22

“The Old Punk Upstairs”* (1977–79)

“The more I realise the precariousness of Jean’s hold on calm, the more valiant she seems to me.”

—Diana Athill to Francis Wyndham, 1 January 19801

JEAN RHYS WAS a woman who compartmentalised her friends. So did Sonia Orwell. This helps to explain why Jo Batterham and Diana Melly only met each other late in 1976, a year during which Sonia, working out a plan with Melly for Rhys’s future, organised a rota of volunteers to ensure that Rhys, however physically incapacitated, could continue to enjoy her annual visits to London. Several illustrious artists, poets and writers joined the list, although few of them offered more than lip service.

What Batterham and Melly importantly shared was an understanding of the crucial importance to their old friend of details that less sensitive acquaintances might have overlooked. Jo took endless trouble to see that the latest cottage furnishings were in just the right colour to satisfy the changeable wishes of a peculiarly demanding client; interminable discussions took place over the precise shade of yellow velvet for a chaise longue on which a lame octogenarian author might regally recline (Rhys was a great admirer of Sarah Bernhardt’s receiving mode) when being viewed by inquisitive journalists. Diana Melly, whose major test of her friendship with Rhys was yet to come, was already putting herself out to hunt down the perfect dress, the exact shade of pink lipstick and even the facial masseur whose calming hands could best restore an illusion of youth to match Rhys’s indomitable spirit. More than any other of Rhys’s friends, Melly understood how anxiously an outwardly successful old woman continued to fret about her appearance.

Work on Rhys’s memoir had progressed well enough in the early part of 1977 for David Plante to tell Sonia that Rhys was worrying about having mislaid an incomplete account of her early years in Paris (“L’affaire Ford”) which she was evidently planning to revise for inclusion in Smile Please. The published memoir ends just before Rhys’s first encounter with Ford; the absent section would have let us know—as perceptive readers might already have guessed from the early novels, in which Ford’s identity was apparent—that there had been a love affair.

The reward that Rhys had chosen for her own hard work was to be a winter fortnight in Venice, with Diana Melly and Jo Batterham as her appointed chaperones. Rhys’s only prior knowledge of Italy derived from a few blissful days spent in Florence with Jean Lenglet, when the couple had visited the Uffizi and gazed at The Birth of Venus, the painting that became Rhys’s favourite work of art, along with the Winged Victory in the Louvre. Had Lenglet pointed out the younger Rhys’s resemblance to Botticelli’s young goddess, skimming the rippling waves aboard her scallop-shell as detachedly as the pale palaces of Venice’s Grand Canal float above their supportive reflections? Maryvonne, who had visited Italy with her husband, Job, described Venice as the most enchanting of European cities. Venice, then, it must be.

Shepherded on board for her first—and first-class—aeroplane flight, a terrified but excited Rhys sipped courage from a mini-bottle of complimentary champagne. Landing, she was conducted to a hotel which had been specially chosen for its romantic associations. Confirmation of Rhys’s unquenchably romantic taste comes from Peter Eyre’s recollection of being asked, when he visited Cheriton Fitzpaine in 1974, to bring with him recordings of Wagner’s Liebestod and highlights from Der Rosenkavalier. Where, then, in Venice should Jean Rhys stay but at the hotel that had been home to Alfred de Musset, to Marcel Proust and even to Wagner himself?

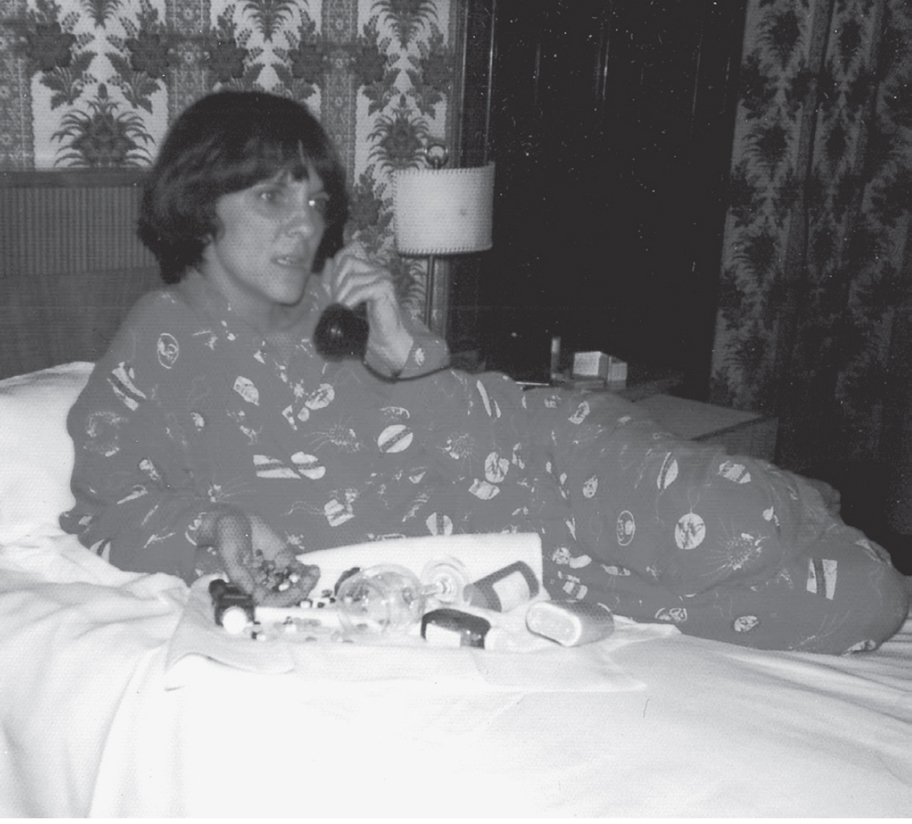

Passers-by can still glimpse the ornate corner bedroom on the first floor of the old Danieli (not the modern extension) which Rhys occupied during the last week of February and first ten days of March 1977, while Jo and Diana made do with a humbler room next door. Diana’s faded travel snaps confirm the state of general enjoyment that glows out of the long, chatty letters despatched by Jo to Sonia in Paris. Here, we see slender, dark-haired Diana and stockier, beaming Jo pushing a crumpled Rhys along in a wheelchair (she was too lame to cross the stepped bridges on foot). There, a careful Diana arranges Rhys’s battalions of pills (a task which Diana enjoyed as much as lovingly tidying the five little purses of cosmetics without which the elderly Rhys still never left home). In one image, Rhys waves from the balcony of her high chamber to a throng of tourists, obliviously passing by; in another, a cushioned bolster enables a smiling Jean to gaze at the ravishing city from the back of a gondola.

Life followed an orderly pattern. Rhys’s mornings (a leisurely breakfast in bed followed by a lengthy tryst with the hotel’s hairdresser) released Diana and Jo from their duties until the stately lunch in the hotel dining room which was Jean’s favourite treat of the day. Back at the Danieli after a brisk post-prandial hour of being pushed around the city’s chilly calle and campi, Rhys drowsily read Hemingway’s novel of Venice, Across the River and into the Trees (renamed “Across the Street and into the Grill” by a mischievous E. B. White). Next door, Jo tapped away, clattering out a daily journal of events for Sonia while Diana, when not busy knitting as she enjoyed a tranquillising joint, studied the hefty hotel bills. A substantial reduction in their meal and bar charges followed her divulgence to the Danieli’s impressed manager that their elderly guest was a writer of international renown.

Diana Melly arranges Jean’s battalion of medications, a task that pleased her orderly mind.

Jo Batterham, pushing a rather depleted Rhys across San Marco in her wheelchair. (Used with permission of Diana Melly)

Evenings began with Negroni cocktails in the hotel bar, where the handsome pianist was always ready to serenade Rhys with one of her favourite old French songs by Piaf or Charles Trenet. Later, after the light snack, glass of cold milk and early bedtime on which Rhys always insisted, Jo and Diana sauntered companionably out, in search of a more vibrant Venice.

Bad moments were rare. “We seem to laugh the whole time, it’s in the air,” Jo wrote to Sonia—and Jean agreed.2 Back in Devon and writing to congratulate Melly on the good reviews for her own first novel, The Girl in the Picture, a grateful Rhys—she had spent a cheerful week with the Mellys after her return to London—thanked her and Jo again for contributing to her happiness: “You were both so good to me.”3

Venice gave Rhys a sustained feeling of joy that she had rarely found before, except in an enchanted moment of epiphany. Asked by Tristram Powell, at the end of his television interview with her, whether—had she her life to live over again—she would choose to write, or to be happy, there’s no forgetting the pathos with which a yearning Rhys cries out: “Oh, happiness!”

FOUR MONTHS AFTER the trip to Venice, Diana Melly received a summons to Devon. The University of Kent, a leader in the rapidly expanding field of Commonwealth literature since 1964, ran a course on African and Caribbean-related studies. Rhys’s own recent contribution to Caribbean literature was to be acknowledged by the university with an honorary doctorate.† The invitation had come from Professor Louis James, who had been visiting Jean since 1975. Since Rhys was understandably reluctant to attend the long, formal ceremony at Canterbury, three representatives of the university, including Professor James and Mark Kinkead-Weekes, had decided to visit Cheriton, bringing with them a black gown, a diploma—and a tape recorder.

Rhys returns to her room at the Danieli after waving to the crowds. (Used with permission of Diana Melly)

Rhys’s first official sign of academic recognition, while eased by the arrival on the previous night of a tanned Diana Melly (with a sulky-faced boyfriend in tow), proved a less happy experience than her visitors had anticipated. A glass of champagne failed to calm Rhys’s nerves, while the discovery that the imposing gown—as with Vogue’s dresses—was simply offered on loan lowered her spirits considerably. The real ordeal was yet to come, when Rhys listened to the oration that had been pre-recorded for her imagined pleasure.

On the following morning, 21 July 1977, Rhys wrote to Louis James, author of the recorded oration, to berate him for having dared to suggest that, while her father had always been considerate towards his black patients, he had been any less attentive than to his patients who were white. All were equal in his eyes: this was the point which Rhys wished to stress. She was mollified by the news, resulting from James’s own researches, that “all of Roseau” had followed Dr. Rees Williams’s coffin through the town.4

Diana Melly spent a peaceful night in Rhys’s new cedarwood annex before her return to London; Jo Batterham, visiting Rhys a few weeks later to discuss some further improvements to the cottage’s decoration, alarmed both Sonia Orwell and Diana Athill by reporting that Janet Bridger was neglecting her duties and showed no concern for poor Jean’s appearance. Janet’s cooking was denounced as atrocious; worse, Bridger ordered Rhys about. How lucky for their old friend it was (Jo remarked) that she still possessed kind neighbours like the Stettifords and Mrs. Raymond—the Greenslades had both died—to bring in meals and to lock the door each night (a precaution taken after Athill’s frightening experience when a boy burglar stole her purse from a bedside table in the new annex).

Jo’s mention of the reported death of Brenda Powell, the last survivor of Rhys’s immediate family, was added almost as an afterthought to her long letter. Brenda had suffered nearly a decade of slow mental decline and the siblings had not spoken for many years; nevertheless, according to Janet, Rhys had burst into tears when she heard the news. Brenda had belonged to the old Caribbean world in which, endlessly rehearsing the scenes and sentences of her memoir, Rhys now—and perhaps, always—dwelled more intensely than in the present. (“Swing swing,” Rhys wrote over and again in her notes, seeming to remind herself of the perpetual shift between past and present experience that had formed a key element in the time-shifting structure of Voyage in the Dark: “Swing swing.”)

Dictating her episode-driven recollections to Michael Schwab in the summer of 1977 (David Plante had decamped for a long holiday in Italy), Rhys slipped effortlessly back into the mind of a little girl, the doctor’s favourite daughter, growing up in Roseau at the end of the nineteenth century. Titled “The Yellow Flag,” and eventually placed in the opening section of Smile Please, a fragment of an early draft which survives in the British Library’s Rhys Papers describes the abandoned Victorian quarantine station around which Rhys had once played with her friends. The published version quotes a few lines from an old military ditty which the children sang as they rocked to and fro on the “broad and comfortable” seats of their chosen playground’s swings.

Rhys’s original draft of the song had included the response given to a young maid’s naive plea for a husband. “How can I marry such a pretty little girl, / When I haven’t got a shirt to put on,” the married soldier teases the girl, as she innocently hastens to provide the elegant clothes her dashing suitor claims to lack. “Swing swing,” Rhys added at the end (as well as the start) of her draft—and she marked out that second “Swing” with a long, low and suppliant “S,” one that looks as if she intended it to represent a small, submissive body. The station was “a safe, bland, self-satisfied place,” Rhys wrote in her final version, before adding: “and yet something lurked in the sunlight.” As with the childhood memory related in After Leaving Mr Mackenzie of a frightened little girl running home from a silent, sunlit place, and never revealing what has scared her, it feels as if Rhys has deliberately placed on view a sinister recollection from the past, as sharply evoked as the unspoken scent of terror that haunts some of Henry James’s most troubling works. The connection is not irrelevant; Rhys’s letters show that she had read The Turn of the Screw at least six times.

Dark thoughts ran deep within Rhys, and never more so than when she was alone in Devon. The Canadian-born Janet Bridger took it calmly when a stone was flung at her one day in Cheriton, a village where outsiders were often viewed with suspicion. Bridger was a good deal more frightened when, following an altercation with Rhys, she found herself locked inside the cottage with its owner, who, elfishly taunting and triumphant, flourished aloft what Rhys imagined to be the only key to the door. Janet’s thankful recollection of a spare key, kept in a dresser drawer, flattens the climax of her dramatic tale with her escape into the Devon night, but it also adds plausibility to a disturbing episode.

BY THE LATE summer of 1977, it was becoming apparent to Rhys that she could no longer rely upon friends to take care of her whenever she left Devon. Francis’s spare time was occupied by the needs of his dying mother, while Sonia Orwell was frequently absent in Paris. In August, Rhys looked into the possibility of spending time at a Catholic retreat in London, vaguely referred to as “The Blue Nuns.” Informing Sonia of the failure of another tentative plan, Rhys confessed a modest dread of imposing her weakened body and its daily needs on the kindness of well-meaning acquaintances. “Between you and Di [Melly] you are really Jean’s only hope,” Sonia wrote a little desperately from Paris to Jo Batterham on 16 August; three weeks later, Rhys herself echoed that sentiment. “I haven’t got many friends in London now,” Jean told Jo, “in fact, Diana Melly and yourself are the only ones I’m sure of.”5

Sonia was acting with the best of intentions when she arranged for Rhys and Janet Bridger to spend the autumn of 1977 together at Oatlands Hotel, an expensive nursing home in Surrey. Grand surroundings—the hotel stood proudly on the site of a royal Tudor palace—failed to disguise the ubiquity of wheelchairs and medical trolleys. Janet fled back to Devon after three dispiriting days; visited by a sympathetic Athill, Rhys glumly joked that one ancient resident’s enthusiasm for killing off new germs must be directed at herself, the unwelcome new pest. Of course (as Rhys acknowledged with a giggle), she was being paranoid, but please, couldn’t Athill find her a way to escape? Diana did her best, placing a carefully worded advertisement for rooms in a private London home that might suit a “distinguished elderly woman” with independent means and “outside sources of care.” An unknown Mrs. Hatch offered an upstairs bedroom with narrow stairs up which her daughters could carry an elderly tenant, when required. If they were around. If they chose: it’s hardly surprising that Rhys turned the offer down.6

The obvious solution was for Rhys to be taken in either by Jo Batterham or by the Mellys. But taking Jean in also meant gratifying her expectations, which were often unreasonably high. “I know [clothes] shopping is tiring,” the eighty-seven-year old Rhys hopefully advised Jo on 27 October, “but I find it so exciting and it would please me so much.” The fact that a distraught Jo felt unable to face the ordeal of conducting a frail old woman around London’s finest dress shops had much to do with the fact that her beloved Gini Stevens had just left her to marry an American.7

Rhys was unaware that the kind-hearted Mellys were already on her case. George was sympathetic to needy women, especially when they were as interesting as Jean Rhys; Diana relished the idea of rearranging their family home in Gospel Oak—only the first-floor rooms housing George’s magnificent collection of surrealist paintings were ruled out of bounds—in order to ensure the happiness of a cherished guest.

The preparations, outlined in an entertaining and moving article which George Melly would publish some thirteen years later, were tremendous. George relinquished his beloved box mattress, the lowest and least dangerous form of bed the Mellys could produce for an unsteady old lady with brittle bones; Diana, moving out of her own airy bedroom on the second storey of a three-floor maisonette at 102 Savernake Road with views of Hampstead Heath, redecorated the entire ensuite in what she knew were Rhys’s favourite shades of pink: rosy pink lampshades; sunrise pink curtains; marshmallow pink for the freshly painted wooden floors. The result, so an admiring George recalled with the sad hindsight of 1990, was “incredibly pretty . . . as warm, cosy and mildly exotic as a gypsy caravan.” Here, surely, even such a perennially wistful writer as Jean Rhys might allow herself to feel happy? “She would have no practical worries, proper meals, lots of treats and outings, friends when she wanted company, help with her make-up, an important chore . . .” (George had already persuaded the Mellys’ friend Mary Quant to send Rhys a bag of her daisy-themed cosmetics during the summer) “. . . and any amount of love and goodwill. We were longing for her arrival.”8

Of the three months that the octogenarian Rhys would spend under George and Diana’s roof, the first two were an almost unqualified success. A document of proof survives in the form of a daily journal kept by the Mellys’ lodger. Fresh from reading Oriental Studies at Cambridge, young Sarah Papineau found their guest captivating, demanding, and capricious.9

It took a week, so an intrigued Papineau recorded in her diary, for a haphazardly coiffured Miss Rhys (increasingly blind and averse to wearing glasses, Jean often put her pink or white wigs on back to front) to venture down the stairs. A few days later, Sarah attended a kitchen lunch at which a radiant Rhys—Diana had spent the morning shopping on her behalf at Chic, an expensive Hampstead boutique—regaled the two of them with memories of her early years in Paris. Publicly, Rhys had always been resolutely discreet; feeling herself to be among friends on this occasion, she opened up. It seemed that she hadn’t warmed to the Fitzgeralds, but the dashingly handsome Hemingway, praised for his matchless skill with dialogue in fiction, was approvingly described as having been “shy and unassuming” in person.‡ She mentioned an early experiment with opium as a disappointment (it had produced no effect at all), before expressing a shy curiosity about the musky joints that Diana Melly was pleasurably inhaling with her coffee. (A shared spliff would often prove useful when Rhys became emotional.) Still tucking into her toffee pudding, Rhys begged for her appointment with an unknown new doctor to be deferred; she didn’t want to be seen looking “awful” by a stranger. “She looked beautiful!” an admiring Sarah added to her journal of a memorable day.10

At home with the Mellys at Savernake Road. (Used with permission of Diana Melly)

Sarah Papineau swiftly became Diana Melly’s dependable supporter in the house, taking Rhys breakfast in bed, helping her to clamber into the bath and sometimes rushing back early from her evening waitressing duties at Ronnie Scott’s, just to make sure that their celebrated visitor was safe and snug in her room. On 27 November, in a typical diary entry, Sarah noted that she had carried up the stairs a three-course lunch prepared by herself for their guest. A happy afternoon chatting to Rhys about punk rock had prefaced a warm invitation to Devon. Later that day, after the novelist Bernice Rubens had popped in for a quick visit (Rubens had her own house key to the Mellys’ easy-going home), Sarah took Jean’s glass of milk upstairs and settled the honoured guest safely into her bed.

The combination of circumstances was extraordinary. Here was a reclusive and frail old lady residing as the acknowledged queen of a household where jazz music, modern art, recreational drug-taking, theatre chat and the Mellys’ own complicated love life, created a heady brew. Athill, after dropping in from her nearby home in Primrose Hill, reported to an anxious Sonia that, while “pink and lame,” Rhys looked “ravishing” and “happy as a bee.”11

Events that had been painstakingly arranged for Rhys’s enjoyment didn’t always go well. George recalled the uncomfortable lunchtime occasion when Jean mischievously informed a disconsolate Penelope Mortimer, the respected author of The Pumpkin Eater, that Caroline Blackwood was the only woman writer in England who wasn’t actually murdering the language. (Rhys had been devouring Great Granny Webster, Blackwood’s disturbing and award-winning story of a loveless old grandmother, obtained by Sarah Papineau at Jean’s urgent request.) The actor Peter Eyre, arriving for lunch at Savernake Road on a chilly day wrapped in a long, high-collared coat, had to be asked to leave because his appearance reminded a weeping Jean of the doomed aristocrats in the Russian Revolution. Contretemps often proved entertaining: George Melly’s mother visibly sulked when Rhys hogged the limelight at a Christmas family lunch, while Al Alvarez was told off after giving a giggling Jean so much champagne that she fell on the floor: “all her recent accidents have been due to that,” Sonia Orwell reproachfully reminded Diana Melly from Paris.12

Some of the disasters had comic overtones: Rhys once pulled so hard on the lavatory chain that the whole cistern crashed down; on another occasion, Diana Melly crossly compared herself, the forceful Athill and Jo Batterham to limp tea towels as they debated whether to answer angry thumps on the floor above, reminding them that a trapped Rhys wanted a top-up to her drink. Requests were not always so graceful. A polite manner had long concealed the formidable power of Rhys’s will. As age stripped away the niceties of courtesy, she grew ever more ruthless about exerting that remarkable faculty to get her way.

By and large, Rhys threw tantrums only in the company of those she knew could be subdued. George, who allowed nobody to subdue him, could spend a tranquil evening watching an old Hitchcock film with their guest, or chatting about books. (A well-read Francophile, George shared Jean’s affection for Breton’s Nadja.) His wife, meanwhile, resigned herself to a volley of screams and curses whenever—which was increasingly often—she failed to please. “The thing is that you never know whether to talk to an old woman or to Jean,” Diana Melly sighed to a distant Sonia, while wishing she could do more to make their guest happy. Sometimes, caressingly patted and told that she possessed the Caribbean islanders’ gift for creating “magics” (a form of bewitchment) as she perched on the edge of Jean’s bed to share a puff of her own late-evening joint, Diana believed for a fleeting moment that she had succeeded.13

There were many good times. Rhys loved being taken to Ronnie Scott’s to hear George singing with John Chilton’s band, the Feetwarmers, for whom she wrote the ruefully ironic lyrics to “Life Without You.” But her patient hostess was not alone in feeling the strain. Take a Girl Like Me, the admirably candid memoir which Diana Melly published in 2005, recalls the occasions on which a grey-faced David Plante crept down their stairs from a tough two hours of labouring over the smallest details of Rhys’s memoir. “I had now heard Jean’s stories many times,” he would write in Difficult Women. Rhys’s title—Smile Please—was a given; the content now consisted of endless tiny refinements, the same ones being made over and again to the text that he was perpetually being instructed to read aloud. “Shit!” Rhys would shout if David spoke too quickly, or if some unbidden memory caused her pain. And then, out of the blue, just as when she assured Diana Melly that she possessed the power of “magics,” there would come a murmured observation that caused all the humiliation and despair to slide away. Today, Plante still remembers how much it meant whenever Jean Rhys spoke to him as a valued colleague, explaining, on one fondly recalled occasion, the difficulty she always had with creating a sense of space around each word. “Yes,” he remembers her saying in her soft little voice. “I tried to get that. I thought very hard of each word in itself.”14

On 7 February 1978, Rhys was chauffeured to Buckingham Palace to receive a CBE from the queen. Diana Athill had persuaded one of the academic world’s most adept fixers, Noel Annan, to arrange the honour; it was an award which appeared a perfect way to crown Rhys’s achievements. A small celebration lunch was held afterwards in the Mellys’ home at which Jean presided, smiling, sober and impeccably dressed. Her conversation with the queen was reported to have been pleasant but brief; it seems unlikely that Her Majesty was one of Rhys’s keenest readers.

By February 1978, the dark side of Rhys’s volatile personality had begun to emerge once more. Al Alvarez arrived at Savernake Road just in time to dissuade a distraught Jean from tearing up a latest—and last—short story: thanks to Alvarez’s intervention, a delicate homage to Dominica and to Rhys’s best-liked cousin, Lily Lockhart, “The Whistling Bird,” would be published in the New Yorker in September that year. Diana Melly reached a point at which, so she recalls, she often felt like physically spitting into the bowl of soup being carried upstairs to their screaming guest. George Melly jokingly suggested that the two unhappy ladies might perhaps like to go in search of the local canal and drown themselves after supper. Plante, shocked by the violence of one of Rhys’s rages, took an unkept vow never to visit her again.

What was going on? In part, the problem derived from the fact that Rhys felt both beholden and insecure. Kind though the Mellys had been, they were not her family and, however thoughtful their behaviour, she could imagine herself as their prisoner, shut away in her pretty pink suite. Rhys was also unsettled by the news that had reached her of a biography that Thomas Staley was determined to write. Confiding in his English friend John Byrne on 28 December 1977, Staley admitted that Rhys was reported to be unhappy and even alarmed, but added that he intended to go ahead with a critical work in which only a single chapter would be addressed to her personal life.15 A chapter was still enough to cause dismay, however; having been distraught by Arthur Mizener’s revelations in his biography of Ford, Rhys feared the very worst for herself at the hands of another American academic.

Equally terrifying to an old lady living in a house that was not her own was the prospect of being abandoned. Planning a winter weekend at her Welsh retreat during George’s absence on a road trip, Diana Melly persuaded Sarah Papineau to return to act as Rhys’s companion at Savernake Road. It was already well known that Jean liked Sarah. All, surely, would go well.

Returning from Wales three days later, Diana was greeted by an exhausted and ashen-faced Sarah. She described Jean as having passed completely beyond reason; entering Rhys’s bedroom, Diana was met with such fury that its force seemed to hurl her back against the door. Melly remembers it having been on the following day that Maryvonne Moerman was informed by a wild, knife-wielding Rhys that she would slash George’s treasured surrealist paintings to ribbons if her daughter dared to leave the house. According to Diana, the usually stoical Maryvonne passed out from sheer fright.16

The change in Rhys at this point was absolute and devastating. Her loving hosts had become the enemy. Everything they did was wrong. Nicknaming her “Johnny Rotten”—after the punk prince of bad behaviour—was George’s way of trying to dispel a darkness in which no glimmer of light appeared. All their good times had been blotted out. Rhys ranted to everybody who dared to come near her that she was a helpless victim, deserted for weeks on end by a woman who—the unkindest cut of all—produced hideous clothes which her imprisoned guest was then compelled to buy. Even now, Diana was trying to prevent her from going home. Of course, as George wrote in his ruefully honest account of the debacle, the converse was true: “Di could hardly wait.”17

Sonia, advising the Mellys from Paris, knew Jean Rhys well enough to take her new mood seriously. Writing to Diana, she warned her that “you must, must must protect yourself.” Conscious that Diana herself had a fragile psyche and that she was heroically determined to escort Rhys down to Devon, Sonia warned her not to go unaccompanied: “You must not be alone with her at Cheriton Fitz.”18

Diana did as she was told. A workman joined her for the long journey when, towards the end of February 1978, she escorted a glowering Rhys back home. Reports of heavy snow ahead almost forced their car to turn back; Jean’s face conveyed her scepticism. Only the presence of large drifts beside the narrow lanes leading down into Cheriton finally convinced her that “bad weather” was not part of a cunning plan to drag her back to Savernake Road. Flowers sent by Jo Batterham and a warm welcome from her Landboat neighbours were received in silence. Not a word was forthcoming, not even when Diana and her companion thankfully took their leave.

It was difficult for Diana Melly to acknowledge such abject failure, when she herself had tried so hard. The persona she would self-mockingly name “Mrs Perfect” (and even crown with a cartoon halo in her 2005 memoir) had imagined that she possessed the ability to make Jean Rhys feel happy. Writing to Sonia in Paris, Diana sadly admitted that “I can’t do that, I can’t even make her feel all right.”19

NORMALLY, A CHANGE of scene could lift Rhys’s spirits, but not this time. Visiting Cheriton in May to record Rhys’s latest minute revisions to her memoir, David Plante grew so disheartened that he took Joan Butler’s advice and left after two days. When Jo Batterham tentatively reminded Rhys that she herself was still owed the cost both for an elegant chaise longue and its expensive upholstery, Rhys rebuked her for preying upon a helpless pauper. And yet, as Batterham sadly recalls, nobody could have been kinder after Gini Stevens’s defection than Rhys, who took her out to lunch and—offering a pretty flower across the table—gently reassured her unhappy friend that life would brighten with the coming of spring.20

Dictating an essay, commissioned by Harper’s, to a flattered Janet Bridger (Janet wrote it neatly out by hand on sheets of pink paper, all ready for the typist), Rhys could still rally her powerful gift for sardonic self-scrutiny, even in the last year of her life. “Making Bricks without Straw” offered a darkly comic self-portrait of the author in interview mode, wondering how much eyeshadow to apply and where to place the chaise longue in order to expose her face to the most flattering light. But, once again, the peevish voice of complaint pushed its way to the fore. Why must these well-meaning interviewers always assume that Rhys’s own life had been as miserable as the wretched women whom she described? Why must they keep trying to pigeonhole her as a white Creole, or as a feminist?§ And why must they regard every careless word she uttered—after the couple of stiff drinks required for the ordeal of being interrogated—as gospel truth?21

The essay was written for public consumption. Privately, Rhys recognised that she was fast losing the war between a frail body and her ferocious will. “Well, you are a fighter,” remarked one of the nurses who now regularly came in to bathe her, when Rhys refused to make use of her cane to stump back into the bedroom. Maybe so, Rhys pondered in one of her last, painfully executed handwritten notes, but, “What exactly am I fighting for?”22

By the end of the summer, professional interviews had become too taxing for Rhys to undertake. Nevertheless, when Olwyn Hughes and Diana Athill mentioned a young book rep who was visiting Exeter and eager to meet her, Rhys managed a handwritten note to welcome Madeline Slade for a visit to the cottage in what would be the last autumn of her life. Feigning surprise when her guest arrived, Rhys was nevertheless beautifully dressed and—as it was mid-afternoon—eager to be poured a gin and vermouth. Dismayed by the cottage’s exterior, Slade complimented her hostess on the transformation that had been worked within. (“She told me how hard she had tried to make it look nice.”) Once Slade had put away a typed list of questions, Rhys relaxed, asking whether Madeline was a writer, too. (“She got very serious when I said I’d stopped. ‘It doesn’t do to stop,’ she said. ‘You need to keep practicing.’”) But what remained with Slade most strongly was Rhys’s response when a woman neighbour called in. (“They chatted about the woman’s young daughter, and Jean was so interested; she wanted to know how the little girl was; everything about her. Just then, when she forgot I was there, I thought that she seemed really happy.”)23

ONE OF THE free-standing sections of Rhys’s memoir (dictated almost without hesitation to Michael Schwab during the post-Venice summer of 1977) had described “Meta,” the abusive nurse whose harsh behaviour and suggestive name (so close to the Latin mater) seem to connect her to Rhys’s mother. Smile Please makes no pretence of a happy relationship between the author and Minna Lockhart. But it was to Minna that Rhys touchingly dedicated the completed pages which reached Diana Athill in November 1978. “This is such a cold, grey country,” Julia Martin had imagined her mother sadly saying of England, shortly before her death at Acton in After Leaving Mr Mackenzie. “This bouquet I hand to you, my silent mother, who died so unhappily in a cold country,” was what Rhys wished her final and most personal work to say, perhaps as a token of apology for her own past lack of sympathy for Minna’s loss of her husband, her home, her health and—even—of her difficult daughter. It’s always startling to realise the number of years during which a literary perfectionist like Rhys could continue to meditate upon the best way to use a particular phrase, once it had taken root in her mind.

The memoir was already overdue for publication; given Rhys’s age and increasing frailty, the risk of waiting for a revised second portion covering the author’s life after her arrival in England was deemed too great. Athill decided that the book should be edited immediately and published within six months. Privately, Diana admitted to Anthony Shiel her disappointment at the meagre “Brownie snaps” Rhys had supplied as illustrations; writing to Jean, Athill combined enthusiasm with some practical observations. Two submitted episodes from Rhys’s later years didn’t sit comfortably, in Athill’s view, with the remarkable evocation of her childhood in Dominica. The story of the completed Imperial Road—Rhys’s last attempt to smuggle that deeply felt false memory into print—would also have to go. And so—but Athill did not tell Jean this, or offer any explanation—would the words she had specifically chosen as a dedication to her mother. Later, when Diana offered David Plante the chance to become Rhys’s posthumous dedicatee, he refused. David, in his own odd but passionate way, did love Jean Rhys. He knew what Jean herself had wanted.

Unaware of the fate of her carefully worded dedication, an always meticulous Rhys worried that Athill appeared to be less concerned with checking the text than with reshaping the book. (Loosely linked episodes were skilfully rearranged by Athill and assigned titles: “Geneva”; “The Doll”; “Carnival”; “Paris,” and so forth.) On 12 December, an apprehensive Rhys wrote to ask Oliver Stonor what she could do about it all. Nothing, was the dispiriting answer. Esther Whitby, who had returned to work part-time at Deutsch, confirms that it was customary practice, when Athill was busy, for any proofreading tasks to be passed along to a colleague. In this case, although Athill was indeed distracted, since her mother was dying, Smile Please never left her own possessive hands.

The result of what seems to have been Athill’s combination of necessary haste and an uncharacteristic inattentiveness amounted to a flurry of careless errors and misprints in the published text of Rhys’s last work. Courteously pointed out to Athill by Oliver Stonor in 1979—his handwritten list survives in the McFarlin archive—they have never been corrected. In her preface to Smile Please, Diana poked fun at Rhys for (so Athill claimed) having objected to the absence of a mere “then” and a “quite” from the published text of Wide Sargasso Sea. Such a prodigiously careful reviser of her own work would assuredly have been dismayed to see “Brokenhurst (for Brockenhurst), “No Theatre” (for Noh Theatre) and a celebrated Italian play quaintly retitled Paula and Francesca, appearing alongside a playwright called Richard Brindsley Sheridan and a piece of sheet music titled “Flora Dora” (a misnaming of the charming Edwardian musical, Florodora, which Rhys had artfully slipped into her childhood memories as a foreshadowing of her life on stage). It’s a shame. Smile Please seems to have been the work that Rhys herself valued more than any other she wrote, perhaps because it was so personal and achieved in such difficult circumstances.

AT THE END of 1978, and still concealing from friends and editors alike her actual age of eighty-eight, Rhys felt vigorous enough to plan a spring trip to London. In February 1979, a “crack-up,” Rhys’s habitually terse code for a breakdown, took her instead into a nursing home near Exeter. Her appetite had become bird-like. Always conscious of her weight—she had hated it when, during the 1960s, she briefly became a little plump—Rhys boasted to Oliver Stonor of having shrunk to a mere six stone. Addressing a new admirer, Elaine Campbell, she gallantly promised to write the foreword to a planned reissue of Phyllis Shand Allfrey’s Caribbean novel, The Orchid House.

“Onward and upward,” Rhys chirruped to Stonor from hospital. Sure enough, by 11 March, she was home again and feeling strong enough to ask Diana Melly to book her into Blake’s (London’s most luxurious boutique hotel was a firm favourite with Princess Margaret) for a month of final revisions. Evidently, she intended to regain control of her precious text.

The details have never been entirely clear about the fall which took Rhys into a West Country city hospital rather than to Blake’s Hotel in the late spring of 1979. Diana Athill, no fan of Janet Bridger’s, wondered whether an obstreperous Rhys might have been given a rough shove before Janet remorsefully settled the dazed old lady into a chair and hastened home. Janet herself claimed that an intoxicated Rhys had been alone when she fell. Urgently recalled to the cottage by one of Rhys’s alarmed neighbours, Bridger had summoned the doctor, who diagnosed a fractured hip bone. Immediate attention was required. Rhys was rushed by ambulance to the main hospital in Exeter.24

Rhys’s ancient body failed the trial of anaesthesia and surgical invasion. For six weeks, disabled and silent, she lay in the Creedy Ward of the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital. Plans for the spring publication of Smile Please were resumed after Athill had paid a brief, unsatisfactory visit to Rhys’s bedside. A few days later, George Melly, popping into the hospital on his way to keep a jazz date in Exeter, had trouble in recognising the shrunken features of a patient identified on the information card above her bed as: “Joan.”

On 14 May, a sudden impulse caused Jo Batterham, who had taken her son out for lunch from Bryanston School that day, to drive west on a seventy-five-mile detour to Exeter. Having found her way to Creedy Ward, Jo shared George Melly’s difficulty in recognising the pale, wigless little figure whom she found clawing at the bedclothes, open-eyed and staring, but unable to speak. The doctor in charge, when questioned, breezily opined that “Joan” might survive another month. Appalled, Batterham left the hospital and drove down to the coast. Walking beside the sea, so Jo says today, she “just willed” her ancient friend to die. Back in the ward, she clasped one of Rhys’s restless hands and softly sang the Piaf song that seemed to fit the moment best: “Non, je ne regrette rien.” (“And do you think she did regret anything?” I ask. “I doubt it,” answered Jo.)25

Back in London that same evening, Jo heard the news that Rhys had died and rang Diana Melly. Diana told her that she was looking out of the window, watching a pink cloud sail away, high above the rooftops of north London. “And there goes Jean,” Diana said.26

The Stonors, who were holidaying in France in the spring of 1979, learned from their young friends, Olive and Christopher Cox, that Rhys’s funeral in Exeter had been a muted affair. Maryvonne and her daughter, Ellen, represented the family; friends included Francis Wyndham and the two Dianas (Athill and Melly). Peggy Ramsay sent lavish flowers; Al Alvarez, although absent, wrote an obituary in which he reaffirmed his view of Rhys as one of the most important British writers of the twentieth century, while praising Francis Wyndham (appointed by Rhys as her literary executor) for his unstinting perseverance and enthusiasm. Selma Vaz Dias, two years dead, went unmentioned in the tributes.

Some years after Rhys’s cremation, Diana Athill arranged for the placing of the modest memorial—for which Maryvonne chose the wording—which stands in the graveyard of St. Michael’s at Cheriton Fitzpaine. At present, no stone or plaque commemorates Jean Rhys on the green Caribbean island where she was born and where—speaking to us through Antoinette Cosway in Wide Sargasso Sea—she hoped to die. “If you are buried under a flamboyant tree,” I said, “your soul is lifted up when it flowers. Everyone wants that.”27

When the clearance of Rhys’s cottage began, this pink mohair shawl, a gift from Sonia Orwell, was still hanging, neatly folded, on the back of her writing chair. (Used with permission of Carmela Marner)

Following the overnight demolition of her family’s Roseau home in 2020, nothing physical survives to connect Rhys to Dominica, the island where she had—more directly than through Antoinette—told Phyllis Shand Allfrey that she wished her bones might be buried. “I Used to Live Here Once,” the title of a story completed four years before her death, suggests that Jean Rhys already knew the truth. There would be no return. There was no need. The island that had cast its haunting spell over Rhys’s imagination would live on, enduringly, within her work.

*Borrowed from the title of a 1990 newspaper tribute by jazz musician and memoirist George Melly to his friend Jean Rhys (“The Old Punk Upstairs,” Independent on Sunday, 28 October 1990).

†The influence on Rhys’s postwar writing of the distinguished Caribbean authors living in London during the 1950s remains underexplored. It wasn’t by chance that Rhys chose to recast her own experiences as those of Selina Davis (“Let Them Call It Jazz”), a light-skinned newcomer to London from the Caribbean.

‡Rhys’s account adds a little credence to Jean Lenglet’s claim in a Dutch publication that she had introduced him to Hemingway, whom he allegedly interviewed for his former employer, the New York Herald Tribune.

§Rhys steadfastly declined to be a poster girl for feminism. At Holloway, she had expressed her solidarity with the suffragettes who were imprisoned there. But when asked for her thoughts about the brave suffragette who had died after throwing herself in front of a galloping horse on Derby Day in 1913, Rhys, who adored horses, expressed her sympathy for the colt.