IN SEPTEMBER OUR ARMIES WERE CROWDING UP against the borders of Germany. Enemy defenses were naturally and artificially strong. Devers’ U. S. Seventh and French First Armies were swinging in eastward against the Vosges Mountains, which formed a traditional defensive barrier. In the north the Siegfried Line, backed up by the Rhine River, comprised a defensive system that only a well-supplied and determined force could hope to breach.

For the moment we were still dependent upon the ports at Cherbourg and Arromanches, and because of their limited capacity and the restricted communications leading out of them the accumulation of forward reserves was impossible. It was even difficult to maintain adequately the troops that were daily engaged in constant fighting for position along the front. This would continue to be true until we could get Antwerp and Marseille working at capacity. Of the former, Bradley wrote to me on September 21: “… all plans for future operations always lead back to the fact that in order to supply an operation of any size beyond the Rhine, the port of Antwerp is essential.”1 He never failed to see that logistics would be a vital factor in the final defeat of Germany.

With the advent of bad weather, road maintenance presented additional problems to the Services of Supply because of the shallow foundations of many of the European roads, particularly in Belgium. In numerous instances our heavily laden trucks broke completely through the surfaces of main highways and it seemed almost impossible to fill the resulting quagmires with sufficient stone and gravel to restore them to a semblance of usefulness.

To reduce dependence on roads we brought in quantities of railway rolling stock to replace that destroyed earlier in the war.2 To do this expeditiously, railway engineers developed a simple scheme that was adopted with splendid results. Heavy equipment like railway cars can normally be brought into a theater only at prepared docks. Unloading is laborious because of the need for using only the heaviest kind of cranes and booms. Our engineers, however, merely laid railway tracks in the bottom of LSTs. They then laid railway lines down to the water’s edge at the beaches of embarkation and debarkation and, by arranging flexible connections between ground tracks and those in the LSTs, simply rolled the cars in and out of the ships. But while waging and winning, during the autumn months, the battle of supply, we found no cessation of fighting along the front.

Our ground forces, while not yet at peak strength, continued constantly to increase. On August 1 our divisional strength on the Continent was thirty-five, with four American and two British divisions in the United Kingdom. By October 1 our aggregate strength on the Continent, including the Sixth Army Group which had advanced through the south of France, was fifty-four divisions, with six still staging through the United Kingdom.3 All our divisions were short in infantry replacements, and in total numerical strength of ground forces the Germans still had a marked advantage. We were disposed along a line which, beginning in the north on the banks of the Rhine, stretched five hundred miles southward to the border of Switzerland. To the south of that country detachments were posted on the French-Italian border to guard against raids on our lines of communication by the Germans in Italy.

This meant that, counting all types of divisions—infantry, armored, and airborne—we could, on the average, deploy less than one division to each ten miles of front.

In view of all these conditions there was much to be said for an early assumption of the defensive in order to conserve all our strength for building up the logistic system and to avoid the suffering of a winter campaign. I declined to adopt such a course, and all principal commanders agreed with me that it was to our advantage to push the fighting.

One important consideration that indicated the advantage of keeping up our offensives to the limit of our troop and logistical capacity was the knowledge that in order to replace his great losses of July, August, and September the enemy was hastily organizing and equipping new divisions. In many instances he was compelled to bring these troops into the lines with but sketchy training. Initially they had a low order of efficiency, and attacks against them were far less costly than they would become later as these new enemy formations succeeded in perfecting their training and their defensive installations.

Intelligence agencies were required to make exhaustive daily analyses of enemy losses on all parts of the front. The purpose was to avoid attacks in those areas where the balance sheet in losses showed any tendency to favor the enemy. During this period we took as a general guide the principle that operations, except in those areas where we had some specific and vital objective, such as in the case of the Roer dams, were profitable to us only where the daily calculations showed that enemy losses were double our own.

We were certain that by continuing an unremitting offensive we would, in spite of hardship and privation, gain additional advantages over the enemy. Specifically we were convinced that this policy would result in shortening the war and therefore in the saving of thousands of Allied lives.

Consequently the fall period was to become a memorable one because of a series of bitterly contested battles, usually conducted under the most trying conditions of weather and terrain. Walcheren Island, Aachen, the Hurtgen Forest, the Roer dams, the Saar Basin, and the Vosges Mountains were all to give their names during the fall months of 1944 to battles that, in the sum of their results, greatly hastened the end of the war in Europe. In addition to the handicap of weather there was the difficulty of shortages in ammunition and supplies. The hardihood, courage, and resourcefulness of the Allied soldier were never tested more thoroughly and with more brilliant results than during this period.

The strength of our growing ground force was multiplied by the presence of a powerful and efficient air force.

Tactically, an air force possesses a mobility which places in the hand of the high command a weapon that may be used on successive days against targets hundreds of miles apart. Aerial bombardments are delivered in such concentrated form as to produce among defending forces a shock that is scarcely obtainable with any amount of artillery.

For pinpointing of accessible targets, the air was normally not so effective as artillery. Moreover, against general targets, air power did not destroy—it damaged. An industrial area was never eliminated by a single raid and, indeed, rarely obliterated beyond partial repair even by repeated bombings. Lines of communication were never, except in extended periods of good weather, completely severed beyond any hope of use. But the air did deplete the usefulness of anything it attacked and, given ideal flying conditions and when used in large concentrations, could carry this process of depletion to near perfection.

Air attack by a single combat plane is a fleeting thing, and the results achieved do not always conform to first estimates. Air reports of destroyed vehicles, particularly armored vehicles, were always too optimistic by far. This was not the fault of pilots. Each fighter-bomber airplane was equipped with a movie camera which automatically recorded the apparent results of every attack. The films were examined at bases and became the basis of “Air Claims,” but we found that this method provided no accurate estimate of the damage actually inflicted. Exact appraisal could be made only after the area was captured by the ground troops.

For the delivery, in a single blow, of a vast tonnage of explosives upon a given area, the power of the air force is unique. Employment of large bombers in this role has the advantage of imposing no strain upon the forward lines of communication. Every round of ammunition that is fired from an artillery shell is unloaded at a main base and from there progresses to the front over crowded rail and road lines. After several handlings it is finally available for use at the gun site. The big bombers are stationed far in the rear; in our case they were in the United Kingdom. The bombs they used were either manufactured in that country or brought over from the United States in cargo ships. From factories or ports they went to appropriate airfields, and from there were delivered in one handling directly against the enemy.

The air can be employed in a variety of ways to forward the progress of the land battle. Its most common functions are to prevent interference with our ground forces by enemy airplanes, to render tactical assistance to attacking troops by fighter-bomber effort against selected targets on the front, and to facilitate capture of strongly defended points by heavy bombardment. In these close-support activities it has, of course, certain limitations. In Europe bad weather was the worst enemy of the air, and the unexpected advent of rain, fog, or cloud often badly disarranged a battle plan. In the middle of December bad weather prevented the air from discerning the concentration of unused German strength in the Ardennes, and made the air force of little use to us in the first week of that battle. Moreover, by its nature, the air cannot stay constantly at the front; each plane must return periodically to its base for refueling and servicing. This limited the number present at the front to a fraction of the total numbers available. Occasionally enemy planes could therefore strafe our front lines, even though in over-all numbers our air strength was relatively overwhelming.

The air force had other important uses. One of these was to attack the enemy’s supply lines. Still another was that of increasing the decisiveness of the ground battle. Every ground commander seeks the battle of annihilation; so far as conditions permit, he tries to duplicate in modern war the classic example of Cannae. In the beginning of a great campaign, battles of annihilation are possible only against some isolated portion of the enemy’s entire force. Destruction of bridges, culverts, railways, roads, and canals by the air force tends to isolate the force under attack, even if the severance of its communications is not complete.

In the fall of 1944 our air strength, in operational units, including the associated bomber strength, was approximately 4700 fighters, 6000 light, medium, and heavy bombers, and 4000 reconnaissance, transport, and other types.4

While this build-up was proceeding during the fall months there was, as originally planned, much to be done operationally. In the north, besides capturing the approaches to Antwerp, it was desirable to make progress toward closing the Rhine, because it was from this region that our heaviest attacks would be launched in the crossing of that river. Farther south, on Bradley’s front, it was advantageous to conduct preliminary operations looking toward the final destruction of all German forces remaining west of the Rhine. Thus we would not only deplete the forces available for the later defense of the river but we would also secure the areas in the Saar region from which we planned to launch strong attacks in conjunction with those in the north, when we were ready to envelop the Ruhr.

In the fall fighting we again encountered our old enemy, the weather. The June storm on the beaches had established a forty-year record for severity. Again in the autumn the floods broke another meteorological record extending back over decades. By November 1 many of the rivers were out of their banks and weather conditions along the whole front slowed up our attacks. In spite of these conditions we proceeded with the general plan of building up great bases and communications to the borders of Germany, closing the Rhine with initial emphasis on the left, preparing for the destruction of the German forces west of the river, throughout its length, and getting ready to launch the final assaults toward the heart of Germany.

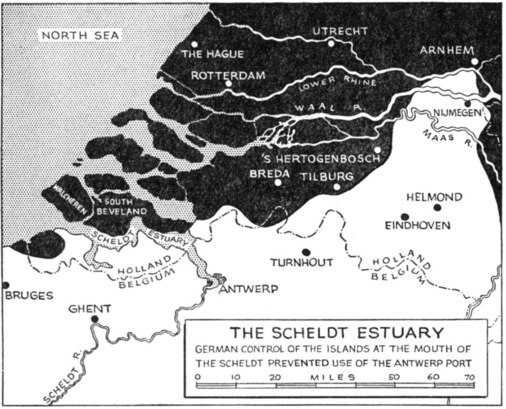

Capture of the approaches to Antwerp was a difficult operation. The Scheldt Estuary was heavily mined, and the German forces on Walcheren Island and South Beveland Island completely dominated the water routes leading to the city. It was unfortunate that we had not been successful in seizing the area during our great northeastward reach in the early days of September.

Reduction of these strongholds required a joint naval, air, and ground operation. Montgomery gave General Crerar of the Canadian First Army responsibility for developing and executing the plans.5 Preparatory work was started shortly after the city fell into our hands on September 4.

The only land approach to the hostile positions was by a narrow neck connecting South Beveland with the mainland, and the operation was worked out to include an attack westward along this isthmus, co-ordinated with an amphibious assault brought in by sea. The necessary forces for the attack could not be assembled until late October. If I had not attempted the Arnhem operation, possibly we could have begun the Walcheren attack some two or three weeks earlier.

To the Canadian 2d Division was assigned the job of entering the neck, and from there attacking westward along the isthmus against the Germans on South Beveland. The troops were frequently forced to fight waist-deep in water against strong German resistance and it took them three days to reach the west end of the isthmus. But by October 27 the division had established itself on the island proper. The British 52d Division was landed on the south shore of South Beveland on the night of October 25–26. The two forces then fought forward in a converging attack to a juncture and by the thirtieth of the month South Beveland was entirely in our possession.

The defending garrison on Walcheren Island consisted of the troops that had escaped from South Beveland and of detachments from the German Fifteenth Army, which had originally been stationed in the Calais area.

The amphibious assault against Walcheren, on November 1, was carried out against some of the strongest local resistance we met at any coast line during the European operation. To provide supporting fire, only small naval vessels could be used but these unhesitatingly pushed in close to the Walcheren Island shore and persistently engaged heavy land batteries in order to assist the troops going ashore. Losses among the naval vessels were abnormally high but the courage and tenacity of the crews were responsible both for the successful landing and for minimizing losses among assaulting personnel.

A feature of this difficult campaign was a novel employment of big bombers to blow up portions of the dikes that held back the sea from the lower levels of the island. These breaches, permitting the sea to flood critical sections of the defenses, were of great usefulness in an operation that throughout presented unusual difficulties.6

Final German resistance on the island was eliminated by November 9, by which time some 10,000 enemy troops had been captured, including a division commander. The cost was high. For the entire series of operations in the area our own casualties, almost entirely Canadian and British, numbered 27,633. This compared to less than 25,000 in the capture of Sicily, where we defeated a garrison of 350,000.7

With this effort accomplished, we began the clearing of mines from the Scheldt Estuary. As usual the Germans had installed their mines in great profusion and the job, in spite of unremitting work on the part of the Navy, required two weeks for completion.

The first ships to begin unloading in Antwerp arrived there November 26. The Germans had begun launching V-1 and V-2 weapons against the city in mid-October. While the bombs were frequently erratic, as they had been in London, the V-2s caused considerable damage in the district. Numbers of civilians and soldiers were killed and communications and supply work were often interrupted, although usually only for brief periods. The civilian population of Antwerp sustained these attacks unflinchingly. One V-2 bomb struck a crowded theater and killed hundreds of civilians and an almost equal number of soldiers.

The enemy also employed large numbers of E-boats (a small, speedy type of surface torpedo boat) and tiny submarines to interfere with our use of Antwerp. These weapons we countered by energetic naval and air action. In spite of all difficulties, Antwerp quickly became the northern bulwark of our entire logistical system.

While this spectacular and gratifying operation was in progress on the northern flank, the rest of the front was far from quiet. On the Twenty-first Army Group front Montgomery succeeded in concentrating enough strength so that on November 15, immediately following the fall of Walcheren Island, he undertook an eastward drive. Winter conditions were now approaching and his advances were made over difficult country, but by December 4 he had cleared out the last German pocket west of the Maas, the same river which, farther south in Belgium and France, is called the Meuse.

Because of the extended front held by the Twenty-first Army Group it was impossible at the moment to launch further strong offensives in that area. Montgomery’s army group had long since absorbed all the British Empire troops available in the United Kingdom, including the Canadian Army and the Polish division. Further reinforcement was impossible unless, as eventually happened, a few additional units could be brought up from the Mediterranean theater. The Americans were in a different position. Reinforcing divisions were rapidly coming from the United States, and as they reached the battle front they provided strength for the execution of important tasks and made it possible to broaden the American sector whenever necessary to provide opportunity for concentrations on the flanks.

Immediately south of the British area Bradley, on October 22, brought into line the U. S. Ninth Army under General Simpson.8 On November 16, Bradley renewed his offensive toward the Rhine in the northern part of his sector. The attack was carried out by the Ninth and First Armies and was preceded by a heavy bombing of the enemy and by artillery bombardment. Twelve hundred and four American and 1188 British heavy bombers participated, the operation being another example of the extent to which we were then using the heavy bomber to intervene effectively in the ground battle.9

These attacks initially employed fourteen divisions, and the number was soon increased to seventeen. Nevertheless, progress was slow and the fighting intense. On the right flank of this attack the First Army got involved in the Hurtgen Forest, the scene of one of the most bitterly contested battles of the entire campaign. The enemy had all the advantages of strong defensive country, and the attacking Americans had to depend almost exclusively upon infantry weapons because of the thickness of the forest. The weather was abominable and the German garrison was particularly stubborn, but Yankee doggedness finally won. Thereafter, whenever veterans of the American 4th, 9th, and 28th Divisions referred to hard fighting they did so in terms of comparison with the Battle of Hurtgen Forest, which they placed at the top of the list.10

In spite of numerous smaller battles of the same sanguinary character, in which units were pinned down for days as they dug out the defending garrisons, general progress continued until we reached the banks of the Roer River, where the Ninth Army arrived on December 3.

At the banks of the Roer we met a new kind of tactical problem. Farther up the river, at Schmidt, were great dams. They were of special defensive value to the German because, by operation of the floodgates in the dams, he could vary the water level below them. This made an immediate assault across the Roer River impossible, since any troops successful in crossing could be isolated by a flooding of the river and thereafter eliminated by the employment of German reserves.11

We first attempted the destruction of the dams by air. The bombing against them was accurate and direct hits were secured. However, the concrete structures were so massive that damage was negligible, and there was no recourse except to take them by ground attack. Because the dams were located in difficult mountain country the attack was certain to be slow and costly. After an attack by the 28th Division had failed to make satisfactory progress a heavy assault was started by the First Army December 13.

Meanwhile, south of the Ardennes Forest, the Third Army launched an attack on November 8. Its offensive was aimed generally at the Saar region and made excellent initial progress. North of Metz, bridgeheads were established across the Moselle, and shortly after the middle of November the leading troops crossed the German frontier. Metz was surrounded and cut off. The city surrendered November 22.12 However, some of the forts in the vicinity held out stubbornly and it was almost the middle of December before the final one was reduced and mopped up.

In the right sector of the Third Army the advance quickly brought us up against some of the strongest sections of the Siegfried Line, those guarding the triangle between the Moselle and the Rhine. In this region the Siegfried comprised two general lines of defenses. The forward one was a continuous system of obstacles and pillboxes, but was of no great depth. In the rear was another line, of extraordinary strength. It featured a series of field forts, mutually supporting, arranged in a line more than two miles deep. These defenses slowed up the advance of the Third Army, and since their reduction required a vast amount of heavy artillery ammunition, the attacks there were suspended until additional logistical support could be provided.

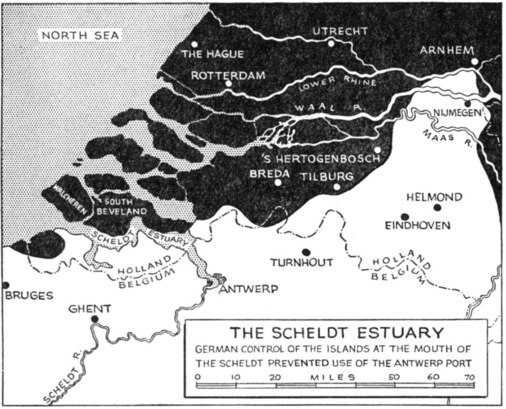

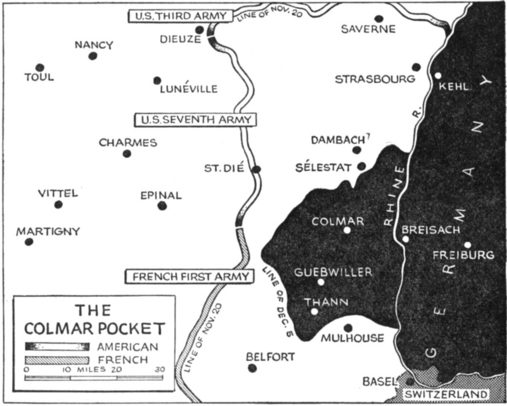

Still farther south there was much fighting in Devers’ Sixth Army Group. During September it advanced northward through the Rhone Valley and came in abreast of the Third Army line, facing eastward in the difficult Vosges Mountain area. Devers attacked that formidable barrier on November 14, in an attempt to penetrate into the plains of Alsace. Once we could secure this region Devers’ forces could concentrate the bulk of their strength on the left and the defenders of the Saar would have to resist powerful attacks on two fronts.

The French First Army led the attack on Devers’ front and breached the Belfort Gap within a week. Its leading troops quickly reached the Rhine. This turned the flank of the German position in the Vosges and forced a general withdrawal in front of the U. S. Seventh Army under General Patch. This force, attacking abreast of the French First Army, had found exceedingly tough going through the tortuous passes of the mountains. In Patch’s army Major General Edward H. Brooks’s VI Corps was on the right, and Major General Wade H. Haislip’s XV Corps, formerly with Patton, was on the left. When the German withdrawal started because of the French success, these troops made rapid progress. The U. S. 44th Division captured Saarebourg on the twenty-first, and on the twenty-second our troops broke out into the Rhine plain. Strasbourg, on the banks of the Rhine, was entered by the French 2d Armored Division on the twenty-second of the month. The enemy, as was his habitual practice, launched a counterattack almost instantly. Initially, our advancing troops lost some ground but the 44th Division fought off the enemy and regained its positions. The 79th Division now came abreast of the 44th and the two of them made rapid progress toward Haguenau, which they took on December 12.13

During the progress of these attacks I visited Devers to make a survey of the situation with him. On his extreme left there appeared to be no immediate advantage in pushing down into the Rhine plain. I directed him to turn the left corps of Patch’s army northward to bring it into line connecting with the right flank of Patton’s army, on the western slopes of the Vosges. That corps was to support the Third Army in its attacks against the Saar, which were soon to be renewed.

On the remainder of Devers’ front it was of course desirable to close up to the Rhine as rapidly as possible and then, by moving northward, to gain the river bank all the way northward to the Saar. However, I particularly cautioned Devers not to start this northward movement, on the east of the Vosges Mountains, until he had cleaned out all enemy formations in his rear.

Sometimes it is advisable to by-pass enemy garrisons and merely contain them until their isolation and lack of supply compel surrender. However, this procedure is normally applicable only if the enemy’s troops are completely surrounded. Moreover, the method always immobilizes a portion of our own troops and it is never applicable when the pocket is in an area which we must use for offensive purposes or from which it can threaten our communications. I had gotten tired of dropping off troops to watch enemy garrisons in the rear areas, so I impressed upon Devers that to allow any Germans to remain west of the river in the upper Rhine plain, south of Strasbourg, would be certain to cause us later embarrassment.

General Devers believed that the French First Army, which had operated so brilliantly in breaking through the Belfort Gap and reaching the Rhine, could easily take care of the remnants of the German Nineteenth Army still facing them in the Colmar area. In describing the situation to me he said, “The German Nineteenth has ceased to exist as a tactical force.” Consequently he estimated that he could carry out my instructions for the elimination of the Germans near Colmar without the assistance of General Brooks’s VI Corps. He had reason to feel justified in this estimate, particularly in view of the great defeats already inflicted on the German Army. He ordered the VI Corps to turn northward in the plain east of the Vosges, so that it could co-operate with the XV Corps, west of those mountains, in the attacks against the Saar.

Devers’ estimate of the French First Army’s immediate effectiveness was overoptimistic, while he probably underrated the defensive power of German units when they set themselves stubbornly to hold a strong position. The French Army, weakened by its recent offensive, found it impossible to eliminate the German resistance on its immediate front, and thus was formed the Colmar pocket, a German garrison which established and maintained itself in the defensible ground west of the Rhine in the vicinity of Colmar. The existence of this pocket was later to work to our definite disadvantage.14

The fighting throughout the front, from Switzerland to the mouth of the Rhine, descended during the late fall months to the dirtiest kind of infantry slugging. Advances were slow and laborious. Gains were ordinarily measured in terms of yards rather than miles. Operations became mainly a matter of artillery and ammunition and, on the part of the infantry, endurance, stamina, and courage. In these conditions infantry losses were high, particularly in rifle platoons. The infantry, which in all kinds of warfare habitually absorbs the bulk of the losses, was now taking practically all of them. These were by no means due to enemy action alone. In other respects, too, the infantry suffered an abnormal percentage of casualties. Because of exposure the cases of frostbite, trench foot, and respiratory diseases were far more numerous among infantry soldiers than others. Because of depletion of their infantry strength, divisions quickly exhausted themselves in action. Without men to carry on the daily task of advance and maneuver under the curtain of artillery fire our offensive strength fell off markedly.

Aside from the problem of depleted unit strength, we found it difficult to find enough divisions to perform all the tasks that required immediate attention and still maintain the concentrations required for successful attacks.

As the infantry replacement problem became acute we resorted to every kind of expedient to keep units up to strength. Full reports were made to the War Department so that effort in the homeland would be concentrated on this need. We combed through our own organization to find men in the Services of Supply and elsewhere who could be retrained rapidly for employment in infantry formations. Wherever possible we replaced a man in service organizations by one from the limited-service category or by a Wac.15 General Spaatz found that he could give us considerable help in this matter. Ten thousand men were transferred from his units to the ground forces. All these measures, however, failed to keep filled the ranks of the infantry formations. Realizing this, General Marshall sent me a suggestion that seemed to possess great merit. It was that the infantry of the trained divisions in the United States should be dispatched to us without waiting for the additional shipping needed to bring their artillery, trucks, and other heavy equipment. He and I hoped that in this way we could bring into line new regiments and give them valuable battle training by rotating them with the infantry of divisions already in the line. The principal purpose was to give the tired and depleted infantry of a veteran division opportunity to refit and rehabilitate itself while its place on the front was taken by one of the new full-strength regiments.16

In the outcome our hopes were not completely fulfilled. As the winter wore on our need for troops became so great and our long lines were so thinly manned that when the new regiments arrived each army commander frequently found it necessary, instead of replacing tired troops with the fresh ones, to assign a special sector to the new troops and to support them with such artillery from corps and army formations as he could scrape together for the purpose.

This situation was entirely unsatisfactory and a complete violation of the purpose for which the new regiments were rushed into the theater ahead of their heavy equipment. Nevertheless, the requirements of the front allowed us to do nothing else, and though wherever possible we returned to the original plan of rotation, we were never able to implement it in the manner intended. In the over-all result, however, the early arrival of these infantry units had a profound and beneficial effect. In particular crises of the campaign they allowed us to effect a concentration of veteran units which would otherwise have been impossible.

In both World Wars the infantry replacement problem plagued American commanders in the field. Only a small percentage of the manpower in a war theater operates in front of the light artillery line established by the divisions. Yet this small portion absorbs about ninety per cent of the casualties. Many of these casualties are soon fit to return to the front, but this creates another problem of great importance—particularly in maintaining morale.

Replacements, whether newly arrived from the homeland or recently discharged from hospitals, are normally processed to the front through replacement depots. Thus there is a great intermingling of veterans from numerous divisions and of others who have not seen action. When the need for replacements is acute, efficiency demands that all men available in depots be dispatched promptly to the place where most needed. Individual assignment according to personal preference is well-nigh impossible.

However, veterans always insist on returning to their own divisions, and when this cannot be done a definite morale emergency results. We tried, within the limits imposed by dire needs, to return veterans to their own units, but in emergency the rule had to be violated. In the fall of 1944 all such purposes had to be thrown overboard in the effort to supply men to the areas of most critical need.

Maintenance of morale was a problem of first importance. We had established a furlough plan which gave at least some men the opportunity to go back to Paris or London. We also established divisional centers in rear of the lines where a company or a battalion could occasionally get out of the fighting zone and the men could secure baths, warm beds, and a day or two of rest. In Paris we established an Allied Club in one of the city’s largest hotels. It was reserved exclusively for enlisted men and was one of the most successful activities we had for the benefit of men who got an opportunity to visit the city. We depended upon the Red Cross and the USO for civilian aid in the matter of recreation and entertainment.17

During World War I the American Army had received recreation and entertainment assistance from a variety of civilian organizations. They were effective, but the many administrative difficulties arising out of contacts with so many different groups led the War Department at the beginning of World War II to insist that this work should be handled by two principal agencies. These were, in the recreational field, the Red Cross and, in the entertainment field, the USO. The services of these devoted people to soldiers in the field were beyond praise. The Red Cross operated clubs and coffee and doughnut wagons; it sent visitors to hospitals, wrote letters, furnished friendly counsel; and all in all was as successful in providing an occasional hour of homelike atmosphere for the fighting men as was possible in an area thousands of miles from America.18

In the same way the USO succeeded in giving the soldier an occasional hour or two of entertainment which he never failed to appreciate. I have seen entertainers carrying on their work in forward and exposed positions, sometimes under actual bombing attack. In rest areas, in camps, in bases, and in every type of hospital they brought to soldiers a moment of forgetfulness which in war is always a boon.

In the late fall, as we approached the borders of Germany, we studied the desirability of committing our air force to the destruction of the Rhine bridges, on which the existence of the German forces west of the river depended. If all of them could be destroyed, it was certain that with our great air force we could so limit the usefulness of floating bridges that the enemy would soon have to withdraw. We entertained no hope of saving these bridges for our own later use. It was accepted that once the enemy decided that he had to retreat he would destroy all the bridges, and our arrival would find none standing, unless by sheer accident.

Our reasons for declining to commit the air force against the bridges were based upon considerations of priority and effectiveness. To destroy merely a few was of little use. A total of twenty-six major bridges, it was reported to me at that time, spanned the river; some twenty of them would have to be rendered useless or the effort would be only partially effective. Even with the best of flying conditions the task would require a prolonged and heavy bombing effort. But at that period of the year in Europe there rarely occurs a day of sufficiently good weather to allow pinpoint bombing from great heights, and enemy anti-aircraft was still so strong and so efficient that low-flying bombing was far too expensive. Consequently the only method we could employ against the bridges was blind bombing, through the clouds. The Air Staff calculated that destruction of the bulk of the bridges would require vastly more time and bomb tonnage than we could afford to divert from other vitally important purposes.19

THE RHINE BARRIER

ISOLATE, THEN ANNIHILATE

“… battles of annihilation are possible only against some isolated portion of the enemy’s entire force. Destruction of bridges, culverts, railways, roads, and canals by the air force tends to isolate the force under attack …” This page

Ulm Rail Yards After December 1944 Raid (illustration credit 17.1)

SUPREME OVER GERMANY

“By early 1945 the effects of our air offensive against the German economy were becoming catastrophic … there developed a continuous crisis in German transportation and in all phases of her war effort.” This page

Bremen Is Target of B-17 and B-24 Flight (illustration credit 17.2)

One of the greatest of these other purposes was to deplete Germany’s reserves of fuel oil. By this time the enemy was getting into precarious position with respect to this vital item of supply. The orders to the heavy bombers were to keep pounding all sources of oil, refineries, and distribution systems to the limit of their ability. This tactic had a great effect not only generally upon the entire warmaking power of Germany but also directly upon the front. Every German commander had always to calculate his plans in terms of availability of fuel, and it was to our advantage to keep pounding away to increase the enemy’s embarrassment.20

This air campaign against oil reserves tended to emphasize one of the great advantages we had enjoyed over the enemy in all the Mediterranean and European campaigning. It was in the matter of relative mobility. The American Army has always featured mobility in the organization and equipment of its forces. Before the advent of the motorcar our Army was proportionately stronger in cavalry than most other armies of the time. With the coming of the motor, the American Army eagerly seized upon it to gain added mobility. Our advantage in this direction was vastly increased by the mass production methods of American industry. There was certainly no other nation in the world that could have supplied, repaired, and supported the great fleet of motor transportation that the American armed forces used in World War II.21

Through late November and early December the badly stretched condition of our troops caused constant concern, particularly on Bradley’s front. In order to maintain the two attacks that we then considered important we had to concentrate available forces in the vicinity of the Roer dams on the north and bordering the Saar on the south. This weakened the static, or protective, force in the Ardennes region. For a period we had a total of only three divisions on a front of some seventy-five miles between Trier and Monschau and were never able to place more than four in that region.22 While my own staff kept in closest possible touch with this situation, I personally conferred with Bradley about it at various times. Our conclusion was that in the Ardennes region we were running a definite risk but we believed it to be a mistaken policy to suspend our attacks all along the front merely to make ourselves safe until all reinforcements arriving from the United States could bring us up to peak strength.

In discussing the problem Bradley specifically outlined to me the factors that, on his front, he considered favorable to continuing the offensives. With all of these I emphatically agreed. First, he pointed out the tremendous relative gains we were realizing in the matter of casualties. The daily average of enemy losses was double our own. Next, he believed that the only place in which the enemy could attempt a serious counterattack was in the Ardennes region. The two points at which we had concentrated troops of the Twelfth Army Group for offensive action lay immediately on the flanks of this area. One, under Hodges, was just to the northward; the other, under Patton, was just to the south. Bradley felt, therefore, that we were in the best possible position to concentrate against the flanks of any attack in the Ardennes area that might be attempted by the Germans. He further estimated that if the enemy should deliver a surprise attack in the Ardennes he would have great difficulty in supply if he tried to advance as far as the line of the Meuse. Unless the enemy could overrun our large supply dumps he would soon find himself in trouble, particularly in any period when our air forces could operate efficiently. Bradley traced out on the map the line he estimated the German spearheads could possibly reach, and his estimates later proved to be remarkably accurate, with a maximum error of five miles at any one point. In the area which he believed the enemy might overrun by surprise attack he placed very few supply installations. We had large depots at Liége and Verdun but he was confident that neither of these could be reached by the enemy.

Bradley was also certain that we could always prevent the enemy from crossing the Meuse and reaching the major supply establishments lying to the westward of that river. Consequently any such enemy attack, in the long run, would prove abortive.

Our general conclusion was that we could not afford to sit still doing nothing, while the German perfected his defenses and the training of his troops, merely because we believed that at some time before the enemy acknowledged final defeat he would attempt a major counteroffensive. Bradley’s final remark was: “We tried to capture all these Germans before they could get inside the Siegfried. If they will come out of it and fight us again in the open, it is all to our advantage.”

Both Bradley and I believed that nothing could be so expensive to us as to allow the front to stagnate, going into defensive winter quarters while we waited for additional reinforcements from the homeland.

The responsibility for maintaining only four divisions on the Ardennes front and for running the risk of a large German penetration in that area was mine. At any moment from November 1 onward I could have passed to the defensive along the whole front and made our lines absolutely secure from attack while we awaited reinforcements. My basic decision was to continue the offensive to the extreme limit of our ability, and it was this decision that was responsible for the startling successes of the first week of the German December attack.

In early December, General Patton, with his Third Army, was making preparations to renew the attack against the Saar, the assault to begin December 19. Patton was very hopeful of decisive effect; but, determined to avoid involvement in a long, inconclusive, and costly offensive, Bradley and I agreed that the Third Army attack would have to show tremendous gains within a week or it would be suspended. We knew of course that if it was successful in gaining great advantages the enemy would have to concentrate from other sectors to meet it, and therefore Patton’s success would tend to increase our safety elsewhere. On the other hand, if we should get a considerable number of divisions embroiled in costly and slow advances we not only would be accomplishing little: we would be in no position to react quickly at any other place along the front.23

In the meantime the First Army’s attack against the Roer dams had gotten off as scheduled on December 13, but relatively few divisions were engaged. Early in the month the weather, which had been intermittently bad, took a turn for the worse. Fog and clouds practically prohibited aerial reconnaissance and snows began to appear in the uplands, together with increasing cold.24

The German Sixth Panzer Army, which had appeared on our front, was the strongest and most efficient mobile reserve remaining to the enemy within his whole country. When it arrived on our front it was originally stationed opposite the left of the Twelfth Army Group, apparently to operate against any crossing of the Roer. When the American attacks on that front had to be suspended early in December, we lost track of the Sixth Panzer Army and could not locate it by any means available. At that time some Intelligence reports indicated a growing anxiety about our weakness in the Ardennes, where we knew that the enemy was increasing his infantry formations. Previously he had, like ourselves, been using that portion of the front in which to rest tired divisions.25

This type of report, however, is always coming from one portion or another of a front. The commander who took counsel only of all the gloomy Intelligence estimates would never win a battle; he would forever be sitting, fearfully waiting for the predicted catastrophes. In this case I later learned that the man who predicted the coming of the attack estimated, during its crisis, that the enemy had six or seven divisions of fresh and unused reserves ready to hurl into the fight.

In any event the fighting during the autumn followed the pattern I had personally prescribed. We remained on the offensive and weakened ourselves where necessary to maintain those offensives. This plan gave the German opportunity to launch his attack against a weak portion of our lines. If giving him that chance is to be condemned by historians, their condemnation should be directed at me alone.