XI

Indian Industry: Prospects and Challenges

Rajiv Kumar

India’s industrial development since Independence has charted its own rather unique path. Industrialization began in the early nineteenth century when the first textile mill was established at Fort Gloster near Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1814, followed by many such mills in Bombay (Mumbai) and Ahmedabad. Industrialization came of age with the commencement of steelmaking by the Tatas in Jamshedpur in 1907. This put India among the early ‘industrializers’ outside Europe and North America. But India’s industrialization was unable to benefit from either this early start or the distinct advantage of catering to a large and growing domestic market and emerging markets in neighbouring Asia.

Several factors, both external and self-inflicted, led to the ‘arrested development’ of the industrial and manufacturing sector in India. These were in broad chronological order: the colonial administration’s anti-colony bias;1 upheaval and partition of India during Independence; central planning and Soviet-style heavy industrialization;2 dysfunctional regulation over capacity expansion and technology upgradation;3 growth-retarding inverted protectionism (with higher import duties on inputs compared to finished products); and export pessimism.4 These policy-driven shifts and swings have led to underperformance by Indian industry, in terms of its share in the Indian economy, aggregate employment and stagnant share in external markets.

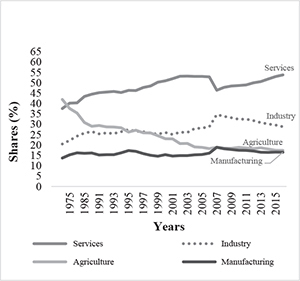

The liberalization of 1991 generated strong optimism on the much-needed expansion of the manufacturing and industrial sectors. This optimism has been unfortunately disproven. The liberalization led to the take-off of IT and IT-enabled services (ITES) but hardly impacted manufacturing and industry, with their shares in GDP stagnating between 16 to 28 per cent during the post-liberalization period (Appendix 2). The services sector took up the decline in the share of agriculture by raising its share from 45.2 to 53 per cent during this period (Figure 7A) with IT revenues increasing from USD 2 billion in 1994–95 to USD 3.1 billion in 2004–05 and further to USD 119 billion in 2014–15.5

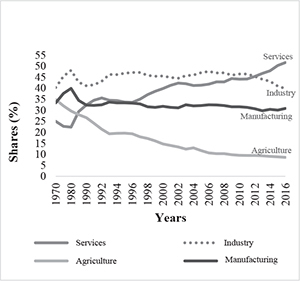

Apparently, India side-stepped the second phase of the Rostowian development path6 with the secondary sector being replaced by the tertiary sector as the driver of growth and absorber of surplus labour from agriculture. The shift occurred even when India’s per capita incomes were low enough to have generated growth from industry as opposed to services. The contrast is stark compared to China’s manufacturing share in GDP ranging between 32.2 and 30 per cent during 1991–2015. The next section discusses the relative stagnation of the industrial and manufacturing sectors during the twenty-five years following liberalization.

Successive governments since prime minister Vajpayee’s in 1998 have refused to accept the slow growth in manufacturing. India’s political leadership across party lines have emphasized accelerated manufacturing sector growth as the key for achieving high GDP growth and full employment, facilitating its transition from a low to an upper middle income economy. The emphasis on manufacturing, as pronounced by successive prime ministers, is summarily reflected in the objective of raising the share of manufacturing in GDP from 16 per cent to 25 per cent and employing as many as 100 million workers or approximately 20 per cent of the total workforce. This target is repeated on multiple occasions despite the growing evidence that given the trends in global trade and technology flows, the share of manufacturing in GDP of emerging economies is likely to plateau at a much lower level than those of advanced economies and by China.7

Figure 7A: Change in Sector Shares in India (1970–2016)

Figure 7B: Change in Sector Shares in China (1970–2016)

Source: World Development Indicators Database, World Bank, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, and National Bureau of Statistics of China.

The critical question facing Indian policymakers is whether it is feasible to achieve the ambitious target for manufacturing given that automation, robotization, digital networking, including ‘Internet of Things’ and advanced machine interface, are reducing labour intensity in and employment potential of the manufacturing and industrial sectors. The consequential ‘re-shoring’ of manufacturing capacities back to advanced economies, which had earlier relocated these industries to emerging economies with lower wage costs, has manifold implications for Indian industry, as discussed later, along with some major emerging trends in industrial automation often referred to as ‘Industry 4.0’.

The last section in this article argues that emerging trends in automation and re-shoring should not propel Indian policies to become protectionist for shielding Indian manufacturing. This would be a Luddite response destined to fail in meeting the manufacturing sector’s growth and employment generation targets. Such an inward-looking and protectionist strategy would further shrink the Indian manufacturing sector for two strong reasons. First, as a founding member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and having joined several bilateral and regional free trade agreements, India will be forced to increase tariff and non-tariff barriers to protect its producers from imports. Indeed, a reversal from existing levels of globalization is not feasible and the domestic manufacturing unable to compete with imports will shrivel further.

Second, in a self-reinforcing manner, complete reliance on domestic demand will not permit adoption of frontline technologies and production processes that generate economies of scale and lower costs, necessary for making Indian manufacturing globally competitive. This would spell the slow but certain demise of the Indian manufacturing industry. The last section provides an alternative policy direction for making Indian manufacturing globally competitive and better equipped for meeting its ambitious objectives.

Stylized Features of the Indian Manufacturing Sector

An overview of the manufacturing sector reveals the following:

- The share of manufacturing in GDP has been around 15 per cent since 1965. Notwithstanding an increase to around 19 per cent in 2007, it declined to around 16 per cent in 2015 (Appendix 2).

- The above share is significantly lower than that of China, which while being as high as 40 per cent in 1980, has consistently been around 33 per cent. Again, in contrast to India, manufacturing made up for a lower share of agriculture, as well as the labour displaced by the latter (Appendix 3).

- Sub-sectoral composition of manufacturing output in India has been somewhat lopsided and not in line with other emerging economies.8 Relatively labour-intensive industries like light engineering, garments and leather goods have grown much slower than capital-intensive chemical and petrochemical industries. This has been policy-induced and prevented India from exploiting its comparative or low wages.

- The rather perverse composition of Indian manufacturing is due to dysfunctional government procedures and licencing requirements that critically constrained the growth of manufacturing. For instance, in 2016, India was thirty-ninth and 130th in the global competitiveness business environment indices. These rankings, much worse earlier, did not permit expansion of manufacturing. Services with less dependence on licencing and regulations performed much better since 1991.

- The lopsided growth of manufacturing industries prevented India from capturing global markets through labour-intensive exports. The share of Indian manufactured exports in global manufactured exports increased from 0.5 per cent to 1.5 per cent during 1991–2015. In contrast, China’s manufactured exports increased their share from around 2 per cent to more than 18 per cent in 2015 as a result of higher focus on labour-intensive industries.

- The share of manufactured exports in India’s total exports has remained relatively unchanged at around 70 per cent between 1990 and 2015.

- Regionally, manufacturing has remained inequitable despite the liberalization of 1991 and further reforms. Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka account for more than 50 per cent of the manufacturing output since 1970–71. The share of the weakest ten states in manufacturing has increased from 10 per cent in 1970–71 to only 15 per cent in 2014–15.9

- Overall, the industrial sector’s share in total employment increased from 15.4 per cent in 1999 to 24.8 per cent in 2012. But manufacturing’s share in employment over eighteen years (1993 to 2010) remained stagnant at around 11 per cent. India seems to have reached the plateau in the manufacturing sector’s share in employment far earlier in its development journey.

The twin questions facing us are: Can India reverse the trend of low share of employment through focused policy intervention? And does India represent the emerging global trend of manufacturing’s contribution to GDP and employment plateauing at substantially lower per capita income levels than those in advanced economies or East Asian ‘tiger economies’, including China?

Current Trends in Global Technology and Production Networks

The global economy is experiencing the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’. Industry 4.0 has demonstrated the ability to replace not only routine but also complex and intelligent human intervention in both manufacturing and services. Industry 4.0 has resulted in some remarkable changes.

- Energy is becoming cheaper and cleaner with countries committing to 100 per cent energy from renewables. Smart grids are likely to dispense large generating plants on the one hand and establish a time-of-the-day energy market on the other.

- The onset of 3D printing might replace serpentine assembly lines for several industries by final assembly or manufacturing in closest proximity to the consumer.

- E-commerce has already disrupted wholesale and retail trade. More transformative changes in the pipeline would alter the logistics needs of manufacturing, and manufacturing itself. Mass customization will be on offer widely.

- Robotization, greater use of sensors and artificial intelligence (AI), backed by ‘big data’, has radically altered factor proportions in manufacturing. Labour is being rapidly replaced by ‘inter-facing machines’ reducing the labour intensity of traditional labour-intensive industries (e.g. textiles, leather, garments)—once considered impenetrable by AI and robots.

- Industry 4.0 is resulting in ‘re-shoring of industries’ with labour-intensive industries being attracted back to advanced economy locations to operate in close proximity to demand centres. This will transform the character of global production networks and the comparative advantage of emerging market economies like India.

- Competitive advantage in global manufacturing will henceforth be determined almost entirely by the countries’ ability to establish world-class infrastructure and acquire high-quality, knowledge-intensive human resources that can adapt to changing technology.

- The days of sequential catching up from initially starting with hugely labour-intensive manufacturing operations to semi-assemblies and subsequently to high technology and design-intensive manufacturing may be behind us.

Challenges and Prospects for Indian Manufacturing: Some Recommendations

It is far too optimistic to expect that the Indian manufacturing sector will succeed in contributing a quarter of GDP or generate 100 million jobs over the next two decades or more. The sheer pace of sustained acceleration required to achieve these targets is staggering. With the annual GDP growth expected to be in the range of 7–9 per cent in real terms, manufacturing must grow by 10–12 per cent in real terms, or more than 15 per cent in nominal terms, for its share to start rising. In the past, there have been only seven years when manufacturing attained high, double-digit growth (Figure 8). With barely 11–13 per cent of the workforce engaged in the formal manufacturing sector given the stagnation in jobs and job losses in recent years, it would be a real challenge to generate sufficiently large opportunities for employing 20 per cent or 100 million additional workers in the manufacturing sector.

Figure 8: Annual Growth Rates of the Manufacturing Sector in India (1970–2016)

Source: World Development Indicators Database, World Bank, and Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

The employment challenge is compounded by the strengthening of Industry 4.0 trends lowering labour intensities across the board. Rising automation and robotization has been severe on employment of unskilled and even semi-skilled workers in manufacturing. Manufacturing will henceforth see the emergence of production processes that integrate software and hardware in machines and require highly-skilled workers to be sufficiently flexible for adapting to evolving technologies.

The emerging trends have given rise to strong ‘manufacturing pessimism’ in emerging economies, including India. This is perhaps needed to balance the optimism of those who conceive of manufacturing growth in India as replicating the Chinese experience of the last three decades. That is simply not possible. Conditions in domestic labour markets, which prevent wages in India from matching those in countries with semi-authoritarian regimes, increasing use of hybrid and automated technologies, and growing pressure from global competition based on mass customization and rapid product innovation, rule India out of the phase of becoming an exporter of mass-produced, low-quality and labour-intensively manufactured products. An alternative strategy needs to be devised for accelerating the manufacturing sector growth.

Unfortunately, in the current and evolving global scenarios, there are no easy fixes to increasing the share of manufacturing or for it to generate a large number of new jobs. Both the government and industry must recognize that they will have to work closely together for Indian manufacturing to achieve global competitiveness, which is a sine qua non for ramping up domestic manufacturing capacity.

India must try and achieve greater integration of its manufacturing capacities with regional and global production networks for increasing the share of intra-industrial trade in its total trade. This has two important policy implications. One, the prevailing infrastructure deficit, putting Indian manufacturing at a significant disadvantage vis-a-vis its competitors and discouraging foreign investors from choosing India as an export hub, must be eliminated at the earliest. The government will have to take the lead in this as physical infrastructure is a public good where social returns greatly outweigh private returns. Two, foreign trade procedures must be streamlined and made seamless for encouraging intra-industry trade, which accounts for more than two-thirds of global trade flows. Intra-industry trade, in which emerging economies manufacture and export relatively low technology components and sub-assemblies, perhaps, remains an area where India can see greater labour absorption and expansion of manufacturing capacities.

The brunt of component manufacturing and exports should be borne by SMEs, many numbers of which are ‘informal’. These must be formalized and provided access to commercial bank credit at reasonable terms; made attractive to foreign joint venture partners; and given access to information about global markets and technology trends. This requires a major shift in the focus of industrial policy by making it focused on SMEs. The formalization and, more importantly, modernization of the tier two and three of private-sector firms, predominantly unlisted and working as proprietary and partnership companies, could see an exponential growth in domestic manufacturing capacities in the coming years. The focus on intra-industry trade and the ‘next 500’ companies offers a good bet for accelerating manufacturing growth and employment generation in India.

Greater attention must be devoted to strengthening the sources of the knowledge economy. This implies greater attention to R & D, especially directed towards product innovation. Total R & D expenditure in India is woefully low at barely 1 per cent of GDP, compared to more than 3 per cent in Japan and the United States and 4 per cent in Korea. The Indian private corporate sector hardly contributes to this abysmally low R & D expenditure. This must change. Government policy should aim to provide sustained incentives for product innovation as opposed to process or cost-reducing form of ‘incremental innovation’ that presently dominates corporate R & D expenditure. Strengthening of the intellectual property regime; greater collaboration amongst public and private corporate R & D activities; and lowering of policy-induced barriers for scaling up operations could be possible policy responses for addressing this perceptible weakness in Indian manufacturing, especially in view of the immense breakthrough opportunities offered by the ongoing fourth global technology revolution.

A special effort is necessary to push back global protectionist tendencies being echoed domestically. India must participate more forcefully in the G-20 platform for protecting the multilateral liberal global trading regime that has delivered the longest and most robust rise in living standards of global population in the post-Second World War period. The perception in some quarters that a liberal order determining global trade, technology and financial flows is detrimental to Indian manufacturing is misplaced. That would stunt Indian manufacturing capacities and capabilities as domestic firms will neither achieve economies of scale for becoming globally competitive nor acquire critical new technologies essential for increasing shares in the global market. The inevitable result will be slow and certain shrinking of domestic manufacturing, which will be unable to withstand import competition.

Instead, policy should be directed to urgently address critical constraints making Indian manufacturing globally uncompetitive. Greater focus should be on productivity-enhancing policy measures at reasonable price points. This includes addressing infrastructure deficits, including transport (roads, railways, ports and airports); electricity availability and its quality; and logistics. Notwithstanding some improvements over the past two decades, significant gaps remain, especially as one moves away from metros and state capitals.

There is a critical need to improve the level of trust between the government and business. This lack of mutual trust results in over-regulation and excessive compliance burdens on private businesses, and leads to extensive rent-seeking opportunities. The prevailing environment of mistrust and over-compliance explains the inability of many SMEs to scale up operations and become globally competitive. This is neatly summed up in the terse remark that conditions in India spawned companies that are not born as regular start-ups that grow over time but as ‘midgets’ that remain stunted and globally uncompetitive.

The private sector can and must play its due role in building the trust-based relationship with the government, which is a sine qua non for achieving global competitiveness, pushing innovative growth strategies and successfully integrating with global and regional production networks. For starters, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi has suggested, the Institute of Chartered Accountants as the established self-regulating and self-certifying institution should enforce corporate governance and financial accountability as required under existing statutes.

Apex industry organizations like the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) and the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and indeed the principal regional ones as well, must disqualify members charged with misdemeanours and evasion of statutory compliances. This process of self-regulation has been effective in several countries and helps in improving prospects of collaboration between public and private sector and attracting FDI, which may then have greater confidence in forming joint-ventures with Indian companies.

The issue of reducing mutual mistrust and laying the basis for greater collaboration and partnership between the government and business has not received adequate attention either in policymaking or in academic enquiries. It is a critical driver of India’s manufacturing prospects and deserves greater focus going forward. These improvements can lead to the emergence of a true ‘India Inc. coalition’, which is presently confined to rhetoric. Creation of an effective India Inc. coalition is one of the principal conditions for expanding India’s share in global manufacturing and for its firms to achieve sustained global competitiveness.