13

Beckenham Blues (1946–50)

“If the law says you’re dangerous, you’re dangerous. If the law says you’re mad, you’re mad. Then God help me.”

—Jean Rhys, Orange Exercise Book, c.19501

FEW COUSINS CAN have had less in common than Leslie Tilden Smith and Max Hamer. Leslie was bookish and—except when he got drunk and quarrelled with his wife—quiet; Max was outspoken, exuberant and—when he first met the widowed Rhys—unashamedly indifferent to culture. A good raconteur in possession of a pack of yarns, he regaled Rhys with comic stories about the early years he had spent at sea before his embarkation (following a decade of unemployment) on a less adventurous career as a trainee solicitor. It was probably Max’s employers who had encouraged a somewhat imprudent man in his mid-fifties, equipped with a wife and young daughter, to invest in property. And so, at some point between 1930 and 1938, Max Hamer took out a mortgage in order to purchase a three-storey gabled Victorian house in the new south London borough of Beckenham, formerly a village in Kent. Plans to move there were forestalled by war: Beckenham lay on “Doodlebug Alley,” a firm favourite with the Luftwaffe.

Like Leslie, Max had signed up once again, despite his mature years, to do his bit against Hitler. (Max was eight years older than Rhys, although he may never have known it.) In 1945, the sixty-three-year-old Lieutenant Commander Hamer’s impressive title concealed a humdrum job supervising the issue of barrage balloons and kites from HMS Aeolus, a warehouse staidly anchored behind the high street of Tring, in Hertfordshire.

Rhys’s third husband, Max Hamer (pronounced “Hay-mer”), was a cousin of Leslie Tilden Smith, a roguish charmer who made Rhys laugh. (McFarlin)

The attraction of Max as a potential husband—he was not forgiven by his wife of over thirty years for starting divorce proceedings shortly after he met Rhys—was considerable. Dapper, funny and well spoken, he was a far more sexual man than Leslie. On a more practical level, he owned a house; Rhys, when her sister-in-law ceased to pay the rent at Steele’s Road, was going to be without a home. But what a shy, introverted woman, one who was prone to despair and self-doubt, valued above all in Max Hamer was his unquenchable cheeriness. He made her happy.

Max’s optimistic temperament meant a lot to Rhys in 1946, the year in which she turned fifty-six. The end of war had ushered in a period of continued rationing and relentless hardship for most of the British population, half a million of whom lost their uninsured homes to bombing raids. Rhys’s own spirits were not lifted by the difficult task of revising her wartime stories, among the darkest that she would ever write. Pushing herself even harder, she was determined to create a fictional record of the mysterious portents that had preceded Leslie’s sudden death.

Writing “The Sound of the River” so soon after the loss of her husband brought Rhys close to a complete breakdown: she told Peggy Kirkaldy that she couldn’t even bear to listen to certain music or to read her favourite French poets. She believed this story to be among her best work. She showed her faith by insisting that “The Sound of the River” should provide the title for the short and stark collection that she proudly submitted in March 1946 to Michael Sadleir of Constable. “It’s been the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Rhys had admitted to Peggy in February. By July, the publisher had turned it down, and hope had fled. “No one does believe in me,” she sadly wrote.2

Sadleir’s response was dismaying, but understandable. Having already been burned by the poor reception and negligible sales for Good Morning, Midnight, he shunned the patent risk of publishing an even more disquieting production, and in bleaker times. In 1946, English book-buyers wanted entertainment, not anguish. Crime fiction sold well (Sadleir’s own historical thriller, Fanny by Gaslight, had recently been filmed); war-weary readers lapped up the romantic novels being written by Georgette Heyer and Daphne du Maurier. How could Jean Rhys’s savage vision of a country at war, observed by her group of vociferously unpatriotic outsiders, hope to match the sales of Elizabeth Goodge’s sweetly fantastic The Little White Horse, or even Nancy Mitford’s acidly funny portrait of the declining ruling class at play, The Pursuit of Love?

Widowhood; lack of money; rejection; the encroaching spectre of old age: for all these reasons, an always reckless woman embraced the comforting attentions of a sensual, entertaining and delightfully hopeful man. Job Moerman, preoccupied by his postwar work with British intelligence—he would spend the following year back in the Netherlands, teaching the art of information-gathering to army officers stationed at Breda—didn’t have time to fret over why a singularly well-read novelist was living with a man who shared none of her intellectual curiosity.3 (Rhys had begun the year by lending Peggy a smuggled copy of Tropic of Cancer, while begging for its return.) Reporting back to a relieved Maryvonne, Job merely said that Rhys—still always referred to as Ella by her family—seemed in good heart.

Max asked Jean to marry him even before he became free; Rhys bridged an awkward hiatus by changing her legal name to Hamer by deed poll. By the time her third marriage took place on 2 October 1947 (two years to the day after Leslie’s death, and just two weeks after Max obtained a divorce involving substantial alimony payments), Rhys had already exchanged her flat on Steele’s Road for life on the breezier heights of Beckenham.

BACK IN THE 1940s, the proud new borough of Beckenham was an exceptionally decorous suburb. Civic parades were opened by sensibly shod ladies with large hats and double-barrelled names; the local tennis club and sports grounds, sponsored by Beckenham’s sturdy new row of provincial banks, were well attended. So was the old grey church of St. George’s, which stood guard high above Beckenham’s winding hillside high street. No church-goer herself, Mrs. Hamer’s preferred weekly appointment was with the local hairdresser to whom she repaired for a shampoo and set whenever a disquietingly flirtatious husband seemed about to stray.

The trouble with Max, as Jean later explained to Peggy Kirkaldy, was that while she herself might often “look potty, he is potty.”4 Evidence of her partner’s unreliability became apparent as soon as they moved into 35 Southend Road. The house itself was large but damp; a rickety iron balcony overlooked the fruit trees and brambles in a small, neglected garden at the back. A cavernous cellar had become a wartime home to an army of rats, while the cast-iron water pipes were rusted beyond use. A builder selected by Max for his friendly manner requested a down-payment of £400 in cash (£15,000 today) and promptly disappeared. Max’s postwar return to work as a solicitor had been short-lived. Newly unemployed, he decided to raise money by joining forces with a well-spoken former jailbird who urged Max to take a punt on nightclubs. Such a speculative investment naturally required many evenings of careful research; Rhys was left at home, alone. “Clinging vines aren’t in it,” she later sighed to Peggy when reviewing her passive acceptance of her fate.5

Rhys wasn’t drinking much during her first months at Beckenham. The chief consolations of an often solitary life were her cherished collection of English, French and Russian books, her writing (however unpublishable) and the company of her three cats. Black-coated Mr. Wu was a sleek and fiercely handsome fellow, closely followed in his mistress’s affections by pretty Gaby and, lastly, Mi-Kat, a keen mouser who kept the cellar rats at bay. When the next-door couple’s guard dog killed both Mr. Wu and Gaby, Jean reacted with predictable fury. Summoned to Bromley magistrates’ court in April 1948, she was charged with throwing a brick through her neighbours’ window and threatening to do so again.6 Found guilty of having wantonly destroyed an apparently historic piece of stained window-glass, Rhys was ordered to pay £5 (£175 today) compensation to Mrs. Hardiman, proud wife of a respected shoemaker and a figure of conscious importance in Beckenham society.

Characteristically, Jean Rhys would soon put her legal defeat to good use: Selina Davis, a free-spirited mixed-race woman living in Notting Hill, is found guilty of precisely the same crime in one of Rhys’s best-known postwar stories, “Let Them Call It Jazz.” At the time, however, Jean simply retreated behind a set of newly ordered Venetian blinds, which she kept pulled down all day. Screened windows only provoked further suspicion; from April, until the day of her ultimate departure from Southend Road, Mrs. Hamer was kept under close scrutiny by the local residents.

Larger worries than dead cats or hostile neighbours were preying upon Jean’s mind in the summer of 1948. Maryvonne, bringing along her baby girl for a first visit to Southend Road, broke to her dismayed mother the news that the two of them, accompanied by Hock, their pet chow, were about to follow Job out to Java. Born in Indonesia, Job Moerman had gained a position as clerk to the largest Dutch shipping line in the East Indies. The post was a risky one since it was offered at a time when Indonesia was seeking to assert independence from the Dutch empire, and when armed combat was threatened. Maryvonne did her best to make light of the potential danger. Nevertheless, having so recently become accustomed to the fact that her daughter was still alive and well, Jean grew anxious. Six months later, while making light of friction with her Beckenham neighbours (the court case went unmentioned), she apologised to Maryvonne for having been so poor a mother, one who had never “helped you enough or been the right sort of person for you.”7

WRITING TO PEGGY KIRKALDY in 1950 about her unhappy life at Beckenham, Rhys explained that it was then, when she went “all of a doodah,” that she had once again started to drink.8

One theory about Jean Rhys’s hard-drinking habit holds that it was driven by her body’s need for a sugar boost; Rhys’s granddaughter, Dr. Ellen Moerman, points to the fact that her own mother, during her later life, was diagnosed with diabetes.9 While it’s true that Rhys favoured sugar-laden drinks and often drank sweet wine early in the day, an unidentified diabetic condition would have made it unlikely for her to go at times for several months without a drink, while betraying no signs of ill health or unusual lassitude. In calmer periods, Jean was often happy only to sip a glass or two of wine at supper and exhibited no ill effects; when anxious or unhappy, alcohol comforted Rhys and she drank fast, in order to get drunk. Despite the pride she always showed in having a strong head, it never took long.

By the end of her first year at Beckenham, Rhys needed the comfort of drink to blot out her worry about Maryvonne, out in the East Indies, and to deal with the grim realisation that her hopeful, gullible Max was an easy target for any silver-tongued crook whom he happened to meet. By the autumn of 1948, she was threatening to leave him; instead, Max made a surprisingly practical suggestion. The house on Southend Road was built for family use; why not raise revenue without risk by renting out the underused upper floors? Two couples, the Bezants and the Daniells, moved in during November. Recent Jewish emigrants, the new tenants may already have been friends when they arrived at Southend Road; if not, they certainly became so during their stay. An in-house alliance of refugees from Germany boded less than well for a temperamental landlady who had already been cautioned in Norfolk for saluting Hitler.

The comforting prospect of a steady rental income was offset for Rhys by the news that her enterprising husband had discovered a new route to prosperity. The source was to be a certain Mr. Roberts, an inventor whose plans required investment in the form of substantial loans from his new partner. More reassuringly, Max found himself a day job in March 1949, working as managing clerk for a family firm of solicitors. Cohen & Cohen were an unusual outfit (the father lived at a hotel on Park Lane, while his playboy son preferred chasing women to pursuing legal cases) and Max’s work proved undemanding. Unfortunately, his new annual salary of £400 attracted the keen interest of Mr. Roberts, a man who, like Max’s previous business partner, preferred to do business after hours. Left alone all day and for a great many evenings, Rhys continued with her project for a prequel to Jane Eyre, with Bertha Mason as the central character. In the spring of 1949, she planned to locate “The First Mrs Rochester” (as Rhys now named the reworked “Revenant”) at the ultra-English naval port that she had already used for a discarded historical screenplay set on Antigua and titled “English Harbour.” The period in which to set her “West Indian” story remained unsettled; in October 1949, Rhys told Peggy Kirkaldy that she was considering placing “a novel half done” in the 1780s. The rest, she believed, was “safely in my head.”10

Work never calmed Rhys; in the spring of 1949, she was still worried about Mr. Roberts’ money-making schemes and terrified by the dangers to which Maryvonne, and her year-old granddaughter, might be exposed in politically turbulent postwar Java. She was already drinking heavily when her first serious confrontation took place with the upstairs tenants. The fault was largely Jean’s own: writing a long confessional letter to Peggy Kirkaldy, she later admitted “I couldn’t have behaved worse or with less tact.”11

The trigger seems to have been an evening party held in the Bezants’ flat on 11 April, in rooms just above where Rhys was trying to write, despite a racket which distracted, irritated and finally maddened her. The guests left an hour before midnight. A few minutes later, Rhys stormed up the stairs, shouted at Mrs. Bezant and then slapped—or perhaps punched—her husband. When the angry couple called in the police, as the tenants were always quick to do when she flared up, Rhys rashly called the constable “a dirty Jew.” After hitting and even biting him, she accused the bewildered officer of belonging to the Gestapo.*

Max, a former solicitor, represented his wife at her second appearance in Bromley magistrates’ court on 25 April. (Rhys had been bailed after pleading not guilty at the first.) A fair-minded magistrate awarded £3 to the injured policeman and a pound to Mr. Bezant. Mrs. Hamer was put on warning to keep the peace for a year.

Peace lasted less than a day. Back at Southend Road after her trial (Max had gone straight from the courtroom to the Cohens’ city office), Jean found that she had locked herself out of the house. A helpful policeman fetched her a plank of wood, via which she managed to clamber in through an open window, but not before taking a tumble. Humiliated, bruised and distressed by her morning at court, Rhys found herself confronted by all four of her tenants. A golden opportunity to point out that Mrs. Hamer’s saviour had been a member of the very constabulary she had recently abused was doubtless seized. The result was that Jean flew at Mr. Bezant.

Back in court on 6 May 1949, Rhys again pleaded not guilty. A claim that she had attacked Mrs. Bezant and Mrs. Daniell was briskly dismissed; the charge of an assault on Mr. Bezant was allowed to stand. As with the magistrate on the occasion of her wartime summons in Norfolk, the prosecuting council sympathised with the gentle, well-spoken lady in the dock. Agreement was swiftly reached that a token fine would be paid and that a psychiatrist would provide, at the end of three weeks, his assessment of the defendant.

On 27 May, Mr. Bezant appeared in court to declare that he had heard “nothing but screaming, shouting and abuse four times a week from this woman.”12 A warrant was served in her absence for Mrs. Hamer’s arrest. On 24 June, Max informed the court that his wife was not well enough to undertake the ten-minute bus journey to Bromley. Three days later, having finally complied with the psychiatrist after over a month’s delay, Mrs. Hamer showed up at the gloomy red-brick court building in person. It sounds as though Rhys had primed herself for the ordeal with a drink. “He [the magistrate] asked me if I had anything to say,” Jean later told Peggy Kirkaldy. “So I said it.” Having begun by objecting to being called hysterical by the psychiatrist, she found herself unable to stop. (“I hear myself talking loud and I see my hands wave in the air,” Selina says in “Let Them Call It Jazz.”)13 Rhys was finally silenced by the magistrate who abruptly sentenced her to five days in Holloway prison’s hospital wing, pending two years on probation and a further medical report. It’s unclear whether Max was present to see his sobbing wife led out of court and taken away in a black police wagon.

RHYS ENTERED HOLLOWAY through what appeared to be the gatehouse of a fortified castle; above the smoke-blackened archway, an inscribed motto prayed to God that “this place be a terror to evil doers.” Her experiences as a prisoner provided first-hand material for “Black Castle” (later retitled “Let Them Call It Jazz”), the story which Rhys began to write soon after her release. Her talismanic cosmetics and jewellery were removed; her clothes and shoes were replaced by flat brogues and a loose black tunic that distinguished the prisoners from the trimly pinafored female guards.

Being sent to prison was a terrible humiliation, but Rhys was not cruelly treated and the wing reserved for mentally and physically sick inmates was situated far away from Holloway’s “lifers”—although not far enough to block out the sobs and shrieks that haunted a newcomer’s nights. The dreariness of a postwar prison diet was compensated for by the opportunity to read—Rhys had learned the value of prison libraries from Lenglet—and, curiously, to rest.

Rhys got on well with the prisoners whom she met in Holloway. A cheerful old lag introduced her to the art of collecting “doggins” (the “dog-ends” or stubs of discarded cigarettes) and reminisced about her former life outside in “the Smoke.” A seasoned younger inmate advised Rhys to say as little as possible about herself to the woman doctor in charge of her case. Like Selina in her short story, Jean seems to have heeded a prudent warning.

It was the misery that got under Rhys’s skin during her stay at Holloway. “But oh Lord why wasn’t the place bombed?” she wrote that autumn to Peggy Kirkaldy: “If you could see the unfortunate prisoners crawling about like half-dead flies you’d understand how I feel. I did think about the Suffragettes. Result of all their sacrifices? The woman doctor!!! Really human effort is futile.”14

Selina contemplates killing herself by jumping off a high wall into the prison’s drill ground. If Rhys had similar thoughts, she suppressed them. Writing to Maryvonne on 10 July, during the week that she was pronounced sane and fit for release (although in prescribed need, for two years, of psychiatric observation), Jean mentioned only that she had been briefly in hospital. Brightly, she wrote of sitting out with Max on their little iron balcony and of picking fruit and berries in the neglected back garden. If Maryvonne was puzzled by her mother’s insistent tone when Rhys wrote on 16 August 1949 that “I am all right dear,” heavily underlining her words of reassurance, there was nothing that a faraway daughter could do.

The shock and disgrace of imprisonment had been too great for a brief summer jaunt out of town to raise Rhys’s spirits. Writing to Peggy on 4 October, Rhys confessed that she had temporarily lost the will to write. To Maryvonne, she had already confided her fears about Max’s most recent friend, a man who was promising him “heaven and earth.”15 Max, unknowingly, had met his nemesis.

WHAT MICHAEL DONN lacked in integrity—and it would seem that he had none—was masked by an abundance of charm. Young, charismatic and unscrupulous, he had no difficulty in persuading the gullible Max Hamer to find him a job with Cohen & Cohen. Convinced by his personable manner, the family lawyers took him on. Rhys, to her credit, was never deluded for a second about Michael Donn’s criminal streak, but Max started to behave with increasing recklessness, disappearing to Paris with Donn for five days before returning home via Jean’s bedroom window, late at night. Maryvonne heard that Max was “very optimistic”; sometimes, longing for a happy outcome, Rhys allowed herself to share her husband’s fantasies about finding a crock of gold which could be used to help poor, faraway Maryvonne and her baby daughter. Writing again provided a more reliable source of comfort; on 24 October, Jean urged her daughter to keep a diary or a notebook, adding that “writing can be (among other things) a safety valve.”16

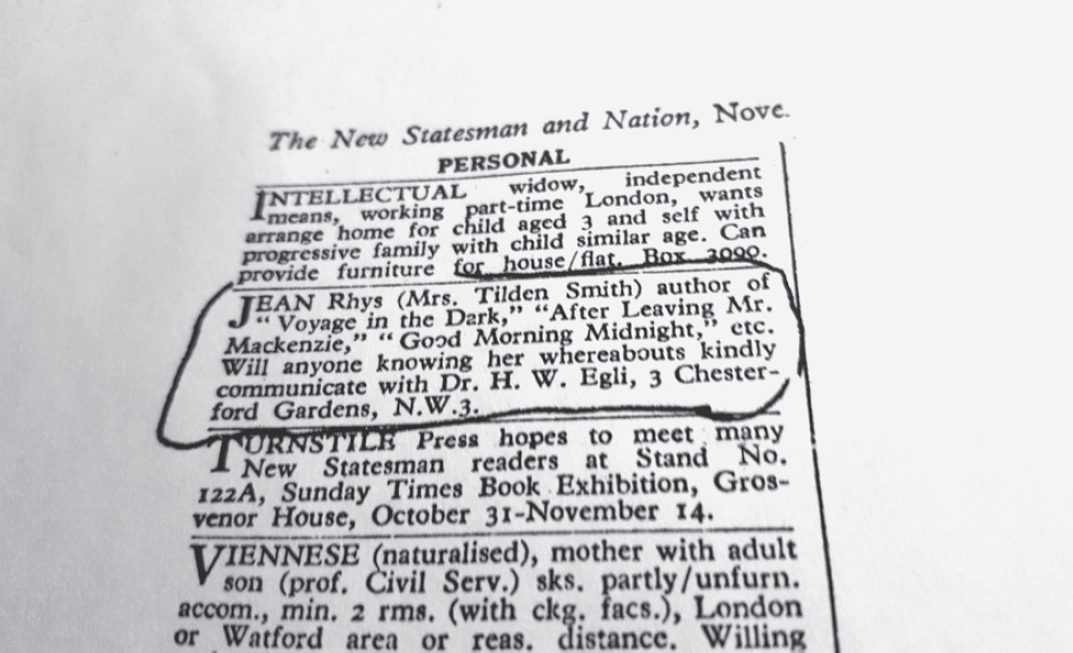

Rhys liked to claim that it was only left-wing Max who read their weekly copy of the New Statesman; (Hamer often teased his wife about her old-fashioned conservative views). If so, it may have been Max who, on 5 November 1949, found in the magazine’s back pages a small announcement requesting “Jean Rhys” to contact a certain Dr. Hans Egli in Hampstead. Dr. Egli proved to be the London economics correspondent for the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung; it was Hans’s actress wife, Selma Vaz Dias, who had placed the advertisement and who instantly responded to Rhys’s letter.

Jean must have felt dazed when she read in Selma Vaz Dias’s bold hand that the actress had come across Good Morning, Midnight in Paris, read it and fallen instantly in love with the book. As a first step towards performing it on the BBC (Miss Vaz Dias enclosed her adaptation, written for a single narrating voice), she was giving a ticketed reading to a carefully selected audience on 10 November. An admired actress and gifted promoter of new European playwrights to English audiences, Selma did not need permission to give a reading. What she had sought to discover before approaching the BBC with her project was whether Jean Rhys was still alive.

The New Statesman advertisement which changed the course of Rhys’s life. (McFarlin)

We don’t know whether it startled Rhys to learn that she was assumed to be dead. We do know that she liked the adaptation; the news that Selma also intended to talk about her earlier novels on the BBC reduced an emotional woman to tears. Writing back on 9 November, she told the gratified Vaz Dias that the actress had worked a miracle; such discerning enthusiasm had lifted “the numb hopeless feeling” that had paralysed her for so long. Now, filled with fresh hope, she could return to work.

Rhys blamed flu rather than nerves for her absence from the powerful reading that Selma gave to an appreciative audience—it included an admiring Max—at the Anglo-French Centre in St. John’s Wood. She was not too ill to proclaim her triumph in disdainful Beckenham. Haughty Mrs. Hardiman, still nourishing a grudge against her brick-throwing neighbour, promptly spread the word that Ella Hamer, a common criminal, was pretending to be a famous writer. Doubtless, she shared the joke with Rhys’s tenants; it’s clear that they seized the chance to have some sport.

On 16 November, Mrs. Daniell, having barged her way into her landlady’s bedroom at midday, offered her thoughts about the fact that the supposed great writer was still lolling in bed with a drink in her hand. Jean screamed at her. When Mrs. Daniell responded by tipping a rubbish bin—perhaps it was only a wastepaper basket—over Rhys’s head, Jean lost any last shred of prudence. Still in her nightclothes and clutching Selma’s letter as proof, she ran out into Southend Road, proclaiming her identity and shouting that her work was going to be performed on the radio.

Back at Bromley Magistrates’ Court, on a charge of causing a public disturbance and holding up traffic on what was never a bustling thoroughfare, Jean was ably defended by Max. The case was dismissed. Rhys’s tussles, however, were making excellent copy for the local press. “Mrs Hamer Agitated” ran the headline in bold black print which appeared on 24 November in the Beckenham and Penge Advertiser; as luck would have it, this was the very day on which Selma had arranged to visit her heroine in Beckenham.

Selma did not see the newspaper article, although she might have wondered why her distracted hostess poured out a cup of boiling water when her visitor had asked for coffee. Unconscious of the undertow of anxiety, Selma stayed on late into the evening, praising Rhys’s work and promising her a golden future. Everything, in Selma’s breezy view, was going to turn out splendidly. The Hamers, both of them, were enchanted by their new friend.

WHO WAS SELMA? Why were the Hamers so enthralled? Tara Fraser remembers her grandmother well enough to conjure up Selma’s throaty announcement to Rhys as she first sailed into view: “Darling, I want to be the first to tell you: your work is glorious!”17

Jean Rhys’s biographers and editors have been harsh judges of Selma Vaz Dias. The time has come to redress that critical imbalance and to understand why Rhys was enduringly grateful and loyal to this extraordinary woman.

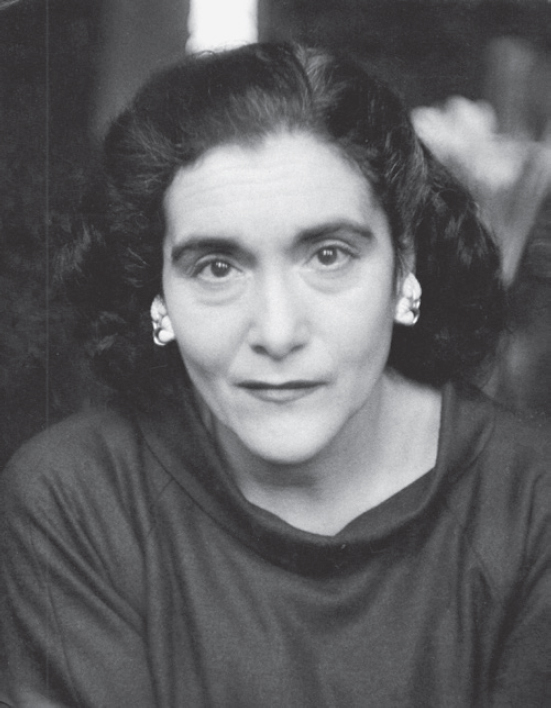

Selma Vaz Dias, the charismatic woman who entered Rhys’s life in 1949. (Used with permission of Tara Fraser)

Born in Amsterdam in 1911 (Selma’s old-fashioned Dutch was good enough for her to attempt to correspond with Maryvonne in Mrs. Moerman’s first language), Selma Vaz Dias had suffered a tragic loss during the Second World War when her adored brother Sieg was executed for his courageous work with the Dutch resistance. Exotic, passionate and widely read, Selma had won her first major role—acting alongside John Gielgud in a Russian play, Red Rust—at the age of sixteen, straight out of RADA, where she had been awarded the prestigious annual Gold Medal. Married since 1936 to a respected journalist, a dapper president of the Foreign Press Association known for his vehemently anti-Nazi views, Selma’s bright star was still in the ascendant when Rhys entered her orbit.

Today, it’s difficult to appreciate that Selma, back in 1949, appeared a far more significant figure than Jean Rhys. Since the war, she had been working closely with the BBC on plays and short stories selected and often translated by Selma herself, while introducing English audiences to the work of Genet and Lorca through the readings in the original languages that she regularly gave at the prestigious Anglo-French Centre. Shortly after meeting Rhys, Selma would join forces with Peggy Ramsay (not yet the formidable theatrical agent she would become), in order to form the First Stage Society.

Like Rhys, Vaz Dias possessed a volatile personality. Her brother’s death had triggered a breakdown, leading to electroshock treatment. On the day of her Beckenham visit, however, the actress was elated by the warm reception that had been given to her latest reading. Having described her triumph to Rhys, Selma expanded on her plans to perform Good Morning, Midnight in her own adaptation, on the Third Programme. BBC radio drama was still in its first decade and the idea of one woman occupying airtime for almost an hour was unthinkable. But Selma’s faith in her project was absolute. The play would happen. She knew it.

And so, having painted her bright vision and filled Rhys with hope, Selma swept splendidly away into the night.

THE EXCITED EXPECTATIONS aroused by Selma’s predictions were short-lived. On 14 January 1950, Max Hamer was charged with attempted fraud for abetting the stealing of seven cheques, to a value of £3,000 (£105,000 today), from the offices of Cohen & Cohen.

After months of worrying about the hold that Michael Donn appeared to have exerted over her naive husband, the awfulness of the reality caused Rhys’s fragile control to snap. On the same night that Max was charged, she squabbled with the most belligerent of her tenants, Mr. Daniell; the following day, a furious Rhys was thrown out of Beckenham police station after referring to Daniell as “a dirty, stinking Jew.”† Fined only £1 on this occasion, she was back at Bromley Court within days, following further allegations by her tenants of offensive behaviour.

On 30 March, Bromley Court decided to adopt the drastic course of banishing a conspicuously absent Mrs. Hamer from living in Beckenham. The mortgage company had moved more swiftly. By the end of March 1950, 35 Southend Road had been repossessed. All that was left in the Hamers’ former home, as the magistrates now learned, were two Chinese vases, a divan bed and the quietly vindicated (or perhaps noisily triumphant) tenants.

The owners themselves had disappeared.

*Jean Rhys’s insults were frequently anti-Semitic but almost always inconsistent and contradictory. Six months after her row with the Bezants in April 1949, she described her Jewish tenants to Maryvonne as “a little nest of Nazis” (Rhys to Maryvonne, 24 October 1949, in Francis Wyndham and Diana Melly (eds.), Jean Rhys Letters, André Deutsch, 1984, p. 265).

†Mr. Daniell was still nursing a grudge against Rhys thirty years later, when he wrote to her editor, having read of Rhys’s death, to inform Diana Athill of his former landlady’s insulting behaviour.