Chapter 1. The JavaScript Revolution

JavaScript is arguably the most important programming language on earth. Once thought of as a toy, JavaScript is now the most widely deployed programming language in history. Almost everyone with a computer or a smartphone has all the tools they need to execute JavaScript programs and to create their own. All you need is a browser and a text editor.

JavaScript, HTML, and CSS have become so prevalent that many operating systems have adopted the open web standards as the presentation layer for native apps, including Windows 8, Firefox OS, Gnome, and Google’s Chrome OS. Additionally, the iPhone and Android mobile devices support web views that allow them to incorporate JavaScript and HTML5 functionality into native applications.

JavaScript is also moving into the hardware world. Projects like Arduino, Tessel, Espruino, and NodeBots foreshadow a time in the near future where JavaScript could be a common language for embedded systems and robotics.

Creating a JavaScript program is as simple as editing a text file and opening it in the browser. There are no complex development environments to download and install, and no complex IDE to learn. JavaScript is easy to learn, too. The basic syntax is immediately familiar to any programmer who has been exposed to the C family syntax. No other language can boast a barrier to entry as low as JavaScript’s.

That low barrier to entry is probably the main reason that JavaScript was once widely (perhaps rightly) shunned as a toy. It was mainly used to create UI effects in the browser. That situation has changed.

For a long time, there was no way to save data with JavaScript. If you wanted data to persist, you had to submit a form to a web server and wait for a page refresh. That hindered the process of creating responsive and dynamic web applications. However, in 2000, Microsoft started shipping Ajax technology in Internet Explorer. Soon after, other browsers added support for the XMLHttpRequest object.

In 2004, Google launched Gmail. Initially applauded because it promised users nearly infinite storage for their email, Gmail also brought a major revolution. Gone were the page refreshes. Under the hood, Gmail was taking advantage of the new Ajax technology, creating a single-page, fast, and responsive web application that would forever change the way that web applications are designed.

Since that time, web developers have produced nearly every type of application, including full-blown, cloud-based office suites (see Zoho.com), social APIs like Facebook’s JavaScript SDK, and even graphically intensive video games.

All of this is serving to prove Atwood’s Law: “Any application that can be written in JavaScript, will eventually be written in JavaScript.”

Advantages of JavaScript

JavaScript didn’t just luck into its position as the dominant client-side language on the Web. It is actually very well suited to be the language that took over the world. It is one of the most advanced and expressive programming languages developed to date. The following sections outline some of the features you may or may not be familiar with.

Performance

Just-in-time compiling: in modern browsers, most JavaScript is compiled, highly optimized, and executed like native code, so runtime performance is close to that of software written in C or C++. Of course, there is still the overhead of garbage collection and dynamic binding, so it is possible to do certain things faster; however, the difference is generally not worth sweating over until you’ve optimized everything else. With Node.js (a high-performance, evented, server-side JavaScript environment built on Google’s highly optimized V8 JavaScript engine), JavaScript apps are event driven and nonblocking, which generally more than makes up for the code execution difference between JavaScript and less dynamic languages.

Objects

JavaScript has very rich object-oriented (OO) features. The JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) standard used in nearly all modern web applications for both communication and data persistence is a subset of JavaScript’s excellent object-literal notation.

JavaScript uses a prototypal inheritance model. Instead of classes, you have object prototypes. New objects automatically inherit methods and attributes of their parent object through the prototype chain. It’s possible to modify an object’s prototype at any time, making JavaScript a very flexible, dynamic language.

Prototypal OO is so much more flexible than classical inheritance that it’s possible to mimic Java’s class-based OO and inheritance models in JavaScript virtually feature for feature, and in most cases, with less code. The reverse is not true.

Contrary to common belief, JavaScript supports features like encapsulation, polymorphism, multiple inheritance, and composition. You’ll learn more about these topics in Chapter 3.

Syntax

The JavaScript syntax should be immediately familiar to anybody who has experience with C-family languages, such as C++, Java, C#, and PHP. Part of JavaScript’s popularity is due to its familiarity, though it’s important to understand that JavaScript behaves very differently from all of these under the hood.

JavaScript’s object-literal syntax is so simple, flexible, and concise, it was adapted to become the dominant standard for client/server communication in the form of JSON, which is more compact and flexible than the XML that it replaced.

First-Class Functions

In JavaScript, objects are not a tacked-on afterthought. Nearly everything in JavaScript is an object, including functions. Because of that feature, functions can be used anywhere you might use a variable, including the parameters in function calls. That feature is often used to define anonymous callback functions for asynchronous operations, or to create higher order functions (functions that take other functions as parameters, return a function, or both). Higher-order functions are used in the functional programming style to abstract away commonly repeated coding patterns, such as iteration loops or other instruction sets that differ mostly in the variables or data they consume.

Good examples of functional programing include functions like

.map(), .reduce(), and

.forEach(). The Underscore.js library contains many useful functional utilities. For simplicity,

we’ll be making use of Underscore.js in this book.

Events

Inside the browser, everything runs in an event loop. JavaScript coders quickly learn to think in terms of event handlers, and as a result, code from experienced JavaScript developers tends to be well organized and efficient. Operations that might block processing in other languages happen concurrently in JavaScript.

If you click something, you want something to happen instantly. That impatience has led to wonderful advancements in UI design, such as Google Instant and the groundbreaking address lookup on The Wilderness Downtown. (“The Wilderness Downtown” is an interactive short film by Chris Milk set to the Arcade Fire song, “We Used To Wait.” It was built entirely with the latest open web technologies.) Such functionality is powered by Ajax calls that do their thing in the background without slowing down the UI.

Reusability

JavaScript code, by virtue of its ubiquity, is the most portable, reusable code around. What other language lets you write the same code that runs natively on both the client and the server? (See Getting Started with Node and Express to learn about an event-driven JavaScript environment that is revolutionizing server-side development.)

JavaScript can be modular and encapsulated, and it is common to see scripts written by six different teams of developers who have never communicated working in harmony on the same page.

The Net Result

JavaScript developers are at the heart of what may be the single biggest revolution in the history of computing: the dawn of the realtime web. Messages pass back and forth across the net, in some cases with each keystroke, or every move of the mouse. We’re writing applications that put desktop application UI’s to shame. Modern JavaScript applications are the most responsive, most socially engaging applications ever written—and if you don’t know JavaScript yet, you’re missing the boat. It’s time to get on board, before you get left behind.

Anatomy of a Typical Modern JavaScript App

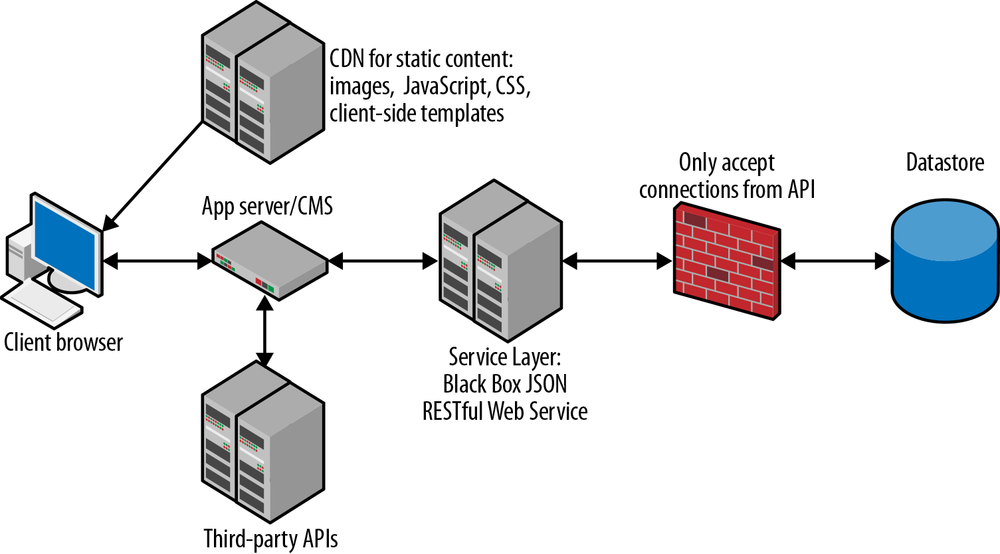

While every app is unique, most share some common concerns, such as hosting infrastructure, resource management, presentation, and UI behaviors. This section covers where these various elements typically live in the application and the common mechanisms that allow them to communicate.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure can come in many flavors and have lots of different caching mechanisms. Generally, it consists of (back to front):

A data store

A virtual private network (VPN) or firewall (to protect the data store from unauthorized access)

A black box JSON RESTful Web Service Layer

Various third-party APIs

An app server/content management system (CMS) to route requests and deliver pages to the client

A static content deliver network (CDN) for cached files (like images, JavaScript, CSS, and client-side templates)

The client (browser)

To see how these generally fit together, see Figure 1-1.

Most of these components are self explanatory, but there are some important points that you should be aware of concerning the storage and communication of application data.

The data store is just like it sounds: a place to store your application data. This is commonly a relational database management system (RDBMS) with a Structured Query Language (SQL) API, but the popularity of NoSQL solutions is on the rise. In the future, it’s likely that many applications will use a combination of both.

JSON: Data Storage and Communication

JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) is an open standard developed by Douglas Crockford that specifies a subset of the native JavaScript object-literal syntax for use in data representation, communication, and storage.

Prior to the JSON specification, most client-server communications were being delivered in much more verbose XML snippets. JavaScript developers often work with JSON web services and frequently define internal data using JSON syntax.

Take this example message, describing a collection of books:

[{"title":"JavaScript: The Good Parts","author":"Douglas Crockford","ISBN":"0596517742"},{"title":"JavaScript Patterns","author":"Stoyan Stefanov","ISBN":"0596806752"}]

As you can see, this format is nearly identical to JavaScript’s object-literal syntax, with a couple important differences:

NoSQL Data Stores

Prior to the advent of Extensible Markup Language (XML) and JSON data stores, nearly all web services were backed by RDBMS. An RDBMS stores discrete data points in tables and groups data output using table lookups in response to SQL queries.

NoSQL data stores, in contrast, store entire records in documents or document snippets without resorting to table-based structured storage. Document-oriented data stores commonly store data in XML format, while object-oriented data stores commonly employ the JSON format. The latter are particularly well suited to web application development, because JSON is the format you use to communicate natively in JavaScript.

Examples of popular JSON-based NoSQL data stores include MongoDB and CouchDB. Despite the recent popularity of NoSQL, it is still common to find modern JavaScript applications backed by MySQL and similar RDBMSs.

RESTful JSON Web Services

Representational State Transfer (REST) is a client-server communication architecture that creates a separation of concerns between data resources and user interfaces (or other data resource consumers, such as data analysis tools and aggregators). Services that implement REST are referred to as RESTful. The server manages data resources (such as user records). It does not implement the user interface (look and feel). Clients are free to implement the UI (or not) in whatever manner or language is desired. REST architecture does not address how user interfaces are implemented. It only deals with maintaining application state between the client and the server.

RESTful web services use HTTP verbs to tell the server what action the client intends. The actions supported are:

This might look familiar if you’re familiar with CRUD (create, retrieve, update, delete). Just remember that in the REST mapping, update really means replace.

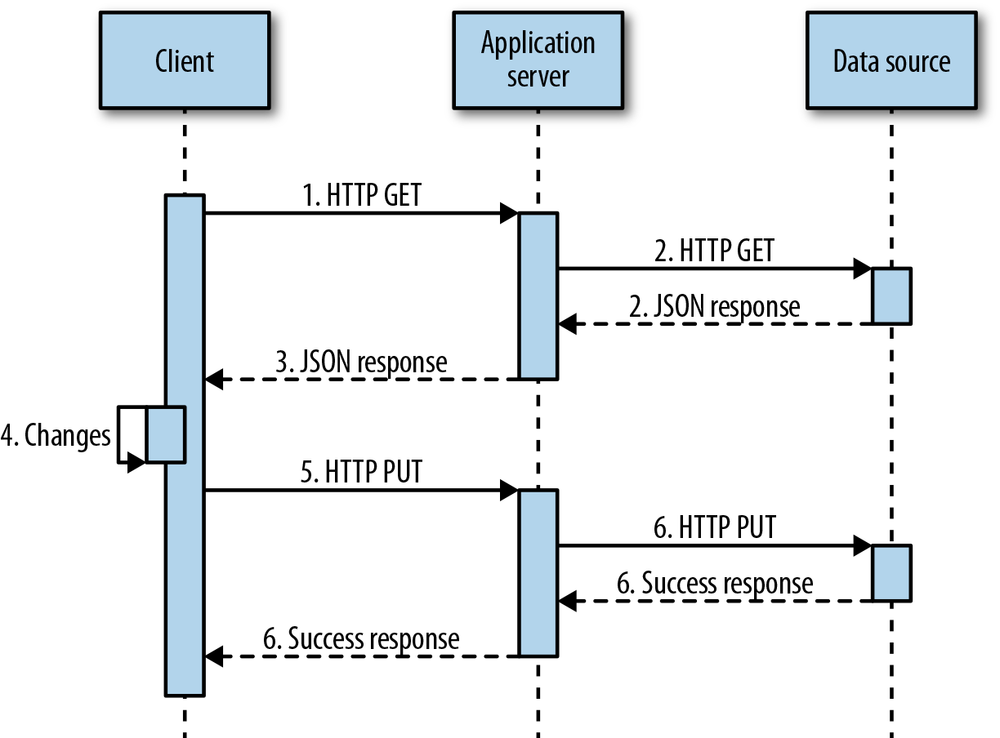

Figure 1-2 shows a typical state transfer flow.

The client requests data from the server with an HTTP GET request to the resource uniform resource indicator (URI). Each resource on the server has a unique URI.

The server retrieves the data (typically from a database or cache) and packages it into a convenient representation for the client.

Data is returned in the form of a document. Those documents are commonly text strings containing JSON encoded objects, but REST is agnostic about how you package your data. It’s also common to see XML-based RESTful services. Most new services default to JSON formatted data, and many support both XML and JSON.

The client manipulates the data representation.

The client makes a call to the same endpoint URI with a PUT, sending back the manipulated data.

The resource data on the server is replaced by the data in the PUT request.

It’s common to be confused about whether to use PUT or POST to change a resource. REST eases that confusion. PUT is used if the client is capable of generating its own safe IDs. Otherwise, a POST request is always made on a collection to create a new resource. In this case, the server generates the ID and returns it to the client.

For example, you might create a new user by hitting

/users/ with a POST request, at which point the server will

generate a unique ID that you can use to access the new resource at

/users/. The server will

return a new user representation with its own unique URI. You shouldn’t

modify an existing resource with POST; you can add only children to

it.userid

Use PUT to change the user’s display name by hitting

/users/ with the updated

user record. Note that this will completely replace the user record, so

make sure that the representation you PUT contains everything you want

it to contain.userid

You can learn more about working with REST in Chapter 8.