Envoi

Perhaps it would be more correct to say that the end of Upper Palaeolithic cave art was but one episode in a much longer story.

Julian Jaynes, a Princeton psychologist, tried to pinpoint the time when people recognized hallucinations for what they are. In his book, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, 1 Jaynes identifies a change in narration between the Iliad and the Odyssey. In the Iliad, says Jaynes, the characters have no concept of free will. They have no conscious minds; they do not sit down and think things out. It is the gods who act, who tell men what to do. The gods initiated the quarrel among men, started the war that led to the destruction of Troy, and planned the campaigns. Thus Agamemnon claims that it was Zeus and the Erinyes, ‘who walk in darkness’, who caused him to seize Achilles’ mistress.2 These gods were inner voices that were heard as distinctly as present-day schizophrenics hear voices speaking to them, or Joan of Arc heard her voices. The gods, Jaynes concludes, were ‘organizations of the central nervous system…The god is part of the man…The gods are what we now call hallucinations.’ 3

According to Jaynes, the Odyssey followed the Iliad by as much as a century, and what a difference there is between the two epics. At centre stage now is wily Odysseus, not the gods. In the Odyssey, we are in a world of plotting and subterfuge. The gods have receded, and men take the initiative. This change, Jaynes argues, resulted from the breakdown of what he calls the bicameral mind. The human mind was no longer in two parts, one supplying the voices of the gods to the other. Now people could be in control of their thoughts and actions.

Yet it seems to me that Upper Palaeolithic people could attend to inner voices without, as Jaynes contends, being semi-automatons, unable to think for themselves. I therefore prefer to think in terms of primary and higherorder consciousness, the development of the second having taken place much earlier than the Iliad – at the emergence of Homo sapiens in Africa. Thereafter, it was culturally specific definitions of altered consciousness that determined whether people heeded their inner voices or not.

Emancipation of the mind from the imperative of voices and visions has in fact been a slow, stop-go-retreat process, one that is still incomplete.When and how did it become possible for people to stand back and contemplate their own thought processes, recognize that the voices they heard and the visions they saw came from within and not from external sources?

The controversial Yale literary critic Harold Bloom argues that it was Shakespeare who ‘invented’ the modern, Western, rational, independent human being. ‘The dominant Shakespearean characters – Falstaff, Hamlet, Rosalind, Iago, Lear, Macbeth, Cleopatra among them – are extraordinary instances…of how new modes of consciousness come into being.’ 4 Controversial he may be, but Bloom is surely right when he comments, ‘I find nothing in the plays or poems to suggest a consistent supernaturalism in their author, and more perhaps to intimate a pragmatic nihilism.’ Bloom agrees with A. D. Nuttall that Shakespeare ‘implicitly contested the transcendentalist conception of reality’.5 Shakespeare shows people changing, not as a result of being spoken to by gods, but by their interactions with other mortals and simply by ‘taking thought’, by an exercise of the individual human will. Hamlet argues with himself, not with gods or voices, as did the characters of the Iliad or, for that matter, Hildegaard of Bingen or Joan of Arc.

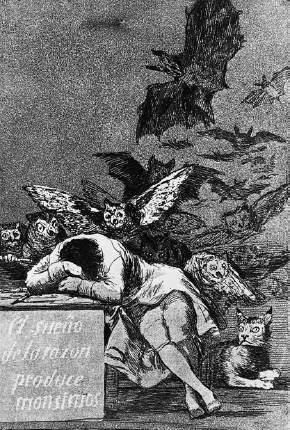

Many will feel that Bloom overstates his case when he claims that Shakespeare invented what we today accept as ‘human’, but he puts his finger on a key issue, on the independence of the human mind. After Shakespeare, it was the eighteenth-century Enlightenment that offered freedom from bondage, even though all Enlightenment thinkers did not take it. Today the Enlightenment receives an almost universally bad press. After two world wars and other horrors, bruised humanity feels it needs passion and commitment, not just reason. Reason, we are led to believe, is closely allied to positivism, intolerance and fascism. Yet there is no getting away from the conclusion that the Enlightenment opened up the possibility of knowing that the ‘voices’ came from within the human mind, not from powerful beings external to it. Optimistically, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant claimed: ‘Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his nonage.’ Enlightenment philosophers supplied a foundation for the emancipation that Shakespeare scented. Goya summed up that new philosophy in his engraving, ‘The sleep of reason brings forth monsters’ (Fig. 66). Behind the man slumped on the table rise terrifying, unsettlingly anthropomorphic bats, owls, cats and dark monsters.6

Yet, today, even after Darwin’s evolution-revolution and a string of breathtaking scientific advances, reason continues to doze, if not to sleep. New Age sentimentality exalts the ‘spiritual’ and retreats from reason. Bizarre sects control their adherents, even to mass suicide. Reports of out-of-body experiences, some in UFOs, are not uncommon. ‘Urban shamanism’ tries to resurrect a supposed primordial spirituality.Why should this be?

66 Goya’s engraving ‘The sleep of reason brings forth monsters’. Goya realized that his corrupt and violent society was ignoring the spirit of the Enlightenment. In his work he explored and proclaimed the dark extremities of the human mind.

Eugene d’Aquili, until his recent death Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, was one of a growing band of neurologists who are tackling these questions. ‘Neurotheology’ takes the mental features of shamanism that we have examined and tries to find out more about them and, further, the neurology of all religions. As a starting point, d’Aquili put a twist on Lévi-Strauss’s ideas and argued that myths are structured in terms of a major binary opposition, one polarity being humankind, the other some supernatural force.7 It is the supernatural force that gives human beings the power to appear to resolve other, more specific, polarities posed by each particular myth, which may be life:death, good:evil, health:sickness, or some other imponderable. In doing so, myths appear to explain the workings of the cosmos and catastrophic events.

Allied to the resolution of such irresolvable oppositions is mystical experience, transcendence, or ‘Absolute Unitary Being’, the sense of being overwhelmed by ineffability and thereby achieving insights into the ‘mystery’ of life but without, necessarily, contact with spirit beings. As Wordsworth memorably expressed it, the ‘affections gently lead us on,

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

An explanation for this sense of Absolute Unitary Being – and for the other mystical experiences that we have tracked through the Upper Palaeolithic and that are still reported today – seems to lie in the human nervous system.8 Neurobiologists are exploring what happens in the brain when people are overcome by ineffable feelings that they ascribe to divine visitation or an aesthetic oneness with the universe – what are, in effect, altered states of consciousness.9

The explanatory and emotional components of religion led these researchers to focus on two neurobiological processes. The first of these is what they call the ‘causal operator’, that is, ‘the anterior convexity of the frontal lobe, the inferior parietal lobe, and their reciprocal interconnections’. I need not now explain these neurological terms save to say that they are parts of the brain and that the researchers argue that they and their interconnections automatically generate concepts of gods, powers and spirits; these ‘supernatural’ entities are implicated in attempts to control the environment. This ‘pragmatic’ component of religion is intimately linked to the second component – emotional states and altered states of consciousness that, for participants, verify the existence of spiritual entities that cause things to happen. The sense of Absolute Unitary Being – transcendence, ecstasy – is generated by ‘spillover’ between neural circuits in the brain, which is, in turn, caused by factors we have considered in this book – visual, auditory or tactile rhythmic driving, meditation, olfactory stimulation, fasting, and so forth. The essential elements of religion are thus wired into the brain. Cultural contexts may advance or diminish their effect, but they are always there. This, in d’Aquili and Andrew Newberg’s provocative phrase, is why God won’t go away.

If these neurobiologists are correct, and they have a persuasive case, the fundamental dichotomy in human behaviour and experience that I noted in the Preface – rational and non-rational beliefs and actions – will not go away in the foreseeable future. A prisoner who escapes from Socrates’s cave encounters disbelief on his return. We are still a species in transition. But the neurology of mystical experiences and their persistence from the Upper Palaeolithic to the present, like the demise of Upper Palaeolithic art itself, are topics that lie beyond the scope of this book.

And yet…Who would wish to deny the wonder of Upper Palaeolithic art, Wordsworth’s seeing ‘into the life of things’, the great music that religious devotion (and a good deal of cerebral activity as well) inspired in Bach, John Donne’s wrestling with the ineffable, or a Miserere in the soaring acoustic of King’s College chapel? If we dismiss such things as merely the functioning of the brain, are we in danger of losing something supremely valuable? Perhaps we should distinguish between, on the one hand, Wordsworth’s pantheism and Donne’s intellectual devotion and, on the other, the terrible belief that God is speaking directly to us and telling us not only how to order our own lives but also to impose that order on others’ lives. What is in our heads is in our heads, not located beyond us. That is the crux of the matter, and it does not diminish Bach, Shakespeare, Donne and Wordsworth.

But the exaltation that those great creators excite in us does not justify mystical atavism. Shamanism and visions of a bizarre spirit realm may have worked in hunter-gatherer communities and even have produced great art; it does not follow that they will work in the present-day world or that we should today believe in personal spirit animal guides and subterranean worlds. We can catch our breath when we walk into the Hall of the Bulls without wishing to recapture and submit to the religious beliefs and regimen that produced them.