CHAPTER 4

The Matter of the Mind

The previous chapters brought us from the nineteenth-century discovery of human antiquity to present-day enquiries into the curious interaction of two species of Homo during the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic Transition in western Europe. We saw that, although modern human behaviour of the kind practised by the first Homo sapiens communities to reach western Europe was put together piecemeal in Africa and the Middle East, something rather special happened in the European cul-de-sac. Circumstances peculiar to that region created an illusion of the sudden appearance of a package deal of symbolic activity:

– refined stone-tool technology that went beyond the purely functional to signal group identity,

– body adornments that conveyed information about personal and group identity,

– elaborate burial of certain dead,

– fully modern language, and

– the making of images.

I also began to argue that this behavioural package, however slowly and sporadically it may have been assembled in Africa, presupposes a kind of human consciousness that was alien to the Neanderthals and that permits conceptions of an ‘alternative reality’. We now need to investigate theories of how human intelligence evolved through the millennia, but we also need to go further and consider the role of human consciousness. We stand on the threshold of a new kind of enquiry that is concerned with the human mind, not just with stones and bones, the material remains of human activities. At this point, some archaeologists begin to feel uneasy: what they deride as ‘palaeopsychology’ is, for them, anathema.

Their discomfort derives from too rigid a devotion to what are, I believe, restrictive methods of research. Indeed, enquiry into the nature of Upper Palaeolithic mind and consciousness demands further consideration of methodology. We need a method different from the comparatively simple one we used in discriminating between the early hypotheses about the purposes of Upper Palaeolithic image-making, such as sympathetic magic and the supposed existence of a prehistoric mythogram. The criteria that we employed for evaluating hypotheses remain important, but we need to go beyond them. As soon as we move, as we began to do in Chapter 3, from fairly restricted fields of evidence to much broader considerations of human consciousness, we need to explore neuropsychology – the study of how the brain/mind works – in addition to technology, the archaeology of prehistoric settlement patterns, economic activity, and the other components of early human life with which we have so far been principally concerned. This widening of interest means that we now have to accommodate a new strand of evidence.

Strands of evidence

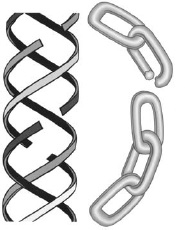

The intertwining of numerous strands of evidence is a method of constructing explanations that philosophers of science recognize as being closer to what actually happens in daily scientific practice than the formal, sequential testing of hypotheses, the method about which researchers frequently talk. Alison Wylie, 1 herself a philosopher of science, has advocated this ‘cabling’ method in archaeology. To illustrate the difference between ‘cabling’ and other kinds of argument she points out that some arguments are like chains: they follow link after logical link; if one link fails through lack of evidence or faulty logic, the whole argument breaks down (Fig. 23). This is a difficulty that faces researchers who tackle the kind of enquiry that we are pursuing. Archaeology is, almost by definition, the quintessential science of exiguous evidence. We have to devise ways of getting around the gaps that – understandably enough – punctuate the entire sweep of the archaeological record.

Wylie points out that, in practice, archaeologists overcome this problem by intertwining multiple strands of evidence. The value of this method is that each of the strands is, in its own way, both sustaining and constraining. These two characteristics of evidence require a word of explanation.

23 Two types of argument. Cable-like arguments that intertwine a number of strands of evidence. Chain-like arguments that proceed link by link. Cable-like arguments are sustainable even if there are gaps in some strands.

A strand is sustaining in that it may compensate for a gap in another strand. For example, the archaeological record itself may not suggest an explanation for a particular feature discovered in an excavation (say, a cramped stone structure), but the ethnographic record of small-scale societies around the world may well suggest an explanation (people seeking contemplative solitude are known to have built similar structures). If a certain human activity in a hunter-gatherer community in one part of the world led to physical evidence similar to the archaeological discovery, the same relationship between activity and material record might have occurred in a hunter-gatherer settlement in the deep past. Having been enlightened by ethnography, a researcher can return to the archaeological record (perhaps at the same time exploring some other strand of evidence) to search for any data hitherto unnoticed that may support or contradict the ethnographic hint. The ethnographic evidential strand, along with other kinds of evidence, may thus help to ‘cover’ a gap in the archaeological strand.

The ‘cabling’ method is useful in another way as well: it is constraining in that it restricts wild hypotheses that may take a researcher far from the archaeological record. An archaeologist may, for instance, think that a severe drought led to the abandonment of a human settlement in a climatically marginal environment, but palaeo-climatic evidence (another strand that depends in part on the analysis of ancient pollen) may show that no such drought occurred.

This is the method that researchers adopt – whether they acknowledge it explicitly or not – when they cast around for hints as to what may have been happening to the human brain/mind during the Transition. They look for strands of evidence beyond the archaeological record itself. Some turn to the study of apes and chimpanzees and the ways in which they can, or cannot, learn to communicate; they are, after all, our nearest hominid relatives. Other researchers explore the construction of artificial intelligence, and the ways in which scientists are trying to build thinking machines. Others study how children learn and acquire language in the hope that that process may in some ways parallel the way in which the human species learned to think and use language. Still others examine the brains/minds of mentally impaired or brain-damaged people in the hope that their fragmentary minds may cast some light on an early stage in the evolution of the human mind. None of these approaches has, at least to my way of thinking, contributed much to our understanding of how the human brain/mind came to be as it is today. They are fascinating in their own right, but apes are not frozen ancestors of human beings; children do not have the brains of archaic human beings; damaged brains are damaged anatomically modern brains not precursors of modern brains. Finally, even if scientists were able to construct a machine that would function just like a human brain, it would not be a brain and would therefore not assist us in explaining the evolution of the human brain. This may seem an unduly cavalier dismissal of much valuable research. It is not that I totally reject all this work; I just feel that we can proceed with our investigation of Upper Palaeolithic art without exploring all these controversial avenues.

The brain/mind problem

Some common, frequently used words are extraordinarily difficult to define. We have noted the problem of defining ‘art’. ‘Consciousness’ is another such word. We all know what it means – until someone asks us to define it. One of the sources of this difficulty is that consciousness is a historically situated selection and evaluation of mental states from a wide range of potential states. It is not a universal, timeless ‘given’. As before in this book, I side-step the tedious task of attempting to define the slippery word in a formal way. Instead, I allow an understanding of the word to emerge from a series of observations.

Two things we do know are, one, that the brain/mind evolved, and two, that consciousness (as distinct from brain) is a notion, or sensation, created by electro-chemical activity in the ‘wiring’ of the brain. These two observations guide much of the following discussion.

Enlarging on the first of these points, we can say that the brain/mind did not suddenly appear ex nihilo. The origins of the human brain/mind must lie deep in the past. Moreover, the beginnings of the brain/mind must have been shaped by conditions of survival that, in our modern Western society, no longer exist. That being so, we need to turn to Darwin and his insights into the mutability of species and the effects of natural selection – and, of course, also to more recent evolutionary theory that builds on Darwin’s well-laid foundation.

The second observation is rather different and requires more comment. If we are speaking of evolution, we are speaking – essentially – of the human body, our physical, material make-up of bones, blood, tissue, brain matter. By contrast, mind is a projection, an abstraction; it cannot be placed on a table and dissected as can a brain. Nor, it seems, can mind be placed on a philosophical table and defined and described. Indeed, the age-old mind/body problem continues to niggle despite the ingenuity of generations of philosophers.

The issue is most famously associated with René Descartes (1596–1650), a French-born thinker who lived most of his life in Holland. In view of the issues I discuss later, it is worth noting that Descartes said that he derived his ambition of designing a new philosophical and scientific system not from rational, lucid thought but from a series of dreams. That contradiction derived from the duality of his thinking. On the one hand, he developed philosophical and scientific theories that were rooted in rigid mathematics and the material world. On the other, his system was posited on the existence of a divine, benevolent creator. Out of this contradiction grew his well-known ‘Cartesian dualism’ that proposes the existence of two radically different kinds of substance: material substance (rocks, trees, animals and the human body) and ‘thinking substance’ (the human mind, thoughts, desires). From this duality arises a notion that the ‘self’ (more or less what we are calling consciousness) is something non-material and that it in some way operates the brain (which is material), rather as a puppeteer manipulates a puppet. The English philosopher Gilbert Ryle (1900–76) summed up this notion in his famous phrase ‘The Ghost in the Machine’. Descartes’s idea persists in what is now called ‘attributive dualism’, the doctrine that psychological phenomena cannot be reduced to a physical foundation. Whilst there is some sense in this kind of opposition to a reductionist explanation of mind, I believe that any persuasive explanation must refer to the form and functioning of the brain, the matter of the mind. The ghost hidden in the machine is a cognitive illusion created by the electro-chemical functioning of the brain.

That said, we have to admit that, despite the current plethora of studies of human consciousness, we still do not know how the functioning of the brain produces human consciousness. We do have a much better understanding of what happens in the brain than we did 20 years ago, even though, as Ian Glynn points out in his elegant and erudite book, An Anatomy of Thought, much remains mysterious.2 More pessimistically, there are those who argue that the problem will never be solved. For them, consciousness is like religion: if you have it, you cannot study it. Put another way, our cognitive abilities do not allow us to understand our cognitive abilities. It may be true that, if you have religion, you cannot study it, but it is a false analogy to go on to argue that our consciousness prevents us from understanding our consciousness. The fascinating issues of consciousness, self-awareness, introspection, insight and foresight remain, but, like other fields of great interest to which I have referred, they are not the destination of our present enquiry. Fortunately, we can circumnavigate them and examine the debate that surrounds relationships between brain, mind and the earliest art.

Minds and metaphors

When we speak of the brain, we are on fairly solid ground. We can literally dissect a brain and find left and right hemispheres, the cortex, the hippocampus, synapses, neurotransmitters, and so forth. But, when we come to attempt the same kind of process with the mind and consciousness, we are forced to adopt a different procedure altogether. Inevitably, or so it seems, we are obliged to use metaphors and similes: we have to compare what we imagine to be the human mind to something simpler and something with which we are familiar. So the mind may be thought of as a blank slate on which, from birth, information is written by a process of learning. Or we may think of it as a sponge, soaking up knowledge, retaining it, and then squeezing it out again. Or, much more popularly today, we may think of the mind as a computer that has hardware (its neural make-up, which some like to call ‘wetware’) and software (the programmes that make it work). Some computers are more powerful than others: they can store more information and perform more complex tasks. So the minds of early hominids were like simple computers; ours are more powerful. A newer and increasingly influential metaphor, one that we shall examine in more detail, is that of a Swiss army knife, an instrument that contains a number of blades and gadgets, each designed to perform a specialized task.

It is important to remember that all these understandings are no more than metaphors: they have no foundation in physical evidence. The various components of a computer, for instance, are not paralleled by physical, discrete parts of the brain that can be dissected in the same way that a computer can be dismantled; the brain with its intricate neural pathways is more complex than that. This is a very real problem. Some metaphors are more attractive than others for a variety of reasons: not only are some more evocative, even more emotive, than others; in addition, some spawn sub-metaphors that seem to correspond to components of the mind that we are trying to explain. So it is that a computer’s hard drive may be likened to our memory; the keyboard to our organs of perception; the screen to modes of expression. When this sort of thing happens we may feel that we are indeed explaining the phenomenon of mind. But we are not. We are merely playing with words that have no correspondence in the material world in which the brain exists.

With these caveats in mind, we can turn to the most recent and widely discussed explanation for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic Transition and the two metaphors of mind on which it is built – Swiss army knives and cathedrals. How did these engaging metaphors come to provide so attractive an explanation and yet one that, I argue, misses the point?

Ecclesiastical Luddites

Most archaeologists agree that something drastic must have happened to earlier forms of the human mind to account for the west European evidence of the Transition, whether that change in mind took place in the Middle East and Europe or, as I have argued, principally in Africa. How else, they ask, can one explain the comparatively sudden appearance of an abundance of body decoration, burials and art? Point taken – at least in part. That is why some of these archaeologists turn to evolutionary psychology for insights into the stages through which the human mind evolved through the millennia of prehistory and up to its present state.3 They believe that they can bring their knowledge of the archaeological record into a mutually explanatory relationship with the stages of mental development that evolutionary psychologists propose. This research programme is certainly attractive, and the premise of mutual illumination between disciplines is surely valid.

Steven Mithen, an archaeologist at Reading University in England, is the most influential and thorough explorer of the relationship between the two disciplines. His ideas are comprehensively and clearly set out in his book The Prehistory of the Mind: A Search for the Origins of Art, Religion and Science.4 He (together with his evolutionary psychologist mentors) is principally concerned with intelligence and different kinds of intelligence. Without wishing to downplay the obvious significance of intelligence, I emphasize later the equal importance of consciousness.

I refer to different kinds of intelligence because the issue at the heart of evolutionary psychology is whether intelligence is a single, general-purpose ‘computer’ or a set of ‘computers’, each dedicated to a specific purpose. Evolutionary psychologists believe that the second of these propositions is the more likely because studies of non-human animal behaviour have shown that what is learned in one domain often cannot be transferred to another: there is little or no ‘transfer of training’. Evolutionary psychologists therefore speak of ‘mental modules’, ‘multiple intelligences’, ‘cognitive domains’, and ‘Darwinian algorithms’.5 The notion denoted by these phrases is perhaps most easily understood if we glance at one of Noam Chomsky’s ideas. He pointed out that children’s ability to learn complex language at an early age is probably in some way ‘wired into’ the human brain/mind.6 Other kinds of intelligent behaviour, such as facility with numbers, may be learned later – and less perfectly. There are therefore types of intelligence. Moreover, loss of facility in one domain, say language, perhaps through trauma, does not necessarily mean lack of ability in discerning social relations or in relating to the material environment: people who lose the power of speech can still move around without bumping into furniture.

The next key notion is ‘accessibility’. By this, evolutionary psychologists mean contact, or interaction, between mental modules. They argue that anatomically modern people have better interaction between modules than other animals. We are therefore able to perform more complex behaviours that extend across domains. Rather than a highly modular intelligence, we have a generalized intelligence. Researchers believe that the mental modules responsible for domain-specific behaviours are situated in specific neural circuits in the brain and that accessibility between them is achieved by neural pathways.

We need not examine all the variations of these fundamental propositions. Instead, we can move on to see what mental modules Mithen identifies and how he believes the generalization of these modules explains what happened at the Transition.

He proposes four mental modules:

– social intelligence,

– technical intelligence,

– natural history intelligence, and

– linguistic intelligence.

For instance, anatomically archaic people (who did not have generalized intelligence) could learn multi-stage procedures for making stone artefacts (technical intelligence), but this degree of complexity could not spill over into elaborate kinds of social relations (social intelligence). Indeed, he argues that there was little interaction, or accessibility, between intelligence modules prior to the Transition. The minds of archaic people were like Swiss army knives: they comprised a set of gadgets each dedicated to a specific task.

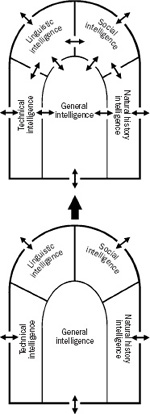

To illustrate an extension of this point, Mithen invokes a second beguiling metaphor, that of a cathedral (Fig. 24). The central nave represents general intelligence. Ranged around the nave are four chapels, each dedicated to one of the four mental modules. Prior to the Transition, there was little or no traffic between the chapels, though the possible linking power of rudimentary language in the Middle Palaeolithic should be taken into account. Then, at the Transition, there was a wave of vandalism that led to the demolition of the walls between the individual chapels and between them and the nave. This demolition allowed the transfer of intelligence from chapel to chapel and the enlargement of the central nave of general intelligence. The vandal that directed the destruction was fully modern language. The metaphor of language breaking down walls may be especially appropriate because, as researchers such as Chomsky7 and Bickerton8 have argued, the emergence of fully modern language must have been fairly sudden and not a gradation of barely discernible steps (though when this happened and what its immediate effects were remain to be determined).

24 Steven Mithen’s cathedrals of intelligence: (above) integrated intelligence that permits interaction between ‘chapels’; (below) modular intelligence with little accessibility between ‘chapels’.

At this time of neurological demolition, new mental abilities became viable. For instance, metaphorical thought became possible as a result of traffic between chapels. People could think of, say, social relations in terms of natural history intelligence – thus totemism was born: people could speak of human groups as if they were animal species. Similarly, anthropomorphism (the ascription of human characteristics to animals) was achieved by traffic from social intelligence through to the chapel of natural history: animals became like people. Then, too, for the comparatively complex subsistence strategies of the Upper Palaeolithic there had to be traffic between technical intelligence and natural history intelligence. Improved hunting equipment (technical intelligence) was of no use without integrating it with knowledge of the environment in which it was to be used and the behaviour of the animals to be hunted (natural history intelligence). All in all, human-environment interactions were transformed by this new mode of generalized intelligence.

Ingeniously, Mithen uses cathedral vandalism to explain the appearance of not only better adaptations, but also art at the Transition. He begins by proposing four cognitive and physical processes (not to be confused with the four intelligence modules):

– making visual images,

– classification of images into classes,

– intentional communication, and

– attribution of meaning to images.9

He then points out that the first three abilities are found in non-human primates. The fourth is the key ability, and it, Mithen argues, is found only in hominids. Yet, even though hominids such as the Neanderthals had it, visual symbolism arose, or at any rate flowered, only at the Transition (some researchers argue for an earlier date for the first signs of symbolic behaviour). So, what happened? Prior to the Transition, intentional communication and classification were probably sealed in the social intelligence chapel, while mark-making and the attribution of meaning, which both implicate material objects, were probably ensconced in chapels of non-social intelligence. At the Transition, accessibility between chapels made art possible by allowing intentional communication to escape into the domain of mark-making.

Some reservations

Evolutionary psychology as a sub-discipline has its critics.10 Unfortunately, there is a muddying of the waters with political correctness. Some critics find that the tenets of evolutionary psychology are uncomfortably close to freemarket economics, which they abhor. That observation has some support, but any scientific proposition must be accepted or rejected on rational grounds, not on its perceived social consequences.

This is a point that I bear in mind as I briefly consider Mithen’s evolutionary psychology explanation for the origin of the human mind and art: it is attractive, but I believe that it has weaknesses and that it leaves some important points outstanding.

First, despite the considerable ingenuity of evolutionary psychologists, the explanation is heavily dependent on mental modules inferred, very largely, from animal and human behaviour. How can we be sure that pre-sapiens hominids had the four intelligence modules that Mithen postulates? To what extent are these modules inferred by modern human minds from modern human behaviour? Indeed, is it possible to infer modules from behaviour? Secondly, we have no direct information on the possible modularity of ancient minds. As a result, evolutionary psychologists are free to invent historical trajectories that move repeatedly between modularity and access between modules for as much as 100 million years.11 Thirdly, it is not clear how a species could break down the walls between chapels, at least in neurological terms. Would the creatures have to ‘grow’ new neural pathways, or would they simply have to learn to use ones they already had? Fourthly, the prominence of metaphors in Mithen’s discourse keeps us at a remove from the realities of human neurology, that is, from the matter of the mind. There is a tendency to develop the argument by exploring the metaphors rather than by coming to grips with realities. At times it is not clear whether the argument is being prosecuted entirely in a metaphorical realm. Technological innovations that involve non-invasive three-dimensional imaging of living brains are, however, beginning to test supposed connections between particular types of behaviour and specific brain locations.12

These four reservations are sources of concern, but they do not entirely eliminate the possibility that intelligence may indeed be modular in some way. Either way, we can proceed with our enquiry because I argue that we need to go beyond intelligence, whether it is modular or not.

My fifth reservation takes up this point. It concerns what I see as too exclusive an emphasis on intelligence. Intelligence is what researchers use when they study human origins and all the other puzzles of science. Whilst they allow intuition and unexplained flashes of insight a role in the solving of scientific problems, ideas so acquired must, they rightly insist, be subjected to rational evaluation.13 As a result of this essentially Western view, one that explains the invention of the radio and makes space travel possible, they regard rational intelligence, as they themselves experience it, as the defining characteristic of human beings. They therefore explain everything that early people achieved in terms of evolving intelligence and rationality – of becoming brighter and smarter. As they see it, early people were becoming more and more like Western scientists. This is what we may call ‘consciousness of rationality’.

Consciousness: neurological and social

The problem here is that the emphasis on intelligence has marginalized the importance of the full range of human consciousness in human behaviour. Art and the ability to comprehend it are more dependent on kinds of mental imagery and the ability to manipulate mental images than on intelligence. We must see consciousness as much more than the interaction of intelligence modules to create generalized intelligence. Mithen deals briefly with consciousness, but the way in which he does it is steeped in the general scientific emphasis on intelligence. Drawing on Nicholas Humphrey’ s14 work, he highlights ‘reflexive consciousness’. This phrase means not only being aware of our physical selves and our own thought (introspection), but also an ability derived from our social intelligence module: being able to predict the behaviour of others – in a sense, to read their minds. The adaptive value of this kind of consciousness is clear. But it is also clear that what is being described is part of highly valued Western problem-solving techniques.

What we have here is a case of our knowledge of the past being entrenched in present-day values and practices. In this instance, the social constructivist position (Chapter 2) clearly has some merit. What constitutes consciousness for us at our particular position in history informs our investigation and knowledge of the past. Catherine Lutz15 identifies a number of features that are considered integral to our own Western, twenty-first-century consciousness. These features include an absence of emotion in problem-solving, objectivity, linear thought, and sustained attention spans: ‘Consciousness so construed is seen as fundamentally good and important.’ 16 These features of consciousness as it is conceived in the West come out clearly in Lutz’s review of the historical definitions of consciousness listed in the Oxford English Dictionary.17 But when she moves on to consider consciousness as it is conceived in non-Western societies, the inadequacy of her method is exposed. She regards consciousness as something entirely constructed in social discourse and thus without neurological, ‘hard-wired’ foundations.18 In this, she (together with the many others who follow similar approaches) comes close to Descartes’s separation of mind from body. Despite her wish to rise above the received norms of her own Western society, she falls prey to a current academic aversion to any reference to the neurological basis of consciousness or behaviour. Other components of consciousness, such as Descartes’s dreams, are therefore considered aberrations and suppressed in formulations of what constitutes human consciousness. As we shall shortly see, consciousness is not entirely a construct. Rather, it derives from historically specific responses to and categorizations of a shifting neurological substrate.

For an initial illustration of this dialectic between social construction and neurological foundations I turn to the medieval concept of consciousness. It was different from present-day concepts, even though it had to make sense of the same neurological foundation. Medieval people valued dreams and visions as sources of knowledge vouchsafed by God. Hildegaard of Bingen (1098–1179), for example, believed that her visions revealed not just God’s personal instructions to her but also the material structure of the universe: she did not distinguish between religious revelation and ‘science’. Indeed, the contact with the deity that dreams and visions were believed to afford was considered a defining trait of human beings, a function of the divine spark that animals lacked, even if it was something to which not everyone aspired. Today this kind of mental state is generally shunned and is not considered a valuable component of human consciousness. No one in the West is likely to be elected to high political office on a ticket of a blinding, personal, divine revelation – or, for that matter, be consecrated as Archbishop of Canterbury. Yet the paradox remains: the large ‘esoteric’ sections of bookshops show that ‘non-scientific’ thinking is alive and well, and people still pray, meditate and consult priests and psychics. It is just that, today, altered states are marginalized in the conduct of affairs of state, scientific endeavour, and even within mainstream religion. What today constitutes acceptable human consciousness – the ‘consciousness of rationality’ – is therefore an historically situated notion constructed within a specific social context but founded on the neurology to which I now turn. It is not simply a function of interacting intelligences.

The spectrum of consciousness

I shall use a metaphor (inevitably!) to clarify aspects of the notion of consciousness. I hope that this metaphor will expose some serious lacunae in the ways in which archaeologists (and others) consider human consciousness and, more specifically, in what it was like to be human during the Transition. The contemporary Western emphasis on the supreme value of intelligence has tended to suppress certain forms of consciousness and to regard them as irrational, marginal, aberrant or even pathological and thereby to eliminate them from investigations of the deep past.

As long ago as 1902, the influential American psychologist William James, who successively taught physiology, psychology and philosophy at Harvard, noted that what we think of as normal, waking consciousness is only one type of consciousness (though, as we shall see, it too is not a unitary state), ‘whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness, entirely different’. He added: ‘No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded.’ 19 More recently, Colin Martindale, a cognitive (rather than evolutionary) psychologist, has re-emphasized the point that studies of the mind have concentrated too much on rational states. He argues:

We need to explore altered states of consciousness as well as normal, waking consciousness. We need to understand the ‘irrational’ thought of the poet as well as the rational thought of the [laboratory] subject solving a logical problem…. We need to investigate the historical evolution of ideas in the real world as well as how concepts are formed in laboratory situations. Finally, since people are not computers, we must ask how emotional and motivational factors affect cognition.20

Martindale is by no means alone in this view, yet archaeologists persist in ignoring all but the ‘consciousness of rationality’. The important point is that consciousness varies: we must not forget Descartes’s dreams and Hildegaard’s visions. Whether we ourselves value such experiences or not is irrelevant: they are an unavoidable part of being human, and, if we ignore their potential effects during the Transition and the Upper Palaeolithic itself, we must expect to produce no more than a partial explanation. I therefore suggest that we follow Martindale and think of consciousness not as a state but as a continuum or, the metaphor I favour, as a spectrum.

Two points about the colour spectrum are worth noting. First, in a spectrum cast by a prism on a sheet of white paper the colours grade imperceptibly into one another, yet there is no doubt that, say, red is different from green, and green is different from violet.

Secondly, we know that the Western notion that the colour spectrum comprises seven colours (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet) is not a given. Other cultures and languages designate and name different segments of the colour spectrum; that is, they divide up the spectrum differently. For instance, the Standard Welsh word glas denotes hues ranging from what in English is called green through blue to grey. By contrast, the Ibo word ojii denotes a range of hues from grey through brown to black. Why, then, do we think of the spectrum as comprising seven colours, when other cultures acknowledge fewer? It was Isaac Newton who decided on the seven colours. Having poor colour vision himself, Newton asked a friend to divide up the spectrum. When the friend obliged and split it into six colours, Newton insisted on seven colours because of the significance of the number seven in Renaissance thought, and, as Newton himself said, seven corresponded to ‘the seven intervals of our octave’. Newton therefore asked his friend to add indigo to the spectrum, it being a popular dye at that period.21

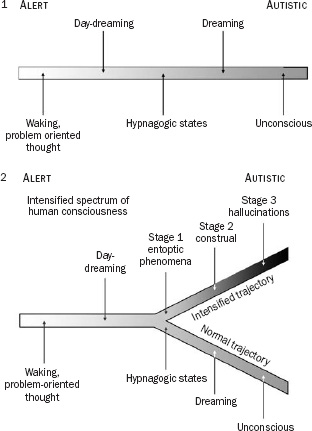

Bearing these two points in mind, I now introduce the spectrum of consciousness. I first describe the states that Martindale22 identifies between waking and sleeping. Thereafter, I consider a partly parallel trajectory and further states. According to Martindale’s view, as we drift into sleep we pass through:

– waking, problem-oriented thought,

– realistic fantasy,

– autistic fantasy,

– reverie,

– hypnagogic (falling asleep) states, and

– dreaming.

It should be noted that Martindale has imposed these six stages on a spectrum of states. Other researchers may find it useful to propose fewer or more stages.

In waking consciousness we are concerned with problem-solving, usually in response to environmental stimuli. When we become disengaged from those stimuli, different kinds of consciousness begin to take over. First, in realistic fantasy we are oriented to problem solving. We may, for instance, run through a possible social strategy that we plan to use in a forthcoming interview and assess possible outcomes. These realistic fantasies grade into more autistic ones, that is, ones that have less relevance to external reality. In what Martindale calls reverie, our thought is far less directed, and image follows image in no narrative sequence. Then reverie shades into hypnagogic states that occur as we fall asleep. Sometimes hypnagogic imagery is extraordinarily vivid, so vivid that people experience what are called hypnagogic hallucinations: they start awake and believe that their imagery of, say, someone entering the room was real. Hypnagogic hallucinations may be both visual and aural.23 Finally, in dreaming, a succession of images appears, at least in recall, as a narrative.24 Actually, we add much of the narrative structure as we recall the imagery. During REM sleep (rapid eye movement sleep that precedes deep sleep) random neuronal activity produces mental imagery. As we all know, this imagery is sometimes bizarre: images transmute into different ones, and we experience sensations of flying, fleeing, and falling, together with attendant emotions.

Concentrating on the first part of this sequence, the neuropsychologist Charles Laughlin and his colleagues25 speak of ‘fragmented consciousness’. They point out that during the course of a day we are repeatedly shifting from outward-directed to inward-directed states. Sometimes we are fully attentive to our environment; at other times we withdraw into contemplation and are less alert to our surroundings. This is simply an inherent feature of the way in which our nervous system functions. There is evidence that our normal waking day comprises cycles of 90 to 120 minutes of moving from outwarddirected attention to inward-directed states.26 As I have observed, 27 some societies regard inward-directed states as pathological, others see them as indicative of divine afflatus, while still others pay little attention to them.

Such is the spectrum of consciousness from shifting wakefulness to sleep. We must now consider another trajectory that passes through the same spectrum but with rather different effects (Fig. 25). I call it the ‘intensified trajectory’: it is more profoundly concerned with inward-direction and fantasy. Dream-like, autistic states may be induced by a wide variety of means other than normal drifting into sleep. One of these means is sensory deprivation, during which a reduction of external stimuli leads to the ‘release’ of internal imagery. Normal subjects, isolated in sound-proof, dark conditions report hallucinations after a few hours.28 They also experience what Martindale calls ‘stimulus hunger’: they crave and focus on even the smallest, most trivial stimulus. Comparable sensory deprivation is part of many Eastern meditative techniques. Devotees are required to shut out as much of their environment as possible and to concentrate on a single focal point that may be a repeated mantra or a visual symbol. Then, too, audio-driving, such as prolonged drumming, visual stimulations, such as continually flashing lights, and sustained rhythmic dancing, such as among Dervishes, have a similar effect on the nervous system. We also need to mention fatigue, pain, fasting and, of course, the ingestion of psychotropic substances as means of shifting consciousness along the intensified trajectory towards the release of inwardly generated imagery. Finally, there are pathological states, such as schizophrenia and temporal lobe epilepsy, that take consciousness along the intensified trajectory. Hallucinations may thus be deliberately sought, as in the ingestion of psychotropic substances, or they may be unsought, as in many of the other modes of induction that I have mentioned.

This second trajectory has much in common with the one that takes us daily into sleep and dreaming, but also differences. Dreaming gives everyone some idea of what hallucinations are like. For most modern Westerners, dreams lack the intensity of hallucinations, but earlier Western values (and those of many other societies) tended to take dreams seriously and to rescue them from the oblivion of forgetfulness.29 Perhaps one could say that the difference between the two spectra is a matter of degree rather than kind. I draw a distinction between the two trajectories because it is useful for the argument I am developing.

25 The two spectra of consciousness: (1) ‘normal consciousness’ that drifts from alert to somnolent states, and (2) the ‘intensified trajectory’ that leads to hallucinations.

The states towards the far end of the intensified trajectory – visions, and hallucinations that may occur in any of the five senses – are generally called ‘altered states of consciousness’. The phrase can apply equally to dreaming and ‘inward’ states on the normal trajectory, though some people prefer to restrict its use to extreme hallucinations and trance states. By now it will be obvious that this commonly encountered phrase is posited on the essentially Western concept of the ‘consciousness of rationality’. It implies that there is ‘ordinary consciousness’ that is considered genuine and good, and then perverted, or ‘altered’, states. But, as we have seen, all parts of the spectrum are equally ‘genuine’. The phrase ‘altered states of consciousness’ is useful enough, but we need to remember that it carries a lot of cultural baggage.

It is essential to note that all the mental states that I have described are generated by the neurology of the human nervous system; they are part and parcel of what it is to be fully human. They are ‘wired into’ the brain. At the same time, we must note that the mental imagery we experience in altered states is overwhelmingly (though, as we shall see, not entirely) derived from memory and is hence culturally specific.30 The visions and hallucinations of an Inuit person living in the Canadian snowfields will be different from the vivid intimations that Hildegaard of Bingen believed God sent to her. The Inuit will ‘see’ polar bears and seals that may speak to him or her; Hildegaard saw angels and strange creatures suggested by scripture and the medieval wall paintings and illuminations with which she was familiar. The spectrum of consciousness is ‘wired’, but its content is mostly cultural.

A neuropsychological model

The concept of consciousness that I have outlined will explain many specific features of Upper Palaeolithic art. In this, it is unlike other explanations (such as art-for-art’s-sake or information-processing) that provide overall, blanket understandings that could apply to virtually any images. But, if we are to attempt to cross the neurological bridge that leads back to the Upper Palaeolithic, we need to look more closely at the visual imagery of the intensified spectrum and see what kinds of percepts are experienced as one passes along it. We can identify three stages, each of which is characterized by particular kinds of imagery and experiences (Fig. 26).31

In the first and ‘lightest’ stage people may experience geometric visual percepts that include dots, grids, zigzags, nested catenary curves, and meandering lines.32 Because these percepts are ‘wired’ into the human nervous system, all people, no matter what their cultural background, have the potential to experience them.33 They flicker, scintillate, expand, contract, and combine with one another; the types are less rigid than this list suggests. Importantly, they are independent of an exterior light source. They can be experienced with the eyes closed or open; with open eyes, they are projected onto and partly obliterate visual perceptions of the environment. For instance, the so-called fortification illusion, a flickering curve with a jagged or castellated perimeter and a ‘black hole’ of invisibility in the centre, may, with a movement of the head, be positioned over a person standing nearby so that his or her head vanishes in the black hole (Chapter 5). This particular percept is associated with migraine attacks and is therefore well-known to sufferers from that condition. Such percepts cannot be consciously controlled; they seem to have a life of their own.34 Sometimes a bright light in the centre of the field of vision obscures all but peripheral images.35 The rate of change from one form to another seems to vary from one psychotropic substance to another36 but it is generally swift. Laboratory subjects new to the experience find it difficult to keep pace with the rapid flow of imagery, but, significantly for the understanding I develop in following chapters, training and familiarity with the experience increase their powers of observation and description.37

Writers have called these geometric percepts phosphenes, form constants and entoptic phenomena. I use entoptic phenomena because ‘entoptic’ means ‘within vision’ (from the Greek), that is, they may originate anywhere between the eye itself and the cortex of the brain. I take this comprehensive term to cover two classes of geometric percepts that appear to derive from different parts of the visual system. Phosphenes can be induced by physical stimulation, such as pressure on the eyeball, and are thus entophthalmic (‘within the eye’).38 Form constants, on the other hand, derive from the optic system, probably beyond the eyeball itself.39 I distinguish these two kinds of entoptic phenomena from hallucinations, the forms of which have no foundation in the actual structure of the optic system. Unlike phosphenes and form constants, hallucinations include iconic imagery of culturally controlled items, such as animals, as well as somatic (in the body), aural (hearing), gustatory (taste) and olfactory (smell) experiences.

The exact way in which entoptic phenomena are ‘wired into’ the human nervous system has been a topic of recent research. It has been found that the patterns of connections between the retina and the striate cortex (known as V1) and of neuronal circuits within the striate cortex determined their geometric form.40 Simply put, there is a spatial relationship between the retina and the visual cortex: points that are close together on the retina lead to the firing of comparably placed neurons in the cortex. When this process is reversed, as following the ingestion of psychotropic substances, the pattern in the cortex is perceived as a visual percept. In other words, people in this condition are seeing the structure of their own brains.

In Stage 2 of the intensified trajectory, subjects try to make sense of entoptic phenomena by elaborating them into iconic forms, 41 that is, into objects that are familiar to them from their daily life. In alert problem-solving consciousness, the brain receives a constant stream of sense impressions. A visual image reaching the brain is decoded (as, of course, are other sense impressions) by being matched against a store of experience. If a ‘fit’ can be effected, the image is ‘recognized’. In altered states of consciousness, the nervous system itself becomes a ‘sixth sense’ 42 that produces a variety of images including entoptic phenomena. The brain attempts to decode these forms as it does impressions supplied by the nervous system in an alert, outwardly-directed state. This process is linked to the disposition of the subject. For example, an ambiguous round shape may be ‘illusioned’ into an orange if the subject is hungry, a breast if he is in a state of heightened sexual drive, a cup of water if the subject is thirsty, or an anarchist’s bomb if the subject is fearful.43

26 The neuropsychological model. How the functioning of the human nervous system is shaped by the cultural circumstances of people experiencing altered states of consciousness.

As subjects move into Stage 3, marked changes in imagery occur.44 At this point, many people experience a swirling vortex or rotating tunnel that seems to surround them and to draw them into its depths.45 There is a progressive exclusion of information from the outside: the subject is becoming more and more autistic. The sides of the vortex are marked by a lattice of squares like television screens. The images on these ‘screens’ are the first spontaneously produced iconic hallucinations; they eventually overlie the vortex as entoptic phenomena give way to iconic hallucinations.46 The tunnel hallucination is also associated with near-death experiences.47

Sometimes a bright light in the centre of the field of vision creates this tunnel-like perspective. Subjects report ‘viewing much of their imagery in relation to a tunnel…[I]mages tend to pulsate, moving towards the centre of the tunnel or away from the bright light and sometimes in both directions.’ One laboratory subject said, ‘I’m moving through some kind of train tunnel. There are all sorts of lights and colours, mostly in the centre, far, far away, way, far away, and little people and stuff running around the [walls] of the tube, like little cartoon nebishes, they’re pretty close.’ Siegel found that among 58 reports of eight kinds of hallucinations, this sort of tunnel was the most common.48

Westerners use culture-specific words like ‘funnels, alleys, cones, vessels, pits [and] corridors’ to describe the vortex.49 In other cultures, it is often experienced as entering a hole in the ground. Shamans typically speak of reaching the spirit world via such a hole. The Inuit of Hudson Bay, for instance, describe a ‘road down through the earth’ that starts in the house where they perform their rituals. They also speak of a shaman passing through the sea: ‘He almost glides as if falling through a tube.’ 50 The Bella Coola of the American Northwest Coast believe such a hole is ‘situated between the doorway and the fireplace.’ 51 The Algonkians of Canada travel through layers of earth: ‘a hole leading into the bowels of the earth [is] the pathway of the spirits.’ 52 The Conibo of the Upper Amazon speak of following the roots of a tree down into the ground.53 Such reports could easily be multiplied. The vortex and the ways in which its imagery is perceived are clearly universal human experiences, and the descriptions of them that I have given will play a key role in subsequent chapters.

Stage 3 iconic images derive from memory and are often associated with powerful emotional experiences.54 Images change one into another.55 This shift in iconic imagery is also accompanied by an increase in vividness. Subjects stop using similes to describe their experiences and assert that the images are indeed what they appear to be. They ‘lose insight into the differences between literal and analogical meanings’.56 Nevertheless, even in this essentially iconic stage, entoptic phenomena may persist: iconic imagery may be projected against a background of geometric forms57 or entoptic phenomena may frame iconic imagery.58 By a process of fragmentation and integration, compound images are formed: for example, a man with zigzag legs. Finally, in this stage, subjects enter into and participate in their own imagery: they are part of a strange realm. They blend with both their geometric and their iconic imagery.59 It is in this final stage that people sometimes feel themselves to be turning into animals60 and undergoing other frightening or exalting transformations.

These three stages of the intensified spectrum of consciousness are not ineluctably sequential. Some subjects report being catapulted directly into the third stage, while others do not progress beyond the first. The three stages should be seen as cumulative rather than sequential.

Harnessing the brain

The implications of what I have so far said for an understanding of the Transition are clear and different from those implied by studies that concentrate on intelligence. All anatomically modern people of our own time and of the Transition have, or had, the same human nervous system. They therefore cannot, or could not,

– avoid experiencing the full spectrum of human consciousness,

– refrain from dreaming, or

– escape the potential to hallucinate.

Because the Homo sapiens populations of that period were fully human, we can confidently expect that their consciousness was as shifting and fragmented as ours, though the ways in which they regarded and valued the various states would have been largely culturally determined. Moreover, they were capable of passing along both the trajectories that I have described, though the content of their dream and autistic imagery would have been different. As we shall see, we cannot say exactly the same of the Neanderthals. We therefore have a neurological bridge to the Upper Palaeolithic, but probably not to the Middle Palaeolithic.

Furthermore, all societies are obliged to divide up the spectrum of consciousness into (probably) named sections, even as they divide up the colour spectrum in one way or another. Human communities are not viable without some (possibly contested) consensus on which states will be valued and which will be ignored or denigrated. Bluntly put, madness is culturally defined: what counts as insanity in one society may be valued in another. States that occasion embarrassment and are ignored in one society may be cultivated in another. But, despite such cultural specifics, the nervous system cannot be eliminated: all people experience dreaming on the first trajectory, and all have the potential to experience the states characteristic of the autistic trajectory. And they experience them in terms of their own culture and value system; this is what has been called the ‘domestication of trance’.61

The ubiquity of institutionalized altered states of consciousness is borne out by a survey of 488 societies included in Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas.62 Erika Bourguignon, who carried out this survey, found that an overwhelming 437, or 90 per cent, of these societies were reported to have ‘culturally patterned forms of altered states of consciousness’.63 She concluded that ‘the capacity to experience altered states of consciousness is a psychobiological capacity of the species, and thus universal, its utilization, institutionalization, and patterning are, indeed, features of cultures, and thus variable.’ 64 The materials from which the Ethnographic Atlas was compiled were, however, not always reliable, and the definition of altered states employed was too narrow. For example, sub-Saharan Africa is shown to have a comparatively high percentage of societies from which altered states are said to be absent. Yet we know that this is not the case. All sub-Saharan societies do recognize the importance of altered states, though they may not be as overtly institutionalized as in other parts of the world. Dreams, for instance, play a prominent role in these societies. It seems, then, that Bourguignon’s ‘capacity’ should be changed to ‘necessity’, if the full range of altered states is recognized and the ways in which they may be institutionalized are seen as highly variable.

Because there is no option but to come to terms with the full spectrum of consciousness, people of the Upper Palaeolithic must not only have experienced the full spectrum; they must also have divided it up in their own way and so created their own version of human consciousness.

This italicized paragraph encapsulates two vital steps in my argument. Although many Westerners today recognize the intensified trajectory for what it is and do not attach profound significance to its imagery, this ‘sceptical’ attitude is not, nor has been, universal.

For an instance of a non-Western attitude, I turn to the Tukano people of the Colombian northwest Amazon Basin and glance briefly at the stages of their yajé-induced visual experiences.65 Yajé is a psychotropic vine that occurs in numerous varieties. The Tukano speak of an initial stage in which ‘grid patterns, zigzag lines and undulating lines alternate with eye-shaped motifs, many-coloured concentric circles or endless chains of brilliant dots’ (Fig. 26).66 During this stage they watch ‘passively these innumerable scintillating patterns which seem to approach or retreat, or to change and recombine into a multitude of colourful panels’. The Tukano depict these forms on their houses and on bark and explicitly identify them as elements of their yajé visions. Geraldo Reichel-Dolmatoff, who worked for many years with the Tukano and other peoples of the Amazon Basin, demonstrated the parallels between what the Tukano see and draw and the entoptic forms established independently by laboratory research. Comparable but greatly elaborated and formalized designs come from ‘eye spirits’ to the Shipibo-Conibo shamans of eastern Peru during ayahuasca-induced hallucinations. These designs are believed to have therapeutic properties and to be closely associated with songs that are ‘engraved in the shaman’s consciousness’: song and design become one.67

In a second stage recognized by the Tukano there is a diminution of these patterns and the slow formation of larger images. They now perceive recognizable shapes of people, animals, and strange monsters. They see ‘yajé snakes’, the Master of the Animals who withholds animals or releases them to hunters, the Sun-Father, the Daughter of the Anaconda, and other mythical beings. The intense activity of this stage gives way to more placid visions in the final stage. It seems clear that the Tukano first and second stages correspond to our Stages 1 and 3 respectively.

Here, then, we have an instance in which people take hold of the possibilities of the intensified trajectory – they harness the human brain – and believe that they derive from their visions insights into an ‘alternative reality’ that, for them, may be more real than the world of daily life. This is a worldwide experience. Indeed, ecstatic experience is a part of all religions – as I have pointed out, people have to accommodate the full spectrum of consciousness in some way.

Amongst hunter-gatherer (and some other) communities the sort of experience that the Tukano describe is called ‘shamanism’. The word derives from the Tungus language of central Asia.68 Today this is a disputed word.69 Some researchers feel that the term has been used too generally to be of any use and that it should be restricted to the central Asian communities of its origin. Although I appreciate the point that these writers make, I and many others disagree. We believe that ‘shamanism’ usefully points to a human universal – the need to make sense of shifting consciousness – and the way in which this is accomplished, especially, but not always, among hunter-gatherers. The word need not obscure the diversity of worldwide shamanism any more than ‘Christianity’ obscures theological, ritual and social differences between the Russian Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic and the many Protestant Churches. Nor does ‘Christianity’ mask the changes that have taken place in those traditions over the last two millennia. Too intense a focus on differences is in danger of losing sight of the wood.

Because I use ‘shamanism’ frequently in subsequent chapters, I give a brief outline of what I take the word to mean when I use it to refer to ritual specialists in hunter-gatherer societies. Our ultimate goal is the Upper Palaeolithic when all people were hunter-gatherers, so we need not consider broader manifestations of shamanism, sometimes alongside and integrated with other religions.

– Hunter-gatherer shamanism is fundamentally posited on a range of institutionalized altered states of consciousness.

– The visual, aural and somatic experiences of those states give rise to perceptions of an alternative reality that is frequently tiered (hunter-gatherers believe in spiritual realms above and below the world of daily life).

– People with special powers and skills, the shamans, are believed to have access to this alternative reality.

– The behaviour of the human nervous system in certain altered states creates the illusion of dissociation from one’s body (less commonly understood in hunting and gathering shamanistic societies as possession by spirits).

Shamans use dissociation and other experiences of altered states of consciousness to achieve at least four ends. Shamans are believed to

– contact spirits and supernatural entities,

– heal the sick,

– control the movements and lives of animals, and

– change the weather.

These four functions of shamans, as well as their entrance into an altered state of consciousness, are believed to be facilitated by supernatural entities that include:

– variously conceived supernatural potency, or power, and

– animal-helpers and other categories of spirits that assist shamans and are associated with potency.

In listing these ten characteristics of hunter-gatherer shamanism I have excluded features that some writers consider important, if not essential, for the classification of a religion as shamanistic. I do not, for instance, link shamanism to mental illness of any sort, though some shamans may well suffer from epilepsy, schizophrenia, migraine and a range of other pathologies. Nor do I stipulate the number of religious practitioners that a shamanistic society may have; some societies have many, others very few. Some shamans wield political power, others do not. Nor do I stipulate any particular method or methods for the induction of altered states of consciousness. Still less do I attend to diverse concepts of the soul, spirit and subdivisions of the tiered cosmos.

In addition, I wish to emphasize the diversity of altered states of consciousness. If we focus, as some writers have done, too much on the word ‘trance’ and imagine ‘altered states’ to be restricted to deep, apparently unconscious conditions, we shall miss the fluidity of shamanistic experiences, and even fail altogether to notice the presence of altered states of consciousness in religious practices.70 The Saami shamans of Lapland and northern Scandinavia, for instance, receive visions and experience out-of-body travel in a variety of states. These range from a ‘light trance’ in which shamans are still aware of their surroundings but in which spirit helpers none the less appear and in which they can heal the sick and perform divinations. The spirits also appear to Saami shamans in ‘ordinary’ dreams. Then in ‘deep trance’, the shamans lie as if dead; in this condition, their souls are believed to have left their bodies and to have travelled to the spirit realm. In all three states, shamans are believed to have direct contact with the spirit realm. The anthropologist Anna-Leena Siikala took Arnold Ludwig’s study of altered states of consciousness as a starting point for her study of Siberian shamanism. She found that the socalled ‘ecstatic experience’ of shamans is far broader than is commonly imagined.71 These instances may be readily multiplied around the world. It is therefore essential to keep the full spectrum (or, as I have presented it, spectra) of consciousness in mind when we consider religious expressions that fall under the rubric of shamanism.

Just which stages of altered consciousness are emphasized and highly valued depends on the social context of an expression of shamanism. Some societies, such as the Tukano, place considerable value on Stage 1 entoptic phenomena; others virtually ignore Stage 1 and seek out Stage 3 hallucinations. In whichever stage, and also in hypnagogic hallucinations, shamans learn to increase the vividness of their mental imagery and to control its content. Novices learn to do this by ‘actively engaging and manipulating the visionary phenomena’.72 Allied to this engagement is ‘guided imagination’, a form of imagination that goes beyond what we normally understand by the word: in Siikala’s phrase, it consists in ‘setting aside the critical faculty and allowing emotions, fantasies and images to surface into awareness’. Amongst those ‘fantasies and images’ are beings and episodes from myths that the novice has been taught and that concern the ‘making’ of a shaman and the structure of the universe that he or she will traverse in spiritual travel; such images ‘are frequently used…as a means of achieving sensations and experiences of the other world’.73 The shamanistic mind is a complex interweaving of mental states, visions and emotions. We must beware of stipulating some naively simple altered state of consciousness as the shamanistic state of mind.

I am not alone in emphasizing the importance of making sense of altered states of consciousness in the genesis of religion. Peter Furst, then a research associate of the Harvard Botanical Museum, wrote, ‘It is at least possible, though certainly not provable, that the practice of shamanism…may have involved from the first – that is, the very beginnings of religion itself – the psychedelic potential of the natural environment.’ 74 Without stressing the use of psychotropic plants to alter consciousness, James McClenon sums up the matter: ‘[S]hamanism, the result of cultural adaptation to biologically based [altered states of consciousness], is the origin of all later religious forms.’ 75 And Weston La Barre came to the same conclusion: ‘[A]ll the dissociative “altered states of consciousness” – hallucination, trance, possession, vision, sensory deprivation, and especially the REM-state dream – apart from their cultural contexts and symbolic content, are essentially the same psychic states found everywhere among mankind; …shamanism or direct contact with the supernatural in these states…is the de facto source of all revelation, and ultimately of all religions.’ 76

Before we proceed to examine the evidence from Upper Palaeolithic western Europe in the light of what this chapter has set forth about the human brain/mind and the genesis of religion, I describe two shamanistic societies that made rock art – the San of southern Africa and the Native American groups of California. In both cases we have a considerable amount of information on their beliefs. We do not have to indulge in the blind (and often wild) guessing that is frequently associated with the study of rock art. These two case studies widen our understanding of how the working of the brain can be harnessed in hunting and gathering societies. They also present further key features of shamanism that are relevant to Upper Palaeolithic art.