Allied Secret Intelligence Compromised, 1944

On 14 December 1944, Alastair Sandford wrote to his friend Lieutenant Colonel R.A. Little, the long-serving Deputy DMI. It was a friendly and personal letter in which Sandford outlined his visit to Melbourne and his intention to take a few days’ leave in Adelaide before going to Darwin. Sandford was heading to Darwin to arrange the accommodation for the Canadian Army’s Special Wireless Group (SWG), which would soon be arriving to conduct intercept operations. After this long preamble, Sandford got to the point and, as is often the case when the preamble is long, the news was bad.

What Sandford had to tell Little was that the worst thing that could possibly befall a SIGINT agency had happened at Central Bureau. Central Bureau was now intercepting its own intelligence being passed by the IJA in Harbin, China, to the Japanese Imperial HQ in Tokyo.1 Japan had breached ‘Y’ security and were reading their own messages being reported in Allied communications. It was exactly what Lieutenant Rudy Fabian, OP-20-G, the US Navy and the US Army, as well as the ‘Y’ authorities in Britain, had feared. Poor Australian security had shattered the security of ‘Y’ Procedure.

What was worse, it was not just Sandford and his senior officers who were aware of this breach, so too were the British and Americans. The failure of Australia’s security could not be hidden, and, amazingly, Group Captain F.W. Winterbotham, the Chief Security Officer for ULTRA in the UK government and Squadron Leader S.F. Burley, who was responsible for the distribution of ULTRA to British formations in the east, were in Australia and visiting Little in Melbourne when the news broke.2 They were in Australia to deal with ‘a number of extremely difficult breaches of security’, including the fact that the source of the Japanese intelligence was, ‘as we suspected…the Soviet Ambassador in Australia’.3 The question was, as Sandford put it, ‘how the Japanese obtain the information from the Soviet[s] and secondly, how the Soviet Ambassador himself obtains the information’.4

The information in this letter was for Little’s ‘ears alone’ and the only other person who appears to have been aware of this crisis was the CGS, General Northcott, and perhaps, the C-in-C, General Blamey.5 This was not the first time that ‘Y’ Procedure had been compromised in Australia, and it most certainly was not the first time that Australian secrets flowed out of Australia.

Problems first appeared in 1940, when Australia was provided with intelligence derived from the communications of the Japanese Consul-General in Sydney. This detailed the Consul-General’s intelligence reporting as including the name of a British man-of-war berthed in Sydney Harbour to the Imperial HQ in Tokyo. The Consul-General was also reported as having passed technical intelligence on New South Wales’s power transmission line between Sydney and Newcastle, and information on the floating dock in Newcastle.6 He was even able to report on the reorganisation of the Australian Army’s 8th Military District in Port Moresby, accurately listing the islands brought under that HQ.7

A month later, another British intelligence report message, classified SECRET, was passed around Melbourne and Canberra. This was obviously derived from SIGINT, as it provided the details of another message from the Japanese Consul-General in Sydney to his government in Tokyo. This dealt with Australia’s purchase of training aircraft from Japan in exchange for wool and wheat, and included the Consul-General’s recommendation that Tokyo provide an accommodating response, in the hope of splitting Australia from the United States.8

It is clear from these reports that GC&CS was reading Japanese diplomatic traffic and sharing the intelligence with Australia. It also shows how poor was Australia’s handling of sensitive information.9 Not only were these reports passed around the service chiefs, they were sent to officials, including committee secretaries and junior staff officers.10 Among them were the Assistant Secretary of the Defence Committee, Frank Sinclair; the Assistant Secretary of the Department of Defence, Lieutenant Colonel A.J. Wilson, who was also the War Book Officer; and the liaison officers for the three services.11 There was effectively no compartmentalisation and no control.

Paul Hasluck provides a good example of this state of affairs in his autobiography, Diplomatic Witness, where he describes his first day working as a public servant in the Department of External Affairs in Canberra. He found the department housed in ten rooms coming off a single corridor. Each room was full of desks covered in unsecured papers, and in one room the cipher section worked loudly enough for them to be easily overheard in the corridor. The Central Records Room, the most important room in the department, was located just inside the main entrance and, ‘from the point of view of security’, was ‘in the most vulnerable place that could have been chosen’.12 There were no guards and no restriction on access.13

The only security advantage Colonel W.R. Hodgson’s department held was that it worked in utter chaos. The chaos was so bad the officers of the department could not find files, making it likely that no spy could either. According to Hasluck, who later wrote the civil volumes of the Official History of Australia in the War of 1939–1945, the department’s files were ‘among the worst organised and the worst kept’ of all Australia’s archives. External Affairs worked on ‘personal memory’.14

The issue of Australian insecurity was not confined to officials; it came from the very top. In April 1941, British government officials in London were startled to read in The Times information that could only have come from Most Secret cables that had just been tabled in Cabinet. The Times had not got a scoop; rather, it had reprinted a report from the Sydney Morning Herald of 23 April. Australia’s prime minister, Robert Menzies, had sent the contents of the cables to his deputy, Arthur Fadden, without the permission of Churchill or any other British authority. On 26 April, an embarrassed Menzies was urgently cabling Fadden that he was ‘amazed at the close relation’ between the report in the Sydney Morning Herald and the texts of the cables.15 The subject matter within the cables included the German order of battle in the Balkans, and this could only have come from ULTRA.

Given this incident, it is easy to see why Britain was concerned at allowing Australia to undertake ULTRA work when this subject was raised a little time later. The fact that the British were so pragmatic and so tolerant is something Australian history has been slow to acknowledge. Menzies’ behaviour in this case was appalling.

With those in the very top of government prepared to ignore security when it suited them and officials who could not run their departments properly, it is no surprise that Australia’s security services were abysmal. They lacked cohesion, resources, training, procedures, protocols and any understanding of what ensuring security meant. They spent their time looking for German and Italian spies who did not exist and in harassing Italian priests, Jehovah’s Witnesses and anyone else they deemed a security threat. They completely missed the growing networks of NKGB and GRU (USSR foreign military intelligence) spies and agents that would later compromise ULTRA and the standing of Australia as a country that could be trusted.

The other subject they completely overlooked was education on and enforcement of proper security arrangements in government departments. The armed services had their own arrangements, imported from Britain, and these extended to ‘Y’ Procedure and its own completely independent security arrangements. Outside of these, however, it was up to every government department and agency to make their own arrangements, and so there was no security anywhere outside of the armed services.

In 1942, in response to growing American and British unease at Australia’s insecurity and the establishment of FRUMEL and the Central Bureau, Australia finally formed a new Security Service. It turned out to be just as dysfunctional as its predecessor organisations. London continued to worry about the ‘little problems’ with the ‘new Security Service in Australia’.16 But hope trumped realism at the Security Service in London when E.E. Longfield Lloyd acted as an intermediary on behalf of the new Australian Director-General of the Security Service, Brigadier William Ballantyne Simpson.17 This led to the Security Service allowing Lloyd more time to bring some method to the new service. He didn’t, and it kept chasing priests and Italian cane growers, and eating in Chinese restaurants to find Japanese spies listening to the conversations of officers. They remained completely unaware that Soviet intelligence had penetrated their own service and many Commonwealth government agencies, particularly External Affairs. These were the agents stealing Australia’s secrets for the Soviet Union. These secrets were duly passed from Moscow to the Soviet Legation at Harbin, from where Australia’s DMI, Colonel Rogers, and other Australian officers believed they were in turn obtained by the Japanese.18

By early 1943, concern about Australian security had increased in London and Washington because of the growing complaints from FRUMEL and the US Navy. Major General Stewart Menzies, the head of SIS, signalled Major General Dewing, the senior British officer in Australia, to relay that he was now ‘greatly concerned about the way in which the Australian military was handling ULTRA Japanese diplomatic material’.19 C questioned ‘whether Australian authorities fully appreciate importance of security concerning this material’. C’s main anxieties were the distribution controls in place and just who was seeing the diplomatic cables.20

As we have seen, British concerns lay in the importance of Japanese ULTRA to the intelligence window Britain had into high-level German planning.21 Seen from this perspective, C’s approach was reasonable. He wanted Dewing to assure him that Australian security was sufficient for ULTRA and that Australia would put the necessary controls in place in the same way as the other Dominions. If he got this assurance from Dewing, then C would cooperate fully in assisting Australia to develop its capabilities in Japanese diplomatic cryptanalysis.22

Luckily for Australia, Dewing was a reasonable man. In his reply to C, he outlined the difficulties between FRUMEL and Central Bureau, and emphasised Fabian’s unwillingness to cooperate with anybody. Dewing contrasted this with Sandford’s excellent relationships, including with Paymaster Lieutenant Commander Alan Merry, RN, Britain’s last representative at FRUMEL, and with other organisations and individuals. Dewing, in a very British way, gently pressed the knife deeply into Fabian and FRUMEL, telling C,

The information at my disposal indicates that Fabian’s [sic] has been consistently overworked and probably as a result of this his general attitude has introduced an unfortunate element into his relationship with British and Australian members of the Special Intelligence Bureau.23

Importantly, Dewing informed C that, ‘I am satisfied that present security of Sandford party is good.’24 Effectively, this message saved Australia’s efforts to develop its own ULTRA program. On 30 March 1943, Dewing confirmed that Australian security for the proposed ULTRA operations against Japan’s diplomatic traffic was sound.25 The Australian military authorities had agreed to the security regulations regarding ULTRA and SIGINT activities, and to adopting the standardised British nomenclature for identifying the various types of intelligence derived from ‘Y’ work.26 They had also agreed to ensure that all people admitted to the compartment would be indoctrinated to understand the risk that any breach of security posed in drying up intelligence all over the world. Lieutenant Colonel Little had also agreed that no Australian politician would be given access to any SIGINT.27

The security arrangements for ULTRA were not left to Australia or Major General Dewing. As we have already seen, the SIS had its own station in Australia led by Captain Kendall, and this included Lieutenant Commander Merry, who was at FRUMEL, ostensibly as an analyst on the Four Sign Japanese code. It is clear from the documentary evidence that Merry was reporting to SIS what the US Navy and the RAN were working on, and, more importantly, what they were doing with SIGINT.28 Merry also reported to Kendall in Brisbane, but he appears to have had his own communications circuit back to SIS, most likely via Major General Dewing’s office in Melbourne. It was Merry who alerted GC&CS that the Australian Secretary of the Department of External Affairs, Hodgson, had been made aware of ULTRA information.29

All now seemed to be well, but this was not to prove the case for long. On 29 July 1943, Alastair Sandford signalled C that Central Bureau had reports from ‘a fairly reliable source’, a phrase denoting SIGINT, that indicated Tokyo was obtaining intelligence from inside Australia.30 Rogers, the Australian DMI, Sandford and Little suspected the Soviet Legation in Canberra was sending the intelligence to Moscow and somehow the Japanese were getting hold of it.31 The Australians now wanted to launch a cryptanalytical attack on the Soviet codes.32

London’s response was measured, very measured, as it took more than five weeks for a reply to be sent in September, prompted even then by a number of later signals from Sandford.33 The reply came from C, as the Chair of the ‘Y’ Board, and it downplayed the incident, telling Sandford the Soviets used one-time tables for all diplomatic traffic and this made Soviet messages unreadable to both GC&CS and the Japanese. He then muddied the waters by asking if Sandford had considered that the Japanese were reading the messages being sent by other allies or neutrals in Australia. C then asked Sandford to send specimens of these messages for further investigation.34

The low-level replies to Sandford’s signal and the widening of the potential culprits to cover Allied and neutral nations represented in Australia suggests that London was running an agenda. What that was is impossible to answer, but London was well aware that secret information had been leaking to the Japanese from the Chinese Nationalists, led by the Kuomintang, in China. London was also aware that no one could trust the Soviets.

The problem of Nationalist Chinese insecure communications was longstanding.35 Nationalist codes and ciphers were low grade and easy to break, and GC&CS had been reading them for a long time, as had the IJA, which had broken them as early as 1936.36 According to Yamamoto Hayashi of the Harbin Agency of IJA Intelligence, this provided the IJA with a direct line into US and British intentions throughout the Pacific War.37

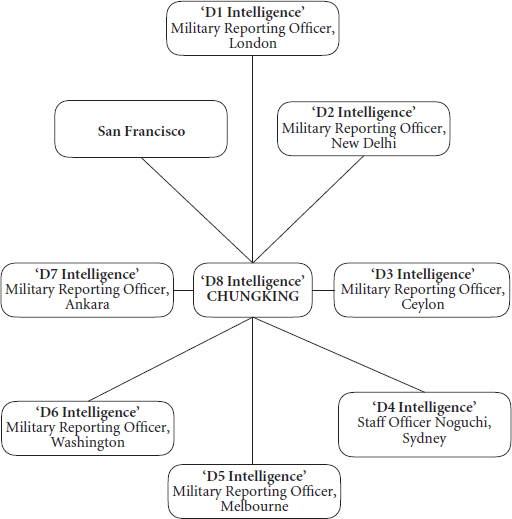

IJA SIGINT intercept operations were directed against Chinese Nationalist traffic between Chungking (Chongqing), London, New Delhi and Ceylon.38 The IJA was also intercepting communications to and from Washington and even Ankara. The communications of the Nationalist Legations in Melbourne and Sydney were also being intercepted and broken by the IJA.39 The British regarded the situation with the Nationalist Chinese as so bad that in April 1944, as the preparations for D-Day were culminating, Britain jammed China’s diplomatic radio links and stopped all diplomatic bag privileges.40 This was a serious step to take against an ally, but the needs of the moment overturned the need to be nice.

Following this spate of signals in July 1943, nothing else is seen on this case until December 1944, when investigations by Central Bureau finally uncovered the IJA’s sources as being the Nationalist Chinese military liaison officer network (see Figure 20.1).41 These liaison officers worked back to D8, the Nationalist Chinese Intelligence in Chungking. By this time, though, there was more to worry about than poorly protected Nationalist Chinese communications.

The Nationalist Chinese were not Japan’s only source of intelligence on Australia’s military activity and intelligence organisation. The Kempeitai were finding a very fruitful source that would quickly compromise the AIB and most of its operations, particularly those conducted by the SRD. This source would even compromise ULTRA intelligence by sending ULTRA material across insecure radio channels. The source was the SRD itself.

Figure 20.1: The Nationalist Chinese military’s reporting officer network, 1940s

On 29 January 1944, the SRD despatched Operation COBRA to Dari Baai on Timor and into the hands of the waiting Kempeitai. The COBRA operatives were taken and their radio operator coerced into sending false intelligence back to Australia. COBRA’s first five messages back to Australia lacked the necessary safe word (authenticator) telling SRD COBRA had not been compromised. This word was ‘Slender’, and it was only sent in message No. 6, DTG 1005Z/6/3.42 It was only sent after SRD had alerted the watching Kempeitai to the missing authenticator by inserting the phrases ‘this particular girl’ and ‘she is not the fat rpt fat one’.43 COBRA’s radio operator had broken tradecraft rules by writing the word slender in his notebook, and the Kempeitai realised the COBRA operator was alerting SRD to his compromise by omitting the authenticator.

The SRD replied to message No. 6 on 7 March, committing perhaps the most egregious breach of ‘Y’ security in Asia during World War II when it told COBRA:

Your six big relief. Col Maj C and all here sick at heart past week due intercept of Jap cipher [Author’s italics] naming you personally and apparently claiming your capture Jan 29.44

The SRD had just broken every rule in the ‘Y’ security rulebook, putting SIGINT into a low-level code and transmitting it on a normal communications circuit to a unit behind enemy lines. And they had not cleared this action with anyone.

This breach was massive. It told the Japanese that Australia and the Allies were reading Japanese codes and just how quickly they were doing so. There can be little doubt that the breach was quickly identified, as General Blamey was shown messages No. 6 and No. 8 from COBRA, no doubt trying to ascertain for himself whether the SRD had breached ‘Y’ security instructions in sending ULTRA to an agent behind enemy lines.45

The precise SIGINT the SRD had compromised was a Central Bureau report of a message sent from Davao in the Philippines to Singapore on 18 February 1944, reporting the capture of Lieutenant Cashman, whom the Japanese describe as having been ‘a student at MELBOURNE Spy Intelligence HQ’.46 That the Kempeitai in Dili placed a premium on Cashman’s information is shown by the fact that a report of his disclosures was sent to the Vice Minister of War in Tokyo and, by default, to Imperial HQ as well.47

It is little wonder that Sandford and Central Bureau were concerned, and it would explain why Group Captain Winterbotham happened to be in Australia later in 1944 dealing with ‘a number of extremely difficult breaches of security’.48

What saved the Allied SIGINT effort following this extraordinary breach of ‘Y’ Procedure by the AIB and SRD? The Japanese. Their response was to explain it away and do nothing. The Japanese told Lieutenant Cashman that ‘their cipher could not possibly be cracked, and even if it could, Australia would not send such information to the field’.49 Luckily, for the Allied SIGINT effort, the Japanese did not realise just how inept the AIB and SRD were.

By this stage of the war, mid-1944, the evidence of breaches of SIGINT security was growing, and there can be little doubt that both London and Washington now wanted action taken to protect SIGINT from any further compromise. There is also a suspicion that Captain Kendall and Third Officer Eve Walker of SIS were working with Alastair Sandford on the issue. The fact that the head of the British Special Liaison Service, Group Captain Winterbotham, was in Australia in the months immediately after D-Day suggests he had significant reason to be there.

The suspicion that Sandford was running a counterintelligence operation at Central Bureau directed against the leakage of ULTRA in Australia is only supported by circumstantial evidence. First, there is his close relationship with the SIS Station Chief, Captain Kendall, RN, and his support of Eve Walker’s counterintelligence operations against Robert Wake’s Security Service in Brisbane. As well as these, the files show that by late November 1944, Sandford had accumulated considerable evidence of IJA reporting of Top Secret intelligence derived from the Harbin Special Intelligence source. This included intelligence from the Soviet Minister in Australia on MacArthur’s plans on Leyte Island, Bicol Peninsula and Ragoru Bay, and on the decision of the Australian government not to despatch troops to the Philippines until arrangements for shipping and aircraft were finalised.50 Other information sent was so specific the analysts at Central Bureau could confirm it was derived from secret Australian reporting. It included the following:

Para. 1: The enemy’s appreciation of JAPANESE strength in the PHILIPPINES at the beginning of November (D4 report sent on November the 7th).

Sub-Para. (1) Air strength (as of November the 3rd):

| Northern Sector: | 281 planes |

| Central Sector: | 107 planes |

| Southern Sector: | 61 planes |

| TOTAL | 449 planes |

Sub-Para. (2): Ground Strength (as of November the 1st):

| LUZON ISLAND: | 161,200 men |

| Central Sector: | 51,900 men |

| Southern Sector: | 60,900 men |

| TOTAL | 274,000 men51 |

This intelligence was assessed in Australia as being identical to intelligence that appeared in the Australian Military Forces Weekly Intelligence Review No. 118, issued on 4 November and received at LHQ on 7 November, the date the Japanese believed it was issued.52 This report was stolen in Australia and provided to the Soviet Legation so quickly that the Japanese were broadcasting it on 11 November. It took the NKGB or GRU less than four days to get this report to their colleagues in Harbin, from where it was either stolen by the Kempeitai or given to the Japanese by the Soviets.53

According to Sandford, the signal containing this intelligence, MBJ 30028 of 25 November 1944, ‘caused a very considerable stir overseas’.54 The ‘stir’ was created by the fact that the information reported in MBJ 30028 was derived directly from an ULTRA and the Japanese had clearly identified the Soviet Ambassador as the original source. The other reason for the ‘stir’ was that the Japanese were rebroadcasting it only four days after it being released in Australia.

The impact of MBJ 30028 was that Winterbotham postponed his departure for Washington and the United Kingdom to meet with the DMI the following Thursday and he thought, Sandford tells Little, that ‘the matter is one of serious insecurity on a global scale’.55 At the meeting, Winterbotham was asked by the Australian DMI to bring out to Australia a ‘Special Section 5 man’, and although there is no other mention of a Special Section 5, SIS Section Five dealt with counterespionage and this no doubt referred to a plan to send the SIS officer Lieutenant Colonel C.H. (Dick) Ellis, to deal with the problem.56 In the meantime, it was ‘most imperative…that no action whatsoever be taken until his arrival’.57

On the same day as Sandford was writing to Little, Christmas Day 1944, Central Bureau issued another message from Tokyo sent on 19 December to Saigon, Rabaul and Singapore. This message provided the divisional dispositions of Australia’s military forces on Bougainville and New Britain, and in New Guinea. It was not ULTRA material, but it referenced that source D4 was Staff Officer Noguchi based in Sydney.58 Other than this disclosure, the identity of the D group of informants remained unknown until late January, when a message Tokyo had broadcast on 29 August was finally deciphered. It disclosed that the D source were the communications links between Nationalist Chinese attachés and Chungking.59 This was backed up by GC&CS work on IJN messages. Once the Nationalist Chinese communications were identified as the links, London advised Australia to cut the Nationalist Chinese government off from all access to sensitive information.60 The Nationalist Chinese as the D source was finally confirmed on 3 February 1945.61

But this did not explain Japanese access to ULTRA material. By early 1945, the Australian military authorities were sure enough to inform the Security Service that the Soviet Legation in Canberra was leaking intelligence to the Japanese, although they did not know how.62

It stood to reason that the Soviets were responsible for more of the leaks than the Chinese. Australia had already taken steps against the Chinese in April 1943, when all Australian military formations and commands were ordered to ‘ensure that no information is given to Chinese Naval or Military Attachés that would be detrimental to the Allied cause’.63 Despite this, it may be the Nationalist Chinese were still being given access to sensitive information, but why so much? The truth of the matter is that the Chinese were accidently compromising some sensitive information, but the Soviets and their Australian spies were stealing everything they could lay their hands on. The Nationalist Chinese attachés now had to have prior LHQ approval to visit any operational area.64

But the Soviet problem continued, while the Japanese and the Soviets in Harbin played games of double- and triplecross with one another. The Soviets knew that the IJA’s Ha-Toku-Cho (Harbin Special Information) organisation had penetrated their consulate, and the IJA knew the Soviets knew.65 The NKGB were using this knowledge to feed false information to the Japanese and, to make it believable, it is highly likely they would have sprinkled some gold in the mud to keep the Japanese confident of the material.66 This is a standard practice, and the use of intelligence from Australia that did not harm Soviet interests and had the double value of harming US interests in Asia, even slowing the US advance up the Pacific, fitted the bill very nicely. The Japanese, aware that there was a good chance the Soviets were doing this, carefully dissected everything they were given.67

Yet this does not explain how Tokyo was broadcasting Australian SIGINT issued on 7 November to its commands on 11 November. This intelligence was not delayed long enough to have gone through a process of careful dissection. It had either been quickly stolen from the Soviets in Harbin, a risky undertaking, or been passed directly to the Japanese by the Soviets in an effort to slow the American advance towards Japan. This was realpolitik of the highest level, and it puts to rest the idea that those communists who passed intelligence to their Soviet masters did no real harm to the war effort.

The difficulty was how to handle this issue. The advice from GC&CS via Winterbotham was clear. Do nothing, the idea being that any change would immediately draw enemy attention and this risked further, if not complete, compromise of ULTRA to the Japanese and their German allies. In his letter of 3 February to the Director-General of Security, Brigadier William Simpson, Little advised that no action be taken, but Simpson was in no mood to cooperate with the army.

On 2 February, Simpson telephoned the CGS informing him that he had received information from London that he wished to pass on to the army and that he would like an officer to be nominated to meet with him. The officer selected was Little. On contacting Simpson by telephone, Little was told that there was no information from London but Simpson wanted to talk about D (Chinese Nationalist) intelligence activity. The ploy used by Simpson, telling an outright lie, was standard practice in the wartime Security Service and among its senior officers. Little put Simpson off by pointing out that such a discussion would be pointless until Lieutenant Colonel Ellis of SIS had arrived in Australia.68 Little now contacted Sandford and asked him to send an urgent signal to GC&CS requesting Ellis’s presence in Australia. It was also agreed that Simpson would have a meeting with Blamey in Canberra on 8 February to clarify matters. Until then, the army asked Simpson to do nothing about D intelligence until he received clearance to do so.69

By 2 February, Sandford recommended that Simpson and the Security Service should not be told GC&CS was sending out the raw text of the Chungking traffic, and that he only be told the Japanese were obtaining the information from their own SIGINT operations.70 Unfortunately, Brigadier Rogers had already given Simpson the raw text from Chunking proving that GC&CS was reading Chinese communications.71

Now that Simpson had been told of the GC&CS operation, he had to be indoctrinated by Squadron Leader Burley, now the SLO in the SWPA. Burley visited Canberra to do so.72 The meeting was not a happy one, although it was not as rough as Burley expected it to be.

Simpson displayed an utter lack of ethics by staying silent during the indoctrination until Burley told him that D intelligence was derived from Nationalist Chinese attachés and not from Soviet spies.73 At this point Simpson began to argue that he had the right to disseminate ULTRA within his service, before Burley bluntly told him this could not happen. Burley then ordered Simpson, a novel experience for Simpson, to burn ULTRA immediately after reading it.74 Now, Burley reports, Simpson was ‘up on his hind legs’.75 He complained that if he could not show ULTRA to his people, it was useless. This prompted no response from Burley so Simpson started name-dropping, threatening to speak to the Australian prime minister and Herbert Evatt about ‘all of this nonsense’. He even questioned Burley’s standing because he was a relatively junior officer.76

Simpson did not know how SLOs worked. He had no appreciation of the fact that SLOs were the direct representatives of Prime Minister Churchill, President Roosevelt and the relevant national SIGINT agencies on all ULTRA matters. They were always mid-level officers, so as not to attract attention, but they held the power to cut off any commander they believed could not be trusted with ULTRA. The distribution list on Burley’s signal gives the game away. Winterbotham was the only action addressee, while the Australian authorities, including the C-in-C, General Blamey, the CGS, DMI, Deputy DMI and Lieutenant Colonel Sandford, were information addressees only. They were included as a courtesy and had no executive role in the activity.

Burley exercised his powers as SLO and made it emphatically clear to Simpson that he was forbidden to speak to Australia’s prime minister on this matter without the clearance of the CGS.77 It was now that Simpson lost all standing. Not only did he ‘bluster and brag’, he reverted to his legal training and struck out the references to the British Official Secrets Act and the US legislation covering the indoctrination process before he signed the form.78 The outcome was predictable. Squadron Leader Burley notified Group Captain Winterbotham that Simpson was not a person ‘who should handle or have access to the material’, as ‘he is obviously one who would not hesitate to act first and ask after’.79 Simpson and his Security Service were immediately and formally cut off from ULTRA. This meant that Australia was to be completely excluded from access to VENONA, the SIGINT exploitation of NKGB communications from around the world including Canberra, until many years after the formation of ASIO in 1949.

Simpson continued playing games until 19 February, when Blamey instructed him to take no action on the leaks from the Chinese attachés or the Soviet legation until further advice was available. Blamey then cruelly told Simpson, a man he did not like, that he might assist the war effort by running an education campaign on security-mindedness in government departments.80 Blamey may have been spiteful, but he had made a very valid point.

Blamey’s put-down was nothing compared to the blast that came from Winterbotham in London. He informed Australia that the authorities in London and Washington were ‘Gravely Concerned’ at Simpson’s behaviour and Australia’s continuing failure to manage ULTRA security. It was not up to the Director-General of Security in Australia to take action on the matters being discussed. This decision would only be made with the full approval of the national SIGINT boards of the United States, Britain and Australia, or there would be serious ramifications. Winterbotham’s last sentence, ‘the matter of ULTRA security is global’, made it very clear what he was saying.81

On 17 March, the CGS passed Winterbotham’s directions on to Simpson. It was the end of the matter as far as Australia’s Security Service was concerned. But it was also the end of the matter as far as Australia being an equal partner in ULTRA was concerned.

Seven months later, Simpson resigned as the Director-General of Security and ascended to the bench of the Supreme Court of the ACT, overseeing the law in what amounted to a local government area. It was not as he hoped the High Court of Australia, but it had to do, and it did allow him to potter around as the Judge Advocate General for the Australian Army and the RAAF, and to chair inquiries into wheat production and air accidents. As Director-General of Security, Simpson was one of those connections of Evatt’s who had been promoted well beyond his capacity. He was no loss to intelligence when he returned to the law.

The end of this tale falls outside the purview of this book, as it lies in the story of VENONA, the Petrov Affair and the exposure of Australia’s networks of traitors, who used their good intentions to paper over the reality of their spying for Moscow. VENONA and Petrov arose from the breaches of ULTRA security that occurred in Australia between 1943 and 1945, and it is not beyond the bounds of possibility that VENONA started in Australia. While that is not part of our story, ULTRA and ‘Y’ Procedure SIGINT are, and we now need to look at the winding-down of what was, by any measure, an exceptional wartime achievement.