6

A Paris Marriage (1919–25)

“From 1917 onwards a gap. He seemed very prosperous when I met him in London, but now no money—nix. What happened? He doesn’t tell me.”

—Jean Rhys, Good Morning, Midnight, Part Three (1939)

ON 30 APRIL 1919, in front of two local witnesses at The Hague, Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams married Willem Johan Marie Lenglet (“of no fixed profession”). Lenglet saw no need to explain to his bride why the ceremony needed to be conducted outside France—where Rhys’s bridegroom remained the legal husband of the abandoned and presumably uncontacted Marie Pollart.

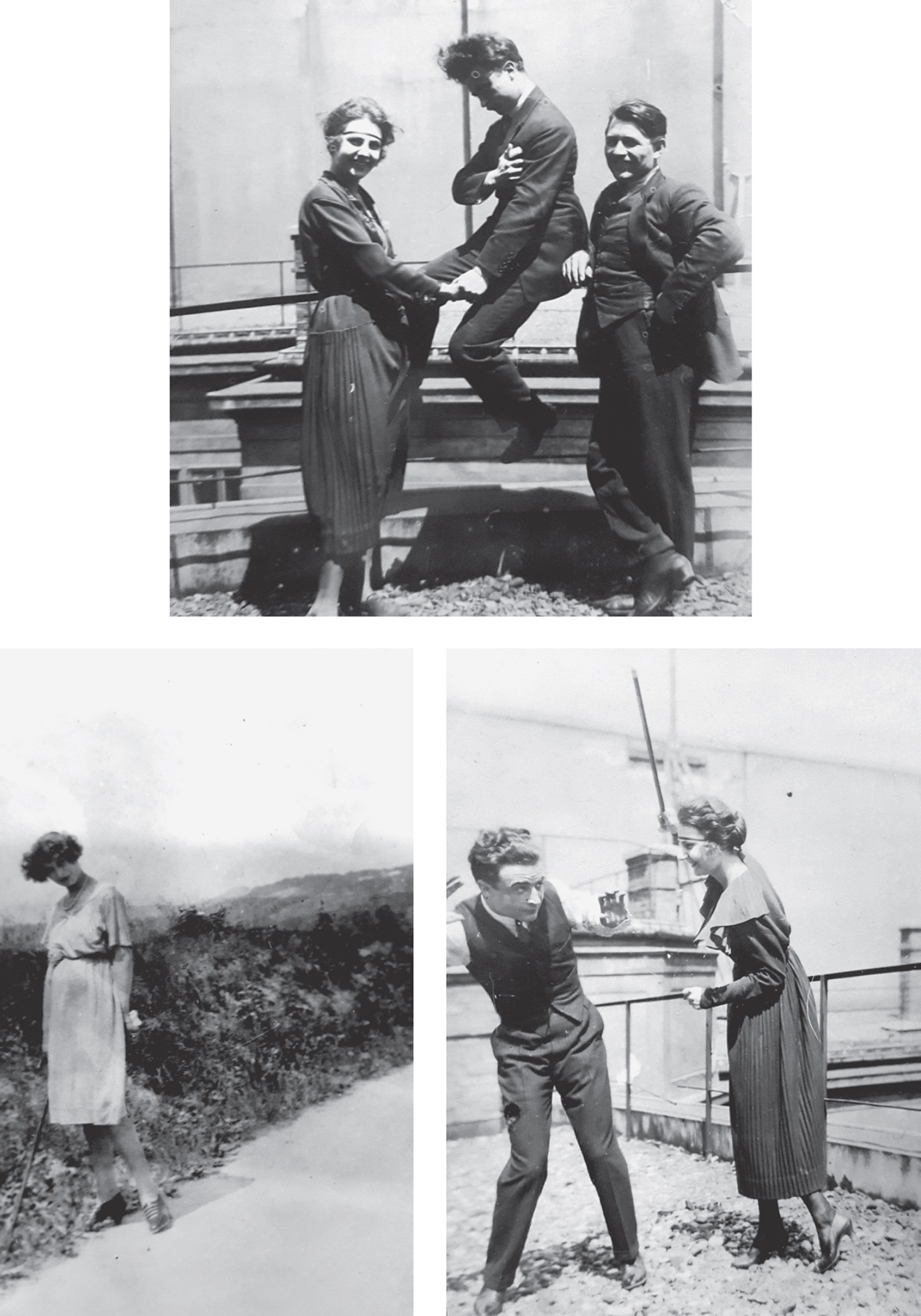

Knowing only that she had married a man who loved poetry, sang charmingly and with whom life always felt exciting, Jean Rhys was happy in the five months that she spent living with Lenglet in the pretty old town of The Hague. She kept the photographs that prove it; little black-and-white images showing the Lenglets larking about on Scheveningen Beach, together with a burly male friend. One snap shows a demure Rhys kneeling down in a neatly pleated skirt as she waits for Lenglet to place an imaginary crown on her head; in another, the couple pretend to be having a fight. They both look marvellously carefree.1 Before the Lenglets left for Paris—her longed-for Paris—Rhys knew that she was pregnant.

The news that her husband’s lack of a valid passport meant they would be entering France illegally came as a shock. In Good Morning, Midnight, for which Rhys would draw upon her early memories of The Hague, Sasha Jensen undertakes a similarly illicit journey, curled up like a cat on a third-class luggage rack in order to escape attention. (“I didn’t think it would be like this,” she sighs.) Recording her own journey in one of her coloured exercise books, Rhys would remember Lenglet’s insouciance and her own terror. How could they possibly escape being captured by patrolling guards? As always, her husband had the answer ready: “How? Just by walking over the frontier. By walking along the road between quiet rows of poplar trees at night. A quiet night with the moon up. Walking along until you get past the sentry & finding yourself in Dunkirk in the early morning and so tired so tired . . . And the fear. . . .”2

Marked by Jean in her old age as “Austria,” these happy snaps more convincingly belong to the Lenglets’ honeymoon months at The Hague, when Scheveningen beach was nearby. Their friend is unidentified. (McFarlin)

By early September, safely arrived in a Paris that had just liberated itself from the massive encircling stone walls erected in the previous century, the Lenglets had settled into a low-ceilinged fourth-floor hotel room on rue Lamartine, in the pleasant area south of Gare du Nord known—ever since the arrival of the flamboyant Palais Garnier—as Opéra. Today, still sporting an entrance door crowned by reclining nymphs, the Lenglets’ first French home has become part of the Hotel des Plumes, although Rhys’s name does not yet feature among the famous writers—Verlaine, Rimbaud, Wilde—proudly recorded in its brochure. An old-fashioned spiral staircase leads up to the couple’s snug home; beyond the bedroom window, overlooking a nineteenth-century école de filles, a hotel guest can still glimpse the narrow iron balcony on which the newlyweds used to drink white wine and smoke Jean’s favourite Egyptian cigarettes. The room itself was simply furnished (the largely fictitious Good Morning, Midnight provides the lovers with a large bed and a cosy red eiderdown), but it became a happy nest for two people who were very much in love. The Lenglets returned there whenever they could afford the hotel’s modest charges.

For Jean Rhys, born on an island where a creolised form of French was in daily use, Paris felt like a homecoming. She loved the pink glow of the long summer days and the subtler menace of the sea-blue dusks when tugboats whistled to each other along the Seine; she instinctively preferred the casual commerce of quiet neighbourhood bars to the noisy self-consciousness of the big brasseries of Montparnasse that were already being taken over by tourists from abroad. Each day, she revelled in her escape from the invisible social traps of London, a chillier, greyer city that had always seemed to Rhys to be intent upon crushing the spirit of a sensitive outsider.

Once, sitting alone in a boulevard cafe, an intrigued Rhys watched a Creole girl—“a lovely, vicious little thing”*—break away from her older, more sedate companions. “J’en ai marre” (I’m fed up), the girl shrilled as she whirled herself into a dance. Carelessly, she lifted her skirt: “Obviously the red dress was her only garment; obviously too, she was exquisite beneath it.” Delighting in how the girl strutted around to the song, listening to the seductive and familiar lilt of her island-bred voice, Rhys felt a moment of secret affinity. In London, she had struggled to repress her emotions in order to fit in. In Paris, she and this fiercely independent youngster had found their home.

The balcony of the Lenglets’ beloved attic bedroom in Paris on rue Lamartine. (Author picture)

Rhys’s time was not all her own. Shortly after arriving in Paris with her husband, she answered an advertisement in Le Figaro for a teacher of English to children. Asked to call at 3 rue Rabelais, just off the Champs Elysées, a mildly awed Rhys was ushered by a uniformed maid into the presence of a slight, dark-haired and smiling woman. She introduced herself as Germaine Richelot, unmarried aunt to the four little cousins with whom Madame Lenglet would be expected to converse only in English, a language with which the young Bragadirs and Lemierres were already familiar. Rhys’s acceptance was seemingly taken for granted; invited to stay for a family lunch, she was instantly welcomed as a friend, not an employee.

Rhys’s recollections of her three months working for the family of Dr. Louis Gustave Richelot, a respected figure in the French medical world, carry no barb or hint of discontent. Each day, she dined with the family in a room hung with beautiful tapestries and guarded by one of the doctor’s greatest treasures: a serene wooden Madonna. The mornings were reserved for English conversation with the children; during the afternoons, Germaine insisted that the pregnant “Ella” should rest herself in one of the Richelots’ favourite rooms, a light-filled studio. Sometimes, she heard Germaine’s musical sister, Yvonne Bragadir, practising for a concert off in some distant room, or softly chatting with the young women’s third sister, Jeanne Lemierre, the wife of an eminent physician who lived in a neighbouring street.3

Rhys liked and admired all the Richelot family, but it was Germaine who sought to become her particular friend. Germaine confided that she was a secret socialist. She longed to get rid of the family Daimler. Covertly, she attended political meetings. During the war, she had learned terrible things from her voluntary work as a marraine de guerre (a soldier’s correspondent and comforter). Germaine talked; Rhys, so it seems, was usually the listener in the intimate discussions that continued until, eight months into her pregnancy, the long daily trek from rue Lamartine became too demanding. Gratefully, Rhys promised to stay in touch, and always to consider herself one of the family. Since Dr. Richelot was a gynaecologist, it is to be supposed that this generous family helped to locate (and perhaps even paid the bills for) a hospital suitable for the birth of Rhys’s first child.

Born on 29 December 1919, William Owen Lenglet was proudly named—though not baptised, since Jean Lenglet did not believe in baptism—after Rhys’s late father, and after Owen, the brother closest in age to herself. Perhaps the attic bedroom at rue Lamartine was draughty; the baby caught pneumonia. On 19 January 1920, the Lenglets’ small son died, aged just three weeks, at a convent hospital in rue Denfert-Rochereau.

Later, recalling the tragedy in Smile Please with an undertow of self-reproach that no careful reader can ignore, Rhys wrote that she and Lenglet had been patching up a quarrel (about her desire to baptise her sick baby) by drinking champagne with a friend at the exact moment that their tiny son had died, alone. “We were all laughing,” she wrote. The nuns at the hospital had told her, when she asked, the precise hour of the baby’s death. “He was dying, or was already dead, while we were drinking champagne.”

Rhys could not forgive herself. She had not been there and she had let her little boy die bereft of proper religious rites. The convent sisters assured her that a baptism had taken place; how could she be certain that they weren’t simply consoling her? The baby was hastily buried at Bagnieux, just outside Paris. Privately, Rhys attempted some form of atonement by writing—the date is unknown—a poem which she named “Prayer to the Sun.”

A wistful short prayer to a higher power, Rhys’s unpublished and affectingly bleak little poem (it consists of fifteen short, unrhymed lines) refers to the loss of a child; a loss for which the poem’s author seeks absolution. The speaker is imprisoned within a coffin-like chamber. Poignant allusion is made to the absent consolation of trees, tranquillity, and running rivers. Outside the door, the city continues on its indifferent way; “alien voices” provide a remote background noise. Beginning and ending with a prayer for deliverance, the poem suggests that Rhys did not recover quickly from the death of her first-born child. She always initially wrote by hand, but this little poem has evidently been revised and typed out in what may have been a final form.4

A swift change of location was welcome at such a desolate moment; the Richelots stepped in to help by finding Monsieur Lenglet (whom they had never met) a lucrative position as interpreter for the Japanese section of the Inter-Allied Commission being hastily set up in devastated postwar Vienna. The job required the bereaved father to leave Paris at once; Rhys’s distraught state is apparent from the fact that, having found herself another English-speaking job to earn some money before following Lenglet to Vienna, she somehow managed, on her first day of employment, to lose her way from child-friendly Parc Monceau back to her pupil’s nearby home on avenue Wagram. That particular stroll takes a pedestrian less than three minutes; Rhys ended by dragging a weeping little boy halfway across Paris before flagging down a taxi to take them home. Refunded the fare by the child’s angry mother, Rhys was also sacked on the spot. A week or so later, Germaine waved her sad-faced friend off on the train to Vienna.

THE LENGLETS, PARTLY due to some quiet currency trading of the sort that became common after the war, now grew rich. The citizens of “Red Vienna,” so named for its vigorous new postwar policy of social reform, were starving; Rhys, for once, was on the winning side. While the Japanese officers took up residence at Sacher’s Hotel, the Lenglets and their friend “André” (Rhys’s pseudonym for a romantic young French bachelor regarded as the Inter-Allied Commission’s wild card), moved into the Imperial, after lodging with a family of Austrian aristocrats who had lost everything but their grand address on the elegant Favoritenstrasse. You could always tell what a lady Madame de Heuske was, Rhys would confess with self-damning insouciance, from “the faraway look” with which she complied with Madame Lenglet’s request for a restorative personal massage of her back and chest.5 The hypersensitive Rhys was conscious of an implied criticism of herself in the fact that the de Heuskes forbade their daughter Blanca to apply cosmetics to her own fine, transparent skin. Rhys, by contrast, dyed her hair red and paid weekly visits to a beautician. Passers-by, so she would sardonically recall, sometimes compared her to a doll made from the purest white Saxon china (“la poupée de porcelaine de saxe”).

“Funny how it’s slipped away, Vienna,” Rhys would ruminate in the marvellous short story “Vienne,” which she would write during the next few years. Living in a world that placed a high value on looks, Rhys lingered on the extraordinary beauty of a Viennese dancer coveted by the city’s visiting officers, who nevertheless fear that she may be “too expensive.”

A fragile child’s body, a fluff of black skirt ending far above the knee. Silver straps over that beautiful back, the wonderful legs in black stockings and little satin shoes, short hair, cheeky little face . . . Ugly humanity, I’d always thought. I saw people differently afterwards—because for once I’d met sheer loveliness with a flame inside . . . Finally she disappeared. Went back to Budapest where afterwards we heard of her . . . Married to a barber. Rum.6

For the dancing girls, as Rhys was quick to recognise in a passage that suggests the influence of Colette on her early work, the visiting officers represented only money; a way out of poverty. For Rhys herself, the city offered an escape from the swift and painfully remembered death of her baby son. “Vienne” describes 1920 as a time when “Frances” (or “Francine”) feels “cracky with joy in life”; a later and far more elaborately constructed story titled “Temps Perdi” catalogues every one of the ravishing dresses that a newly rich Lenglet had personally selected for his wife’s Austrian wardrobe. Ruffled white muslins; rustling organzas; brilliantly coloured prints in cornflower blue and buttercup gold: all that Rhys would omit from that loving retrospective inventory was a magnificent astrakhan coat, purchased to keep out the bitter cold of Viennese winters. The coat from Vienna would haunt the future novels of Jean Rhys as a symbol of bad times (when it went to the pawn shop) and adventurous times (when it cloaked what Rhys once privately and savagely described as her treacherous body’s “little trot” along the sidewalk, nostrils flared, picking up the scent of sex in the spring air: “Trust me, trust me, says the body—But trust it, never.”7)

The Inter-Allied Commission remained in Vienna for over a year. On Rhys’s thirtieth birthday, the Japanese officers held a splendid dinner in honour of “Ella et Jean,” from which she preserved an autographed menu card, one which would earn a brief mention from Julia Martin in Rhys’s second novel. The city enchanted Rhys; she was disappointed to learn in 1921 that it was time for the commission to move on to Budapest where—following two waves of terror, during which many Hungarians had fled abroad—a regent, Miklós Horthy, had replaced an exiled king.

Rhys in Vienna, wearing what may have been the famous fur coat which would feature in her novels, where it sometimes acquired an astrakhan collar. (McFarlin)

As with Vienna, Rhys experienced Budapest from within a cocoon of wealth. Jean Lenglet had profited handsomely from his currency transactions back in Vienna. Rhys kept a photograph of the couple’s Austro-Daimler with their uniformed chauffeur chubbily ensconced behind the wheel; it was—did the thought ever cross her mind?—precisely the kind of car that Germaine Richelot despised.

It is likely that the Lenglets were housed in Pest, the livelier of the yoked cities that confront each other across the Danube; certainly, they felt at home in a shadily romantic city crowded with leafy little squares and Parisian-style cafes. The Hungarian women were beautiful, but none were lovelier—as doubtless Lenglet reassured his wife—than her own petted and cherished self. It may have been a desire to flaunt that shapely, well-dressed body before the sceptical Lancey Hugh Smith that caused Ella Lenglet, during the late summer of 1921, to make an impulsive brief visit to London.

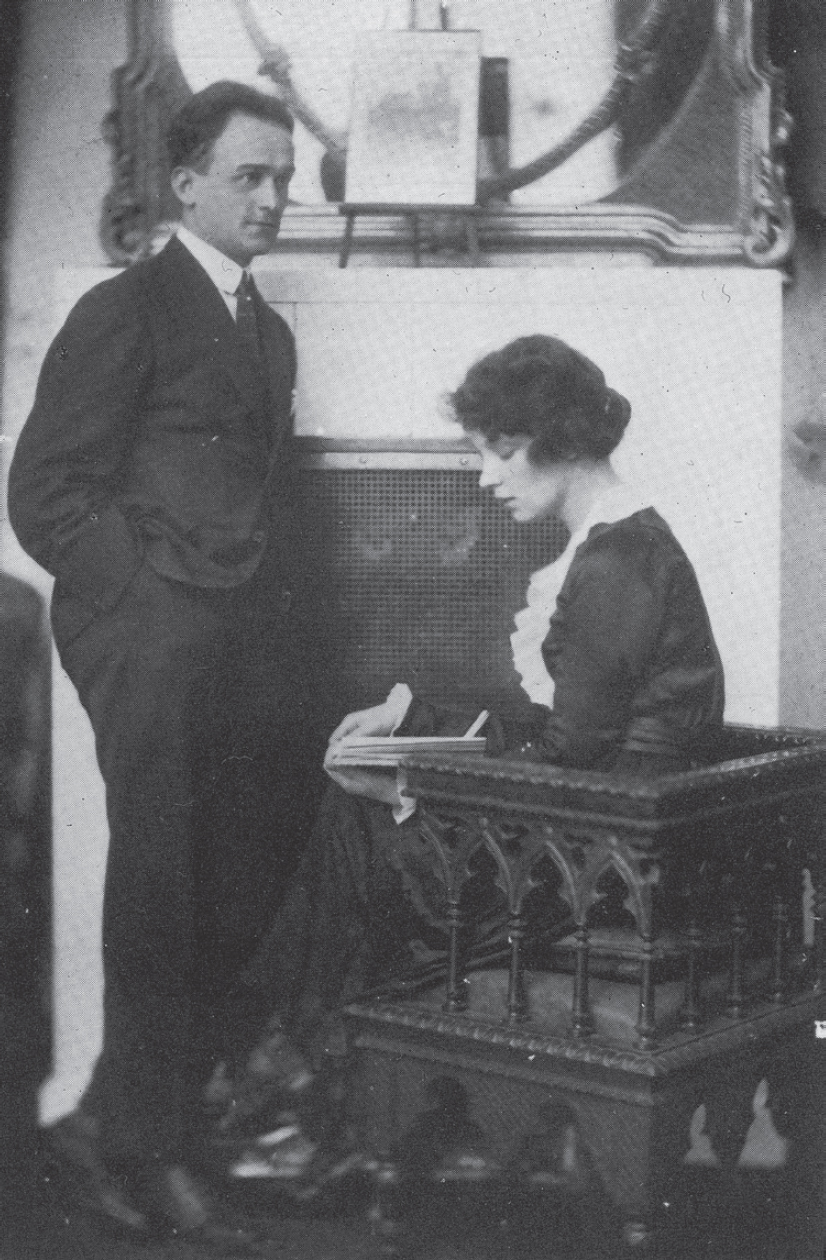

The Lenglets at home during their year with the Inter-Allied Commission in Vienna and Budapest. (McFarlin)

The conjecture that Rhys was seizing an opportunity to parade her successful marriage to a mistrustful former lover is prompted by her choice of hotel. The Berkeley stood within spitting distance of Lancey’s own discreet abode in Charles Street: the home in which a conventional man had never permitted his young mistress to spend a single night. It’s unlikely that Rhys was invited to do so now. The friendship survived, but their affair was over.

Rhys may also have been summoned to London by a needy family. Following the death of Dr. Rees Williams, his widow had fallen on hard times in Dominica. By the summer of 1921, there were no white Lockharts left on the island. Proud Minna, having grown up in the Great House at Geneva, was living in cramped conditions at 28 Woodgrange Avenue in Acton, west London. Crowded in beneath the same gabled roof were Minna’s unmarried twin, their widowed sister, two daughters and a devoted nurse companion called Miss Woolgar. By 1921, Jean Rhys’s mother had already become bedridden; by 1927, the year in which she died, a series of strokes had rendered Minna Rees Williams unable to communicate, or even to sign her own name.

The account of an awkward family reunion which Rhys would put into her second novel, After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, appears to draw upon and combine two separate visits to Acton, of which this was the first. Grudgingly conscious of her younger sister’s stoic heroism, Julia Martin compares Norah Griffiths to a character in an unidentified Russian tragedy, “moving, dark, tranquil, and beautiful, across a background of yellowish snow.” Entering the bedroom in which her mother now lies prostrate, every day, all day long, Julia imagines that she has attracted a flicker of recognition: “Then it was like seeing a spark go out and the eyes were again bloodshot, animal eyes.”8

Rhys’s description of Julia Martin’s cool reception by her family at Acton may only slightly exaggerate the contempt with which selfish, well-dressed “Gwen” was received by an impoverished family of reluctant exiles. Julia, however, is broke and importunate. Rhys, in 1921, was riding high.

Back in Budapest for her third autumn out of England, Rhys discovered that she was once again pregnant. Shortly afterwards, Lenglet confessed that he had gambled and lost a small fortune embezzled from his superiors in the commission. Now, penniless and terrified of arrest, he was ready to kill himself.

In life, as in the short story “Vienne” that she would soon base upon her continental adventures, Rhys took pride in her cool-headed behaviour in times of crisis.† Loyal Lancey would never let his erring kitten down: “My plan of going to London to borrow money was already complete in my head,” Rhys makes “Francine” say in “Vienne.” “One thinks quickly sometimes.” The need to escape from Budapest was imperative—but not before a last celebration. Like Lenglet, perhaps, “Pierre” in “Vienne” orders a last, splendidly ostentatious bedroom dinner of wild duck and two bottles of champagne; touching Pierre’s arm as if to draw his newfound bravado into herself, Francine feels her own courage wane. “Horrible to feel that henceforth and for ever one would live with the huge machine of law, order, respectability against one. Horrible to be certain that one was not strong enough to face it.”9

Preparing to leave London for The Hague, back in the early spring of 1919, Rhys had boasted to prudent Lancey that she revelled in taking risks. Fleeing from Hungary in 1921 in the Daimler driven by their stolid chauffeur, her relish for danger was put to the test. “Vienne” fictionalises a frightening moment in the Lenglets’ flight at the Czech border, where Pierre is taken into a patrol hut for interrogation. Emerging at last, he shouts to the chauffeur to get moving. “The car jumped forward like a spurred horse,” Rhys recalled in her story. “I imagined for one thrilling moment that we would be fired on . . .” On they flew, towards Prague—and then off again.

“Faster! Faster! Make the damn thing go!”

We were doing a hundred . . .

“Get on! . . . Get on! . . .”

We slowed up.

“You’re drunk, Frances,” said Pierre severely.10

“Vienne” ends breathlessly in November 1921 outside Prague, on the verge of a last flight to England (“It was: Nach London!”). At this point, Rhys’s private life vanishes from view until the birth, on 22 May 1922, of Maryvonne Lenglet, in Ukkel, Belgium. By July, following a further request to Lancey for help and a subsequent seaside holiday at Knokke-sur-mer, the vagabonds were safely back in their attic room at the little hotel on rue Lamartine. This was no place in which to bring up a child. Helped by Germaine Richelot, the Lenglets reluctantly arranged for Maryvonne to be cared for at a series of baby shelters or orphanages (each bore some saccharine name like “The Cradle”), from which she could be whisked back home at whim. This seemingly heartless practice was not uncommon. By 1922, two years before he encountered Jean Rhys in Paris, the English novelist Ford Madox Ford had deposited his adored baby daughter by Stella Bowen in a damp little cottage on the edge of the city, where Julie was cared for by a nurse while her unmarried parents resided in Montparnasse.

In the autumn of 1922, a further catastrophe struck the Lenglets when the French police showed up at rue Lamartine, demanding Lenglet’s immediate return to his lawful wife. Loyal though Rhys would remain to a husband who seemed habitually to live on the wrong side of the law, the revelation of his bigamy marked the beginning of an erosion of trust from which the couple’s relationship would never entirely recover. Over the next two years, Lenglet occupied the twilight world of a fugitive, one from which he would sporadically emerge and seek Rhys out; essentially, she faced life alone.

Other than the saintly Richelots and an occasional handout from Lancey (with whom she remained in irregular contact until at least 1925), Rhys now had no resources. Her story “Hunger” dryly reports the number of days—five—for which a young woman in similar circumstances can survive on bread and coffee.

“Hunger” and the three bitter stories which follow it in The Left Bank, Rhys’s first published collection, may well be based upon actual memories of this challenging period. In the first of the three, the narrator withholds her pity from a starving friend who not only continues to rouge her lips and to wear silk stockings, but dares to be flippant about it. (“What did you say?” the narrator asks before repeating the starving woman’s retort in dull disbelief: “. . . You cannot buy special clothes to starve in. Naturally not.”) In the next, “A Night,” where the (once again) penniless narrator wonders whether a lover’s tenderness might be enough to keep her from killing herself by drowning or gunshot, Rhys uses the speaker to voice the nonspecific hatred which will become a feature of her work: “It is as if something in me is shivering right away from humanity. Their eyes are mean and cruel.” In the third and least successful, “In the Rue de l’Arrivée,” a stony-broke and slightly drunk Englishwoman learns to accept pity from someone even unluckier than herself. “Pauvre petite, va,” murmurs the sinister-looking man who might have been about to pick her up or murder her, after he catches sight of her face. That night, in Miss Dorothy Dufreyne’s troubled dreams, the same stranger returns disguised as an angel, about to carry her off to hell: “But what if it were heaven when one got there?” Sentiment still smudges the sharp edges of Rhys’s prose, but here, very faintly apparent, are the first traces of Rhys’s fourth and finest novel, Good Morning, Midnight.

How did Jean Rhys survive two years—autumn 1922 to the autumn of 1924—of poverty and unwelcome independence? The wealth that Lenglet had accrued in Vienna and Budapest had vanished, leaving only a cupboard filled with exquisite clothes to inspire “Illusion,” one of Rhys’s most whimsical early stories (about an outwardly dowdy English woman whose Parisian wardrobe is filled with improbably exotic dresses that include “a carnival costume complete with mask”). Scraps of paper surviving from that bleak period bear the names of various Paris hotels, often in grim areas like the then-notorious wasteland of Place Dauphine. Did Rhys prefer to hole up in some hideaway where she could read and write, to begging from the small group of expatriate friends who had known her in London, before the war? Was this the time when she began to read Colette (for whose early books about the great novelist’s years in vaudeville Rhys would retain an enduring admiration) and the remarkable Pierre Mac Orlan, whose stylistically brilliant and often witty Parisian novel about a modern-day Faust and a pure-hearted prostitute, Marguerite de la Nuit (1924), became one of her most cherished volumes?

Rhys’s only known employer during a period of daunting challenges (met with characteristic defiance) was Violet Dreschfeld, a Jewish sculptor living in Paris. In Quartet, Rhys’s first and most directly autobiographical novel, Dreschfeld is represented by the gauntly anxious Esther de Solla; in After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, a similar character called Ruth owns a Modigliani print—a tigerish, lounging nude with which Julia Martin feels a troubled affinity. Esther and Ruth are mature women, but Violet was close in age to Rhys herself. Their personal relationship is unclear, but Rhys—who would preserve almost no souvenirs from this period of her life—did keep one small photographic record of Violet’s work; it presents a modestly dressed “Ella” seated on a rock, her head bowed in thought. Dreschfeld never married and seems to have formed no other significant relationships. We can’t know whether she became Rhys’s lover for a time, or simply provided a bit of badly needed income, or both. Rhys’s relationships with women remain one of her best-kept secrets, but she writes about the female body with an appreciation of physical beauty that seems to go well beyond self-regard.

IT WAS DURING the last quarter of 1924 that a dramatic change occurred in Rhys’s life. Lenglet had managed to rejoin her in Paris. Money remained desperately short. It was her own idea (or so Rhys would recall in Smile Please) to turn her husband’s colourful past to commercial use. Lenglet had worked both as a journalist and a singer in his prewar life; Mac Orlan had written about his own experiences as a chanteur at Le Lapin Agile; surely it wouldn’t take her husband long to dash off a few racy vignettes about his nights as a teenage heartthrob at Montmartre’s famous club? Lenglet complied. Theirs would always be an affectionately collaborative partnership where writing was concerned; after translating and sharpening her husband’s submissions, Rhys took them along to the offices of the Continental Daily Mail. Courteously informed that Lenglet’s anecdotal pieces were a bit old-fashioned for the Mail’s readers, Rhys rejected the compensatory offer made to herself on the spot to become an interviewer of celebrities, working from the paper’s office in Rome.

In Rhys’s retrospective account of the sequence of events, it was an editor at the Daily Mail who then suggested that she might show her husband’s stories to Helen Pearl Adam, an American journalist whose husband had previously worked in London alongside Maxwell Macartney at The Times. “I was very nervous as I’d only met Mrs Adam once,” Rhys would write in Smile Please, “and I wondered if she’d remember me.”11 Pearl was already aware of Rhys’s ambitions as a writer, however; she may even have been told about a work in progress. And so, having rejected Lenglet’s anecdotes, Adam apparently asked to see something written by Rhys herself. Playing her cards with care, and conscious of the urgent need to show something marketable to a seasoned journalist, Rhys held back the accomplished stories that she had been working on in Paris during Lenglet’s long absences. Instead, she handed over the raunchier and still unnamed episodic novel that had started life in Chelsea in a handful of large-sized notebooks, a year before the war.

Pearl Adam liked what she read, enough so to offer to edit the material and give it a catchy title. “Suzy Tells” would offer a knowing nod both to one of Paris’s best-known drinks (a “Suze Fine” was Pernod-based) and to Suzy’s, a famous brothel that was celebrated later by the photographer Brassaï.

What happened next would change Rhys’s life. Having divided “Suzy Tells” into sections, each headed by a man’s name, Pearl Adam decided that Rhys’s scandalous manuscript was original enough to interest Ford Madox Ford, editor of Paris’s respected literary magazine for English-speaking expatriates, the transatlantic review. She was right; Ford was intrigued. Nevertheless, a few days after reading “Suzy Tells” and then renaming it “Triple Sec,” Ford set the typescript aside. Instead, he told Pearl Adam that he wanted to see more of this writer’s work. Moreover, he wanted to meet such a gifted young author in person.

*“Vicious” is used here in its French sense, vicieuse, meaning depraved, amoral (Jean Rhys, “Trio,” 1927, in Collected Short Stories, Penguin).

†The autobiographical nature of “Vienne” is confirmed by the fact that the protagonists were initially named “Ella” and “Jean.”