5

London in Wartime (1913–19)

“I’m hanged if I didn’t fall in love with her.”

—Adrian Allinson, “A Painter’s Pilgrimage’1

“I pulled a chair up to the table, opened an exercise book, and wrote: This is my Diary. But it wasn’t a diary . . .”

—Jean Rhys, “World’s End and a Beginning,” Smile Please

NO EARLIER DRAFTS or manuscripts survive to contradict Jean Rhys’s assertion in Smile Please that she first began writing seriously during her prewar life in Chelsea. Although she doesn’t say what happened next, it is clear that these early writings continued through the war and that they were later cobbled together as the episodic, unpublished work named “Triple Sec” by Rhys’s first literary patron after the dry, crystal-clear and unexpectedly potent French liqueur.

“Triple Sec,” previously dubbed “Suzy Tells” by another of Rhys’s literary mentors, is narrated by a young woman. While the tough but vulnerable Suzy speaks for her creator, certain true-life experiences that she undergoes have been embellished and rearranged to produce a fictitious outcome. “Triple Sec” cannot be treated as pure autobiography, but it does offer some helpful clues about Rhys’s personal life before and during the war.

THE YEAR 1913 had been a testing time for Rhys, crushed by the sense, aged twenty-three, that she had failed in both her stage career, and in love. In April 1914, however, her life grew brighter after a clever and party-loving political journalist called Alan Bott (he later helped to create the Folio Society and Pan Books) enrolled his new friend as member of a private nightclub that had recently opened in Soho.

The Crabtree was founded as a congenial meeting place for his friends by the Welsh painter and draughtsman Augustus John, then at the height of his fame, and financed by John’s affable and literary-minded patron, Lord Howard de Walden. Three rickety flights of stairs up from a narrow doorway on Greek Street, the little club was cheerily shabby. Stella Bowen, disapproving of the Crabtree’s lack of formality (women wearing trousers, worryingly unmanly men and “nobody in evening dress!”), was equally unimpressed by its decor: “Beer marks on plain deal tables, wooden benches, and a small platform on which a moonfaced youth made music for a bevy of gyratory couples.”2 Informal boxing matches were sometimes held here; two good-looking singers of the time, Betty May and Lilliane Shelley, offered impromptu cabaret turns. On one occasion, a baffled Stella Bowen heard the futurist poet Marinetti orating one of his “zoom-bang” songs in Italian at the Crabtree; on another, one of the club’s two rival crooners performed an early form of pole-dance by shinning up the wobbly fruit-topped post from which the club derived its name.

The Crabtree’s scruffy furnishings were unimportant. Paul Nash, Henri Gaudier Brzeska, Wyndham Lewis, Nina Hamnett, Mark Gertler, Jacob Epstein, Marie Beerbohm, Henry Lamb, Compton Mackenzie: the list of its members reads like a guide to prewar bohemia. A crucial reason for the club’s appeal to this youthful group was that basic food and hard liquor were cheap (an honesty box was provided by the door) and members could loiter until dawn—the Crabtree didn’t even open its doors until midnight—to dance or to lounge and chat. In After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, Julia Martin and George Horsfield visit a club clearly based on the Crabtree. Julia settles in straight away and starts dancing with a stranger; sober George looks on, feeling awkwardly out of place.

Clubs were starting up all over London in an era when writers regularly lunched at Soho’s accommodating Eiffel Tower (its sparsely furnished bedrooms were in great demand), while a skittish young Nina Hamnett swigged iced crème de menthe beneath the blind stare of the Café Royal’s gilded caryatids. August Strindberg’s widow presided over “The Cave of the Golden Calf” in a lavishly decorated basement near Piccadilly Circus, until it went bankrupt in 1914; Jean Rhys preferred the noisy little rooms high above Greek Street. I like to imagine seductive Ella whirling around the floor with my grandfather, the generous, art-loving peer whose deep pockets helped to keep that jolly little club afloat. More certainly, it was during an early visit to the Crabtree that the “tender loveliness” (Adrian Allinson’s striking words) of Jean Rhys’s appearance caught the eye of one of Alan Bott’s fellow journalists.

Maxwell Hayes Macartney, an artist’s son and the brother of a political historian, had trained as a lawyer, before switching professions to become a specialist on European affairs at The Times, where he worked alongside Bott. Ten years older than Rhys, Macartney was instantly smitten by the delicate features and wistful expression of a young woman who could imaginably have been painted by Botticelli. It was during a teatime feast in Macartney’s rooms, where hot buttered toast and sponge cake were appreciatively consumed by a hungry visitor, that Rhys received an impulsive proposal of marriage. Acting from honour or reluctance, she discouraged her host with lurid tales of her life on stage and in Chelsea.* Despite his subsequent hesitation about setting a precise wedding date, Macartney persisted. An agreement to marry was reached, but theirs—so Rhys would nonchalantly comment in Smile Please (she never identified either Macartney or Hugh Smith by name)—would remain an “on-and-off” engagement.

Rhys was a little more forthcoming about Macartney (lightly disguised as “Ronald”) in “Triple Sec.” There, while describing the flat where she visits “Ronald” in the Temple, Rhys fused it with the nearby home of Arthur “Foxie” Strangways. Located in an area popular with lawyers and conveniently close to Fleet Street for journalists, Macartney’s Temple rooms were crammed with books, while signed photographs and informal sketches of Chesterton and Shaw hinted at illustrious friendships. Like the old-fashioned “Foxie,” Macartney dressed in tweeds and washed his lean limbs in a tin hip-bath. Unlike Fox Strangways, he also played golf and expected to be cheered on by his sports-averse fiancée.

In July 1914, shortly after meeting her new beau, Miss Ella Gray returned to the stage, playing one of the besieged inhabitants of Renaissance Pisa in Maurice Maeterlinck’s scandalous Monna Vanna (first performed in 1902). The source of outrage—and full houses—was a scene in which the playwright required Monna Vanna (played by a voluptuous Constance Collier in an all-concealing cloak) to appear naked onstage. A ban on evening performances—in case the mere thought of Collier’s body beneath her strategic mantle might incite turmoil in the stalls of the Queen’s Theatre—enabled Rhys to continue dancing and drinking long after midnight at the Crabtree. She was heading for the club with her fiancé on the night when they spotted, in Leicester Square, a news-stand poster announcing the assassination of an Austrian archduke at Sarajevo. The consequences of that disastrous event would sink in gradually, less when Macartney went out to France in November as a war correspondent (“Suzy” remembered sadly packing her fiancé’s favourite tweed suit), than when Rhys’s beloved Crabtree closed its doors in December 1914, “for the duration.” We don’t know if the news reached her, or whether she cared, that Lancey’s adored young cousin Julian Martin Smith had been the first volunteer officer to die in action.

THE AGGRESSIVE LOYALTY to Britain and the Empire which Rhys displayed during the First World War suggests that she had always managed to maintain vestigial contact with her family in Dominica. Out in the Antilles, the belligerent jingoism of the white settlers was infectious. Only a few stalwarts of the all-white Dominica Club sailed home to enlist; it came as a shock to the patriotic village youths who signed up to fight for king and country when they found themselves assigned to an all-black West Indian regiment in an army that had promised equality to every creed and colour within its enlisted ranks.† In London, Rhys felt strongly enough about the war to declare that any man who failed to fight for England was a coward. Her views helped to influence Macartney’s courageous exchange of his role as one of the war’s most respected correspondents—like the fictitious “Suzy,” Rhys conscientiously followed her lover’s bulletins in The Times—for that of a middle-aged soldier at the front.

Macartney’s flat felt cosily safe from the German zeppelins which began to launch raids on London in 1915. (Nina Hamnett, who once narrowly escaped stepping aboard a bus that was promptly blown to bits by a zeppelin bomb, later recalled a night when she tiptoed ankle-deep through shattered glass along the Strand to keep a date at the Café Royal.3) Perhaps Jean grew guilty about lolling among her fiancé’s volumes of Chesterton and Wells while, outside the flat’s rattling Georgian windows, the city was besieged. Still aged only twenty-four, she volunteered to work long daily shifts at an army canteen that had been set up at Euston Station, where soldiers travelling down from Scotland and the north made their connection to Charing Cross for the last leg of their journey to the Channel ports.

Lightly though Rhys dismissed her war work in Smile Please, her self-imposed assignment was a tough one. Organised by a couple of formidable army wives, the Euston canteen’s soberly dressed female staff (gloves and neat black hats were mandatory) committed themselves to frying up plates of hearty food and offering encouragement to their soldier clients. By early 1915, at least 600 men were being shunted through the station every day; on Platform 12, eighteen camp beds were kept ready for injured and disabled soldiers returning home. Anybody working at the canteen as Rhys did, for nine hours a day, over a period of almost two years, became a witness to the horrors of war.

MACARTNEY’S LONG ABSENCES in France enabled Jean to take a relaxed view of what might be expected of herself as a deserted fiancée, living under his roof. In the summer of 1915, she gladly accepted an invitation from the lovesick Adrian Allinson to come and spend a few off-duty weeks at a cottage in the Vale of Evesham, deep in the bucolic Gloucestershire countryside and close to Crickley Hill. Sweet though Allinson’s personality was, and greatly though she admired the earnest young man’s uncompromisingly realistic paintings (he had helped to found the London Group, after studying at the Slade alongside Gertler and Stanley Spencer and spending two years on the Continent), Rhys felt no sexual spark. It was the prospect of free hospitality and fresh country air which made Allinson’s suggestion irresistible, together with the news that their companion at the cottage would be Philip Heseltine. She may not have expected a brilliant young man, better known for his poetry than his music at that stage of his life, to be accompanied by his beautiful girlfriend, an artist’s model called Minnie Channing.

Tall, fair and athletic, with exceptionally blue eyes and a disturbing reputation for physical violence, Philip Heseltine came from a privileged background of wealth, as did Allinson, with whom he had gone on several mountaineering expeditions during their prewar months on the Continent. Rhys was uncertain what to make of him, but the forcefulness of Heseltine’s personality made him impossible to ignore. On one well-attested occasion, after dinner, Heseltine suddenly stripped off his clothes, jumped onto his motorbike and roared off, stark naked, up a moonlit Crickley Hill. In the moments when he wasn’t squabbling with Minnie (known as “Puma” for her fierce temper), he might either whistle plaintively as a curlew, or serenade his housemates with some melody from Frederick Delius, a British-born composer with a German mother, whose reputation was unjustly clouded by the war. Heseltine worshipped Delius, whom he had first met personally during his schooldays at Eton, and who treated him as a pet protégé. While Allinson was earning a living in wartime by designing sets for Sir Thomas Beecham’s opera company and doing sketches for the Daily Express, Heseltine had taken a five-month job in 1915 as a music critic for the warmongering Daily Mail, largely in order to promote the temporarily banned compositions of his hero.

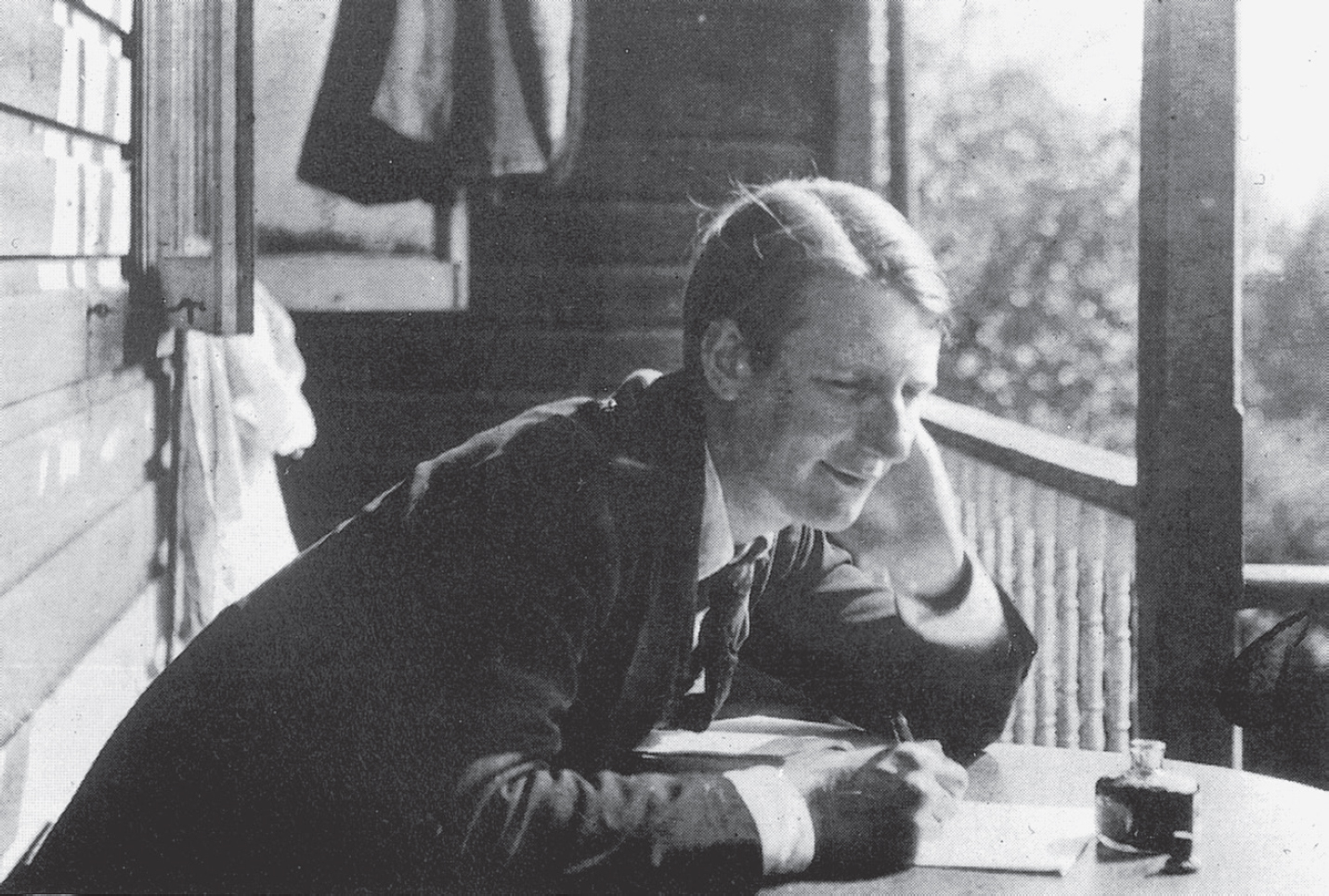

The charismatic young composer Philip Heseltine, who later took the name Peter Warlock, photographed at the country cottage which he shared with Rhys and two friends in the summer of 1915.

The best-known account of what happened during Rhys’s stay at the Gloucestershire cottage would eventually be published in 1960, in a story which had passed through many stages of careful revision. “Till September Petronella” mixes fact with fiction as bewilderingly as does the account of this same country holiday that Rhys had earlier described in the unpublished “Triple Sec.” Only by comparing both of these versions of events with a third—the more artless account offered in Adrian Allinson’s unpublished memoir, “A Painter’s Pilgrimage”—can we glimpse what actually took place at the crowded cottage.

“A Painter’s Pilgrimage” records a memorably unsatisfactory episode in Allinson’s life from the point of view of a half-German artist, a sensitive and rather brilliant young man who shared his friend Heseltine’s passionate hatred of war. Viewed with hindsight by Allinson, the holiday was doomed from the start. Heseltine and Minnie Channing formed an instant bond of dislike for Adrian’s vociferously bellicose girlfriend; urged to pack her bags and take her beastly opinions back to London, “Ella” displayed what Allinson would describe as “a streak of hard determination oddly at variance with her outer frailty.” When Philip and Minnie said they couldn’t even bear to eat in her presence, his guest calmly retreated to her bedroom, where she seemed content to spend hours rubbing creams into her face, languidly combing her hair and—as always when left on her own—reading. The more that the couple attacked her, the more firmly Ella withdrew. When Allinson, still a virgin at 24, sought sexual favours in return for his own resolute loyalty, Ella coolly announced that she was tired—and closed her door.

“Triple Sec” is less trustworthy than “A Painter’s Pilgrimage.” The relationship with Allinson is coyly presented here in the format of “a semi demi love affair”; unlike Allinson’s Ella, Rhys’s “Suzy” walks out on her squabbling housemates. On the contentious issue of war, however, “Triple Sec” proves enlightening. Confident of the rightness of her views, Suzy becomes forthright and even rude. “Why aren’t you at the war anyway?” she demands; a white-faced Forrester (unmistakably based upon Heseltine) leaves the room at once. Here, there is no doubt that Suzy’s own aggression was the cause for the “instantaneous and violent” hostility to which she (like Rhys) has been exposed.

“Triple Sec” provided the embryo for one of Rhys’s finest stories. Parts of “Till September Petronella” are fictitious. Allinson’s offended girlfriend did not flee the cottage with the help of a sympathetic “Marston” (the name Rhys eventually picked for the Allinson figure in her published story). Philip Heseltine (“Julian Oakes” in “Till September Petronella”) may not have mocked Rhys’s voice as “a female pipe,” but certain of Julian’s cruel remarks do sound authentic: the vicious-tongued Heseltine was entirely capable of having called Allinson’s jingoistic girlfriend “a female spider” and even “a ghastly cross between a barmaid and a chorus girl.” In Rhys’s version of the past, Julian Oakes’s hatred is fuelled by the suspicion that Petronella Gray is only interested in his pal (described here by Rhys as one of England’s finest young artists) because of Marston’s wealth. While it’s beyond proof that Heseltine expressed such a cynical view at the Crickley cottage, it’s certainly not beyond belief.

Rhys admired Heseltine’s musical gift and—perhaps—his devotion to Delius. “He is the great Julian,” she allows Marston to say in defence of his brilliant but volatile friend. “He’s going to be very important, so far as an English musician can be important.” But those words were written long after Heseltine, having renamed himself Peter Warlock in mocking acknowledgement of his interest in diabolism, had taken his life by gassing himself in 1930, aged only thirty-six. While Rhys’s story recognises Heseltine’s musical artistry, it also honourably records her absolute failure to please or impress him during the Crickley cottage holiday.

Returning to London from a disquieting month in the country, Rhys gladly resumed her perch in Macartney’s flat during his own continued absence at the front. A restful home richly supplied with books offered a welcome refuge after her long days at the Euston station canteen. Or perhaps not: Julia, in After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, alludes to “the mad things one did” during the war. If Rhys, too, did “mad things,” she kept them to herself.

ASSIGNING DATES TO Rhys’s wartime life is difficult. Circumstantial evidence suggests that it was after the closure of the canteen in 1917 that “Ella Gray” contacted Blackmore’s Agency once again, hoping for work in the surprisingly active world of wartime theatre. Soon after this, Rhys fell ill. Details are scant. “Triple Sec” refers only to “a slight operation,” but it was serious enough to require three weeks at a London nursing home (for which Lancey Hugh Smith, still paying Rhys a regular allowance, may have footed the bill), followed by a short recuperative holiday in the country.

Despite the fact that “Triple Sec” expressed gratitude to the sister of Maxwell Macartney for looking after her during this second, convalescent stage, it was at this vulnerable time that Rhys’s fiancé broke off their engagement. “Suzy” describes “Ronald’s” haggard appearance when he returned on leave. Macartney may have been shellshocked: the effect of exchanging work as a prominent war correspondent for life under fire must have been devastating to a man in his mid-thirties. Accused of bringing “numerous men friends” back to her fiancé’s flat, Suzy is brusquely ordered to get out. (So far as is known, Rhys herself never saw Macartney again.) In “Triple Sec,” a narcissistic Suzy describes the impact on her own fragile sensibility. “I’m one of the weak ones and I’ll always be hurt,” she states, and—a few lines later: “Lay thinking of nothing at all—just tired. Self confidence blown out like a candle.”

Rhys herself always responded well in a crisis. While still recovering from her “slight operation,” she moved into cheap lodgings in Bloomsbury before making a final attempt to relaunch her stalled stage career. Suzy’s dance teacher (Madame Zara) is sufficiently pleased by her pupil’s progress to predict a bright future in “acrobatic” ballet (a form of near-nude but tastefully static classical dancing not far removed from Emma Hamilton’s notorious “attitudes”). Rhys herself was still taking ballet lessons when she found more conventional work as a sifter of war-related correspondence at the newly founded Ministry of Pensions.

How did an untrained former chorus girl obtain such a job? The answer probably lies with the well-connected Lancey Hugh Smith. Operating out of the Royal Hospital in Chelsea, the government’s brand-new ministry had been put in charge of organising the payment of pensions to members of families affected by the war. More employees were urgently required; Rhys was a well-dressed and softly spoken young woman who may have arrived carrying a personal recommendation from the influential Mr. Hugh Smith. She made a welcome addition to the busy team of sixty women whose challenging daily task it was to read and assess the sackfuls of heartrending appeals submitted by maimed soldiers and destitute widows.

The work was both hard and bleak. Britain’s new coalition government favoured a more egalitarian approach, but the system of which Rhys now gained first-hand experience still consistently favoured the privileged above the deserving. The size of a widow’s pension was dictated by her husband’s rank, as were the education grants grudgingly doled out to his sons. In the navy, only the widow of an admiral was eligible for a government handout. In the army, a soldier’s death from disease was shockingly and regularly blamed on personal “negligence”: no question of a pension for his widow. The family of a soldier released because of a war injury qualified for a pension only after—and if—he died within seven years of his resignation.4

Such disillusioning daily employment, combined with the shabby way she felt she had been treated by Lancey and Macartney, ended Rhys’s colonial fantasy of an innocent England. She didn’t move to a cheap attic room in Torrington Square for safety—a zeppelin bomb destroyed lives in neighbouring Endell Street—but because the double-fronted Bloomsbury lodging house was packed with refugees from abroad; aliens, like herself. The landlady ran a tight ship; rebuked (once again) for an excessive use of the household’s hot water supply for her baths, a mortified Ella was defended by a friendly fellow lodger.

Rhys would write with unusual tenderness in the English section of Smile Please about her chivalrous supporter. Camille (the only name by which we know him) was a university-educated émigré from Bruges. Little jokes about robbing the bank for which he worked as a cashier in order to fund their elopement were light-hearted banter between friends; Rhys knew how devoted the calm, bespectacled Belgian was to the elderly wife who co-hosted their weekly “nursery teas,” held in a welcoming room filled with interesting people. Camille, in his spare time, was writing a book about the Noh theatre of Japan. One guest was an Icelandic poet; another was a dark, tousle-haired and fine-featured young man whom Camille introduced as Jean Lenglet (pronounced “Leng-lett”).

Camille identified his twenty-eight-year-old friend as Belgian; Lenglet, a man of mystery from the very start, described himself as Franco-Dutch. Asked out to lunch, Ella decided that this intriguingly reticent man with sensitive hands was both kind—he rebuked her for using the chorus girl’s cheap trick of drawing attention to a plainer woman in order to highlight her own attractiveness—and generous: years later, Rhys would fondly recall Lenglet’s purchase of an expensive box of her favourite Egyptian cigarettes, a large bottle of exotic scent and—at her own special request—a glass pot of kohl with which to outline her immense blue eyes. Escorted back to Torrington Square, or possibly to a dance lesson with Madame Zara (he was sceptical about Ella’s stage future), she was baffled when Lenglet simply shook her hand and left. Such sedate behaviour was unusual in wartime London. Lenglet’s reticence greatly increased his allure.

Smile Please jumps straight from that memorable first date to Lenglet’s proposal of marriage. Between times, Camille, Lenglet and Rhys often spent their evenings drinking at the Café Royal. Here, the seemingly wealthy Lenglet talked about himself, but only on prescribed topics. He captivated francophile Ella with stories of running away from his strict Jesuit school to become a teenage chansonnier in Montmartre; he may have mentioned penning the occasional article about Montmartre for the Paris-based New York Herald Tribune. But his story of leaving a family home in the Netherlands in order to join the French Foreign Legion failed to disclose that he had served for just one month. No explanation was offered for his presence in England; no mention was made of the second wife, Marie Pollart—he had married her predecessor in Antwerp in order to legitimise a baby son—with whom Lenglet lived in Paris until 1913, while sharing rooms with her widowed mother.

At the end of 1917, the landlady of Torrington Square invited her lodgers to a fancy-dress party. A scraggy roasted fowl was served as a suppertime treat. (“Don’t laugh,” kind Camille whispered to Ella as she began to giggle: “she’s awfully proud of having got that chicken.”5) The star of the party was one Simone David, a young Frenchwoman whose large bedroom on the first floor was filled with pretty clothes and dashing hats.‡ Perhaps it was Simone who loaned her admiring friend the black-and-white Pierrette costume that Rhys remembered having worn that momentous night.

In her memoir, Rhys would relate the evening’s events in fairy-tale style. Leading her outside—where, naturally, a huge full moon waited to beam approval—Lenglet took Ella by the hand and asked her to marry him. Only because of her—he now explained—had he courted danger by remaining in London. He didn’t say why he was in peril, only that he must leave the country the following morning. Later, when the war was over, he would send word for Ella to join him in his beloved Paris. Could she wait? “It came to me in a flash that here it was, what I had been waiting for, for so long. Now I could see escape.” His gentle kiss seemed to promise an enchanted Rhys that she would be forever cherished by this romantic man. Her acceptance was unhesitating.6 Fuelled by fantasies of adventure and escape, she was impatient for her summons to come.

Not everybody shared the newly abandoned Ella’s sense of excitement. At the boarding house, only Camille was encouraging. A three-page letter arrived from Rhys’s younger sister, Brenda, out in Dominica, warning her against such folly.§ It is unclear which members of the family actually succeeded in visiting her in London in 1918, or what was said, but it’s evident that a mysterious stranger from the Continent was not regarded as a marvellous catch.

The end of the war ushers in a curious silence in Rhys’s life. If a young woman disillusioned by her own work at the Ministry of Pensions chose to join the three days of celebrations when the Armistice was announced in November 1918, she kept that fact to herself. Early in 1919, however, as steamers began to resume their normal cross-Channel traffic, Rhys agreed to join Lenglet at The Hague. Joyfully, she wrote to tell Lancey to stop paying the solicitor’s cheques.

Previously thought to be of Brenda Rees Williams as a young woman at school in London. Brenda’s schooling was cut short by the war. More likely, this dates from the year when Brenda wrote from Dominica to censure her older sister’s choice of fiancé. (McFarlin)

The news that Lancey wanted an urgent meeting caused a flicker of apprehension. Aged twenty-nine, Rhys remained in awe of her first lover; reluctantly, she agreed to meet him for lunch at the smartly conventional Piccadilly Grill.

The cruelly premature death, back in 1914, of Julian Martin Smith had devastated Lancelot Hugh Smith. He himself had gone on to enjoy what is known as a “good” war. His negotiating skills had helped to keep Norway and Sweden free from the grasp of the Central Powers and in 1917, he became one of the very first recipients of a CBE. Politically, as in the world of finance, he was uncommonly well connected. Seen from the perspective of a nervous lunch guest—as Lancey steered a carefully neutral conversation towards her plans—Mr. Hugh Smith appeared to know everybody, and everything.

What emerges from this encounter—and from Lancey’s urgent entreaties that “Ella” should break off her relationship with Jean Lenglet—is that this shrewd, conventional and quietly unhappy man remained on some deep level in love with his “kitten,” the enchanting young woman he himself had refused to marry, and that Rhys herself had lost none of her reverence for him. Quietly, she listened as Lancelot revealed all that he had ascertained. None of his news was good. Lenglet’s passport was invalid (due to the critical loss of his Dutch citizenship when he had impetuously joined the French Foreign Legion). In England, he had apparently been working as a spy for the French. Several of his friends had been arrested; Lenglet had fled from England at the close of 1917 only because the police were after him. By marrying such a man, Rhys would be putting herself at grave risk.

The one thing Lancey seems to have chosen not to convey to his guest—perhaps he was unaware of Lenglet’s second marriage—was that her fiancé had a wife still living in Paris; perhaps, he thought enough had already been said. Rhys, to his astonishment, was undeterred. Risks, as she calmly reminded him, were what she most enjoyed. Didn’t he remember that she thrived on danger? “He gave a little nod.” Only after Lancey had gained her promise to stay in touch—and then kissed her goodbye—did she break down. Rhys wrote in her memoir that she went home in tears.

Danger did excite Rhys; Hugh Smith’s warnings were all ignored. In the spring of 1919, too overjoyed at the prospect of escaping from a country she had grown to detest to care about any possible mishaps, Jean Rhys set sail for the Netherlands—and the start of a new European life.

*“Triple Sec” includes a long confession by Suzy of her unworthiness to become “Ronald’s” wife.

†Most of the young islanders who enlisted were served up as cannon fodder. Dominica’s most respected modern historian argues that it was the British Army’s segregation of black recruits in the First World War which spawned the island’s first move towards independence in the early 1930s (Dr. Lennox Honychurch to author, 15 February 2019).

‡The same attractive lodger would feature as “Estelle” in “Till September Petronella.”

§In a later draft of “Leaving England” (a chapter in Smile Please), Rhys crossed out the word “sister” and bitterly substituted the phrase: “someone who didn’t care whether I lived or died.”