15

WILLIAM Z. RIPLEY AND THE RACES OF EUROPE

Francis Amasa Walker’s famous cliché “beaten men from beaten races” played well in white race science, but Walker was hardly out there alone crying in the wilderness. Scores of others—men like the author and lecturer John Fiske and scholars from high academia, like the era’s leading sociologist, Edward A. Ross, and the pioneering political scientist Francis Giddings of Columbia—joined Walker in pushing northern European racial superiority over new immigrant masses. At the other end of the spectrum, the American Federation of Labor also drew the line against the new immigrants as “beaten men of beaten races.”1 But Walker, who was to die in 1897, stood highest in influence, practically dictating how Americans would rank white peoples for decades, a period that introduced William Z. Ripley.

Originally from Medford, Massachusetts, William Z. Ripley (1867–1941), like Walker and Lodge, advertised his New England ancestry: his middle name, Zebina, he said, honored five generations of Plymouth ancestors.* Ripley contrasted “our original Anglo-Saxon ancestry in America” with that of “the motley throngs now pouring in upon us,” and, like Walker, he attended to his manly and nattily dressed appearance.2 (See figure 15.1, William Z. Ripley.) With Ripley it was smart minds in handsome bodies all over again—and, one might add, education and connections.

After gaining a bachelor’s degree in engineering from MIT, Ripley took a Ph.D. in economics at Columbia, writing a dissertation on the economy of colonial Virginia. After two years’ lecturing at MIT and Columbia, Ripley found himself at somewhat loose ends in 1895. He needed a better-paying job, and an aging Francis Walker needed a scientific classification of American immigrants. Walker chose Ripley, his favorite student, and Ripley seized this opportunity to codify the gaggle of immigrants.3*

Ripley later said that The Races of Europe took nineteen months of work. To a scholar these days that seems not very long. Working with his suffragist wife, Ida S. Davis, and librarians at the Boston Public Library, Ripley synthesized the writings of hundreds of anthropologists.4† John Beddoe in England and Joseph Deniker and Georges Vacher de Lapouge in France proved especially helpful. European anthropologists had been compulsively measuring their populations for decades, offering Ripley tens of thousands of detailed measurements, charts, maps, and photographs. Ripley used them all. Such exhaustive scholarship, together with the “Ph.D.” attached to Ripley’s Anglo-Saxon name on the title page, endowed The Races of Europe with a glowing scientific aura.

Ripley’s work first reached the public as a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1896. Earlier in the century the Lowell Institute had offered its podium to likely speakers on race such as George Gliddon (Josiah Nott’s collaborator) and Louis Agassiz (soon to join the Harvard faculty). The New York publisher Appleton issued the lectures serially in Popular Science Monthly and then published a generously illustrated book in 1899.*

Fig. 15.1. William Z. Ripley, professor of economics, Harvard University, ca. 1920.

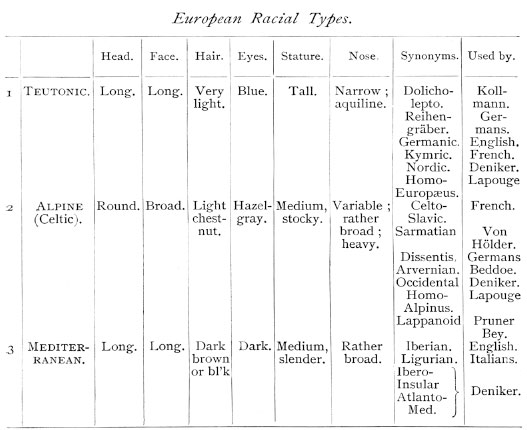

Weighing in at 624 pages of text, 222 portraits, 86 maps, tables, and graphs, and a bibliographical supplement of more than two thousand sources in several languages, the sheer heft of The Races of Europe intimidated and entranced readers, blinding most of them to its incoherence. Ripley himself may have been blinded by the magnitude of his task, aiming as he did to reconcile a welter of conflicting racial classifications that could not be reconciled. (See figure 15.2, Ripley’s “European Racial Types.”) In this table Ripley presents “traits” he considered important—head shape, pigmentation, and height—along with the multiple taxonomies posited by various scholars.

One glaring taxonomic dilemma appears in the inclusion of “Celtic,” in parentheses, beneath “Alpine.” Anthropologists had long struggled to sort out the relationship between ancient and modern Celts, between the Celtic regions of Europe such as Ireland and Brittany, and between ancient and modern Celtic languages such as Gaelic. Was France a Celtic nation? Yes and no. French Republicans embraced their nation’s revolutionary heritage, identifying with such glorious ancient Celtic heroes as Vercingetorix, the tragic protagonist of Caesar’s Gallic War.5 Royalists like Alexis de Tocqueville and his companion Gustave de Beaumont, in contrast, proudly claimed descent from Germanic conquerors. Beaumont, we remember, gave his French protagonist in Marie the Frankish name Ludovic rather than the more familiar French Louis.

Ripley’s parenthesis does not solve the Celtic problem, and he stoops to insert Georges Vacher de Lapouge (a cranky, reactionary librarian at a provincial French university whom we will encounter again later) into the list of authorities. Ripley thereby conferred a measure of scientific recognition, although Lapouge’s fanatic Aryan/Teutonic chauvinism destroyed his standing in France. Questionable scholarship aside, Ripley had set out to transcend “the current mouthings” of the racist lunatic fringe, and his thoroughness inspired confidence for years. Ordinary readers judged his book scientific, and anthropologists hailed his methodology.

Fig. 15.2. “European Racial Types,” in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (1899).

NOTHING EVER got truly settled in race science, but Ripley came close. How many European races were there? Ripley says three: Teutonic, Alpine, and Mediterranean. What criteria to use? Following accepted anthropological science, Ripley chooses the cephalic index (the shape of the head; breadth divided by length times 100), “one of the best available tests of race known.”6 Add to that information about height and pigmentation, and he has nailed each of the three white races:

Teutonics: tall, dolichocephalic (i.e., long-headed), and blond;

Alpines: medium in stature, brachycephalic (i.e., round-headed), with medium-colored hair;

Mediterraneans: short, dolichocephalic (i.e., long-headed), and dark.

The cephalic index was not new. In fact, a real European scholar, the Swedish anthropologist Anders Retzius, had invented it in 1842, coining the terms “brachycephalic” to describe broad heads and “dolichocephalic” to describe long heads. The technique quickly took hold in Europe, where researchers took to measuring heads by the tens of thousands.

Anthropologists loved the cephalic index because it seemed to measure something stable, and race theorists demanded permanence. Heads supposedly remained constant across an endless succession of generations. Concentration on the head was not new. A skull, we recall, had inspired Blumenbach’s naming white people “Caucasian.” Samuel George Morton and Josiah Nott had backed up their assertions of white supremacy with Mrs. Gliddon’s drawings of skulls. France’s Paul Broca, his generation’s most renowned anthropologist, also based his race theories on skull measurements.

Retzius and other fans of the cephalic index had no trouble linking head shape with “racial” qualities such as enterprise, beauty, and, of course, intelligence. Theorizing from old skulls, they envisioned primitive, ancient, Stone Age Europeans—often identified as Celts—as brachycephalic and also dark in color. Accepted theory soon held that long-headed dolichocephalics had invaded Europe and conquered these primitive, broad-headed people. A lot of the old natives were still around, people considered backward, such as the brachycephalic Basques, Finns, Lapps, and quite a few Celts; they were still assumed to be primitive natives, like peasants and other supposedly inert groups.*

Following the English anthropologist John Beddoe, Ripley gingerly notes “the profound contrast which exists between the temperament of the Celtic-speaking and the Teutonic strains in these [British] islands…. The Irish and Welsh are as different from the stolid Englishman as indeed the Italian differs from the Swede.”7 This idea of temperament as a racial trait was based on a perversion of Darwinian evolution. With a perfectly straight face anthropologists reasoned that evolution operated on entire races (not individuals or breeding populations), that races had personalities, and that physical measurements of heads betokened racial personality.

Over time the cephalic index both dominated as a symbol of race and became a two-edged sword when color was added to it. Long-headed people, “dolichocephalics,” for instance, should be light and Teutonic (good) or dark and Mediterranean (bad). Alpines (maybe middling, maybe bad) were supposed to be brownish and brachycephalic. These correlations counted as “harmonic” correspondence. Rather than deal with people who did not fit the pattern, such as blond Alpines, race-minded anthropologists them deemed “disharmonic” and then just ignored them. Perfectly “harmonic” Mediterraneans with long heads and dark hair, eyes, and skin also faded from view, because anthropologists judged them to be obviously inferior and therefore of scant interest.

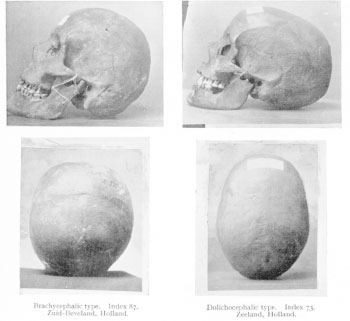

At first all this measuring of heads meant little to most Americans. Slavery and segregation had seen to it that race resided most obviously in skin color, or at least in physical appearance or ancestry that could be classified as black or white. But up-to-date experts stuck to their guns, proffering scientific explanation via visuals. (See figure 15.3, Ripley’s brachycephalic and dolichocephalic skulls.) A caption at the lower left reads, “Brachycephalic type. Index 87. Zuid-Beveland, Holland,” and refers to photographs on the left. On the lower right, “Dolichocephalic type. Index 73. Zeeland, Holland” refers to photographs on the right.* These images were intended to show the difference between a long, dolichocephalic skull with a cephalic index of 73 and a round, brachycephalic skull with a cephalic index of 87.

Fig. 15.3. Brachycephalic and dolichocephalic skulls, in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (1899).

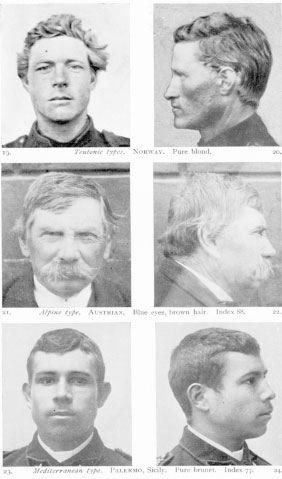

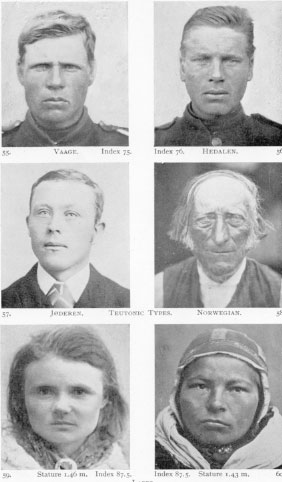

Since ordinary readers rarely encountered skulls in everyday life, and Ripley badly wanted them to understand, he added photographs of racial “types” along with their cephalic indices for further clarification. (See figure 15.4, Ripley’s “Three European Racial Types.”)

The three types are ranked vertically, with the Teutonic inevitably at the top, the Mediterranean inevitably at the bottom, and the Alpine in the middle. The Alpine type’s cephalic index is noted as 88, that is, brachycephalic, and the Mediterranean type’s as 77, that is, dolichocephalic, and the hair and eye color of both types is noted. The two dolichocephalic Norwegian Teutonic types are simply “pure blond,” although, inexplicably, the hair color of the man on the right seems as dark as that of the brachycephalic Austrian and the Sicilian.

The four men depicted as embodiments of the “Three European Racial Types” have no names. Anthropologists of the era saw no need for names. They dealt in ideal “types” that stood for millions of presumably interchangeable individuals.

Fig. 15.4. “The Three European Racial Types,” in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (1899).

RIPLEY’S 624 pages do contain a great deal of information—unfortunately, much of it is contradictory. He recognizes early on that his three racial traits—hair color, height, and cephalic index—are not reliably linked in real people. Short people can be blond; blond heads can be round; long heads can grow dark hair. He admits—and laments—that such complexity destroys any notion of clear racial types. Even his limited number of traits produced an infinity of races and subraces, a taxonomical nightmare.*

To further undermine notions of racial permanency, Ripley concedes that mixture and environment, which most anthropologists preferred to ignore, also affect appearance. Faced with such complexity and so many unknowns, Ripley was, he says, “tempted to turn back in despair.” But he could not let go.8 He did, however, turn his back on the American South, where people white in appearance were discriminated against as Negroes. The U.S. Supreme Court had taken that matter up in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. Homer Plessy, a man who looked white, had been ejected as black from a newly designated white-only car. He sued and lost when the court ruled for segregation. The African American novelist Charles Chesnutt remarked on the “manifest absurdity of classifying men fifteen-sixteenths white as black,” but, absurd or not, that was long to hold true.9* Ripley hardly cared. What happened in the South was less important than how to classify the immigrants pouring into the North. To unravel black and white would have hopelessly snarled his system.

Additional conceptual problems haunt the book’s organization. Definitions—who counts as European people and what constitutes European territory—conflict from one chapter to the next. Ripley is not sure where Europe and its races begin and end. While he dismisses Blumenbach’s notion of a single Caucasian race, The Races of Europe reaches past the territory of the Teutonic, Alpine, and Mediterranean races into Russia, eastern Europe, and western Asia as far as India. Africans appear in the chapter on Mediterranean race. Supposedly the Teutonic race belongs in Scandinavia and Germany; the Mediterranean race, in Italy, Spain, and Africa; and the Alpine race, in Switzerland, the Tyrol, and the Netherlands. Yet another, separate chapter wonders whether Britons originated in the Iberian Peninsula, given that Irish legend names the Spanish king Melisius as the father of the Irish. More taxonomical strangeness was to come.

AS NOTED, Ripley’s three-race system excludes many Europeans, such as Jews, Slavs, eastern Europeans, and Turks. Lapps present the usual quandary: they obviously live in Europe, but they do not look the way anthropologists wanted Europeans to look. Linguists did not face this problem; they put Lapps with Magyrs, Finns, and other speakers of Finnic languages. No problem there. But Ripley rejects this linguistic classification because the Lapps lack beauty: “The Magyrs, among the finest representatives of a west European type,” he says, “are no more like the Lapps than the Australian bushmen.” (See figure 15.5, Ripley’s “Scandinavia.”) The captions under photos of Lapps list only height (4’ 9½” and 4’ 8”) and high cephalic indexes (both 87.5) as confirmation that Lapps are too short in stature and too broad of head.10* Piling it on, Ripley adds an unnamed German anthropologist’s insult that “they [Lapps] are a ‘pathological race.’” Actually, rather than documenting pathology, these photographs demonstrate a Scandinavian variety trumped by racial science’s obsession with purity.

Fig. 15.5. “Scandinavia,” in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (1899).

JEWS POSE another problem. Having long occupied a separate conceptual space within the races of Europe, they must be discussed as a category. At the same time, they are too varied to fit into one of Ripley’s three European races. Recognizing this shortcoming early, Ripley had added a “supplement” on Jews to his Lowell Institute Lectures and articles published in Popular Science Monthly. The Races of Europe allots Jews and Semites a separate chapter.

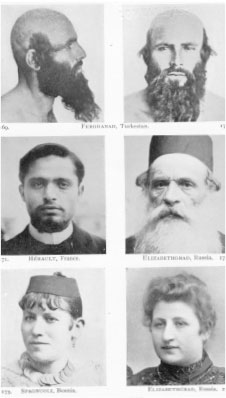

Fig. 15.6. “Jewish Types,” in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (1899).

Anti-Semitic writers had long posited a permanent Jewish race. But Ripley does not like that. Rather, he calls them a “people,” since Jews conform closely to others among whom they live. His photographs of Jewish faces confirm regional variation.11* (See figure 15.6, Ripley’s “Jewish Types.”)

Then consider their noses. Ripley’s bizarre discussion of the stereotypical Jewish nose betrays his uneasiness. He draws three figures to demonstrate how easily “the Jew” may be turned into a Roman. (See figure 15.7, Ripley’s “Behold the Transformation!”) A tortured paragraph explains this conceptual nose job:

The truly Jewish nose is not so often truly convex in profile. Nevertheless, it must be confessed that it gives a hooked impression. This seems to be due to a peculiar “tucking up of the wings,” as Dr. Beddoe expresses it…. Jacobs has ingeniously described this “nostrality,” as he calls it, by the accompanying diagrams: Write, he says, a figure 6 with a long tail

(Fig. 1); now remove the turn of the twist, and much of the Jewishness disappears; and it vanishes entirely when we draw the lower continuation horizontally, as in Fig. 3. Behold the transformation!

Throwing up his hands, Ripley also explains that Jewish noses do not prevail among urban Jews; besides, many non-Jews have noses that look Jewish.12

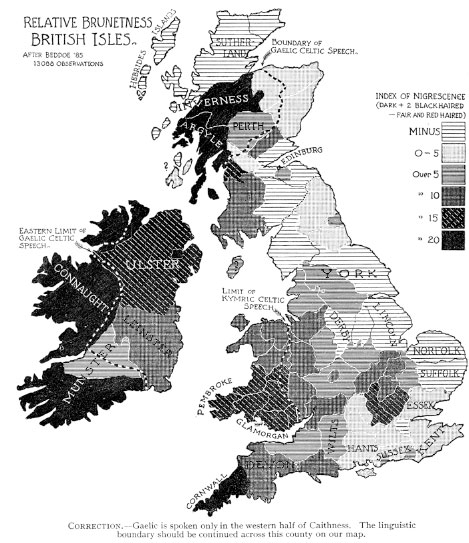

TODAY’S READERS might find intriguing Ripley’s use of a measure of blackness for people of the British Isles. His tool, the “Index of Nigrescence,” had originated with the respected British anthropologist John Beddoe. Over the course of thirty years, Beddoe measured thousands of British heads. Employing impeccable methodology, he analyzed their cephalic indexes, hair, eye, and skin color. Those measurements grounded his classic Races of Britain (1885), whose countless pages of tables convinced Ripley and his generation of scientists that the Irish were dark. Beddoe’s maps and photographs slipped easily into Ripley’s chapter on Britons in The Races of Europe.13 (See figure 15.8, Ripley’s “Relative Brunetness.”)

Fig. 15.7. “Behold the Transformation!” in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (1899).

The text reads, “RELATIVE BRUNETNESS BRITISH ISLES, after Beddoe ’85 [Races of Britain] 13,088 observations.” On the right the scale ranks the “INDEX OF NIGRESCENCE,” with light skin and hair at the top and dark skin and hair at the bottom.

This map also attempts to define linguistic groups: a line between highland and lowland Scotland traces the boundary of the Gaelic speech of Scotland and Ireland (“Gaelic Celtic”); another line separates English from the Gaelic of Wales and the Channel Islands (“Kymric Celtic”); a line through Ireland demarcates the eastern borderline of Irish Gaelic. These unreliable linguistic boundaries often reappeared as racial boundaries between Briton and Celt. Lowland Scots such as Thomas Carlyle and Robert Knox, you may recall, were delighted to be British Saxons rather than highland Scottish Celts.

RACES OF EUROPE vaulted to success immediately on publication in 1899. The New York Times devoted two full pages to a glowing review, reproducing several of the book’s photographs. The Times reviewer (identified simply as W.L.) raves about Ripley’s “great work” of “elaborate scope and exhaustive treatment.” Best of all, Ripley demolished the “schoolroom fallacy that there is such a thing as a single European or white race.”14 Addressing general readers, the Times underlines this telling point in an era of alarming European immigration. Scholars also loved Races of Europe. The sheer amount of labor it required delighted the American Anthropologist’s reviewer, who gushed over “the best results of the last twenty years in physical anthropology.”15

Fig. 15.8. “Relative Brunetness British Isles,” in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (1899).

The British edition of 1900 prompted the Royal Anthropological Society to give Ripley anthropology’s crowning honors, the Huxley Medal and an invitation to deliver the Huxley Lecture of 1902. Occupied with a move from part-time appointments at MIT and Columbia to a permanent post at Harvard, Ripley was unable to accept for 1902. Later he remarked with youthful hubris that Sir Francis Galton, the world’s most famous statistician—and the father of eugenics—had substituted for him.16 Ripley did finally deliver the 1908 Huxley Lecture, the first American to achieve this singular mark of distinction. The New York Times reported his lecture under the pithy headline of “Future Americans Will Be Swarthy.”17 Like Races of Europe, Ripley’s Huxley Lecture delivers racist notions in scholarly tones.* He predicts a “complete submergence” of Anglo-Saxon Americans to follow the “forcible dislocation and abnormal intermixture” of many races and the low Anglo-Saxon birthrate. He also frets that Jews (“both Russian and Polish”) were dying at too slow a rate, “only one-half that of the native-born American,” despite living in abysmal circumstances. While Anglo-Saxons avoided having children, short, dark, round-headed Jews in the tenements multiplied alarmingly. Echoing his mentor Francis Amasa Walker’s phrasing, Ripley warns that immigration was now tapping “the political sinks of Europe,” bringing a “great horde of Slavs, Huns and Jews, and drawing large numbers of Greeks, Armenians and Syrians. No people is too mean or lowly to seek an asylum on our shores.”

Reiterating favorite themes in European racial science, Ripley warns that the tendency of city people to be darker “can not but profoundly affect the future complexion of the European and American populations.” Ripley’s surmise that these dark-haired men were more sexually potent than blonds repeats speculations of Emerson and others, adding a note of anxiety. Ending ruefully, Ripley posits that all might not be lost. Even if Anglo-Saxon Americans followed American Indians and the buffalo into extinction, surely their mixture with others would mean a continued, worthy life. After all, there exists a “primary physical brotherhood of all branches of the white race.” The white race?

Dancing about the hot coals of theory in 1908, Ripley says there might be only one white race, not the three of 1899. Even further, perhaps, “all the races of men” belong to the same human brotherhood, and “it is only in their degree of physical and mental evolution that the races of men are different.”18 If so, nevertheless, some races (the white) are more advanced—more “evolved”—than others (the dark).

This cloudy perversion of Darwinian evolution and Mendelian inheritance thrived in the early twentieth century. Like most of his scholarly peers, Ripley believed that races of people, like Gregor Mendel’s garden peas, inherited gross “unit” traits, such as intelligence, head shape, pigmentation, and height. Because Ripley believed that the original Europeans—those primitive, Stone Age Celts fated for displacement—were dark, he concludes that the “abnormal intermixture” of peoples in the United States would lead to a “reversion to the original stock.” The hybrids might be even darker than the dark parent because of “the greater divergence” of stocks. If Italian men mated with Irish women, they would produce “the more powerful…the reversionary tendency” toward darkness. There could be no intermediate pigmentation.

Harvard’s prestige played a large part in the longevity of such nonsense as scientific truth. But mostly The Races of Europe spoke to a race-obsessed nation by delivering the right opinions dressed up as science. Never mind that the book could not survive a careful reading, that it bulged with internal contradiction, or that its tables and maps offered a Babel of conflicting taxonomies. William Z. Ripley’s Races of Europe remained definitive for the next quarter century.

ALTHOUGH Races of Europe defined Ripley’s reputation over the long run, it represented a detour in his scholarship, for the young Ripley had first been a promising economist rather than an anthropologist. True, Races of Europe brought him excellent job offers from Cornell, Columbia, Yale, and Harvard. But the position he accepted in 1902 took him into Harvard’s Department of Political Economy, where he remained until his retirement in 1933, when, like his mentor Francis Amasa Walker, he served as president of the American Economic Association.19

In these many years Ripley’s reputation shone brightly. He appeared regularly in the New York Times. In the mid-1920s he warned President Calvin Coolidge, investors, and politicians of the dangers of unsound railroad financing and appeared as a cartoon character measuring railroad financial soundness. (See figure 15.9, Ripley measuring the railroads.) During the Hoover years of the Great Depression, he advocated government regulation along lines that would become President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. In fact, Ripley had taught Roosevelt at Harvard, delivering lectures that apparently inspired the reform of the American economy.20

Through it all the New York Times covered him diligently, printing his warnings and reviewing his books. It reported Ripley’s auto accident, his nervous breakdowns, his retirement, his death, and, a quarter of a century later, the death of his wife.21 All this attention signified a scholar at the top of the heap. But an immigrant of an original turn of mind was rising to challenge his preeminence.

Fig. 15.9. The New York Times shows Ripley measuring the railroads.