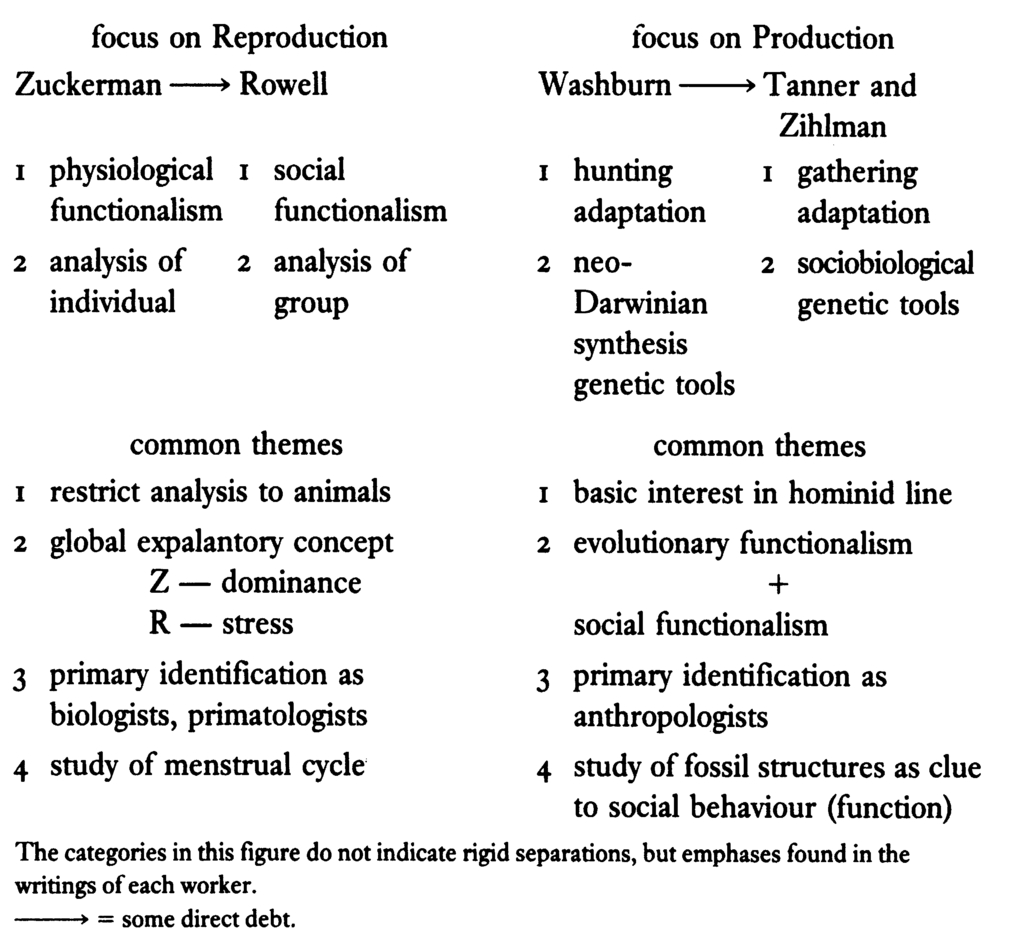

FIGURE 1: RELATIONS OF MAJOR FIGURES

People like to look at animals, even to learn from them about human beings and human society. People in the twentieth century have been no exception. We find the themes of modern America reflected in detail in the bodies and lives of animals. We polish an animal mirror to look for ourselves. The biological sciences' focus on monkeys and apes has sought to make visible both the form and the history of our personal and social bodies. Biology has been pre-eminently a science of visible form, the dissection of visible shape, and the acceptance and construction of visible order. The science of non-human primates, primatology, may be a source of insight or a source of illusion. The issue rests on our skill in the construction of mirrors.

Primatology has focused on two major themes in interpreting the significance of animals for understanding human life - sex and economics, reproduction and production. The crucial transitions from a natural to a political economy and from biological social groups to the order of human kinship categories and systems of exchange have been basic concerns. These are old questions with complex relations to technical and ideological dimensions of biosocial science. Our understandings of both reproduction and production have double-edged possibilities. On the one hand, we may reinforce our vision of the natural and cultural necessity of domination; on the other, we may learn to practise our sciences so as to show more clearly the now fragmentary possibilities of producing and reproducing our lives without overwhelming reliance on the theoretical categories and concrete practices of control and enmity.

Theories of animal and human society based on sex and reproduction have been powerful in legitimating beliefs in the natural necessity of aggression, competition, and hierarchy. In the 1920s, primate studies began to claim that all primates differ from other mammals in the nature of their reproductive physiology: primates possess the menstrual cycle. That physiology was asserted to be fraught with consequences, often expressed in the fantasy-inspiring 'fact' of constant female 'receptivity'. Perhaps, many have thought and some have hoped, the key to the extraordinary sociability of the primate order rests on a sexual foundation of society, in a family rooted in the glands and the genes. Natural kinship was then seen to be transformed by the specifically human, language-mediated categories that gave rational order to nature in the birth of culture. Through classifying by naming, by creating kinds, culture would then be the logical domination of a necessary but dangerous instinctual nature. Perhaps human beings found the key to control of sex, the source of and threat to all other kinds of order, in the categories of kinship. We learned that in naming our kind, we could control our kin. Only recently and tentatively have primatologists seriously challenged the indispensability of these sorts of explanations of nature and culture.

Biosocial theories focusing on production rest on a fundamental premise: humankind is self-made in the most literal sense. Our bodies are the product of the tool-using adaptation which predates the genus Homo. We actively determined our design through tools that mediate the human exchange with nature. This condition of our existence may be visualized in two contradictory ways. Gazing at the tools themselves, we may choose to forget that they only mediate our labour. From that perspective, we see our brains and our other products impelling us on a historical course of escalating technological domination; that is, we build an alienated relation to nature. We see our specific historical edifice as both inevitable human nature and technical necessity. This logic leads to the superiority of the machine and its products and ensures the obsolescence of the body and the legitimacy of human engineering. Or, we may focus on the labour process itself and reconstruct our sense of nature, origins, and the past so that the human future is in our hands. We may return from the tool to the body, in its personal and social forms. This chapter is about efforts to know the body in the biosocial conditions of production and reproduction. Our bodies, ourselves.

More particularly, this chapter is about the debate since approximately 1930 in primate studies and physical anthropology about human nature - in male bodies and female ones. The debate has been bounded by the rules of ordinary scientific discourse. This highly regulated space makes room for technical papers; grant applications; informal networks of students, teachers, and laboratories; official symposia to promote methods and interpretations; and finally, textbooks to socialize new scientists. The space considered in this chapter does not provide room for outsiders and amateurs. One of the peculiar characteristics of science is thought to be that by knowing past regularities and processes we can predict events and thereby control them. That is, with our sciences - historical, disciplined forms of theorizing about our experience - we both understand and construct our place in the world and develop strategies for shaping the future.

How can feminism, a political position about love and power, have anything to do with science as I have described it? Feminism, I suggest, can draw from a basic insight of critical theory. The starting point of critical theory - as we have learned it from Marx, the Frankfurt school, and others is that the social and economic means of human liberation are within our grasp. Nevertheless, we continue to live out relations of domination and scarcity. There is the possibility of overturning that order of things. The study of this contradiction may be applied to all our knowledge, including natural science. The critical tradition insists that we analyse relations of dominance in consciousness as well as material interests, that we see domination as a derivative of theory, not of nature. A feminist history of science, which must be a collective achievement, could examine that part of biosocial science in which our alleged evolutionary biology is traced and supposedly inevitable patterns of order based on domination are legitimated. The examination should play seriously with the rich ambiguity and metaphorical possibilities of both technical and ordinary words. Feminists reappropriate science in order to discover and to define what is 'natural' for ourselves.1 A human past and future would be placed in our hands. This avowedly interested approach to science promises to take seriously the rules of scientific discourse without worshipping the fetish of scientific objectivity.

My focus will be four sets of theories that emphasize the categories of reproduction and production in the tangled web of the reconstruction of human nature and evolution. The first, centring on reproduction, was the work of Sir Solly Zuckerman. Born in 1904 in South Africa, he studied anatomy at the University of Cape Town, then earned his MD and BS at University College Hospital, London. He combined in complex and illuminating ways research interests in human palaeontology and physical anthropology, reproductive physiology and the primate menstrual cycle, and broad zoological and taxonomic questions focused on primates. His social base included zoological gardens and research laboratories in British universities and medical schools; his training and career reflect intersections of the perspectives of anatomist, biochemist, anthropologist, clinician, administrator, and government science adviser.2 He has been the architect of an extremely influential theory that sexual physiology is the foundation of primate social order. He also offered a variation of the theory of the origin of human culture in the hunting adaption, which delineated crucial consequences for the division of labour by sex and the universal institution of the human family. In focusing on the sexual biology of monkeys, Zuckerman constructed a logic for setting the boundaries of human nature. In effect, Zuckerman claimed, the only universal for all the primates is the menstrual cycle. Therefore, only on that basis may we make valid comparisons of human and non-human ways of life.

A second set of theories stressing reproduction is that of Thelma Rowell, now at the University of California at Berkeley. She earned her doctorate in the early 1960s under Robert Hinde of Cambridge, the man who also supervised Jane Goodall's dissertation on chimpanzees. That period saw the beginning of a still continuing acceleration of publication based on long-term field observations of wild primates. Rowell's training was in zoology and ethology. Her first intention was to write her thesis on mammalian (hamster) communication, using the etiological approach worked out particularly by Niko Tinbergen at Oxford. Because Tinbergen then felt the methodology to be inappropriate to the non-stereotypical social communication of mammals, Rowell pursued her ideas at Cambridge under Hinde, a major synthesizer of American comparative psychology and Continental ethology. Rowell's research (1966a, 1966b, 1970), which has used both traditions, has been concerned with primate communication, the baboon menstrual cycle, comparison of the naturalistic behaviour of monkeys with their behaviour in captivity and in laboratory experimental situations, and mother-infant socialization systems. An outspoken critic of the pervasive dominance concept, she has made social role and stress her overriding theoretical concerns.

Yet both Zuckerman and Rowell, who are very different, adopt varieties of biological and sociological functionalism that set limits on permitted explanations of the body and body politic. The most important is the functionalist requirement of an ultimate explanation in terms of equilibrium, stability, balance. Functionalism has been developed on a foundation of organismic metaphors, in which diverse physiological parts or subsystems are co-ordinated into a harmonious, hierarchical whole. Conflict is subordinated to a teleology of common interests.3 Both Zuckerman's and Rowell's explanations also reflect the ideological concerns of their society in complex ways, which can instruct feminist efforts to deal with biological and social theories.

The third and fourth sets of theories are reconstructions of human evolution. Both claim to reveal the meaning of crucial adaptations, both focus on production. They see adaptation as a concept relating to the interpretation of functional complexes, of ways of life in which behaviour and structure mutually inform each other. If both Rowell and Zuckerman restrict themselves (almost) to talking about monkeys, Sherwood Washburn of the University of California at Berkeley, his former student Adrienne Zihlman, and her colleague at the University of California at Santa Cruz, Nancy Tanner, argue about the connection of physical and social anthropology. Telling scientific tales about human nature, they are unapologetic about the place of speculative reconstruction in the study of evolution. There can be no hiding behind mechanistic or purely structural explanations in evolutionary biology and anthropology. But since function is still pre-eminent, the resulting scientific approach may be called evolutionary functionalism.

The central figure in the third set of theories, Washburn, is most immediately associated with the modern man-the-hunter hypothesis. This maintains that the hunting adaptation has been the fundamental functional complex which set the rules for nearly all the history of the genus Homo until the very recent past. He has also generated the theory of tool use as the motor of evolution of the human body, including the brain and its power of language. His influential vision of the self-made species has earned him praise from such Marxist feminists as Eleanor Leacock (1972) and such Freudian feminists as Dorothy Dinnerstein (1977). He has also been an arch-villain of the piece because of the overwhelming concentration on males as practically the only active sort of human being. Washburn is, in my opinion, both more complicated and more important than either approach reveals. By developing functional anatomy as part of the synthetic theory of evolution and then extending the approach to the social behaviour of living primates, he has integrated sophisticated genetic theory and disciplined field and experimental methodology into the practice of evolutionary reconstruction.

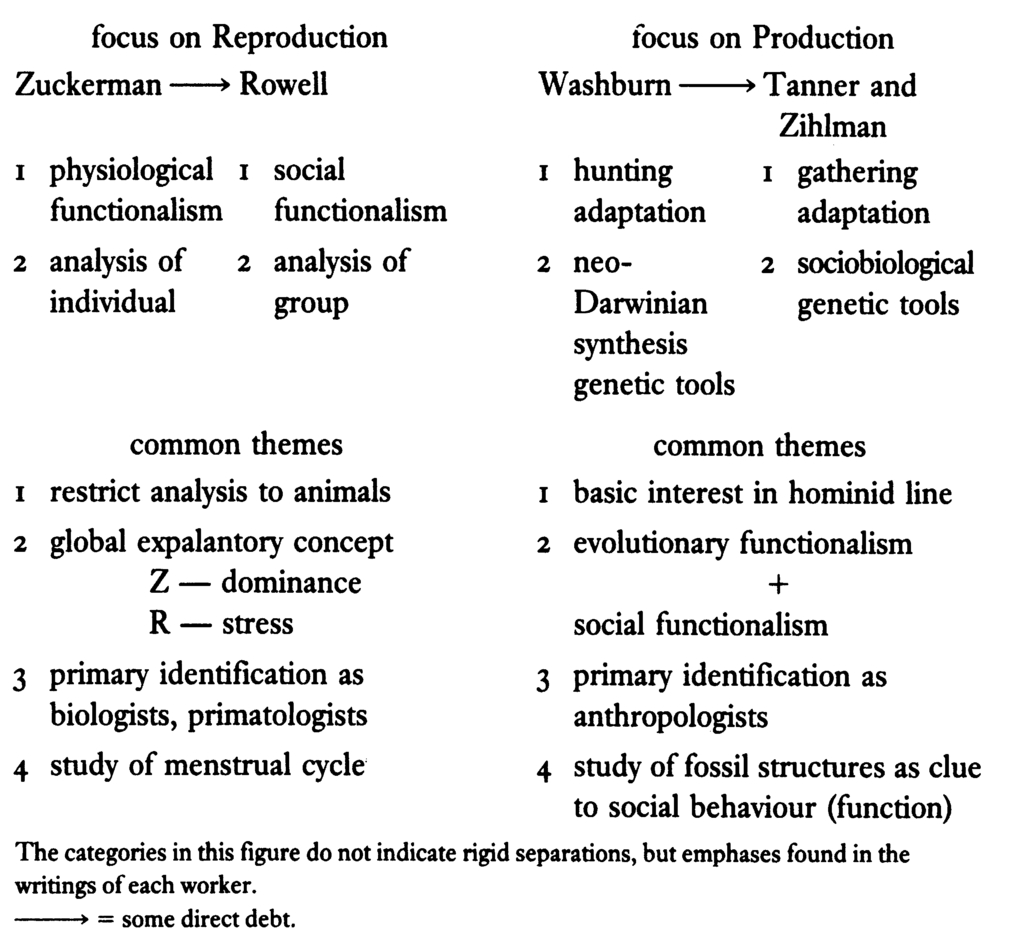

Authors of the fourth set of theories, Zihlman and Tanner, have produced an excellent critique of Washburn's scientific sexism with the use of his own tools. They could not have thought as they do without the functional physical anthropology Washburn has advanced. Tanner and Zihlman have also added a new twist to feminist, scientific evolutionary reconstruction: the use of sociobiological concepts. The pleasure and irony of their approach is that the ideas of some of the most explicitly sexist theories have been enlisted to tell another story. Yet at this level, the feminist debate is still about the nature and existence of human universals. Theories of origins quickly become theories of essences and limits (see Figure 1).

The 1930s was a decade of exciting advance in the study of sexual endocrinology. Early in the decade Solly Zuckerman produced a powerful theory of the physiological basis of mammalian society in general and primate society in particular. He repeatedly asserted that he intended only to adopt a zoologist's perspective on animal sociology and to avoid extrapolation to human, cultural, language-mediated behaviour. Yet his work informed investigations into the origin of human organization and the use of primates in studies of it. He gave the concept of dominance an up-to-date scientific legitimation, for example, connecting it to the new endocrinology. Dominance was closely linked, in his theory, to male competition for control of resources (females). Females then emerged as natural raw material for the

FIGURE 1: RELATIONS OF MAJOR FIGURES

imposition of male order through the consequences of reproductive physiology. The human innovation was the practice of control of the natural physiological economy. In brief, domination changed levels with culture.

Zuckerman's starting point for considering the causes of primate sociability was twofold: (1) debate in the anthropological community - represented by Malinowski's Sex and Repression in Savage Society and Freud's Totem and Taboo and Civilization and Its Discontents - on the cultural domination of instinct in the formation of the human level of organization; and (2) a new biological discipline, relating hormones and behaviour, rooted in neural and reproductive physiology and comparative and behaviourist psychology. Zuckerman adopted a firm physiological and medical orientation in both areas. He criticized all existing theories of animal organization for their anthropomorphic and teleological overtones. For the older evolutionary meaning of functional adaptation, Zuckerman substituted a physiological approach, which rested on studies of particular mechanisms in anatomical and biochemical terms. Function meant mechanism. Behaviour and society were to be related to mechanistic physiology, and taxonomy was to be reformed on that basis as well. The taxonomic project was undertaken in the book, Functional Affinities of Man, Monkeys, and Apes (1933). Here, Zuckerman constructed his 'hunting hypothesis' to account for the transition from nature to culture.

But first we must look at his general theory of non-human primate society, found in The Social Life of Monkeys and Apes (1932). Zuckerman imposed an important limit on primatology. He did not recognize a ladder of perfection of living primates representing stages of mental function and corresponding degrees of social co-operation (which always meant hierarchical organization) through which human beings must have passed. Thus, 'Only the behavior common to all apes and monkeys can be regarded as representing a social level through which man once passed in the prehuman stages of his development' (1932, p. 26). Only one thing met this requirement: 'When all questions of its applications to human behavior are laid aside, and when teleological speculation is disregarded, the chief subject matter of a scientific mammalian sociology is seen to be ecology, reproductive physiology, and those influences which can be classed together as due to the variations of the individual' (1932, p. 28). That nod to ecology is the last we hear of it until a precipitating cause was later required to fire the cultural answer (hunting) to primate sexuality. Individual variation explained details, 'But social behavior - the interrelation of individuals within a group - is determined primarily by the mechanisms of reproductive physiology' (p. 29).

Zuckerman had already told the reader that his excursion into mammalian sociology had begun in response to the urgings of anthropologists; he aimed to replace anecdotal accounts of animal societies with hard physiology. He simply assumed that the important bone of contention was the nature and origin of the human family, itself the origin of society. At this point, Zuckerman turned to the writings of the American mammologist, G. S. Miller, who had criticized Malinowski's contention that the human family was unique, that kinship represented the crucial human-animal break. Malinowski regarded the human physiology on which the institution of kinship (i.e., fatherhood) was imposed as unique. In contrast, Miller and Zuckerman agreed that one found all the biological essentials of the human family (namely, constant female receptivity) in mammalian reproductive association. Zuckerman simply developed that viewpoint into an analysis of consequent social forms among primates. Freud's story of the origin of civilization in repression was prefigured on the prehuman level. Zuckerman's story was based on the comparative physiological anatomy of the different primate groups informed by his recent discovery of the baboon menstrual cycle and on the behaviour of a colony of Hamadryas baboons on Monkey Hill in the London Zoo since 1925. The zoo behavioural observations were supplemented by nine days of field study of a different species (the chacma baboon) in South Africa during an excursion to collect anatomical material for the study of reproduction.

The logic of his story, though exquisitely simple, influenced a whole domain of advanced research and provided the logical ground for the new science of hormones and behaviour to encompass the study of social order. Animals, except when they come together to reproduce, are solitary because the basic model of life is competition for scarce resources. Reproductive association is fraught with danger because here competitive success requires the co-operation of other animals. Males fight to obtain the maximum number of reproductive opportunities. These elements Zuckerman retained from Darwin. They did not appear teleological to him in the same way as discussions of animal altruism and co-operation. Males dominate females to preclude another source of competitive insubordination. After the bare essentials of reproduction are accounted for, animals separate to avoid further inevitable injuries from sexual battles. Sexual periodicity (seasonality) evolved to protect the animal atoms from each other during the rest of the year. Mother-young groups hardly constitute society. In any case, these groups are general to mammals and cannot explain primate societies. Different degrees of long-term heterosexual association were rigorously related to requirements of reproduction in the particular ecological environments available to the animals. Males compete to accumulate the means of (re)production, through which alone they can increase their genetic capital in evolution. Females are the means of evolutionary production and the source of surplus value. As dominance became the universal medium of exchange among males and the measure of value, the political and natural economy of Hobbes's Leviathan has found its twentieth-century biological expression. The economic order is exclusively physiological in all but human beings, where cultural ownership of females and property is also to be found.

To Zuckerman, the main event in social evolution had been the elimination of extreme seasonality and the introduction of year-long association based on the continuous sexual 'receptivity' of females. First the oestrus and then the menstrual cycle introduced regular repeating bouts of sexual intercourse. Monthly cycles replaced seasonal ones, and a social revolution ensued. Continuous association required strong control mechanisms if the animals were to survive it. So developed the 'harem', exemplified by the London Hamadryas which Zuckerman observed personally during 1929-30 and for which he had records dating to the establishment of the colony in 1925. Especially since the London Hamadryas did not survive on Monkey Hill - nearly all were killed in brutal fights and only one infant was reared successfully - it was important for Zuckerman to establish that captive baboons in extreme conditions of sexual imbalance and crowding still revealed the essential structure of primate society in nature. The traditional physiological argument was used: extreme circumstances are the best windows to the normal because they highlight basic mechanisms which would otherwise be obscured. Hierarchy and deadly competition were crucial regulators of primate society, not creations of human captors. It was also important for him to convince his readers that variations in social form among primates, none of whom had been studied in other than a casual way in the wild, were only details imposed upon the fundamental physiologically determined family. Within the pattern of dominance, such behaviour as female 'prostitution' (which Zuckerman and Miller defined as presenting for non-sexual reasons) was explained as the beginning of the trading of sexual favours for otherwise competitively unobtainable goods. Grooming, feeding order, vocal and gestural expression, allotment of social space, and many other aspects of social behaviour were all derived from the physiologically determined harem organization of primates. Zuckerman was unequivocal:

The argument outlined above goes far toward explaining the broad basis of subhuman primate society. The main factor that determines social grouping in subhuman primates is sexual attraction ... The limit to the number of females held by any single male is determined by his degree of dominance, which will again depend not only on his own potency, but also upon his relationship with his fellow males. (Zuckerman, 1932, p. 31)

Of course, human beings share with other primates 'a smooth and uninterrupted sexual and reproductive life' (p. 51); yet human beings and their families exist in the realm of culture, buffered, if not exempt, from the physiologist's gonadectomies and injections. How did the physiologist re-enter the kingdom of culture with his medical tools for producing family health and behavioural adjustment within social hierarchy defined as co-operation? Through hunting, through the taste for meat. Returning to Functional Affinities, we meet Zuckerman in his guise as physical anthropologist who unites the physiological to the ecological in order to generate a large-brained hunting animal who needs more complex forms of male co-operation and female fidelity in order to feed the family. The reproductive unit remains on the throne as the fundamental core of social association in the cultural form of kinship, the basic object of the social science of cultural anthropology. Again, Zuckerman's logic is elegantly simple. Some unknown ecological changes produced selection pressure for prehumans to exploit new sources of food, to rework the age-old unspecialized feeding patterns, and to introduce sexual division of labour as a necessary consequence of the requirements of large-scale meat-eating. Food-sharing necessitated the human form of the family, which for Zuckerman meant selection pressure for 'overt monogamy' and conceptual recognition of significant social relations (ownership of women) even when no one was around to enforce them. The passivity of females in such major transformations was an unexamined assumption. So developed marriage and the hunting band of males, with all the startling consequences for the brain and its products of speech and culture.

Zuckerman hinted at the later form of the hunting hypothesis that emphasized the tool-using adaptation in the origin of the self-made species. But more important was the fact that the all-male band - the human form of co-operation signalling the divorce of culture from nature - became a scientific, even a physiological, object in Zuckerman's hands. The valuable female continued to pose the threat of disorder through sexuality. Co-operation came to mean conscious male regulation of previously natural hierarchy and competition, which in turn had been the fruits of permanent female sexuality. These themes were not new with Zuckerman, but the way he integrated them into modern physiological disciplines was. Further, his biological ideology did not violate, but actually reinforced, the important doctrine of the autonomy of biological and social science, of animal and human order. Zuckerman left full room for functionalist social anthropology. He only reformed Malinowski's physiology.

Zuckerman's importance in the development of primate behaviour studies themselves has not been his scant empirical observations, but his provision of a theory that met the needs of rapidly advancing new disciplines. At the same time, he rescientized conventional prejudices with the liberal ideology that claimed that culture was autonomous from previous forms of biological determinism. That same liberal ideology legitimated a logic of scientific control over 'nature', now rationalized as a material given reduced either to pre-rational danger or ordered resource. The alienating core of this is not obscure. Zuckerman set questions for workers to follow that even in their asking reinforced scientific beliefs about natural male competition and dangerous female sexuality. His tie of sexuality to dominance in ways acceptable to the physiological and behavioural sciences of the 1930s helped establish the status of dominance as a trait or fact rather than a concept. Primatologists have continued to ask about the selective advantage of dominance behaviour and have tended to assume, rather than test, a correlation of breeding advantage with an entity called dominance. Not until 1965, with a paper by two of Sherwood Washburn's students, was his theory of the origin of primate society in year-round female sexuality convincingly laid to rest.4 Zuckerman's mode of blending covert Freudianism, biochemical mechanisms, and studies of social behaviour has had a long and influential life.

At first glance, the only comparisons of Thelma Rowell with Zuckerman must be in contrast. Though she praised Zuckerman for his ground-breaking work on the baboon menstrual cycle and refrained from very severe criticism of him in her historical paper on the dominance concept, her whole work seems to have been in opposition to his ideas and his methods. She does not claim scientific purity for a language bathed in multiple waves of meaning in the common tongue as well as in scientific tradition. Her arguments have been zoological and explicitly sociological rather than an extrapolation from reproductive physiology. She is known for her care in dividing cage space for captive monkeys to permit more naturalistic behaviour, and for excellent field studies, rather than for physiological arguments about provoked extreme behaviour as the window to the normal. Rather than emphasizing primate universals, Rowell's papers are permeated by particularism, by counsels to notice complexity, by insistence on variability in a manner reminiscent of early proponents of the culture concept and cultural particularism. Moreover, Rowell is working in very different scientific and ideological circumstances. She benefits from and contributes to the now extensive literature based on direct field studies of primates, studies which themselves referred back to Zuckerman but went beyond that to which he had access. This body of literature has tended to reject Zuckerman's doctrines on sex but to retain focus on dominance. Finally, Rowell writes to an audience sensitized to the feminist implications of biosocial theory. It is not an accident that she emphasizes female behaviour and active social roles and finds dominance to be, at best, a convenient expression for predicting the frequency of some learned behaviours.

But it would be a dangerous mistake to see Rowell's work as simply exemplifying normal scientific progress in rooting out unnecessary prejudice while accumulating better data. Nor does her work simply substitute more satisfying (to me) female prejudices for Zuckerman's infuriating male consciousness. In fact, Rowell and Zuckerman are like each other in a crucial way, which I believe indicates part of the nature of the ideological function of impeccable work in perfectly controlled laboratory science. In 'stress', Rowell does have a global category of explanation corresponding to Zuckerman's sexual physiology. Like sex or dominance, stress is a category that incorporates general social belief into the extracts in the biochemist's test-tube. Stress may be studied on the level of adrenal function, on the level of mental illness, or on the level of'explanation' of life in modern capitalism. If dominance was the crucial concept in the 1930s, in a context of extraordinary scientific and popular concern for the foundation of social co-operation and competition in a time of world crisis, then stress has been the favourite concept, in the guise of a thing, in more recent times of serious threat to privileged social order. Dominance is not dead, but stress is really more useful in social theory. It has a further referent, namely, to the concept of a social system and to structural functionalism as the principal mode of sociological explanation. The physical metaphors of systems theories - like tolerance, stress, balance, and equilibrium - lead us to many levels of meaning. One which we must note is that of the idea of 'obsolescence' of certain biological systems and the medical function of relieving stressed, perhaps obsolescent, behaviour patterns. A second level of meaning implicit in systems functionalism is the imperative of'reproduction' of the system as a social whole and as a breeding population. Behaviour can be explained, then, ultimately in terms of system maintenance or pathological failure to achieve such stability.

In 1974, Rowell summarized the arguments against use of the dominance concept to understand social structure. She gave two major lines of approach: (1) presenting all putative dominance behaviours as learned responses easily accounted for by current theories in animal psychology; and (2) removing the basis for considering dominance as a trait or adaptive complex subject to selection pressures. That is, so-called dominance behaviours do not seem to relate to reproductive success. In addition to amusing points about the slippery nature of concepts like 'latent dominance', which enter arguments to fill gaps in observation, Rowell asserts that conditions of observation introduce the determinants in which one should expect social animals to learn responses called dominance. Hierarchy for Rowell is primarily an artefact of methods of observation. Reinforcing this position is the discovery that different measures of dominance do not correlate highly with each other, and hierarchies worked out by different measures do not reveal the same social structure. Thus it is hard to see what observed behaviours related to dominance have to do with evolution, which requires a genetic basis for selection. In Rowell's words, 'the function of dominance becomes a non-question' (1974, p. 151; italics altered).

But function does remain the essential question, the grail that unifies the actors in this chapter. For Rowell, function must be seen in terms of the concept of social system. Communication analysis, studies of mother-young interactions, role change in relation to age and sex class, social subsystems based on matrilines (kinship), territory and hierarchy as spatial order, and variation of social structure in response to environmental variables: these become the areas of interest, the analytical objects that bear on the structural-functional explanation of system in terms of function. Rowell's theoretical stance is most plain in her very useful, linguistically sophisticated book, Social Behaviour of Monkeys (1972). The problem of the social system is the problem of multiple-variable analysis in fluid structures in dynamic equilibrium through time and space. The debt of animal sociology to human sociology and anthropology from Bronislaw Malinowski, L.J. Henderson, and Talcott Parsons has hardly begun to be noticed, much less critically examined.

How does stress relate to the social system? Ironically, through the concept of subordination hierarchies. Animals would be compared to each other on a scale of susceptibility to stress. Very sensitive animals would be easily roused to fear, flight, or cringing postures. Such sensitivity would reasonably be associated with high levels of adrenal-stimulating hormones. So the capacity to produce ACTH in 'stressful' situations would be reasonably postulated to have a genetic foundation. These are testable propositions, at least in principle. Calm animals might be called 'dominant' by observers simply because they move freely in social space and take freely from available resources, while their nervous comrades cringe or move away. Rowell would see the poor huddling beast as the stimulus or cause of the resulting 'hierarchy'. Such a social scheme should be called a subordination order. A variety of response thresholds to stressful situations would be adaptive in the social group in nature. Both nervous and calm animals would have a role in efficiently monitoring the environment for danger or for maintaining intragroup peace. The genetic diversity in the population underlying the differences in response stress would be kept in evolution. One must note how functionalist notions of social role for overall system balance, genetic concepts for biochemical and hormonal function, and psychological approaches to dominance-subordination all converge in the central idea of stress.

Stress as a global, multi-layered concept embedded in functionalist explanation provides the critical tie between Thelma Rowell and Sherwood Washburn. The tie is represented by David Hamburg, later president of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences, in the 1960s chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at the Stanford School of Medicine, and collaborator with Sherwood Washburn in building primate studies around modern medical and evolutionary questions. In Hamburg's and Washburn's work, the darker side of functionalist explanation is starkly revealed; the metaphoric structure surrounding stress ceases to be more congenial than dominance. Hamburg has been a principal figure in evolutionary theories of emotional adaptive configuration, which lead to the notion of our obsolescent biology. Medical management of emotions maladaptive in 'modern society' seems justified to relieve pathological stress and maintain the social system. 'Modern society' itself seems given by some sort of technological imperative laid over our limiting biological heritage. Primate studies are motivated by, and in turn legitimate, the management needs of a stressed society. The animals model our limitations (adaptive breakdowns) and our innovations (tool use).

Social functionalism and evolutionary functionalism come together in the study of selection for behaviours and emotional patterns that maintain societies as successful breeding populations over time. The imperative is reproduction - of the social system and of the organisms who are its member-role actors. In general, animals have to like to do what they must do to survive in their evolutionary history. Evolutionary theory here joins a sociology of systems and a psychology of personality and emotion in modern versions of a pleasure calculus connected to the organic, motivational base of learning theory. Rowell summarizes:

A zoologist, however, must always return to the question of selective advantages ... It is so very obvious that monkeys enjoy being together that we take it for granted. But pleasure like every other phenomenon of life is subject to, and the result of, evolutionary pressure - we enjoy a tiling because our ancestors survived better and left more viable offspring than their relations who did not enjoy (and so seek) comparable stimuli ... This is speculation; but it is by research which examines the function of social systems of monkeys and other animals that we shall be able to understand fully their mechanisms. (1972, pp. 174, 180)

Washburn and Hamburg have shared the same analysis, but have applied it to another concept, again often perceived as a thing, in the vocabulary of meaning-laden scientific words: aggression, especially male aggression. Through this concept we must make a transition from explanations based on theories of reproduction to those based on production in human evolution and primate behaviour studies. Clearly, reproduction and production are complements, not opposites. But we must see how Washburn reached a 'man-the-hunter' theory from consideration of the economic functions of the species, while Zuckerman traced primate order through reproductive physiology, and Rowell led us to understand the junction of sociological and evolutionary notions of reproducing systems.

Washburn and Hamburg (1968) developed themes initiated in their collaboration in 1957, when Washburn spent a year as a fellow at the Stanford Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, and furthered in 1962-63 when Washburn and Hamburg organized at the centre a full year of conferences and collaboration among the new, exciting, world-wide community of primatologists. In 'Aggressive behavior in Old World monkeys and apes', the two collaborators introduced their work as part of the study of the forces that produced humankind. They wished to pay attention to unique human biology and unique conditions of human evolution. They saw aggression as a fundamental adaptation or functional complex common to the entire primate order, including human beings. 'Order within most primate groups is maintained by a hierarchy, which depends ultimately primarily on the power of males ... Aggressive individuals are essential actors in the social system and competition between groups is necessary for species dispersal and control of local populations' (1968, p. 282). The biology of aggression has been extensively studied and seems, they argue, to rest on similar hormonal and neural mechanisms, modified in primates, and especially in humans, by new brain complexes and extensive learning. In non-human primates, aggression is constantly rewarded, and, the authors maintain, aggressive individuals (males) leave more offspring. So they argue for selection of a system of co-adapted genes involving complex feedback among motor anatomy, gestural anatomy, hormones, brain elements, and behaviour. Presumably, all parts of the aggressive complex evolve. The functions requiring aggression did not abate for humankind, Hamburg and Washburn believe. Protection, policing, and finally hunting all required a continued selection for male organisms who easily learned and enjoyed regulated fighting, torturing, and killing:

Throughout most of human history societies have depended on young adult males to hunt, to fight, and to maintain the social order with violence. Even when the individual was cooperating, his social role could be executed only by extremely aggressive action that was learned in play, was socially approved, and was presumably gratifying. (1968, p. 291)

But with the advance of civilization, this biology has become a problem. It is now often maladaptive because of our accelerating technological progress. Our bodies, with the old genetic transmission, have not kept pace with the new language-produced cultural transmission of technology. So now, when social control breaks down, we must expect to see pathological destruction. Hamburg and Washburn's examples here are Nazi Germany, the Congo, Algeria, and Vietnam! The lesson is that we must face our nature in order to control it. 'There is a fundamental difficulty in the fact that contemporary human groups are led by primates whose evolutionary history dictates, through both biological and social transmission, a strong dominance orientation' (1968, p. 295). This logic has been developed to posit a need for scientifically informed, rational controls to replace pre-scientific customs: 'But an aggressive species living by prescientific customs in a scientifically advanced world will pay a tremendous price in interindividual conflict and international war' (p. 296). The lesson here, the liberal scientist argues, is not to favour a particular social order - those are political and value questions - but to establish the preconditions for all advanced society, namely, scientific management of now inefficient, maladaptive, obsolescent biology. We are only one product, and one subject to considerable breakdown. On the personal level, psychiatric therapy is a species of repair work; on the social level, scientific policy dictates we use our skill to update our biology through social control. Our system of production has transcended us; we need quality control.

But before despairing that society is doomed to hierarchies and dominance relations regulated by scientific management, let us ask more closely what convinces Washburn and Hamburg that we, or at least males, have a woefully aggressive nature. After all, human males do not have the so-called fighting anatomy of many primate males - the dagger-like canines, associated threat gestures so appropriate for ethological analysis, great difference in male and female body size, or extra structures such as a mane to enhance one's threatening aspect. Nor do we have appeasement gestures to placate aggressors. Why argue that we do have an aggressive, authority-requiring brain? The line leading to the genus Homo, Washburn judges, was bipedal and tool-using very early. Selection pressures favoured increased tool use, which in turn made possible the hunting way of life, evolution of a big brain, and language. Human males no longer fought with teeth and gestures but with words and handmade weapons. We lack big canines because we make knives and hurl insults. The selection pressures requiring aggression did not abate, but the structural basis for the function evolved in harmony with the whole adaptational complex of a new way of life. This argument itself relates to Washburn's basic reformulation of physical anthropology, beginning in the 1940s, as part of the synthetic theory of evolution, and to his successful efforts to promote primate behaviour studies in the study of human evolution.

Washburn earned his PhD in physical anthropology at Harvard in 1940. His training was in traditional anthropometric methods and primate anatomy, and he taught medical anatomy at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons until 1947, when he moved to the University of Chicago. He had accompanied the 1937 Asia Primate Expedition, from which C.R. Carpenter produced the first monograph on gibbon behaviour and social system. But Washburn felt Carpenter then had little sense of the exciting possibilities of the concept of social system. His own task on the expedition was anatomical collecting, that is, shooting specimens. By the mid-1940s Washburn was practising physical anthropology as an experimental science; by 1950 he was developing a powerful programme for reinterpreting the basic concepts and methods of his field in harmony with the new population genetics, systematics, and palaeontology of Dobzhansky, Mayr, and Simpson. By 1958, he had a Ford Foundation grant to study the evolution of human behaviour in a complex manner, including provision for field studies of baboons in East Africa. A year later, now at Berkeley, he developed funding for one of the first experimental primate field stations in the United States. From the beginning of his career, he lectured, wrote popular texts, made pedagogical films, reformed curricula on all educational levels, and promoted successful careers of now well-known figures in evolution and primatology.

This is not the place to explore the origins of Washburn's ideas, nor his organization of a very large research and education programme, but only to note essential features in relation to the hunting thesis and primate behaviour.5 The purpose is to begin to recognize how Washburn's career as a careful, experimental scientist has been part of the scientific and social controversies on human nature as the foundation for the human future. We must understand how Washburn could simultaneously be the co-author of the article on evolution of aggression, an opponent of sociobiology, alternately a hero and villain for Robert Ardrey, a favourite of some Marxist feminists, and the teacher of both sociobiological feminist Adrienne Zihlman and of sociobiological sexist Irven DeVore. He is rightly all these things and unusually consistent and unified in his methods, theories, and practices. Perhaps the key to Washburn is that he has produced a fundamental theory with tremendous implications for the practice of many sciences and for the rules of speculative evolutionary reconstruction. In Kuhnian terms, Washburn seems to have something basic to do with scientific paradigms. In Marxist terms, he has to do with alienated theorizing of the established disorder.

Washburn's fundamental innovation in physical anthropology was evident in the publication of his widely reprinted papers, 'The new physical anthropology' (1951a) and 'The analysis of primate evolution with particular reference to man' (1951b). He applied the new population genetics to the study of primate evolution. For Washburn population genetics meant that the process of evolution was the crucial problem, not the fossil results. Therefore, selection and adaptation were his central concepts. Adaptive traits could only be interpreted by understanding conditions or forces capable of producing the traits. The first problem that confronted the physical anthropologist was how to identify a 'trait'. Washburn practised a new kind of theoretical and practical dissection of the body into 'functional complexes', whose meaning had to be sought in their action during life. For example, instead of measuring the nose, he analysed the forces in the central region of the face from chewing and growth. That task required model experimental systems of living animals. Instead of setting up scales of evolution based on brain enlargement, he analysed regions of the body involved in adaptive transformations related to locomotion, eating, and similar functions. In sum, 'The anatomy of life, of integrated functions, does not know the artificial boundaries which still govern the dissection of a corpse' (1951a, p. 303).

Washburn was part of a larger revolution in physical anthropology accompanied by the discovery of new fossils, dating techniques, experimental possibilities, and more recently, molecular taxonomy. One of the revolution's central objects was the small-brained South African human-ape, Australopithecus. 'The discovery of the South African man-like apes, or small brained men, has made it possible to outline the basic adaptation which is the foundation of the human radiation' (1951b, p. 70). The origin of the human radiation was like any other mammalian group's, though its consequences were decidedly novel. 'But the use of tools brings in a set of factors which progressively modifies the evolutionary picture. It is particularly the task of the anthropologist to assess the way the development of culture affected physical evolution' {1951b, p. 71). Evolutionary and social functionalism again come together; both, for Washburn, are analyses of the meaning of living systems, of action, of ways of life. From the 1950s Washburn maintained that functional anatomy and the synthetic theory of evolution laid to rest for ever the old conflicts of physical and social anthropology.

In 1958, Washburn and his former student, Virginia Avis, contributed a paper to a symposium on behaviour and evolution, which had been organized, beginning in 1953, to effect a synthesis of comparative psychology and the synthetic theory. Washburn's emphasis on the importance of behaviour made his interest in the psychological consequences of evolutionary adaptation natural. In that paper, 'The evolution of human behavior', Washburn and Avis (1958) developed the consequences of the hunting adaptation, including enlarged curiosity and mobility, pleasure in the hunt and kill, and new ideas about our relation to other animals. Perhaps most important, 'Hunting not only necessitated new activities and new kinds of cooperation but changed the role of the adult male in the group ... The very same actions which caused man to be feared by other animals led to more cooperation, food sharing, and economic interdependence within the group' (pp. 433-4). The human way of life had begun.

From seeing behaviour first as motor activity and then as psychological orientations, it was a short, logical step to looking at behaviour as social system. Beginning in 1955, almost casually, Washburn investigated not only actions of individual organisms but of social systems. The baboon studies of Washburn and Irven DeVore, with all their emphasis on male roles in protection and policing as models of pre-adaptations to a human social system, were appropriate outgrowths of evolutionary functional anatomy. Differences between human and monkey society were always highlighted; Washburn never engaged in chain-of-being reconstructions. He looked at animal social systems the same way as he looked at forces determining growth in kitten skulls - as model systems for particular problems in interpreting skull formation in fossils. His was an experimental, comparative biological science based on function. But the baboon model system drove home a lesson: troop structure came from dominance hierarchies of males. Hunting transformed such structures but only to produce the special roles of the co-operating male band. The reproductive function of females, and the social continuity of matrilines, remained a conservative pattern reinforced by bigger-headed, more dependent infants.

The classic paper which brings together the anatomical, psychological, and social consequences of hunting in setting the rules for culture based on human nature is 'The evolution of hunting', by Washburn and C. S. Lancaster (1968). This paper has earned Washburn his poor reputation in socialist and feminist circles. Its appearance in a symposium emphasizing the hunting nature of man in the midst of years of challenge to sexual, economic, and political power is part of the social situation of contemporary evolutionary reconstruction, Washburn is not an ideologue; he is a scientist and educator. That is the point. Interpreting human nature is a central scientific question for evolutionary functionalism. The past sets the rules for possible futures in the 'limited' sense of showing us a biology created in conditions supposedly favouring aggressive male roles, female dependence, and stable social systems appropriately analysed with functional concepts. Telling stories of the human past is a rule-governed activity. Washburn's science changed the rules of the game to require argument from the conditions of production.

In 'Women in evolution. Part I: innovation and selection in human origins', Nancy Tanner and Adrienne Zihlman (1976)6 play by the new rules but tell of a different human nature, of different universals. They focus less on tools as such and more on the labour process, that is, on a new productive adaptation - gathering. They immediately place themselves within the recent population genetic developments of sociobiology. Their study explores a natural economy in terms of investment strategies for the increase of genetic capital. Yet Tanner and Zihlman deliberately appropriate sociobiology for feminist ends. They no more make themselves ideologues than Washburn has, but their practice of science is controversial both for internal reasons of debated evidence and argument, and for political reasons. They do not, at any point, leave the traditional social space of science. They can stay there, in part, because sociobiology is not necessarily sexist in the sense that Irven DeVore or Robert Trivers (1972) have made it, any more than the concept of stress necessarily leads to Hamburg's particular ideas on aggression and human obsolescence. Further, it is not easy to imagine what evolutionary theory would be like in any language other than classical capitalist political economy.7 No simple translation into other metaphors is possible or necessarily desirable. Tanner and Zihlman bring us face to face with fundamental questions that have barely been phrased, much less answered. How should we theorize our experience of the past and of 'nature' in new ways to build adequate concepts for scientific practice and social transformation? This question stands in a complicated relation with the internal craft rules for working within the natural sciences.

Tanner and Zihlman begin by announcing the goal of understanding human nature in terms of processes 'which shaped our physical, emotional, and cognitive characteristics' (1976, p. 585). They note the obvious fact that the hunting thesis has largely ignored the behaviour and social activity of one of the two sexes, and is therefore deficient by ordinary criteria of evolutionary functionalism. Behaviour does not fossilize for either sex, so the problem is one of rational reconstruction, of choosing hypotheses.

Specifically, we hypothesize the development of gathering [both plant and animal material] as a dietary specialization of savanna living, promoted by natural selection of appropriate tool using and bipedal behavior. We suggest how this interrelates with the roles of maternal socialization in kin selection and of female choice in sexual selection. We emphasize the connections among savanna living, technology, diet, social organization, and selective processes to account for the transition from a primate ancestor to the emergent human species. (Tanner and Zihlman, 1976, p. 586)

This paper is clearly a normal outgrowth for Zihlman of her 1966 presentation on bipedal behaviour, in the context of hunting, to a Washburn-organized symposium of the American Anthropological Association. Titled 'Design for Man', the session included Hamburg on emotions as adaptational complexes and the problem of maladaptive, obsolete patterns.

Like Washburn, Tanner and Zihlman argue from animal model systems and from the most recent genetic theory applied to populations. They see chimpanzees as the most closely similar of all living animals to the stem population that probably gave rise to apes and hominids. So chimpanzees make better mirrors, or models, than baboons do for glimpses of the evolution of the human way of life. The authors add to the traditional genetic parameters of the synthetic theory (drift, migration, and so on), the sociobiological genetic concepts of inclusive fitness, kin selection, sexual selection, and parental investment. Understanding changes in gene frequencies of populations from selection pressures operating on individuals remains the goal. They note lots of tool use by chimpanzees, with a sex difference in the behaviour. Females make and use tools more often, although the males seem to hunt more readily. Rigid dominance hierarchies do not occur, although the concepts of high ranks and influence seem useful. The social structure is flexible, but not random. Social continuity seems to flow through continuing associations of females, their young, and associates.

The transitional population to hominids is imagined to have moved into the savannah, a new adaptive zone. 'A new way of life is initiated by a change in behavior; the anatomical changes follow' (Tanner and Zihlman, 1976, p. 586). The new behaviour was greatly enlarged dietary choice accompanied by tool use. Gathering was the early critical invention of hominids. Food-sharing with ordinary social groups of females and offspring (including male sharing with these groups) resulted. Digging sticks, containers for food, and above all, carrying devices for babies were extremely likely early technological innovations related to the new diet and sharing habits. Knowledge of a wide range of plants and animals, as well as their seasons and habits, became important. Selection pressure for symbolic communication increased. The predation dangers of the savannah were probably dealt with by cunning not fighting, so hominids reduced the need for baboon-like dominance and male fighting anatomy. The flexible chimp social structure probably became even more opportunistic, allowing better understanding of the basis for human cultural diversity. Like Rowell, Tanner and Zihlman take every opportunity to emphasize human possibility and variety. Gathering of plants and animals was unlikely to maintain much selection pressure for an aggressive biology. Cognitive processes, on the other hand, were greatly elaborated in the new productive mode.

At this point, Tanner and Zihlman make use of mother-centred units to introduce kin and sexual selection and parental investment. New selection pressures put a premium on great sociability and co-operation. Babies were harder to raise, and bisexual co-operation would be useful. Males learned the friendly interaction patterns, even with strangers, which became crucial to the human way of life based on linguistic communities, small bands, and frequent outbreeding. But maintenance of a fighting anatomy including big canines and stereotyped threat gestures would be incompatible with the new functional behaviours. Females would mate more readily with friendly, non-threatening males. Female sexual choice has been shown to be general in mammalian groups, and the hominid stem was not likely to have been an exception. Two things leap at the reader who has followed Zuckerman's and Washburn's hunting arguments. First, female receptivity has been renamed female choice, with large genetic consequences. Second, the anatomy of the reduced canines is reinterpreted when different behaviour and different functions are postulated.

Tanner and Zihlman believe anthropology as a whole is better served by their different reconstruction, based on similar evidence.

Observers usually begin from their own perspective, and so inadvertently the question usually has been: how did the capacity and propensity for adult Western male behaviors evolve? This viewpoint offers scant preparation for comprehending the wide range of variability in women's roles in non-Western societies or for analyzing the changes in the roles of men and women which are currently occurring in the West. (Tanner and Zihlman, 1976, p. 608)

In other words, evolutionary reconstructions condition understanding of contemporary events and future possibilities. Tanner and Zihlman, in their interpretation of the tool-using adaptation, avoid telling a tale of obsolescence of the human body caught in a hunting past. The open future rests on a new past.

Focusing on the categories of reproduction and production, I have traced four major positions on human history and human nature. All were argued strictly within the boundaries of modern physiology, genetics, and social theory. All four hinged on the concept of function and recognized the 'liberal' doctrine of the autonomy of nature and culture. It has been against the rules to argue from a position of biological reductionism. But the goal of each tale has been a picture of human universals, of human nature as the foundation for culture. Ironically, reconstructions of human nature useful to feminists were derived from two of the theories most despised by socialist-feminist thought: functionalism and sociobiology. They have been criticized as ideological justifications of unjust economic and political structures, as rationalizations for the reproduction of present relations of the body and body politic. Obviously, as Rowell, Tanner, and Zihlman show, these theories can be deployed for other ends: to stress human and animal variability, complexity, capacity for change. Feminists can engage seriously, then, in the biosocial debate from within the sciences.

We must, however, be acutely aware of the dangers of using old rules to tell new tales. This is compatible with a larger refusal to pretend that science is either only discovery, which erects a fetish of objectivity, or only invention, which rests on crass idealism. We both learn about and create nature and ourselves. We must also see the biosocial sciences from the point of view of the process of resolving the contradiction between, or the gap between, human reality and human possibility in history. The purpose of the sciences of function is to produce both understanding of meaning and predictive means of control. They show both the given and the possible in a dialectic between the past and the future. Often, the future is given by the possibility of a past. Sciences also act as legitimating meta-languages that produce homologies between social and symbolic systems. That is acutely true for the sciences of the body and the body politic. In a strict sense, science is our myth. That claim does not in any way vitiate the discipline scientific practitioners impose on each other to study the world. We can both know that our bodies, other animals, fossils, and what have you are proper objects for scientific investigation, and remember how historically determined is our part in the construction of the object. It is not an accident of nature that our social and evolutionary knowledge of animals, hominids, and ourselves has been developed in functionalist and capitalist economic terms.8 Feminists must not expect even arguments that answer clear sexist bias within the sciences to produce adequate final theories of production and reproduction as well. Such theories still elude us, because we are now engaged in a political-scientific struggle to formulate the rules through which we will articulate them. The terrain of primatology is the contested zone. The future is the issue.