17

ROOSEVELT, ROSS, AND RACE SUICIDE

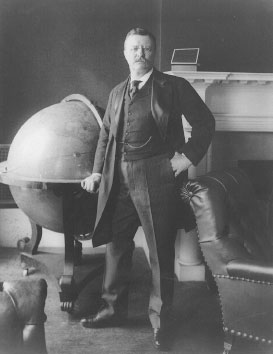

Well-born, impeccably educated, and a master communicator, Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) never lost sight of race as the driving force of human history, especially of his “American race.” (See figure 17.1, Theodore Roosevelt.) In books and articles throughout his public life, Roosevelt could alter his emphases depending on the political context, but he was always a leading race thinker of his times.* And he got started early.

As a youngster, Roosevelt admired the heroics depicted in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Saga of King Olaf” in Tales of a Wayside Inn (1863). During a summer in Dresden, Germany, when he was fourteen, Roosevelt was exposed to the Nibelungenlied (that pagan German saga of Siegfried the dragon slayer), deepening his sense of Teutonic heritage.1 Later, as an undergraduate at Harvard, he absorbed the ideas of American racial greatness and immigrant inferiority from Professor Nathaniel Southgate Shaler of Kentucky and came to agree with Shaler on a popular tenet of American race talk. Like so many other old-line Americans, Roosevelt easily saw the figure of this tall, slender Kentuckian as the quintessential native American. And in graduate studies at Columbia, Roosevelt also absorbed the Teutonist notions of John W. Burgess, another conservative admirer of all things German.

Fig. 17.1. Theodore Roosevelt as Master of the World.

Roosevelt’s rise in politics proved vertiginous. A Republican by birth, he was appointed assistant secretary of the navy in 1898, at age thirty, a stint followed by volunteer service in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. His well-publicized war record helped him get elected governor of New York and, in 1900, placed as vice president on a Republican ticket headed by William McKinley. Roosevelt was forty-two years old when he became president after McKinley’s assassination in 1901. Serving as a progressive, even a trust-busting president between 1901 and 1909, he returned to politics as the presidential nominee of the Progressive Party in the 1912 campaign that brought the Democrat Woodrow Wilson to the White House.

During this entire time Roosevelt spoke and wrote tirelessly, starting off with a series of Teutonist histories and biographies: The Naval War of 1812 (1882), Thomas Hart Benton (1887), Gouverneur Morris (1888), and The Winning of the West (1889–96).2 The American Historical Association (AHA) acknowledged his contribution to the writing of history by electing him president in 1912. This selection was unsurprising, since Roosevelt had succeeded wildly as a historian. Moreover, as a strident Teutonist, he fit in well with his AHA predecessors: the Boston Brahmin-statesman-historian George Bancroft in 1886, the industrialist turned award-winning historian James Ford Rhodes in 1899, the Boston Brahmin grandson and great-grandson of presidents Charles Francis Adams in 1901, the Anglo-Saxonist, imperialist historian Alfred Thayer Mahan in 1902, and Roosevelt’s Harvard classmate and friend the Harvard history professor Albert Bushnell Hart in 1909.*

Echoing Carlyle’s Norse theme in the 1880s, Roosevelt’s Thomas Hart Benton hails the “most war-like race” those hardy frontiersmen, conquerors of the West like “so many Norse Vikings.” Echoing Emerson in English Traits, Roosevelt practically savors the “hideous brutality” of warfare against the Indians. Indeed, Roosevelt’s enthusiasm for virile violence knows few bounds. Intrepid Americans who take over Texas merge into Emersonian Norsemen as “Norse sea-rovers,” “a ship-load of Knut’s followers,” and “Rolf’s Norsemen on the seacoast of France.” Roosevelt pictures Sam Houston as an “old world Viking” whose life as a whole emerges “as picturesque and romantic as that of Harold Hardraada himself.”3†

Thus, early on, Roosevelt bought into much of the Teutonic hypothesis of American governmental institutions, but not quite all of it. Others, such as the Reverend Josiah Strong, were jubilantly predicting the universal reign of the Anglo-Saxon at the expense of all other races. Strong’s book Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis (1886) primed Americans for a final conflict between Anglo-Saxons and others, with, presumably, Irish and other Celts on the losing side.4 It sold 175,000 copies in a generation.

Not quite so narrow, Roosevelt acknowledged the mixed racial nature of Britons and Americans—race, of course, meaning the European races alone. In what today seem like trivial nuances, Roosevelt usually termed his superior race “English-speaking,” rather than simply “English.” Nonetheless, his reasoning made “native Americans”—that is, Anglo-Saxon Protestants—uniquely suited racially for self-government, thanks to their Teutonic heritage. Everybody who was anybody could agree on that. Of course, as with all race talk, conflicting assumptions and disparate conclusions arose. A century ago they could draw blood.

Controversy reigned over whether Americans or Englishmen or even Germans had inherited the self-governing genius of medieval German forests. The English Anglo-Saxonist E. A. Freeman chose his own England, but accepted Americans into his race club. Herbert Baxter Adams, holder of a Ph.D. from Heidelberg (most American race theorists studied in Germany at one time or another), taught at Johns Hopkins. A prideful New Englander, he planted medieval Germans’ descendants in New England, rather bypassing England itself. The Harvard Ph.D. and young congressman Henry Cabot Lodge, a New Englander of self-proclaimed Norman French heritage, saw much virtue in the Norman contribution to England, yet spoke often and easily of “the English race.” Following Carlyle, Lodge saw Normans as Saxons who happened to speak French and therefore as full-blooded Teutons. John W. Burgess, a political scientist at Columbia University, had spent 1870–73 studying at Göttingen. Burgess held that Germans monopolized racial and political superiority, even down to his own times.

More than a little distrust crept into race theory with regard to present-day Germans. As imperial rivalries raged in early twentieth-century Europe, Burgess pushed for a political alliance of the “Teutonic” powers of Germany, England, and the United States against France. But Lodge distrusted both Britain and Germany. Roosevelt, meanwhile, shied away from Germany, calling it the land of “swinish German king-lets who let out their subjects to do hired murder, and battened on the blood and sweat of the wretched beings under them.”5 The lawyer, philosopher, and social Darwinist historian John Fiske, the leading American popularizer of Anglo-Saxonism, held, “We New Englanders are the offsprings of Alfred’s England,” but nonetheless, “we—the English—are at least three-quarters Celtic…. I believe that in blood, we are quite as near to the French as to the German—probably more so.” Most other turn-of-the-century Teutonists (like Emerson earlier) thought the French stood for all that was alien to the democratic, but not revolutionary, Anglo-Saxon genius. Even Henry Cabot Lodge, the self-proclaimed Cabot descendant, made his French ancestors into Saxons, the better to admire the Germans of Tacitus and Caesar.6 And so it went. Tempests we now set in a teapot, but at the time a big, important pot of tea.

Like the majority of his contemporaries, Roosevelt made race (not, say, class) the major force of human history, but his notion of American race changed over time. In his early work, Americans and Englishmen are much the same race, a product of German, Irish, and Norse combining in the British Isles. In admitting the Irish admixture, Roosevelt parted ways with some of his fellow Teutonists. His teacher Burgess, for instance, had locked the Irish out of the Teutonic race, and Roosevelt’s friend Henry Cabot Lodge initially had hard words for the Irish. Politics, where the Irish represented a potent force, made all the difference. After Lodge entered politics, he like Roosevelt came around as his Irish American constituents forced him to soften this critique.

Darwinian evolution proved more problematic. A progressive thinker, Roosevelt accepted the validity of evolution but gave it his own, racial spin. As he pondered the great sweep of English and American history, he agreed with other modern scientific thinkers, including Ripley, that Darwin had to be right. But any evolutionary change would occur only very, very, very slowly and, crucially, in terms of what we now more easily see as culture: a race must surely require a thousand years or more to develop temperamentally to the level of Teutons. But once thus formed, fine traits would be passed along within the race. Thus, Americans of Teutonic descent possessed “that union of strong, virile qualities…that inestimable quality, so characteristic of their race, hard-headed common sense.” Perhaps other races, even southern Italians, would evolve in their turn, but evolution to a superior level could not take place anytime soon. Woodrow Wilson, the Princeton political scientist and future president, agreed. The superior “English race” had risen through “slow circumstance.”7* So must all the others, by patiently waiting their turn.

According to this psycho-cultural notion of evolution, temperament trumped all, but the right temperament was under siege, as the census of 1890 made clear. The wrong people were increasing, and the right people were not.

Roosevelt first glimpsed danger in the early 1890s, as did Francis Amasa Walker, in the declining birthrate among old-stock New Englanders. French Canadians migrating to jobs in the American textile industry struck Roosevelt as a dangerous mass “swarming into New England with ominous rapidity.” By 1895 what Roosevelt called the “warfare of the cradle” had intensified. It was becoming ever more difficult to “prevent the higher races from losing their nobler traits and from being overwhelmed by the lower races.”8

“RACE SUICIDE” loomed as an issue “fundamentally infinitely more important than any other question in this country.”9 For Roosevelt, this was not a matter of workers versus capital or the poor versus the rich. It was a kind of race war pitting the higher races of his native Americans against two groups deemed inferior by dint of their heredity: “degenerate” poor white families of native descent and immigrant workers from southern and eastern Europe. (African Americans hardly figured in this discussion, as prominent race thinkers had convinced themselves that the Negro was dying out, unfitted as he was to live outside of slavery.) As a race publicist in the era of rising worker unrest, Roosevelt dedicated the last decades of his life to exhorting the better classes to reproduce more lustily in order to meet and, he hoped, overcome the demographic competition of their inferiors.

Great slogans are rare, and this one—“race suicide”—though co-opted by Theodore Roosevelt, was not of his invention. Rather, it was coined by the popular and distinguished sociologist Edward A. Ross (1866–1951) in 1901. (See figure 17.2, Edward A. Ross.) In “The Causes of Racial Superiority,” both an address to his colleagues in the social sciences and a widely quoted article in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Ross stresses something he terms racial temperament over biological race.10* He puts it all together—the dominance of racial temperament, the minor role of biological race, disastrous demographics—producing the catastrophe of “race suicide” looming on the horizon. His emblematic phrase picks up Francis Amasa Walker’s unfavorable demographics and echoes Walker’s wording.

Well before his sloganeering, Ross had scaled the heights of American academia. Receiving his B.S. from Coe College in 1886, he went on to study at the University of Berlin and Johns Hopkins Universities (Ph.D. 1891), then moved around quite a bit. After posts at the Universities of Indiana, Cornell, Stanford, and Nebraska, he capped off a fine career at the University of Wisconsin, the leading American institution in social science.† A founder of sociology in U.S. universities, Ross was elected president of the American Sociological Association in 1914 and 1915. He also excelled as a popularizer of social scientific truth; his books sold half a million copies during his lifetime.11

Fig. 17.2. Edward A. Ross.

Like other declarations on race, “The Causes of Racial Superiority” contradicts itself from one statement to the next. Ross opens by denigrating the old-fashioned concept of race as “the watchword of the vulgar.” What the craniometricians measure—head shape as a racial trait—interested him not at all. Ross’s racial characteristics are temperamental: “climatic adaptability,” “energy,” “self-reliance,” “foresight,” “stability of character,” and “pride of blood.”12 These were the concepts to focus on.

In page after page, Ross beats his drum: “the Celtic and Mediterranean races,” “domesticated races” and “economic races,” “the higher races,” “the great races,” “the higher blood,” “the Superior Race” with capital letters, and, echoing Emerson’s “singing and dancing nations,” “the childishness or frivolousness of the cheaply-gotten-up, mañana races.” “The economic virtues,” he concludes in italics, “are a function of race.”13* All this appears in a lecture aimed at an audience of scholars of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

Writing for a popular audience in the Independent, Ross echoes Emerson’s and Roosevelt’s image of American pioneers as Vikings, selected “not for the brainiest or noblest or highest bred” but for the “strongest and most energetic.”14 Like Ripley and the Teutonists, Ross prizes height and denigrates by name the people he thinks too short. Sardinians did not make the cut, nor did those “masses of fecund but beaten humanity from the hovels of far Lombardy and Galicia,” and “cheap stucco manikins from Southeastern Europe…from Croatia and Dalmatia and Sicily and Armenia, they throng to us, the beaten members of beaten breeds…Slovaks and Syrians…as undersized in spirit, no doubt, as they are in body.”15

Finally, willing to use any weapon at hand, Ross accepts the reasoning of then fashionable, self-styled European “anthroposociologists,” physical anthropologists Otto Ammon and Georges Vacher de Lapouge, who bent Darwinian natural selection to their mania of craniometry and had also made their way into William Z. Ripley’s influential Races of Europe. Ammon and Lapouge were spinning out fantastical theories of race temperament based on the cephalic index, famously pronouncing European townspeople more long-headed (meaning, for them, more Teutonic and superior) than the people of the surrounding countryside (those more Celto-Slav and inferior). Following them, Ross concludes that the “city is a magnet for the more venturesome, and it draws to it more of the long-skulled race than of the broad-skulled race…. [T]he Teuton’s superior migrancy takes him to the foci of prosperity, and procures him a higher reward and a higher social status.” For someone dismissing race as superstition, Ross bought right into the mumbo jumbo of racial skull shapes.16*

In lockstep with Ross, Roosevelt opined, “If all our nice friends in Beacon Street, and Newport, and Fifth Avenue, and Philadelphia, have one child, or no child at all, while all the Finnegans, Hooligans, Antonios, Mandelbaums and Rabinskis have eight, or nine, or ten—it’s simply a question of the multiplication table. How are you going to get away from it?”17 But Roosevelt did not have the public sphere to himself. While he was nagging educated women of “our own type” to bear babies, a less articulate, but nonetheless oppositional, discourse arose that undercut his fundamental assumptions. Worker-oriented commentary, especially (but not exclusively) in the foreign-language press, disputed both the notion of upper-class racial superiority and the logic of racial determinism. Their point was well taken, for the so-called beaten men from beaten races were doing most of the work. In the garment, iron, and steel industries, in the mines and mills that kept the amazing American economy running, immigrants supplied the necessary brawn. The rhetoric flowing from the country’s Roosevelts and the Rosses might harp on race—the Italian race, the Jewish or Hebrew race, the Anglo-Saxon race. Such blather only obscured—in words, at least—the gaping chasm between the classes, and the working classes were beginning to have their say.

THE INDUSTRIAL Workers of the World (IWW, or Wobblies), founded in 1905, became the most visible sign of working-class mobilization. Repudiating the American Federation of Labor’s business model of organizing only skilled workers (now monopolized by English-speaking northwestern Europeans, especially Irish Americans), the IWW welcomed all kinds with an “industrial” model that sought to bring the unskilled, immigrant masses into unions by stressing their interests as workers.18*

With their working-class readership, Italian and Yiddish newspapers came to reflect the anarchist and socialist views of their readers. The earliest Italian and Yiddish newspapers sprang up in New York in the 1880s, with the left press appearing in the following decade. The anarchist Il Proletario was founded in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1902, as the organ of the Italian Socialist Federation, joining the socialist Jewish Daily Forward founded in 1897. Such papers depicted American society quite differently from the tony journals that couched their race theory in quasi-scientific, quasi-historical terms.

Italian anarchists especially heaped scorn on American self-righteous blindness, above all when it came to injustices inflicted on blacks in the South. True, other immigrant workers had become targets of labor abuse, but Italians had suffered a special wound, the lynching of eleven Italians in New Orleans in 1891. As though to echo David Walker’s 1835 accusations, Il Proletario skipped over the idea of white races and stressed the injustices of black Americans at the hands of native-born whites. A blast from Il Proletario in 1909 asked,

Who do they think they are as a race, these arrogant whites? From where do they think they come? The blacks are at least a race, but the whites…how many of them are bastards? How much mixing is their “pure” blood? And how many kisses have their women asked for from the strong and virile black servants? As have they, the white males, desired to enjoy the warm pleasures of the black women of the sensual lips and sinuous bodily movements? But the white knights care little for the honor and decency of the black women, whom they use and abuse as they please. For these, race hatred is a national duty.

Sounding a note that grew louder and louder, Il Proletario reached a ringing conclusion: “Not race struggle but class struggle.”19

BUT IT was too early, and Il Proletario’s exhortation fell on ears attuned to another sort of analysis, one that interpreted class status as permanent racial difference with African Americans largely cornered in the South; the “race” in this race question was as much white as black.