In which I conclude by presenting hopeful but not unrealistic scenarios of what can happen when enough people are saying of government-engendered problems, “This is ridiculous.”

RONALD REAGAN CAME to the presidency in 1981 having declared that his strategy regarding the Cold War was “We win, they lose.” It was seen as a foolish and dangerous position by everyone from academic Sovietologists to Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon. Presidents since the end of World War II had pledged themselves to no more than containing communism and, latterly, reaching détente with the Soviet Union. None had said anything remotely like “We win, they lose.”

Ten years later, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. When Western scholars subsequently got access to the Soviet government’s internal documents, it turned out that the Soviet Union in 1981 was already a hollow shell, with a sick economy and political institutions that set new standards of sclerosis. What had Reagan added to these difficulties? Scholars are still trying to determine the complete answer to that question, but it is already clear that Reagan poked a shaky Soviet system in some vulnerable places—by arming the mujahideen in Afghanistan with Stinger missiles; starting a technological arms race that the Soviet leadership knew it could not match (Star Wars was especially unnerving); and assaulting the Soviet Union’s pride rhetorically, from his “Evil Empire” speech (surprisingly dismaying to the Soviets, we have since learned) to his “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall” speech in Berlin.

For these and other reasons, the image of the Soviet Union changed, without and within. Before Reagan, the Soviet Union had been seen as one of the world’s two superpowers, and many thought it was the ascendant one. During Reagan’s time in office, the curtain was pulled aside, and the Soviet Union was exposed for what it was: a Third World country with nuclear weapons. The Soviets blundered into halfhearted, haphazard reforms, and an incompetent, divided, and dispirited nomenklatura finished the job without further assistance from the West.

What Reagan accomplished is analogous to what I want the defense funds to do: not pull down the US government (that seems excessive), but pull aside the curtain on one component of that government, the regulatory state, and expose the Wizard of Oz within.

Doing so might ultimately accomplish much more than plaguing the regulatory state. It could also change the zeitgeist. This is where the parallels with the Cold War are most apt. The Soviets took for granted that the arrow of history went only one way—they had added client states regularly since the end of World War II, and the West had never taken one back. Similarly, progressives have lived in a world where government constantly expands and conservatives can only slow its growth. If a significant portion of the Code of Federal Regulations were to become de facto unenforceable—if it can be seen that the reach of government can actually shrink, not just be slowed—all sorts of previously unthinkable things become possible. That’s why I have offered the preceding discussions of the rediversification of America in chapter 12 and of the promising conditions for change in chapter 13, to give a sense of how propitious the moment is. But propitious for what? How are all these positive forces going to work their magic? What happens next?

Sometimes predicting the broad shape of the distant future can be a fruitful way of backing into implications for what might have to happen in the interim. Specifically, let’s think about the overriding implications of growing wealth and advancing technology over the long term—two centuries, let’s say.

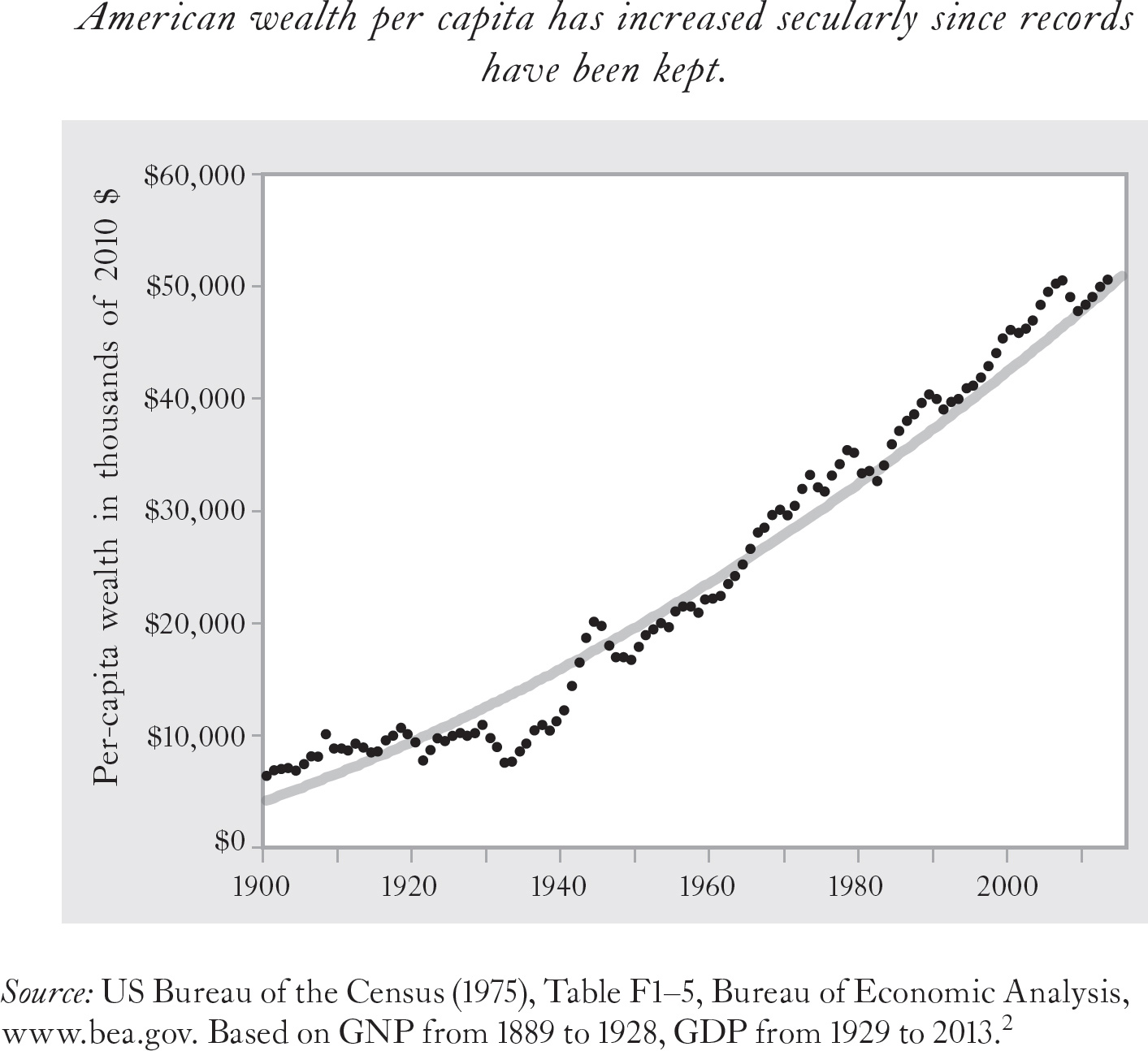

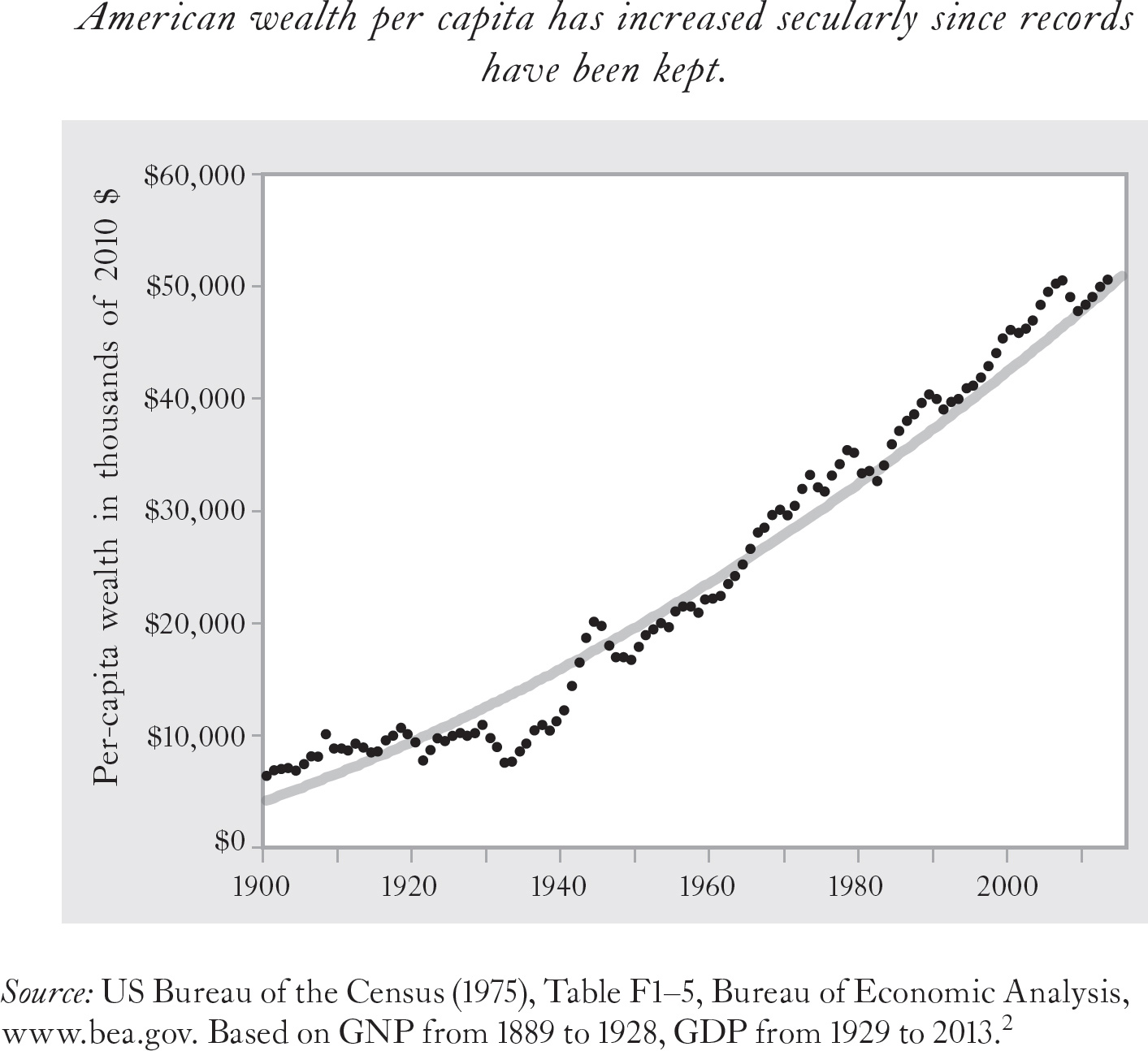

Economic historians have established that per-capita wealth was effectively flat for societies throughout the world from the beginning of the Christian era until the seventeenth century. Then, starting in England and the Netherlands, subsequently spreading across western Europe, per-capita wealth began to rise and has continued rising ever since.1 The same thing happened in the United States, starting behind Europe but growing at an even faster pace thereafter. The earliest systematic calculation of America’s national wealth goes back 125 years, to 1889. Here’s what the growth in per-capita national wealth has looked like since then:

Per-capita wealth has grown with remarkably close fidelity to the fitted trendline superimposed on the yearly data for 125 years. There have been anomalies—the Great Depression of the 1930s and the rebound during World War II and, more recently, the prosperity of the 1990s and early 2000s—but other times that have been perceived as boom years or fallow periods have been close to the overall trend.3 The consistency of growth gives reason to hope that it will take public policy of Soviet stupidity to bring that growth to a halt over the long haul—which is not to say that it won’t happen, but that it will require policymakers to ignore everything economists have learned about how wealth is created.

Let’s hope for the best, and assume that two centuries from now the upward trend has continued. It’s probably unrealistic to expect a continuation of the nonlinear trendline in the figure. But suppose that we grow linearly at the rate that has characterized the economy since the end of World War II. That would produce per-capita GDP in 2215 of almost $160,000 in 2010 dollars. Any subset of more than twenty years in the postwar era produces a projection greater than $150,000 per person. Today’s per-capita GDP is about one-third of that. What couldn’t we do today if we had three times the wealth?

It’s not just wealth that we can expect to transform the range of the possible. The information technologies that have revolutionized daily life over the last three decades will look primitive compared to those of two hundred years from now. We will fully understand the human genome, and along with it deep truths about how human beings flourish that can guide public policy. For that matter, humankind will long since have acquired the ability to modify its own genome. The natural outcome of this new knowledge will be to enhance human capabilities and empower the individual in fabulous ways. It is, of course, possible that some nightmarish political dystopia will have triumphed, but that is not the most plausible scenario.

National wealth that dwarfs today’s, and technology that gives the individual access to total information and the capacity to apply that information to everyday life: Under those conditions, it is unimaginable that Americans will still think the best way to live is to be governed by armies of bureaucrats enforcing thousands of minutely prescriptive rules. Somehow, the American polity will have evolved toward more efficient ways of working and living together. In the language I have used throughout this book, America will do a better job of leaving people free to live their lives as they see fit as long as they accord the same freedom to everyone else.

We aren’t able to predict exactly how the miracle will have happened, but we may reasonably predict that it will have happened two centuries from now. There will be too much money and too many technological resources to make today’s leviathan government necessary. Think in terms of the problems that gave rise to the EPA, OSHA, Dodd-Frank, and the Affordable Care Act, and how few of them are likely to survive until 2215. Of course new problems will also appear, but greater wealth and technology really do reduce the net number of purely technical difficulties. Compare 1815 and 2015 in terms of the technical difficulties of preparing a family meal, traveling from New York to Boston, curing a headache, or running a safe and environmentally friendly foundry.

That optimistic view leaves open the question of how the evolution away from today’s intrusive state can get started now. My generic explanation is simple, again inspired by Stein’s law, “If something can’t go on forever, it will stop.” I propose that people don’t naturally continue doing stupid things forever. A great deal of progress in our current situation requires little more than that we stop doing stupid things. That, in turn, requires that reasonable people with a wide range of political views agree regarding a given state of affairs, “This is ridiculous.”

A Government of the Factions, by the Factions, and for the Factions

This book has described many problems of which reasonable people will already say “This is ridiculous.” It is ridiculous for a nation to have a tax code four million words long. Ridiculous to have bureaucracies with twenty-two management layers. Ridiculous to take ten years to decide court cases.

The same may be said of many of the public-policy problems that vex us. For example: Some schools serving disadvantaged children are disorderly and sometimes dangerous, even in cities where per-student expenditures on schools are high. That’s ridiculous. What percentage of parents would voluntarily send their children to such a school? One percent? Half of one percent? A tenth? It’s not that the problem is unsolvable. Human beings have known how to operate orderly schools for millennia. Disorderly students are first punished and, if they don’t mend their ways, expelled.

Therein lies the reason that we have the problem. People can’t agree on what is to be done with the troublemakers. But there are known solutions—not perfect ones, but solutions that achieve the overriding goal of allowing students who want to learn to do so. And so I repeat: When some schools have a problem that hardly any parent, including the most progressive, would tolerate in a school that their own children attended, and when there are known solutions, it is ridiculous that any child must attend a disorderly and unsafe school. We need only muster the will to make them orderly and safe. And so progress should be possible. But it isn’t.

Consider the case of the tax deduction for mortgage interest. It is regressive. That’s not disputable. Richer people tend to have more expensive houses and, since the tax break exists, it is usually to their advantage to carry big mortgages. To be specific, about a third of the total mortgage tax deductions goes to households in the top 5 percent of income.4 People can argue from principle for progressive taxes or flat taxes, but no political philosophy tries to make a principled case for a regressive tax. And so it should be possible to get rid of the mortgage interest deduction. But it isn’t.

Or consider a more abstruse example of something that’s ridiculous. It’s ridiculous that the cost of routine health care has not been falling for decades.5 By routine health care I mean treatment of the garden-variety ailments and accidents that account for almost all of our visits to a physician’s office: things like a sinus infection, strep throat, a gash that needs closing, a broken bone, a rash, childhood diseases, a bad sprain, or GI distress. The real costs of dealing with such problems has typically been going down. That the costs being charged for dealing with them have gone up at all, let alone soared, should be a scandal.

The biggest reduction in costs has been produced by antibiotics, which have consigned many painful, expensive, and sometimes fatal ailments to medical history. But the reduction in costs has occurred in almost everything that physicians do. Wounds that used to require stitching often can be closed with adhesives. Blood tests that used to require labor-intensive analysis are now done automatically by machines. Ulcers that used to require surgery are now controlled through over-the-counter pills.

It’s not just garden-variety ailments that are now cheaper to fix. Cost per outcome has been dropping for many medical technologies. Laparoscopic surgery is an example: The cost of laparoscopic instruments is greater than the cost of a scalpel and retractors for traditional surgery, but the patient goes home much sooner, saving hospitalization costs. Those savings occur with every operation, while the cost of the laparoscopic instruments is amortized over many operations.

Even the labor costs of health care should be falling, because productivity per employee has been rising. Remote monitoring of symptoms means that it takes fewer nurses to keep track of more patients. Improvements in technologies for everything from hospital beds to food preparation increase the productivity of support staff. If other forces weren’t getting in the way, the cost of keeping a person in a hospital bed for a day would be going down.

That the charges for routine health care have soared has nothing to do with the underlying real costs but with the medical cartel, malpractice insurance, regulations, and other ways in which the health-care industry is segregated from ordinary market forces that would produce lower costs. In light of the reality that most costs of routine health care have been dropping but the prices we actually pay for such health care have been soaring, progress should be possible. But it isn’t.

Every one of the ridiculous things in these examples has a constituency that is able to block a sensible, affordable fix for it—not because the fix wouldn’t work but because for some reason, sometimes a complicated reason, implementing the fix would not be in the self-interest of teachers, physicians, health-insurance companies, or the politicians’ own political survival. Currently, their interests must be satisfied before any fix becomes possible.

We have reached precisely that state of government that the founders most feared: one in which factions have taken over—factions as Madison defined the word in Federalist #10: “a number of citizens … who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” The five chapters of Part I may be read as an extended description of Madison’s nightmare come true. We now have a government of the factions, by the factions, and for the factions. Or, if you prefer the modern term, government of special interests, by special interests, and for special interests.

Breaking the Logjam

Now imagine a time in the future when somehow the grip of special interests has been loosened. What needs to have happened? First, when a problem was sufficiently ridiculous, people of different ideologies must have learned to put aside their differences long enough to collaborate. For that learning process to have taken place, they must have been put in situations where they have gotten used to being on the same side. To have gotten used to being on the same side, they must have had a common adversary that brought them together. That’s where the activities of the defense funds come in.

The defense funds will be defending everyone who is being harassed by the regulatory state, and its beneficiaries will include many liberals.[6] Liberals and conservatives will often find themselves in agreement that certain regulations are ridiculous. And in that cumulative experience, over a matter of years, will come recognition of a truth: To be a liberal doesn’t require that one think that everything the government does is justified. It is possible to oppose the government on a specific issue without ceasing to be a liberal. Similarly, conservatives will have a cumulative experience of being on the same side of a dispute as liberals are.

Citizens from different places on the political spectrum will have a cumulative common experience of treating the regulatory state as an adversary, becoming accustomed to the fact that elements of the federal government have become “them,” not “us”; that the regulators are not our elected representatives but our unelected minders. Once it becomes normal for liberals as well as conservatives to react to stupid regulations with “This is ridiculous,” the way will have been opened for larger changes. Systematic civil disobedience is the blunt instrument from outside the system that will mobilize forces for change independently of the system’s sclerosis.

I want to emphasize that I am not envisioning a time when liberals decide that conservatives were right after all. On the contrary, the key is that both liberals and conservatives (and we Madisonians) understand that a common cause against stupid government regulations exists outside the normal left-right policy continuum.

This vision sounds idealistic only because of the extreme political polarization of our era. Historically, the American norm was for politicians to say terrible things about one another for public consumption while enjoying cordial personal relationships behind the scenes, quietly recognizing common ground, and cutting deals. Among the public at large, political differences among friends were just that—differences of political preferences, not a Manichean divide between the forces of light and the forces of darkness. If done properly, the defense funds’ work will be equally welcome to liberals and conservatives who are having problems with the government, and the Manichean divide will have been blurred at least a little.

There is an analogy to be drawn between the defense funds and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). From its founding in the 1920s until it gradually succumbed to political correctness after the 1970s, the ACLU transcended politics in a similar way. Its purpose was to defend constitutional rights, especially free speech, against all challenges, and in that effort its clients included Communists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Ku Klux Klan, and anyone else who was being silenced. There was a liberal cast to the ACLU’s image, just as the defense funds will have an antiprogressive cast (since they will be locked in combat with the regulatory state), but the ACLU was not considered partisan in the usual sense of that term, nor will the defense funds be considered partisan. If you’ve got the government on your back for no good reason, the defense funds will be on your side no matter what your politics may be.

That’s the environment in which the logjam can begin to break up—in which the factors that make this a propitious moment, described in the preceding chapters, come into play. People who have strong ideological convictions can begin to say, in effect, “I know some of my political friends will get mad at me for saying it, but this is ridiculous.”

But for the logjam to break, there need to be signs that both ends of the political spectrum are participating, and this puts a special burden on people on the right. Most public policies that have evolved into the obviously ridiculous were originated by the left. If liberals think that giving an inch on the ridiculous things is going to be a process where they do all the compromising while the right sits tight, we’re going to remain in our respective trenches, barbed wire coiled around our positions, machine guns sighted in. There has to be evidence of good faith on both sides. We need a pact that says, “Here are some policies that we are all willing to put in the ‘this is ridiculous’ category. Some of them are allied to issues we favor; others are allied to issues that you favor. We’ll fix the ridiculous things while agreeing to disagree on the allied issues.”

How might the logjam be broken in practice? As always, I have no confidence in my specific predictions, but let me offer three ridiculous states of affairs as examples. One requires liberals to give ground. Another requires conservatives to give ground. The third requires liberals to disavow progressives and Madisonians to disavow social conservatives.

It’s ridiculous that towns and cities can’t afford to provide basic services.

Many towns and cities around America are doing fine. They have enough police and firefighters, potholes get fixed, the garbage is collected regularly, and all these good things are done within a balanced budget. Meanwhile, as the discussion of the collapse of the blue model noted in chapter 12, other towns and cities are going bankrupt. Many that are not bankrupt are providing inferior basic services.

The explanation is seldom that tax revenues are not large enough. More commonly, two kinds of overspending have occurred. First, the city government has installed discretionary programs over the years, often with start-up grants from the federal government. Now they find they can’t afford them anymore, but the programs have factional support that keeps the city council from ending them until the heat from the electorate becomes unbearable. Often, only the prospect of imminent bankruptcy can generate that heat.

Second, personnel costs in these cities have gone through the roof. The reason personnel costs have gone through the roof is because of contracts negotiated between a public employees’ union that wanted more money and benefits, and municipal politicians who were elected with the support of the very union that was making the demands.7

That’s ridiculous. For union-management negotiations to work, management must have a strong incentive to resist excessive demands. A mayor and city council don’t. Even when they are not beholden to the employees’ unions for political support, they don’t have anything approaching the same incentive to fight union demands that motivates the CEO and executives of a private company—elected officials can always grant concessions in unobtrusive ways (for example, pension and overtime benefits) that don’t create political problems for them. Even someone as unimpeachably liberal as Franklin Roosevelt and someone as unimpeachably pro-union as George Meany thought that unionization of government workers was ridiculous.8

It would go a long way toward breaking the logjam from the left if liberals started joining with conservatives in recognizing that public employee unions are inherently inappropriate. The collapse of the blue model is going to help push them in that direction. Liberals who do so wouldn’t have to alter their support for unions in the private sector or any of their other political beliefs. They just have to want to provide their fellow citizens with affordable police and fire protection, well-maintained streets, prompt garbage pickup, and other basic city services. There’s nothing illiberal about any of that. They don’t have to strip public employees of the job security that has traditionally led some people to find government jobs attractive. They just have to return to an older model of city governance that many other cities around the country have continued to practice successfully. It could happen.

In a country as rich as America, it is ridiculous that anyone lacks the means to live a decent life.

The potential for breaking the logjam from the right is for conservatives to accept that large income transfers are a reality of advanced societies, to stop complaining about them, and to begin actively trying to improve the way they are accomplished.

It’s worth spelling out how ridiculous the present state of affairs is. It’s not that the United States is too stingy with its income transfers. In 2012, the United States transferred more than $2 trillion to individuals to provide for retirement, health care, and the alleviation of poverty, yet we still have millions of people without comfortable retirements, without adequate health care, and in poverty. Only a government could spend so much money so ineffectually. Eliminating cash poverty altogether without adding a dime to the budget would be technically easy right now.

The devil is in the details, of course, and this is not the place to deal with them. I want to make three simpler points about why Madisonians should be as pragmatic about welfare as liberals should be pragmatic about public employees’ unions.

First, it’s time for us to let go of some good arguments that it’s the liberals’ fault we’re in this mess. Two things can be true at the same time:

• The perverse incentives of the welfare state have created dependency and human suffering. If we could go back and change history, we would have a healthier, happier society.

• We can’t go back and change history.

Second, changes in the labor market have changed the moral arguments in favor of redistribution for the working population. At the top end of the economy, to have a high level of cognitive ability has become far more valuable over the course of the last half century. This is most obvious in the IT and financial worlds, but it applies to virtually all professions and managerial jobs. Meanwhile, the economic value of many blue-collar and midlevel white-collar jobs has stagnated or dropped, not because of policy or market failures but because so many jobs can be done as well, and cheaper, by machines. The number of such jobs continues to grow, now reaching well into white-collar jobs. We can argue about how much we can change our fortunes in life through industriousness and perseverance, but IQ is pure luck of the draw. Faced with a situation in which national wealth keeps growing but a substantial portion of the population is doomed to stagnant wages through no fault of their own, we need to figure out ways to augment the income of working people who are doing everything right.

Third, even though income transfers always have negative incentives, the magnitude of those problems can vary widely depending on how the transfers are administered. In a previous book (In Our Hands), I argued that a basic guaranteed income can be structured not only so that the negative incentives are minimized but so that positive incentives for the revitalization of civil society are introduced. Others, notably Congressman Paul Ryan, have introduced other approaches for making income transfers a positive as well as a problematic element of public policy.9

For all these reasons, it is time for conservatives to make some of their political friends mad at them and acknowledge that, in a country as rich as America, it is ridiculous that anyone lacks the means for a decent life. As evidence of good faith, it would go a long way toward helping to break the logjam. And, as Henry Kissinger said in another context, it has the added advantage of being true.

In a nation as diverse as America, it is ridiculous to impose one-size-fits-all national solutions for policies that involve morally complex cultural differences.

So far, I have tried to use examples of “it is ridiculous …” that can withstand challenges (at least to my own satisfaction). This one cannot. The alternative position, that it is our duty to search for the One Best Way on any policy issue that involves a moral principle, and to hold all Americans to it, is defensible. If one makes that argument with regard to something like slavery, I agree with it. But which moral issues fall into the category of ones on which all civilized people should agree?

I would argue that not one of the hot-button issues that have had social liberals and social conservatives screaming at one another for decades falls into that category. Not abortion, not gay rights, not any of the others. All of them involve bundles of competing moral dimensions that reasonable and virtuous people will weight differently, leading them both to different conclusions and to different kinds of lives.

We have been treating those issues as a culture war, as if the only solution is for one side to win and the other side to lose. But why? The only people who need to feel that way are the absolutists for whom one side is in sole possession of truth, the other side’s position has no legitimacy, and any tolerance of diversity is morally wrong. The polls indicate that the great majority of the American people are not so absolutist. Why not instead celebrate diversity, celebrate our increased ability to choose places where we can live life as we see fit, and start to treat the locality as the proper unit of aggregation for working out peace terms in the culture war? It can’t be done officially, but to a substantial degree it can be done de facto.

The ground rules are simple. No one may deny to others the freedom to live their lives as they see fit, and that means strict enforcement of laws against the acts by which people have denied that freedom to others in the past, from physical violence to throwing garbage on people’s lawns and everything in between. But—to take an example that has recently been in the news—if a photographer is personally opposed to gay marriage, forcing that photographer to work a gay wedding is unnecessary. Here’s where the de facto part comes in. What I’m proposing is not a campaign to repeal antidiscrimination laws but the restoration of a frame of mind that once again leads people to say of others’ choices, “It’s a free country.”

Restoring this de facto freedom of choice will require some introspection within both the left and the right.

On the left, it is time for a distinction to be made between liberals and progressives. As matters stand, the two terms are used interchangeably, but in fact they refer to two streams of thought that emerged from the Progressive Era at the beginning of the twentieth century.

To recapitulate from the first three chapters, progressive intellectuals were passionate advocates of rule by disinterested experts led by a strong unifying leader. They were in favor of using the state to mold social institutions in the interests of the collective. They thought that individualism and the Constitution were both outmoded.

That core impulse to mold all of American society in the One Best Way still animates progressives today. It is primarily found among those who are described as the hard left. They do not constitute a large proportion of Democratic voters. But there is no denying their totalitarian streak. In many universities, where the progressives are most dominant, they have nearly shut down intellectual debate on many issues, making certain that the faculty and even visiting speakers pass progressive litmus tests.

But the Progressive Era also consisted of a “good government” movement that went in a different direction, fighting political machines in the cities and advocating for more complete democracy. The Seventeenth Amendment mandating the direct election of senators was a product of that aspect of the Progressive Era, as were state laws—California’s, for example—allowing ballot initiatives that pass binding laws without the approval of the legislature. This stream of thought produced a political legacy that corresponds to the liberalism of the much larger proportion of Democrats who are usually described as part of the moderate left. Liberals (that’s what I want to call them) were at the forefront of the civil rights movement, and also of the broader civil liberties movement that defended free speech in all circumstances.10

I, along with other Madisonians, disagree with the liberals’ policy agenda. They think that an activist federal government is a force for good and approve of the growing welfare state. But most of them are personally tolerant and are willing to engage in civil discourse. They still believe that the individual should not be sacrificed to the collective and that people who achieve success should be praised for what they have built. I’m not happy that liberals like the idea of a “living Constitution,” but they still believe in the separation of powers, checks and balances, and the president’s duty to execute the laws faithfully. Liberals can be brought to support freedom of choice on complex moral issues. Progressives cannot.

On the right, we have a similar split between what the press usually describes as “conservatives” and “social conservatives.” It’s more nuanced than that. Many people who are in favor of limited government and free markets describe themselves as conservatives because they also hold conservative views on marriage, abortion, pornography, drug use, and other social issues. But many of these conservatives do not want the federal government to legislate on these issues. These conservatives fit my definition of Madisonians. The social conservatives who are the right’s version of the progressives are those who want to enact their social agenda nationwide.

Progressives and social conservatives are minorities of their respective sides of the political divide, but they drive the political polarization. Here’s my proposition: Liberals have to begin distinguishing themselves from progressives, and Madisonians have to begin distinguishing themselves from social conservatives, openly and explicitly rejecting the aspects of the progressive and social conservative agendas that seek to impose their respective worldviews on the entire nation. If that were to happen, not only would freedom of choice on complex moral issues have a chance to evolve, but the rediversification of America would make it virtually inevitable. The return of that freedom of choice would in itself constitute a major revival of the American project.

As I close these speculations about the prospects for rebuilding American liberty, I am conscious of three quite different reactions, each reasonable, that readers might have.

The first, of course, is that I am wrong in my diagnosis of America’s problems and wrong in my prescriptions for their solution. To that, I can only say: Fair enough; you’ve heard me out.

The second reaction is that I’m far too optimistic about how much effect the defense funds could have. It’s unlikely that they will ever operate at anything approaching the scope I have described. Even if they did, it’s unlikely that they would have the transformative effects I envision—Goliath would brush them off without even noticing. To that, my reply is: Attacking the regulatory state through the legal system is the only option for rebuilding liberty. You are not going to stop the growth of government through the political process, let alone reverse it. It can’t be done, for the reasons I described in chapters 4 and 5. Systematic civil disobedience may be a long shot, but it is, in fact, a shot. It could work. The bureaucracies of the federal government really are sclerotic. Their thousands of edicts really can’t be enforced without our voluntary compliance. Withholding that compliance really could have transforming effects on the political landscape.

The third reaction concerns something that I too have worried about: I’m oblivious to the dangers of success. By definition, a successful program of systematic civil disobedience would further erode the legitimacy of the federal government. Is that something we can afford to risk? Political polarization is at unprecedented levels, with large portions of the electorate convinced that the other side is not only mistaken in its political views but evil. The nation is already riven by a new kind of class divide, with a lower class and an upper class that are culturally separated in unprecedented ways. America’s ethnic mix is in the process of a historic change. In this situation, shouldn’t we be seeking reconciliation and unity, not encouraging America’s balkanization? Perhaps Sam Rayburn and Lyndon Johnson were right: we should indeed seek to become one America, with no East, no West, no North, no South.

Part of my response is that we don’t have the option of restoring the consensus that seemed to characterize the 1950s. We have already come apart. We must deal with that reality. More fundamentally, America was not meant to be one America. It was intended to accommodate diversity. I like David Gelernter’s way of putting it: “The founders designed a vast garment for America that hugs where it should hug and stretches where it should stretch; each state creates its own society, and the Constitution stitches them all together into a comfortable, sensible union suit.”11 Restoring that design is not something we should see ourselves as forced to do by circumstances, but something that we urgently want to do. Eroding the legitimacy of the federal government as it now exists is essential to avoid an America that is defined geographically as it is now but is no longer spiritually America.

The disappearance of the authentic America would be an immeasurable loss. America isn’t the only great place to live. I can think of a dozen countries, just among the ones I know, where I could have made a satisfying life for myself. The loss of the way of life of any one of them would make the world culturally poorer.

But that truth should not obscure another one: America is unique not because of the kinds of cultural particularities that make every country different from every other country. If America becomes like the advanced social democracies of Europe, as it threatens to do, it would mean the loss of a unique way of life grounded in individual freedom.

No other country throughout the history of the world began its existence with a charter focused on limiting the power of government and maximizing the freedom of its individual citizens. Even after we set the example, no other new country subsequently has followed it. Neither has any old country modified its charter to become more like ours. The United States of America from 1789 to the 1930s is the sole example of truly limited government anywhere, at any time. Under that aegis, we also happened to go from a few million colonists along the East Coast of North America to the richest and most powerful nation on Earth. We became a magnet for people around the world who wanted to share in the opportunities afforded by American freedom. But these achievements were ancillary to the most important of all:

America’s unique charter produced a unique culture. American exceptionalism is not an idea that we invented to glorify ourselves but a reality recognized around the world at the time of the founding and for well over a century thereafter.12 America’s unique culture—its civic religion, as I have called it—made for a unique people. Some of our characteristics are not to everyone’s taste, but I love them all. Our openness. Our passion to get ahead. Our passion to see what’s over the next hill. Our egalitarianism. Our over-the-top patriotism. Our neighborliness. Our feistiness. Our pride. Our generosity. All wrapped in our individualism.

Those American qualities are fading, once-bright colors left too long under an alien sun. The words from Alexis de Tocqueville that I used as an epigraph for By the People increasingly describe us today. The government now “covers the surface of society with a network of small, complicated rules, minute and uniform.” As Tocqueville predicted, we have experienced not tyranny but a state that “compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people.”13

Systematic civil disobedience offers a chance to revive those colors. Perhaps not to the primary intensity they once had, but enough that we are once again different from everyone else, uniquely American. If that process diminishes the majesty of the American government, I don’t care. Our government is not supposed to be majestic. Neither does the government command our allegiance independently of its own allegiance to its proper role. The federal government was created with one overriding duty: to allow us to live freely as we see fit, as long as we accord the same right to everyone else. It has betrayed that duty.

America can cease to be the wealthiest nation on Earth and remain America. It can cease to be the most powerful nation on Earth and remain America. It cannot cease to be the land of the free and remain America. I am not frightened by the prospective loss of America’s grandeur. I am frightened by how close we are to losing America’s soul.