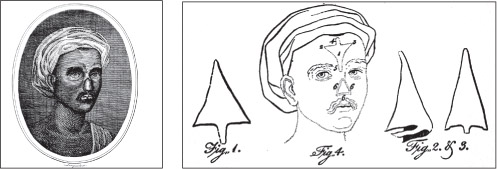

Figure 10.1 Two images showing the “Indian Rhinoplasty”. (Private collection)

War is the best school for surgeons.

Hippocrates

Everything has been thought of before, but the problem is to think of it again.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832)

Since ancient times man has devised surgical procedures to alter appearance, mostly for reconstruction after injury. Rhinoplasty (reshaping or reconstructing the nose) and treatment of burns were described in Egypt in 3000BC and nasal reconstruction (the “Indian rhinoplasty”) was described by Shushruta in 800 BC for restoration of the nose following its amputation as a punishment for crime.

The original technique used tissue taken from the cheek but this was modified later to use skin from the forehead. “Cosmetic” operations were recorded in Roman times to remove scars and to reshape nasal profiles. Celsus (Aulus Cornelius Celsus, ca 25BC to ca 50AD) even described circumcision reversal and correction of gynaecomastia (abnormal enlargement of male breast). Galen (Aelius Galenus, AD129-199/217), an accomplished philosopher and surgeon, also described various procedures but, during the Dark Ages, these writings were lost to the West, although some survived in the Arabic world. Superstitious beliefs during this time held back further surgical advances but, during the Renaissance, surgery was rediscovered, therefore allowing surgeons such as Tagliacozzi (1546-1599) to develop techniques to reconstruct the nose using a pedicled flap (see later) from the upper arm.1

This reconstruction however was not particularly robust and even Tagliacozzi himself regarded it as “virtual”, being in danger of falling off if blown too hard! The attitude of Tagliacozzi, however, was one of scientific and medical interest in the condition of the patient rather than the judgemental opinions of society at the time, which held that patients who had lost their nose as a result of syphilis or trauma were “punished by God”.

Figure 10.1 Two images showing the “Indian Rhinoplasty”. (Private collection)

Again, largely because of these types of beliefs, no further progress took place, until in 1794 a group of British surgeons observed an Indian rhinoplasty using a forehead flap. This was described in a letter to the Gentleman’s Magazine2 and provoked interest in Europe. The word “plastic” in surgery was perhaps first used around this time by the German surgeon Carl Ferdinand von Graefe (1787-1840) in his paper on this subject, “Rhinoplastik” in 1818.3

The term “plastic” (the Greek word πλαστικóζ is the past participle of the verb πλασσειν, to mould or to form) is frequently misunderstood. In modern usage it tends to mean something artificial, but in surgical terms it means the moving of tissue into a defect, permanently, to correct it. A definition of plastic surgery is “a remedying of a deficiency of structure (and function): reparative of tissue.”4

Defects in the surface of the skin can be repaired by various methods. The simplest is by direct (primary) closure – bringing the edges of the defect together and closing by sutures. If necessary, surrounding skin can be undermined and loosened to allow it to slide enough to close the defect. This method can be applicable for some large defects on the trunk and thigh. For other, perhaps even larger defects, for defects where there is insufficient local skin, or for smaller defects on the face which cannot be closed by this method, other ways of correction are needed. A simple and traditional technique employed was to allow the wound to heal by secondary intention (Chapters 2 and 6). It was left unclosed and nature’s own healing mechanisms caused the wound to shrink and allow the surface cells to grow over. This was, to a large extent, uncontrollable and wounds, especially those of the face, healed with a poor aesthetic and functional outcome (scars heal with shrinkage and distort the surrounding tissue).

In the early to mid 19th century, experiments were performed to “transplant” skin from one part of the body to another. These were largely successful, and by 1869, Reverdin5 was able to report useful application of tiny areas of epidermis (pinch grafts) onto a granulating bed of an ulcer, so allowing it to heal. Granulation tissue is a velvety tissue with a rich blood supply which grows over the surface of a wound or ulcer, and represents efforts of the body to heal itself. Its rich blood supply means it will readily allow a graft to “take”. This technique was developed further by Thiersch in Germany and Ollier in France6, who took larger areas of thin graft using a modified shaving blade and applied these to wounds. These grafts form the basis of modern split skin grafting. Free grafts depend for their survival on having a blood supply in the bed onto which they are put. In contact with an appropriate bed, after a few days, the vessels connect up with the residual vessels of the free graft, so allowing “take”.

There can, however, be considerable scar tissue around the bed, and this can lead to shrinking of the healed wound and graft causing contracture, giving unsatisfactory results, especially around the face. To a certain extent, this can be avoided by using a “full thickness” graft, one that contains the whole of the depth of the skin. By taking this extra tissue, scarring and contracture is less. “Split skin” grafts are thinner and only take the top layers of the skin. The donor sites heal by the epithelial (skin) cells remaining in the hair follicles and sweat glands in the donor site spreading over its surface. Full thickness grafts include these skin elements and the donor site cannot heal spontaneously in this manner. The donor defect needs to be closed directly or grafted with a further split skin graft to achieve healing. This, and the fact that getting it to “take” is more difficult, limits the useful size of full thickness grafts. Free grafts, also, are not suitable to cover defects without a viable blood supply in the base.

Exposed bone, cartilage or tendon, an open joint after a major wound or exposed foreign material, for example metal-work to hold a fracture in place, will not accept a free graft because there are no blood vessels to grow into the graft, which will consequently not regain a blood supply, and will turn black and fall off. In these cases it is necessary to move tissue with its own blood supply from elsewhere to close the defect. This tissue is known as a flap. The first flaps described (India and Italy) were not based on known anatomical blood supplies and can be said to be “random pattern”. The length/breadth ratio could not normally be extended beyond 1:1. The distal end (the free unattached end) of any flap made with dimensions beyond this ratio would be at high risk of dying. These flaps could be moved “locally” either by simple advancement directly into the defect or by transposition from an adjacent area of healthy non-injured tissue and are widely used in reconstruction to this day.

Tissue could also be brought in from a “distant” location. A skin flap was raised, leaving it attached at one end. The other end was then taken to a defect. After three weeks or so the moved component of the tissue would have acquired a blood supply from the bed into which it had been put, and the tissue joining it to its original site could be safely divided and returned to fill the donor defect or excised. This technique forms the basis of the “Indian” forehead flap for nasal reconstruction and can even be used, for example, to transfer tissue from one leg to the other as a “cross-leg” flap. A further development of this was the tube pedicle. Flaps were constructed in an area remote from the defect and two 1:1 ratio flaps raised in continuity end to end so making a rectangular flap with a 2:1 ratio. The edges of this flap were sewn together to form a tube and this was allowed to settle for three or so weeks.

Figure 10.4 Transposition flap. (Author’s collection)

The blood supply by this method was redirected within the flap into a longitudinal orientation. In other words, the blood vessels gradually realigned and adjusted to supply the flap in a longitudinal orientation from each end of the flap, which was not the orientation of vessels in the skin before the flap was raised. One end could then safely be detached and sewn into the defect in one or more stages. After two to three weeks, new vessels entered this part of the flap from the recipient bed. At this stage the donor end of the flap could be divided and the flap tissue moved to cover the defect. Several operations were often required to provide refinement to the end result. Importing uninjured tissue in this manner allowed an improved functional and aesthetic outcome than that provided by direct closure alone or by the use of skin grafts, especially around the face.

In 1889 Manchot7 had described the anatomy of blood vessels to the skin, and, if flaps had been based on these known blood vessels perfusing that area of skin, this 1:1 ratio could have been greatly extended. This would have given much greater flexibility to the use of these flaps as they could have been used further from the donor site. Although some mention of the vascularity (blood supply) at the base of some of these flaps was made by Gillies (superficial temporal artery at the base of the forehead flap allowing it to be made beyond the 1:1 ratio8 and Manchot’s diagrams being included in Davis’s textbook of 1919)9, the great leap forward into basing flaps on known blood vessels did not occur until much later (later 20th century) with the work of surgeons such as Ian McGregor in Glasgow10 and Ian Taylor11 12 in Melbourne, Australia and many others.

Technical advances in surgical microscopy and suture materials have allowed tissue based on single increasingly small vessels to be transferred as free flaps using micro-vascular anastomosis (joining up the two ends of tiny blood vessels), so avoiding the need to “waltz” pedicle flaps to their eventual site. For example, a muscle from the back called latissimus dorsi can be taken, and transplanted to the leg, most commonly to cover an exposed knee joint. The vessels which supply the muscle are carefully preserved, and then stitched (anastomosed) to equally small vessels in the leg, thereby providing healthy, richly vascularised tissue to cover the defect. These flaps were not used in treating casualties during the Great War. Patients with exposed knee joints, as a result of bullet or shrapnel wounds would have required an amputation (Chapter 6).

Religious and social taboos continued to influence developments in surgical techniques to correct or alter appearance. The wounds sustained in various conflicts, however, profoundly changed the attitudes of society at large and allowed a foundation for progress in methods of reconstruction. The Great War brought a new range of weapons to inflict damage on the soldier, sailor, and later airman, such as had not been seen in previous conflicts. These have been extensively discussed in previous chapters (chapters 2 and 7), so no further mention need be made of them here. Suffice it to say, that the type of trench warfare seen produced much greater numbers of wounds to the head and neck than had occurred in warfare before.

Early radical wound excision was a fundamental surgical principle established during the Great War, and has been discussed at length in chapters 2 and 6. For wounds of the head and neck, however, wound excision produced large defects that could not be closed by traditional techniques. It became necessary to devise methods of restoring casualties with these wounds back to as near normal an appearance as was possible.

At the beginning of the Great War, there was not an established plastic surgery specialty either in Britain or America. Any “plastic surgery” was performed by general surgeons as part of their overall repertoire of operations which they could perform. Although there was a good deal of medical literature, it was confusing and often contradictory, offering little help to the surgeon faced with what seemed to be an overwhelming number of casualties. Large defects of the face were closed primarily to achieve healing as soon as possible, with no real attention given to the functional or aesthetic result. Wounded servicemen (especially in Germany) were returned to the front as soon as possible, and this was sometimes with wounds that had not completely healed. The resulting disfigured appearance of these returning soldiers (mostly) had the effect of lowering morale not only in the patients, but also in his comrades with whom they had to live and fight.

The management and evacuation of wounded military personnel was streamlined during the Great War. Medical officers worked as appropriate in various locations in relation to the front (Chapter 2). In January 1915 an ENT Surgeon, Harold Delf Gillies, a New Zealander of Scottish descent, then aged 33, was sent to France.* At the 83rd (Dublin) General Hospital, Wimereux, just north of Boulogne, he met Charles Auguste Valadier, a flamboyant French “dental practitioner”.

Valadier was born in Paris on 26 November 1873 to a French pharmacist. As a child he went to live in America and became an American citizen. He went to Dental School in Philadelphia, qualifying in 1901, and gained his New York and Pennsylvania state examinations which enabled him to practice dentistry later. He practiced in New York and took on a French assistant (Robert Vielleville). Returning to France in 1910 he set up practice in Paris but, because he was without French qualifications, he had to use those of Vielleville in order to continue practicing. In the meantime Valadier enrolled with the Ecole Odonto-Technique de Paris to qualify as Chirurgien-dentiste from the Faculty of Medicine of Paris University in 1912. Thus he became a dentist fully qualified to practice in France.

Figure 10.5 Harold Delph Gillies in 1916. (Courtesy of British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons)

At the outbreak of the War he volunteered for service. For various reasons, perhaps because he was not by then a French National, he was taken on by the British Red Cross, rather than by the French. He reported for duty on 29 October 1914. He probably, thus, became the first dentist appointed for British troops. His, however, was only an honorary appointment, although he was given the rank of lieutenant.

By early 1915, Valadier had established a 50-bedded dental and jaw unit at the 83rd General Hospital at Wimereux, just north of Boulogne. He was by all accounts a wealthy man and much of the equipment that he used was provided by him. He gained a reputation for being rather flamboyant, especially as he had his own personal Rolls-Royce fitted up as a mobile dental surgery, from which he treated a large number of senior British and other Allied officers. He did, however, treat a large number of casualties using innovative techniques, and was experimenting with moving tissue around the face to repair defects as well as using bone grafts to replace damaged jaws.

His treatments remained controversial but he recognised that early closure of wounds wherever possible prevented undue scarring and contracture. He also advocated the retention of teeth around mandibular (lower jaw) fractures to allow the easier fitting of splints13, although this was disputed by others at the time14. Infection was prevented by draining the area through a sub-mandibular stab incision (incision below the lower jaw) and irrigation using a pump apparatus. Another technique was to close the remaining fragments of the mandible deliberately using temporary wires and cap splints after closure of the skin. The splints were connected by a jack screw which was turned to close the ends of the mandible. When callus (new bone, produced in response to a fracture, as part of the healing process) formation was seen on X-ray, the screw was reversed and the fragments distracted (pulled apart through the callus).

It was noted that new bone continued to form between the ends. When an adequate arch was established, a permanent plate was used to hold the position15, since the new bone was fragile and soft and would not have been able to withstand the stresses imposed upon it without the additional support of a metal plate. This, perhaps, was an early description of what today is known as distraction osteogenesis, a technique later described by a Russian, Ilizarov† 16, and now being developed widely in several areas of reconstructive surgery. Valadier’s standing locally necessitated the presence of a qualified medical practitioner for him to continue working. Harold Gillies was assigned to this task in early 1915.

This experience caused Gillies to develop an interest in facial reconstruction. He was lent a book written by a German surgeon (Lindemann) and was further inspired by some of the few illustrations in it. He wrote:

It was rather an informal war. The enemy did not seem to mind our learning of the good work they were doing in jaw fractures and wounds about the mouth.17

In June 1915 he went to see Hippolyte Morestin, an eminent and innovative plastic surgeon working in Paris. Morestin had a profound influence on Gillies.18 Morestin would have been better known had he survived into the peace at the end of the Great War. Unfortunately, he died at the age of 49 in the influenza pandemic of 1919 without having had the opportunity to report his wartime activity and experiences. What Gillies saw in Paris made him realise that there was a need for specialist treatment of casualties with wounds of the face. Through various political connections, Gillies enlisted the help of senior Army medical authorities Sir Anthony Bowlby, Consulting Surgeon to the BEF, and Sir George Makins, President of the Royal College of Surgeons 1917, to establish a dedicated unit for the treatment of servicemen with these injuries.

In late 1915, Sir Alfred Keogh, was Director General at the War Office, having gained military medical experience in the Boer War (1899– 1902). He had radically reorganised medical services to improve sanitation and effectively prevent communicable disease. He also tried to break down the barriers that existed between civilian and military medical practice, integrating the training of military personnel into civilian medical schools, as has been discussed in Chapter 1. As far as plastic surgery was concerned19, Keogh had already promoted the idea of establishing units to treat patients with specific individual wounds, for example, head injuries and orthopaedics. With large numbers of casualties, their needs would be best served by having all the experts in one place. Thus, the seeds for a specialist unit had already been sown, and it did not take much persuasion to set up a dedicated unit for the treatment of facial injury.

In January 1916 Gillies was ordered to report to the Cambridge Military Hospital, Aldershot “for special duty in connection with plastic surgery”. Thus the first Plastic Surgery unit in the UK was founded. There was a delay in equipping the new hospital so Gillies took the opportunity to visit France again to continue his observations on facial wounds. During this visit he observed a number of men who would have need of the new service but who were not being recognised as such. He himself purchased luggage labels onto which he put his own name and “c/o Cambridge Military Hospital”. These were sent out to advanced medical units and within a few weeks casualties were arriving in Aldershot with the labels attached. 200 patients were expected, 2,000 arrived! The opening of the unit had coincided with the beginning of the Somme Offensive in July 1916.

It soon became obvious that there was a need for rehabilitation facilities for treated servicemen and a house was acquired in Aldershot. This quickly became inadequate, and, after intervention by the Red Cross and the Order of Saint John, Frognal House, Sidcup was made available as the Queen’s Hospital. It was realised that a multidisciplinary team20 (perhaps not a term that would have been used then) would be required to treat these difficult and challenging cases. Gillies himself was closely involved in the design of the new hospital. A central admissions block had wards (each with 26 beds) radiating from it.

Figure 10.6 Architect’s drawing of Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

Accommodation for operating theatres, and dental, X-ray, radiography, photography and psychotherapy departments was arranged around the circumference of the site. There were also studios for the artist Henry Tonks, who painstakingly documented each case by drawing, and the sculptor J.W. Edwards, who made the plaster casts used for planning reconstruction. The hospital opened in August 1917 and initially had 320 beds, expanding to 600 by the end of the war. Queen Mary’s Hospital Sidcup, as it became, still exists, although not with a Plastic Surgery Unit. By July 1918, at least five satellite hospitals had been established in the Home Counties bringing the total number of beds available to Gillies and his team up to 1,000. With the increased number of beds came an expansion of medical, dental and nursing staff who came from all parts of what was then the British Empire – namely Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, as well as the United States of America, all of which supplied troops to the war. Men from each country therefore, had care from their own homelands, which added greatly to the efficiency of working and morale as well as adding a certain amount of competition between the teams. Gillies later wrote:

Our wounded had call upon surgical skill from the whole Anglo-Saxon race.21

Many of the records of the activity at this time were lost as result of bombing in the Second World War and the exact number of patients admitted is not known. The official statistics record that approximately 16% of the wounded admitted to casualty clearing stations had injuries of the face, head and neck22 and it is thought that around 5,000 were admitted to Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup. It is known, however, that up to the Armistice in November 1918, 11,752, operations took place at Queen’s Hospital (a rate of nearly 100 operations a week) and that after the Great War the work continued, with nearly 3,000 further operations being performed between March 1920 and April 1925 (until the Queen’s Hospital was closed in 1929, 18,135 military personnel were treated there; 8,000 of these had facial injuries).

Table 10.1

Numbers of wounds of the face, head and neck amongst 48,290 admissions to casualty clearing stations

Data from Mitchell, T.J. & G.M. Smith, History of the Great War based on Official Documents. Medical Services. Casualties and Medical Statistics. London: HMSO, 1931, pp.40-42.

Although Gillies was conversant with French developments in facial reconstruction, by his own admission23, he was unaware of historical descriptions of techniques and previous developments in plastic surgery describing plastic surgery as a “strange new art”24. As far as he was concerned he had to devise new operations to deal with the problems with which he was confronted. The vast numbers of casualties requiring treatment forced him and his team to improvise on a massive scale. Unfortunately, presumably because of the pressure of work, none of this “new” surgery was recorded at the time, and, whilst other specialties regularly published the results of their work in the British Medical Journal and other journals, there seems to have been almost nothing written about plastic surgery. A collection of case reports was put together and published as a now classic text book Plastic Surgery of The Face based on selected cases of War Injuries of the Face including Burns after the end of the war.25 In this he expounded his techniques, many of which were innovative, but perhaps more important were the innovations he brought to the total management of the patients. He by then had the chance to look at other work and wrote:

There is hardly an operation – hardly a single flap – in use to-day that has not been suggested a hundred years ago.26

All was brought together and analysed more in his two-volume work (The Principles and Art of Plastic Surgery) co-authored with one of his pupils, D. Ralph Millard, in 1957.27

Gillies noted that many casualties arrived at the hospital in a very poor condition with wounds far worse than anything he had seen before. Men arrived from the front through different clearing stations and base hospitals. They were wrapped in bandages, sometimes blind, poorly nourished and often unable to eat or speak because of the loss of function of the mouth, lips and tongue. Many were depressed and in a poor psychological state, and having seen their facial injuries did not wish to be seen by, or to communicate with others.

Infection was common and potentially fatal secondary haemorrhage from wound breakdown was a constant problem. Some casualties survived the difficult journey only to perish when in reach of definitive treatment. Evacuation from the Front was often in crowded transport requiring casualties to be moved sitting up. Once away from the frontline, where there was more space, well meaning but misguided attempts to alleviate apparent suffering and provide comfort by lying them down resulted in death due to asphyxia. Voluntary control of the tongue was lost as a result of the damage to the face and mouth and fell backwards into the pharynx so obstructing the airway with fatal consequences. This sequence of events was easily avoidable and perhaps these lessons had been learned by the end of the War.

Thus, many hurdles needed to be overcome before any corrective surgery was undertaken. Poor nutrition had to be corrected, infected wounds cleaned, fractured mandibles stabilised and basic dental work performed. In the early days at Aldershot, management was hastily thought out without recourse to description of previous techniques other than those seen by Gillies on his trips to France. Simple wounds were closed directly using existing anatomical landmarks, but gunshot and missile wounds usually involved complex loss of both soft tissue and skeletal elements (bone). Many wounds at that stage were closed by pulling tissue together with local advancement flaps, when new tissue should have been introduced. As time went on, however, more was learned and more complex methods of replacing lost tissue were used.

The most fundamental, and now perhaps the most obvious (but often forgotten) principle for planning treatment was one of diagnosis. Observation and accurate assessment was mandatory. A full history was taken, and a thorough physical examination was performed. Then, with the assistance of X-rays, photographs and sketches, the extent of each individual patient’s defect could be assessed and a treatment plan decided upon. Many members of the team were involved in this full assessment. The surgeon himself, nursing staff (who could observe difficulties in day-to-day living), dentists and technicians, radiologists, artist and photographer, all made a contribution to the overall case discussion. Early on, Gillies realised that it was difficult to relay in words an exact description of complex facial wounds. He, therefore, enlisted the help of Henry Tonks, a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons who had given up surgery to become an artist and had latterly been the Professor of the Slade Art School. With his help, sketches of the injuries were made and patterns made for any reconstructive procedures. Gillies himself also enrolled for an art course. Tonks had once told Gillies that:

Never is there a really fine architectural structure that is not functionally correct.28

Thus it came to be realised that, by correcting the lost functions of speech and eating, the appearance of the face would also improve.

Part of the diagnostic process was to understand the original defect. Patients could take up to a year from time of injury to be admitted to the unit, and by then the facial wound could have healed but with considerable scarring and resultant distortion of the surrounding tissue. There was often tissue loss, and before reconstruction could begin, the extent of this loss had to be ascertained. The healed wound would be taken apart and tissue returned to its normal position. At this stage, patients often looked worse than they had on admission (mirrors were banned on the wards so that patients avoided seeing themselves). If skeletal elements were missing, temporary prosthetics were made and the soft tissues mobilised over these to keep them in the correct position relative to surrounding structures.

George Napier Florence was born in Peterhead, in the north-east of Scotland on 12 May 1898, the fourth son of Robert and Bridget Florence. His father was a cooper/fish curer and it is thought that George had followed him into the trade. He was 16 (enlistment age was 18) when he followed three of his older brothers into the 1/5th (Buchan and Formartin) Gordon Highlanders in January 1915.29 In May 1917, the 5th Gordons, as part of the 51st Highland Division, were involved in the action around Arras in taking (and retaking) the chemical works at Roeux. The fighting was fierce and both German and British forces suffered heavy casualties (the 5th Gordon’s lost 11 officers and 234 other ranks).30 George Florence was listed as wounded in the Regimental Diary on 16 and 17 May 1917.31

Figure 10.7 G.N. Florence on admission to Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup, on 12 November 1917. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

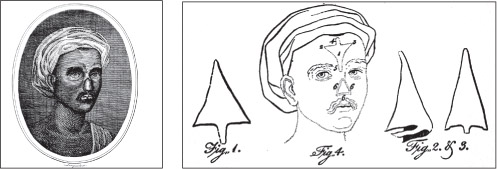

Figure 10.8 Operative diagram of first operation, septal and turbinate swing. (Adapted from original, courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

Figure 10.9 G.N. Florence 14 January 1918, after the first operation. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

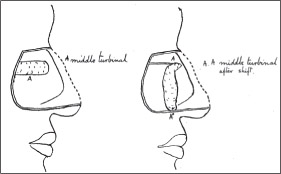

Figure 10.10 Operative diagram 2 February 1918 – forehead flap brought into orbit. (Adapted from original, courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

The details of George’s repatriation are not known, but, as he had sustained buttock wounds as well as the facial injuries, he may have spent some time at the Royal Herbert Hospital in Woolwich, which was a centre for orthopaedic injuries. The story goes that when he was in hospital the King visited and spoke of him to the doctors, saying, “you must help this young man”. It is believed it was as a result of this intervention by King George V that he was moved to the Queen’s Hospital.32

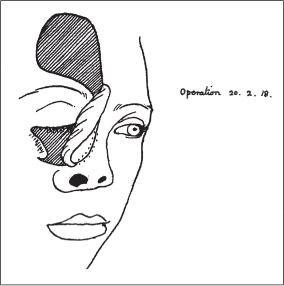

Figure 10.11 Operative diagram 21 May 1918 – forehead flap pedicle detached. (Adapted from original, courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

Figure 10.12 G.N. Florence 23 May 1918, two days after the second operation. The forehead flap donor site is unhealed. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives).

Figure 10.13 G.N. Florence 8 June 1918, eighteen days after the second operation. The forehead flap donor site is dressed, presumably after grafting. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives).

Figure 10.14 G.N. Florence 1 August 1918 – almost at the stage of discharge from Queen’s Hospital. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives).

The following is taken from the admission and operation notes written when George was a patient in Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup (courtesy of the Gillies’ Archives).

He was admitted 6 November 1917 (six months after injury) with a gunshot wound to the nose and right eye. A full assessment would have been undertaken, not only of the wound, but also of his general and nutritional condition as well as his psychological state. Photographs were also taken to record the pre-treatment state.

George’s wounds had healed but left him with an open nose and eye socket. On 19 November 1917 he underwent what was to be the first of seven or more operations. Lieutenant G. Seccombe Hett (an ENT surgeon, later to become Physician to Queen Mary and highly thought of by Gillies for his techniques of nasal reconstruction) moved the nasal septum (the central strut of the nose) and right middle turbinate (part of the lining of the nose) as flaps and closed the lateral side of the nose.

There was a period for this to heal and it is next noted, on 8 February 1918, that this septal swing and turbinate shift had been successful.

A flap was now prepared by introducing a skin graft under the skin of the forehead to form a lining for the inside of the nose. Twelve days later Seccombe Hett (now promoted to Captain) brought the flap down. The graft had taken well on the underside of this flap but had not taken on the donor forehead wound, the edges of which were closed as much as possible with tension sutures. A flap was mobilised moving the lower eyelid up to produce the slit of the eyelids. Cheek flaps were also moved to help fill the cavity on the side of the nose

Figure 10.15 G.N. Florence 6 June 1924, in the middle of revision operations after the war. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

By 21 May 1918 the forehead flap had lost its attachment because of infection but it remained attached to the nose. An operation then was undertaken to correct this by detaching the pedicle of the forehead flap and turning it into the nasal cavity.

It was noted on 10 June that the wounds had healed and the contour was good. On 2 October 1918 it was noted that George was discharged permanently unfit and it was not possible to fit an eye into the socket. The suggestion was made that an eye patch should be worn.

After the War various further operations were performed by Gillies himself to improve the function and thus his appearance.

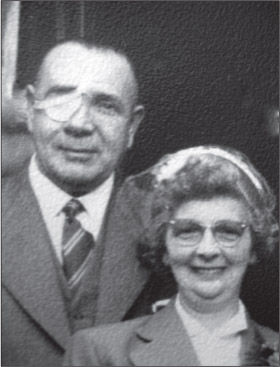

George continued to wear a flesh-coloured eye patch for the rest of his life. He also carried a piece of shrapnel in his buttock. In March 1918 he married a nurse/nursing assistant/volunteer, Queenie Coleman, who was possibly working at the Royal Herbert Hospital. His wife was the only person allowed to see George without his eye patch. He lived in Aberdeen and died in 1964 from a coronorary thrombosis (heart attack) after years of angina.

George’s son, James, emigrated to the USA and was looking for a house. In conversation with the vendor it turned out that he, the vendor, was a direct descendant of Harold Gillies. James bought the house and eventually died there. George’s wife, Queenie, also died there when visiting her son in 1986.

In the early days of the Great War, local flaps were the mainstay of reconstruction. On the whole they were simple enough to be done under local anaesthetic, and this helped in the management of the sheer numbers of casualties that arrived initially at the Cambridge Hospital. General anaesthetics at this time were difficult and were largely unsuitable for use in work on large facial wounds. These local flaps, raised and moved in many forms from adjacent areas of the face and neck, were used to fill relatively discreet defects of the face (as above). These could be quite large if there was normal skin nearby that could be utilised. For larger defects or injury affecting more of the face, such as burns, then tissue from outside the area needed to be imported to avoid undue distortion of the local normal tissue. This could be in the form of a skin graft, but the limitations of this have already been mentioned. Other solutions were required.

Figure 10.17 Diagram of neck/chest flap. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

Figure 10.18 A.B. Vicarage – flaps in position with some loss around the nose. Note the tubing. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

Figure 10.19 A.B. Vicarage – flaps now swung to reconstruct the nose. (Courtesy of the Gillies Archives)

Figure 10.21 A.B. Vicarage many years later. (Private collection)

A breakthrough came with the treatment of a seaman, one of 33 wounded, who had received burns to the face and neck whilst serving on HMS Malaya at the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. Casualties with burns were at this time initially treated in general hospitals, so it was not until August 1917 that he was admitted to Gillies’ unit with extensive scarring to the face, lips, nose and eyelids.

To release the contractures around the lips and chin, a bi-pedicled flap (see figures 10.16 to 10.21) was designed on the anterior neck and shoulders. This was brought up to the lower face and a slit made for the mouth. It was noticed that the skin near the base at both ends of the flap naturally formed itself into tubes. The edges were therefore sutured together to form a sausage-like tube. Some of the flap moved onto the face did not survive but it was noted that the “tubes” remained viable, soft and uninfected. Enough of these flaps survived to be swung up onto the face to resurface the cheeks and nose. Grafts were used to reconstruct the eyelids.

This observation gave rise to the development of the tube pedicle flap. The tubing was thought to stimulate the blood supply to run in a longitudinal direction within the flap. After three or so weeks this was sufficient for one end to be detached and for the whole flap still to be vascularised. One end could be detached and transported elsewhere. From there it picked up a new blood supply which joined on to the already longitudinal vessels within the flap. Again after a few more weeks the remaining original attachment could be lifted and that end moved. Tissue could thus be transported (“waltzed”) from remote uninjured areas to fill defects virtually anywhere else.

This concept had in fact already been used in September 1916 in Russia by Vladimir Filatov, an ophthalmic surgeon working in Odessa. The technique, however, was only published in May 1917 in Russian.33 There has been much argument about the originator of the tube pedicle.34 Gillies would not have been aware of the Russian account appearing just a few months before he “discovered” it, and it has to be considered that the two invented the concept at much the same time and independently. After all, necessity is the mother of invention.

A previous problem of distant flaps had been the exposed raw under-surface becoming over-granulated and infected. By forming the flap into a tube there was a completely enclosed skin pedicle which healed, so avoiding these complications. Reliability of these flaps therefore improved and they became more dependable. They were then able to be developed and became more refined, and, by the end of the Great War it was said that:

The wards at Sidcup resembled the jungles of Burma, teeming with dangling pedicles.35

Further advancements included raising flaps with attached bone for reconstruction of the mandible. Reconstruction using these techniques took time, and as can be seen from the narrative of George Florence, sometimes several years. The Queen’s Hospital was ideal for convalescence between operations. Patients had access to the large grounds of the Frognal Estate and many pursuits were set up to keep them occupied. Other local properties were also used for rehabilitation. In spite of this not all patients felt able to undergo the multiple operations required to complete reconstruction and they were discharged with other means to deal with their facial wounds (such as prosthetic masks).

The Indian forehead flap much used in the early days of the unit for nasal reconstruction was usually brought down as a skin flap without any inner lining at all. It may have been draped over a bone or cartilage graft for support and was made 30% larger than the defect to allow for subsequent shrinkage. It was noticed that one patient in whom the turbinates (part of the lining of the nose) had been turned upwards for support maintained the reconstruction without this post-operative shrinkage. It was realised that this was because the turbinates had provided a mucosal lining for the nose and prevented its collapse. The understanding of this concept of reconstructing all layers, “cover, support and lining”, is a principle underlying the practice of plastic surgery to this day.

After restoring the facial skin in these patients there remained the problem of the defects in the underlying facial skeleton, mandible (lower jaw), maxilla (upper jaw), nose and orbits (eye sockets). The unit evolved to treat these injuries as a result of co-operation between dentists (Gillies’ initial interest, it must be remembered, had been stimulated by his contact with the dentist Valadier) and, mostly, ENT surgeons. Restoration of facial appearance could only be effective if the reconstructed skin had an intact skeletal framework on which it could sit.

Figure 10.22 A sketch by Tonks of Gillies operating. (Courtesy of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons)

This co-operation was confirmed with the appointment of Captain (later Sir) William Kelsey Fry, a medical officer in the 1st Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers, to the Cambridge Hospital. He had been wounded twice and awarded the Military Cross, and was on “home service”. The suggestion was made by Fry to Gillies that, as a dentist, he would “take the hard bits and that Gillies should take the soft bits”. Prosthetic appliances were developed to hold the skeletal structures in place whilst soft tissue was restored over it, and bone grafts were then used to consolidate the facial skeleton. It would appear that bone grafts were also taken from other patients, although little detail is given about the techniques used, how rejection was dealt with and the long-term results.

None of these more complex operations could have been performed without the use of general anaesthetic. At the beginning of the war most anaesthetics used ether or chloroform given through a mask applied to the face. For obvious reasons this was not suitable for the type of surgery being undertaken on these patients, as the mask would have hindered the surgeon in gaining access to the area on which the operation was to take place. Various tube mechanisms were devised to administer the anaesthetic gasses to the patient and indeed these developments went on to form the basis of the endo-tracheal tube used in modern anaesthesia (see Chapter 3).

A consequence of anaesthesia during the Great War was the unpredictability of blood pressure control. The face has a very rich blood supply. With too high a blood pressure, excessive bleeding was a problem for the surgeon. Not only was there excessive blood loss, but also, blood obscured the surgical field, thus making any procedure technically more difficult and therefore prolonged. One solution to this problem was to operate with the patient sitting up, a strain on the backs of all concerned.

There is no doubt that the work performed at the Cambridge Hospital in Aldershot, and later at the Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup, and at the other hospitals dealing with wounds of the face produced results of far greater quality than anything that had been achieved before. In spite of the relative paucity of information and guidance available at the time, principles of treatment emerged from the sheer numbers of cases treated The analytical approach to diagnosis, on which sound practical management could be based, permitted techniques to be developed on a firm clinical base, very much to the advantage of those treated and for the future of facial reconstruction. It also allowed for the development of plastic surgery as a separate specialty in the field of medical practice.

This experience also allowed other aspects of care of these injured servicemen to be developed. Patients who had lost limbs were often celebrated as heroes. The injured part could be hidden from sight whether or not a prosthesis (artificial limb) was worn. This was not an option for those who had suffered facial loss and the results of the injury would remain open for all to view. Facial deformity represented a loss of identity and with it a loss of humanity.36 Patients would regard themselves as being socially unacceptable because of their appearance and many were reluctant to return home to their family and friends because of this. It was also difficult for outsiders to look at them without a sense of shame or even revulsion.37 In Germany, patients were even treated in institutions for the blind so that no-one would see them. Gillies himself noted that,

… only the blind kept their spirits up through thick and thin.38

Psychological disturbance was understandably common and comments in the newspapers at the time reported a high incidence of depression. Of course, not all reconstructive procedures went exactly to plan. It was noticed that if the results were not as good as expected, depression was more likely. On the other hand, if the reconstruction went well, patients tended to recover their pre-injury state more quickly.39 This was recognised and the Queen’s Hospital was designed with rooms for psychotherapy. What form this took is not recorded although it perhaps heralded the first formal co-operation of psychologists and surgeons in treating patients with disfigurement as a result of injury. It also demonstrated that a holistic approach to management was taken in which these casualties of war were treated as individuals rather than clinical cases.

The success of the Queen’s Hospital owed much to the presence of practitioners from many different specialties and disciplines, but it was the co-operation between dental surgeons and, initially, ear, nose and throat surgeons that formed the basis of the multi-disciplinary team. Added to this were surgeons from around the world, together with others in supporting roles, radiologists and radiographers, artists, sculptors and technicians. The role of nurses and their helpers in caring for all the needs of the patients, both physical and psychological, was acknowledged and much appreciated.

In 1911, Gillies had married Kathleen Jackson, a nurse who was much involved in the care of the patients. Nursing regimes were strict, with prescribed methods for tasks such as dressing changes.40 Overall, however, a rather informal style of management was encouraged from all staff, in contrast to the necessarily formal environment in the armed forces. This put patients at ease and helped their recovery. This multidisciplinary approach to the care of complex cases was new at the time and is an excellent illustrative model for how complex cases are managed today.

At the start of the war, there was a considerable amount of literature on procedures that might have been described as “plastic surgery”. It was, however, rather disorganised and there were no reports of tried and tested methods on which someone faced with patients who arrived in such numbers could turn for guidance. Indeed much of what had been written by then could be described as science fiction.41 Thus, much of the “plastic surgery” performed by Gillies and others at the time was by definition, innovative, in that it had not been read about or seen by any of the operators.42 The experience of treating over 5,000 injured servicemen by the time the War had ended led to an organisation of knowledge in the form of two major textbooks by J.S. Davis in 1919 in America43, and Gillies in Britain in 192044. Both authors commented on the lack of previous useful literature available to them and other surgeons. Although mostly collections of case reports, they were organised and accurate, so forming a base on which future developments could be made.

Figure 10.23 George and Queenie Florence at their son’s wedding in 1957. (Courtesy of Diane Florence, the granddaughter of George Florence)

In one respect, however, with the benefit of hindsight, an opportunity could be said to have been missed. The tube pedicle was a tremendous success in terms of bringing uninjured tissue to restore large facial defects and was a great improvement on other existing reconstructive methods. Much intellectual energy was expended in perfecting the techniques of raising, transferring and dressing this flap and the understanding of its limitations. Davis45, in his book, included diagrams of Manchot’s46 work describing specific blood vessels supplying the skin but made no mention of it in the text. Gillies described extending the length of a flap taken with the superficial temporal artery in its base for eyebrow reconstruction.47 This observation was not taken further, and the realisation that all skin was supplied by specific blood vessels and that flaps could be raised on these was not made at the time. Had the connection been made, the tube pedicle would not still have been in use until well after the Second World War.

Perhaps, however the most important legacy was the generation of young wounded servicemen who, as a result of the treatment they received under the care of Harold Gillies and his team, were able to return into society in a manner that would have been impossible before.

Queenie Florence regularly spoke with such pride that George had “been chosen by the King” and for getting such wonderful treatment by Sir Harold Gillies, who was always referred to by name. When she spoke, it always seemed to be on behalf of them both, so one can hopefully assume that George felt the same way.48

1 Tagliacozzi, G., De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem. Venice: Gaspar Bindonus, 1597.

2 The Gentleman’s Magazine, October 1794, p.891.

3 von Graefe, C.F., Rhinoplastik, oder die Kunst, den Verlust der Nase organisch zu ersetzen. Berlin: Realschulbuchhandlung, 1818.

4 Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

5 Reverdin, J.L., “Greffe épidermique”, Bulletin de la Société de chirurgie de Paris, Paris, 1869 10: pp.511-515.

6 Klasen, H.J., History of Free Skin Grafting: Knowledge or Empiricism? Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1981.

7 Manchot, C., Die Hautarterien des menschlichen Körpers. Leipzig Vogel, 1889.

8 Gillies, H.D., Plastic Surgery of the face based on selected cases of war injuries of the face including burns. London: Henry Frowde, Oxford University Press, Hodder & Stoughton, 1920.

9 Davis, J.S., Plastic Surgery – its Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: P. Blackston’s Sons, 1919.

10 McGregor, I.A. & G. Morgan, “Axial and random pattern flaps”, British Journal of Plastic Surgery 1973; 26: pp.202-213.

11 Taylor, G.I. & P. Townsend, “Composite free flap and tendon transfer: An anatomical study and a clinical technique”, British Journal of Plastic Surgery 1979; 32: pp.170-183.

12 Taylor, G.I. & J.H. Palmer, “The vascular territories (angiosomes) of the Body: experimental study and clinical applications”, British Journal of Plastic Surgery 1987; 40: pp.113-141.

13 Valadier, C.A. & H.L. Whale, “A note on oral surgery”, British Medical Journal 1917; 2: pp.5-6.

14 Colyer, J.F., “A note on the treatment of gunshot injuries of the mandible”, British Medical Journal 1917; 2: pp.1-3.

15 McAuley, J.E., “Charles Valadier: a forgotten pioneer in the treatment of jaw injuries”, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 1974; 8: pp.785-789.

16 Ilizarov, G.A., “The tension-stress effect on the genesis and growth of tissues. Part 1 – The influence of stability of fixation and soft-tissue preservation”, Clinical Orthopaedics 1989; 238: pp.249-285.

17 Gillies, H.D. & D.R. Millard, The Principles and Art of Plastic Surgery. Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1957.

18 Lalardrie, J.P., “Hippolyte Morestin 1869-1918”, British Journal of Plastic Surgery 1972; 25: pp.39-41.

19 Martin, N.A., “Sir Alfred Keogh and Sir Harold Gillies: their contribution to reconstructive surgery”, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 2006; 152: pp.136-138.

20 Brown, R.F., C.W. Chapman & B.C. McDermott, “The continuing story of plastic surgery in Britain’s Armed Services”, British Journal of Plastic Surgery 1989; 42: pp.700-709.

21 Gillies, H.D., Plastic Surgery of the face based on selected cases of war injuries of the face including burns. London: Henry Frowde, Oxford University Press, Hodder & Stoughton, 1920.

22 Mitchell, T.J. & G.M. Smith, History of the Great War based on Official Documents. Medical Services. Casualties and Medical Statistics. London: HMSO, 1931, pp.40-42.

23 Gillies & Millard, op.cit.

24 Pound, R., Gillies: Surgeon Extraordinary. London: Michael Joseph, 1964.

25 Gillies, op.cit.

26 Ibid.

27 Gillies & Millard, op.cit.

28 Gillies & Millard, op.cit.

29 Morrisey, C., “1st/5th Battalion Gordon Highlanders: A Brief Summary of the Battalion’s History 1914– 1918”, http://gordonhighlanders.carolynmorrisey.com/History.htm accessed 1 April 2011.

30 Falls, C., The Life of a Regiment: The History of the Gordon Highlanders. Volume 4:1914-1919. Aberdeen: The University Press, 1958.

31 Battalion War Diary, 1st/5th Gordon Highlanders, May, 1917.

32 Florence, D., (granddaughter) – personal communication 2011.

33 Filatov, V.P., “Plastic procedure using a round pedicle” [in Russian], Vestnik Oftalmologii 1917; 34: p.149. English translation appeared in Surgical Clinics of North America, 1959; 39: p.261.

34 Webster, J.P., “The early history of the tubed pedicle flap”, Surgical Clinics of North America, 1959; 39: pp.261-75.

35 Gillies & Millard, op.cit.

36 Gilman, S.L., 1999, cited in S. Biernoff, “The Rhetoric of Disfigurement in First World War Britain”, Social History of Medicine (in press).

37 Van Bergen, L., Before my Helpless Sight – Suffering, Dying and Military Medicine on the Western Front 1914-1918. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009.

38 Pound, op.cit.

39 Gillies & Millard, op.cit.

40 Gillies, H.D., “Nursing in plastic surgery and maxillo-facial injuries” in J.M. Mackintosh (ed.), War-Time Nurse: An Anthology of Ideas about the Care and Nursing of War Casualties. London: Oliver & Boyd, 1940.

41 Freshwater, M.F., “A critical comparison of Davis’ principles of plastic surgery with Gillies’ plastic surgery of the face”, Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery 2011; 64: pp.17-26.

42 Obituary, British Medical Journal 1960; 2: pp.866-867.

43 Davis, op.cit.

44 Gillies, H.D., Plastic Surgery of the face based on selected cases of war injuries of the face including burns. London: Henry Frowde, Oxford University Press, Hodder & Stoughton, 1920.

45 Davis, op.cit.

46 Manchot, op.cit.

47 Gillies, op.cit.

48 Florence, D., (granddaughter) – personal communication 2011.

* Harold Delf Gillies was born in Dunedin, New Zealand on 7th June 1882. He was sent to school in England at the age of eight and went to study Medicine at Caius College, Cambridge and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, qualifying in 1908.

He was appointed OBE in 1919, CBE in 1920 and Knighted in 1930. He continued to work as a Plastic Surgeon and in the Second World War was again involved in treating injured servicemen. In 1946 he became the first president of the newly formed British Association of Plastic Surgeons. He died in 1960.

† Gavril Ilizarov (1921–92) was a Soviet surgeon who, in 1944, was sent to the city of Kurgan in Western Siberia to treat soldiers with broken legs. He developed an apparatus to hold fractured bones in place from horseshoes and bicycle spokes and noticed the device could also be used to lengthen the bones if there had been loss.