I. The Formation of the Legend

BY THE TIME that the T’ang dynasty had gained control of a unified China in 618, Buddhism was already firmly entrenched on Chinese soil. From its modest beginnings as a religion introduced by traveling merchants and both Indian and Central Asian missionaries in the first and second centuries, it had spread throughout all levels of Chinese society. Vast temple complexes, awe-inspiring in their magnificence, stood in the cities and towns; great monastic communities graced the top of many a lofty mountain. Imposing works of sculpture and painting and an elaborate and ornate ritual stirred the hearts and minds of the populace. The enormous body of Buddhist literature was, over the centuries, translated into Chinese. Native priests of great genius emerged, to explain, to systematize, and to adapt Buddhist teaching to Chinese ways of thinking. Great centers of learning arose, specializing in specific branches of Buddhist thought.

Buddhism had spread in China, despite the attacks of its Confucian and Taoist opponents. It had weathered several persecutions and had emerged stronger each time. Gradually Buddhism had adapted itself to the Chinese milieu, and had acclimated itself to the extent that new, sinified forms were beginning to appear. Throughout Buddhism’s history, emperors of various dynasties had accepted its teachings and had, in many ways, used Buddhism to further their own causes. The T’ang was no exception. Although the founder of the T’ang was nominally a Taoist, he not only did not interfere with the continued rise of Buddhism; in fact he contributed much to it. Succeeding emperors, and especially the Empress Wu, were devout Buddhists. Buddhist ceremonies were adopted as an integral part of court ritual. China, by the eighth century, was virtually a Buddhist nation.

Some opposition did indeed exist: Confucianists continued to complain and memorialize against this religion that was so contrary to the traditional political and moral concepts they upheld; Taoists, shorn of their importance, resented the loss of power and respect for their beliefs. At times these voices of protest managed to gain a hearing. Occasionally during the T’ang dynasty, a particular emperor might favor the cause of the antagonists of Buddhism, but in most instances his successor soon restored whatever prerogatives the previous reign had seen fit to take away. But the imperial acceptance of Buddhism, while often blindly enthusiastic, was tempered by the realization that some restraints were necessary. There was, to a certain degree, a control maintained over the proliferation of temples; there were regulations concerning the number of monks and nuns who might join the monastic communities, as well as certain qualifications for entering the calling that had to be met; and the size of tax-free temple estates was regulated. However, as time and the T’ang dynasty wore on, these regulations came more and more to be ignored. Eventually, during the declining years of the T’ang dynasty, the disastrous persecutions of the Hui-ch’ang era (842–845) took place. Buddhism survived, but it was never to regain the dominant position it had once enjoyed.

In the early years of the T’ang the Chinese attitude toward the Buddhist religion was highly eclectic. A variety of schools, each centering on certain teachings or particular canonical works, flourished. Cults, addressing their faith to specific Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, gained wide popularity. The imperial court played no particular favorites—learned priests and teachers, advocating a variety of doctrines, were accorded equally the highest of honors. The high officials who patronized them, the literary figures who wrote their praises, did not necessarily confine themselves to one school or branch of Buddhism, but felt free to sample the great variety of teachings that Buddhism had to offer.

The Buddhist schools themselves, however, were not so unworldly as to neglect to champion the advantages of their own teachings. By the middle of the eighth century we find that internecine quarrels among various Buddhist groups had greatly intensified. Works attacking rival doctrines began to appear, contributing much to the development of sectarian Buddhism. The great T’ien-t’ai school of early T’ang lost its vitality; the Chen-yen teaching of the esoteric doctrines failed to fulfill the promise of its great T’ang masters. Ch’an, and to a lesser extent the Pure Land teachings, came to hold a dominant position. The persecution of the Hui-ch’ang era served as a death blow to many of the T’ang schools. Partly out of historical circumstance and partly because of the nature of its teachings, Ch’an emerged as the primary school of Chinese Buddhism.

In the following pages I concern myself with the history of Ch’an Buddhism. Although they do not enter into the discussion, other schools and teachings, particularly in early T’ang, were of considerable importance. Long before Ch’an made its mark on Japanese soil, other T’ang schools had been imported into that island nation. There some of these teachings developed into major sects, far outdistancing the importance that they had held in T’ang China.

When Buddhism was first introduced to China, many Indian works on meditation techniques were translated and gained fairly wide circulation. Meditation had always been an essential part of Indian Buddhism and it was no less important in China. As the new religion spread and gained adherents, meditation techniques were adopted and put to use by the various schools of Buddhism; but the emphasis which was accorded them differed with each school. Eventually there came to be practitioners who devoted themselves almost exclusively to meditation. Contemporary records of them are scant1 and little is known of what they taught. Probably originally wandering ascetics, some of them began to gain a following, and eventually communities of monks were established, where the practitioners meditated and worked together. Toward the end of the seventh century one such community, that of the priest Hung-jen,2 of the East Mountain,3 had gained considerable prominence. Hung-jen, or the Fifth Patriarch, as he later came to be known, had a great number of disciples who left their Master at the completion of their training, moved to various areas of the nation, and established schools of their own. It is with these men that the story of Ch’an as a sect begins.

Once Ch’an began to be organized into an independent sect, it required a history and a tradition which would provide it with the respectability already possessed by the longer-established Buddhist schools. In the manufacture of this history, accuracy was not a consideration; a tradition traceable to the Indian Patriarchs was the objective. At the same time that Ch’an was providing itself with a past which accommodated itself to Buddhism as a whole, various competing Ch’an Masters, each with his own disciples and methods of teaching, strove to establish themselves. Throughout the eighth century a twofold movement took place: the attempt to establish Ch’an as a sect within the Buddhist teaching in general, and the attempt to gain acceptance for a particular school of Ch’an within the Chinese society in which it existed. Obviously, the first step to be taken was for each group within Ch’an to establish a history for itself. To this end, they not only perpetuated some of the old legends, but also devised new ones, which were repeated continuously until they were accepted as fact. Indeed, in the eyes of later viewers the two are virtually indistinguishable. These legends were, in most instances, not the invention of any one person, but rather the general property of the society as a whole. Various priests used various legends; some were abandoned, some adopted, but for the most part they were refined and adjusted until a relatively palatable whole emerged. To achieve the aura of legitimacy so urgently needed, histories were compiled, tracing the Ch’an sect back to the historical Buddha, and at the same time stories of the Patriarchs in China were composed, their teachings outlined, their histories written, and their legends collected. Treatises were manufactured to which the names of the Patriarchs, the heroes of Ch’an, were attached, so as to lend such works the dignity and the authority of the Patriarch’s name.

Owing to the fragmentary condition of the literary remains of the period, to serious doubts about the authenticity of much of what is left, and to the absence of supporting historical evidence, it is virtually impossible to determine the actual process whereby Ch’an developed. Thus the story is a negative one; one can come to no definite conclusions. The legend, as it has come down to us in the Ch’an histories, is a pretty one; it makes a nice tale, but it is almost certainly untrue. The few facts that are known can, perhaps, also be molded into a nice story, but it is one surrounded by doubts, lacunae, and inconsistencies. Alleged occurrences may be denied because there is no evidence to support them, but at the same time there is little to prove that these events did not happen. This is so of the history of Ch’an in the eighth century; it is so of the story of Hui-neng, the Sixth Patriarch; and it is true as well of the book that purports to give his history and his teachings: the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch.

Yet, by examining the growth of the legends in the light of the histories of the time, by considering them in relation to the facts that are known, we may be able to learn something of the history of Ch’an in the eighth century. At least we should be able to learn what parts of it can and what parts of it cannot be accepted with any degree of assurance.

It goes without saying that no history of Ch’an in this period can be undertaken without reference to the documents discovered at Tun-huang. It is this material, discovered at the turn of this century in a sealed cave in Central Asia, which first provided evidence to controvert the entrenched legendary history of Ch’an.

The first of these documents to concern us is a Ch’an history, the Ch’uan fa-pao chi.4 Although undated, it can, through internal evidence, be placed in the first decade of the eighth century,5 and represents the history of Ch’an as it was conceived of in one particular school. It does not necessarily begin the legend, but it represents an early version of it, drawing from the existing tradition those elements which fit its purposes best. Tu Fei,6 of whom virtually nothing is known, is given as the compiler. A brief work, it contains a short preface and then presents brief biographies of the Patriarchs in China. References to and quotations from the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra demonstrate that the school which the Ch’uan fa-pao chi represents concentrated its teachings on this sutra. In the preface one finds the first evidence of an attempt to connect the Chinese Ch’an masters with the Patriarchs in India. The authority drawn upon is the Ta-mo-to-lo ch’an ching,7 a work of uncertain origin, whose preface and text mention several Indian Patriarchs. This sutra is frequently cited in later Ch’an histories to prove the legitimacy of the Ch’an tradition. At this time the T’ient’ai school had an established lineage, going back to the historical Buddha and maintaining that the Faith had been handed down from Patriarch to Patriarch until it reached Siṁha bhikṣu, the twenty-fourth, who was killed during a persecution of Buddhism, after which time the transmission was cut off.8 T’ien-t’ai traces itself by a separate lineage to Nāgārjuna, the Fourteenth Partriarch. Thus Ch’an efforts were turned towards proving that the teaching had, in fact, not been cut off, but that Siṁha bhikṣu, before his death, had passed his teaching on to a disciple. In this way Ch’an was attempting to establish that the Faith had indeed been handed down directly from Patriarch to Patriarch until it reached China. The setting-up of a patriarchal tradition both within Buddhism and within Ch’an itself, was the concern of most Ch’an histories of the eighth century. The compiler of the Ch’uan fa-pao chi did not attempt to establish a direct link with the historical Buddha; he did, however, suggest one. There is no way of determining whether this work reflects an entirely new departure or an attempt to associate Ch’an with the Indian Patriarchs, or whether it serves merely as our earliest record of certain contemporary beliefs and legends. That a variety of legends relating to the early Chinese Patriarchs did exist at this time is indicated by the compiler. In his preface he states that his account pays strict attention to authenticity, and that he rejects the mysterious legends associated with these Patriarchs.

After the preface which mentions the Indian Patriarchs, the Ch’uan fa-pao chi now turns to the transmission as seen in China. Presented are brief biographies of seven Patriarchs: Bodhidharma, Hui-k’o, Seng-ts’an, Tao-hsin, Hung-jen, Fa-ju, and Shen-hsiu. The text, unlike later works, does not assign numerical designations to these men, nor does it refer to them specifically as Patriarchs, although a successive transmission of the teaching is indicated. The first five men listed are the traditional Patriarchs of Ch’an; at no time did the sect ever question the legitimacy of their position. By the beginning of the eighth century, then, the legend of the succession of these Patriarchs was firmly entrenched. Their biographies, the stories about them, the legends which are found in later histories were, however, by no means fixed. These were first recorded, expanded, and systematized during the eighth century; they form a part of the evolution of the Ch’an legend. While the Ch’uan fa-pao chi represents this legend as known in only one particular school in the early years of the eighth century, it reveals to a certain extent the degree to which the legend had evolved by this time.

The biographies are, generally, uncomplicated; their subjects are still shadowy figures, unadorned, for the most part, with the fanciful stories and pseudofactual detail added later to bring both emotional appeal and authenticity to their characters. The account of Bodhidharma9 is a simple one: he was a Brahman from southern India who came by sea to China to propagate Buddhism. At Sung-shan10 he acquired two disciples, Tao-yü and Hui-k’o. The latter stayed with him for four or five years and received from him the teachings of the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra. The text then makes brief mention of the tale in which Hui-k’o cuts off his arm to attest to the earnestness with which he sought the teachings, and adds a note denying the allegation that Hui-k’o’s arm had been cut off by bandits.11 In a note to his own text, Tu Fei mentions Bodhidharma’s teachings of wall-gazing and the four categories of conduct,12 and comments to the effect that these are only temporary and provisional teachings and are by no means to be considered firstrate treatises. The biographical notice goes on to state that several attempts were made to poison Bodhidharma, but they were all unsuccessful, for he was immune to harm. We are told then, however, that in the end Bodhidharma did eat poison and die, and that at the time he himself claimed to be a hundred and fifty years of age. Now Tu Fei, despite the claims for the rejection of legendary material that he makes in his preface, tells us the following story:

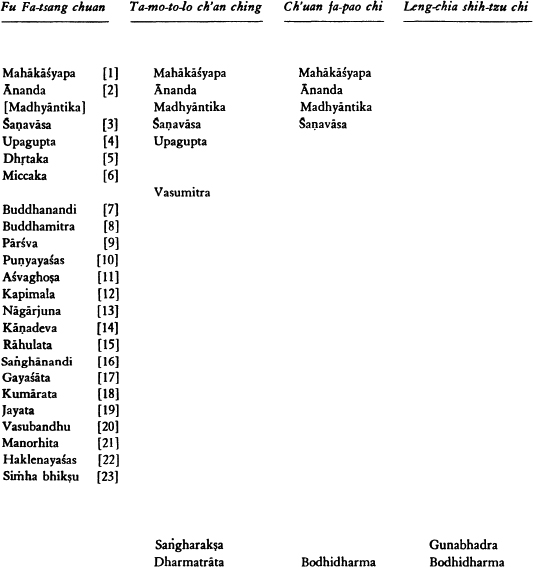

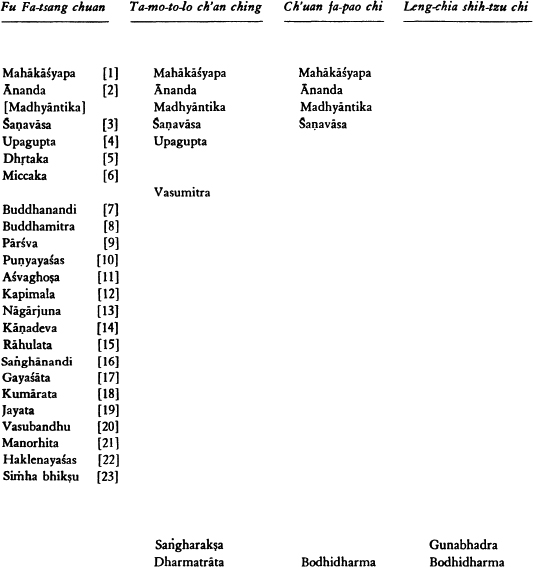

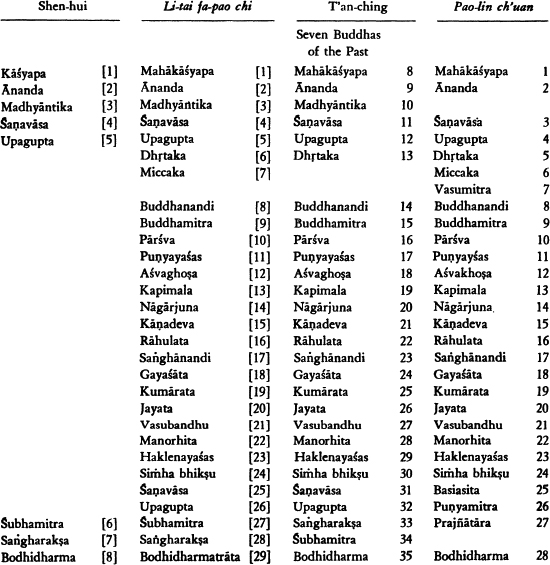

TABLE 1. THE TWENTY-EIGHT INDIAN PATRIARCHS*

*When the numerical designations for the Patriarchs do not appear in the original text, they are enclosed in brackets.

On the day that Bodhidharma died, Sung Yün13 of the Northern Wei, while on his way back to China, met Bodhidharma, who was returning to India, in the Pamirs. Upon being asked what was to happen to his school in the future, Bodhidharma replied that after forty years a native Chinese would appear to spread his teaching.14 When Sung Yün returned to China, he told Bodhidharma’s disciples of his interview. When they opened the grave they found that the body was no longer there.15

The above account is a version of the Bodhidharma legend as it appeared around the year 710 in one school of Ch’an. Whether what is described here reflects the beliefs of all schools at the time cannot be ascertained, for there is no evidence remaining from which such information can be derived. There were numerous disciples of the Fifth Patriarch, each proclaiming his own brand of Ch’an, and it would seem likely that there were various legends in common circulation, which were used by the different Ch’an teachers of the time as best fitted their needs. The Ch’uan fa-pao chi drew largely upon the Hsü kao-seng chuan for its information, in most instances abbreviating the notice considerably. There are, however, several new elements, such as the tale of Hui-k’o’s self-mutilation, the account of the attempts that were made to poison Bodhidharma, and the description of his encounter with Sung Yün. The chief departure, however, is the implication of a patriarchal succession. Tao-hsüan, in his Hsü kao-seng chuan, gives notices of Bodhidharma, Hui-k’o, and the Fourth Patriarch, Tao-hsin, along with a large number of other Ch’an teachers, but he makes no mention of the transmission of the Ch’an teaching from Patriarch to Patriarch. Since Tao-hsüan, who died in 667, kept adding to his work, which had been completed in 645, it may be assumed either that the concept did not exist in his time, or that he was unaware of it. Therefore, unless Tao-hsüan deliberately ignored it, it is probable that the concept of a patriarchal succession developed in the late seventh century, and had become generally accepted in Ch’an circles by the first decade of the eighth century, when the Ch’uan fa-pao chi was compiled.

In its account of Hui-k’o, the Second Patriarch, the Ch’uan fa-pao chi again relies, to a certain extent, on the Hsü kao-seng chuan. We are told that his name was Seng-k’o, although he was sometimes called Hui-k’o, and that he was of the Chi family, and a native of Wu-lao.16 Originally a scholar of Confucianism and an authority on various secular works, he later turned to Buddhism and became a monk. Meeting Bodhidharma at the age of forty, he practiced the Way for six years, and to show the earnestness with which he sought the Indian’s teachings, he cut off his left arm, betraying no sign of emotion or pain. Hui-k’o received his Master’s sanction, and, after Bodhidharma had returned to the West, stayed at the Shao-lin Temple at Sung-shan, where he carried on his teachings. During the T’ien-p’ing period (534–537) of the Northern Wei dynasty, he went to the capital at Yeh, where he continued his preaching with success, gained many converts, and led many persons to enlightenment. Here, as with Bodhidharma, many attempts were made to poison him, but they were all unsuccessful. He appointed Seng-ts’an as his successor, we are told, and transmitted to him the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra, predicting that after four generations the Sutra would change and become no more than an empty name.17

Although quite similar to the Hsü kao-seng chuan biography, and obviously derived in part from it, there are significant points of departure: the story of the cutting-off of his arm is again included; the account of Hui-k’o’s enemy, Tao-heng, who attempted to destroy him (so vividly described in the Hsü kao-seng chuan)18 is only briefly alluded to; and most significantly, where Tao-hsüan’s work records that Hui-k’o left no heirs, the Ch’uan fa-pao chi states specifically that he transmitted his teaching to Seng-ts’an, the Third Patriarch. This again indicates that, if there was a patriarchal tradition in Ch’an at this time, Tao-hsüan had no knowledge of it. Indeed, we have no evidence to show that such a tradition existed before the Ch’uan fa-pao chi.

The biography of Seng-ts’an19 is brief, and it is the first account we have of this extremely ambiguous figure in the ranks of the Ch’an patriarchate. The Hsü kao-seng chuan contains no separate biography; under the account of Fa-ch’ung,20 however, Seng-ts’an is listed as one of Hui-k’o’s disciples. The Ch’uan fa-pao chi, therefore, was unable to rely on the Hsü kao-seng chuan for its information, but there is no way of determining what source it used. Thus it may be presumed to be a distillation of the legends current at the time. We learn that the place of Seng-ts’an’s origin was unknown, and that as a youth he showed great promise, eventually becoming Hui-k’o’s disciple. During the Buddhist persecution of Emperor Wu of the Chou dynasty (574), he concealed himself at Huan-kung Mountain21 for ten years. We are told that before Seng-ts’an came here the mountain was filled with wild beasts, but that with his arrival they all vanished. Three priests who studied under him are mentioned by name. Then we hear that Seng-ts’an told his disciple Tao-hsin that he wished to return to the south, whereupon he handed down to him Bodhidharma’s teaching. After he left no one knew what had happened to him or where he had gone.

This simple story of a virtually unknown man is all the Ch’uan fa-pao chi has to tell us. Throughout the eighth century much material was added to his legend, his biography became more complex, and details were added to the story of his life, but Seng-ts’an always remains a relatively obscure figure in the history of Ch’an.

With the Fourth Patriarch, Tao-hsin, the account again becomes more concrete, largely because the Hsü kao-seng chuan provides fairly detailed information.22 In several passages the wording is identical with that in Tao-hsüan’s compilation and, although there is a degree of variation and considerable abbreviation, the Ch’uan fa-pao chi version is clearly derived from the former work.

We are told that Tao-hsin was a native of Ho-nei23 and that his patronym was Ssu-ma. Leaving home at the age of seven, he studied with an unidentified priest for six years. Sometime in the K’ai-huang era (581–601) he went to study under the Third Patriarch, remaining with him for eight or nine years. When the Third Patriarch left to go to Lo-fu24 Tao-hsin wanted to accompany him, but was told to remain behind, to spread the teaching, and only later to travel. During the disorders of the Ta-yeh era (605–617), just before the fall of the Sui dynasty, he went to Chi-chou,25 which for seventy days had been surrounded by a band of robbers and where the springs had all run dry. But when the Fourth Patriarch arrived, the waters again flowed, and his recitation of the Prajñāpāramitā Sutras caused the bandits to disperse. In 624 he went to Mount Shuang-feng where he stayed for thirty years. He is said to have advocated intensive sitting in meditation, and to have opposed the recitation of sutras as well as talking with other people. In the eighth month of 652 he ordered his disciples to make a mausoleum on the side of the mountain, and with this they knew that he was soon to die. He then transmitted his teachings to Hung-jen. When informed that his mausoleum had been completed, he passed away, to the accompaniment of strange natural phenomena: the ground trembled and the earth was enveloped in mists. At the time of his death he was seventy-two years old. The story goes on to state that three years after he died the doors to his stone mausoleum opened of themselves, and his body was revealed, retaining still the natural dignity it had possessed while he was alive. Thereupon his disciples wrapped the body in lacquered cloth and did not dare to shut the doors again.

The account of the career of the Fifth Patriarch, Hung-jen, is exceedingly brief. We are told that he was a native of Huang-mei, of the Chou family, and that he left home at the age of thirteen. Tao-hsin soon recognized his capacities: Hung-jen spent the whole night sitting in meditation and, without reading the sutras, attained enlightenment. He died in 67526 at the age of seventy-four, after having transmitted his teachings to Fa-ju.

The above summarizes what the Ch’uan fa-pao chi has to say about the first five Patriarchs of Ch’an. Its information is drawn largely from the Hsü kao-seng chuan, with a few legendary details from unknown sources added. For the Third and Fifth Patriarchs, of whom no account is given in Tao-hsüan’s work, it has little to say. This then is the status of the knowledge of the Patriarchs held by one school of Ch’an in the first decade of the eighth century. It is obvious that at this time the legends concerning them had yet to be highly elaborated; the Hsü kao-seng chuan was the basic source for the compiler of the Ch’uan fa-pao chi. Other schools undoubtedly knew further details and possessed other legends, but we have no contemporary records of them. Later works give more precise accounts, but we have no way of telling to what degree they represent newly invented material, the first recording of older legends, or the transmission of historical fact. As we watch the history and legend of Ch’an grow in its elaborateness with the passage of time, it would seem logical to assume that the absence of historical detail and biographical fact in the early works indicates that much of the later material is either the product of the imagination of later writers or the recapitulation and embroidering of earlier unrecorded legends.

The successor to Hung-jen was Fa-ju,27 the Ch’uan fa-pao chi informs us. Although his name soon disappears from the records of Ch’an history, and he is mentioned only as one of the disciples of the Fifth Patriarch in eighth-century works, he was evidently a personage of no little prominence towards the end of the seventh century. His name is found in the biographical notices of two of the famous Ch’an priests28 in the capital cities, and the inscription relating the history of the Shao-lin Temple refers to him.29 Fa-ju, we are told, was a native of Shang-tang30 and was surnamed Wang. He left home at nineteen, studied the canonical works in detail, and then traveled widely in search of the Way. Hearing of the genius of Hung-jen, he went to Mount Shuang-feng. Here his talents were recognized and the teaching was transmitted to him. Later he went to the Shao-lin Temple where he resided for several years. In the seventh month of 689 he called his disciples together and instructed them quickly to ask questions of him, so that they might be able to resolve their doubts. Then he seated himself in meditation beneath a tree and passed away. He was fifty-two years of age at death, and his heir was Shen-hsiu of the Yü-ch’üan Temple.31

Shen-hsiu (606?–706), whom the Ch’uan fa-pao chi lists as the heir of Fa-ju, was one of the great leaders of Ch’an in the early years of the century. Later we will see his name slandered and his teachings damned, but at the turn of the century he was a priest of great fame, honored by court and populace alike. In all other works he is known as the heir of the Fifth Patriarch; the Ch’uan fa-pao chi alone makes him a disciple of Fa-ju. There is no adequate explanation for this attribution; it must be left as one of the many puzzles and unsolved problems which so clutter the history of Ch’an of this period. One might hazard a guess that he was a priest of considerable prestige at the Shao-lin Temple near to the capital, who perhaps had a school of his own but died before he had produced any disciples of note.

Shen-hsiu,32 the Ch’uan fa-pao chi tells us, was a native of Ta-liang33 and a member of the Li family. Extremely bright as a child, he disliked the normal games of youth, and at thirteen, after witnessing the disasters and famine brought about by the disturbances of the time, he chanced to meet a good teacher, and decided to become a monk. He wandered about to various Buddhist establishments, and at twenty received the precepts. When he was forty-six he went to Hung-jen at the East Mountain, and the Master, at a glance, discerned his talents. Here he gained enlightenment after several years of study. He went then to Ching-chou,34 where he stayed for some ten years, yet all the time he was there the general populace was unaware of his accomplishments. In the I-feng era (676–678) he came to the Yü-ch’üan Temple, where again for ten years he did not transmit the doctrine. After Fa-ju’s death (689) students flocked to him from great distances and he was instrumental in leading many people to salvation. In the year 701 or 70235 he was invited to court by the Empress Wu, and was greeted with great splendor and ceremony, receiving the adulation of both monks and laymen. He died in Loyang at the T’ien-kung Temple on the twenty-eighth day of the second month of Shen-lung 2 (= April 15, 706); at the time he was over a hundred years of age. His body was interred in a pagoda at the Yü-ch’üan Temple, and he was given the posthumous title “Ta-t’ung ch’an-shih.”

The account of Shen-hsiu’s career, summarized above, is substantially the same as in other contemporary records, and with it the Chu’an fa-pao chi concludes its story of the Chinese Patriarchs. The last two biographies it provides are extremely factual and devoid of legendary elements, and probably represent a fairly accurate account of the careers of these two men.

This is what one school of Ch’an, which flourished in the first decade of the eighth century, knew about its ancestors. The next Ch’an historical work which has been preserved stems from the same or a closely related line, and similarly was recovered from among the documents discovered at Tun-huang. Known as the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi,36 it details the lineage of the school of Shen-hsiu and his disciples. Before discussing this new work, let us turn to a passage in a book that it quotes, the Leng-chia jen-fa chih. This work, now lost, was compiled by Hsüan-tse, a disciple of Hung-jen, the Fifth Patriarch, probably shortly after Shen-hsiu’s death in 706. As quoted by the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi,37 it gives the names of ten principal disciples of the Fifth Patriarch: Shen-hsiu, Chih-hsien, the assistant magistrate Liu, Hui-tsang, Hsüan-yüeh, Lao-an, Fa-ju, Hui-neng, Chih-te, and I-fang. Hsüan-tse, as compiler, does not add his name to the list of the ten chief disciples, but he may legitimately be included as the eleventh. These eleven men, it may be presumed,38 were the most active exponents of the Ch’an of Hung-jen. Some were of considerable eminence; others are known by name alone. Some founded schools and left disciples; others survive only in casual reference in other works. They do, however, indicate the great ferment and activity within Ch’an at this time.

Shen-hsiu, the great leader of the Laṅkāvatāra school, which came later to be known as Northern Ch’an, has an unquestionable place as one of the most eminent priests of his time. He is the only one of the eleven priests to whom a biographical notice in the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi is devoted; however, other sources reveal something of several of the other men included in the list.

Chih-hsien, of whom we shall have occasion to speak later,39 was the founder of a school in Szechuan, which attained a fair degree of renown. On the assistant magistrate Liu and on Hui-tsang we have no information whatsoever. Hsüan-yüeh is also virtually unknown, although one source states that he was summoned to court by the Empress Wu.40

Lao-an was a priest of unusual renown, partly because of the extraordinary age he is said to have attained. Most works give his name as Hui-an,41 which was his real Buddhist name. Of the Wei family, he was born in 582 in Chih-chiang in Ching-chou.42 Wandering from temple to temple, he gave his efforts to helping the starving. Sometime in the Chen-kuan era (627–649) he went to Mount Shuang-feng, where he studied under Hung-jen. After completing his training, he resided in a number of temples; in 664 he was at Mount Chung-nan in Shensi and, although summoned by Emperor Kao-tsung, declined to come to court. At different times he was at the Hui-shan Temple in Loyang, the Yü-ch’üan Temple, and the Shao-lin Temple. He was called to court by the Empress Wu, and is said to have been honored on a par with Shen-hsiu. He died in 709. His heir, Yüan-kuei (644–716), and the latter’s disciple Ling-yün (d. 729) were both priests of sufficient consequence to have biographical monuments inscribed in their honor.43

Fa-ju, seventh on the list of disciples, we have seen before in the Ch’uan fa-pao chi. Hui-neng, the Sixth Patriarch, destined to become, with Bodhidharma, the most famous of the Ch’an Masters, is mentioned here for the first time in this or any other text44 To him is ascribed the Platform Sutra, and his history and teachings appear constantly in the literature of the latter part of the eighth century. He is a younger contemporary of Shen-hsiu, a fellow disciple under Hung-jen, but it is only later that he comes to be known. The biography of Hui-neng typifies the problems of Ch’an historiography: the later the work, the more detailed is the information provided. The works which concern him cannot be dated with any certainty, nor can we be sure that they do not represent information which has been revised by later hands. We need not doubt the accuracy of the information about men who had temporary renown, and whose fame receded into historical obscurity, men such as Shen-hsiu and most of the other disciples of Hung-jen. They did not become absorbed into the legend, although in some ways they helped to promote a part of it, as they strove to strengthen the position of their own Ch’an schools. But, as we shall see later, there is no way of distinguishing fact from legend in the case of Hui-neng. All one can do is to point out what might have happened and what probably did not happen, and suspend judgment until more evidence becomes available—if ever it does.

Chih-te and I-fang, ninth and tenth on the list, are unknown. Of Hsüan-tse, the compiler of the lost Leng-chia jen-fa chih, we also know virtually nothing. He is said to have been called to the imperial court;45 thus he was most likely a man of no little importance. His disciple, Ching-chüeh, of whom also little is known, was the compiler of the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi, and was evidently a man of some consequence, since no less a person than Wang Wei wrote his pagoda inscription.46 He was born, most likely, in 683 and died some time in the period between 742 and 753.47

Of the eleven heirs of Hung-jen, then, we have three men of prime importance, men who founded major schools of Ch’an, or to whom the foundation is attributed: Shen-hsiu, Chih-hsien, and Hui-neng. We have four men, Hsüan-yüeh, Lao-an, Fa-ju, and Hsüan-tse, of whom we have slight, and at times negligible information, but who may well have been fairly important Ch’an Masters in the early eighth century. And we have four men of whom nothing whatsoever is known.

The Leng-chia shih-tzu chi, which contains this information concerning Hung-jen’s disciples, is, chronologically, the second text still extant that deals with the history of Ch’an. An exact dating of the work cannot be made, but it may be placed somewhere in the K’ai-yüan era (712–741)48 and, as we have seen, it contains material which can be dated to the first decade of the eighth century. At least five different copies or fragments have been found among the Tun-huang documents, which would indicate that the work had a fairly wide circulation.

The Leng-chia shih-tzu chi makes several contributions to the advancement of the Ch’an legend, and also adds new material, which later Ch’an writers were to reject as untrue. It is the first work to give numerical designations to the Patriarchs, listing eight: (1) Gunabhadra, (2) Bodhidharma, (3) Hui-k’o, (4) Seng-ts’an, (5) Tao-hsin, (6) Hung-jen, (7) Shen-hsiu, and (8) P’u-chi49 No mention is made of the early Indian Patriarchs. By placing Gunabhadra (394–468) as the First Patriarch, the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi seems to be attempting to establish a new legend, although it may possibly be perpetuating an older one of unknown origin. The selection of Gunabhadra as the First Patriarch of the sect is based on an obvious reason: he was the translator of the four-chüan version of the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra, the scripture on which this school founded its teachings. Furthermore, the Hsü kao-seng chuan mentions that Bodhidharma transmitted this sutra in four chüan to Hui-k’o.50 The introduction here of this novel theory of the descent of the Chinese Patriarchs is indicative of the newness of the patriarchal tradition within Ch’an. The legend which was eventually to gain acceptance had yet to be devised, the connection with India had yet to be established, and there was still room for invention. Later, in a work dating around 780, we find the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi severely taken to task for its assertion that Gunabhadra was Bodhidharma’s teacher.51

The notice in the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi tells us very little of Gunabhadra.52 He was a priest from central India, a follower of the Mahāyāna teaching, who arrived in Canton by ship during the Yüan-chia53 era (425–453) of the Sung dynasty. Welcomed by the emperor, he soon undertook the translation of the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra. The remainder of this rather lengthy notice is devoted to quotations attributed to Gunabhadra, as well as others drawn from various canonical works. Gunabhadra is associated with the Pao-lin Temple, where Hui-neng made his home, and later texts attribute to him a prediction in which he foretells the arrival of the Sixth Patriarch.54 Gunabhadra translated a great number of works, but there is nothing to indicate that he gave particular emphasis to the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra. Futhermore, there is no evidence to show that he ever met Bodhidharma.55 The whole story is obviously fictional, either devised by the compiler of this work or borrowed by him from elsewhere. That it was not perpetuated is evidence of its absurdity for, throughout the creation of the legend of the patriarchal transmission, Ch’an has tended to reject any attributions that were completely untenable, and that might leave it open to attack by other schools of Buddhism. This will be seen later in the rejection of an equally indefensible theory of thirteen Patriarchs from Buddha through Hui-neng, and the elimination of certain obvious errors in the lineage as it developed through the course of the eighth century.

Bodhidharma is listed as the Second Patriarch, and the text specifically states that he received the teaching from Gunabhadra. Included is the text of Bodhidharma’s doctrine of the “Two Entrances and the Four Categories of Conduct,” which is described as having been compiled by Bodhidharma’s disciple, T’an-lin.56 We are also informed that Bodhidharma made a commentary on the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra, the Leng-chia yao-i, otherwise known as Ta-mo lun.57 There is no significant enlargement of the legend of Bodhidharma here, and this is true also of the biographies of the other Patriarchs; they consist primarily of brief notices of the career and a series of quotations, drawn largely from a variety of sutras, which are attributed to each Patriarch.

The Leng-chia shih-tzu chi makes no further mention of Fa-ju, whose cause had been championed by the Ch’uan fa-pao chi, and it carries the line of transmission one generation further, by adding P’u-chi as eighth in the line of succession. Along with P’u-chi are listed three other heirs of Shen-hsiu: Ching-hsien, I-fu, and Hui-fu. Almost no information is provided here for any of these men; they were, however, significant figures in the Ch’an of the capital cities. P’u-chi and his disciple I-fu both had access to the imperial court, were accorded exceptional patronage, and were honored as national teachers. Their biographies are known from contemporary records.

P’u-chi,58 a native of Ho-tung,59 left home at an early age, and went to study under Shen-hsiu at the Yü-ch’üan Temple. He did not officially become a monk until his Master was called to court by the Empress Wu. In 735 he was summoned by the emperor and gained immense popularity, not only in court circles, but among the general populace as well. When he died in 739 a grand funeral service was held, attended by numerous high officials, and by so many of the general public that the villages were said to have been emptied of people.

I-fu,60 from T’ung-ti,61 studied Taoism and the Book of Changes as a youth and then, turning to Buddhism, concentrated on the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka, Vimalakīrti, and other Mahāyāna sutras. He went to the Shao-lin Temple, intending to study under Fa-ju, but when he arrived he found that this priest had already passed away. Thus he became a disciple of Shen-hsiu and studied under him until the latter was called to court. After Shen-hsiu’s death he served at various temples in Ch’ang-an, and was active in propagating the teachings among both the high officials and the common people. When he died in 736, the emperor sent a messenger to convey his condolences.

Of the two other heirs of Shen-hsiu mentioned in the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi, Hui-fu is completely unknown, but Ching-hsien,62 although forgotten in later biographies, seems to have been a man of considerable importance. A native of Fen-yin,63 he came to Shen-hsiu shortly before the latter’s death in 706. He was called to court by the Emperor Chung-tsung, who had heard of his great popular appeal, but soon left the palace precincts, finding the monastic environment more to his liking. He died in 723 at the age of sixty-four.

We have examined in considerable detail the careers of the men prominent in the Ch’an movement in the first three decades of the eighth century. These men were all associated with the Ch’an of Shen-hsiu or related schools. They are described in the histories of their own sect, and many of those of whom brief mention alone is made were important enough personages to have had inscriptions in their honor composed on their deaths. There may well have been other schools of Ch’an extant at the time, but of them we have no record. The Ch’an of Shen-hsiu and his disciples had gained a great following, both within the imperial court and among the people at large, especially in the capital cities. With this popularity went prestige, much power, and resplendent temples. With it also went recognition as the orthodox Ch’an teaching of the time, and also recognition of the lineage of the sect.

Yet neither the tradition adopted by the Ch’uan fa-pao chi nor that of the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi was accepted as the final version of Shen-hsiu’s school. In Chang Yüeh’s inscription for Shen-hsiu the lineage is given as: (1) Bodhidharma, (2) Hui-k’o, (3) Seng-ts’an, (4) Tao-hsin, (5) Hung-jen, and (6) Shen-hsiu.64 Three other contemporary inscriptions attest to the same lineage, and they extend the line by one generation, by including P’u-chi as the Seventh Patriarch.65 This, then, became the orthodox line of transmission in the school of Ch’an founded by Shen-hsiu.

While the Ch’an of Loyang and Ch’ang-an was enjoying this immense popularity and power, a then unknown priest in Nan-yang,66 Shen-hui by name, was intent upon building a new school of his own. To this end he launched an attack upon the Ch’an of Shen-hsiu’s descendants and, after many years of struggle, eventually carried the day. The story of this new kind of Ch’an was unearthed by the late Dr. Hu Shih, who found among the Tun-huang documents housed at the Bibliothèque Nationale several manuscripts containing the sayings and writings of Shen-hui and his followers. These he collated and published, and through his studies rewrote the history of Ch’an during the T’ang dynasty. The career of Shen-hui fascinated this multifaceted scholar, who, toward the close of his diversified life, returned to the study of this champion of what came to be known as “Southern Ch’an.” Since Hu Shih’s studies caught the imagination of both Western and Oriental scholars, a considerable body of material concerning Shen-hui has been produced.67

To understand the revolution in Ch’an Buddhism brought about by Shen-hui, it is necessary to examine his career in some detail.68 His surname was Kao, and he was a native of Hsiang-yang in Hupeh. As a child he took easily to study, and soon mastered the intricacies and the obscurities of the classics. He found much to his satisfaction in the Lao Tzu and the Chuang Tzu, but when he read the History of the Later Han Dynasty he became aware of Buddhist doctrines and, shunning an official career, turned to their study. After entering a temple near his home, he went, when he was about forty years of age,69 to Ts’ao-ch’i,70 where he studied under Hui-neng. Here he stayed for a few years, perhaps from around 708 until Hui-neng’s death in 713.71 After this he traveled about, and in 720 was ordered by imperial command to reside at the Lung-hsing Temple in Nan-yang. From this time until 732 our information is scanty. It may be presumed that he studied and preached, spreading his own teachings, and gained both in popularity and in the number of converts made. Then, on the fifteenth day of the first month of 732 (= February 15, 732)72 he organized a great conference at the Ta-yün Temple in Hua-t’ai,73 at which he mounted a grand attack on the Ch’an of P’u-chi, the successor to Shen-hsiu. Details of this and subsequent condemnations of his rivals are recorded in the P’u-t’i-ta-mo Nan-tsung ting shih-fei lun, compiled by Tu-ku P’ei.74 At this time, as well as on later occasions, he pressed his assault on the established school of Ch’an.

He made many charges and many pronouncements. Among other things, he told the history of his sect. According to Shen-hui, Bodhidharma, the third son of an Indian king, arrived in Liang and held discourse with the Emperor Wu.75 To the emperor’s question as to whether he, the emperor, had gained merit by building temples, helping people, making statues, and copying sutras, Bodhidharma replied: “No merit.” The emperor did not understand and Bodhidharma left for Wei, where he met Hui-k’o. The latter sought desperately to become his disciple, and Bodhidharma finally relented when Hui-k’o, to show his earnestness, seized a sword and cut off his left arm. Bodhidharma later handed his robe to Hui-k’o as a symbol of the transmission of the Dharma. Hui-k’o then handed it to Seng-ts’an, Seng-ts’an to Tao-hsin, Tao-hsin to Hung-jen, and Hung-jen transmitted it to Hui-neng. For six generations, we are told, the robe was handed down from Patriarch to Patriarch.76

Shen-hui is making two points here: he is establishing Bodhidharma’s robe as a symbol of the transmission of the Dharma, and he is refuting the accepted line of the transmission, by substituting Huineng for Shen-hsiu. Up to now we have heard nothing of Hui-neng, except for the brief mention of him as one of the heirs of the Fifth Patriarch in the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi; his name does not appear in sources other than those of dubious reliability.77 Furthermore, Shen-hui, by introducing the stories of Bodhidharma and the Emperor Wu and of Hui-k’o’s severed arm, is deliberately embroidering the legendary aspects of the early patriarchs. These stories are repeated ad nauseum in later Ch’an works and have proven to be the most popular and enduring of Ch’an legends. Hu Shih has suggested that they were made up by Shen-hui,78 but it appears more likely that they were common stories, current at the time,79 and that Shen-hui merely borrowed them for the effect they might have. Certainly, his use of them served to perpetuate them in the developing Ch’an legend.

Elsewhere, Shen-hui went on to say: “During his lifetime the Ch’an Master Shen-hsiu stated that the robe symbolic of the Dharma, as transferred in the sixth generation, was at Shao-chou;80 he never called himself the Sixth Patriarch. But now P’u-chi calls himself by the title of the Seventh Patriarch and falsely states that his Master was the Sixth. This must not be permitted.”81

In the same vein, we read: “The Dharma-master Yüan asked: ‘Why should P’u-chi not be allowed to do this?’ The priest [Shen-hui] answered: ‘Although the Ch’an Master P’u-chi speaks of the Southern School, he is only plotting to destroy it.’ “Shen-hui then goes on to charge that in the third month of 714 P’u-chi sent a certain Chang Hsing-ch’ang,82 disguised as a priest, to take the head from Hui-neng’s mummified body, and that he inflicted three knife wounds upon it. Furthermore, Shen-hui claims, P’u-chi sent his disciple Wu P’ing-i83 to efface the inscription on the Master’s stele and to substitute another one that said that Shen-hsiu was the Sixth Patriarch. P’u-chi, Shen-hui continues, erected a stone inscription at Sung-shan,84 constructed a building known as the “Hall of the Seventh Patriarch,” and compiled the [Ch’uan] fa-pao chi,85 in which he failed to make mention of Hui-neng’s name. Shen-hui continued his attack, stating that Fa-ju was I fellow student with Shen-hsiu and was also not in the line of transmission, yet in the Ch’uan fa-pao chi he is called the Sixth Patriarch. Shen-hui concludes sarcastically: “Now P’u-chi erects a stele for Shen-hsiu in which he calls him the Sixth Patriarch, and then he compiles the Ch’uan fa-pao chi, in which he makes Fa-ju the Sixth Patriarch. I don’t understand how these two worthies can both be the Sixth Patriarch. Which is right and which is wrong? Let’s ask the Ch’an Master P’u-chi to explain it himself in detail.”86

In the passage summarized above, Shen-hui makes particular mention of P’u-chi’s attempts to destroy the Southern School (Nan-tsung). There seems to have been considerable confusion at this time concerning the use of this term.87 In the preface to a commentary on the Heart Sutra by Ching-chüeh,88 mention is made of the Southern School in reference to the teachings which Gunabhadra handed down to Bodhidharma. Thus, what came to be known as the Northern School of Ch’an, that of Shen-hsiu and P’u-chi, was at one time known as the Southern School. That this caused Shen-hui considerable consternation is evident from another passage in the P’u-t’i-ta-mo Nan-tsung ting shth-fei lun: “When the priest [Shen]-hsiu was alive, all students referred to these two great Masters, saying, ‘In the South, [Hui]-neng; in the North, [Shen]-hsiu,’ . . . therefore we have the two schools, the Southern and the Northern. . . [P’u-chi] now recklessly calls his [teaching] the Southern Sect. This is not to be permitted.”89

Furthermore, the story of the attempt to cut off the head from Hui-neng’s mummified body, which figures so prominently in some of the later works,90 appears here for the first time. Similarly, the story of the effacement of Hui-neng’s inscription and the substitution of an alternate version appears also in a subsequent biography.91 There is no way of determining whether these stories were inventions of Shen-hui or were merely tales current at the time.

In another work Shen-hui discusses the lineage of Ch’an: “Bodhidharma received the teaching from Saṅgharakṣa, Saṅgharakṣa received it from Śubhamitra, Śubhamitra received it from Upagupta, Upagupta received it from Śaṇavāsa, Śaṇavāsa received it from Madhyāntika, Madhyāntika from Ānanda, Ānanda from Kāśyapa, Kāśyapa from the Tathāgata. When we come to China, Bodhidharma is considered the Eighth Patriarch. In India Prajñāmitra92 received the Law from Bodhidharma. In China it was Hui-k’o ch’an-shih who came after Bodhidharma. Since the time of the Tathāgata there were, in all, in India and China, some thirteen Patriarchs.”93

This extraordinary version of the patriarchal lineage involves a host of problems. It is drawn directly from the body of the Ta-mo-to-lo ch’an-ching, not from the preface as Shen-hui himself states.94 The latter work does not pretend to give a definitive list of all the Patriarchs, but Shen-hui seems to have regarded it as such. The absurdity of having only thirteen Patriarchs from the time of the Buddha to the eighth century seems not to have occurred to Shen-hui; however, we see no later adoption of this example of his inventiveness in other works95 The theory has been advanced that Shen-hui accepted the lineage of twenty-eight Patriarchs, which was afterwards to become the official one, but this seems quite doubtful.96

In his list of thirteen Patriarchs, Shen-hui made one serious mistake. He inverted the first two characters of the name of the sixth Indian Patriarch, Vasumitra, as given in the Ta-mo-to-lo ch’an-ching, arriving at the name Śubhamitra. This error was later perpetuated in the Tun-huang edition of the Platform Sutra (sec. 51), as well as in the Li-tai fa-pao chi.97 In addition, Shen-hui arbitrarily changed the name of Dharmatrāta to Bodhidharma; the Ta-mo-to-lo ch’an-ching, of course, makes no mention of Bodhidharma.

Shen-hui made a considerable number of statements about Hui-neng. We do not know the source of his information and there is no corroborating evidence of sufficient reliability to enable us to determine whether he was inventing stories or merely passing along legendary material current at the time. Shen-hui, in his efforts to justify his claim that Hui-neng was legitimately the Sixth Patriarch, tells the story that when the Empress Wu invited Shen-hsiu to court, in the year 700 or 701, this learned priest is alleged to have said that in Shao-chou there was a great master [Hui-neng], who had in secret inherited the Dharma of the Fifth Patriarch.98 This story appears in one or another form in almost every biography of Hui-neng, its most common form being an imperial proclamation requesting Hui-neng, on Shen-hsiu’s recommendation, to appear at court. It is included in the Ch’üan Tang wen,99 the monumental collection of T’ang documents. Writers who emphasize the importance of Hui-neng, and seek to establish the historicity of his biography, constantly refer to it, but it would seem to be highly suspect, and scarcely serviceable as early evidence of Hui-neng’s activity. The Ch’üan T’ang wen was compiled in 1814, using indiscriminately all available sources, many of them of a very late date, so that an unbounded faith in the validity of all the material it contains seems hardly justified. The alleged recommendation made to the Empress Wu by Shen-hsiu is, depending upon the source, ascribed also to Emperor Chung-tsung,100 and even to Emperor Kao-tsung.101 This hardly contributes to a feeling of confidence in its reliability. It would appear rather incautious to afford it the historical respectability which many writers have accorded it.102

Shen-hui, in addition to accusing P’u-chi of sending representatives to cut off the head of Hui-neng’s mummified body and to efface his inscription, gave a biographical sketch of Hui-neng, along with those of the five other Patriarchs.103 The information given is substantially the same as the autobiographical sections and the description of Hui-neng’s death found in the Platform Sutra, although in a much more concise form.104 The authenticity of the Platform Sutra will be discussed later,105 but it must be pointed out here that, despite his championing the cause of his teacher, Shen-hui never quotes from the writings or sayings of Hui-neng. If such had existed, it would seem logical that he would have used them as his authority. As will be seen, there are a number of instances in which the texts of Shen-hui’s works and the Platform Sutra are identical, and there can be no question that the Tun-huang version of the latter work is chronologically later than the surviving works of Shen-hui. These and other factors have prompted Hu Shih to assert that the Platform Sutra was “composed by an eighth-century monk, most likely a follower of Shen-hui’s school, who had read the latter’s Discourses and decided to produce a Book of the Sixth Patriarch, by rewriting his life-story in the form of a fictionalized autobiography and by taking a few basic ideas from Shen-hui and padding them into [the] Sermon of Hui-neng.”106 The alternative view is that there existed an early version of Hui-neng’s sayings which has not survived, from which Shen-hui derived his ideas. This view, adopted by many, cannot be altogether rejected for reasons which will be discussed later, but it certainly seems probable that Shen-hui either perpetuated, organized, or perhaps deliberately fabricated much of the legend of Hui-neng.

Shen-hui did not attack P’u-chi and Northern Ch’an only on the basis of the alleged usurpation of the position of the Sixth Patriarch. He accused them of holding erroneous views as well. His comments on the meditation practice of the Northern school are reflected in the following passage:

The Master Yüan said: “P’u-chi ch’an-shih of Sung-yüeh and Hsiang-mo107 of Tung-shan, these two priests of great virtue, teach men to ‘concentrate the mind to enter dhyāna, to settle the mind to see purity, to stimulate the mind to illuminate the external, to control the mind to demonstrate the internal.’ On this they base their teaching. Why, when you talk about Ch’an, don’t you teach men these things? What is sitting in meditation (tso-ch’an)?’

The priest [Shen-hui] said: “If I taught people to do these things, it would be a hindrance to attaining enlightenment. The sitting (tso) I’m talking about means not to give rise to thoughts. The meditation (ch’an) I’m talking about is to see the original nature.”108

On the identity of prajñā and dhyāna, Shen-hui states, in a passage closely paralleling one in the Platform Sutra (sec. 13):

The Dharma-master Tieh asked: “What does the statement, ‘meditation (dhyāna) and wisdom (prajñā) are alike’ mean?”

[Shen-hui] answered: “Not to give rise to thoughts, emptiness without being, this is the true meditation. The ability to see the non-rising of thoughts, to see emptiness without being, this is the true wisdom (prajñā). At the moment there is meditation, this is the substance of wisdom; at the moment there is wisdom, this is the function of meditation. Thus, the moment there is meditation, it is no different from wisdom. The moment there is wisdom, it is no different from meditation. Why? Because by their nature, of themselves, meditation and wisdom are alike.”109

Statements such as those above have prompted Hu Shih and others to conclude that Shen-hui swept aside all meditation, rejected sitting practices, and produced a “new Ch’an which renounces ch’an itself and is therefore no ch’an at all.”110 This view, however, seems somewhat extreme. Shen-hui was attacking a particular type of meditation practice, which he attributed to Northern Ch’an. It would seem that what Shen-hui is saying is that meditation need not be limited to a formalized method of sitting alone; it can be practiced at any time. This is certainly the concept held by the new schools of Ch’an which rose at the end of the eighth century.111 Shen-hui states that once there is true meditation then there is wisdom; wisdom is not a thing to be aimed at by “settling the mind to see purity.” It is the method, not the meditation, that he is attacking. If we assume that Shen-hui discarded meditation and rejected Ch’an completely, then we must conclude that his ideas were totally ignored by later Ch’an teachers, for certainly meditation was practiced by the later schools. No matter how varied the practices, Ch’an has always been within the framework of Buddhism as a whole.

That Shen-hui was not beyond fabrication is indicated by his assertion that all the Patriarchs, from Bodhidharma through Hui-neng, advocated the efficacy of the Diamond Sutra, and that it was this work, rather than the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra which was handed down in the school.112 The Hsü kao-seng chuan, the Ch’uan fa-pao chi, and the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi all refute this claim. Frequent quotations from the Diamond Sutra and lengthy discussions devoted to it113 emphasize its importance in Shen-hui’s teachings, but to claim that it was taught by Bodhidharma and all later Patriarchs is pure fabrication.

The most frequent charge made against the Northern School was that it taught a gradual method of attaining enlightenment, as opposed to the sudden method advocated by the Southern School. Shen-hui’s advocacy of the sudden method is advanced in his works,114 but it is most strongly emphasized throughout the Platform Sutra. This attack was clever and effective; it may, however, have been quite unjustified, for there is evidence to show that Shen-hsiu also advocated the sudden method, while insisting on the initial mastery of meditation techniques for those just “entering upon the Way.”115 We know few details of the teachings of Northern Chan, for most of its works have not been preserved.116 Indications are, however, that the school did not merely practice the gradual method of introspection that Shen-hui described, nor did it confine itself solely to the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra. It seems to have advocated a far more sophisticated teaching, reflecting Hua-yen concepts and Prajñāpāramitā thought,117 and may well have been much closer to the teaching of the Fifth Patriarch than was the Ch’an which Shen-hui advocated.

There is little evidence to account for Shen-hui’s activities between the years 732 and 745. He seems to have continued preaching, making many converts, and to have associated frequently with officials of high rank, traveling rather widely in the course of his work. This was a particularly trying time in the political history of the T’ang dynasty.118 Emperor Hsüan-tsung, who had begun his forty-four-year reign in 712, was at the outset an astute and competent ruler. His efforts were directed towards the expansion of empire as well as the concentration of power in the hands of the central government. Great military victories brought numerous outlying areas under Chinese control; internally a variety of fiscal, economic, and political reforms was initiated. Buddhism, which had enjoyed great patronage and indulgence during the reigns of the Empress Wu and her two successors (690–712), found the imperial munificence drastically curtailed. Restrictions were imposed on the size of temple estates and the building of temples, and more stringent requirements were established for those who would become monks and nuns. Although Hsüan-tsung gave certain priorities to Taoism, the Buddhists were not greatly deprived. In fact, it may well have been that these new economic restrictions helped to further the intellectual development of the religion, for some of the greatest figures in Chinese Buddhism flourished during this period. As Hsüan-tsung’s reign continued, the inevitable intrigues between rival political factions striving for power arose, seriously eroding the programs advocated by the emperor. Hsüan-tsung himself, during the latter half of his reign, seems to have lost interest, and to have dissociated himself from the intrigues surrounding him. We do not have much information concerning Buddhism’s involvement with the plots and counterplots that beset the empire, but we do know that many of the great ministers and military leaders were present at public sermons and attended Buddhist services and ceremonies. Certainly, the fact that certain priests gained fame while others remained in obscurity may well have depended on the astuteness with which they selected their political associations.

In 745 Shen-hui was invited by the vice-president of the army ministry, Sung Ting,119 to come to Loyang, and to take up residence at the Ho-tse Temple. Here he held forth on the doctrines of the Southern School of Hui-neng, continuing his attack on the followers of P’u-chi’s school. P’u-chi himself had died in 739. Shen-hui, after eight years of brilliant success as a preacher, fell afoul of the censor Lu I,120 who was prejudiced in favor of Northern Ch’an,121 and who reported that Shen-hui was plotting moves inimical to the government. Shen-hui was called to Ch’ang-an, where he was interviewed by Emperor Hsüan-tsung, and eventually sent into exile. During his banishment the nation was shaken to its roots by the rebellion of An Lu-shan, a general of Sogdian and Turkish ancestry. The rebel armies swept down upon the capital cities, capturing both Loyang and Ch’ang-an, and drove the imperial court into exile in 756. The emperor fled, leaving the affairs of state in the hands of the heir-apparent, who rallied the government forces and eventually succeeded in suppressing the rebellion. The T’ang dynasty survived for over a century and a half after this revolt, but it was never to regain even a measure of the glory of the early years of Hsüan-tsung’s reign.

While the government forces were striving to subdue the revolt, they found themselves in extreme financial difficulties. To raise money to support the armies, ordination platforms were set up in each prefecture for the investiture of monks and the selling of certificates. Shen-hui was called back from exile to assist in this money-raising campaign, and he directed the ordinations in Loyang with such spectacular success that he contributed substantially to the beleaguered government. Although Loyang was in ruins, the director of palace construction was ordered to erect a Ch’an sanctuary for him within the grounds of the Ho-tse Temple. He remained active until his death, the date of which is variously given: the Yüan-chüeh chin g ta-shu ch’ao has 758,122 the Sung hao-seng chuan, 760.123 Hu Shih has recently established the correct date as 762.124

After a long and strenuous career Shen-hui succeeded in establishing his school of Ch’an as the dominant one in the capital cities. Our records are scanty for this period, but it should not be assumed that Northern Ch’an gave up without considerable struggle. Although ignored in the histories, there is evidence to show that P’u-chi’s school continued for several generations after his death in 739.125 Hung-cheng, of whom we know little, is described as being in the “eighth generation” of Ch’an.126 Another priest, more prominent in Japan than China, was Tao-hsüan (702–760), a disciple of P’u-chi, who arrived in Japan in 736. He taught Vinaya and Hua-yen philosophy, and was the teacher of Gyōhyō (722–797), who in turn was the instructor of the famous Saichō (767–822), who later went to China himself and brought back the T’ien-t’ai teachings to his country. Another Northern Ch’an priest of note was T’ung-kuang (700–770), whose name does not appear in the biographical works, but of whom we know through his inscription.127 He had a large number of followers, and was himself probably one of the “sixty-three of the myriad disciples of P’u-chi who entered the hall (became active Ch’an teachers).”128 Though precise information is lacking, it would seem that the Northern Ch’an school probably continued into the ninth century, without developing any priests of prominence, and most likely died out with the persecutions of the Hui-ch’ang era (842–845).

Shen-hui’s school may well have suffered a similar fate. Although we hear of several disciples,129 none achieved particular renown with the exception of Tsung-mi (780–841),130 his descendant in the fifth generation. Tsung-mi left no disciples of note, and as with Northern Ch’an, it may be presumed that the school died out with the persecutions of Hui-ch’ang.

While Shen-hui was raising Hui-neng to the recognized status of the Sixth Patriarch,131 either perpetuating an old legend or creating a new one, other Ch’an schools were busy building “histories” of their own lineage, as well as of Ch’an as a whole. The legend of the Ch’an Patriarchs continued to develop, and new versions began to appear. In the inscription by Li Hua for the T’ien-t’ai priest Tso-ch’i Hsüan-lang (673–754),132 probably written shortly after the latter’s death, mention is made of several schools of meditation, including those associated with the T’ien-t’ai sect. Four of these may be classified as belonging to Ch’an:

1. The school which started with the Buddha, who transmitted the mind-dharma to Kāśyapa, from whom it was handed down through twenty-nine Patriarchs until it reached Bodhidharma, who transmitted the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra, which passed through eight generations, reaching the Ch’an Master Hung-cheng. This was the Northern School of Ch’an.

2. The school which reached the Ch’an Master Ta-t’ung [Shen-hsiu] in the sixth generation from Bodhidharma, and was transmitted from him to the Ch’an Master Ta-chih [I-fu], who in turn transmitted it to the Ch’an Master Jung133 of the Shan-pei Temple in Ch’ang-an. This school is referred to as the “one fountain-head of Northern Ch’an.”

3. The school referred to as Southern Ch’an, which descended from Bodhidharma to the Fifth Patriarch Seng-ts’an,134 from whom it was transmitted to Hui-neng.

4. The school transmitted from Bodhidharma to Tao-hsin in the fourth generation, and from him to the Ch’an Master [Fa]-jung135 (594–657) of Mount Niu-t’ou, from whom it passed to the Ch’an Master Ching-shan.136

From this inscription it would seem evident that Li Hua considered the Northern School of Ch’an as the dominant one, although he recognizes the presence of the Southern School, without mentioning Shen-hui’s name. If the assumption that this inscription was made shortly after Hsüan-lang’s death is correct, then it may have been composed during the time Shen-hui was in exile, which might account for the failure to acknowledge him. The statement that there were twenty-nine Patriarchs from the Buddha to Bodhidharma is a new departure, seen here for the first time. They are not specifically itemized, so that no details of the names of the Patriarchs are determinable, but the inscription shows that in Northern Ch’an a theory of twenty-nine Indian Patriarchs had gained currency.137

This theory is continued in another Tun-huang document, the Lt-tai fa-pao chi,138 chronologically the next of the Ch’an histories. Again, the exact dating is uncertain, but it seems safe to place it at around the year 780.139 Representing an entirely different line of Ch’an than has been seen up to now, it shows the influence of both the Northern and the Southern schools in its account of the patriarchal succession. The name of each of the Patriarchs is given;140 for the first twenty-four the Yin-yüan fu fa-tsang chuan is the authority, for the next five Shen-hui is followed. There are slight variations in the list: Madhyāntika is given as the third Indian Patriarch, whereas the Yin-yüan fu fa-tsang chuan omits him as being of a collateral branch; however, substantially the list is the same. The Li-tai fa-pao chi, for the twenty-fifth through twenty-ninth Patriarchs, depends on the fourth through eighth Patriarchs in Shen-hui’s list of thirteen Patriarchs. Shen-hui had drawn these from the Ta-mo-to-lo ch’an-ching, but the present work, since it repeats his errors, was obviously based on Shen-hui. Here the fourth and fifth Patriarchs are repeated as the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth,141 and Shen-hui’s carelessness in reversing the first two characters in Vasumitra’s name, thus arriving at Śubhamitra,142 is perpetuated. Furthermore, where Shen-hui arbitrarily changed the name of Dharmatrāta to Bodhidharma, the Li-tai fa-pao chi has seen fit to combine the two names, coming up with Bodhidharmatrāta.

This work, then, in so far as the Indian Patriarchs are concerned, seems to have borrowed the tradition of Northern Ch’an, for it follows the number described in Li Hua’s inscription. Yet at the same time it was influenced by Shen-hui’s list of Patriarchs. Southern Ch’an may at this time also have had a theory of twenty-nine Patriarchs, for the version in the Platform Sutra (sec. 51) is based largely on the Li-tai fa-pao chi.143 There is obviously a close connection between parts of this work and the biographical sketches of the Chinese Patriarchs as given by Shen-hui. An alternate title for the Li-tai fa-pao chi is the Shih-tzu hsich-mo chuan. A work of the same title is mentioned, in Tu-ku Pei’s preface to the P’u-t’i ta-mo Nan-tsung ting shih-fei lun,144 as a book which gives the genealogy of Shen-hui’s school. Furthermore, the biographies here and in Suzuki’s text of the Shen-hui yü-lu145 are quite similar, and one is obviously derived from the other. Unfortunately there is no way of determining what the exact relationship between these various works is.

The Li-tai fa-pao chi begins by listing the twenty-nine Indian Patriarchs by name. Included is a sharp condemnation of the Leng-chia shih-tzu chi, which makes Gunabhadra the First Patriarch. The text points out that Gunabhadra was but one of several translators of the Laṅkāvatāra Sutra, none of whom were Ch’an Masters. Furthermore, we are told, the Laṅkāvatāra represents the transmission of a written teaching, whereas Bodhidharma did not use one word in handing down the Dharma, for his was a “silent transmission of the seal of the mind.”146

After listing the Indian Patriarchs, this work then proceeds to the individual biographies of Bodhidharma and the other Ch’an Masters. In general, it details events which have appeared in earlier works. Bodhidharma is identified, as usual, as a prince from India, and we are told that he taught the “sudden doctrine,” but no mention is made of his transmission of either the Laṅkāvatāra or the Diamond Sutra. Several stories of Bodhidharma’s conversations with other priests and laymen are recorded, including his encounter with the Emperor Wu. This legend has by now become entrenched in the Ch’an tradition. We are furnished with a new story, which tells of how Bodhidharma, in transmitting his teaching, gave to one disciple his bones, to another his flesh, and to a third, Hui-k’o, his marrow.147 Again we hear that Bodhidharma gave his own age as one hundred and fifty. The biography concludes with the story that after his death Bodhidharma was seen returning to India, wearing only one shoe, and that the missing shoe was found later in his grave.148 He is said to have left one disciple in India, Prajñāmitra, and three in China.

The biographies of the other Chinese Patriarchs contain slight variations from the earlier versions that have appeared. Most significantly, Hui-neng is accepted as the Sixth Patriarch. Thus, twenty years after the death of Shen-hui, his theories have been adopted by a school of Ch’an which made no attempt to connect its own teachers with Huineng himself. The Li-tai fa-pao chi gives a fairly detailed account of the Sixth Patriarch, quite similar, as we have seen, to that given in the Suzuki text of the Shen-hui yü lu. It then moves on to a discussion of the priests who represent its own school; but before their biographies are given, it furnishes an introductory story.

We are told that on the twentieth day of the second month of Ch’ang-shou 1 (= March 14, 692) the Empress Wu dispatched the secretary Chang Ch’ang-chi as a messenger to Ts’ao-ch’i to summon Hui-neng to court; pleading illness, however, he declined. A second messenger was dispatched in 696 to request that Bodhidharma’s robe be sent to court so that reverence might be done it and offerings made to it. To this Hui-neng assented, and the robe was brought to the palace, much to the empress’ delight. In the seventh month of the next year, Chang Ch’ang-chi was again sent as a messenger, this time to Chih-hsien in Szechuan, with a request that he come to court. Chih-hsien complied. In the year 700, the story continues, Shen-hsiu, Hui-an, Hsüan-tse, and Hsüan-yüeh were all called to court. Chih-hsien was conspicuous for the conversions he made, and for his knowledge of the Dharma, but falling ill, he requested permission to return home. His wishes were granted, and when he left he was given Bodhidharma’s robe to take back with him to Szechuan. Then we are told, in the eleventh month of 707149 the Empress Wu sent the chief palace attendant, Hsüeh Chien, to Hui-neng with a gift of a special robe and 500 bolts of silk.

This preposterous story, patently an invention designed to advocate the legitimacy of the school descended from Chih-hsien and to make the claim that the robe, symbolic of the transmission, was in Szechuan, appears nowhere but in this work. History continues to be invented by the various Ch’an schools, and the Empress Wu seems to have been the most popular subject for the attribution of proclamations and requests to eminent priests, inviting them to serve within the palace precincts.

With this new legend established, at least to its own satisfaction, the Li-tai fa-pao chi moves into the biographies of Chih-hsien and his school. As has been noted before, no attempt is made to link the school with that of Hui-neng. Chih-hsien,150 we are told, was a native of Ju-nan in Honan. At thirteen he left home to enter a monastery, and first studied the canonical works under the famous Hsüan-tsang. Later, hearing of the Fifth Patriarch, he discarded his books and went to study under him. After leaving Hung-jen, he went to the Te-ch’un Temple in Szechuan, where he busied himself making converts, and wrote several commentaries, including one on the Heart Sutra. In 697 he was called to court by Empress Wu, where the events described above took place. In 702 he called his disciple Ch’u-chi to his side and handed to him Bodhidharma’s robe, which the Empress Wu had entrusted to him. He passed away at the age of ninety-four on the sixth day of the seventh month of Chang-an 2 (= August 4, 702).

Ch’u-chi,151 his disciple, was a native of Mien-chou152 of the family T’ang and he is occasionally referred to as the “Priest T’ang” (T’ang ho-shang). Following his father’s death, Ch’u-chi left home at the age of ten, going to Chih-hsien for instruction. For a while he stayed at other temples, but eventually returned to his Master in Szechuan, where he spent some twenty years in making conversions among the general populace. The date of his death is given as 732 and his age as sixty-eight.153 Although not expressly stated, it is evident that his teachings contained various elements of the Amidist tradition. Among his disciples was Ch’eng-yüan,154 who became a prominent teacher in the Pure Land school.

Ch’u-chi handed down Bodhidharma’s robe to his disciple Wu-hsiang.155 Of Korean origin, he is commonly referred to as the “Priest Chin” (Chin ho-shang). The biography given in the Li-tai fa-pao chi is a lengthy one, and contains various details of his teaching. He is said to have based his doctrine on three phrases: no recollection, no thought, and no forgetting, and to have advocated a form of invocation which required a gradual lowering of the voice as the intonation progressed. Here again, Pure Land elements are evident in the teaching of this school. After coming to China, Wu-hsiang spent two years with Ch’u-chi, left him for a while, but later returned, eventually receiving Bodhidharma’s robe from his Master. He lived at the Ching-ch’üan Temple in Szechuan for over twenty years, and was eminently successful in gaining converts. His death date is given as the nineteenth day of the fifth month of Pao-ying 1 (= June 15, 762) at the age of seventy-nine.