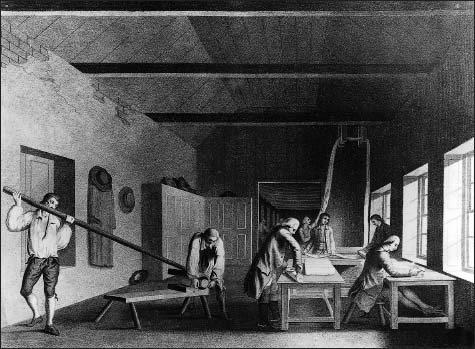

PLATE 11

Perspective View of a Lapping room, with the Measuring, Crisping or Folding the Cloth in Lengths, picking the laps or lengths, tying in the Clips, acting by the mechanic power of the Laver to press the Cloth round and firm, and Sealing it preparatory to its going to the Linen hall …

WILLIAM HINCKS 1783

THE CURRENT DEBATE on the merits of the concept of protoindustrialisation should make us re-examine the case of the Ulster linen industry. Leslie Clarkson referred to it often in Proto-Industrialization: The First Phase of Industrialization? (1985).2 Reviewing his book, Pat Hudson urged us:

to analyse the inter-related nature of factors in the environment of industrial regions. How manufacturing locked in with the agrarian base through the seasons and between regions; how the institutional environment of landholding, inheritance practices, the distribution of wealth, the nature of central and local government, and the role of urban centres were all crucially linked in providing the ether of expanding commerce and industry. Above all, the proto-industry debate has properly integrated the study of the family and households, gender and generational relationships, personal life, motivations and aspirations, demography, and work regimes …3

There can be no doubt that such an approach to the study of the Ulster linen industry would illuminate many aspects of economic, social, cultural and political life, and make the history of the province more intelligible. The obstacle is that The Rise of the Irish Linen Industry (1925) by Conrad Gill is a classic of economic history.4 Although its structure makes it difficult to comprehend, the authority of Gill’s account has not been questioned. Yet Gill made a serious error in arguing that the ‘cottage industry’ of the first half of the eighteenth century evolved thereafter into a ‘putting-out’ system. He had fallen into the trap of believing ‘in some progressive and linear evolution towards modern factory production’5 and was searching for the factors that converted a system based on artisan production into one relying on a ‘putting-out’ structure.

This study attempts to provide a more accurate picture of the trade on the eve of its industrialisation, re-interpreting the evidence that was available in Gill’s time. It will argue that a system of ‘public markets’ served by artisan weavers dominated the pre-industrial linen trade in Ulster, whereas the cotton manufacture there was organised on a putting-out system. Relevant to this is an examination of regional differences in the kinds of linen produced and of how different regions reacted to the loss of many weavers to the cotton manufacture that was burgeoning in the Belfast region. Finally, the study will suggest how linen in Ulster was able to industrialise successfully (to the surprise of its competitors in England and Scotland), and why this development was confined to much narrower territorial limits than those of the domestic era.

The linen trade in Ulster had begun to develop on commercial lines in the late seventeenth century; a London-published pamphlet of 1682 notes ‘Ulsters’ in the Book of Rates, as well as imports of Irish yarn.6 Stimulated by demand in the English market, Dublin factors purchased bleached webs of linen brought to the capital by northern linen drapers: for their benefit a Linen Hall was erected in 1728. Throughout the first half of the eighteenth century, trade in linen in the north was gradually concentrated in the hands of these drapers. In markets and fairs throughout the province they purchased unbleached webs from the weavers and organised the bleaching, sometimes in bleachgreens of their own but also by negotiating contracts with bleachers. For their part these bleachers began to reduce costs by introducing new bleaching methods and technology, and to increase the annual output of their greens.7 The consequent cheapness of well-bleached good quality linens assured the Irish industry of success in the English market, so that exports surged from less than 2.5 million yards in the second decade of the century to almost 8 million in the 1740s and 17 million in the 1760s.

In the first half of the eighteenth century there was a strong emphasis on the promotion of colonies of weavers in manufactories where the supervisor provided the raw materials and managed production. This was the model introduced into Lisburn by Louis Crommelin in 1698.8 None of these projects, except those involving the production of damasks on complex draw-looms, survived in Ulster into the second half of the century. Yet they appear to have left their mark on the structure of the industry, for in the Lagan valley and north Armagh many weavers in the 1760s and 1770s continued to employ journeymen weavers, paying them their board and lodging and one-third of what they earned. Some weavers also took yarn for weaving from ‘manufacturing drapers’ (as they were termed).9 Yet even in that district, as in the rest of the province, the emphasis was on independent farmer/weavers growing their own flax, having it processed into yarn by their womenfolk, and selling it in the public brown-linen markets to drapers who attended from neighbouring towns. When a weaver was not able to raise the price of the yarn he had either to work for hire for those who advanced him the yarn, or take credit with the yarn-jobber.10

It was the 1760s, a period of rapid expansion, that attracted the attention of Conrad Gill, interested as he was in the structure of the workforce employed in the industry. He decided that the rapid expansion of trade must have brought about important changes in organisation that were linked to a drift towards capitalism. He diagnosed in the circumstances of a famous riot in Lisburn in 1762 the symptoms of change: ‘the old system of domestic manufacture and sale in open markets was gradually yielding to new methods’.11 He decided that by the 1760s ‘a class of permanent employees had appeared’ and reckoned that in the year 1770, while rather more than 35,000 weavers in Ulster were still independent, as many as 7,000 or one-sixth of the weavers were employees working either for ‘small manufacturers’ (independent weavers) or for some ‘manufacturing drapers’ puttingout yarn. By 1784 he considered that probably ‘rather more than 40 per cent of 40,000 weavers’ (i.e. 16,000) would have been employees. According to Gill this trend continued:

It seems probable, then, that there were about 70,000 weavers in Ulster at that time [c.1820] and that rather more than a third of their output was produced on a large scale. The number of weavers of the three different classes (independent craftsmen, employees of small manufacturers, and employees of large firms) would not be exactly proportioned to their output; for the wage earners would give most of their time to weaving, whereas the independent craftsmen would have to devote some time to farm work and to attending markets. Therefore, a third of the weavers, and perhaps rather more, may still have been independent.12

If Gill had restricted himself to pointing out the existence on a large scale of employees working for wages no-one could have disagreed with him. The county statistical surveys of the early nineteenth century refer regularly to master weavers who in towns hired journeymen to work in their workshops, or in rural areas let out small cot-takes of land to cottier-weavers who paid their rent in weaving. These two categories obscure many degrees of dependence, notably sons working for their fathers, or weavers taking yarn from jobbers either in hard times or until their own flax crop was harvested, scutched and spun.

Gill, however, was concerned rather with locating his ‘manufacturing drapers’, capitalists in the trade employing labour. It was not difficult for him to find damask weavers working under capitalist conditions, because large workshops or factories were required to house the considerable number of men (from six to 16) needed to set up and work a draw-loom, and to maintain regular supervision of the patterns woven into the expensive cloth. The very high standard that they could attain is now evident from a superb tablecloth woven in 1728 in Waringstown, County Down, measuring 11 feet by 9 feet and depicting a coronation procession and a map of London.13 The number of damask manufactories, however, was very small in the eighteenth century, so their employees would have constituted a tiny percentage of the weaving population. Therefore Gill concentrated his strategy on the bleaching districts. He suggested that ‘in order to gain a more exact idea of the growth of capitalism we need to distinguish between the areas of rapid change, in which production on a large scale was common, and the conservative districts, where capitalism had made little headway’. He designated the linen triangle (the south of Antrim, the centre and west of Down, and the north of Armagh) and the east of Londonderry ‘as districts in which capitalism was the most fully developed’. He explained the process of evolution:

The fact that so many of the employers were bleachers had an interesting effect on the grouping of population. In earlier times, when practically the whole demand for brown linen came through the open market, weavers would naturally wish to live near to a town, for convenience in selling their cloth and buying flax or yarn. But with a steadily increasing demand on the part of bleachers for the direct supply of cloth by means of hired labour, weavers gradually settled in larger and larger numbers in the neighbourhood of bleachgreens. The census returns [of 1821] show time after time a bleachyard, the owner’s house, and a little community of bleachyard workers and weavers settled round them.14

To this final sentence Gill added an explanatory footnote: ‘To give one example out of many, close to the bleachgreen of William Hudson, near Banbridge, nineteen households of his employees – bleachyard hands and weavers – were settled’. Yet these weavers would have been able to supply no more than a tiny percentage of the webs that Hudson finished each year in his bleachgreen. Throughout the explanation, in fact, Gill is forced to scrabble about for evidence. Contemporaries record that the linen producing districts were already densely populated by the 1760s, geared to thousands of independent weavers selling their webs of cloth in the brown linen markets held in many provincial towns.15 To account, therefore, for concentration of settlement around bleachgreens Gill seized on McCall’s mention of the migration by 1800 of weavers from towns to the countryside.16 From which towns could they have come? Surely not from Belfast, to which weavers were migrating to earn higher wages from cotton-weaving; nor from Armagh, where weavers in 1770 composed less than two per cent of the occupations; nor from thriving towns like Lisburn, Lurgan, Newry, Banbridge or Dungannon. It is important to remember that Gill was trying to account for between a quarter and a third of all the weavers.

Gill was able to argue a more impressive case for capitalists in the industry putting-out yarn to be woven for wages:

Different yarns were often needed for warp and weft, so that a weaver might have to spend many hours in an expedition in search of warp yarn, many more in buying weft, in addition to his day at the market for the sale of his web. Production could be carried on more cheaply if a draper or manufacturer bought the yarn, supplied it made up into chains or wound on pirns, and received the cloth without waste of time when it was woven.

There can be no doubt then, that the supply of flax or yarn, in increasing quantities, in greater variety, and from a wider area, was one of the chief causes of change in the organisation of manufacture.17

Yet even here Gill overstated his case. He seems to have failed to appreciate the significance of widespread flax-growing and yarn-spinning in the rural economy not only of Ulster but of the neighbouring counties of Leinster and Connacht. A multitude of yarn-jobbers was able to tour the rural districts there to purchase the yarn and transport it to the brown linen markets in the Ulster towns, where it was sold throughout the weekly market day.18 These men were regular in attendance and it was not difficult for a weaver to obtain the warp and weft that he needed, knowing that the quality was guaranteed by regular inspection as well as by the jobber’s reputation. In these circumstances middlemen had few opportunities, especially as regrating (purchasing to retail at a profit) was expressly forbidden by law.

The last people who would have been prepared to venture their capital in yarn would have been the bleachers. They needed their money to purchase brown linens in the markets but they also had to continue to invest in improving their bleachgreens in order to remain competitive. From the early days the bleaching and finishing trades had attracted investment, especially after the application of water power to the wash mills and the beetling (i.e. finishing) mills.19 In the second half of the eighteenth century the average output of bleachgreens rapidly increased: whereas few greens in 1750 could bleach more than 1,000 pieces, there were many in the early nineteenth century that could finish in excess of 10,000 pieces. The major factor in this expansion was the introduction of chemicals that greatly reduced bleaching time and allowed bleaching round the year instead of in the summer only.20 These improvements cut bleaching costs and caused intense competition among the bleachers so that many of the smaller firms disappeared, especially after 1800.21 Those bleachers who remained dominated the trade.

Gill’s interpretation of the structure of the brown linen trade in the early 1820s bears a marked contrast to the evidence presented to a select committee of the House of Commons inquiring into the linen trade of Ireland in 1825.22 The whole tenor of this report is founded on the assumption, by all parties concerned, that almost all the linens woven in Ulster were sold through the brown linen markets. The select committee wanted the Irish representatives to explain why the markets were still so popular when there were obvious alternatives that would seem to have been more convenient for both buyers and sellers. Why, for instance, did the weavers not just take their finished webs to the nearest bleachgreens at their convenience instead of waiting until the next market day? Why did the buyers not just buy from local dealers who would then make it their business to keep a large stock of assorted linens? The reply from all three senior representatives of the Ulster linen industry giving evidence to the select committee was that both buyers and sellers much preferred to sell in the open markets. Because the conduct of markets had evolved over more than a century the trade had a certain rhythm. It was controlled by the bleachers who had introduced profitable techniques to bleaching in the 1730s and as a consequence had absorbed the class of drapers that had originally been the dealers and buyers in the markets. By the close of the eighteenth century the term ‘draper’ was applied indiscriminately to both the bleachers and the buyers whom they employed to tour the linen markets buying an assortment of linens that would enable them to fulfil their orders from Britain and abroad. As one of them explained:

Buyers that attend on Monday at Banbridge market, when they have made their purchases there, and paid for them all with ready money, the next market they go to is Armagh, which is fifteen or sixteen miles distant; there they have the same business to do on Tuesday; and it produces also great expedition to the seller: there he sells his linen at once, and finds the people at once that purchase his description of goods; as linens vary very much both in quality and fineness. Then, after Armagh, the next market he goes to is generally on Wednesday, Tanderagee. The next day, Thursday, there is a market at Newry which he attends; and the following day, Friday, there is a market at Lurgan, which he attends. There is also one at Cootehill, he may go to, or at Belfast, there are markets on Friday at each of those three places; and then on Saturday there is a market at Downpatrick; and also in Ballymena, in the country of Antrim. Linens are sold in various parts of the country in the market towns. There is a market every day in the week …23

The bleachers were satisfied that this system of markets enabled their own employees, most familiar with the marketing policies and requirements of their firms, to buy fifty or sixty webs in a three-hour period at a market, confident that their length, breadth and quality had been inspected earlier that same day by a public sealmaster licensed by the Linen Board. During the bleaching season they were able to purchase a wide variety of linens at a range of prices by touring markets and fairs, some of which were a considerable distance from their base. This was the case in 1759 when Thomas Greer of Dungannon recorded in his market-book visits not only to neigh-bouring towns but also to Monaghan and Cootehill. By 1825 men like John Andrews of Comber purchased linens from markets much further afield: as well as buying in Belfast, Lisburn, Downpatrick and Kircubbin, he had buyers attending the several markets in Armagh, Tyrone and Londonderry ‘in order to enable us to make out a fair assortment’. He explained that his firm had to supply ‘such an assortment as would enable us to hold our connections and go on with our business, for we can only hold our connections in this country [Britain] now, by supplying them with articles of all varieties’.24 For their part the weavers preferred to attend public markets where they were confident that the buyers were competing fairly for their linens, so that demand affected price.

It is quite clear from the report of the select committee that the pattern of markets had evolved to suit the structure of the industry. The committee itself was inclined to believe that the prevalence of this system of markets was due to the enforcement of a linen act of 1764 (3 Geo. III, c. 34) and even quoted a clause that linen yarn ‘shall be sold publicly in some open market or fair, between the hours of eight of the clock in the forenoon and four of the clock in the afternoon’, and brown or unbleached linen ‘between the hours of ten of the clock in the forenoon and four of the clock in the afternoon’. However, it was informed that the law was not strictly enforced in practice, except for the clause prohibiting dealing before the bell sounded to announce the commencement of the market. When it criticised as inadequate the fixed hours and dates of the markets, it was told that weavers who had not sold all their linens in the public market usually approached a buyer afterwards to negotiate a price; between markets weavers even took their cloth direct to a bleachyard for sale. The implication was that although the 1764 act did specify that all linens had to be sold in public markets, a blind eye was turned to arrangements made privately between bleachers and weavers because they were on such a small scale.

In short, the structure of the brown-linen trade that had been endorsed by the 1764 act operated so well that it continued to be accepted in principle by all parties, even if not enforced in detail, up until industrialisation. Just as significant, in the light of Gill’s conjectures, are the references by witnesses to the activities of his ‘manufacturing drapers’. Although one of the most important markets for fine linens was held in Belfast, it is well known that by 1825 there were no linen weavers in the town and district because cotton weaving was more profitable. That market, however, was supplied to a large extent from the neighbouring districts of County Down by ‘many extensive manufacturers in the country towns, small towns in the neighbourhood of Belfast, who bring in each week a quantity of linens to Belfast market, a distance of, from six or eight to fifteen or sixteen miles, and then they find customers’.25 It had been reported in 1816 that ‘Belfast market is made up by rich manufacturers, who bring ten to forty pieces to it’: yet 400 manufacturers attended that market to sell 1,000 pieces weekly, which would suggest that the rich manufacturers made up only about 10 to 15 per cent of the attendance.26 A witness before the 1825 select committee, himself a substantial draper, added that the weavers preferred to deal with him in the public market-place rather than come to his warehouse, because they wanted competition between the buyers. Away from the major market towns, the same witness pointed out, it had become the practice for small manufacturers to sell to more substantial manufacturers who could afford the time to travel to markets.27

As well as such manufacturers buying linen in local fairs and markets to sell at a profit in major markets, there were other men mentioned in the 1825 report who might be more accurately termed entrepreneurs or capitalists. The reason for their appearance was that suggested by Gill: all of them were able to corner part of the yarn supply and put it out to weavers. This enabled them to specialise in the production of certain types of cloth for which they knew there was a ready export market. Yet, although the select committee of 1825 was anxious to learn everything about enterprises that accorded so well with their suggestions for the future of the trade, very little evidence was proffered. Smith of Seapatrick was reported to be concentrating on six quarter (i.e. 54 inch) wide sheeting, ‘the best sheeting that I have ever seen made in Ireland’ according to a Scottish capitalist.28 John Cromie of Draper Hill, south of Ballynahinch in County Down, was said to be producing perhaps five to six thousand pieces annually.29 Around Dromore other entrepreneurs were putting-out fine yarns for cambric weaving but they were selling in the market, unlike Cromie. It was said, too, that there was an extensive manufacturer about Belfast but no-one was able to inform the select committee whether he manufactured linen or linen and cotton ‘unions’.30

The most obvious reason for capitalists to put-out yarn to weavers would have been to benefit from the production of mill-spun yarn, whether manufactured locally or in Britain. A major obstacle to the development of such a system, however, was claimed to be the imposition of considerable duties on imported flax and yarn for the protection of the Irish domestic yarn industry.31 The other reason given is even more significant for our understanding of the trade. Mill-spun yarn was too coarse for weaving the fine linens produced in the linen triangle. As Robert Williamson, a bleacher from Lambeg near Belfast, explained to the select committee:

Mill-spun yarn is generally adapted to the heavier fabrics … and it is more capable of being bleached before it is woven; it is adapted to what we call ducks, which are worn in trowsers [sic], etc. to heavy diapers; to heavy damask diapers; to dowlases and different articles of that heavy kind. The hand-spun yarn is adapted to very various sorts of linen; the best indeed is fitted pretty well for those things just enumerated; but it is peculiarly adapted to the very finest linen, up as high as twenty-seven hundreds; it is peculiarly fitted for the shirting that you wear; it is adapted to lawns, and to the finest damasks; to the very lowest thin three-fourth [i.e. 27 inches] wides exported to the Brazils, Mexico, Peru, and other places in South America, and the United States; besides, the spinning of this yarn affords the chief employment to the female population of Ireland.32

In substantial agreement with Williamson was the evidence of John Marshall of Leeds, the pioneer and leading figure in the mill-spinning of flax. He admitted that the yarn he spun would not be suitable for anything finer than the middle quality of Irish shirtings. He admitted also that machine yarn was more expensive than Irish hand-spun yarn of similar weight by from 10 to 15 per cent; as a result his sales to Ireland were small.33 In fact, in the year 1822 almost no mill-spun yarn was imported into Belfast.34 Nor was mill-spun yarn produced on any scale in Ulster by 1821, although 13 dry-spinning mills had been built in Ulster in 1805–9, with financial assistance from the Linen Board, to provide sail-cloth and canvas for the navy in the Napoleonic Wars.35 The late Rodney Green argued that ‘even before the wet-spinning system developed, large scale manufacturers of linen had appeared in County Down using millspun yarn imported from England’.36 Although he cited several firms engaged in putting-out yarn, however, his sources are government reports of 1836 and 1840 respectively, subsequent to the introduction and rapid expansion of the wet-spinning process: by 1839 there were 35 wet-spinning mills in Ulster employing 7,768 workers.

Why was there such a critical difference between Gill’s concept of the structure of the linen industry and the actual evidence presented to the select committee of 1825? The fundamental reason appears to have been Gill’s presumption that the industry was evolving from a domestic to a putting-out system. This led him to view the conflict between the drapers and weavers in the linen triangle in the 1750s and early 1760s as the weavers’ defence of their economic independence (in which light they certainly viewed it before 1764) and their refusal to accept the role of wage-earners.37 This was a serious misconception. Examination of the background to the dispute, and the failure to enforce a series of regulating acts for the inspection of ‘brown’ linens, reveals that the real intention of the drapers and bleachers in obtaining the comprehensive legislation of 1764 had been to impose certain standard practices in the manufacture and marketing of linens that would make it possible for them to purchase linens in the public markets. They believed that the system of public markets provided them with the most practical and efficient method of obtaining the linens they required, if only they could be certain that the quality of the cloth was uniform throughout each piece and its minimum measurements guaranteed.38

In 1762 the Linen Board, under an act of 1733, appointed ‘brown’ sealmasters to execute these duties in each market, and it was their roles that were confirmed by the act of 1764 (3 Geo. III, c. 35). What surprised everyone was the readiness of the Board to appoint weavers as brown sealmasters: indeed, within a few weeks nearly 1,300 seal-masters had been appointed.39 The fact that the Board was prepared to permit responsible weavers to seal their own linens as well as performing the duties of public sealmasters was practical as well as magnanimous. It made them partners in the promotion of standards while permitting them to collect fees for sealing from their fellow-weavers, at no charge to the Board. The sealmasters themselves were constantly reminded of their responsibilities by their seals on which their names were engraved; dereliction of duty could mean confiscation of the seals and public disgrace. For its part the Board, if it felt that standards were being allowed to deteriorate, could intervene to tighten them. In 1782, for example, when it was being suggested that ‘frauds in the sale of brown linens, whereby bleachers and drapers are often imposed on’ were becoming too frequent, the Linen Board appointed county inspectors under the control of two inspectors-general, one for Ulster and one for the other provinces. These county inspectors or their deputies were required to visit markets, intervene in disputes, and report faults in sealing to a magistrate. They were nominated by the registered bleachers of each county but selected by the Linen Board.40 They were encouraged in their supervisory role by local trustees of the Board and the linen drapers. In 1800 an address from the linen drapers to the Marquess of Downshire returned him ‘our most unfeigned acknowledgements for the important services you have rendered to the trade, by your incessant exertions to reform and re-establish the original system of brown-sealing — a system under which the great staple of Ireland has been so eminently prosperous’. His reply contained the sentence: ‘I am sensible that the brown seals were of the greatest advantage when first established, and I trust will continue to be so by their general use, if by your assistance the Linen Board shall be enabled to correct any abuse that may by negligence or fraud creep into the institution.’41

The relevance of this scheme even in 1825 was reflected in the number of brown sealmasters then operating throughout Ulster (Table 11.1). Within the counties of Antrim, Down and Armagh 12 linen markets were served by 386 manufacturers and others holding seals and only one public sealmaster; throughout the rest of Ulster there were 43 sealmasters and only five manufacturers serving 40 markets. The term ‘manufacturer’ was defined by a witness to the 1822 select committee examining the laws that regulated the linen trade in Ireland:

Number of brown linen sealmasters in the service of the Linen Board of Ireland, 1825

| County | Public sealmasters | Manufacturers and others holding seals |

Total |

| Antrim | 1 | 99 | 100 |

| Armagh | 0 | 150 | 150 |

| Down | 0 | 137 | 137 |

| Tyrone | 19 | 0 | 19 |

| Londonderry | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Donegal | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Monaghan | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Cavan | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Fermanagh | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| ULSTER | 44 | 391 | 435 |

| Louth | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| King’s County | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Longford | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Westmeath | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| LEINSTER | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Cork | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Clare | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Kerry | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Limerick | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Tipperary | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| MUNSTER | 18 | 0 | 18 |

| Mayo | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Roscommon | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Sligo | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Galway | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Leitrim | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| CONNACHT | 24 | 0 | 24 |

| IRELAND | 95 | 391 | 486 |

Source: Report from the Select Committee on the Linen Trade of Ireland (British Parliamentary Papers 1825 (463) V), p. 811.

The word ‘manufacturer’, to one unacquainted with the distinctions that exist among the trade, would seem to embrace every description of person that works at the loom, whereas it means … the very reverse of this. It is the distinguishing appellation of him ‘who does not work at the loom himself, but who buys his yarn and gives it out to weavers employed by him to be woven into cloth, which he sells himself in the public market’.

In discussing the importance of these individuals with a view to assessing them as influential sealmasters, it was reckoned that the number of clients was related to ‘the fineness or coarseness of the linen of the district in which they speak; thus in Belfast and Lisburn it was “five looms, or any greater number;” in Banbridge “ten looms and upwards;” and in Armagh, “twenty looms and upwards”’. These individuals might influence the bleachers but certainly not dictate to them. Their significance in society, however, was recognised. They were said to be ‘men of as high character, as respectable a station in life, and of as much wordly substance, as many to whom they sell their linens; they form that link in the chain of society that in England is called its “yeomanry”’.42 It was these manufacturers who gave the linen triangle its distinctive character within the brown linen trade. They were the men who employed other weavers, whether journeymen, cottiers, or members of their family. Yet it should be noted that each of them employed relatively few men, particularly in the Belfast, Lisburn and Banbridge areas where the finest linens were woven. The fundamental point, of course, is that these manufacturers sold their linens in the public market and the bleachers bought them there.

The pre-eminence of the brown linen markets in the structure of the trade can best be illustrated from two reports to the Linen Board, prepared in 1816 and 1821 by its secretary, James Corry.43 For the several markets in 1816 detailed replies to a circulated list of questions were provided by the inspectors. The information includes the kinds of cloth brought for sale, with the prices they fetched, the average number of webs sold on each market day, the average number of weavers attending each market, and the names of the principal buyers who attended, whether from far afield or locally, with an indication of their place of origin.44 The 1821 report is rather more limited, but as well as estimates of the number of weavers in both ‘slack time’ and ‘busy time’ it gives details of the number of pieces sealed in 1820 with an estimate of their value by the public sealmasters. It should be remembered that in the counties of Antrim, Armagh and Down the great bulk of the linens was measured by manufacturers holding brown seals and so for these counties the figures for the pieces sealed are crude estimates: this accounts for the most significant discrepancies between the two reports, the numbers of pieces reported as sold in the counties of Antrim and Armagh. The statistics for sales in the other counties are much more consistent and they emphasise the considerable scale of the markets in Tyrone, Londonderry and Monaghan by 1820 (Table 11.2).

In view of the differences between the 1816 and 1820 figures for the individual counties it is a mere coincidence that the total number of pieces sold weekly in these two years approximates to 24,000 in each case. For the year 1820 an analysis of the pieces sealed indicates that the markets handled about 43 million yards, approximately the same amount that was exported in the year ending 5 January 1821. Any estimate of total home production would have to take into account quality linens that did not go through the public markets, production in the other provinces, and linens that were retailed locally, usually by dealers, without coming to the public market. The poor quality of this latter class provoked the following comment from Belfast in the 1816 Report:

All linens brought to the Linen Hall come in the brown state; but many other descriptions are brought grey; half-white, etc. for the use of the common people, who loudly complain of the rotten state of the linens retailed in a grey state in the streets, alleging that they give no wear from being bleached with lime.45

Table 11.2. Average attendance and sales at brown linen markets in 1816 and 1820

| County | 1816 Weavers |

Pieces | 1820 Weavers |

Pieces | 1820 Length in yards sold annually |

| Antrim | 3,400-3,700 | 5,960-5,970 | 1,540-3,270 | 3,225 | 5,161,710 |

| Armagh | 1,050 | 4,290 | 1,500-2,900 | 7,796 | 15,613,800 |

| Down | 1,309-1,319 | 2,058-2,060 | 810-2,050 | 2,543 | 3,289,750 |

| Monaghan | 1,080 | 2,910 | 930-1,740 | 2,291 | 3,109,444 |

| Cavan | 750 | 1,150 | 510-930 | 934 | 2,251,545 |

| Fermanagh | 150 | 200 | 750-1,440 | 183 | 613,800 |

| Tyrone | 3,712-3,720 | 4,740 | 2,270-4,260 | 3,552 | 8,314,366 |

| Donegal | 174 | 174 | 130-250 | 200 | 626,680 |

| Londonderry | 2,750 | 2,800 | 1,950-3,570 | 3,642 | 4,169,984 |

| TOTAL | 14,375-14,693 | 24,282-24,294 | 10,390-20,410 | 24,366 | 43,151,079 |

Source: Tour of Inspection through Ulster 1816 (Dublin, 1817); J. Horner, The Linen Trade of Europe (Belfast, 1920).

When these reports for 1816 and 1820 are compared with those for 1784 and 1803 four distinct regions can be defined, specialising in various widths and qualities of cloth. This makes it possible for us to understand how a significant increase in production was achieved in the period between 1790 and 1825, in spite of the defection of many weavers and spinners to the cotton industry in the Belfast region. These regions were also being affected in different ways by competition that was forcing down profits to dangerously low levels.

The heart of the industry was concentrated within the triangle between Belfast, Dungannon, and Newry where the finest yard-wide linens were produced. They were bought in the markets at Belfast, Lisburn, Lurgan, Banbridge, Newry and bleached in the valleys of the Lagan and Upper Bann. The manufacture of cambrics was noted in Lurgan in 1784 and by 1803 it had spread to the neighbouring towns of Lisburn, Banbridge, Tandragee and Dromore.46 It is said to have declined after the French wars in face of competition from that country,47 but the 1816 report notes that the fine lawns were used for printed pocket handkerchiefs and children’s wear. The fine linens were popular in Britain for apparel while diapers were sold for towels and tablecloths.

This region must have suffered most by competition for weavers from the cotton industry thriving all round the shores of Belfast Lough, especially when cotton weaving was paying twice as much as linen. We do not know if the success of cotton weaving was responsible for compelling the linen drapers to concentrate on the more expensive linens. The linen triangle seems to have generated its own momentum:

In the north of Ireland … the object of every person who has flax, is to have it of as fine quality as he can; and the spinner’s object is to spin it as fine as they can, because it pays a better price; and the manufacturer’s object is to weave the finest linen that he can; for which reason, the coarse article in the north of Ireland is made only of the refuse of the flax.48

To the south of the linen triangle the yard-wide linens were mainly coarser and cheaper and known as ‘Stout Armaghs’. This district comprised south Armagh and Monaghan as well as Cootehill in County Cavan, famous for its sheetings. The city of Armagh was the centre of the industry and was by 1820 much the busiest linen market in Ulster. Yet much of the linen it handled was at the bottom end of the market. Although it was estimated that 6,000 webs a week (or 312,000 per year) were sold in Armagh in 1820, half of them were double pieces (52 yards long compared with about 25 yards), amounting to some eight million yards and sold at 5d. or 6d. per yard. They were woven from tow yarn (made from the fibres combed away during the preparation of the flax for spinning) and exported to England, either half-bleached or in their natural state. In the term used above they were made from ‘the refuse of the flax’. This indicates that south Armagh and Monaghan must have been selling much of its flax yarn, probably for export through Newry, Dundalk, or Drogheda, or perhaps to the linen triangle, if it was sufficiently fine for its weavers, leaving the tow yarn only for the local industry. This was a serious indication of the poverty of the local industry. A Scots employer who had toured Ulster and was giving evidence to the 1825 commission calculated that weavers of the cheap cloth that he saw in Monaghan market could earn no more than 2s. 6d. per week, working for twelve hours each day.49

The part of County Antrim that lay to the north of Lough Neagh had for many decades been the home of the three-quarter (yard) wide linens, with Ballymena as its capital and Ballymoney and Portglenone as the other significant markets. These ‘three-quarters’ were coarse linens for general use, often made from tow yarn, and fetched low prices: they appear to have been made mainly by farmers weaving in their spare time. As a consequence the Ballymena and Portglenone markets attracted many such part-time weavers from the neighbouring counties of Tyrone and Londonderry. During the early decades of the nineteenth century this region was penetrated by drapers purchasing yard wides and ‘seven-eights’ yard wides in Ahoghill and Ballymena. Ballymoney, however, was said to have lost a growing market in seven-eights to Coleraine.

The most interesting developments throughout the final fifty years of the domestic spinning industry were taking place in the west of the province, stretching from Inishowen in the north to Cavan in the south. Early in the eighteenth century the Linen Board had bestowed the name ‘Coleraines’ on a ‘seven-eights’ linen.50 Later it was applied specifically to cloth of this width woven from half-bleached yarn and suitable for good quality shirts. This marked the top end of the scale. The chief markets were Derry, Coleraine and Limavady (which collapsed before 1816), Strabane and Newtownstewart. It is probable that the making up of shirts in this region developed with this specialisation. Towards the south the quality tended to decline somewhat so that the linens were referred to first as ‘Moneymores’ and later as coarse and fine ‘Tyrones’. The greatest market was Dungannon, with Cookstown and Stewartstown to the north and Ballygawley, Fintona, Fivemiletown and Enniskillen to the west. For all this region the cloth was purchased by bleachers on the rivers Roe, Agivey, Moyola, and Ballinderry, and on the streams around Dungannon, because there were very few bleachgreens in the whole of the Foyle basin.

Demand from these bleachers stimulated production in the west of the province, especially in the counties of Donegal and Fermanagh. Whereas the report of 1784 notes that locally-made non-commercial ‘Laggans’ (from the traditional name of that district of east Donegal) were still being sold in the fairs, they had disappeared from sale in 1803 to be replaced by ‘seven-eights’ linens. The attraction of the Derry market was so strong, however, that the growing markets of Letterkenny and Ramelton found great difficulty in establishing themselves because of jobbers who flouted the laws. The appearance by then of ‘three-quarter’ webs woven from tow yarns in these markets as well as those of Derry, Strabane and Newtownstewart is an indication of the phenomenon explained by John McEvoy in 1802:

There cannot be a greater proof of the increase of the linen trade, than the great rise of flax land … now the same quantity of land frequently brings double that sum … Common labourers, who were not much in the habit of weaving some years ago, generally work out two or three yards of linen at night in the winter time, after the common day’s labour is over.51

In the south of the province Cavan, with its neighbouring counties of Longford and Leitrim, seems to have represented a world of its own. Even in 1784 its fairs and markets dealt in ‘seven-eights’, whereas both counties Monaghan and Fermanagh, and even the market at Cootehill in Cavan, dealt in ‘yards’: later Fermanagh went over to ‘seven-eights’. Markets at Killishandra, Ballinagh and Arva were frequented by local buyers with very few from Tyrone, Armagh and Monaghan. It may be that Cavan’s linen industry resembled that of Sligo, rather than that of Monaghan which was geared into Armagh.

The totality of the responses from these four regions to changing economic conditions in the early nineteenth century suggests how industrialisation and deindustrialisation occurred simultaneously in Ulster. If the Irish linen trade had been dependent on coarse linens it would have failed in competition with England and Scotland. Only in the linen triangle did weavers produce fine linens and so they were able later to use the fine yarns produced by the wet-spinning process. Elsewhere in the province the industry appears to have reached its maximum capacity by 1820, dependent as it was on the farmer/weaver economy. Competition from cotton was forcing down the market prices. To survive, families would economise more and more strenuously, exploit themselves, their children, their servants and their cottiers. They would depend more on a diet of potatoes. They would work longer hours in their own homes at the spinning wheel and the loom. Those who had access to land would farm it more intensively, leaving weaving to cottiers and landless labourers. The number of emigrants to Britain and North America would rise, draining away the younger folk and leaving the older generation to come to terms with change.

The linen trade in Ireland was especially vulnerable to the introduction of machine-spinning because it was immeshed in the social system, especially as that system was based on agriculture. An Irish linen merchant and bleacher, Robert Williamson, explained to the 1825 commission:

the linen trade is so constituted in Ireland and the capital so subdivided and spread abroad over the population, that the present mode is the best adapted to the circumstances of the country … In short, it is one of those already established things which you find as it is, and you are obliged to use the best means with respect to it in your power: to alter it (were it even desirable) you must re-cast the state of society and … re-model that of property. It is now a mixture of agriculture and manufacture, and I think it tends greatly to the health and morality of the people …52

Williamson, like many other Irish people, viewed the problem in social terms. He admitted that if machinery for spinning linen were to be introduced, it would throw the manufacture into the hands of large manufacturers. This development he would have welcomed. He was aware that Ireland was already losing several branches of the manufacture to the Scots, notably strong sheeting as in diapers, coarse damask diapers and dowlas, because the Scottish mill-spun yarn, although dear, was easier to bleach and more consistent in quality. Williamson was able to convince himself that the introduction of mill-spinning into Ireland would not destroy hand-spinning

because there is room enough for both, and the population, dense as it is, requires employment in both ways. Nor is it possible to direct capital generally over Ireland for mill-spinning; I should think that the new manufacture would rather fix itself in those portions of Ireland that are richest, and extend the other back to those unfortunate districts that have not the linen manufacture, or any other.53

Williamson underestimated the devastating impact that the introduction of mill-spinning had on those districts that had become almost dependent on the sale of fine hand-spun yarns to the triangle. They lost not only their markets but also their entrepreneurs. Only in a few places outside the triangle would linen spinning mills be erected and yarn put out to weavers, notably at Castlewellan, Keady, Laragh near Castleblaney, and Sion Mills near Strabane.

Williamson’s mention that a number of individuals had set up a subscription of £30,000 to erect a flax-spinning mill near Belfast predates Kay’s invention of the wet-spinning process in the same year.54 It suggests that Ulster capitalists were preparing to invest in machinery for dry-spinning rather than concede the industry to their English and Scottish competitors.

This study has argued that the pattern of the domestic linen trade in Ulster on the eve of the mechanisation of spinning had developed in the first half of the eighteenth century and was confirmed by an act of 1764 that specified that all brown linens had to be exhibited and sold in public markets after being measured and sealed by sealmasters licensed by the Linen Board. The movers of this act were the bleachers who believed that their interests would be best served if they or their agents were able to tour the linen markets to make a selection of those kinds and qualities of linens that they required to fulfil their contracts abroad. For this they needed an assurance that the quality and length of the linens were guaranteed. As we have seen, the bleachers were not anxious to become involved in dealing in yarn or putting-out work to weavers. Instead they made themselves an international reputation and attracted bleaching business from Britain and the Continent. Where a ‘putting-out’ system developed it was within the manufacturing process, but even there it was the rare individual who could command more than a score of looms.

Because the brown linen markets witnessed the transfer of all linens of commercial quality from the manufacturers to the finishers, the evidence of the four reports deserves proper consideration and analysis. The reaction of the four major regions throughout the period 1784–1820 to changing economic and social conditions provides valuable indications to the study of Ulster provincial society. Pat Hudson’s agenda for research challenges us to re-examine the evidence. We now have sufficient evidence to understand how the manufacture locked in with the agrarian base through the seasons and between regions, and we know something about the institutional environment of landholding.55 About both inheritance practices and the distribution of wealth much could be learned from analysis of the wills held in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, especially if they were related to the estate-archives there and to the Registry of Deeds material in Dublin.56 Although very little research has yet been done on the nature of central and local government, there is sufficient archive material available from parish vestries, manor courts, grand juries, and even borough corporations to devise worthwhile projects.57 The same can be said for the study of urban centres on the lines suggested by Leslie Clarkson’s work on Armagh city.58 Investigation into the history of Belfast will be boosted by the prospect of access to the computerised files of the Belfast News-Letter for the late eighteenth century. As for the major theme of the impact of proto-indus-trialisation on the family in Ireland, pioneer work has been done by Brenda Collins and Leslie Clarkson.59 To co-ordinate this research we need to create a forum where students from a variety of disciplines can share their ideas and learn about potential sources from archivists and librarians.

1 First published in Irish Economic and Social History XV (1988), 32–53.

2 Clarkson, L.A., Proto-Industrialization: The First Phase of Industrialization? (London, 1985).

3 Hudson, P., review of Clarkson, op. cit., in Economic History Review XXXIX (1986), 308.

4 Gill, Conrad, The Rise of the Irish Linen Industry (Oxford, 1925), p. 138.

5 Hudson, P., ‘Proto-industrialisation: the case of the West Riding wool textile industry in the 18th and early 19th centuries’, History Workshop 11 (1981), 37.

6 Thirsk, J. and Cooper, J.P. (eds), Seventeenth-Century Economic Documents (Oxford, 1972), pp. 302, 303; see pages 9 to 13.

7 See pages 24 to 48.

8 See pages 65 to 66.

9 Young, A., Tour in Ireland, ed. Hutton, A.W. (2 vols, London, 1892), vol. 1, 130.

10 See pages 39 to 48.

11 Gill, op. cit.

12 Ibid., pp. 144, 162, 279. The figures for 1770 (pages 144, 162) do not tally.

13 Lewis, E., ‘An eighteenth-century linen tablecloth from Ireland’, Textile History (1984), pp. 235–44.

14 Gill, op. cit., pp. 272, 273 (my italics). See also pages 144–5.

15 Harris, W., The Antient and Present State of the County of Down (Dublin, 1744), p. 108; Kelly, J. (ed.), The Letters of Lord Chief Baron Edward Willes (Aberystwyth, 1990), pp. 31, 33; Crawford, W.H. and Trainor, B. (eds), Aspects of Irish Social History 1750–1800 (Belfast, 1969), p. 92; Arthur Young confirms these trends in the late 1770s in his Tour, vol. 1, 120, 128, 150.

16 Gill, op. cit., p. 272.

17 Ibid., p. 155.

18 Ibid., 38–9; 3 Geo. III, c. 34, s. 49 re sales of linen yarn and cloth.

19 See pages 24–37, 185–8.

20 L’Amie, A., ‘Chemicals in the eighteenth-century Irish linen industry’ (MSc thesis, Queen’s University, Belfast, 1984).

21 Gribbon, H.D., The History of Water Power in Ulster (Newton Abbot, 1969), p. 87; PRONI Foster–Massereene Papers, D562/6225, Printed copy of John Greer’s 1784 Report of the State of the Linen markets in the Province of Ulster, with manuscript notes on the comparative state of the trade in 1803: published here as Appendix 4.

22 Report from the Select Committee on the Linen Trade of Ireland (British Parliamentary Papers 1825 (463) V) [hereafter 1825 Linen Trade Report].

23 Ibid., 731 (my italics).

24 Ibid., 741, 747, 790, 830.

25 1825 Linen Trade Report, 741.

26 If 400 weavers were to bring only one piece each it would take a maximum of 60 of these ‘rich manufacturers’ to bring the remaining 600 pieces. Minutes of the Trustees of the Linen and Hempen Manufactures of Ireland, containing the Reports of their Secretary, on a Tour of Inspection through the Province of Ulster in October, November, and December, 1816 (Dublin, 1817) [hereafter 1816 Tour Report], Appendix, 78.

27 1825 Linen Trade Report, 741, 745.

28 Ibid., 765.

29 Ibid., 792.

30 Ibid., 765, 792.

31 Ibid., 802–3.

32 Ibid., 791.

33 Ibid., 708, 709.

34 National Library of Ireland, MS 376, ‘Volumes of Dublin Imports and Exports’ which contain the statistics for all the individual Irish ports, 1822.

35 Gribbon, op. cit., pp. 92–3.

36 Green, E.R.R., The Industrial Archaeology of County Down (Belfast, 1963), p. 6.

37 Gill, op. cit., pp. 138–48.

38 Royal Irish Academy, Haliday Collection, vol. 308, no. 2, A Review of the Evils that have prevailed in the Linen Manufacture of Ireland (Dublin, 1762), pp. 9–23. This pamphlet refutes Gill’s comments that the linen drapers had not tried to enforce the existing laws: see Gill, op. cit., pp. 106–10.

39 Gill, op. cit., p. 115.

40 Ibid., pp. 207–8.

41 Belfast News-Letter, 18 February 1800.

42 Report from the Select Committee on the Laws which Regulate the Linen Trade of Ireland (British Parliamentary Papers 1822 (560), VII) [hereafter 1822 Linens Laws Report], 493–4.

43 Horner, J., The Linen Trade of Europe (Belfast, 1920), pp. 188–96.

44 1816 Tour Report, Appendix, pp. 29–30.

45 Ibid., Appendix, p. 77.

46 See note 20 and Appendix 4.

47 1825 Linen Trade Report, 802.

48 1822 Linen Laws Report, 486.

49 1825 Linen Trade Report, 763. See also appendix 5.

50 9 Anne, c. 3, s. 68.

51 McEvoy, J., Statistical Survey of the County of Tyrone (Dublin, 1802), p. 135.

52 1825 Linen Trade Report, 790.

53 Ibid., 791.

54 Ibid., 792.

55 Crawford, W.H., ‘Landlord–tenant relations in Ulster 1609–1820’, Irish Economic & Social History 2 (1975), 5–21; Roebuck, P., ‘Rent movement, proprietorial incomes and agricultural development, 1730–1830’, in Roebuck, P. (ed), Plantation to Partition (Belfast, 1981), 82–101; Wylie, J.C.W., Irish Land Law (London, 1975).

56 See for example the will of Thomas Christy of Moyallen, County Down, linendraper, 19 January 1780, in Crawford and Trainor, op. cit., pp. 70–71; Eustace, P.B. (ed.), Abstracts of Wills in the Registry of Deeds Dublin, vol. I: 1708–45; vol. II: 1746–85 (Dublin, 2 vols, 1954–6).

57 Crawford and Trainor, op. cit., pp. 122–32; [Crawford, W.H.], Sources for the Study of Local History in Northern Ireland (Belfast, 1968).

58 Clarkson, L.A., ‘An anatomy of an Irish town: the economy of Armagh, 1770’, Irish Economic & Social History 5 (1978); ‘Household and family structure in Armagh City, 1770’, Local Population Studies XX (1978); ‘Armagh 1770: portrait of an urban community’, in Harkness, D. and O’Dowd, M. (eds), The Town in Ireland (Belfast, 1981).

59 See especially Collins, B., ‘Proto-industrialization and pre-Famine emigration’, Social History VII, 2 (1982), 127–46.