Using Your American Smartphone in Europe

Landline Telephones and Internet Cafés

Long-Range Day Trips from Paris

This chapter covers the practical skills of European travel: how to get tourist information, pay for purchases, sightsee efficiently, and use technology wisely. It also includes information on taking classes in Paris or long-range day trips from the city. To study ahead and round out your knowledge, check out “Resources” for a summary of recommended books and films.

The website of the French national tourist office, www.franceguide.com, is a wealth of information, with particularly good resources for special-interest travel, and plenty of free-to-download brochures. Paris’ official TI website, www.parisinfo.com, offers practical information on hotels, special events, museums, children’s activities, fashion, nightlife, and more. (For other useful websites, see here.)

TIs are good places to get a city map and information on public transit (including bus and train schedules), walking tours, special events, and nightlife. Unfortunately, Paris’ TIs are few and far between. They aren’t helpful enough to warrant a special trip, but if you’re near one anyway, stop by (the most handy may be those at the airports); for details, see here.

Emergency and Medical Help: In France, dial 17 for English-speaking police help. To summon an ambulance, call 15. If you get sick, do as the French do and go to a pharmacist for advice. Or ask at your hotel for help—they’ll know the nearest medical and emergency services.

Theft or Loss: To replace a passport, you’ll need to go in person to an embassy or consulate (see here). If your credit and debit cards disappear, cancel and replace them (see “Damage Control for Lost Cards” on here). File a police report, either on the spot or within a day or two; you’ll need it to submit an insurance claim for lost or stolen rail passes or travel gear, and it can help with replacing your passport or credit and debit cards. For more information, see www.ricksteves.com/help. Precautionary measures can minimize the effects of loss—back up your digital photos and other files frequently.

Time Zones: France, like most of continental Europe, is generally six/nine hours ahead of the East/West Coasts of the US. The exceptions are the beginning and end of Daylight Saving Time: Europe “springs forward” the last Sunday in March (two weeks after most of North America), and “falls back” the last Sunday in October (one week before North America). For a handy online time converter, see www.timeanddate.com/worldclock.

Business Hours: In Paris, most shops are open Monday through Saturday (10:00-12:00 & 14:00-19:00) and closed Sunday, though many small markets, boulangeries (bakeries), and street markets are open Sunday mornings until noon.

Saturdays are virtually weekdays, with earlier closing hours at some shops. Banks are generally open on Saturday and closed on Sunday and Monday (though a few are open on Mondays). Sundays have the same pros and cons as they do for travelers in the US: Special events and weekly markets pop up (usually until about noon), sightseeing attractions are generally open, while many shops are closed, public transportation options are fewer, and there’s no rush hour.

Watt’s Up? Europe’s electrical system is 220 volts, instead of North America’s 110 volts. Most newer electronics (such as laptops, battery chargers, and hair dryers) convert automatically, so you won’t need a converter, but you will need an adapter plug with two round prongs, sold inexpensively at travel stores in the US. Avoid bringing older appliances that don’t automatically convert voltage; instead, buy a cheap replacement in Europe. You can buy low-cost hair dryers and other small appliances at Darty and Monoprix stores, which you’ll find in most Parisian neighborhoods (ask your hotelier for the closest branch).

Discounts: Discounts aren’t always listed in this book. However, many sights offer discounts for young people (be prepared to show your passport), students (with proper identification cards, www.isic.org), families, and groups of 10 or more. Always ask. Seniors (age 60 and over) may get the odd discount at sights, though most require you to be a citizen of the European Union (EU). To inquire about a senior discount, ask, “Réduction troisième âge?” (ray-dewk-see-ohn trwah-zee-ehm ahzh).

Online Translation Tip: You can use Google’s Chrome browser (available free at www.google.com/chrome) to instantly translate websites. With one click, the page appears in (very rough) English translation. You can also paste the URL of the site into the translation window at www.google.com/translate.

This section offers advice on how to pay for purchases on your trip (including getting cash from ATMs and paying with plastic), dealing with lost or stolen cards, VAT (sales tax) refunds, and tipping.

Bring both a credit card and a debit card. You’ll use the debit card at cash machines (ATMs) to withdraw local cash for most purchases, and the credit card to pay for larger items. Some travelers carry a third card, in case one gets demagnetized or eaten by a temperamental machine.

For an emergency stash, consider bringing €200 in hard cash in €20 bills. Keep in mind that French banks won’t exchange dollars; should you need to exchange US bills, go to a currency-exchange booth (and be prepared for lousy rates and/or outrageous fees).

Cash is just as desirable in Europe as it is at home. Small businesses (B&Bs, mom-and-pop cafés, shops, etc.) prefer that you pay your bills with cash. Some vendors will charge you extra for using a credit card, and some won’t take credit cards at all. Cash is the best—and sometimes only—way to pay for cheap food, bus fare, taxis, and local guides.

Throughout Europe, ATMs are the standard way for travelers to get cash.

To withdraw money from an ATM (known as a distributeur; dee-stree-bew-tur), you’ll need a debit card (ideally with a Visa or MasterCard logo for maximum usability), plus a PIN code. Know your PIN code in numbers; there are only numbers—no letters—on European keypads. For increased security, shield the keypad when entering your PIN code, and don’t use an ATM if anything on the front of the machine looks loose or damaged (a sign that someone may have attached a “skimming” device to capture account information). Try to withdraw large sums of money to reduce the number of per-transaction bank fees you’ll pay.

Stay away from “independent” ATMs such as Travelex, Euronet, Moneybox, Cardpoint, and Cashzone, which charge huge commissions, have terrible exchange rates, and may try to trick users with “dynamic currency conversion” (described at the end of “Credit and Debit Cards,” next). Instead, when possible, use ATMs located outside banks—a thief is less likely to target a cash machine near surveillance cameras, and if your card is munched by a machine, you can go inside for help.

Although you can use a credit card for an ATM transaction, it only makes sense in an emergency, because it’s considered a cash advance (borrowed at a high interest rate) rather than a withdrawal.

While traveling, if you want to monitor your accounts online to detect any unauthorized transactions, be sure to use a secure connection (see here).

Pickpockets target tourists, particularly those arriving in Paris—dazed and tired—carrying luggage in the Métro and RER trains and stations. To safeguard your cash, wear a money belt—a pouch with a strap that you buckle around your waist like a belt and tuck under your clothes. Keep your cash, credit cards, and passport secure in your money belt, and carry only a day’s spending money in your front pocket.

For purchases, Visa and MasterCard are more commonly accepted than American Express. Just like at home, credit or debit cards work easily at most hotels, restaurants, and shops. I typically use my debit card to withdraw cash to pay for most purchases. I use my credit card only in a few specific situations: to book hotel reservations by phone, to cover major expenses (such as car rentals, plane tickets, pricey restaurants, and hotel stays), and to pay for things near the end of my trip (to avoid another visit to the ATM). While you could use a debit card to make most large purchases, using a credit card offers a greater degree of fraud protection (because debit cards draw funds directly from your account).

Ask Your Credit- or Debit-Card Company: Before your trip, contact the company that issued your debit or credit cards.

• Confirm that your card will work overseas, and alert them that you’ll be using it in Europe; otherwise, they may deny transactions if they perceive unusual spending patterns.

• Ask for the specifics on transaction fees. When you use your credit or debit card—either for purchases or ATM withdrawals—you’ll typically be charged additional “international transaction” fees of up to 3 percent (1 percent is normal) plus $5 per transaction. Some banks have agreements with European partners that reduce or eliminate the transaction fee. For example, Bank of America debit-card holders can use French Parisbas-BNP ATMs without being charged the transaction fee (but they still pay the 1 percent international fee). If your card’s fees seem high, consider getting a different card just for your trip: Capital One (www.capitalone.com) and most credit unions have low-to-no international fees.

• If you plan to withdraw cash from ATMs, confirm your daily withdrawal limit, and if necessary, ask your bank to adjust it. Some travelers prefer a high limit that allows them to take out more cash at each ATM stop (saving on bank fees), while others prefer to set a lower limit in case their card is stolen. Note that foreign banks also set maximum withdrawal amounts for their ATMs. Also, remember that you’re withdrawing euros, not dollars—so if your daily limit is $300, withdraw just €200. Many frustrated travelers walk away from ATMs thinking their cards have been rejected, when actually they were asking for more cash in euros than their daily limit allowed.

• Get your bank’s emergency phone number in the US (but not its 800 number, which isn’t accessible from overseas) to call collect if you have a problem.

• Ask for your credit card’s PIN in case you need to make an emergency cash withdrawal or you encounter Europe’s “chip-and-PIN” system; the bank won’t tell you your PIN over the phone, so allow time for it to be mailed to you.

Chip and PIN: Europeans are increasingly using chip-and-PIN cards, which are embedded with an electronic security chip (in addition to the magnetic stripe on American-style cards). To make a purchase with a chip-and-PIN card, the cardholder inserts the card into a slot in the payment machine, then enters a PIN (like using a debit card in the US) while the card stays in the slot. The chip inside the card authorizes the transaction; the cardholder doesn’t sign a receipt. Your American-style card will probably not work at payment machines using this system, such as those at train and subway stations, toll roads, parking garages, luggage lockers, bike-rental kiosks, and self-serve gas pumps.

If you have problems using your American card in a chip-and-PIN machine, here are some suggestions: For either a debit card or a credit card, try entering that card’s PIN when prompted. (Note that your credit-card PIN may not be the same as your debit-card PIN; you’ll need to ask your bank for your credit-card PIN.) If your cards still don’t work, look for a machine that takes cash, seek out a clerk who might be able to process the transaction manually, or ask a local if you can pay them cash to run the transaction on their card.

And don’t panic. Many travelers who use only magnetic-stripe cards don’t run into problems. If you’re only visiting Paris (and not the rest of France), you will likely never encounter a chip-and-PIN situation at all. Still, it pays to carry plenty of euros; remember, you can always use an ATM to withdraw cash with your magnetic-stripe debit card.

If you’re still concerned, you can apply for a chip card in the US (though I think it’s overkill). One option is the no-annual-fee GlobeTrek Visa, offered by Andrews Federal Credit Union in Maryland (open to all US residents; see www.andrewsfcu.org). In the future, chip cards should become standard issue in the US: Visa and MasterCard have asked US banks and merchants to use chip-based cards by late 2015.

Dynamic Currency Conversion: If merchants offer to convert your purchase price into dollars (called dynamic currency conversion, or DCC), refuse this “service.” You’ll pay even more in fees for the expensive convenience of seeing your charge in dollars. “Independent” ATMs (such as Travelex and Moneybox) may try to confuse customers by presenting DCC in misleading terms. If an ATM offers to “lock in” or “guarantee” your conversion rate, choose “proceed without conversion.” Other prompts might state, “You can be charged in dollars: Press YES for dollars, NO for euros.” Always choose the local currency in these situations.

If you lose your credit, debit, or ATM card, you can stop people from using your card by reporting the loss immediately to the respective global customer-assistance centers. Call these 24-hour US numbers collect: Visa (tel. 303/967-1096), MasterCard (tel. 636/722-7111), and American Express (tel. 336/393-1111). In France, to make a collect call to the US, dial 0-800-99-0011, then the number. Press zero or stay on the line for an English-speaking operator. European toll-free numbers (listed by country) can be found at the websites for Visa and MasterCard. For another option (with the same results), you can call these toll-free numbers in France: Visa (tel. 08 00 90 11 79) and MasterCard (tel. 08 00 90 13 87). American Express has a Paris office, but the call isn’t free (tel. 01 47 77 70 00, greeting is in French only, dial 1 to speak with someone in English).

Providing the following information will allow for a quicker cancellation of your missing card: full card number, whether you are the primary or secondary cardholder, the cardholder’s name exactly as printed on the card, billing address, home phone number, circumstances of the loss or theft, and identification verification (your birth date, your mother’s maiden name, or your Social Security number—memorize this, don’t carry a copy). If you are the secondary cardholder, you’ll also need to provide the primary cardholder’s identification-verification details. You can generally receive a temporary card within two or three business days in Europe (see www.ricksteves.com/help for more).

If you report your loss within two days, you typically won’t be responsible for any unauthorized transactions on your account, although many banks charge a liability fee of $50.

Tipping (donner un pourboire) in France isn’t as automatic and generous as it is in the US. For special service, tips are appreciated, but not expected. As in the US, the proper amount depends on your resources, tipping philosophy, and the circumstances, but some general guidelines apply.

Restaurants: At cafés and restaurants, a service charge is always included in the price of what you order (service compris or prix net), but you won’t see it listed on your bill. Unlike in the US, France pays servers a decent wage. Because of this, most locals never tip (credit-card receipts don’t even have space to add a tip). If you feel the service was exceptional, it’s kind to tip up to 5 percent extra. But never feel guilty if you don’t leave a tip.

Taxis: For a typical ride, round up your fare a bit (for instance, if the fare is €13, pay €14). If the cabbie hauls your bags and zips you to the airport to help you catch your flight, you might want to toss in a little more. But if you feel like you’re being driven in circles or otherwise ripped off, skip the tip.

Services: In general, if someone in the service industry does a super job for you, a small tip of a euro or two is appropriate...but not required. If you’re not sure whether (or how much) to tip for a service, ask your hotelier or the TI.

Wrapped into the purchase price of your French souvenirs is a Value-Added Tax (VAT) of about 20 percent. You’re entitled to get most of that tax back if you purchase more than €175 (about $245) worth of goods at a store that participates in the VAT-refund scheme. Typically, you must ring up the minimum at a single retailer—you can’t add up your purchases from various shops to reach the required amount.

Getting your refund is usually straightforward and, if you buy a substantial amount of souvenirs, well worth the hassle. If you’re lucky, the merchant will subtract the tax when you make your purchase. (This is more likely to occur if the store ships the goods to your home.) Otherwise, you’ll need to:

Get the paperwork. Have the merchant completely fill out the necessary refund document, Bordereau de Vente a l’Exportation, also called a “cheque.” You’ll have to present your passport. Get the paperwork done before you leave the store to ensure you’ll have everything you need (including your original sales receipt).

Get your stamp at the border or airport. Process your VAT document at your last stop in the European Union (such as at the airport) with the customs agent who deals with VAT refunds. Arrive an additional hour early before you need to check in for your flight, to allow time to find the local customs office—and to stand in line. It’s best to keep your purchases in your carry-on. If they’re too large or dangerous to carry on (such as knives), pack them in your checked bags and alert the check-in agent. You’ll be sent (with your tagged bag) to a customs desk outside security, which will examine your bag, stamp your paperwork, and put your bag on the belt. You’re not supposed to use your purchased goods before you leave. If you show up at customs wearing your chic new shoes, officials might look the other way—or deny you a refund.

Collect your refund. You’ll need to return your stamped document to the retailer or its representative. Many merchants work with a service, such as Global Blue or Premier Tax Free, that has offices at major airports, ports, or border crossings (either before or after security, probably strategically located near a duty-free shop). At Charles de Gaulle, you’ll find them at the check-in area (or ask for help at an orange ADP info desk). These services, which extract a 4 percent fee, can refund your money immediately in cash or credit your card (within two billing cycles). If the retailer handles VAT refunds directly, it’s up to you to contact the merchant for your refund. You can mail the documents from home, or more quickly, from your point of departure (using an envelope you’ve prepared in advance or one that’s been provided by the merchant). You’ll then have to wait—it can take months.

You are allowed to take home $800 worth of items per person duty-free, once every 30 days. You can also bring in duty-free a liter of alcohol. As for food, you can take home many processed and packaged foods: vacuum-packed cheeses, dried herbs, jams, baked goods, candy, chocolate, oil, vinegar, mustard, and honey. Fresh fruits and vegetables and most meats are not allowed. However, canned meat is allowed if it doesn’t contain any beef, veal, lamb, or mutton. Any liquid-containing foods must be packed in checked luggage, a potential recipe for disaster. To check customs rules and duty rates, visit www.cbp.gov.

Sightseeing can be hard work. Use these tips to make your visits to Paris’ finest sights meaningful, fun, efficient, and painless.

Set up an itinerary that allows you to fit in all your must-see sights. For a one-stop look at opening hours, see “Paris at a Glance” (here). Remember, the Louvre and some other museums are closed on Tuesday, and many others are closed on Monday (see “Daily Reminder” on here). Most sights keep stable hours, but you can easily confirm the latest by checking their website or picking up the booklet Musées, Monuments Historiques, et Expositions, free at most museums. You can also find good information on many of Paris’ sights online at www.parisinfo.com.

Don’t put off visiting a must-see sight—you never know when a place will close unexpectedly for a holiday, strike, or restoration. Many museums are closed or have reduced hours at least a few days a year, especially on holidays such as Christmas, New Year’s, and Labor Day (May 1). A list of holidays is on here; check museum websites for possible closures during your trip. Off-season, many museums have shorter hours.

Going at the right time helps avoid crowds. This book offers tips on the best times to see specific sights. Try visiting popular sights very early (arrive at least 15 minutes before opening time) or very late. Evening visits are usually peaceful, with fewer crowds. The Louvre and Orsay museums are open selected evenings, while the Pompidou Center is open late every night except Tuesday (when it’s closed all day). Some sights stay open late in summer.

Plan to buy a Paris Museum Pass, which can speed you through lines and save you money (for pass details, see here). For information on more money-saving tips, see “Affording Paris’ Sights” on here.

Study up. To get the most out of the self-guided tours and sight descriptions in this book, read them before you visit. The Louvre is more interesting if you understand why the Venus de Milo is so disarming.

Here’s what you can typically expect:

Entering: Be warned that you may not be allowed to enter if you arrive 30 to 60 minutes before closing time. And guards start ushering people out well before the actual closing time, so don’t save the best for last.

Some important sights have a security check, where you must open your bag or send it through a metal detector. Some sights require you to check daypacks and coats. (If you’d rather not check your daypack, try carrying it tucked under your arm like a purse as you enter.) If you check a bag, the attendant may ask you if it contains anything of value—such as a camera, phone, money, passport—since these usually cannot be checked.

At churches—which often offer interesting art (usually free) and a cool, welcome seat—a modest dress code (no bare shoulders or shorts) is encouraged though rarely enforced.

Photography: If the museum’s photo policy isn’t clearly posted, ask a guard. Generally, taking photos without a flash or tripod is allowed. Some sights ban photos altogether.

Temporary Exhibits: Museums may show special exhibits in addition to their permanent collection. Some exhibits are included in the entry price, while others come at an extra cost (which you may have to pay even if you don’t want to see the exhibit).

Expect Changes: Artwork can be on tour, on loan, out sick, or shifted at the whim of the curator. To adapt, pick up a floor plan as you enter, and ask museum staff if you can’t find a particular item. Say the title or artist’s name, or point to the photograph in this book and ask for its location by saying, “Où est?” (oo ay).

Audioguides: Many sights rent audioguides, which generally offer useful recorded descriptions in English (about €6, sometimes included with admission). If you bring along your own earbuds, you can enjoy better sound and avoid holding the device to your ear. To save money, bring a Y-jack and share one audioguide with your travel partner. Increasingly, sights are offering apps (often free) that you can download to your mobile device. I’ve produced free downloadable audio tours for the Louvre, Orsay Museum, Versailles, and my Historic Paris Walk (all based on the tours in this book); see here.

Services: Important sights may have an on-site café or cafeteria (usually a handy place to rejuvenate during a long visit). The WCs at sights are free and generally clean.

Before Leaving: At the gift shop, scan the postcard rack or thumb through a guidebook to be sure that you haven’t overlooked something that you’d like to see.

Every sight or museum offers more than what is covered in this book. Use the information in this book as an introduction—not the final word.

“How can I stay connected in Europe?”—by phone and Internet—may be the most common question I hear from travelers. You have three basic options:

1. “Roam” with your US smartphone. This is the easiest option, but likely the most expensive. It works best for people who won’t be making very many calls, and who value the convenience of sticking with what’s familiar (and their own phone number). In recent years, as data roaming fees have dropped and free Wi-Fi has become easier to find, the majority of travelers are finding this to be the best all-around option.

2. Use an unlocked mobile phone with European SIM cards. This is a much more affordable option if you’ll be making lots of calls, since it gives you 24/7 access to cheap European rates. Although remarkably cheap, this option does require a willingness to grapple with the technology and do a bit of shopping around for the right phone and card. Savvy travelers who routinely use SIM cards swear by them.

3. Use public phones and get online at your hotel or at Internet cafés. These options can work in a pinch, particularly for travelers who simply don’t want to hassle with the technology, or want to be (mostly) untethered from their home life while on the road.

Each of these options is explained in greater detail in the following pages. Mixing and matching works well. For example, I routinely bring along my smartphone for Internet chores and Skyping on Wi-Fi, but also carry an unlocked phone and buy cheap SIM cards for affordable calls on the go.

For a more in-depth explanation of this topic, see www.ricksteves.com/phoning.

Many Americans are intimidated by dialing European phone numbers. You needn’t be. It’s simple, once you break the code.

The following instructions apply whether you’re dialing from a French mobile phone or a landline (such as a pay phone or your hotel-room phone). If you’re roaming with a US phone number, follow the “Dialing Internationally” directions described later.

France has a direct-dial 10-digit phone system (no area codes). To make domestic calls anywhere within France, just dial the number.

For example, the number of one of my recommended hotels in Paris (the Hôtel Relais Bosquet) is 01 47 05 25 45. That’s the number you dial whether you’re calling it from across the street or across the country.

Understand the various prefixes. All Paris landline numbers start with 01. Any number beginning with 06 or 07 is a mobile phone, and costs more to dial. France’s toll-free numbers start with 0800 (like US 800 numbers, though in France you dial a 0 first rather than a 1). In France these 0800 numbers—called numéro vert (green number)—can be dialed free from any phone without using a phone card. But you can’t call France’s toll-free numbers from America, nor can you count on reaching US toll-free numbers from France.

Any 08 number that does not have a 00 directly following is a toll call, generally costing €0.10 to €0.50 per minute.

Always start with the international access code—011 if you’re calling from the US or Canada, 00 from anywhere in Europe. If you’re dialing from a mobile phone, simply insert a + instead (by holding the 0 key).

Dial the country code of the country you’re calling (33 for France, or 1 for the US or Canada). Then dial the local number. If you’re calling France, drop the initial zero of the phone number. The European calling chart lists specifics per country.

Calling from the US to France: To call the recommended Hôtel Relais Bosquet from the US, dial 011 (US access code), 33 (France’s country code), then 1 47 05 25 45 (the hotel’s number without its initial zero).

Calling from any European country to the US: To call my office in Edmonds, Washington, from anywhere in Europe, I dial 00 (Europe’s access code), 1 (US country code), 425 (Edmonds’ area code), and 771-8303.

The chart on here shows how to dial per country. For online instructions, see www.countrycallingcodes.com or www.howtocallabroad.com.

Remember, if you’re using a mobile phone, dial as if you’re in that phone’s country of origin. So, when roaming with your US phone number in France, dial as if you’re calling from the US. But if you’re using a European SIM card, dial as you would from that European country.

Note that calls to a European mobile phone are substantially more expensive than calls to a fixed line. Off-hour calls are generally cheaper.

For tips on communicating over the phone with someone who speaks another language, see here.

Even in this age of email, texting, and near-universal Internet access, smart travelers still use the telephone. I call TIs to smooth out sightseeing plans, hotels to get driving directions, museums to confirm tour schedules, restaurants to check open hours or to book a table, and so on.

Most people enjoy the convenience of bringing their own smartphone. Horror stories about sky-high roaming fees are dated and exaggerated, and major service providers work hard to avoid surprising you with an exorbitant bill. With a little planning, you can use your phone—for voice calls, messaging, and Internet access—without breaking the bank.

Start by figuring out whether your phone works in Europe. Most phones purchased through AT&T and T-Mobile (which use the same technology as Europe) work abroad, while only some phones from Verizon or Sprint do—check your operating manual (look for “tri-band,” “quad-band,” or “GSM”). If you’re not sure, ask your service provider.

“Roaming” with your phone—that is, using it outside of its home region, such as in Europe—generally comes with extra charges, whether you are making voice calls, sending texts, or reading your email. The fees listed here are for the three major American providers—Verizon, AT&T, and T-Mobile; Sprint’s roaming rates tend to be much higher. But policies change fast, so get the latest details before your trip. For example, as of mid-2014, T-Mobile waived voice, texting, and data roaming fees for some plans.

Voice calls are the most expensive. Most providers charge from $1.29 to $1.99 per minute to make or receive calls in Europe. (As you cross each border, you’ll typically get a text message explaining the rates in the new country.) If you plan to make multiple calls, look into a global calling plan to lower the per-minute cost, or buy a package of minutes at a discounted price (such as 30 minutes for $30). Note that you’ll be charged for incoming calls whether or not you answer them; to save money ask your friends to stay in contact by texting, and to call you only in case of an emergency.

Text messaging costs 20 to 50 cents per text. To cut that cost, you could sign up for an international messaging plan (for example, $10 for 100 texts). Or consider apps that let you text for free (iMessage for Apple, Google Talk for Android, or WhatsApp for any device); however, these require you to use Wi-Fi or data roaming. Be aware that Europeans use the term “SMS” (“short message service”) to describe text messaging.

Data roaming means accessing an Internet signal that’s carried over the cellular telephone network. Prices have dropped dramatically in recent years, making this an affordable way to bridge gaps between Wi-Fi hotspots. You’ll pay far less if you set up an international data roaming plan. Most providers charge $25-30 for 100-120 megabytes of data. That’s plenty for basic Internet tasks—100 megabytes lets you view 100 websites or send/receive 1,000 text-based emails, but you’ll burn through that amount quickly by streaming videos or music. If your data use exceeds your plan amount, most providers will automatically kick in an additional 100- or 120-megabyte block for the same price. (For more on Wi-Fi versus data roaming—including strategies for conserving your data—see “Using Wi-Fi and Data Roaming,” later.)

With most service providers, international roaming (voice, text, and data) is disabled on your account unless you call to activate it. Before your trip, call your provider (or navigate their website), and cover the following topics:

• Confirm that your phone will work in Europe.

• Verify global roaming rates for voice calls, text messaging, and data roaming.

• Tell them which of those services you’d like to activate.

• Consider any add-on plans to bring down the cost of international calls, texts, or data roaming.

When you get home from Europe, be sure to cancel any add-on plans that you activated for your trip.

Some people would rather use their smartphone exclusively on Wi-Fi, and not worry about either voice or data charges. If that’s you, call your provider to be sure that international roaming options are deactivated on your account. To be double-sure, put your phone in “airplane mode,” then turn your Wi-Fi back on.

A good approach is to use free Wi-Fi wherever possible, and fill in the gaps with data roaming.

Wi-Fi (sometimes called “WLAN”)—Internet access through a wireless router—is readily available throughout Europe. But just like at home, the quality of the signal may vary. Be patient, and don’t get your hopes up. At accommodations, access is often free, but you may have to pay a fee, especially at expensive hotels. At hotels with thick stone walls, the Wi-Fi router in the lobby may not reach every room. If Wi-Fi is important to you, ask about it when you book—and be specific (“in the rooms?”). Get the password and network name at the front desk when you check in.

When you’re out and about, your best bet for finding free Wi-Fi is often at a café. They’ll usually tell you the password if you buy something. Or you can stroll down a café-lined street, smartphone in hand, checking for unsecured networks every few steps until you find one that works. Some towns have free public Wi-Fi in highly trafficked parks or piazzas. You may have to register before using it, or get a password at the TI. For more on where to find free Wi-Fi in Paris, see here.

Data roaming—that is, accessing the Internet through the cellular network—is handy when you can’t find useable Wi-Fi. Because you’ll pay by the megabyte (explained earlier), it’s best to limit how much data you use. Save bandwidth-gobbling tasks like Skyping, watching videos, or downloading apps or emails with large attachments until you’re on Wi-Fi. Switch your phone’s email settings from “push” to “fetch.” This means that you can choose to “fetch” (download) your messages when you’re on Wi-Fi rather than having them continuously “pushed” to your device. And be aware of apps—such as news, weather, and sports tickers—that automatically update. Check your phone’s settings to be sure that none of your apps is set to “use cellular data.”

I like the safeguard of manually turning off data roaming on my phone whenever I’m not actively using it. To turn off data and voice roaming, look in your phone’s menu—try checking under “cellular” or “network,” or ask your service provider how to do it. If you need to get online but can’t find Wi-Fi, simply turn on data roaming long enough for the task at hand, then turn it off again.

Figure out how to keep track of how much data you’ve used (in your phone’s menu, look for “cellular data usage”; you may have to reset the counter at the start of your trip). Some companies automatically send you a text message warning if you approach or exceed your limit.

There’s yet another option: If you’re traveling with an unlocked smartphone (explained later), you can buy a SIM card that also includes data; this can be far, far cheaper than data roaming through your home provider.

Using your American phone in Europe is easy, but it’s not always cheap. And unreliable Wi-Fi can make keeping in touch frustrating. If you’re reasonably technology-savvy, and would like to have the option of making lots of affordable calls, it’s worth getting comfortable with European SIM cards.

Here’s the basic idea: First you need an unlocked phone that works in Europe. Then, in Europe, shop around for a SIM card—the little data chip that inserts into your phone—to equip it with a European number. Turn on the phone, and bingo! You’ve got a European phone number (and access to cheaper European rates).

Your basic options are getting your existing phone unlocked, or buying a phone (either at home or in Europe).

Some phones are electronically “locked” so that you can’t switch SIM cards (keeping you tied to your original service provider). But it’s possible to “unlock” your phone—allowing you to replace the original SIM card. An unlocked phone is versatile; not only does it work with any European provider, but many US providers now offer no-contract, prepaid (or “pay-as-you-go”) alternatives that work with SIM technology.

You may already have an old, unused mobile phone in a drawer somewhere. Call your service provider and ask if they’ll send you the unlock code. Otherwise, you can buy one: Search an online shopping site for an “unlocked quad-band phone,” or buy one at a mobile-phone shop in Europe. Either way, a basic model typically costs $40 or less.

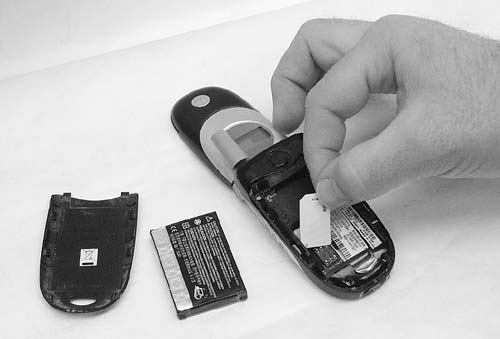

Once you have an unlocked phone, you’ll need to buy a SIM card—a small, fingernail-size chip that stores your phone number and other information. (A smaller variation called “micro-SIM” or “nano-SIM” cards—used in most iPhones—are less widely available.)

SIM cards are sold at mobile-phone shops, department-store electronics counters, and newsstands for $5–10, and usually include about that much prepaid calling credit (making the card itself virtually free). Because SIM cards are prepaid, there’s no contract and no commitment; I routinely buy one even if I’m in a country for only a few days.

However, an increasing number of countries—including France—require you to register the SIM card with your passport (an antiterrorism measure). This takes only a few minutes longer: The shop clerk will ask you to fill out a form, then submit it to the service provider. Sometimes you can register your own SIM card online. Either way, an hour or two after submitting the information, you’ll get a text welcoming you to that network.

When using a SIM card in its home country, it’s free to receive calls and texts, and it’s cheap to make calls—domestic calls average 20 cents per minute. You can also use SIM cards to call the US—sometimes very affordably (Lebara and Lycamobile, which operate in multiple European countries, let you call a US number for less than 10 cents a minute). Rates are higher if you’re roaming in another country. But if you bought the SIM card within the European Union, roaming fees are capped no matter where you travel throughout the EU (about 25 cents/minute to make calls, 7 cents/minute to receive calls, and 8 cents for a text message).

While you can buy SIM cards just about anywhere, I like to seek out a mobile-phone shop, where an English-speaking clerk can help explain my options, get my SIM card inserted and set up, and show me how to use it. When you buy your SIM card, ask about rates for domestic and international calls and texting, and about roaming fees. Also find out how to check your credit balance (usually you’ll key in a few digits and hit “Send”). You can top up your credit at any newsstand, tobacco shop, mobile-phone shop, or many other businesses (look for the SIM card’s logo in the window).

To insert your SIM card into the phone, locate the slot, which is usually on the side of the phone or behind the battery. Turning on the phone, you’ll be prompted to enter the “SIM PIN” (a code number that came with your card).

If you have an unlocked smartphone, you can look for a European SIM card that covers both voice and data. This is often much cheaper than paying for data roaming through your home provider.

If you prefer to travel without a smartphone or tablet, you can still stay in touch using landline telephones, hotel guest computers, and Internet cafés.

Phones in your hotel room can be great for local calls and for calls using cheap international phone cards (described in the sidebar). Many hotels charge a fee for local and “toll-free” as well as long-distance or international calls—always ask for the rates before you dial. Since you’ll never be charged for receiving calls, it can be more affordable to have someone from the US call you in your room.

While public pay phones are on the endangered species list, you’ll still see them in post offices and train stations. Pay phones generally come with multilingual instructions. Most public phones work with insertable phone cards (described in the sidebar).

You’ll see many cheap call shops that advertise low rates to faraway lands, often in train-station neighborhoods. While these target immigrants who want to call home cheaply, tourists can use them, too. Before making your call, be completely clear on the rates.

Finding public Internet terminals in Europe is no problem. Many hotels have a computer in the lobby for guests to use. Otherwise, head for an Internet café, or ask the TI or your hotelier for the nearest place to access the Internet.

European computers typically use non-American keyboards. A few letters are switched around, and command keys are labeled in the local language. Many European keyboards have an “Alt Gr” key (for “Alternate Graphics”) to the right of the space bar; press this to insert the extra symbol that appears on some keys. French keyboards are a little different from ours; to type an @ symbol, press the “Alt Gr” key and “à/0” key. If that doesn’t work, simply copy it (Ctrl-C) from a Web page and paste it (Ctrl-V) into your email message.

Whether you’re accessing the Internet with your own device or at a public terminal, using a shared network or computer comes with the potential for increased security risks. Ask the hotel or café for the specific name of their Wi-Fi network, and make sure you log on to that exact one; hackers sometimes create a bogus hotspot with a similar or vague name (such as “Hotel Europa Free Wi-Fi”). It’s better if a network uses a password (especially a hard-to-guess one) rather than being open to the world.

While traveling, you may want to check your online banking or credit-card statements, or to take care of other personal-finance chores, but Internet security experts advise against accessing these sites entirely while traveling. Even if you’re using your own computer at a password-protected hotspot, any hacker who’s logged on to the same network can see what you’re up to. If you need to log on to a banking website, try to do so on a hard-wired connection (i.e., using an Ethernet cable in your hotel room), or if that’s not possible, use a secure banking app on a cellular telephone connection.

If using a credit card online, make sure that the site is secure. Most browsers display a little padlock icon, and the URL begins with https instead of http. Never send a credit-card number over a website that doesn’t begin with https.

If you’re not convinced a connection is secure, avoid accessing any sites (such as your bank’s) that could be vulnerable to fraud.

You can mail one package per day to yourself worth up to $200 duty-free from Europe to the US (mark it “personal purchases”). If you’re sending a gift to someone, mark it “unsolicited gift.” For details, visit www.cbp.gov and search for “Know Before You Go.”

The French postal service works fine, but for quick transatlantic delivery (in either direction), consider services such as DHL (www.dhl.com). French post offices are referred to as La Poste or sometimes the old-fashioned PTT, for “Post, Telegraph, and Telephone.” Hours vary, though most are open weekdays 8:00-19:00 and Saturday morning 8:00-12:00. Stamps and phone cards are also sold at tabacs. It costs about €1 to mail a postcard to the US. One convenient, if expensive, way to send packages home is to use the post office’s Colissimo XL postage-paid mailing box. It costs €43-53 to ship boxes weighing 5-7 kilos (about 11-15 pounds).

WICE offers a variety of well-run short- and longer-term classes in English on art, wine, food, and more (joining fee required, 10 Rue Tiphaine, near Ecole Militaire and Champs de Mars park, Mo: Dupleix or La Motte Picquet Grenelle, buses #80 and #42, tel. 01 45 66 75 50, www.wice-paris.org).

Alliance Francaise has the best reputation and good variety of courses, but also the highest rates; can also help with accommodations (101 Boulevard Raspail, tel. 01 42 84 90 00, www.alliancefr.org).

Ecole France Langue provides intensive classes on a weekly basis with business-language options (tel. 01 45 00 40 15 or 01 42 66 18 08, www.france-langue.fr).

Le Français Face à Face runs intensive French courses with total immersion and full-board options in the town of Angers, in the Loire Valley (tel. 06 66 60 00 63, www.lefrancaisfaceaface.com).

Le Cordon Bleu has pricey demonstration courses (tel. 01 53 68 22 50, www.lcbparis.com).

These schools are more relaxed:

La Cuisine Paris has a great variety of classes in English, reasonable prices, and a beautiful space in central Paris (2- or 3-hour classes-€65-95, 4-hour class with market tour-€150, gourmet visit of Versailles—see website for details, 80 Quai de l’Hôtel de Ville, tel. 01 40 51 78 18, www.lacuisineparis.com).

Cook’n with Class gets rave reviews for its convivial cooking and wine-and-cheese classes with a maximum of six students; tasting courses offered as well (6 Rue Baudelique, Mo: Jules Joffrin or Simplon, tel. 06 31 73 62 77, www.cooknwithclass.com).

Susan Herrmann Loomis, an acclaimed chef and author, offers cooking courses in Paris or at her home in Normandy. Your travel buddy can skip the class but come for the meal at a reduced “guest eater” price (www.onruetatin.com).

Edible Paris, run by Friendly Canadian Rosa Jackson, puts together personalized “foodie” itineraries and preset three-hour “food guru” tours of Paris (www.edible-paris.com).

Paris By Mouth offers fun and frequent food-centric tours and tastings—choose by location or flavor (€95 for 3 hours, includes tastings, www.parisbymouth.com).

Les Secrets Gourmands de Noémie, where charming and knowledgeable Noémie shares her culinary secrets, provides 2.5 hours of hands-on fun in the kitchen. Thursday classes, designed for English speakers, focus on sweets; classes on other days are in French, English, or both depending on the participants, and tackle savory dishes with the possibility for an add-on pre-class market tour (€75-105, 92 Rue Nollet, Mo: La Fourche, tel. 06 64 17 93 32, www.lessecretsgourmandsdenoemie.com, noemie@lessecretsgourmandsdenoemie.com).

I like the friendly sommeliers of Ô Château (see here for listing).

While I don’t recommend it, you could arrange longer day trips from Paris to places around northern France, such as the Loire Valley, Burgundy, Mont St-Michel, and the D-Day beaches of Normandy (all beyond the scope of this book, but well-covered in Rick Steves France). Thanks to bullet trains and good local guides who can help you maximize your time, well-coordinated blitz-tour trips to these places are doable, though hardly relaxing. If you do want to see these places in a day, I recommend using a guide from the region who will meet you at the train station (most have cars) and spend the day showing you their region’s highlights before making sure you get on your return train to Paris. Book well in advance, though last-minute requests can work out.

Loire Valley: Pascal Accolay runs Acco-Dispo, which offers good all-day château tours from the cities of Tours or Amboise (from Tours: €22/half-day, €54/day, more if from Amboise; daily, tel. 06 82 00 64 51, www.accodispo-tours.com).

Burgundy: For tours that focus on vineyards, contact Colette Barbier (€235/half-day, €390/day, tel. 03 80 23 94 34, mobile 06 80 57 47 40, www.burgundy-guide.com, cobatour@aol.com) or delightful Brit Stephanie Jones (price per person: €95/half-day, €180/day, 2-person minimum, mention this book for preferable rate, tel. 03 80 61 29 61, mobile 06 10 18 04 12, www.aux-quatre-saisons.net, aux4saisons35@aol.com).

Mont St-Michel and Brittany: Westcapades runs day-long minivan tours covering St-Malo and Mont St-Michel (€95/day, tel. 02 96 39 79 52, www.westcapades.com, marc@westcapades.com).

D-Day Beaches by Minivan Tour: An army of small companies offers all-day excursions to the D-Day beaches from Bayeux or Caen for about €90 per person, or about €475-500 for groups of up to eight, or about €350 to join you in your car (most don’t visit museums, but those that do usually include entry fees—ask). Paul de Winter has a PhD in military history, making history buffs happy (www.dewintertours.com). Normandy Battle Tours are led by Stuart Robertson, a gentle Brit who loves teaching visitors about the landings (tel. 02 33 41 28 34, www.normandybattletours.com, enquiries@normandybattletours.com). Victory Tours offers informal and entertaining tours led by friendly Dutchman Roel (departs from Bayeux only, tel. 02 31 51 98 14, www.victorytours.com, victorytours@orange.fr). Bayeux Shuttle works well for individuals and offers Bayeux pick-up. Their good website has an easy sign-up calendar (tel. 06 59 70 72 55, www.bayeuxshuttle.com). The Caen Memorial Museum’s “D-Day Tour” package is designed for day-trippers and includes pickup from the Caen train station (with frequent service from Paris), a guided tour through the WWII exhibits at the Memorial Museum, lunch, and then a five-hour afternoon tour in English (and French) of the major Anglo-Canadian beaches. Your day ends with a drop-off at the Caen train station in time to catch a train back to Paris or elsewhere (€120, includes English information book, tel. 02 31 06 06 44—as in June 6, 1944, www.memorial-caen.fr).

Rick Steves Paris 2015 is one of many books in my series on European travel, which includes country guidebooks (including France), city guidebooks (Rome, Florence, London, etc.), regional guides (including Provence and the French Riviera), Snapshot guides (excerpted chapters from my country guides), Pocket Guides (full-color little books on big cities, including Paris), and my budget-travel skills handbook, Rick Steves’ Europe Through the Back Door. Most of my titles are available as ebooks. My phrase books—for French, Italian, German, Spanish, and Portuguese—are practical and budget-oriented. My other books include Europe 101 (a crash course on art and history designed for travelers); Mediterranean Cruise Ports and Northern European Cruise Ports (how to make the most of your time in port); and Travel as a Political Act (a travelogue sprinkled with tips for bringing home a global perspective). A more complete list of my titles appears near the end of this book.

Video: My public television series, Rick Steves’ Europe, covers European destinations in 100 shows, with 10 episodes on France. To watch full episodes online for free, see www.ricksteves.com/tv. Or to raise your travel I.Q. with video versions of our popular classes, see www.ricksteves.com/travel-talks.

Audio: My weekly public radio show, Travel with Rick Steves, features interviews with travel experts from around the world. I’ve also produced free, self-guided audio tours of the top sights in Paris. All of this audio content is available for free at Rick Steves Audio Europe, an extensive online library organized by destination. Choose whatever interests you, and download it for free via the Rick Steves Audio Europe smartphone app, www.ricksteves.com/audioeurope, iTunes, or Google Play.

The black-and-white maps in this book are concise and simple, designed to help you locate recommended places and get to local TIs, where you can pick up more in-depth maps of cities and regions (usually free).

Though Paris is littered with free maps, they don’t show all the streets. For an extended stay, I prefer the pocket-size, street-indexed Paris Pratique or Michelin’s Paris par Arrondissement (each about €6, sold at newsstands and bookstores in Paris). Streetwise Paris maps are popular, as they are rainproof and indestructible (about $8 in the US, www.streetwisemaps.com). I also like the City Maps 2Go app (available from iTunes), which has good, searchable maps even when you’re not online. Before you buy a map, look at it to be sure it has the level of detail you want.

To learn more about Paris past and present, check out a few of these books or films.

How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City (Joan DeJean) describes Paris’ emergence from the Dark Ages into the world’s grandest city. For a better understanding of French politics, culture, and people, check out Sixty Million Frenchmen Can’t Be Wrong (Nadeau and Barlow), Culture Shock: France (Taylor), French or Foe, and Savoir-Flair! (both by Polly Platt). The Course of French History (Goubert) provides a basic summary of French history, while The Cambridge Illustrated History of France (Jones) comes with coffee-table-book pictures and illustrations. La Seduction: How the French Play the Game of Life (Sciolino) explains how seduction has long been used in all aspects of French life, from small villages to the halls of government, providing a surprisingly helpful cultural primer.

A Moveable Feast is Ernest Hemingway’s classic memoir of 1920s Paris. In I’ll Always Have Paris, Art Buchwald meets Hemingway, among others. Suite Française (Nemirovsky) is by a Jewish writer who eloquently describes how life changed after the Nazi occupation. Is Paris Burning? (Collins) brings late-WWII Paris to life on its pages. Americans in Paris: Life and Death under Nazi Occupation is a fascinating read (Glass). Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light (Stovall) explains why African Americans found Paris so freeing in the first half of the 20th century.

Paris to the Moon is Adam Gopnik’s charming collection of stories about life as a New Yorker in Paris (his literary anthology, Americans in Paris, is also recommended). A Corner in the Marais (Karmel) is a detailed account of one Parisian neighborhood; Diane Johnson’s Into a Paris Quartier tells tales about the sixth arrondissement. The memoir The Piano Shop on the Left Bank (Carhart) captures Paris’ sentimental appeal. Almost French (Turnbull) is a funny take on living as a Parisian native. Reading The Flâneur is like wandering with author Edmund White through his favorite finds. A mix of writers explores Parisian culture in Travelers Tales: Paris (O’Reilly).

The Authentic Bistros of Paris (Thomazeau), a pretty picture book, will have you longing for a croque monsieur. The Sweet Life in Paris (Lebovitz) is funny and articulate, and delivers oodles of food suggestions for travelers in Paris. Foodies seek out the most complete (and priciest) menu reader around: A to Z of French Food, a French to English Dictionary of Culinary Terms (G. de Temmerman).

Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities shows the pathos and horror of the French Revolution, as does Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables (his The Hunchback of Notre-Dame is also set in Paris).

The anthology A Place in the World Called Paris (Barclay) includes essays by literary greats from Truman Capote to Franz Kafka. The characters in Marge Piercy’s City of Darkness, City of Light storm the Bastille. And though it relies on some stereotypes, A Year in the Merde (Clarke) is a lighthearted look at life as a faux Parisian.

Georges Simenon was a Belgian, but he often set his Inspector Maigret detective series in Paris; The Hotel Majestic is particularly good. Mystery fans should also consider Murder in Montparnasse (Engel), Murder in the Marais (Black), and Sandman (Janes), set in Vichy-era Paris. Alan Furst writes gripping novels about WWII espionage that put you right into the action in Paris.

For children, there’s the beloved Madeline series (Bemelmans), where “in an old house in Paris that was covered with vines, lived twelve little girls in two straight lines.” Kids of all ages enjoy the whimsical and colorful impressions of the city in Miroslav Sasek’s classic picture-book This Is Paris. For more ideas, see the kids’ reading list on here.

Children of Paradise (1946), a melancholy romance, was filmed during the Nazi occupation of Paris. In The Red Balloon (1956), a small boy chases his balloon through the city streets, showing how beauty can be found even in the simplest toy. The 400 Blows (1959) and Jules and Jim (1962) are both classics of French New Wave cinema by director François Truffaut. Charade (1963) combines a romance between Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant with a crime story.

Blue/White/Red (1990s) is a stylish trilogy of films, each featuring a famous French actress as the lead (Blue, with Juliette Binoche, is the best of the three). Ridicule (1996), set in the opulent court of Louis XVI, shows that survival depended on a quick wit and an acid tongue. In the crime caper Ronin (1998), Robert De Niro and Jean Reno lead a car chase through the city.

Moulin Rouge! (2001) is a fanciful musical set in the legendary Montmartre night club. Amélie (2001), a crowd-pleasing romance, features a charming young waitress searching for love and the meaning of life. La Vie en Rose (2007) covers the glamorous and turbulent life of singer Edith Piaf, who famously regretted nothing (many scenes were shot in Paris). No Disney flick, The Triplets of Belleville (2003) is a surreal-yet-heartwarming animated film that begins in a very Parisian fictional city.

For over-the-top, schlocky fun, watch The Phantom of the Opera (2004), about a disfigured musical genius hiding in the Paris Opera House, and The Da Vinci Code (2006), a blockbuster murder mystery partly filmed inside the Louvre.

Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris (2011) is a sharp comedy that shifts between today’s Paris and the 1920s mecca of Picasso, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald. If you’ll be heading to Versailles, try Marie Antoinette (2006), a delicate little bonbon of a film about the misunderstood queen.

To get the French perspective on world events and to learn what’s making news in France, find France 24 News online at www.France24.com/en.