16

Cheriton Fitzpaine

“More discontents I never had

Since I was born, than here,

Where I have been, and still am, sad,

In this dull Devonshire . . .”

—Robert Herrick, “Discontents in Devon,” c.16401

JEAN RHYS SPENT her first seventeen years in Dominica because that was where her family lived. But what persuaded her to spend the last nineteen years of her life in a village of which she spoke to her London friends with a gloom to match that of the London-bred Civil War poet Robert Herrick? If she hated life at Cheriton Fitzpaine so much, why did she choose to remain there?

IMAGINING CHERITON FITZPAINE from afar, you should place this north Devon village midway between the towns of Tiverton and Crediton. Narrow the focus; cradle it amidst small, hilly fields, of which the nearest to the village are separated by narrow and winding lanes guarded by towering hedges. Out beyond the fields, to either side of this landlocked world of farming communities, lie the high and open heathlands of Exmoor and Dartmoor. Within, it’s hard to shake off the feeling of having entered a parallel universe, one in which time remains suspended somewhere between the wars. Driving down the steeply twisting little roads that lead the visitor past a neat row of former almshouses to the church, the open green and the long, thatched schoolhouse that lie at the centre of Cheriton Fitzpaine, you wouldn’t feel surprised to encounter a gaunt young farm-boy, limping home from the trenches of 1918.

Visiting to form my own impressions of the village in which Edward Rees Williams purchased a home for his sister in the summer of 1960, I met a rosy-cheeked man who’d liked growing up here enough to move back to Cheriton in early middle age. Roy Stettiford was among the youngest of a family who lived in the single-storey house next to the Hamers for many years. He remembers peeping through their window one day and seeing Rhys (an old lady, in his child’s eyes) sitting in front of a television and drinking, straight from the bottle, all by herself. “She were hard on her husband, we thought,” remains his only criticism. Roy’s memory of Max Hamer is of a friendly, pale, shortish man with a white forked beard “like a nanny-goat,” whose wool beret, pulled low over a balding pate, gave him a bit of a foreign air: French, they thought.2

Cheriton Fitzpaine, the secluded Devon village in which Rhys spent the last nineteen years of her life. (Used with permission of Piers Howell)

The most radical change about life in Cheriton Fitzpaine—after Bude and Perranporth—was that on Cornwall’s north coast, the Hamers had lived among people who were used to the regular influx of strangers who visited every summer. Cheriton has never—until Rhys became famous—attracted tourists. Here, Jean and Max found themselves dwelling among conservative Devon families of modest means, people who tended to view as an outsider anybody who came from farther away than Exeter or Plymouth. The Hamers’ nearest neighbours felt at home living alongside the fields that belonged to Landboat Farm, owned and run by the Carrs, a staunchly Methodist young couple who didn’t drink and who cared about land, not books. Max and Jean thought differently. They were, and would remain, apart.

Edward Rees Williams had seen no reason to brief anybody other than Cheriton’s vicar about his sister’s unpredictable moods. The sudden bursts of rage that Rhys’s drinking habit often engendered shocked her new neighbours and sometimes frightened them. Many stories are still recalled of the kindnesses that were regularly performed for the Hamers, especially as Max became increasingly infirm and his wife less able to care for him at home. Nevertheless, it remains an uncomfortable fact that a handful of village families did encourage their small sons to persecute an elderly woman whom they regarded as a stranger and a witch. “I am envied and hated,” Rhys reported to Selma Vaz Dias in the autumn of 1963, adding, two months later, more nervously: “the gossip is dreadful. . . .”3

Viewed on a bright summer morning, the centre of Cheriton Fitzpaine looks idyllically pretty. The long walls of the schoolhouse gleam white under its steep roof of thatch; standing beside the rectory, a visitor can easily spot where the tower of St. Matthew’s rises into view, solid and reassuring. Walking beside me along a hillside lane flecked with mud and cow dung, Roy Stettiford talks in a soft Devon accent about the village his parents first knew. Back then, Cheriton Fitzpaine was a thriving little community with its own post office, butcher’s and grocer’s shops. Hard times had shrunk the village; arriving in the late summer of 1960, Rhys and Max found themselves dependent for all necessities on two pubs and a small store for general supplies. For books, Rhys relied for several unsatisfactory years on the fortnightly visits to the village of a mobile library van.

I hadn’t expected Cheriton’s rectory to be so old or so appealing, but Roy Stettiford explains that the house was once home to the Arundells, a family of public-minded rector-squires who put on plays for the village and rewarded good Sunday-school pupils with an occasional outing to the Tiverton picture house. An older villager, Ken Sanford, remembers games of tennis, always in whites, taking place on the high flat lawn that lies behind the rectory; Roy remembers scrumping for apples in the orchard. In 1964, Rhys told Selma Vaz Dias of the pleasure she always derived from watching the huntsmen trotting past on a bright winter’s morning; a last trace of the days when the Arundells hosted the Eggesford Meet, an annual gathering of hounds, horses and their riders that took place in the heart of the village.

The rectory played an important role in Rhys’s life at Cheriton. By 1960, the Arundells had been replaced by Alwynne Woodard, the only person among the villagers who swiftly understood that an exceptional writer was living in their midst.

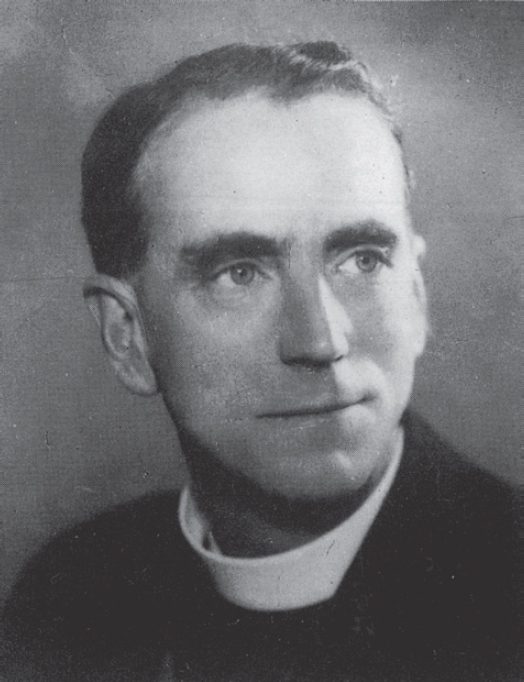

Woodard was a remarkable priest—“a dear, the real McCoy,” as Rhys gratefully wrote to Diana Athill in the late summer of 1963.4 The grandson of a Victorian canon who had founded a group of evangelical schools, Alwynne was educated at one of them, Lancing. Returning there as a young schoolmaster, he taught classics and English to Evelyn Waugh. Unjustly dismissed by a headmaster who was then himself forced to leave, Woodard spent many years doubling as a rural dean and the well-liked chaplain to a psychiatric hospital in Surrey, before settling into the less demanding role of vicar to a tiny parish of which only a small percentage were regular churchgoers.

The Reverend Alwynne Woodard, the cultured, compassionate and broad-minded vicar who came to Rhys’s help while she was struggling to write Wide Sargasso Sea.

A bookish, dreamy man, Woodard was married to a conscientious and necessarily patient woman who supervised weekly basket-weaving classes in the rectory’s front room, while one of their four daughters amused herself by painting saucy murals above the staircase. The vicar’s vagueness was notorious. (On one occasion, the absent-minded Alwynne actually allowed his spouse to fall out of their car, while driving inattentively on.) But it was the Reverend Woodard’s goodness of heart that Roy Stettiford and Ken Sanford both singled out to me for praise: “He were always kind, a very kind gentleman indeed.”5

Woodard’s first recorded encounter with the Hamers was unfortunate. A few months after the couple’s arrival, Rhys had been enraged by the erection of a barbed wire sheep-fence close to the bedroom window of their new home. A neighbour, alarmed by the wildness Rhys displayed when her blood was up, summoned the vicar to arbitrate; Rhys, on this occasion, was both drunk and furious. Nevertheless, while trying to soothe her, Woodard felt an unanticipated sense of rapport.

It was shortly after this incident in the spring of 1961 that the vicar started to make occasional afternoon visits to the intriguing Hamers. Sometimes, to the consternation of a watchful village, he took along a bottle of whisky and shared its contents with a woman whose mind had struck him from the first as being out of the ordinary. Keeping clear of the topic of difficult neighbours, they talked about books. It seemed that Cheriton’s odd new resident was trying to complete a novel. The vicar loaned her Tom Jones, which she didn’t much care for; his response remains unknown to the copy which Rhys despatched to him of Orwell’s Animal Farm.

Woodard’s appreciation of Rhys as a writer began on an autumn evening in 1961 when, informed by his sobbing friend that she had destroyed her novel, he decided to gather up the scrawled sheets of paper that lay in heaps around the room. Back at the rectory, Woodard persuaded one of his daughters to help assemble the semi-legible handwritten pages into some kind of an order. Helen Woodard eventually retired to bed; the vicar, having spent most of the night patiently collating pages, managed to decipher enough of Parts One and Two of Wide Sargasso Sea to recognise that the work in progress was exceptional. From then on, Woodard paid regular and sometimes daily visits to the Hamers’ home. He “cheered me up when I was at my last gasp,” Jean would tell Diana Athill in August 1963, marvelling at Woodard’s kindness to a non-churchgoing member of a community by whom “I’ve been given up as a bad job I fear.”6

TODAY, JEAN RHYS’S home is the last still standing of a small row of undistinguished one-storey properties: the rest have been destroyed. Across the lane, a hillside field has already disappeared under a new, larger hamlet of residential homes.

The cottage (a word suggestive of a quaint charm that Rhys’s home lacks) is now and always was screened from the curious eyes of passers-by, protected by a dense green hedge. To the back of the bungalow, beyond a muddy plot from which Rhys struggled to create a flower garden, she could glimpse cattle and sheep as they roamed the hillside fields. This was Rhys’s favourite outlook. Writing to Francis Wyndham in the summer of 1967, at the time of her proposed departure for the less remote Essex flat that had been selected for her future home by Diana Athill, she lovingly recorded all that she could see from her small sitting-room’s window: two successively flowering lilacs, a honeysuckle, two apple trees, peonies, Michaelmas daisies, “and so on.” That careful inventory spelled out what Rhys could not quite bring herself to admit to her London friends. Despite Miss Athill’s kind endeavours to improve her lot, she really did not want to leave Devon.7

Rhys was not a skilled plantswoman, but there’s no doubt that she loved her Landboat plot. Writing to her daughter in July 1961, Rhys tried to explain the restorative effect on her spirits of digging in the garden: “I like the smell of earth and grass . . .” Two days later, she told Maryvonne of the pleasure she had derived from bringing into the house a single unidentified crimson flower: “not to be believed it is so beautiful.”8 In later years, chatting with her celebrated Devon neighbour, William Trevor, Rhys only ever wanted to talk about one subject: gardening. Encountering the elderly lady out walking in her long coat and neatly knotted headscarf, the younger writer always supposed that the wicker basket on Rhys’s arm was for the purpose of gathering flowers. Villagers knew better: Jean’s basket was used to carry her bottles home from the local pub.9

I revisited Cheriton in 2021 and met Sam Moss, the proud owner since 2004 of Rhys’s former home. Like Rhys, Sam often hears scrabblings from the cottage’s attic and doesn’t relish making an investigation.10 In their early days at Landboat, one of her sons used to see an old lady sitting by his bed: photographs identified her as Jean Rhys. Today, Sam is good-humouredly used to being approached by Rhys’s fans. The most regular visitors to Cheriton are Dutch. We agree that it’s time the cottage had a plaque to honour Rhys’s nineteen years of residence.

Despite improvements having been made during the last years that Rhys lived here—and many more since Samantha Moss moved in—everything within Landboat Cottage (as it is named today) feels cramped and undersized. Back in 1960, the year of the Hamers’ arrival, a tiny bathroom stood just beyond the door: “a delightful thing to have one,” Rhys crowed to Maryvonne: “a luxe.”11 To the right, an equally small kitchen became her workroom. Here, an open oven door kept Rhys warm while she wrote at a table covered—Caribbean style—with a bright square of chequered oilcloth. Overhead, a naked orange light bulb provided a luridly inadequate substitute for the dazzling sunlight of a Caribbean childhood.

Space was always limited. Behind the bathroom, a minute spare room became a store for the battered suitcases in which Rhys kept old manuscripts and drafts. Beyond the kitchen, the Hamers’ bedroom was dominated by the old-fashioned dressing table at which, throughout her life in Devon, daily court was held by Jean with her reflected image, reddening pursed lips, blueing lowered eyelids, blotting out the evidence of many a sleepless night. From the sitting-room to the rear of the cottage, little windows stared across the garden plot to where a distant line of scrubby trees stood beyond the first hillside field. Rhys evoked this view in one of the many poems that she despatched at irregular intervals to Francis Wyndham. She called it: “A field where sheep are feeding”—and acknowledged an evident debt to Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha.

The silent field powdered with moonlight,

And the low hills

The low, meek unaspiring hills.

And the tall trees

The tall proud dark trees

Leaning down to shallow water

Looking into shallow water.12

Rhys’s enduring grievances were not with the smallness and inconvenience of a house in which water from burst pipes frequently dripped or cascaded through the low ceilings, but with a ramshackle iron-roofed shed. Large enough to house Edward’s car when he drove over either to deliver a Christmas capon, or to make peace with an irate Landboat neighbour, the empty shed also offered a perfect nesting place for mice. Rhys’s attitude to animals could be capricious: a dog lover in earlier years, she was terrified by the pale-eyed mongrel sheepdogs that sometimes roamed the lanes in Cheriton. Cows might be endured (“They know who to shy at,” Rhys joked to the resolutely urban Francis Wyndham13). Mice were another matter. Rats were worse.

During the nineteen years she spent at Landboat, Rhys’s correspondence makes it almost possible to predict the onset of a mental health crisis by the increase in her allusions to the unwelcome presence of largely imaginary rodents. In September 1963, writing to Selma Vaz Dias, Rhys claimed that an invasion of mice had caused her—not for the first time—to tear up a chapter of the ongoing novel. (“But that’s no excuse.”) Writing to Francis Wyndham in October, she darkly noted her growing terror of “my mouse-haunted kitchen” and her creation of a barrier of wood and stones to keep vermin at bay: “quite useless of course. Also there are alarming sounds from above where the hot water pipes are. (Things larger than mice?).”14 Edward Rees Williams became sufficiently worried about his sister’s state of mind to pay an inspection visit that same autumn; what he saw in her did not reassure him.

This may be the second-hand caravan Rhys bought with Jo Batterham in the last years of her life. Its grim appearance nicely conveys the imagined horror of the sinister shed which forms such a feature of her letters from Devon. (McFarlin)

WHEN CORRESPONDING WITH an increasing number of friends and admirers in London, Rhys seldom missed an opportunity to voice her dislike for Cheriton Fitzpaine. In December 1960, while writing about the “marooned” Cosways in her novel, she described herself to an anxious Maryvonne as “simply marooned.” Like the unhappy young priest at Ambricourt in Georges Bernanos’ celebrated novel—Diary of a Country Priest was a book that seldom left Rhys’s side—she felt that the village was watching her, cat-like, with suspicious eyes. Reaching a particularly low ebb in the early autumn of 1963, when Max was away in hospital, Rhys wailed to Selma Vaz Dias that the villagers hated her “because I try to write . . . More than half the population think I am a witch! And that I do harm!!”15 A follow-up letter identified the vicar’s wife—no fan of Rhys—as having relayed the village’s suspicions of witchcraft. Mrs. Woodard had added that her husband was praying for Mrs. Hamer’s redemption.

“This is not a place to be alone in,” Rhys wrote to Selma in that troubled autumn of 1963. The words were heavily underlined; the letter described her home of three years as “stupid,” “ugly,” “beastly” and even “evil.”16 In some part of her mind, Rhys believed it all. “Sleep It Off Lady,” the unnerving title story of her last collection, represented Rhys herself in the guise of “Miss Verney,” an overimaginative and often intoxicated old lady who—having been perused and told to “sleep it off lady” by Deena, the cold-eyed child of a disapproving neighbour—is left helplessly lying on open ground in the chilly air of approaching night.*

Bad things did happen in the village during Rhys’s time there. In 1966, Diana Athill brought back to London an unnerving tale of having been robbed as she lay awake in Rhys’s newly built annex by a night visitor who used his long-handled hook to reach through the window and snatch her purse.17 Athill’s tale was true: the thief, a local boy, was subsequently arrested. Miss Verney’s miserable death of overnight exposure was the product of Rhys’s imagination. So, to a certain degree, was Rhys’s much proclaimed loneliness. Evidence abounds, both in the villagers’ memories and in Rhys’s own letters, of endless acts of kindness towards an eccentric outsider who had settled for good in a village that was neither ugly nor evil. Miss Verney’s occasional and gently outspoken visitor, “Mr Slade,” is a thinly disguised portrait of Rhys’s friend Alan Greenslade, her regular taxi driver and—through his always available telephone—her principal contact with the outside world. Mrs. Greenslade and Roy Stettiford’s mother often cooked meals when Rhys wasn’t eating, and helped to care for Max. Women like Joy Haslehurst, who never featured in Jean Rhys’s plaintive letters to London, were always around to join Mrs. Hamer for a drink at the pub and to see her safely home. Kind Devon friends took Rhys on day outings to local landmarks and beauty spots. Alwynne Woodard watched over her and would summon Edward whenever further help was required. Joan Butler, the prototype for cliché-prone “Letty Baker” in Rhys’s story of Miss Verney, paid regular visits. Rhys habitually misrepresented her situation at Cheriton when sharing her thoughts with the outside world. Loneliness was always more a state of mind than a fact of her existence.

Jean Rhys did not love Cheriton Fitzpaine, but it was the place to which she always chose to return. In 1964, on the brink of making her first visit to London in seven years, Rhys admitted to Eliot Bliss that she was already plotting her escape back to Devon: “I’ve been down here too long and have almost taken root,” she confided before adding with typical bravado: “– though not quite!”18

CHOOSING HER WORDS with care for a modest 2017 leaflet that records Jean Rhys’s nineteen-year residence in Cheriton Fitzpaine, Diana Athill concluded it by saying that “here it was that by her own choice, Rhys came to the end of her days.”

The words sound a little grudging (Athill would certainly not have chosen Cheriton for her own final years), but they are accurate. For Rhys, a recluse who believed that she must “earn” her death by her writing, a quiet retreat in the tedious, secluded depths of Devon was ideal. Robert Herrick, a poet and priest who elected to return to Dean Prior after being ousted from his Devon parish during the English Civil War, would have agreed:

Yet, justly too, I must confess

I ne’er invented such

Ennobled numbers for the press

Than where I loathed so much.19

*Rhys’s description of the malevolent child is often assumed to have been an unkind representation of the daughter of one of her Landboat neighbours. She was also drawing on Georges Bernanos’ troubled Seraphita, the farm child who, in his Diary of a Country Priest, identifies the priest’s drinking habit and tells malicious stories about him.