hindenburg Line, between March and July, as they desperately tried to bring the war to a conclusion. In February 1917, the Germans had introduced unrestricted U-boat activity against neutral merchant ships supplying the allies, resulting in the sinking of American ships. This proved to be the last straw, bringing the United States of America into the war in April 1917. It would be many months before Americans would be fighting in France, but the German High Command knew that ultimately they would bring in overwhelming numbers of men with appropriate materials from their almost unlimited resources. On the 16th December 1917 the leaders of the Bolsheviks – Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin – sued for peace with the Central Powers, and an armistice was declared. A peace treaty was signed on 29 March 1918 at Brest-Litovsk, and Russia was out of the war.

Massive numbers of German troops moved from what had been the Eastern Front across to the Western Front in preparation for major offensives in the spring of 1918. The aim was simple – to end the war before overwhelming numbers of Americans arrived and brought about the inevitable defeat of Germany. Mobile warfare was back to stay, and the British were pushed back to the very outskirts of Amiens before the first of the German offensives, codenamed “Michael”, was halted. There followed a further four offensives, one against the British in the north, pushing up through Armentières and Messines Ridge from the south towards Ypres and the railway junction of Hazebrouck, and three against the French around Rheims. While much ground was lost to the enemy in these offensives, the Allied lines were never breached, and the attacks petered out. The German gamble had failed, and they had effectively lost the war, although it still had a long way to run.

On 8 August 1918 the British launched a major counter-offensive at the Battle of Amiens, and after 100 days of crushing victories, the war was over. Men who had gone to war in the warm summer of 1914 would not have recognised the army of 1918. It had been transformed by sophisticated artillery, able to locate German batteries accurately by sound ranging, and by new high explosive shells which were the equivalent of a modern day cruise missile by comparison with what had been available in 1914. Infantry attacks went in behind scientifically calculated creeping barrages to protect the advancing troops, and by late 1918 the British Army had become an unstoppable force.

Losses however were still very heavy. The official figures for battle losses in 1918 on the Western Front are shown in Table 1.4.11 The very large number of prisoners of war reflects the rapid gain of ground made by the Germans during their Spring Offensives, when they made huge inroads, advancing many miles, and capturing many demoralised and confused troops. The Germans of course experienced a similar pattern of losses during the last hundred days. In 1913, before the outbreak of the war, the approximate total strength of the British Army at home and overseas was 212,355. By 1918, that number was 4,796,088.12

Table 1.4

Battle casualties 1918

(Modified from Mitchell, T.J. & G.M. Smith, History of the Great War based on Official Documents. Medical Services. Casualties and Medical Statistics. London: HMSO, 1931, p.168)

The maintenance of health, prevention of disease and the provision of medical care to wounded military personnel, from the battlefield to complex modern hospitals during times of conflict are essential in any military force. Historically, the first medical officers were appointed to the army of Charles II with the position of Regimental Surgeons. Each was provided with an assistant surgeon and a basic hospital facility. However, it was in 1812 that the first attempt was made to organise a medical service when the Duke of Wellington and his men were fighting the armies of Napoleon in Spain and Portugal. The Chief of Medical Staff for Wellington’s army was Sir James McGrigor, a graduate of the University of Aberdeen13, who went on to become Director-General of the Army Medical Services between 1815 and 1851. He is regarded as the father of army medical services.

During the long interval of peace between the final defeat of Bonaparte in 1815 and the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1854, many of the medical lessons learned during the Napoleonic Wars were lost, which partly explains the dismal performance of the medical services during the Crimean War.

Another important factor contributing to this unsatisfactory state of affairs was the lack of authority and low status which was accorded to doctors. They were regarded as little better than camp followers. Doctors did not have a military rank. They did have some, but not all, of the privileges that would have gone with rank. Whilst provision of servants, living accommodation, financial compensation for wounds and pensions for doctors and their families were comparable to those of other officers, they usually received less pay. As a result of this inequality, there was much unrest and dissatisfaction amongst army doctors which led to considerable debate in the medical press. Some expressed the view that military rank was unnecessary and had no meaning for a doctor. His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge went further and argued that his “military instincts could not carry the idea of giving medical officers military titles or rank”.14 Others thought that the lack of military rank could result in doctors having disciplinary problems with soldiers in hospitals.

Each regiment had a surgeon and assistant. Whilst there was an overarching Army Medical Department, there was a lack of coordination and cohesion in the provision of services. Their low status and lack of authority within the overall army structure meant that doctors could not play any part in driving the medical agenda for the benefit and well being of soldiers. His low status meant that a medical officer was not even permitted to dine with other officers. All these factors combined to foster feelings of great resentment and discontent.

The Crimean War was a major disaster in terms of medical care of the wounded and the sick. The provision of drinking water and the disposal of sewage were inadequate. Drinking water was contaminated by harmful bacteria, and communicable disease was rife amongst the soldiers who lived in cramped and unhygienic conditions. Many more soldiers died from disease than succumbed from wounds. The figures for the Crimean War are shown in Table 1.5 where five times as many men died from disease (predominantly cholera and typhus in British, French and Russian troops with French troops also dying from scurvy). In subsequent wars, this ratio decreased, although even by the Boer War (1899-1902), typhoid fever killed many more British troops than enemy action (see Chapter 2). It would not be until 1914-1918 that deaths from wounds would greatly exceed deaths from disease, and that state of affairs would only come about after a major shift in policy regarding the role of doctors in the planning and provision of health care amongst soldiers.

Florence Nightingale worked in a military hospital at Scutari, near Istanbul, arriving there in November 1854. She found wounded soldiers being badly cared for by overworked medical staff in appalling conditions and in the face of official indifference. She quickly and inevitably came into conflict with Sir John Hall, the head of army medical services in the Crimea, who described her as a “petticoat imperieuse” since she was fiercely critical of him and of the hospital facilities.

Table 1.5

Deaths from those with wounds and from those with disease in different wars

| War | Years | Ratio of deaths due to disease compared with that due to wounds |

Peninsular War |

1808-1814 |

7.5:1 |

Florence Nightingale believed that the high death rates were due to poor nutrition and exhaustion of the soldiers, and this point of view brought her into conflict with another strong-willed and uncompromising figure, Dr. James Barry.

Barry was a graduate from the University of Edinburgh, who had a great interest in the role that nutrition, exercise, hygiene and sanitation played in the maintenance of good health. He was a skilled surgeon, and is credited with performing one of the first caesarean sections in South Africa when both mother and child survived in around 1820. He attracted controversy, and was recognised as being opinionated and argumentative, and he displayed lack of respect for military regulations. It is said that he spoke with a high-pitched voice and was “effeminate”. He was inclined to seek confrontation with his military superiors and although frequently reprimanded he continued with his work regardless.

At the outbreak of the Crimean War, Barry had been posted to nearby Corfu, where many of the wounded were treated. Indeed, Barry’s method of nursing sick and wounded soldiers evacuated from the Crimea was so successful that the recovery rate was the highest for the whole Crimea campaign. Hearing of events in Scutari, Barry applied to go there. His application was ignored, but Barry decided he was going anyway, and this brought him into conflict with Florence Nightingale. These two strong-minded individuals did not get on well together. There was a public confrontation. Barry believed that disease was caused by poor hospital sanitation and bad ventilation. He left Florence Nightingale in no doubt that poor hygiene was the cause of disease and that she had not addressed the problem. Barry scolded Nightingale for her unclean practices. She responded strongly, and in her words, Barry was “a brute” and “the most hardened creature I ever met throughout the army”. Many years later after Barry’s death in 1865, she said:

As Mr. Whitehead once remarked, I will mention that I never had such a blackguard rating in all my life – I who have had more than any woman – than from this Barrie sitting on (her) horse, while I was crossing the Hospital Square, with only my cap on, in the sun. (He) kept me standing in the midst of quite a crowd of soldiers, commissariat servants, camp followers, etc., etc., everyone of whom behaved like a gentleman during the scolding I received, while (she) behaved like a brute. After (she) was dead, I was told (he) was a woman.15

A Sanitary Commission was sent out to inspect the hospital facilities in Scutari, flushed out the sewers in the hospital, and improved ventilation, as a result of which death rates from infectious diseases fell dramatically with Nightingale’s help.16

It seems unfortunate that two such single-minded individuals as James Barry and Florence Nightingale did not see “eye to eye”. They were both determined to improve matters, and although they held different views as to the cause of the high mortality amongst troops they were both on the right lines for tackling the same problem from their respective approaches. Had they combined their skills, instead of being at loggerheads, the outcome for many soldiers might have been more favourable.

After the Crimean War they both returned to England, but there was a twist in the tale. Nightingale received praise and was recognised for the remarkable reduction in deaths due to infectious disease, and she continued to work tirelessly for health reforms.17 Such praise and fame probably had an element of “Victorian spin,” focusing public attention on the “lady with the lamp,” while at the same time diverting the nation’s focus away from the awful and embarrassing reality of the Crimean War. By way of contrast Barry was forced to retire from the army against his will in 1859. He died six years later from influenza, with very little money and in relative obscurity. After his death in 1885, despite having left strict instructions to be buried in the clothes in which he died and for there to be no post-mortem, it was revealed that he was a woman, and may even have had a child as evidence by striae gravidarum (stretch marks) on his abdomen. However, this can happen in males also if they have certain types of hormonal disturbance, e.g. Cushing’s disease.

Barry’s life is still the subject of mystery, and rumours of affairs with nobility persist – there are more questions than answers concerning this doctor.18 However, Barry had lived life as a male to be able to pursue an ambition to enter medical school, had studied surgery and had made a major contribution to health in general and military surgery in particular. Perhaps James Barry could lay claim to being the University of Edinburgh’s first female graduate and the first female from Britain to become a doctor.

Figure 1.12 Plaque commemorating James Barry, Old College, University of Edinburgh. (Authors’ photograph)

Following the medical disaster of the Crimean War, a Royal Commission was set up in 1857 to look at the various problems, very much at the instigation of the British Medical Association and Florence Nightingale. It highlighted problems associated with poor sanitation, and ways of dealing with the sick and the wounded. It addressed the problems of poor medical training, and inadequate surgical experience displayed by doctors in the Crimea. It made a number of suggestions, such as the formation of an army medical school, and that medical officers should be given authority to give advice to commanding officers on matters relating to the health and well-being of the troops.

The Army Medical School was opened at Fort Pitt in 1860, moving to Netley, near Southampton, in 1863. Netley was close to, and within easy access of the port of Southampton, where hospital ships arrived, and was specifically intended for the reception and treatment of returning wounded soldiers. The site had been bought for the sum of £15,000 and Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone in 1856, beneath which were laid the plans of the hospital, the first Victoria Cross to be made and a silver Crimea Medal. When the hospital was demolished in 1966 the Victoria Cross was retrieved from beneath the foundation stone. It may now be found in the Army Medical Services Museum and is called “The Netley VC”.

There were many faults with the hospital at Netley, such as lack of ventilation, and the Army medical school was subsequently moved to Millbank in London in 1907 (via temporary accommodation in London in 1902). Netley continued to function as a hospital for many years, being used by the USA in the Second World War as such. Millbank was not only a place for doctors to be trained but it also functioned as a research centre, pushing forward the frontiers of military medicine and surgery.

For a doctor to join the army in addition to being qualified in medicine, he had to be unmarried, have dissected a whole body, and observed 12 midwifery cases. Then he had to be successful in a further series of examinations including meteorology, geography, zoology, botany and not forgetting of course, medicine and surgery!

The report of the 1857 Royal Commission led to the Warrant of 1858, which introduced the first elaborate code for the medical services, but still left it weak. While it ensured that doctors now had a rank, albeit a combined medical/military one, and pay and conditions became equivalent to non-medical officers, the new combination rank (e.g. “surgeon captain”) was not generally accepted by non-medical officers. The medical department was rarely consulted on matters relating to health. Medical officers spent all their time with their regiments, and had little opportunity to improve their knowledge. They were regarded exclusively as “treaters of disease.” There were even separate regimental hospitals, and however many regiments were in a garrison, each had its own facilities, which was hopelessly inefficient.

In 1873, the regimental hospital system was abolished, and replaced by garrison establishments complete with laboratories, libraries, and expert instruction, which was at least a step in the right direction. This change was opposed by many senior officers, who were then granted the concession of retaining the services of a particular medical officer for ten years. Thus different battalions were cared for in different wards but all under the same roof. At least this “centralisation of services” created the potential for a coordinated medical plan for the first time in the event of a war.

Heavy casualties in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 led to the establishment of a system with a regimental medical officer and a team of sixteen stretcher-bearers, based on the Prussian model, for early treatment of the wounded.

Nevertheless, while all this was happening, a life in the army was not an attractive proposition, with little perceived benefit compared with civilian practice. Recruitment continued to be difficult. Whilst conditions for medical officers may have appeared to have changed for the better, in practice nothing had altered. Army doctors were still held in low esteem, and were regarded in the same way as before. The opportunities and benefits of working in a civilian practice far outweighed those of being in the army, both in terms of status and financial remuneration.

In 1884, the medical military ranks, such as they were, e.g. “surgeon major”, were abolished, and there was much bad feeling between the medical profession and the War Office. Most medical schools refused to supply candidates for the Army, and there was a great deal of lobbying by the British Medical Association (BMA) to bring about change. The medical Royal Colleges, whilst not supportive of army careers for doctors, did emphasise that army doctors should have equivalent military rank to non-medical officers, to enable them to carry out their duties with appropriate authority. However, resistance to doctors having equivalent military rank persisted, both from the War Office and other military personnel. In spite of this, there was growing awareness within the army of the difficulties faced by doctors and an appreciation of the issues which had to be addressed to allow provision of better medical care.

Even so, things did not improve. There were no new doctors taken into the army in the two years after 1887. A parliamentary committee reported on doctors’ injustices in 1890, while the campaign for equality for medical officers continued, with lobbying by the BMA and Royal College of Physicians.

By now even peace time requirements for army medical personnel were not met. Only after a long and bitter struggle did commonsense prevail, and in 1898, out of struggle and strife, the Royal Army Medical Corps was born. “In Arduis Fidelis” (Steadfast in Adversity) is their motto, and how appropriate!

Officers and other ranks providing medical care became the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). The first Colonel–in-Chief was HRH the Duke of Connaught, who would later become Governor General of Canada, and whose daughter, the Princess Patricia, would become Colonel-in-Chief of The Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, the first Canadian troops to set foot in France during the Great War.

In spite of the creation of the RAMC, inequality persisted, and doctors did not see joining the army as an attractive career option. Not only were there no new doctors joining but there continued to be a boycott by many medical schools for a variety of reasons, including the uncertainty about careers within the army. Army doctors had to retire after 10 years service, and they did not have the same conditions governing leave as other officers.19

During the Boer War, mortality from infectious disease, especially typhoid fever, significantly exceeded deaths sustained during fighting. Medical officers still had little “clout” in managing health issues, while the higher command regarded such matters as beneath their dignity.

A key figure in the development of the RAMC, and in bringing about a change in the medical officer’s standing, was Sir Alfred Keogh, who had joined the Army medical services in 1880. Keogh was a doctor of exceptional ability, gaining the highest marks during his time at the Army Medical College. As his career developed, he distinguished himself in the Boer War and rose rapidly through the ranks, becoming Director-General Army Medical Services in 1904. Medical officers had experienced difficulties with other officers during the Boer War, who showed lack of respect for their commitment and professional skills. There was a suggestion that the Victoria Cross should not be awarded to doctors (no matter what their acts of bravery) and their terms and conditions were still not equivalent and appropriate. This situation could not be allowed to continue and another Royal Commission was set up to make recommendations to bring about the necessary changes to put an end to this long-standing inequality.

Alfred Keogh made important contributions in the RAMC to improvements in hygiene and to the reorganisation of the service during his tenure of this post until his initial retirement from the army in 1910.19, 20 Poor hygiene and communicable diseases had been a cause of substantial morbidity and mortality during the Boer War. The Army School of Hygiene was established by Lt-Col Richard Firth. As Professor of Hygiene, he particularly addressed such issues as good sanitation, clean water supplies (chlorination), effective typhoid vaccine, and the education of soldiers in matters pertaining to their health and well-being. These measures were vital to ensure that the problems resulting from poor hygiene in the Boer War were not repeated in the Great War. Keogh ensured that different hospitals in existence were reorganised to create larger, fit for purpose military hospitals where appropriate expertise and facilities for treating the wounded was to be found.21, 22

In 1906, Richard Haldane was appointed Secretary of State for War, with a remit to modernise the British Army in preparation for a European war. He was arguably the most capable Secretary of State for War that Great Britain has known, and his achievements are discussed in detail in Chapter 2. Like any politician, Haldane was very aware of financial restraints. He knew that the army had lost too many men to various preventable diseases in previous campaigns. It was very much in his interest to ensure that the soldiers received the best possible medical care, minimising losses from disease, and maximising the fighting capability of the troops. In Alfred Keogh, he found a very supportive ally, and at long last, medical officers were to play a significant role in the health and well-being of their charges, with due attention being given to proper sanitation and appropriate education of medical personnel.

While Haldane was creating the Territorial Force, Keogh was instrumental in the development of sanitary companies in that Force, and he keenly supported the Territorial hospitals, which he saw as a key component of the provision of medical care in time of war or disaster. Needless to say, he was given every support necessary by his political ally to make all this happen.

However, there was still a problem with the number of medical officers. It was recognised that in the event of war there was an insufficient number to service an expeditionary force. To deal with this, an additional 179 medical officer posts were created.23 The work of Haldane in planning the reorganisation of the non-regular army into Special Reserve and the Territorial Force and the Officer Training Corps provided a framework upon which Keogh could develop the medical systems. Keogh used his initiative in recruiting medical officers, going around the country to meet and consult with civilian doctors who were interested in, and understood the requirements for medicine as practiced in the army. He listened to their advice and acted upon it. His endeavours were successful, because Territorial medical units rapidly became established and by 1910 had full or near-full complements of doctors. During his tenure he actively worked with medical schools to provide a reserve of doctors who would be called upon in time of war. The Officer Training Corps (another of Haldane’s reforms) was established in the Universities with the intention of encouraging an army career. This was very successful because almost 2,000 medical students gained military experience through the Officer Training Corps before the start of the Great War.

Although Keogh had retired from the army in 1910 he was recalled in October 1914 and played an important role in the Great War, taking up the post of Director-General Army Medical Services in the War Office. His work and planning formed the basis of the rapid mobilisation of Territorial hospitals at the start of the Great War and they worked with the regular hospitals very effectively. On the Western front, Sir Arthur Sloggett became Director General Medical Services (DGMS), which split responsibilities to make a manageable workload for both of these men. Interestingly, Sloggett had been at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898, had been shot through the chest, and was thought to have been killed. A closer inspection revealed that he was still alive. He was “revived”, by whatever means, and survived the experience, going on to achieve great things!

At the outbreak of the Great War there was an estimated need for 800 medical officers to be attached to the British Expeditionary Force. The available doctors to the entire British Army at that time were as follows:24

• 406 regular army medical officers

• 119 reserve list medical officers

• 248 special reserve medical officers

In order to increase the number to the desired level, and acknowledging the need to increase numbers over and above the immediate requirements, the Central Medical War Committee in England and Wales conducted a recruiting campaign for civilian doctors. In Scotland, a Scottish Medical Service Committee had already been set up and was responding well to the needs of the military, while ensuring that the medical requirements of the civilian population were being met. Both these committees were successful and initially more than 5,000 civilian doctors were enrolled. It was planned that medical officers would stay with the army for either 12 months or until the end of the war.

Perhaps of some concern was the fact that more than 2,000 doctors had been in the Territorial and reserve units and were not available for practices in the UK. Various measures were employed to reduce the impact on the civilian population, these being of some assistance. Territorial medical officers would be kept close to their practices, exchange with other doctors or stay in a home-based unit if the unit they had been with was sent overseas. However, in many situations doctors were removed from their practices to serve and with a lack of time to sort out their civilian practices before leaving.

By the beginning of the war the required number of doctors for posting overseas had been reached and there seemed few concerns about having sufficient numbers for the war effort. That said, the medical profession itself questioned the need for so many. There were financial implications associated with joining up, with loss of income from leaving lucrative civilian practices. Furthermore, the costs of getting a locum to look after practices could be high and act as a disincentive. Attempts were made at a national level to prevent doctors who stayed at home from benefiting financially. Not only were army doctors required for overseas but fighting units still at home in the UK required an adequate number of doctors who had many tasks to ensure the maintenance of optimal health amongst their men.

A medical officer had two responsibilities. One was to the individual soldier, and the other was to the army and nation. His responsibility to the soldier was to ensure that he provided the best possible treatment in the event of that soldier being wounded, and do his utmost to save his life and mitigate his suffering. His responsibility to the army was to ensure minimum wastage of manpower. He had a duty to make a soldier fit again as quickly as possible after being wounded, and to prevent the spread of disease in a force, thereby minimising losses through disease and illness. One of the principal duties of medical officers in the forward areas was to retain soldiers with minor wounds in the forward area, preventing their loss to base hospitals and delaying their return to the front line.

The war situation was changing all the time. Large numbers of wounded on the Western Front, conflicts in other theatres of war, and the deaths of many doctors, led to a re-evaluation of the situation. It was realised by the end of 1915 that although about 25% of all doctors in the UK had already joined the army, there was going to be a shortfall. Another 100 doctors would be needed by the start of 1916. A variety of measures were adopted to allow doctors to leave their practices without disadvantaging themselves or their civilian patients. In spite of this, and in spite of increasing numbers of medical personnel from other combatant nations, there were still not enough doctors.

Lord Derby’s scheme (the 17th Earl, Edward Stanley), which was started in 1915 to provide manpower for the war effort was also applied to doctors. Those doctors who volunteered for service would only be called when necessary, and those who were married would only be asked to serve in the absence of available single men. The Derby scheme was not a successful exercise, and led to the Military Service Act, 1916, which meant that doctors also were liable for conscription. There was still the problem to ensure that whilst there were adequate numbers for the ever-increasing demand of the military, there were sufficient doctors for the civilian population. To achieve this balance, and to decide where doctors would be of most use, the Central Medical War Committee, the Scottish Medical Service Committee and a Committee of Reference composed by the Medical Royal Colleges would make the necessary decision.25

By the later stages of the war, in the regular and Territorial Forces there were more than 12,000 medical officers and the age at which they could be called up had increased to 55 years. The official figures for the number of medical officers in 1914 and for 1918 are shown below, and reflect a striking increase in numbers to meet military demands:26

• Strength of RAMC in August 1914 – 1,279 officers and 3,811 other ranks

• Strength of Territorial Force in August 1914 – 1,889 officers and 12,520 other ranks

• Strength of RAMC in August 1918 – 10,178 officers and 100,176 other ranks

• Strength of Territorial Force in August 1918 – 2,885 officers and 30,923 other ranks

In September 1914, the Director-General of Army Medical Services, Sir Alfred Keogh, adopted the idea of gathering medical statistics which would document the scale of the problem and provide information from which appropriate plans could be made and might also allow development of better medical care. The Medical Research Committee (now the Medical Research Council) offered the services of their statistical staff to collect data (really for planning for future conflicts), and this offer was accepted by the Army Council on 17 November 1914.27 The original undertaking was based on the assumption that the war would be short. The sheer magnitude of the Great War meant that all existing methods of record keeping fell short of what was required for complete success, and so consequently data collection was not always accurate. With huge numbers of troops in different parts of the world, and with forces in many theatres of war constantly moving, it proved very difficult to keep track of things. An index card system was employed as a record keeping mechanism.

These index cards were kept officially by stationary and general hospitals. After every six months, the cards were sent to the statistical department of the Medical Research Committee, to be used at the end of the war as data for statistics relating to medical aspects of the conflict. Mistakes were very common, however, because fighting units were very often scattered over a wide and constantly moving area in distant theatres of war. Frequently the wrong cards got sent to the wrong units, and by the time it all got sorted out, the units had often moved on. The result was that only the British Expeditionary Force in France kept records of any value. In other forces, the cards were either not used, or, if used, were of little value. The shortcoming of the medical statistics will be illustrated in the course of subsequent chapters.27

Casualties were either battle casualties when caused by enemy action, or non-battle casualties when caused by injury or disease. This book is about the surgery of warfare, so it will deal almost exclusively with battle casualties, although a brief mention of non-battle casualties, particularly from the important perspective of preventative medicine, will be made in Chapter 2.

Battle casualties were sub-divided into temporary and permanent “losses”. Reference to Table 1.4 will demonstrate this point. Death is an extreme example of permanent loss. Other examples of permanent loss, as far as the army was concerned, were those who were missing, and those who were prisoners of war. From a military standpoint, it did not matter whether soldiers had been killed, were missing, or had been taken prisoner. If they were not able to stand in a trench with a rifle at the ready, then they were of no use to the army. Obviously, these three categories of permanent losses did not come under medical care. They constitute 26.19% of all battle casualties.28

It was how the medical services dealt with non-permanent losses that would determine how they were judged. Between 1914 and 1918, the medical services in France and Flanders dealt with 1,989,969 battle casualties.29 Of the 1,989,969 battle casualties who reached the medical services, 151,356 or 7.6% died.29 Most of the discussion in the following chapters will relate to developments in surgery in France and Flanders. Contemporary medical literature deals predominantly with wounds sustained on the Western Front.

In absolute terms, the number of troops engaged, and consequently volume of work and surgical experience gained by those medical personnel working on the Western Front, was greater than in other theatres of war. The close geographical proximity of the Western Front to the United Kingdom meant the easy transfer of medical personnel and medical correspondence backwards and forwards between hospitals in the United Kingdom and the base hospitals and casualty clearing stations in France and Flanders. Consequently, it was in the casualty clearing stations in France and Flanders where most surgical progress was made. Only data from France and Flanders was of a reasonably reliable quality, while communications with personnel working in distant theatres was more difficult and data collection much less reliable. The percentage deaths of wounded and of those dying of disease in various theatres of war are illustrated in Table 1.6.30

Table 1.6

Deaths from those with wounds and from those with injury or disease

Modified from Mitchell, T.J. & G.M. Smith, History of the Great War based on Official Documents. Medical Services. Casualties and Medical Statistics. London: HMSO, 1931, p.16.

The percentage of soldiers who died after being admitted suffering from disease on the Western Front was low at 0.91% of admissions. As might be expected the percentages of soldiers dying from disease was higher in Mesopotamia, the Dardanelles and East Africa where they were exposed to tropical diseases and dysentery. Nevertheless, when one compares this with the percentage mortality of 3.39% of the sick admitted during the Boer War, the percentage figures for the Great War, even in “unhealthy” locations, compare favourably

One figure which really stands apart and is difficult to explain is the very low percentage of deaths from wounds in the Italian campaign at 1.22%, compared with 7.61% on the Western front. The total percentage of battle casualties killed in action was 14.7%31 on the Western Front, while in Italy that figure was 19.46%32, suggesting that perhaps the pattern of wounding was different, more being killed outright, and those surviving perhaps not having such serious life-threatening wounds. On the other hand, one must return to the question of reliability of data, and it may simply be that data collection was poor, and the figure may be misleading. “There are lies, damned lies and statistics!”

There is no doubt, as will become clear in the following chapters, that the medical services were caught off balance at the start of the war. The Boer War, fought out in the dry grasslands of South Africa, was the conflict on which they based past experience. Wounds sustained in the rich agricultural and heavily fertilised soil of France and Flanders behaved in a very different way. Overwhelming infection of rapid onset was to become characteristic of a conflict where wound contamination by soil rich in manure was the norm. As will be seen, the medical services had to make quick adjustments in their management of many conditions. They acquired experience in treating large numbers of casualties with many different types of wound. They were confronted by clinical situations they had not previously encountered, and they had to learn quickly from their experiences and particularly from their mistakes. They had to develop new techniques, because necessity is the mother of invention. Surgical specialties developed to keep pace with the problems surgeons encountered. Orthopaedic surgery had to resolve many acute problems on the Western Front, as well as having to deal with late problems back in the United Kingdom. The Great War led to a major expansion of orthopaedic centres in the United Kingdom. Significant numbers of facial wounds at the Battle of the Somme resulted in pioneering plastic and reconstructive surgical work on a massive scale to deal with the very difficult problems associated with these wounds.

Abdominal wounds were mostly treated by supervised neglect, or “expectant treatment”, i.e. no operations were undertaken at the start of the war. It would take the observations of astute clinicians, working in a logical and methodical way, and using scientific evidence from post-mortem studies of large numbers of cases, to bring about a change in management of abdominal wounds. Thanks to this pioneering work, early operative intervention became the accepted treatment for abdominal wounds, and survival figures improved. In a similar way, the management of chest wounds became more aggressive as confidence and experience grew. Major exposures of combined wounds of the chest and abdomen through an extensive thoraco-abdominal incision were performed and became standard practice. This approach will be explained in Chapter 8. Penetrating wounds of the skull and brain had been previously regarded as not worth operating on. Application of basic surgical principles to vast numbers of head-injured soldiers saw an active policy develop, with a concomitant improvement in survival. Fighting in trenches resulted in large numbers of facial wounds, and as will be seen in Chapter 10, this brought about major developments in treating these wounds, and the birth of modern plastic surgery.

Developments in microbiology led to improvements in the understanding of infections, and a study of pathological findings at post-mortems led directly to better ways of treating many wounds, thus keeping the patients alive! Blood transfusion with stored blood helped some of the wounded to survive. A better understanding of shock resulted in improved resuscitation of the wounded prior to surgery and developments in anaesthesia led to a better chance of surviving a surgical procedure. Diagnostic use of X-rays became established in base hospitals and casualty clearing stations, helping in the planning of procedures and removal of foreign bodies, such as bullets or fragments of shrapnel. All these aspects of medical and surgical developments will be dealt with in the following chapters of this book.

1. Neillands, R., The Great War Generals on the Western Front. London: Robinson Publishing Ltd, 1999, p.136.

2. Ibid., p.140.

3. Ibid., p.163.

4. Ibid., p.405.

5. Prior, R. & T. Wilson, Passchendaele: The Untold Story. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002, p. 195.

6. Neillands, R., The Death of Glory: The Western Front 1915. London: John Murray Publishers, 2006, p. 190.

7. Ewing, J., The History of the 9th (Scottish) Division 1914-1919. London: John Murray, 1921, p.398.

8. Stewart, J. & J. Buchan, The 15th (Scottish) Division 1914-1919. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1926, pp.286-7.

9. Prior & Wilson, op.cit., p.300.

10. Neillands, The Great War Generals on the Western Front, p.362.

11. Mitchell, T.J. & G.M. Smith, History of the Great War based on Official Documents. Medical Services. Casualties and Medical Statistics. London: HMSO, 1931, p.168.

12. Ibid., p.7.

13. “Some figures in medical history: James McGrigor”, British Medical Journal 1914, 2: pp.185-188.

14. “Naval and Military Medical Services”, British Medical Journal 1890; 1: p.1044.

15. Scarlett, E.P., “Officer and gentleman”, Canadian Medical Association Journal 1967: p. 1415.

16. Boyd, J., “Florence Nightingale’s remarkable life and work”. Lancet 2008; 372: pp.1375-1376.

17. Gordon, S., The Book of Hoaxes – An A-Z of Famous Fakes, Frauds and Cons. London: Headline, 1995, pp.35-36.

18. Smith, K.M., “Dr. James Barry: military man – or woman?” Canadian Medical Association Journal 1982; 126: pp.854-857.

19. Blair, J.G.S., “Sir Alfred Keogh – the early years”. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 2008; 154: pp.268-269.

20. Murray, J., “Sir Alfred Keogh: Doctor and General.” Irish Medical Journal 1987; 80: pp.427-432.

21. Blair, op.cit., pp.273-74.

22. Obituary: Sir Alfred Keogh. British Medical Journal 1936: 2: pp.317-318.

23. MacPherson, W.G. (ed.), History of the Great War based on Official Documents. Medical Services. General History. London: HMSO, 1921-24, Volume 1, p.22.

24. Atenstaedt, R.L., “The organisation of the RAMC during the Great War”, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 2006; 152: pp.81-85.

25. “Memorandum – the National Organisation of the Medical Profession in Relation to the Needs of HM Forces and of the Civil Population and to the Military Service Acts.” British Medical Journal 1916; 1; p.142.

26. Mitchell & Smith, op.cit., p.8.

27. Ibid, pp.ix-xii.

28. Ibid., p.13.

29. Ibid., p.108.

30. Ibid., p.16.

31. Ibid., p.108.

32. Ibid., p.178.