MINDSCAPES OF THE POSTGLACIAL EPOCH

[T]he [urban] revolution seems to mark,

not the dawn of a new era of accelerated advance,

but the culmination and arrest of

an earlier period of growth.

THE UPPER PALEOLITHIC was a time of more or less steady innovation and growth of knowledge. Although the uncertainties of discovery and dating in this range make it difficult to identify intervals when the pace of innovation may have slowed or halted altogether, the archaeological record yields a long succession of novelties from fur hoods to fishhooks and boats to baking ovens. The cumulative effect of these inventions was to redesign humans in a variety of ways, in accordance with the collective mind. Their practical impact from a biological standpoint was to allow one species—of recent tropical origin—to colonize most terrestrial habitats on the planet and to expand the size and density of some populations.

The development of the super-brain, which multiplied and spread with modern human foraging groups, also had brought forth a new phenomenon that operated above the level of the brain of an individual organism. The evolution of language and other forms of symbolic communication had allowed the members of each group to integrate their brains, significantly increasing the computational and recursive power of human thought. Moreover, by communicating thought from one generation to the next through oral tradition and artifacts, the collective mind had escaped the narrow confines of biological time and acquired a potentially unlimited “life span” of its own. Each collective mind had accumulated knowledge over the course of many Upper Paleolithic generations.

The growth in population and settlement size was a consequence of the redesigned human, who controlled an increasingly large and diverse supply of food and energy through technology. In the later Upper Paleolithic, modern humans in several parts of the world began to move away from their ancient mammalian foraging ecology to a sedentary economy based on domesticated plants and animals. The super-brain created an alternative ecological niche for the human organism—a niche subject to continual change and expansion that allowed for potentially unlimited growth. And with the emergence of large populations and sedentary communities, humans began to redesign the landscape as well as themselves.

During the Upper Paleolithic, efforts to refashion the landscape had been largely confined to the microhabitat represented by an artificial shelter or a house or by a corral or fish weir.1 The domestication of dogs may be regarded as a modest and unintentional move to reshape a small piece of the biotic environment. But with the appearance of farming villages and the eventual spread of towns and cities, people began to transform meadows into crop rows and streams into linear canals. They constructed rectangular buildings, laid out orthogonal street grids, and designed geometrically complex plazas and palaces. These created landscapes had no precedent on Earth; they reflected neither the processes of geomorphology nor the evolved patterns of organic life, but the peculiar forms of the mind.2

As local populations grew to massive size—to thousands of individuals—people began to redesign their societies in equally strange ways. Forms generated in the collective mind were imposed on the evolved organic patterns of age, gender, and biological kinship. People came to be classified in accordance with created social and economic roles, such as stonecutter, potter, blacksmith, accountant, priest, slave, and king. This hierarchical specialization of thought and action apparently was essential to the functioning of the civilizations that arose from towns and cities in the Near East, China, Mexico, and other places in the postglacial epoch.

Although hierarchical social organization seems to have developed, at least in some places, without violence or armed coercion, warfare inevitably accompanied the early civilizations. More often than not, they faced real or perceived external threats that required a specialized hierarchy in the form of an army. Most early civilizations eventually expanded by forcibly incorporating cities and towns into a larger political entity. As a consequence, they also faced internal threats—uprisings, civil war, and disintegration into smaller units. Under these conditions, novel ideas and alternative realities often were categorized as dangerous and subversive, and the creative powers of the mind were suppressed.

The pace of technological innovation slowed in most early civilizations and sometimes ceased altogether, even though the total number of brains integrated into the collective mind of each state had increased exponentially. Moreover, many brains were devoted to specialized areas of thought and activity, and new means for their integration in both space and time had been created, especially writing. For reasons that remain obscure, western Europe broke out of the pattern of stasis after 1200, and the result was the modern world—in terms of both the advance of technology and the construction of reality.

The Civilized Mind

Ideology emerges with the state: a body of thought to complement a political entity.

After more than seventy-five years of research and debate, the social and economic revolutions in human prehistory conceived by V. Gordon Childe remain key concepts in archaeology.3 The first of them—the development of sedentary farming communities during the Neolithic—now seems less of a revolution and more of a gradual development from mobile foraging to controlled harvesting of plants and animals through cumulative technological creativity. The roots of the Neolithic extend back 20,000 years to the Last Glacial Maximum, if not earlier. The Urban Revolution—the birth of civilization—though, retains its explosive character.

Lewis Mumford labeled the early civilizations mega-machines and likened them to massive mechanical devices “composed solely of human parts.”4 They were, in many respects, experiments in social technology that reflected an inability to understand, or perhaps an unwillingness to acknowledge, the properties of the raw materials from which they were constructed. Many of the human parts of the machine probably were unhappy with their roles. Above all, civilization reflected the trauma of forcing nation-state organization onto a social order that was still defined primarily by family relationships.5 Ideology was substituted for blood ties and marriage alliances. Inevitably, perhaps, the governments of the newly formed civilizations identified themselves with the forces that control the universe.

Civilization seems to represent a threshold in the density of the population or the size of the super-brain, at which the latter undergoes reorganization. There are, it would appear, simply too many individual brains and voices and insufficient communication and integration among them.6 The size of the threshold is not entirely clear, but it numbers in the thousands at a minimum. Each of the cities that were hammered together to form a state in ancient China probably had several thousand inhabitants, and similar numbers are estimated for the urban centers that became the Maya civilization. But some of the latter, as well as some of the Sumerian cities that became city-states before being consolidated into a wider political organization, seem to have been larger.7 And some sedentary societies that never morphed into nation-states, even though exhibiting elements of hierarchical organization, comprised many thousands of people.8

The reorganized super-brain became the nation-state. It exhibited a predictable hierarchical structure, with centralized political authority and a large organization of administrative assistants, priests, technicians, workers, and slaves, whose roles and relationships were at least partly defined by ideology. According to the Egyptologist Barry Kemp: “Fundamental to the state is an idealized image of itself, an ideology, a unique identity. It sets itself goals and pursues them by projecting irresistible images of power. These aide the mobilization of the resources and energies of the people, characteristically achieved by bureaucracy. We can speak of it as an organism because although made by man it takes on a life of its own.”9 The early civilizations also exhibited a pattern of specialization in thought and activity among their individual components. Even the simplest state organization contained craft specialists, such as potters, metallurgists, engineers, and scribes.

In order to function as an integrated whole, the national mind generated systems of writing, along with systems of weights and measures and of coinage. These were newly created internal components of the reorganized super-brain, analogous to spoken language and visual art in Upper Paleolithic times.10 The earlier forms of communication and record keeping were apparently insufficient to integrate and manage such large organizations. Civilizations have continued to develop new means of management and integration, such as clocks, newspapers, radio, and the Internet.

Monumental architecture in the form of public buildings and plazas was another seemingly inevitable manifestation of civilization. Although typically regarded as the primary technical achievement of the early nation-states, the massive public structures also were a form of communication analogous to art and language in many ways. They were powerful symbols of the political and religious ideology of the state. And they were typically used as the setting for major public ceremonies or rituals.11

The social hierarchy of the early civilizations is so similar to that of the eusocial insects, especially the ants, that many of the same categories, such as worker and soldier, can be applied to both types of societies. The reorganized super-brain that represents the nation-state exhibits closer parallels to the super-organism than did its Upper Paleolithic and Neolithic predecessors. A fundamental difference remains, however, between the two entities. Ant societies build massive complexes of chambers and passageways, but they have no need for monumental architecture and public rituals. Such efforts would be a waste of time, energy, and resources. The reproductive biology of the eusocial insects has allowed them to generate state-like organization within the context of the family, so there is no conflict between king and clan.12

The slowing pace of innovation in the early civilizations—especially after what seems to have been an extraordinary surge of invention in the period leading up to, and perhaps immediately following, the formation of these societies—suggests that the newly reorganized super-brain was not very creative. The perceived lack of innovation in nation-states before the end of the Middle Ages in Europe has been a recurrent topic of debate among historians of technology.13 After what Robert McC. Adams described as “a brief creative burst” and “extraordinary technological advances” associated with the rise of urban centers, inventions almost completely ceased in the ancient Near East.14 The pattern is less evident during late antiquity in Hellenistic Greece and imperial Rome, and especially in China (before the Ming dynasty), but even in these settings there is a contrast with developments in western Europe after 1250.15

Both the organization and the ideology of the early nation-states probably discouraged novel thinking. Self-appointed governments are threatened by alternative realities, and the creative powers of individual brains would have been a potential source of instability in these hierarchical systems.16 Moreover, the people at the top of these newly formed hierarchies had acquired the means to suppress alternative thinking—at least when externalized by speech or action—through the apparatus of the state. And they promoted the notion that they were connected to the controlling forces of the universe, either representing the divine or at least possessing special abilities (applied astronomy or other methods of divination) to interpret the direction of those forces correctly.

A major consequence of civilization was a slowing—and, in some cases, even an arresting—of the growth of the collective mind with respect to the accumulation of knowledge and the increased ability to manipulate the external world. The growth of the mind is dependent on creativity and novelty—applied to both technology and explanation. The narrow hierarchical structure of the early nation-states seems to have discouraged or suppressed much of it because the increased potential for creativity represented by a larger and more diverse population was more of a threat than an asset. The reorganized super-brain represented by the early civilizations was less capable of generating alternative realities than were its predecessors, and, for the most part, reality was stabilized for several thousand years.

An Alternative Landscape

[H]umans have been engaged in creating a living and working place, a human-built world, ever since their ouster from the Garden of Eden.

The Near East is the region where both sedentary farming communities and early civilizations first developed. The consensus among archaeologists is that the reason lies in its high biological productivity—enhanced by changing weather patterns at the end of the glacial epoch—and its mosaic of diverse local habitats, which supported a number of potential plant and animal domesticates. As Upper Paleolithic foraging groups expanded their control over this rich environment 20,000 to 15,000 years ago, their numbers increased with particular vigor.

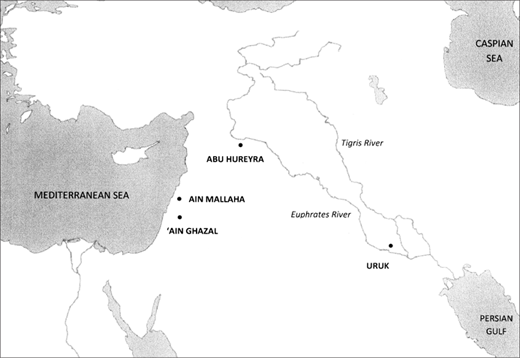

The well-known Fertile Crescent—which stretches from the Jordan Valley north and east across Anatolia and then bends southeast toward the Persian Gulf (figure 5.1)—supported open woodland and grassland inhabited by various wild cereals (wheat, barley, and rye) and legumes (beans, peas, and lentils). Wild sheep and goats dwelt in the uplands. As today, there was significant altitudinal variation in local environments. After 17,000 years ago, temperature and moisture began to rise.17

The broad-based high-tech foraging economy that long preceded the farming villages of the Fertile Crescent is illustrated by an Upper Paleolithic settlement on the Sea of Galilee. Ohalo II (Israel) was occupied immediately after the peak cold and aridity of the Last Glacial Maximum, roughly 20,000 years ago. An unusual drop in water level two decades ago exposed traces of brush huts with stone flooring and other remains that had been exceptionally well preserved in the waterlogged sediment. Plant foods consumed at the site included more than thirty species, among which were wild emmer wheat and barley. Other plants apparently were used for medicinal purposes. Gazelles, birds, fish, and mollusks were represented among the animals. Technologies for preparing food included mortars, pestles, and an arrangement of stones that may have been a simple baking oven.18

Figure 5.1 Map of the Fertile Crescent region, showing the location of sites mentioned in the text.

People in the region continued to pursue a mobile foraging economy as the climate became warmer and wetter after 17,000 years ago. During this phase, groups expanded into areas of former desert. After 14,000 years ago, more stable settlements appeared. They include sites assigned to the Natufian culture, such as Ain Mallaha (Israel) and contemporaneous occupations at sites like Abu Hureyra (Syria). Many Natufian settlements are substantially larger than earlier sites and contain traces of circular semi-subterranean dwellings with stone foundations. The process of innovation continued, as Ofer Bar-Yosef observed: “The technological innovations introduced by the Natufians, such as sickles, picks, and improved tools for archery, were added to an already existing Upper Paleolithic inventory of utensils that included simple bows, corded fibers, and food processing tools such as mortars and pestles.”19 Although storage facilities are not especially common—Ain Mallaha contains some likely examples—burials are quite numerous in comparison with those of the preceding era, suggesting a more sedentary lifestyle. Also indicative of sedentism are household trash heaps containing the remains of mice.20

It appears that settled communities preceded, and in some respects triggered, agriculture, and not the reverse. Traces of domesticated plants do not show up in the Levant until after a sedentary economy was already in place. The cooler and drier climates of the Younger Dryas period (roughly 12,800 to 11,300 years ago) may have provided the catalyst. The expanding Natufian population probably experienced severe stress as the resource base contracted during this period. The cultivation of cereals like einkorn and rye seems to have been a response, and there is evidence for small-scale agriculture at sites on the margin of the retreating forest zone like Abu Hureyra. As conditions worsened, Abu Hureyra was abandoned altogether. It was reoccupied, however, at the end of the Younger Dryas by a larger community—a true farming village.21

Experimental research indicates that the process of domestication—altering the genetic structure of plants and animals through artificial selection—could have taken place in twenty to thirty years with some wild cereal species.22 The intensification of harvesting and replanting as conditions deteriorated during the Younger Dryas may have accelerated the selection of desired phenotypes. Instead of adapting themselves to a changing environment, villagers at the western end of the Fertile Crescent were redesigning the environment—creating an alternative landscape. The consequences of domestication for human population biology were immense because the altered landscape could support more people per unit area. A larger population density would provide both the need and the means for further alterations; potential growth would be limited only by the total resources of the planet.

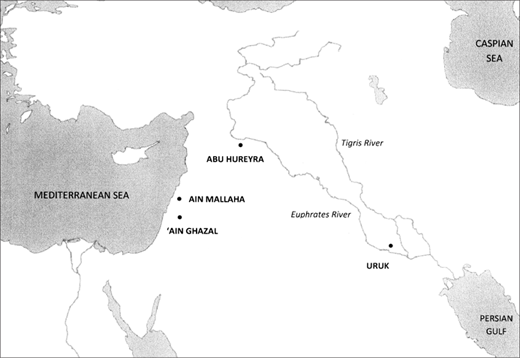

By 9,000 years ago, agricultural settlements like ‘Ain Ghazal (Jordan) occupied more than 25 acres and contained multiroom and even multistory houses (figure 5.2). The dwellings exhibit a shift from the earlier circular form to the rectilinear shape that continues to dominate the mindscape. Grain-storage facilities and public structures—shrines and, eventually, temples—also were present in these sites. The population of ‘Ain Ghazal is estimated at 2,500 to 3,000 people by 8,000 years ago. Both the domestication of sheep and goats and the production of pottery took place at this time.23

Figure 5.2 The settlement of ‘Ain Ghazal (Jordan) occupied more than 25 acres by 9,000 years ago, comprising multiroom and multistory houses. (Drawn by Ian T. Hoffecker from a photograph by Y. Zo’bi)

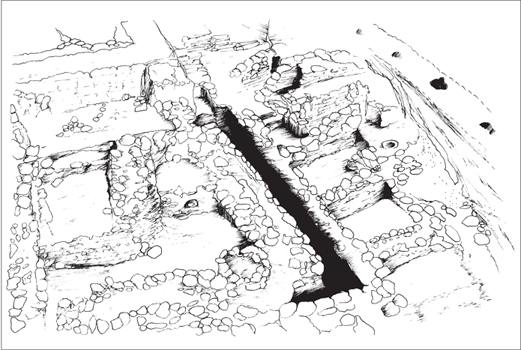

At this point, if not before, farmers colonized the eastern terminus of the Fertile Crescent, establishing villages in southern Mesopotamia. Although drier than the Levant, the alluvial lowlands near the Persian Gulf are especially suited to irrigation due to the configuration of natural watercourses and the overall topographic setting. Between 7,800 and 5,800 years ago, the local population constructed and managed a growing network of irrigation canals. As the area of irrigated cropland expanded, the population and villages grew in size. Large-scale irrigation was another important step in redesigning the environment that had substantial consequences for the human population. It entailed significant alterations to the physical landscape, not simply to its plant and animal inhabitants, and expanded human knowledge in a new realm: hydrology and water engineering. Moreover, the larger canals eventually acquired another highly important function—facilitating transport and trade among the growing network of communities in the Mesopotamian alluvium (figure 5.3).24

The world’s first cities emerged from the rapidly growing population centers of the Fertile Crescent. The rate of growth was exponential. The town of Uruk on the Euphrates River in modern Iraq occupied an estimated 175 acres by 5,800 years ago. It was more than five times the size that ‘Ain Ghazal had been roughly 2,000 years earlier. Within 600 to 800 years, Uruk had grown to approximately 620 acres and contained a population estimated at between 25,000 and 50,000. By 4,900 to 4,800 years ago, the city had exploded in size to almost 1,480 acres.25 The interactions within and among the growing cities of southern Mesopotamia—not only trade and alliance, but also competition and military conflict—became increasingly intense. Uruk and other cities were surrounded by defensive walls.

Figure 5.3 Landscape of the mind: as the size of the super-brain increased, internal connections—analogous to those of the neocortex in an individual brain—developed in the form of roadway and canal systems in southern Mesopotamia. Ur III-Isin-Larsa–period settlement patterns are shown here. (From Robert McC. Adams, Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981], 162, fig. 31)

By 5,100 years ago (3100 B.C.E.), the cities had organized themselves into a social and economic hierarchy: the civilization of Sumer.26 As during the earlier transition from a foraging to an agricultural economy, population stress induced by climate change may have been a catalyst. Drier climates prevailed after 5,800 years ago, and conditions became even cooler and drier around 5,200 to 5,100 years ago. A decline in food production and the abandonment of the most arid areas is widely thought to have created a mass of refugees and a potential pool of cheap dependent labor.27 At the same time, the organizational demands of an increasingly complex society and economy seem to have spawned a class of administrators and record keepers, while armies demanded commanders and foot soldiers. And at the bottom of the hierarchy were a growing number of slaves, generated by military conquest.28

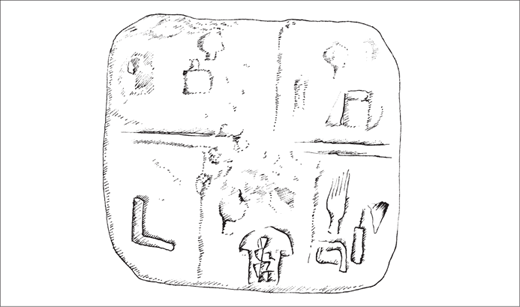

Major technological innovations accompanied the emergence of Sumerian civilization. The most notable were writing and mathematics, which seem to have evolved from the digital notational systems of the Upper Paleolithic. A significant breakthrough—analogous to Gutenberg’s invention of movable type—was the development of numerical notation tablets around 5,400 to 5,300 years ago. Pictographic writing appears in southern Mesopotamian sites 5,200 to 5,100 years ago (figure 5.4).29 Analysis of written texts reveals that the new information technology was used primarily for accounting and record keeping.

Writing and numerical systems seem to be essential to the nation-state, which is simply too large and complex to function without them, and therefore critical to the reorganization of the super-brain that coincided with their development. More broadly, writing and mathematics altered the collective mind in a fundamental way. The simple notational systems of the Upper Paleolithic represented an externalization of brain function on a very small scale. With the invention and widespread application of writing, a rapidly expanding corpus of memory was moved outside individual brains and into various technological forms of storage. Most of human memory now resides in these external components of the super-brain.

Figure 5.4 The hand was finally employed to create symbols in digital form, as does the vocal tract, with the invention of writing and mathematics, as illustrated by a Sumerian pictograph tablet from the settlement of Kish, dating to more than 5,000 years ago. (Drawn by Ian T. Hoffecker, from a photograph in Glyn Daniel, The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of Their Origins [New York: Crowell, 1968], 51, fig. 4)

By externalizing memory and creating a system of visual–linguistic feedback—analogous to the sensory feedback of artifact manufacture that began in the Lower Paleolithic—writing altered the process of thinking. The growing archive of memory and thought came to be accessible across increasingly large expanses of space and time. The super-brain had existed outside the lives of individuals in oral tradition and the corpus of information stored in artifacts (primarily in analogical form). Now it assumed a significantly greater presence as external representations were stored and manipulated in digital form. And as people began to discover the properties of numbers and apply them to calculations rather than simple counting, mathematics also changed the process of thinking.

The adoption of domesticated animals for agriculture and transportation was a major technological advance that preceded and probably accelerated the rise of cities and nation-states. Domesticated oxen were used to pull plows, ultimately derived from the Upper Paleolithic digging stick, for crop production, while domesticated donkeys were employed as pack animals. Both innovations were in place before 5,000 years ago. They represented the first use of an energy source other than human muscle power. Donkeys are credited with intensifying interaction among the Mesopotamian cities by facilitating trade and communication. Another harnessed source of energy probably was wind power: there is evidence for the presence of sail boats that—along with barges hauled by people or oxen—were used to move large quantities of goods along the network of waterways.30

The Sumerians traditionally are credited, of course, with the invention of the wheel. The key innovation actually is the wheeled vehicle, which is relatively complicated and was subject to many later refinements, such as the revolving front axle.31 Wheels were shaped from solid wood and attached to heavy four-wheeled wagons, usually drawn by oxen, as well as two-wheeled carts. Powered vehicles are tied to the expanding trade and communication networks among cities and towns, but they also had military applications. Like the Upper Paleolithic bow, wheeled vehicles were not modeled on or inspired by any observable natural phenomena. They were an ingenious creation of the mind that yielded almost immediate and highly practical benefits.32

Both raw materials and artifacts became commodities in Sumer, and written texts document the production and transport of a variety of items. This development was related to a fundamental change in the way people made things, which reflected the hierarchical social and economic structure. Between 8,000 and 7,000 years ago, Mesopotamian pottery vessels became increasingly standardized: “mass-produced” on revolving pottery wheels.33 Textiles also were woven on a titanic scale by 5,000 years ago in Uruk and other major cities. Thousands of workers, typically dependent women and children, manufactured woolen textiles in state-owned workshops reminiscent of a Charles Dickens novel. Cloth was woven on horizontal and vertical looms and then treated with an alkaline solution in large vats.34

For many archaeologists and historians, monumental architecture represents the most impressive technical achievement of the early civilizations. This view may be influenced by the psychological effect that these structures still possess, despite their weathered familiarity and the long absence of the formidable political entities they once symbolized.35 The shrines that had been constructed in south Mesopotamian villages were expanded into large temple complexes—often associated with staged towers, or ziggurats—in Sumerian cities. A major temple in the city of Ur was described by Samuel Noah Kramer:

[It] consisted of an enclosure measuring about 400 × 200 yards which contained the ziggurat as well as a large number of shrines, storehouses, magazines, courtyards, and dwelling places for the temple personnel. The ziggurat, the outstanding feature, was a rectangular tower whose base was some 200 feet in length and 150 feet in width; its original height was about 70 feet. The whole was a solid mass of brickwork with a cover of crude mud bricks and an outer layer of burnt bricks set in bitumen. It rose in three irregular stages and was approached by three stairways consisting of a hundred steps each.36

The temple complexes were the locus of regularly scheduled public ceremonies.

Although the Sumerian temples and ziggurats were the first known monumental buildings, it was the Old Kingdom of Egypt that designed and built the most awesome structures among the early civilizations—in terms of both scale and precision. The Great Pyramid at Giza, which was constructed during the reign of Cheops in the Fourth Dynasty (2600–2450 B.C.E.), is the supreme example. Assembled from roughly 2.3 million stone blocks (averaging 2.5 tons apiece), the base rests on a nearly perfectly level platform that occupies 13.1 acres. Each side originally measured between 755.43 and 756.08 feet in length (that is, varying by no more than 7.9 inches, or 0.01 percent). The four corners were almost perfect right angles (less than 1° deviation), and the entire structure was aligned almost exactly with true north.37

The Great Pyramid and other monumental buildings of the ancient civilizations were an early example of the application of mathematics to technology. The Sumerian irrigation systems—reportedly laid out with the help of levels and measuring rods—were another. The applications extended beyond simple arithmetic to geometry. It was a profound development with far-reaching consequences—virtually all of modern industrial technology is produced with mathematical applications—and a defining difference with earlier technology. In part, it reflected practical requirements imposed by the scale of monumental structures and other public works such as roads and canals. The parallel applications of writing and arithmetic to record keeping and accounting addressed analogous requirements of scale in the national economy. They also reflected a more precise rendering of the mindscape.

Mathematics was applied to time as well as space, and it represented a new way of perceiving and interpreting the universe. All the early civilizations designed long-term calendars, which organized time hierarchically into numerical units. The Sumerian calendar subdivided the year into twelve lunar months and required the periodic insertion of an intercalary month to adjust for the imprecise synchronization of the solar and lunar cycles. The day was subdivided into hours, which could be measured with a water clock. The Egyptians developed several unsynchronized calendars that covered annual cycles of flooding of the Nile River, as well as lunar and stellar cycles, but they also devised a civil calendar of twelve 30-day months and 5 extra days, for a total of 365 days. The day was subdivided into twenty-four hours, but the length of the hours varied according to season.38

Agriculture and nation-states emerged in several other parts of the world after the appearance of Sumerian civilization 5,100 years ago. Each civilization was unique and reflected both local environmental conditions and historical factors, but all of them exhibited a general pattern of hierarchical social organization and economic specialization—as well as new information technologies for the integration and management of its components—that may be explained as a common response to very large densities of people.

Egyptian civilization materialized shortly after the appearance of the Sumerian state, but as the result of a somewhat different process. The autonomous city-states of southern Mesopotamia never developed in the Nile Valley, and political integration was achieved through military unification of the northern and southern regions: Lower and Upper Egypt, respectively. The notion of the kingdom as “two lands” remained ever after. Egyptian civilization nevertheless produced most of the features found in Sumer.39

A nation-state did not arise in China until roughly 4,000 years ago: a full millennium after the appearance of Sumer. The roots of sedentary settlement and farming in East Asia are deep, however, extending back to the making of pottery and harvesting of potential plant domesticates in the aftermath of the Last Glacial Maximum. Settled communities based partly on agriculture and similar to those in the Near East about 9,000 years ago were present in northern China by 8,000 years ago. During the next few millennia, the population continued to grow, and by 4,000 years ago northern China was filled with walled towns, each inhabited by several thousand people under the control of a local clan. Many of them were brought under the aegis of the first ruling dynasty (Xia) to create a nation-state. It exhibited most of the features of Sumerian and Egyptian civilization—with the notable exception of monumental architecture, which was present but in subdued form.40

Civilization arose much later in the Americas. One reason for the delay may have been the absence of a lengthy development of a broad-based high-tech economy during the later Upper Paleolithic that produced semi-sedentary settlements before the beginning of the postglacial epoch. Such a pattern of development is now evident in both the Near East (including the Nile Valley) and China. Modern humans do not seem to have reached the Western Hemisphere until relatively late (about 15,000 years ago), and the American contemporaries of the Natufians appear to have been mobile foragers with a relatively simple technology. Farming villages were present in parts of Central America by 3,800 years ago, and complex societies with elaborate tombs and monumental art emerged a few centuries later.41

Civilization on a scale commensurate with that in Egypt or China did not appear in Mesoamerica until 2,300 years ago with the late Preclassic Maya, who developed writing, monumental architecture, and a calendar. The Maya comprised a large and dense population; the city of Tik’al is thought to have been inhabited by as many as 90,000 people in the Late Classic period.42 Tik’al and other cities contained massive temple complexes and pyramids that are remarkably similar to those of the early civilizations in the Near East, although they undoubtedly reflect independent invention. By 600, civilization also had emerged in South America. The Andean states are distinguished from others by the absence of writing, although accounting and record keeping were performed with a system of knotted cords (quipu).43

All the complex societies that developed in the postglacial epoch redesigned their environmental settings in various ways. This began with the reorganization of plant and animal communities into gardens, crop fields, herds, and livestock pens. In many places, people created artificial waterways (canals), springs (wells), and ponds (reservoirs). But the most bizarre manifestations of this pattern were the created social environments of urban centers. Beginning with villages and towns, people built rectilinear houses with rectangular windows and doorways. The cities often contained orthogonal avenues and causeways, as well as large public buildings and plazas that were pure creations of the collective mind—geometric forms that bore little resemblance to features in a natural landscape. In some places, their immense size and the time and labor invested in their construction, reached the level of the absurd. They seem to have served no useful function from the perspective of human biology; the public ceremonies held at the temple complexes at Ur, Giza, or Tik’al could have been performed in an open field. Rather, they were symbols of the equally immense political structures that now dwelt on the Earth.

An Age of Stone

[A]ll knowledge of mind is historical.

R. G. Collingwood observed that the early civilizations had no concept of history. The “habit of thinking historically,” he argued, was a surprisingly recent phenomenon, dating no earlier than the eighteenth century.44The first nation-states instead saw themselves through the prism of myth, or what Collingwood labeled “theocratic history.” In both cases, past events were explained by the actions of supernatural beings.

The absence of a historical perspective in the early civilizations seems to reflect a cultural construction of time that was cyclical, rather than linear. It was a perspective both common and logical; time was perceived as a phenomenon that revolved continuously, as do the days, lunar months, and seasons. Such a perspective does not preclude history, but it does not demand or even imply it in the same way as does a linear concept of time. The modern linear construction of time, which has its own theological basis, developed in late antiquity.45 Unlike a historical narrative composed of an irreversible sequence of past events, a myth—as Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote—”explains the present and the past as well as the future”46 and is, as he famously suggested, an instrument “for the obliteration of time.”47

A preference for myth over history also reflects an aversion to change and would seem to be another manifestation of the reactionary and repressive character of the early civilizations—or, at least, their consistent failure to cultivate new ideas. By doing so, they slowed and, at times, almost stopped the process of history, especially if we define it in Collingwood’s words as “the history of thought.” The few available fragments of historical narrative provided by the early nation-states are largely confined to lists of kings and accounts of battles or natural catastrophes. There was no sense of progress toward a better world—a view that pervades modern life.48

Among the early civilizations, Egypt was the most successful in suppressing change and obliterating time. Despite major disruptions—which included the collapse of the Old Kingdom, foreign invasion and occupation, and a deeply disturbing challenge to religious doctrines (Akhenaten’s monotheistic “counter-religion” in 1352 B.C.E.)—the culture of ancient Egypt endured with minimal alteration for almost 3,000 years. The Egyptians steadfastly protected their traditional worldview—and the forms of language, art, and ritual through which it was expressed—from internal subversion and foreign contamination. As Jan Assmann observed, an educated Egyptian of the Roman period could have read and understood a Third Dynasty tomb inscription composed more than two and half millennia earlier. The longevity of Egyptian culture is without parallel and can be regarded not as a deficiency, but “rather as a special cultural achievement—indeed, one perhaps unique.”49

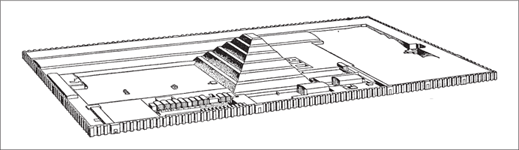

The familiar pattern of Egyptian ideology and art arose during the Early Dynastic Period and the Old Kingdom (3100–2150 B.C.E.). The construction in the early Third Dynasty of Djoser’s step pyramid (figure 5.5), which monumentalized the politically important sed festival, seems to have marked a critical turning point.50 But the earlier creation of hieroglyphic writing, which allowed the preservation of sacred texts, also was significant. The Egyptians insisted on repetition of the precise wording of these texts in ritual settings. This reflected a belief that the proper functioning of the universe could be ensured only by careful adherence to the form of the sacred.51

Ancient Egypt was a paradox. It became the most extreme example of conservatism among nation-states, but only after having become one of most revolutionary societies in history. More than any other early civilization, post-unification Egypt seems to have attempted a rapid replacement of the traditional organization of clans and villages with the idea of the nation. The government of the Old Kingdom implemented a social revolution from above that suggests parallels with the Soviet Union of the 1930s or other modern states that have forced radical social changes on the population. Egypt was divided into provinces (nomes) controlled by administrators that bore no relation to the earlier pattern of competing chiefdoms.52 Perhaps this is why the ideology and public symbolism of the Old Kingdom seems excessive.

Figure 5.5 The construction of Djoser’s step pyramid within an enclosure during the Third Dynasty in Egypt linked the sed festival, which celebrated the continued rule of a pharaoh, to monumental architecture and seems to have played a role in the emergence of a nation-state ideology. (From I. E. S. Edwards, The Pyramids of Egypt [Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961], 54, fig. 5. Reprinted with the permission of Penguin Books)

The revolution faltered at the end of the Sixth Dynasty (2150 B.C.E.), when the Old Kingdom collapsed and Egypt reverted to a group of regional political centers. Centralized government was restored in 2040 B.C.E., but unrest and civil war erupted within a few decades and lasting stability was not achieved until 1991 B.C.E. under the Twelfth Dynasty. The Middle Kingdom resuscitated the religio-political doctrines of the Old Kingdom and publicized them in new ways that paralleled the governmental propaganda of modern nation-states. The preceding period was officially recalled as a nightmare of chaos. A “police state” atmosphere prevailed.53 The pattern again is reminiscent of the Stalin era: the reactionary conservatism of a successful revolutionary movement.

By contrast, Sumer had developed in a very different way from Egypt, with the emergence of autonomous city-states. The social and economic hierarchy that represented early Sumerian civilization had arisen largely, it seems, through the “labor revolution” described earlier, including the managerial demands that accompanied it, and was not imposed from above.54 Perhaps the autonomous urban centers would have maintained the steady pace of innovation that preceded and accompanied their formation, but within a few centuries they were forcibly incorporated into a larger nation-state—first by one of the south Mesopotamian kings (2375 B.C.E.) and several decades later by Sargon, who united northern and southern Mesopotamia under the Akkadian state. The region was subsequently controlled by others, including the Babylonian and Persian empires. Although there were some advances in knowledge, especially in astronomy and mathematics, the rate of progress seems slow in comparison with that in the earlier period.55

The early civilizations of Eurasia were disrupted in various ways by the development and spread of iron technology after 1200 B.C.E. The critical innovations emerged beyond their borders and control. Once the technical challenges of iron smelting were overcome, the widespread distribution and accessibility of iron-ore deposits ensured the mass-production of cheap and effective weapons and farming tools. Another innovation from the uncivilized fringe that had both military and economic consequences was the domestication of the horse. Mounted cavalrymen with iron weapons toppled pharaohs and administrators, as states and empires rose and fell during the many centuries of conflict that followed. Iron technology also transformed Africa. Bantu-speaking peoples with iron implements had occupied most of the lands south of the Sahara by 1000 C.E.56

The later civilizations of Eurasia were less effective at suppressing change and innovation—especially in comparison with ancient Egypt. Among them, Greece made the most impressive contribution to the growth of the mind, and it may be significant that it began as a collection of autonomous city-states around 600 B.C.E. Inevitably, perhaps, they were incorporated into a larger political entity, initially as a result of the Peloponnesian War, which ended in 404 B.C.E., and subsequently by Philip of Macedon and his son Alexander, whose death in 323 B.C.E. is equated with the beginning of the Hellenistic period. And although the principal contributions to knowledge are usually attributed to the city-state phase, the most significant technical achievements date to the Hellenistic period.

During the earlier phase, there were some advances in architecture, which included the application of knowledge about optics and acoustics, and innovations in mechanical military equipment such as catapults. But the Hellenistic period (323–146 B.C.E.) produced a series of major breakthroughs in mechanical engineering that laid the foundations of industrial technology.57 Among them were levers, screws, gears, springs, valves, hydraulic pumps, and compressed-air devices. These technics were accompanied by brilliant mathematical work, which—anticipating Galileo—included the application of numbers to mechanics by Archimedes (287– 212 B.C.E.).58

Extenuating circumstances may have created a favorable environment for novelty and innovation in Greece, even after the autonomous city-states were subsumed under a central government. Much of the creative thinking of the Hellenistic period took place in Alexandria, a large and ethnically diverse city ruled for eighty years by the first three kings of the Ptolemaic dynasty, who actively promoted the growth of knowledge. The massive library at Alexandria represented another major contribution to the latter. It was an accessible storehouse of external memory on an unprecedented scale. Innovations also came from other cities that, like Alexandria, were outliers or colonies.59

But the application and dissemination of the engineering innovations of Archimedes and others were limited, and they did not have a major impact on Hellenistic society and economy. The primary applications seem to have been confined to ship design and military machinery. One constraint may have been a commonly expressed preference for abstract theory over practical use. Ultimately, these discoveries had little effect on how the ancient Greeks interpreted the world; they never developed the mechanistic outlook of the European clock makers.60

The history of Chinese civilization probably yields the most insight into the relationship between the organization of the nation-state and the growth of knowledge. This is because both the pace of innovation and the degree of political centralization varied significantly during the course of Chinese history, which followed a different path from that of western Eurasia. There were few or no major inventions in the millennia leading up to the formation of a nation-state around 2000 B.C.E.,61 and Chinese civilization began with something of a technological deficit relative to Sumer. But in the centuries that followed, key innovations were broadly applied, with profound effects on society and economy. The most significant were the development and spread of iron agricultural implements, including the plow, and irrigation systems, which took place during the Eastern Zhou period (770–221 B.C.E.) with substantial impact on agricultural productivity.62

The national political structure underwent dramatic changes before and during the Eastern Zhou period. The first two dynasties, Xia and Shang, had consolidated many but not all of the numerous towns scattered across northern China. The social hierarchy of these towns was based primarily on family relationships. The Eastern Zhou state disintegrated into smaller competing entities during the Warring States period (450–221 B.C.E.), recalling the collapse of the Old Kingdom in Egypt or the city-states period in ancient Greece. Like the latter, it is associated with a burst of creativity in philosophy and literature, as well as with technological advances.

China was reunified in 221 B.C.E. under the Qin dynasty, which embarked on a major expansion of central government power—crushing local landlords, establishing a national system of weights and measures, and even inaugurating monumental construction projects, including the Great Wall. The emperor promulgated an explicit ideology, Legalism, and burned books and executed scholars who expressed alternative ideas. But the Qin dynasty was short-lived, and China resumed its accumulation and expansion of knowledge under a succession of dynasties that exerted varying degrees of central control over the population.63

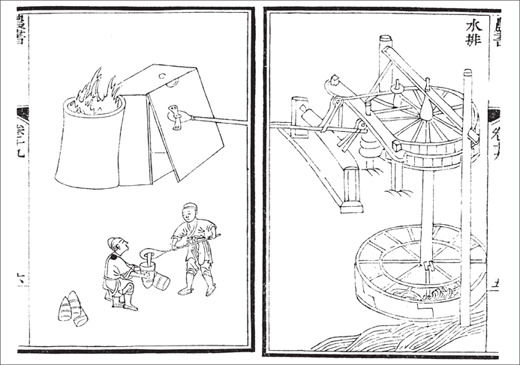

After 700, the rate of growth accelerated in many spheres of technology and China began to move toward an industrial economy far in advance of any other civilization in the world. Earlier developments in iron production led to coal-fired blast furnaces in northeastern China. In 1078, tax officials recorded a total production figure of 125,000 tons of smelted iron (figure 5.6).64 The earlier irrigation systems had led to advances in hydraulic engineering and water-powered machinery, such as trip hammers and bellows for the smelting furnaces. Moving water also was used to power Su Sung’s famous mechanical clock of 1092. There were innovations in textile manufacturing, including the mechanical cotton gin and water-powered spinning frame. All these developments were accompanied by a dynamic commercial economy and an expanding overseas trade, which was facilitated by the most advanced ships in the world, constructed with watertight bulkheads and navigated with the aid of a magnetic compass.65

The incipient industrial era came to end about 1400. The innovations largely ceased, and the activities of the merchant fleet were curtailed. China fell behind other civilizations technologically and eventually became vulnerable to smaller nation-states like Britain and Japan.66 The suppression of cultural change at this time is widely attributed to the policies of the Ming dynasty, which took over in 1368, used central government bureaucracy to discourage the growing power of industrialists and merchants. Foreign trade was prohibited in 1371 by imperial decree, and the construction of large ships was banned in 1436. Similar policies were continued by the succeeding (and final) Qing, or Manchu, dynasty.67

Figure 5.6 China appeared to be in the early stages of an industrial age roughly 1,000 years ago—and far in advance of Europe—with accelerating iron production, intensifying use of water-power technologies, and international overseas trade. This depiction of a smelting furnace with water-powered bellows dates to about 1300. (From Joseph Need-ham, Science and Civilization in China, vol. 4, part 2, Mechanical Engineering [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965], 371, fig. 602. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press)

The timing of the government crackdown may have been critical. Despite the widespread effects of the accelerating innovations in technology and their applications, the emerging pattern of industrial production and expanding commerce did not have a lasting impact on Chinese society and thought. Had continued growth been permitted, or even encouraged, by the central government, perhaps the modern world would have been largely a creation of the Chinese mind.

The Modern World as a Change of Mind

[T]here is an immediate and close connection between Christian ideas of creation and of the Kingdom of God and the development of modern technology. There is also a connection between Christian hope and the technological utopia of the future.

The central problem in the history of the modern world is why and how western Europe broke out of the creative stasis into which all civilizations fall sooner or later. The explanation lies in understanding how the creative powers of the mind, specifically of individual brains, can operate freely within the hierarchical structure of a nation-state. There is no obvious or simple answer to the problem, but—like the earlier emergence of farming settlements and civilizations—both environmental variables and specific historical factors seem to have played a role in what happened in Europe after 1200.

Western Europe occupies a unique position in the Northern Hemisphere with respect to temperature and precipitation. Clockwise currents in the North Atlantic Ocean ensure mild and moist climates despite comparatively high latitude. As a result, biotic productivity is higher in this region than anywhere else in northern Eurasia. In 1200, agricultural productivity and population density were rising due to the effects of a warmclimate oscillation (Medieval Warm Period). The available food surplus also seems to have increased, and a higher proportion of the population could pursue activities other than farming.68

In addition, the political and cultural landscape was unusual and possibly unique. Western Europe was divided into a chaotic tapestry of kingdoms and smaller political entities that had once been incorporated into the mighty Roman Empire. No central authority existed, and—as some historians have observed—no individual ruler or government had the power to suppress threatening novelties throughout the region, as did the Ming dynasty.69 At the same time, shared affiliation with the former Roman Empire provided a common language (at least for the literate) and church organization. The components of a large and diverse super-brain were integrated.

Several historians, most notably Ernst Benz and Lynn White, argued that the origins of the industrial civilization of Europe lay in the theology of Western Christendom. They emphasized the peculiar attitude toward the natural world articulated by many in the Western church, who, rather than seeking to live in harmony with it, viewed nature as a potential domesticate to be exploited, controlled, and, if possible, redesigned for human benefit.70 And far from being disdained, manual labor and practical achievements were regarded as virtuous. A deeply rooted Judeo-Christian construction of time as linear and progressive, rather than cyclical, may have created a more favorable climate for novelty.71

In any case, after centuries of stasis in farming techniques and technology under the Roman Empire, a succession of innovations after 700 laid the foundation for an “agricultural revolution” in Europe. They included improvements in the plow, toward a heavy wheeled design with a moldboard for slicing through turf, and the shift from oxen to more efficient horses for drawing it. And the use of horses required the development of a new type of collar and iron shoes to protect their hoofs from damage, especially in moist climates. Another critical innovation was move from Roman two-field crop rotation to a three-field system, which reduced fallow land from 50 to 33 percent each year.72 The combined effect of these changes seems to have been substantial increases in crop yields during the centuries leading up to and after the beginning of the Medieval Warm Period, which saw further increases as climates improved after 1000.

Historians have long debated the role of slavery in inhibiting technological innovation and, more broadly, social and cultural change among the early civilizations down through late antiquity in western Eurasia (that is, the Roman Empire). As slavery declined, the argument goes, incentives for new labor-saving technologies and general improvements in economic efficiency would have risen. Lewis Mumford thought that the critical issue was replacing human muscle with alternative sources of energy.73 In western Europe, such a trend became apparent by 800, with the growing application of water and wind power.

The technology for hydropower had been developed much earlier than the eighth century. There is evidence of water wheels in ancient Greece as well as in the Roman Empire. Indeed, the Romans made some improvements in their design.74 The difference lies in the widespread use of water power during the later Middle Ages. By 1086, tax records indicate no fewer than 5,624 water wheels spinning in southern England alone. The generated mechanical energy was employed primarily to grind grain, but also saw other applications, including to power trip-hammers. In some coastal areas, where stream gradients were low, tidal mills were constructed.75

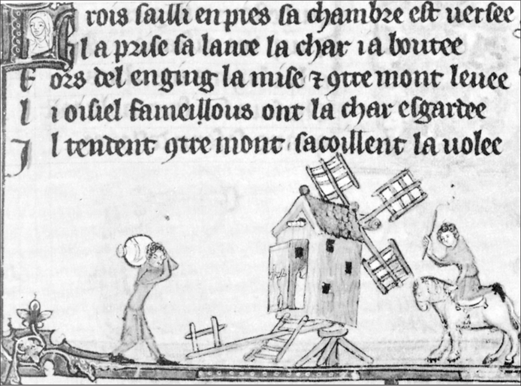

The windmill, though—first reported in Iran by 700—was a post-Roman invention.76 Although wind power had been used to propel boats and ships for several thousand years, the idea of applying it to the generation of mechanical energy was apparently derived from knowledge of water wheels. The effective adaptation of the technology to moving air required the development of a revolving pedestal in order to adjust the position of the wheel to shifting wind directions. In western Europe, windmills were widespread before 1200 (figure 5.7). No fewer than 120 of them were operating near the Flemish town of Ypres by the end of the thirteenth century.77

The mechanical technology that Mumford termed the “key machine” of the industrial age—the weight-driven clock—was engineered somewhere in western Europe around 1250.78 Its advent and far-reaching consequences for technological development and worldview were mentioned in chapter 1. In one respect, the weight-driven clock was regressive because it ultimately relied on human muscle power to provide the energy. The escapement mechanism, designed to release the stored energy, was a major technical achievement, however. And it was the first machine built entirely of metal. The chief incentive apparently was to create a device for the timing of prayers in monastic orders that was more accurate and reliable than the water clock.79

The impact of the mechanical clock on the human imagination was considerable. Clocks were, as David Landes remarked, “like computers today, the technological sensation of their time.”80 The clock makers became a new category of technical specialist, and their knowledge and skills found applications to other technologies, such as water wheels. Clocks eventu ally spread to every community and created an arbitrary temporal matrix within which virtually everyone functioned. They generated the temporal component of the daily landscape of the mind. They became a model and metaphor for the entire universe.

Figure 5.7 Both water- and wind-powered technology became increasingly widespread in western Europe during the late Middle Ages. (From Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress [New York: Oxford University Press, 1990], 45, fig. 10. Reprinted with the permission of Oxford University Press)

The work of the clock makers was enhanced by another important innovation before 1300: eyeglasses.81 The invention of spectacles reflected expanding knowledge of the properties of glass and how to manipulate them to achieve yet another step toward remaking the human organism. Yet despite the discernible momentum in harnessing new sources of energy and inventing new technologies, western Europe experienced a slowdown and something of a backlash during the fourteenth century. Catastrophic death and population decline were caused by severe famine in the second decade of the century, followed by outbreaks of plague, especially the so-called Black Death (1348–1350), which wiped out at least one-third of the population of Europe. Wars and violent uprisings erupted. There was a surge of interest in religious mysticism and a corresponding obsession with witchcraft.82

The pace of innovation resumed during the fifteenth century, which became the critical turning point for the emerging construction of reality that became the modern world. The invention of movable type and the printing press in 1455 had consequences on the same scale as those of the mechanical clock. Within fifty years, more books were produced than had been in the preceding thousand years.83 Information was communicated among the disparate elements of the collective mind, stimulating new thought, and stored in readily accessible form for future generations. It was the most significant development in information technology or neurotechnology since the creation of writing.

Another innovation with fateful consequences was the adoption of gunpowder, probably from China, and its application to the propulsion of projectiles. Despite many advances in the catapult by the ancient Greeks and later improvements in the crossbow, the fundamental design of projectile weaponry in 1200 had not changed since the late Upper Paleolithic. A heavy projectile propelled by an explosive force in a metal tube represented a potentially major increase in power and range. The earliest cannons are reported from the early fourteenth century; during the fifteenth, they became larger, more mobile, and more common. Competition and conflict among the fragmented political entities of western Europe ensured a perpetual arms race that yielded regular improvements in military technology.84 And armies in western Europe were deployed in marching formations with increasing precision, reproducing the hierarchical organization of the military in simple geometric shapes on the landscape.

European artillery and small arms also ensured an overwhelming military advantage over other peoples. Firearms played a role in the exploration of the world (in conjunction with diseases), which was initiated in the fifteenth century. Although the impact on non-European local populations and cultures was catastrophic, and the economic benefits were problematic, the people of western Europe became the first to acquire a knowledge of the planet as a whole. Like the mechanical clock, the expanded concept of the world had a powerful effect on their imagination. Some improvements in ship design and navigation were essential, such as the axial rudder and compass (also from China), but Fernand Braudel argued that the most important factor was psychological: overcoming the fear of sailing across vast expanses of ocean like the Atlantic.85 This reflected perhaps a wider change in attitude toward the natural world.

The relationship between the acquisition of knowledge through both technological innovation and contact with other peoples and the construction of reality is illustrated on a grand scale in Europe between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. The accelerating pace of innovation after 1200 not only yielded a new body of knowledge about materials and processes of the surrounding world, but tipped the balance toward a novel construction of reality based on the model of the machine. By the end of the seventeenth century, Lewis Mumford wrote, “there existed a fully articulated philosophy of the universe, on purely mechanical lines, which served as a starting point for all the physical sciences and for further technical improvements.”86 The “scientific revolution” was led by a small group of people scattered across western Europe, including Georg Bauer (Agricola, 1494–1555) in Germany, Galileo (1564–1642) in Italy, Descartes (1596–1650) in France, and Francis Bacon (1561–1626) in England. For the first time since the Lower Paleolithic, the function of the sensory hand was understood and the acquisition of knowledge was tied explicitly to physical experimentation: technology applied to science. Whenever possible, processes were described mathematically; when necessary, mathematical knowledge was expanded for this purpose, such as the invention of calculus.87

To some extent, the Europeans redesigned the mind itself. Although brain function had been altered technologically since the creation of mnemonic devices in the early Upper Paleolithic, the creative powers of the mind either had been left free to roam, although always constrained by social setting, or had been suppressed by priests and police. The revolutionary scientists recognized the need to manipulate creativity by testing alternative realities under controlled conditions and by minimizing the subjectivity of the brain. The early civilizations had applied mathematics to technology—now it was applied to thought.

The rewards of creativity finally were recognized, even by kings, and a previously unknown sense of forward momentum was emerging. In 1306, Dominican Fra Giordano of Pisa noted both the benefits and the novelty of spectacles, invented within his lifetime, and remarked that “not all the arts have been found…. Every day one could discover a new art.”88 The sense of progress was a new form of super-brain consciousness that reflected an awareness of historical or cultural rather than biological linear time. Not only could the enlightened and innovative present be distinguished from the ignorant and backward past, but an alternative future reality—a paradise of knowledge—could be imagined with confidence. Francis Bacon was particularly outspoken in his vision of technological progress. He saw not only the limitations of the past, but also the potential of the future, describing a world with submarines, aircraft, research labs, telephones, and even air-conditioners.89

People Without History?

[S]ome savages have recently improved a little in some of their simpler arts.

As European explorers spread across the oceans and disembarked on strange shores, they encountered a wide range of people previously unknown to them. In Mexico, they confronted a technologically primitive civilization with a major urban center. In the central Pacific, they saw chiefdoms composed of thousands of individuals. In the Arctic, they were impressed with people who inhabited large villages without benefit of agriculture. In some places, they discovered nomadic foraging societies equipped with very simple technology.90

Europeans of the eighteenth century were especially struck by the native people of Australia, who had little in the way of clothing or equipment. They came to be viewed as the most primitive of all peoples. When William J. Sollas published Ancient Hunters and Their Modern Representatives in 1911, he presented them as typical of Middle Paleolithic (and non-modern human) foragers. Even more primitive, Sollas asserted—and evocative of the Lower Paleolithic—were the already extinct natives of Tasmania (a large island off the southeastern coast of Australia).91

The discovery of a wide range of societies and cultures—from the very small and simple to the large and complex—had a powerful effect on the European imagination. Simple foraging societies like the native Australians aroused special fascination; they seemed to be “living fossils,” offering a glimpse of earliest humanity. They provided further support to the view of history as progress. Indeed, it would appear that encounters with “primitive societies” had as much, if not more, impact on thinking about social and cultural evolution as did the discovery of ancient artifacts and the recognition by the early nineteenth century that they, too, could be organized into a sequence of evolutionary progress.92

The existence of such societies posed a question in this context: Why had some cultures failed to develop agriculture, power technology, and large settlements? Why had some people remained at what seemed to be a Middle or even a Lower Paleolithic level of society and culture? A widely accepted answer to this question in the nineteenth century was that the contrasts in technology and organization between modern and premodern societies reflected biological differences: primitive societies were the product of inferior races.93 Such a view not only was morally objectionable, but was then and remains without any credible supporting evidence. In the years since their initial encounters with European explorers, most of these populations have adopted contemporary technologies and become part of complex societies. The global differentiation that began with the movement of modern humans out of Africa 50,000 years ago and their dispersal throughout the world has been in reverse for several centuries. As this trend continues, the differences among various peoples that seemed so fundamental to the Europeans will be understood as the consequence of historical factors.

An alternative explanation was environment: foraging peoples and other simpler societies encountered by European explorers inhabited places with severe limitations on growth and development. In many cases, this seems to be a valid explanation. Recent hunter-gatherers often have been found in desert margins, arctic tundra, or other environments where the potential for agriculture and population growth is constrained by aridity or cold. There are exceptions to the pattern, however. Some foraging societies of the recent past have occupied habitats with clear potential for domestication and sedentary settlement. And anecdotal evidence suggests that some of these foragers were well aware of the possibilities and requisite techniques for the cultivation of plants. They simply preferred their traditional way of life.94

One reason why Europeans misjudged foraging societies during the seventeenth and later centuries is that they lacked a historical perspective on them. With a better knowledge of the archaeological record of modern humans in Australia, southern Africa, northeastern Asia, and other regions, it becomes apparent that all of them have changed over time. With the advent of the mind and the spread of modern human groups, truly static cultures like those of the Lower and Middle Paleolithic vanished. The native Australians, for example, who comprise a diverse array of people living in a variety of habitats, have experienced nearly continual change since their arrival more than 40,000 years ago.95 Even groups equipped with the simplest technology have created novel implements that probably were unknown in the early or middle Upper Paleolithic.96

At the same time, rates of change clearly have varied considerably. A slow pace of innovation and change may indeed reflect local environmental variables. But historical factors also seem to be at work. Roughly 2,000 years ago, for example, people in the Bering Strait region engineered some complex technology related to whale hunting that had significant social and demographic consequences. Their neighbors farther east—known to archaeologists as Late Dorset—did not, and there is evidence that they had actually discarded some of their earlier innovations, such as the bow and arrow.97 Like nineteenth-century China, the Late Dorset people fell prey to more technologically advanced foreigners, at least partly as a result of their own historical trajectory. Even without a rigid hierarchy and centralized government to suppress innovation, the Late Dorset seem to have been particularly resistant to change; perhaps this also was a significant factor among other foraging societies.